Bupropion, AHFS

Diunggah oleh

Annisa Nur JDeskripsi Asli:

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Bupropion, AHFS

Diunggah oleh

Annisa Nur JHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

28:16.04.

92 Miscellaneous Antidepressants

Bupropion Hydrochloride

Introduction

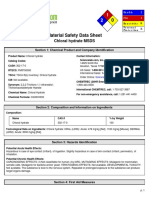

C13H18ClNOClH

Bupropion hydrochloride is an aminoketone-derivative antidepressant agent1, 43, 142 that is chemically unrelated to tricyclic, tetracyclic, or other currently available antidepressants (e.g., selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors)1, 43, 142, 143 and also is chemically unrelated to nicotine or other agents currently used in the treatment of nicotine dependence.

Uses

Major Depressive Disorder Bupropion hydrochloride is used in the treatment of major depressive disorder.1, 127, 128, 129, 131, 132, 142 The manufacturer states that efficacy of conventional bupropion tablets for long-term use (i.e., exceeding 6 weeks) as an antidepressant has not been established by controlled studies; if the drug is used for extended periods, the need for continued therapy should be reassessed periodically.1, 142 Systematic evaluation of bupropion hydrochloride extended-release tablets has shown that antidepressant efficacy is maintained for periods of up to 44 weeks in patients receiving 150 mg twice daily.142

Efficacy of bupropion for the management of major depression has been established by a controlled study of approximately 6 weeks' duration in an outpatient setting and by 2 controlled studies of approximately 4 weeks' duration in inpatient settings.1, 3, 142 Bupropion hydrochloride was

administered as conventional tablets in these studies,142 and the dosage received by 78% of the patients in one of the studies of 4 week's duration was 450 mg or less daily, although the dosage was titratable to 600 mg daily.142 Efficacy of bupropion in these studies was demonstrated by improvement in total score on the Hamilton rating scale for depression (HAM-D), in item 1 of the HAM-D that measures depressed mood, and in the Clinical Global Impressions of Severity of Illness (CGI-S) scale.142 Patients received 300 or 450 mg daily of bupropion hydrochloride in the second study of 4 weeks' duration, which demonstrated efficacy only of the higher dosage, as indicated by improvement in total score on the HAM-D and in the CGI-S scale.142 However, in the study of 6 weeks' duration that evaluated the efficacy of 300 mg daily of bupropion hydrochloride, the drug was superior to placebo in improvement of total score on the HAM-D, which was the primary measure of efficacy.3, 142 In addition, depressed mood, as measured by item 1 on the HAM-D, was improved in patients treated with bupropion.142 The drug also was superior to placebo in improvement of scores on the MontgomeryAsberg Depression Rating Scale, the CGI-S scale, and the Clinical Global Impressions of Improvement (CGI-I) scale.3, 142 Although clinical studies specifically establishing the efficacy of extended-release tablets of bupropion in the management of major depression have not been performed to date, this formulation of the drug has been shown to be bioequivalent at steady state to conventional tablets of bupropion, and antidepressant efficacy was maintained for up to 44 weeks in a placebo-controlled study.142 (See Pharmacokinetics: Absorption)

A major depressive episode is characterized principally by a relatively persistent depressed mood and/or loss of interest or pleasure in all or almost all activities;1, 107, 142 such symptoms differ from previous functioning and occur for most of the day nearly every day for at least 2 weeks.1, 107 In addition, the episode may be manifested as a change in appetite, substantial weight loss or gain, a change in sleep, psychomotor agitation or retardation, fatigue or loss of energy, feelings of guilt or worthlessness, difficulty in thinking or concentrating, and/or suicidal ideation or attempts.1, 107, 142

Clinical studies have shown that the antidepressant effect of usual dosages of bupropion in patients with moderate to severe depression is greater than that of placebo and comparable to that of usual dosages of tricyclic antidepressants, fluoxetine, or trazodone.2, 3, 44, 45, 53, 54, 92, 93 Bupropion generally was not distinguishable from these antidepressant agents in measures of efficacy that included the Hamilton rating scale for depression (HAM-D), the Clinical Global Impressions of Severity of Illness (CGI-S) scale, the Clinical Global Impressions of Improvement (CGI-I) scale, and the Hamilton rating scale for anxiety (HAM-A).2, 45, 53, 54, 92, 93, 142 However, other antidepressants were associated with greater improvement on the HAM-D rating scale during some weeks of the evaluations principally because of the greater improvement in the sleep factor of this scale observed with tricyclic antidepressants or trazodone in comparison to bupropion.53, 92, 93

Because of differences in the adverse effect profile between bupropion and tricyclic antidepressants, particularly less frequent anticholinergic effects, cardiovascular effects, antihistaminic effects, and weight gain with bupropion therapy, bupropion may be preferred for patients in whom such effects are not tolerated or are of potential concern.2, 23, 44, 104, 127, 128, 133 In a study that compared bupropion with doxepin, discontinuance of therapy because of adverse effects resulted mainly from anticholinergic effects, particularly drowsiness, in patients treated with doxepin but from a variety of adverse effects in patients treated with bupropion.53, 104 After 13 weeks of therapy, patients who received doxepin had gained 2.73 kg while those who received bupropion had lost 1.36 kg.53 Orthostatic hypotension that required discontinuance of the antidepressant agent occurred with some frequency with imipramine but not with bupropion.33, 104 In addition, in a large open study, 54% of patients who responded poorly to previous antidepressant therapy responded to bupropion therapy, and 63% of patients who poorly tolerated previous antidepressant therapy tolerated bupropion; 81% of patients who completed an initial 8-week treatment phase in this study elected to receive maintenance therapy with bupropion.23, 44 Although the possibility of bupropion-induced seizures should be considered in weighing the benefits versus risks compared with alternative therapies,1 the risk of seizures appears to be within clinically acceptable parameters in patients without preexisting risk.23, 24, 44, 141 (See Cautions: Nervous System Effects.)

Bupropion also may be preferable because of its minimal adverse effects on sexual functioning.1, 2, 44, 104, 112, 118 Most men with depression who had sexual dysfunction (e.g., decreased libido, partial erectile failure) with another antidepressant (e.g., tricyclic antidepressant, maprotiline, trazodone, tranylcypromine) did not have such impairment with bupropion.2, 44, 104, 112, 134 Dysfunctional orgasm resolved when antidepressant therapy was changed from fluoxetine to bupropion in most men and women who developed orgasm failure and/or delay with fluoxetine.2, 118 Libido and satisfaction with overall sexual functioning also were improved with bupropion.104, 118 Limited experience suggests that bupropion also may be useful in the management of sexual dysfunction associated with fluoxetine.125 Sexual dysfunction (e.g., decreased libido, erectile and orgasmic impairment) associated with fluoxetine was reported to respond to concomitant administration of 75 mg daily of bupropion hydrochloride.2, 125

For further information on treatment of major depressive disorder and considerations in choosing the most appropriate antidepressant for a particular patient, including considerations related to patient tolerance, patient age, and cardiovascular, sedative, and suicidal risks, see Considerations in Choosing Antidepressants under Uses: Major Depressive Disorder, in the Tricyclic Antidepressants General Statement 28:16.04.24.

Smoking Cessation Bupropion, as extended-release tablets, is used as an adjunct in the cessation of smoking.143, 145, 146, 147, 152 Such therapy may be combined with nicotine replacement therapy if necessary.143, 152 However, the manufacturer states that before patients receive this combination of therapies, the labeling for both bupropion and nicotine should be consulted and recommends that patients who receive bupropion and nicotine concurrently be monitored for the development of hypertension related to such therapy.143(See Cautions: Cardiovascular Effects)

Guidelines Nicotine (tobacco) dependence is a chronic relapsing disorder that requires ongoing assessment and often repeated intervention.152 Because effective nicotine dependence therapies are available, every patient should be offered effective treatment, and those who are unwilling to attempt cessation should be provided at least brief interventions designed to increase their motivation to stop tobacco use.152 Delineated in the current US Public Health Service (USPHS) guideline for the treatment of tobacco use and dependence are 5 brief strategies of intervention that can be provided by any clinician but that are most relevant to primary care clinicians providing service to a wide variety of patients under the constraint of limited time.152 These strategies consist of asking patients if they use tobacco, advising those who use tobacco to quit, assessing their willingness to attempt to quit, assisting those who attempt to quit, and arranging follow-up to prevent relapse.152 Included in the USPHS guideline are recommendations for the use of pharmacotherapy in general, first-line drugs (i.e., extended-release bupropion, nicotine polacrilex gum, transdermal nicotine, nicotine nasal spray, nicotine oral inhaler) that should be considered initially as part of treatment for dependence on tobacco, unless contraindicated, and second-line drugs (i.e., clonidine, nortriptyline).152

Clinicians should encourage all patients attempting to quit smoking to use effective pharmacotherapy, except in the presence of special circumstances (e.g., medical contraindications, less than 10 cigarettes smoked daily, pregnancy, breast-feeding, adolescence).152 When pregnant women are not otherwise able to quit smoking and when the likelihood of cessation, with its potential benefits, outweighs the risks of the pharmacotherapy and possible continued smoking, clinicians should consider pharmacotherapy.152 For the treatment of adolescents, bupropion (exetnded-release) or nicotine replacement therapy may be considered when there is evidence of dependence on nicotine and a desire to quit the use of tobacco.152 For patients receiving treatment for chemical dependence and attempting to quit smoking, clinicians should provide effective treatments for the cessation of smoking that include both counseling and pharmacotherapy, since interventions for the cessation of smoking do not appear to interfere with recovery from chemical dependence.152 Clinicians can consider long-term pharmacotherapy for the cessation of smoking in certain patients, as a strategy to reduce the likelihood of relapse.152

Abstinence should be ascertained at the completion of treatment and subsequently during clinical visits of all patients who receive an intervention against tobacco dependence.152 Treatment to prevent relapse should be provided to abstinent patients.152 In response to relapse, patients should be assessed to determine their willingness at another attempt to quit the use of tobacco.152 Additional treatment should be provided to or arranged for patients willing to attempt again to quit.152 For patients unwilling to attempt again to quit, an intervention to promote motivation to quit should be given by the clinician.152

Because chronic relapses are inherent to dependence on tobacco, the clinician should provide brief treatment to prevent relapse in patients who quit the use of tobacco recently, particularly during the 3 months after they quit.152 Relapse prevention interventions more intensive than minimal practice interventions may be given by the clinician during dedicated follow-up contact held in person or over the telephone, or through a specialized clinic or program.152

Bupropion (extended-release) may be particularly useful in patients greatly concerned about gaining weight after cessation of smoking since therapy with the drug has been shown to result in delay in such gain in weight.152 Nicotine dependence therapy with an antidepressant such as bupropion also may be particularly useful when a depressive disorder is included in the current or past history of patients attempting to quit smoking. 152 Although it is not necessary to assess for possible comorbid psychiatric disorders prior to initiating therapy for nicotine dependence, such comorbidity is important in the assessment and treatment of nicotine-dependent patients since psychiatric disorders are common in this population, smoking cessation or nicotine withdrawal may exacerbate the comorbid condition, and patients with psychiatric comorbidities have an increased risk for relapse to smoking after a cessation attempt.152 However, even though some smokers may experience exacerbation of a comorbid condition with smoking cessation, most evidence suggests that abstinence entails little adverse impact.152 In addition, while psychiatric comorbidity places smokers at increased relapse risk, smoking cessation therapy still can be beneficial.152

Patients should begin receiving bupropion while they are still smoking since steady-state plasma concentrations of the drug are not achieved until after about 1 week.143, 145 A date on which patients quit smoking (cessation date) should be scheduled within the first 2 weeks of therapy with bupropion and generally should be set for the second week (e.g., day 8).143, 145, 152 Counseling and support are important interventions for patients to receive throughout therapy with bupropion and for a period after its discontinuance.143, 145, 152 Achievement of cessation of smoking and maintenance of abstinence are more likely with frequent follow-ups and the provision of support by the clinician and other health-care professionals.143, 145, 146, 147, 152 The importance of participation in behavioral

therapies, counseling, and/or support services to which bupropion is adjunctive therapy should be discussed with the patient.143, 147 The overall program of interventions to enable cessation of smoking should be reviewed by clinicians.143, 146, 147 The choice of adjunctive therapy (e.g., nicotine replacement, bupropion) should consider factors such as ease of administration, compliance, and potential adverse effects and risks.146

For additional information on smoking cessation, see Guidelines under Uses: Smoking Cessation, in Nicotine 12:92.)

Clinical Studies The efficacy of bupropion, as extended-release tablets, as an adjunct in the cessation of smoking has been established in controlled studies of smokers of at least 15 cigarettes daily, who did not have an underlying depressive disorder.143, 145, 146 Patients were treated with bupropion in conjunction with individual counseling.143, 145 Cessation of smoking was defined as total abstinence, as determined with patients' daily diaries and verified by measurement of expiratory carbon monoxide, during the fourth through seventh week of treatment.143, 145 Treatment over 7 weeks with bupropion or placebo resulted in 1-year cessation of smoking in a greater proportion of patients treated with the drug at a dosage of 150 or 300 mg daily but not in those receiving 100 mg daily.143, 145 Cessation of smoking was achieved at the end of 7 weeks of treatment in 36-44, 27-39, or 17-19% of patients who received 300 mg daily of bupropion hydrochloride, 150 mg daily of the drug, or placebo, respectively.143, 145 Maintenance of abstinence was observed with bupropion hydrochloride at a dosage of 300 mg daily.143 At follow-up during the twelfth week, abstinence continued in 25-30 or 14% of patients who had received bupropion hydrochloride at 300 mg daily or placebo, respectively,143, 145 and at follow-up during the twenty-sixth week, abstinence continued in 19-27 or 11-16% of patients who had received bupropion hydrochloride at 300 mg daily or placebo, respectively.143

Treatment over 9 weeks with bupropion at a dosage of 300 mg daily, transdermal nicotine at a dosage of 21 mg/24 hours, the combination of 300 mg daily of bupropion and transdermal nicotine at 21 mg/24 hours, or placebo resulted in cessation of smoking in a greater proportion of patients treated with bupropion, transdermal nicotine, or the combination of bupropion and transdermal nicotine than in those receiving placebo.143 Cessation of smoking was achieved during weeks 4-7 in 49, 36, 58, or 23% of patients who received bupropion, transdermal nicotine, the combination of bupropion and transdermal nicotine, or placebo, respectively.143 At follow-up during the tenth week, abstinence was observed in 46, 32, 51, or 20% of patients who had received bupropion, transdermal nicotine, the combination of bupropion and transdermal nicotine, or placebo, respectively.143 Additionally, when these patients were assessed at 26 weeks, cessation of smoking continued to be observed in 30, 33, and 13% of patients who received bupropion, the combination of bupropion and transdermal nicotine, or

placebo, respectively.143 A final assessment was performed at 52 weeks and abstinence continued to be observed in 23, 28, and 8% of patients who received bupropion, the combination of bupropion and nicotine, or placebo, respectively.143 The manufacturer states that because the comparisons between bupropion extended-release tablets, transdermal nicotine, or the combination of these products have not been replicated, these data should not be interpreted as demonstrating superiority of any individual treatment protocol.143

Another clinical study also reviewed long-term maintenance treatment with bupropion.143 Patients received bupropion hydrochloride extended-release tablets at a dosage of 300 mg daily for 7 weeks; therapy was continued in the patients who achieved cessation of smoking at 7 weeks with either bupropion hydrochloride extended-release tablets or placebo.143 At 6-month follow-up, abstinence continued in 55% of patients receiving bupropion compared with 44% of patients who received placebo therapy.143

The safety and efficacy of bupropion extended-release tablets as an adjunct in the cessation of smoking in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) was established in a clinical trial in adults with mild to moderate COPD (FEV1 at least 35%, FEV1/FVC 70% or less, and a diagnosis of chronic bronchitis, emphysema, and/or small airways disease).143 Treatment over a 12 week period with bupropion or placebo resulted in cessation of smoking during the final four weeks of the study in 22 or 12% of patients, respectively.143

Since efficacy in clinical studies is influenced by the population selected, a lower rate of cessation of smoking is possible with use of bupropion in an unselected population.143 The reported cessation rates in patients receiving bupropion were similar in patients who had and had not previously received nicotine replacement therapy for the cessation of smoking.143 Withdrawal symptoms, especially irritability, frustration, anger, anxiety, difficulty concentrating, restlessness, and depressed mood or negative affect, were reduced with bupropion compared with placebo.143, 145 Craving for cigarettes or urge to smoke appeared to be reduced with bupropion in comparison with placebo.143

Bipolar Disorder Bupropion has been used for the treatment of bipolar depression (bipolar disorder, depressive episode).2, 77, 78, 85, 86, 102 Lithium preferably or lamotrigine alternatively are considered first-line agents by the American Psychiatric Association (APA) for the treatment of acute depressive episode of bipolar disorder, and lamotrigine (if not used initially), bupropion, or paroxetine are considered secondline agents when first-line agents are ineffective or not tolerated.154 If bupropion was effective for the management of an acute depressive episode, including during the continuation phase, then

maintenance therapy with the drug should be considered to prevent recurrences of major depressive episodes.154 In a comparative study, bupropion (mean dosage of 358 mg daily) was as effective as desipramine (mean dosage of 140 mg daily) in the management of depression in patients with bipolar disorder.2, 85 Hypomania or mania occurred less frequently with bupropion than with desipramine in patients treated for up to 1 year with either drug and concomitant lithium, carbamazepine, or valproate sodium.85

Because bupropion may be less likely than some other antidepressants to cause a switch to mania or rapid cycling in patients with bipolar disorder, many experts consider bupropion a preferred antidepressant for use in combination with a mood-stabilizing agent in patients with severe (nonpsychotic) depression that is unresponsive to therapy with mood-stabilizing agents alone.154, 155 However, the possibility that manic attacks may be precipitated in patients with bipolar disorder who receive bupropion still must be considered.1, 13, 14, 44, 86, 89 To reduce the risk of developing mania, antidepressants should not be used alone in patients with depression associated with bipolar disorder and the lowest effective dosage of the antidepressant should be used for the shortest time necessary. 154, 155

For further information on the management of bipolar disorder, see Uses: Bipolar Disorder, in Lithium Salts 28:28.

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder Bupropion has been used in a limited number of children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).2, 44, 79, 80, 134, 156, 157, 158 Although stimulants (e.g., methylphenidate, dextroamphetamine) usually are considered the drugs of first choice when pharmacotherapy is indicated as an adjunct to psychological, educational, social, and other remedial measures in the treatment of ADHD in children,156, 157 some clinicians recommend use of bupropion or tricyclic antidepressants as second-line therapy when there has been no response to at least 2 stimulants or when the patient is intolerant of stimulants.156, 158 In controlled studies, bupropion was more effective than placebo2 and comparably effective to methylphenidate.2, 79 In addition, in a comparative study, bupropion hydrochloride (mean dosage of 3.3 mg/kg daily; range: 1.4-5.7 mg/kg daily) was comparably effective to methylphenidate hydrochloride (mean dosage of 31 mg daily; range: 20-60 mg daily) in overall improvement of symptoms, as evaluated with the Iowa-Conners Abbreviated Parent and Teacher Questionnaire, although a trend favoring methylphenidate was noted in almost all rating scales.2, 79

Bupropion also has been used in a limited number of adults with ADHD.2, 44, 76, 126 In an uncontrolled study in adults, bupropion (mean dosage of 359 mg daily; range: 150-450 mg daily) administered for 6-8 weeks reduced the severity of signs and symptoms of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, as evaluated with the Targeted Attention Deficit Disorder Symptoms Scale.2, 76 Additional study and experience are needed to establish the role of antidepressants versus CNS stimulants in the treatment of this disorder.2, 44, 76, 126

For further information on management of ADHD, see Uses: Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder in Methylphenidate 28:20.

Other Uses Bupropion does not appear to be effective in the treatment of panic disorder and concomitant phobic disorder.2, 44, 99, 134 However, the drug generally improves symptoms of panic and depression in patients with major depression who have superimposed panic symptoms.44

Although bupropion has been used effectively in some patients with bulimia nervosa, the American Psychiatric Association (APA) states that the drug has been associated with seizures in purging bulimic patients and cautions against its use in the management of this disorder.153 For information on the use of antidepressants in the treatment of bulimia nervosa and other eating disorders, see Uses: Eating Disorders, in Fluoxetine 28:16.04.20.

Dosage and Administration

Administration Bupropion hydrochloride is administered orally.1 As conventional tablets, the drug usually is administered 3 times daily, preferably with 6 or more hours separating doses, or in the morning, at midday, and in the evening.1, 23, 24, 141

Bupropion hydrochloride extended-release tablets should be swallowed whole so that the slow drugrelease characteristics are maintained.142 Patients should be instructed not to chew, divide, or crush the extended-release tablets.142, 143 As extended-release tablets, bupropion hydrochloride usually is administered twice daily in the morning and evening.142 For patients who develop marked insomnia

while receiving extended-release bupropion, taking the evening dose earlier (e.g., in the afternoon, but at least 8 hours after the morning dose) may provide some relief.152

Bupropion therapy with conventional tablets usually is initiated with administration twice daily, in the morning and in the evening.1 As extended-release tablets, bupropion hydrochloride therapy usually is initiated with administration of a single daily dose in the morning.142

A retrospective analysis of clinical experience suggests that the risk of seizures during bupropion therapy may be minimized by increasing dosages gradually, by not exceeding the recommended maximum daily dosage (400 mg as extended-release tablets or 450 mg as conventional tablets), and by administering the daily dosage in 2 divided doses with a maximum single dose of 200 mg (as extended-release) or in 3 divided doses with a maximum single dose of 150 mg (as conventional tablets).1, 142 Increasing the dosage gradually also lessens the occurrence of agitation, motor restlessness, and insomnia commonly experienced when bupropion therapy is initiated.1, 142 If any of these adverse effects occur and are troublesome, temporarily reducing dosage or delaying any dosage increases may be useful.1, 142

Avoiding bedtime administration of the evening dose of bupropion may lessen the occurrence of insomnia (commonly experienced during initiation of bupropion therapy).1, 142 Short-term administration of an intermediate- to long-acting sedative hypnotic also may be useful during the first week of therapy but thereafter generally is not needed.1, 8, 142

Dosages exceeding 300 mg daily as conventional tablets are administered as divided doses that should not exceed 150 mg.1 Conventional tablets of 75 or 100 mg can be used to create the divided doses.1 If the components of a larger dosage include 4 whole conventional tablets of 100 mg, the divided doses are administered 4 times daily separated by 4 or more hours so that none of the doses exceed 150 mg.1 Dosages exceeding 150 mg daily as extended-release tablets should be administered as divided doses twice daily, preferably with 8 or more hours separating the doses.142, 143

Dosage Dosage of bupropion hydrochloride is expressed in terms of the salt.1

Major Depressive Disorder

For the management of depressive disorder in adults, the recommended initial dosage of bupropion hydrochloride as conventional tablets is 100 mg twice daily.1 Alternatively, dosage also has been initiated at 75 mg 3 times daily.23, 24, 141 If no clinical improvement is apparent, dosage may be increased to 100 mg 3 times daily as conventional tablets after at least 3 days of therapy with the initial dosage.1, 23, 24, 141 142

Bupropion hydrochloride dosages exceeding 300 mg daily should not be considered until several weeks of therapy at this dosage level have been completed since maximum effects of a given dosage of antidepressant, in general, may not be fully apparent until after 4 or more weeks of therapy.1, 142 Beyond this time, if no clinical improvement is apparent, dosage of the conventional preparation may be increased to a maximum of 450 mg daily as divided doses not exceeding 150 mg each while dosage of the extended-release preparation may be increased to a maximum of 200 mg twice daily.1, 142

Bupropion hydrochloride dosage as conventional tablets should not be increased by more than 100 mg daily every 3 days.1, 23, 24, 141 Such cautious adjustment of dosage is particularly important in lessening the risk of bupropion-induced seizures.1, 23, 24, 141, 142 If clinical improvement is not apparent after an appropriate trial of 450 mg daily as conventional tablets, the drug should be discontinued since further increases may be associated with an unacceptable risk of toxicity.1, 23, 24, 141

Alternatively, if extended-release tablets of the drug are used for the management of depression in adults, the recommended initial dosage of bupropion hydrochloride is 150 mg as a single dose daily.142 If the initial dosage is tolerated adequately, it may be increased to the target of 150 mg twice daily as early as the fourth day of therapy.142 However, the full therapeutic effect of a given dosage may not be apparent for 4 weeks or longer.142 For patients not exhibiting clinical improvement with 300 mg daily, dosage of the extended-release tablets may be increased to 400 mg daily, given as divided doses of 200 mg twice daily.142 Dosages exceeding 400 mg daily as extended-release tablets are not recommended.142

Although the optimum duration of bupropion hydrochloride therapy has not been established, acute depressive episodes are thought to require several months or longer of sustained antidepressant therapy.1, 142 In addition, some clinicians recommend that long-term antidepressant therapy be considered in certain patients at risk for recurrence of depressive episodes (such as those with highly recurrent unipolar depression).160 Whether the dosage of bupropion required to induce remission is identical to the dosage needed to maintain and/or sustain euthymia is unknown.142 Systematic evaluation of bupropion hydrochloride extended-release tablets has shown that antidepressant efficacy

is maintained for periods of up to 44 weeks in patients receiving 150 mg twice daily.142 The manufacturer states that efficacy of bupropion hydrochloride conventional tablets beyond 6 weeks has not been established systematically in controlled studies.1 The usefulness of the drug in patients receiving prolonged therapy with conventional or extended-release tablets should be reevaluated periodically. 1, 142

Smoking Cessation For use in adults as an adjunct in smoking cessation, the initial dosage of bupropion hydrochloride, as extended-release tablets, is 150 mg daily for the first 3 days of therapy.143, 145, 152 The dosage subsequently is increased in most patients to the usual recommended dosage of 150 mg twice daily, which also is the maximum recommended dosage.143, 145 Dosages exceeding 300 mg daily should not be used for smoking cessation because of the risk of seizures.143 Because steady-state plasma concentrations of the drug are not achieved for about 1 week, bupropion therapy for smoking cessation should be initiated 1-2 weeks prior to discontinuance of cigarette smoking.143, 145, 152 Patients should continue to receive bupropion hydrochloride for 7-12 weeks; the need for more prolonged therapy should be individualized depending on benefits and risks to the patient.143, 152 Discontinuance of therapy does not require that the dosage be tapered.143

For some patients, it may be appropriate to continue pharmacotherapy with bupropion for smoking cessation for periods longer than usually recommended since nicotine dependence is a chronic condition.143, 152 Use of bupropion hydrochloride as an adjunct in smoking cessation has been studied systematically as maintenance therapy at 150 mg twice daily for up to 6 months.143, 152 The decision to continue therapy beyond 12 weeks for smoking cessation must be individualized.143, 152 Although weaning should be encouraged for all smoking cessation pharmacotherapies, continued use of such therapy is clearly preferable to a return to smoking with respect to health consequences.152

Patients have received the combination of bupropion, as extended-release tablets, and transdermal nicotine.143 Patients treated with this combination have been started on bupropion hydrochloride at a dosage of 150 mg daily, while they were still smoking.143 After 3 days, the dosage of bupropion hydrochloride was increased to 150 mg twice daily.143 Patients received concomitant transdermal nicotine therapy at a dosage of 21 mg/24 hours after about 1 week of therapy with bupropion, when the date scheduled for patients to stop smoking was reached.143 The dosage of transdermal nicotine was tapered to 14 and 7 mg/24 hours during the eighth and ninth weeks of therapy, respectively.143

Complete smoking abstinence is the goal of therapy with bupropion hydrochloride.143 Cessation of smoking is unlikely in patients who do not show substantial progress toward abstinence after receiving

bupropion hydrochloride for 7 weeks, so such therapy probably should be discontinued at that time in these patients.143 Unsuccessful patients may benefit from interventions to enhance the possibility for success on the next attempt.143 Such patients should be evaluated to determine why failure occurred,143 and another attempt to quit smoking should be encouraged by a more favorable context that includes elimination or reduction of the factors responsible for failure.143

Depression Associated With Bipolar Disorder While comparative efficacy of various dosages in the usual range have not been established in the management of depression associated with bipolar disorder, some experts recommend that dosages of antidepressants, including bupropion, be titrated to levels comparable to those used in the treatment of unipolar depression.155 In clinical studies in patients with depression associated with bipolar disorder, bupropion hydrochloride has been given in a dosage of 75-400 mg daily in conjunction with a moodstabilizing agent (e.g., carbamazepine, lithium, valproate).2 Antidepressants should be used in these patients for the shortest time necessary.152

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder For the treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in adults, bupropion hydrochloride therapy has been initiated with a dosage of 150 mg daily as conventional tablets.2 Dosage was then titrated to a maximum daily dosage of 450 mg as conventional tablets.2

Although safety and efficacy of bupropion hydrochloride in pediatric patients younger than 18 years of age have not been established, if bupropion is used for the treatment of ADHD in children, some experts recommend that those weighing 20 kg or more receive an an initial dosage of 1 mg/kg daily in 2-3 divided doses. 156 This initial dosage should be given for the first 3 days of therapy, then dosage should be titrated up to 3 mg/kg daily in 2-3 divided doses by day 7 and up to 6 mg/kg daily in 2-3 divided doses or 300 mg (whichever is smaller) by the third week of therapy.156 Alternatively, some experts suggest that pediatric patients with ADHD receive bupropion hydrochloride beginning with an initial dosage of 37.5 mg or 50 mg twice daily with dosage titration over 2 weeks up to a maximum dosage of 250 mg daily (300-400 mg daily in adolescents).157 Up to 4 weeks of bupropion therapy may be necessary to attain maximum effects of the drug.156 Pediatric dosage for ADHD generally has ranged from 50-100 mg 3 times daily.158 If extended-release tablets are used for ADHD, the pediatric dosage generally has ranged from 100-150 mg twice daily.158

Dosage in Renal and Hepatic Impairment

The manufacturer states that the need for modification of bupropion dosage in patients with renal impairment has not been fully determined to date, and the drug should be used with caution in such patients.142, 143 Although bupropion is extensively metabolized in the liver to active metabolites, its active metabolites are renally excreted and may accumulate to a greater extent in patients with renal impairment than in those with normal renal function.142, 143 (See Pharmacokinetics.) Therefore, patients with renal impairment should be closely monitored for possible adverse effects (e.g., seizures) that could indicate higher than recommended drug or metabolite concentration and necessitate a reduction in dose and/or frequency of administration of bupropion.142, 143

Because substantial increases in peak plasma bupropion concentrations and accumulation of the drug may occur in patients with severe hepatic cirrhosis, the manufacturer recommends that bupropion be used with extreme caution in these patients and states that dosage of the drug in these patients should not exceed 75 mg once daily as conventional tablets or 100 mg once daily or 150 mg every other day as extended-release tablets. 1, 142, 143 The drug should also be used with caution in patients with hepatic impairment (including mild to moderate hepatic cirrhosis) and a reduction in dose and/or frequency of administration of bupropion should be considered in these patients.1, 142

Cautions

Bupropion generally is well tolerated.1, 3, 6, 7, 19, 23, 44, 47, 50, 131, 134 Common adverse effects of the drug include agitation, dry mouth, insomnia, headache/migraine, nausea/vomiting, constipation, and tremor.1, 3, 6, 7, 19, 44, 47, 50, 134, 152 Discontinuance of bupropion therapy was required in about 10% of patients and healthy individuals who participated in clinical trials with conventional tablets during the drug's initial development, principally secondary to adverse neuropsychiatric (mainly agitation and abnormal mental status), GI (mainly nausea and vomiting), neurologic (mainly seizures, headaches, and sleep disturbances), and dermatologic (mainly rashes) effects in 3, 2.1, 1.7, and 1.4% of patients, respectively.1, 4, 5, 6, 53 However, these adverse effects often occurred at dosages exceeding the daily dosages currently recommended for major depression.1

The incidences of most adverse effects in controlled trials were reported for bupropion hydrochloride dosages ranging from 300-600 mg daily for 3-4 weeks as conventional tablets,1 and often such effects were reported regardless of whether any attempt was made to attribute them to therapy.1 While the manufacturer's labeling includes comparative incidences for patients receiving placebo,1 reporting apparently similar incidences between bupropion and placebo groups for many of the effects,1, 7, 139, 140 no information is provided on whether significant differences in the incidences of adverse effects exist between the groups.1 Because of the nature and conditions of reporting these effects in clinical

trials, the incidences may not predict precisely the likelihood of encountering adverse reactions under usual medical practice where patient characteristics and other factors differ from those prevailing in the trials.1, 139, 140 In one report of several placebo-controlled trials, only dry mouth was found to occur with an incidence significantly greater than that reported for placebo, occurring in 13.1% more of patients receiving bupropion than placebo, and other adverse effects occurring at incidences that exceeded those for placebo by at least 3% included syncope/dizziness, constipation, tremor, nausea/vomiting, blurred vision, excitement/agitation, and increased motor activity.7

In patients receiving bupropion as an adjunct in the cessation of smoking, the most commonly observed adverse effects consistently associated with the drug were dry mouth and insomnia.143 These adverse effects may be related in incidence to dosage so reduction of the dosage may minimize their occurrence;143 however, dosages less than 150 mg daily may not be effective.143, 145 (See Uses: Smoking Cessation.) Although headache was a commonly reported effect, the incidences between placebo and various bupropion dosages were comparable.145 Therapy was discontinued in 8% of patients commonly because of neurologic (mainly tremors) or dermatologic (mainly rashes) effects,143, 145 which resulted in discontinuance in 3.4 or 2.4% of patients, respectively.143 Other common reasons for discontinuing therapy included headache and urticaria.145 In 2 studies of patients receiving bupropion therapy as an adjunct for cessation of smoking, one in patients with mild to moderate chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) for 12 weeks and another that evaluated long-term administration of bupropion therapy (up to 1 year), the incidence and nature of the adverse effects reported were similar to those reported in previous studies.143

Nervous System Effects Seizures One of the potentially most serious adverse effects of bupropion is reduction in the seizure threshold.1, 2, 3, 6, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 41, 42, 44, 52, 104, 108, 131, 141 However, despite the potential seriousness of this effect, seizures remain a relatively uncommon adverse effect of bupropion therapy, particularly when currently recommended dosages for depression are not exceeded and underlying predisposing factors are not present.1, 2, 6, 19, 23, 24, 44, 141

Seizures reportedly occurred in about 1% or more of patients overall receiving bupropion as conventional tablets, many of whom had predisposing factors;1, 6, 19, 20, 24, 52 however, the risk appears to be strongly associated with predisposing factors and with dosage, with seizures occurring in only approximately 0.4% of patients receiving dosages not exceeding 450 mg daily of bupropion as conventional tablets.1, 2, 21, 22, 23, 24, 41, 42, 44, 104, 131, 141, 142 Seizures reportedly occurred in about 0.1% of patients treated with the extended-release tablets of bupropion hydrochloride at dosages

of 100-300 mg daily.142, 143 Whether this lower incidence of seizures is related to administration of the extended-release preparation or to lower dosages is not known, although since most observed seizures reportedly occurred during steady state, a pertinent consideration in the estimation of incidence is that the extended-release and conventional tablets are bioequivalent in terms of both the rate and extent of absorption of drug at steady state.142 The maximum dosage recommended for the extended-release and conventional tablets are close at 400 and 450 mg daily, respectively, and result in the same incidence of seizures, about 0.4%.142

Of approximately 2400 patients who participated in early clinical trials with bupropion as conventional tablets, 25 patients developed seizures.1, 2, 8, 24 The incidence of seizures was 2.8%, 2.3%, or 0.3%, respectively, in patients treated with dosages of 600-900, 600, or 450 mg and lower daily as conventional tablets.1, 2 In a prospective study of the incidence of seizures in approximately 3200 patients treated with dosages up to 450 mg daily of bupropion, the total incidence of seizures was 0.1 or 0.4% for patients treated for 8 weeks or longer with dosages up to 300 mg daily as extended-release tablets or 300-450 mg daily as conventional tablets, respectively, but most patients experiencing seizures had a predisposing factor (e.g., seizure or head trauma history, current seizure disorder, concomitant use of drugs that lower the seizure threshold).1, 2, 23, 44, 142, 143 The manufacturer warns that this risk of 0.4% may be up to 4 times that of other currently available antidepressants, including bupropion as extended-release tablets administered at dosages not exceeding 300 mg daily (at a dosage of 400 mg daily, the risk is the same);1, 142 however, the relative risk of seizures with antidepressant agents is not clearly defined and can be affected by a number of factors, including dosage and dosing schedule, concomitantly administered drugs, age, and underlying predisposing factors (e.g., seizure history).1, 2, 23, 24, 44, 108, 141, 142 In addition, most patients in this prospective study received the maximum dosage of 450 mg daily.23 Seizures often occurred during the early phase of bupropion therapy and sometimes occurred several weeks after establishment of dosage.1 Although one study reported that age did not influence the risk of seizures,24 this study did not adequately control for potentially confounding risk factors,108 and it has been suggested that the risk of seizures may decrease with advancing age.108

Other Nervous System Effects Many other adverse nervous system effects of bupropion occur more commonly than seizures.1, 3, 5, 6, 7, 8, 45, 46, 47, 51, 52, 53, 54, 152 Agitation,1, 3, 5, 6, 7, 8, 45, 46, 47, 51, 52, 53, 54, 142 insomnia,1, 3, 5, 7, 45, 46, 47, 51, 52, 53, 142, 152 and anxiety1, 3, 54, 142 occurred in about 32, 19, and 6% of patients, respectively, receiving bupropion.1 These adverse effects and restlessness occur, to some extent, in a substantial number of patients, particularly at the beginning of bupropion therapy.1 Such adverse effects required treatment with sedative/hypnotic drugs in some patients in clinical trials, while discontinuance of bupropion was required in about 2% of patients treated with conventional tablets of bupropion and in about 1 or 3% of patients treated with extended-release tablets of the drug at 300 or

400 mg daily, respectively.1, 45, 142 A limited number of patients with insomnia derived improvement in sleep with concomitant administration of a low dosage of trazodone hydrochloride (e.g., 100 mg daily).121 Impairment in sleep quality1 and asthenia142 each occurred in about 4% of patients receiving bupropion,1, 142 and fatigue occurred in about 5% of patients.1, 3, 45, 46, 51 In patients receiving extended-release tablets of bupropion hydrochloride, agitation occurred in 3 or 9%, insomnia occurred in 11 or 16%, and anxiety occurred in 5 or 6% with 300 or 400 mg daily, respectively.142 In patients receiving bupropion hydrochloride as an adjunct in smoking cessation, insomnia occurred in 29 or 35% of patients receiving 150 or 300 mg daily, respectively, and discontinuance of therapy was required in 0.6% of patients.143, 145 Insomnia occurred in 40 or 45% of patients receiving 300 mg daily of bupropion hydrochloride alone or in combination with transdermal nicotine in a dosage of 21 mg/24 hours, respectively, and discontinuance of therapy was required in 0.8% of patients who received bupropion alone.143 Avoidance of administering bupropion at bedtime or reducing the dosage, if necessary, may minimize insomnia.143 Anxiety occurred in about 11 or 5-8% of patients receiving placebo or bupropion, respectively, as an adjunct in smoking cessation.143, 145

A variety of neuropsychiatric manifestations reportedly have emerged in patients receiving bupropion.1, 142, 143 However, because of the uncontrolled nature of many studies with the drug, it is not possible to provide a precise estimate of the risk of such effects imposed by bupropion therapy.1 Confusion1 and delusions1, 2, 17 occurred in about 8 and 1% of patients, respectively, receiving bupropion.1, 2 In several cases, these and other adverse neuropsychiatric effects, such as hallucinations, psychosis, disturbance in concentration, and paranoia, reportedly abated when bupropion dosage was reduced, although discontinuance of the drug may be necessary.1, 9, 10, 131, 142, 143 Administration of bupropion as an adjunct in smoking cessation or placebo resulted in a generally comparable incidence of adverse neuropsychiatric effects in smokers without a depressive disorder.143

Headache/migraine occurred in up to about 26% of patients receiving bupropion,1, 3, 7, 45, 46, 52, 53, 142 and dizziness (which may be secondary to cardiovascular effects),1, 2, 3, 6, 7, 8, 32, 47, 51, 52, 53, 54, 142 tremor,1, 3, 7, 8, 45, 46, 47, 51, 52, 142 and sedation1 occurred in 22, 21, and 20% of patients, respectively.1 Akinesia/bradykinesia occurred in about 8% of patients receiving the drug.1, 11, 142 Hostility,1, 142 nervousness,142 and sensory disturbance1 occurred in about 6, 5, and 4% of patients, respectively.1, 45 Disturbed concentration,1 somnolence,142 irritability,142 and a decrease in memory142 occurred in about 3% of patients.1, 142 Adverse nervous system effects reportedly occurring in about 1-2% of patients include akathisia,1 pseudoparkinsonism,1, 12 euphoria,1, 142 paresthesia,142 and CNS stimulation.142 Therapy with bupropion as an adjunct in smoking cessation resulted in dizziness, disturbed concentration, dream abnormalities, or nervousness in up to about 10, 9, 5, or 4% of patients, respectively.143 Tremor and somnolence each occurred in up to about 2% of patients receiving bupropion as an adjunct in smoking cessation,143 and abnormality in thinking occurred in about 1% of patients.143

Mania/hypomania reportedly occurred in up to 1% or more of patients receiving bupropion, but a causal relationship to the drug has not been established.1, 13, 14, 15, 16, 44, 142 Limited data suggest that in comparison to tricyclic antidepressants or fluoxetine, mania associated with bupropion is less severe, as indicated by the Clinical Global Impression severity rating.89 Therapy with bupropion as an adjunct in smoking cessation has not resulted in precipitation of mania in smokers without a depressive disorder.143

Psychosis reportedly occurred in less than 1% of patients receiving bupropion, but a causal relationship to the drug has not been established.1, 2, 8, 9, 17, 18, 44, 104, 134 Exacerbation of psychotic behavior in patients with schizoaffective disorder, depressed type also has been reported,104, 117 and catatonia, manifested as mutism, waxy flexibility, staring, rigidity, withdrawal, refusal to eat, and negativism, also has been reported in patients receiving the drug.2, 44, 72 Therapy with bupropion as an adjunct in smoking cessation has not resulted in activation of psychosis in smokers without a depressive disorder.143

In at least one patient who was receiving bupropion for smoking cessation (300 mg daily), extreme irritability, restlessness, anger, anxiety, and cravings occurred soon after cigarettes were withdrawn.145 Within 2 days after discontinuing bupropion and initiating transdermal nicotine replacement therapy, these manifestations resolved.145

Ataxia/incoordination,1, 142 myoclonus,1 dyskinesia,1, 142 dystonia,1, 12, 47, 142 and depression1, 47 occurred in 1% or more of patients receiving bupropion; however, a causal relationship to the drug has not been established.1 Adverse nervous system effects occurring in less than 1% of bupropion-treated patients include vertigo,1, 142 dysarthria,1, 142 hyperkinesia,142 hypesthesia,142 hypertonia,142 memory impairment,1 depersonalization,1, 25, 142 dysphoria,1, 143 mood instability,1 labile emotions,142 paranoia,142 and formal thought disorder;1 however, a causal relationship to the drug has not been established.1 Rarely reported adverse nervous system effects for which a causal relationship has not been established include EEG abnormalities,1, 6, 19, 45, 52, 142 abnormal neurologic exam,1 neuropathy,142 impaired attention,1 neuralgia,142 sciatica,1 derealization,142 and aphasia.1, 142 Coma,1, 142 delirium,1, 2, 12, 26, 27, 28, 44, 104, 110, 111, 142 dream abnormalities,1 hypokinesia,142 extrapyramidal syndrome,142 and unmasking of tardive dyskinesia1, 142 also have been reported, although a causal relationship to bupropion has not been established.1 Exacerbation of tics in patients with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and coexistent Tourette's syndrome has been reported, but such exacerbation also has been observed with stimulants (e.g., amphetamine, methylphenidate) in such patients.2

Suicidal ideation has emerged rarely in patients receiving bupropion, although a causal relationship to the drug has not been established and the possibility of coincidental association cannot be excluded.1, 6, 54, 142 Clinicians should recognize that the inherent risk of suicide in depressed patients may persist until substantial remission in depression occurs.1 (See Cautions: Precautions and Contraindications.)

Metabolic Effects Weight loss exceeding 2.27 kg occurred in about 28% of patients receiving bupropion as conventional tablets.1, 19, 29, 30, 52 Such weight loss occurred in about 23% of patients who were heavier than normal body weight at baseline compared with about 10% of those who were lighter than normal body weight at baseline.29 Patients with weight loss symptomatic of a major depressive episode were not affected differently from patients without weight loss at baseline.29 In patients receiving extendedrelease tablets of bupropion hydrochloride, weight loss exceeding 2.27 kg occurred in about 14 or 19% with dosages of 300 or 400 mg daily, respectively.142

Weight gain occurred in about 14% of patients receiving bupropion as conventional tablets.1, 7, 29, 31 A gain of at least 2.27 kg occurred in 6 or 9% of patients who were overweight or underweight, respectively, at baseline.29 In patients receiving extended-release tablets of bupropion hydrochloride, weight gain exceeding 2.27 kg occurred in about 3 or 2% with dosages of 300 or 400 mg daily, respectively.142

Although most smokers who quit smoking gain weight, bupropion appears to be effective in delaying postcessation weight gain and therefore may be particularly useful in patients greatly concerned about gaining weight after cessation of smoking.152 However, once bupropion therapy is discontinued, the quitting smoker on average will gain an amount of weight that is about the same as if they had not used the drug.152 In patients receiving bupropion for smoking cessation, weight gain from baseline was inversely related to dose at the end of treatment in patients who abstained from smoking, with gains averaging 2.3 kg in those receiving 100 or 150 mg of the drug daily and 1.5 kg in those receiving 300 mg daily; weight gain was 2.9 kg in those receiving placebo.145 However, in those who remained abstinent from smoking 25 weeks after discontinuance of bupropion, weight gain was not dose related, averaging 6.6, 4.4, or 4.5 kg at dosages of 100, 150, or 300 mg daily and 5.5 kg for placebo.145

Cardiovascular Effects

Tachycardia occurred in up to 11% of patients receiving bupropion,1, 2, 6, 7, 47, 142 and cardiac arrhythmias occurred in 5% of patients.1, 2 Palpitations1, 2, 6, 45, 53, 142 occurred in up to about 6% of patients receiving bupropion.142 Hypertension,1, 2, 32, 54 chest pain,1, 33, 142 and flushing1, 46, 142 each occurred in about 4% of patients receiving the drug.1, 2 Hypotension1, 2, 7, 142 and syncope1, 2, 7, 8, 47, 142 occurred in 3 and 1% of patients, respectively.1, 2 Orthostatic hypotension1, 2, 32, 44, 142 also has been reported.1, 142 Dizziness, possibly secondary to cardiovascular effects, has been reported commonly in patients receiving bupropion.1, 2, 6, 7, 8, 32, 47, 51, 53, 54 (See Cautions: Nervous System Effects.) Bupropion generally was well tolerated in a limited number of inpatients with depression and stable congestive heart failure, although an increase in supine blood pressure was associated with the drug that resulted in discontinuance of therapy in some patients because of exacerbation of hypertension present at baseline.142, 143

In patients receiving the drugs as adjunctive therapy in smoking cessation, 300 mg daily of bupropion hydrochloride alone or combined with transdermal nicotine in a dosage of 21 mg/24 hours, hypertension emergent to either treatment was observed in 2.5 or 6.1% of patients, respectively, most of whom had evidence of preexisting hypertension.143 Therapy was discontinued because of hypertension in 1.2% of patients who received the combination of bupropion and transdermal nicotine.143 Palpitations, hypertension, or chest pain occurred in about 2, 1, or less than 1% of patients, respectively, receiving bupropion as an adjunct in smoking cessation.143 In some cases, the hypertension reported was severe. (See Cautions: Precautions and Contraindications.)143

ECG abnormalities (e.g., premature beats, nonspecific ST-T wave changes)1, 19, 34, 45, 47, 142 occurred in less than 1% of patients receiving bupropion, although a causal relationship to the drug has not been established.1 Pallor,1 phlebitis,1, 142 and myocardial infarction1, 142 occurred rarely, but these adverse effects also have not been definitely attributed to the drug.1 Third-degree heart block also has been reported.1, 142

Edema occurred in 1% or more of patients receiving bupropion but has not been definitely attributed to the drug.1, 142 Peripheral edema occurred in less than 1% of patients receiving bupropion, and facial edema occurred rarely.142 Therapy with bupropion as an adjunct in smoking cessation resulted in facial edema in less than 1% of patients.143 In a patient with preexisting cardiomyopathy and hypertension who had received bupropion hydrochloride (300 mg daily) for smoking cessation, cardiac and pulmonary arrest occurred 4 days after completing therapy, and the patient died 9 days later.145 The safety of bupropion for smoking cessation in patients with underlying coronary heart disease remains to be established.146

GI Effects Dry mouth1, 4, 5, 7, 8, 35, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 51, 52, 53, 131, 142, 143 and constipation1, 3, 5, 7, 8, 45, 46, 47, 51, 52, 53, 142, 143 occurred in up to about 28 and 26% of patients, respectively, receiving bupropion, and the possibility exists that such effects may result from adverse nervous system effects;1 however, the anticholinergic activity of the drug reportedly is substantially less than that of tricyclic antidepressants.19, 44, 104 Nausea/vomiting occurred in up to about 23% of patients.1, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 45, 46, 51, 52, 53, 142, 143 Although anorexia occurred in up to about 18% of patients receiving the drug,1, 3, 5, 7, 29, 45, 51, 142, 143 an increase in appetite was reported in up to about 4% of patients.1, 4, 29, 45, 53, 143 Abdominal pain occurred in up to about 9% of patients receiving bupropion.142, 143 Diarrhea occurred in up to about 7% of patients1, 7, 47, 53, 142, 143 and dyspepsia,1 increased salivation,1, 7, 47, 51, 142 and gustatory disturbance1, 51, 142, 143 each occurred in up to about 3% of patients receiving bupropion.1 Dysphagia1, 142 occurred in up to about 2% of patients receiving bupropion.142 Mouth ulcer occurred in 2% of patients receiving bupropion as an adjunct in smoking cessation.143

Stomatitis has been reported in 1% or more of patients receiving bupropion, but has not been definitely attributed to the drug.1 Thirst disturbance,1, 142, 143 gum irritation,1 and oral edema1 were reported in less than 1% of patients receiving the drug, but a causal relationship also has not been established.1 Rectal complaints,1 colitis,1, 142 GI bleeding,1, 142 intestinal perforation,1, 142 stomach ulcer,1, 142 gingivitis,142 lingual edema,142 glossitis,1 and esophagitis1, 142 have occurred rarely but have not been definitely attributed to bupropion.1

Dermatologic and Sensitivity Reactions Excessive sweating occurred in up to about 22% of patients receiving bupropion.1, 51, 52, 53, 142 Rash,1, 6, 48, 53, 142, 143 pruritus,1, 52, 142, 143 and urticaria1, 142, 143 occurred in up to about 8, 4, and 2% of patients, respectively.1 Cutaneous temperature disturbance occurred in about 2% of patients receiving the drug.1, 142 Nonspecific rashes occurred in 1% or more of patients receiving bupropion,1 and alopecia,1 photosensitivity,142 and dry skin1 have occurred in less than 1% of patients receiving the drug, but these effects have not been definitely attributed bupropion.1 Although a causal relationship has not been established, a change in hair color,1 hirsutism,1, 142 maculopapular rash,142 and acne1 have been reported rarely,1 and Stevens-Johnson syndrome,1, 142 angioedema,1, 142 exfoliative dermatitis,1, 142 and ecchymosis1, 142 also have been reported. Symptoms resembling serum sickness, including arthralgia, myalgia, and fever with rash and other symptoms suggestive of delayed hypersensitivity, have been reported in association with bupropion. 1, 142, 143 Anaphylactoid reactions (e.g., pruritus, urticaria, angioedema, dyspnea) that required medical management occurred rarely in patients receiving bupropion;143, 145 other concomitantly administered drugs may have confounded attributing these effects to bupropion.145 Application site reaction occurred in 15% of patients receiving bupropion combined with transdermal nicotine as adjunctive therapy in the cessation of smoking.143

Dry skin or allergic reaction occurred in about 2 or 1% of patients receiving bupropion as an adjunct in smoking cessation.143

Ocular and Otic Effects Blurred vision occurred in about 15% of patients receiving bupropion.1, 3, 7, 8, 45, 47 Amblyopia occurred in up to about 3% of patients receiving bupropion.142 Adverse ocular effects reported in less than 1% of bupropion-treated patients include visual disturbance,1 dry eye,142 and mydriasis;1, 142 however, a causal relationship to the drug has not been established.1 Diplopia occurred rarely but has not been definitely attributed to bupropion.1, 142

Tinnitus occurred in up to about 6% of patients receiving bupropion.1, 3, 37, 142, 143 Auditory disturbance occurred in 5% of patients receiving the drug.1 Deafness has occurred but has not definitely been attributed to bupropion.142

Musculoskeletal Effects Myalgia1, 142, 143 and arthralgia1, 142, 143 occurred in up to about 6 and 5%, respectively, of patients receiving bupropion.142, 143 Arthritis and muscle spasm or twitch occurred in up to about 3 and 2% of patients, respectively, receiving the drug.1, 142 Musculoskeletal chest pain has been reported rarely in less than 1% of patients receiving bupropion.1, 142 Leg cramps,142 muscle weakness,1, 142 and muscle rigidity/fever/rhabdomyolysis1, 142 also have been reported, although a causal relationship also has not been established.1 Neck pain occurred in 2% of patients receiving bupropion as an adjunct in smoking cessation.143

Respiratory Effects Pharyngitis occurred in up to about 11% of patients receiving bupropion.142, 143 Upper respiratory complaints occurred in about 5% of patients receiving bupropion.1 Sinusitis and an increase in coughing each occurred in up to about 3% of patients receiving bupropion.142, 143 Although a causal relationship has not been established, bronchitis1, 142 and shortness of breath/dyspnea1, 46, 142, 143 each have occurred in less than 1% of patients receiving bupropion,1 and respiratory rate or rhythm disorder,1 bronchospasm,142 pneumonia,1, 142 and pulmonary embolism1, 142 have occurred rarely.1 Therapy with bupropion as an adjunct in smoking cessation resulted in rhinitis, bronchitis, or dyspnea in 12, 2, or 1% of patients, respectively.143

Genitourinary Effects Menstrual complaints occurred in about 5% of patients receiving bupropion,1, 35, 36, 44, 104 and impotence1, 3, 142 and decreased libido1, 2, 45, 142 each occurred in about 3% of patients.1, 2 Urinary frequency,1, 142 urgency,142 and retention1, 53, 142 occurred in up to about 5, 2, and 2% of patients, respectively, receiving the drug.1 Vaginal hemorrhage occurred in up to about 2% of female patients receiving bupropion.142 Urinary tract infection1, 142 occurred in up to about 1% of patients receiving bupropion.142 Nocturia,1, 46 increased libido,1, 2, 142 and a decrease in sexual function1, 2 have occurred in 1% or more of patients receiving bupropion, although a casual relationship to the drug has not been established.1, 2 Although not definitely attributed to the drug, vaginal irritation,1 vaginitis,142 testicular swelling,1 polyuria,142 painful erection,1, 142 retarded ejaculation,1 and frigidity1 have been reported in less than 1% of bupropion-treated patients,1 and dysuria,1, 142 enuresis,1 urinary incontinence,1, 142 glycosuria,1, 142 menopause,1, 142 ovarian disorder,1salpingitis,142 pelvic infection,1 cystitis,1, 142 dyspareunia,1, 142 and painful or abnormal ejaculation1 have occurred rarely.1 Clitoral priapism and sexual arousal prolonged to about 24 hours reportedly occurred in at least one female receiving bupropion; she previously had experienced anorgasmia while receiving sertraline.87

Other Adverse Effects Infection occurred in up to about 9% of patients receiving bupropion.142 Hot flashes142, 143 and pain1, 142 each occurred in up to about 3% of patients receiving the drug.142 Fever/chills occurred in up to about 2% of patients receiving bupropion.1, 142 Accidental injury or epistaxis each occurred in about 2% of patients receiving bupropion as an adjunct in smoking cessation.143

Flu-like symptoms1, 3, 49 occurred in 1% or more of patients receiving bupropion but that have not been definitely attributed to the drug.1 Although a causal relationship also has not been established, gynecomastia,1, 142 abnormal liver function test results,1, 23, 40, 142 liver damage/jaundice,1, 142 toothache,1 and bruxism1, 142 have been reported in less than 1% of bupropion-treated patients,1 and hormone concentration change,1 lymphadenopathy,1, 142 anemia,1, 142 pancytopenia,1, 142 epistaxis,1 body odor,1 surgically related pain,1 drug reaction,1 malaise,142 and overdose1, 6, 19 have occurred rarely in patients receiving the drug.1 Syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion (SIADH),1, 142 hyperglycemia,142, 143 hypoglycemia,1, 142 hepatitis,1, 142 thrombocytopenia,1, 142 leukocytosis,1, 142 and leukopenia1, 142 also have been reported, although these adverse effects have not been definitely attributed to bupropion.1 Eosinophilia has also been reported.136

Precautions and Contraindications

Because of the possibility of suicide in depressed patients, bupropion should be prescribed in the smallest quantity consistent with good patient management.1, 142 Suicidal ideation may persist until substantial remission of the depressive disorder occurs.1, 142

Hypertension (sometimes severe) has been reported in patients with or without evidence of preexisting hypertension who were receiving bupropion alone or in combination with nicotine replacement therapy.143 Bupropion should be used cautiously in patients with cardiovascular disease as the safety of bupropion in patients with a recent history of myocardial infarction or unstable heart disease has not been established because of a lack of clinical experience.1, 142, 143 However, patients who developed orthostatic hypotension with tricyclic antidepressants have tolerated bupropion well.1, 8, 19, 38, 44, 103, 130, 134, 142, 143 Since hypertension occurred with the combination of bupropion and transdermal nicotine as adjunctive therapy in smoking cessation, monitoring for hypertension as an adverse effect is recommended in recipients of such concurrent therapy.143 (See Cautions: Cardiovascular Effects.)

Bupropion should be used with extreme caution in patients with severe hepatic impairment and the dosing interval should be increased. (See Dosage and Administration: Dosage.)1, 142, 143 Bupropion also should be used with caution in patients with mild to moderate hepatic impairment and consideration should be given to increasing the dosing interval. (See Dosage and Administration: Dosage)1, 142, 143 Bupropion is extensively metabolized in the liver, and pharmacokinetcs of the drug and its metabolites may be altered in patients with hepatic impairment.1, 142, 143 The effects of renal impairment on the elimination of bupropion have not been evaluated.143 However, the manufacturer suggests that bupropion be used with caution in such patients because of potential increased accumulation of the drug and its active metabolites, which principally are excreted in urine.143 Patients with hepatic or renal impairment who receive bupropion should be closely monitored for adverse effects.143

Patients should be informed that since alcohol may alter the seizure threshold, minimal drinking is advisable while abstinence is optimal during bupropion therapy.1, 142 Additionally, patients should be informed that if they discontinue alcohol or sedatives (e.g., benzodiazepines) abruptly during bupropion therapy, there is an increased risk of seizures.1, 142, 143 Patients also should be cautioned that bupropion may impair their ability to perform activities requiring mental alertness or physical coordination (operating machinery, driving a motor vehicle) and to avoid such activities until they experience how the drug affects them.1, 142 Counseling about bupropion as an adjunct in smoking cessation should include review of information provided by the manufacturer for patients.143 Ensuring that patients read the instructions provided and answering their questions are important.143 Patients should be warned that the preparation of bupropion for use as an adjunct in smoking cessation contains

the same drug as the preparation of bupropion for use in the treatment of depressive disorders and that they should not receive such preparations in combination.143

Patients should be advised to discontinue taking bupropion and to consult a clinician if they experience allergic, anaphylactoid or anaphylactic symptoms (e.g., skin rash, pruritus, hives, chest pain, edema, shortness of breath) during treatment with the drug.142, 143 Anaphylactic or anaphylactoid reactions with symptoms including pruritus, urticaria, angioedema, and dyspnea have occurred in clinical trials of bupropion.142, 143 Also, rare reports of erythema multiforme, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and anaphylactic shock associated with use of bupropion have occurred.142, 143

Patients receiving bupropion should be advised to notify their clinician if they are taking or plan to take nonprescription (over-the-counter) or prescription drugs.1, 142 The metabolism of bupropion and other drugs might be affected by such concomitant use.1, 142

Because bupropion therapy has been associated with weight loss exceeding 2.27 kg at twice the incidence with tricyclic antidepressants or placebo in comparable patients and because fewer patients gained weight with bupropion than with tricyclic antidepressants (9 versus 35%), such effects should be considered in patients whose depression includes weight loss as a major manifestation.1, 29, 142

As with other antidepressants, the possibility should be considered that bupropion may precipitate manic attacks in patients with bipolar disorder.1, 14, 86, 142, 143 Another consideration is that in other susceptible patients the drug may activate latent psychosis.1, 9, 142, 143

The hepatotoxic potential, if any, of bupropion in humans is unclear.1 Hepatic hyperplastic nodules and hepatocellular hypertrophy were increased in incidence in rats chronically administered large doses of bupropion,1, 142 and various histologic changes in the liver and mild hepatocellular injury suggested by laboratory tests occurred in dogs chronically administered large doses of the drug.1, 142 However, despite scattered abnormalities in liver function test results observed during clinical trials with bupropion, there currently is no clinical evidence that the drug is a hepatotoxin in humans.1, 23, 40, 142

The manufacturer states that the incidence of seizures during bupropion therapy has been estimated to exceed, by as much as fourfold (e.g., 0.4 versus 0.1%), that observed during therapy with other currently available antidepressants, including bupropion as extended-release tablets administered at dosages not exceeding 300 mg daily.1, 142 However, the relative risk of seizures with various antidepressants,

including bupropion, has not been clearly defined,1, 2, 23, 24, 44, 108, 141, 142 and the incidence of seizures at dosages of 400 mg daily as extended-release tablets increases to 0.4%.142 (See Seizures under Cautions: Nervous System Effects.) The risk of seizures may be higher with sudden and large increase in dosage.1, 8 Estimations of the incidence of seizures increase almost tenfold with dosages between 450-600 mg daily.1, 142, 143 Because of this disproportionate increase in the incidence of seizures and in consideration of interindividual variability in the metabolism and elimination of drugs, bupropion dosage should be titrated cautiously.1, 141, 142 While many seizures occurred early in the course of therapy, some seizures have occurred after several weeks of fixed dosage bupropion therapy.1 The manufacturer states that bupropion should be discontinued and not restarted in patients who experience a seizure during bupropion therapy.1, 142

Besides dose, factors that are predispositions to the development of seizures (e.g., history of head trauma or prior seizure, CNS tumor, the presence of severe hepatic cirrhosis, concomitant drugs that lower seizure threshold) appear to be strongly associated with the risk of seizures with bupropion.1, 8, 142, 143 Presence of such predisposing factors characterized approximately one-half of the patients affected with a seizure.1, 2, 6, 19, 20, 21, 23, 24, 44, 108 In addition, the patient's clinical situation may be characterized by circumstances that are associated with an increase in the risk of seizures (e.g., diabetes mellitus treated with oral antidiabetic agents or insulin, excessive use of alcohol or sedatives [e.g., benzodiazepines], abrupt withdrawal from alcohol or other sedatives, use of over-the-counter stimulants and anorexigenic agents, addiction to opiate agonists, cocaine, or stimulants).1, 142, 143 Use of bupropion should be particularly cautious in patients with a history of seizure, cranial trauma, or other relevant factors or who are receiving other drugs (e.g., antipsychotics, other antidepressants, theophyiline, systemic corticosteroids) or therapeutic regimens (e.g., abrupt discontinuation of a benzodiazepine) that lower the seizure threshold.1, 142, 143

For patients being treated with bupropion for psychiatric disorders other than nicotine dependence, minimization of the risk of seizures may be possible with measures that were retrospectively identified, including restriction of the total dosage to 400 or 450 mg daily as extended-release or conventional tablets, respectively, administration of the daily dose in 3 divided doses each not exceeding 150 mg when the conventional tablets are used or in 2 divided doses each not exceeding 200 mg when extended-release tablets are used so that high peak concentrations of bupropion and/or its metabolites are avoided, and upward titration of dose in a gradual manner.1, 142 For patients receiving bupropion for smoking cessation, such measures for minimizing the risk of seizures include restriction of the total dosage to 300 mg daily, administration of the daily dose recommended for most patients (i.e., 300 mg daily) in divided doses (i.e., 150 mg twice daily), and restriction of each dose to 150 mg so that high peak concentrations of bupropion and/or its metabolites are avoided.143 The decision to use bupropion as an adjunct in smoking cessation must involve consideration of whether the patient is at risk for seizures through the presence of factors that are predispositions to the development of seizures, drugs already being taken, or clinical situation of the patient.143 The dosage of bupropion as an adjunct in smoking

cessation should not exceed 300 mg daily because the risk of seizures associated with the drug depends on dose.143 If patients experience a seizure while receiving bupropion for smoking cessation, the drug should be discontinued and should not be restarted.143

Bupropion is contraindicated in patients with a seizure disorder.1, 142, 152 The manufacturer states that current or past diagnosis of bulimia or anorexia nervosa also contraindicate bupropion therapy because of the increased incidence of seizures observed in such patients treated with conventional bupropion tablets.1, 21, 22, 24, 39, 142, 143, 152 Because the incidence of seizures with bupropion depends on dose, the preparation of bupropion for use as an adjunct in smoking cessation is contraindicated in patients treated with other preparations of the drug.143 Bupropion is contraindicated in patients undergoing abrupt discontinuance of alcohol or sedatives (e.g., benzodiazepines).1, 142, 143 Bupropion therapy also is contraindicated in patients currently receiving, or having recently received (i.e., within 2 weeks), monoamine oxidase (MAO) inhibitor therapy1, 142, 152 and in patients with known hypersensitivity to the drug or to any other component in the formulation.1, 142

Pediatric Precautions Safety and efficacy of bupropion in children younger than 18 years of age have not been established.1, 142, 143However, the drug has been used in a limited number of children 7-16 years of age with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) without unusual adverse effect, and use of the antidepressant currently is included in recommendations of the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) as possible second-line therapy for the treatment of this condition as directed by clinicians familiar with its use.2, 44, 79, 80, 134, 158 In addition, extended-release bupropion currently is included in the US Public Health Service (USPHS) guideline for consideration in the treatment of nicotine (tobacco) use and dependence in adolescents when there is evidence of nicotine dependence and a desire to quit the use of tobacco.152 Before instituting bupropion therapy though, clinicians should be confident of the patient's dependence on tobacco and intention to quit, given the psychosocial and behavioral aspects of smoking in adolescents.152 Clinicians should consider such factors as degree of dependence on nicotine, number of cigarettes smoked daily, and the patient's weight.152 While pharmacotherapy (e.g., bupropion, nicotine replacement therapy) can be considered for adolescents dependent on nicotine and there currently is no evidence of harm from such therapy in the pediatric population, the USPHS currently only recommends consideration of counseling and behavioral interventions in younger children.152 Clinicians in a pediatric setting also should offer smoking cessation advice and interventions to parents to limit exposure of children to second-hand smoke.152

Tobacco use in the pediatric population in the US is a major concern.152 It is estimated that more than 6000 children and adolescents try their first cigarette each day in the US, and that more than 3000

become daily smokers each day.152 Among adults who have ever smoked, about 90% tried their first cigarette and about 70% were daily users by age 18 years.152 Because tobacco use often begins during preadolescence, clinicians should routinely assess and intervene in this population.152 Young individuals vastly underestimate the addictiveness of nicotine.152