War and Peace Rext

Diunggah oleh

Rahma LeonHak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

War and Peace Rext

Diunggah oleh

Rahma LeonHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

August 23, 2007 | 8:11 a.m.

Leo Tolstoy. +Enlarge Getty Images. Two new translations of Leo Tolstoys War and Peace will be published in the United States this fall, one claiming to be the definitive version and the other claiming to be the long lost, more accessible first draft. The first translation, out on Knopf in October, is by all-stars Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky. It clocks in at 1,219 pages, and according to editor LuAnn Walther, it represents what Tolstoy would have wanted us to read if he were alive today. The other one, translated by the lesser known Andrew Bromfield, will be published by Ecco in September; it is being marketed as the original version of Tolstoys classic, one that has never been seen in this country. This edition comes with picturesillustrations commissioned by Tolstoy himselfand it is about four hundred pages shorter than Knopfs. The two books are scheduled to arrive in stores about a month apart, and in the grand tradition of Russian confrontation, Ecco and Knopf are ready to duel. Knopf has mounted an aggressive effort to discredit Eccos edition, arguing that it is not an original version at all but a dumbed down misrepresentation that violates Tolstoys work and misleads readers. Ms. Walther told Publishers Weekly last month that Ecco was making a serious mistake, while Mr. Pevear has written an open letter to journalists at her behest, in which he condemns Eccos philistine attitude towards Tolstoy as an artist and warns readers against falling for their sales pitch. In an interview Monday, Ecco vice president and publisher Daniel Halpern said his only aim is to offer Toltoy fans and scholars a potentially enlightening text, while giving new, more casual readers a chance to read War and Peace without having to slog through all of Tolstoys philosophical digressions. Ecco had put out two well-received translations when they got started on Tolstoyone of Death in Venice, the other Don Quixoteand Mr. Halpern wanted to keep the series

going. So it was decided that Ecco's next project would be War and Peace, and the Ecco staff went looking for a translator. At first, as Mr. Halpern tells it, they wanted Mr. Pevear and Ms. Volokhonsky, the celebrated husband-and-wife duo whose profile had recently swelled when Oprah Winfrey selected their translation of Anna Karenina for her book club. According to Mr. Halpern, he was close to finalizing a deal with the couple when they had a change of heart and decided to stay with Knopf instead. (Asked about Pevear and Volokhonskys flirtation with Ecco, Ms. Walther suppressed a laugh and went through the impressive list of Russian classics that the couple had already translated for Knopf when they started War and Peace). With that, the search committee at Ecco reconvened and eventually settled on Mr. Bromfield, who had translated a pile of contemporary Russian writers, among them Boris Akunin and Victor Pelevin. It turned out Mr. Bromfield was already working on it for a British imprint of HarperCollins called Fourth Estate. He wasnt working on the well-known version of the novel, though, but an early draft, first made available to the Russian public in 2000 by a philologist-turned-publisher named Igor Zakharov. Intrigued, Mr. Halpern swiftly arranged for Ecco to publish the book in the United States. This version of the book was based on three serialized chapters Tolstoy published in a Russian journal in 1865 and 1866. According to a note at the front of the Ecco edition and the introduction by Nikolai Tolstoy, who is vaguely related to the authorTolstoy used these chapters as the foundation for a draft he completed in December 1866. At that point, he is said to have written The End on the last page of the manuscript, but soon after, he changed his mind, left Moscow for his country estate, and for three years made extensive revisions that would lead to the publication of the complete work, totaling six volumes, in 1869. This version, for the most part, served as the basis for the widely used English translation by Louise and Aylmer Maude, published in the 1920s. Mr. Zakharov, the Russian publisher, had taken quite a beating from critics when he put out this edition of War and Peace in Moscow. The text of the book, totaling about 700 pages, was adapted from an academic monograph compiled over the course of 50 painstaking years by a Russian Tolstoy scholar and published in 1983. The general public had been largely unaware of this first draft until Mr. Zakharov decided to clean it up that is, remove all the cumbersome footnotes, brackets, and variants that its editor had lovingly inserted for the benefit of academiaand repackage it for trade. Im a popularizer, Mr. Zakharov said in an interview, speaking to the Observer in Russian from Berlin. I see something interesting and I start waving my hands and yelling hey, hey, everyone come here! Ive got something here! Maybe youll like it too!

Mr. Zakharov spent a month editing Zaidenshnurs monograph and printed 5,000 copies of it when he was done. On the back, he included a rousing editorial statement declaring that his version of War and Peace was better, shorter, and above all more authentic than the one people were used to. Twice as short, four times as interesting, he promised. More peace, less war. Almost no philosophical digressions or incomprehensible French. A happy ending: Prince Andrei and Petya Rostov remain alive. Before long, Mr. Zakharov was at the center of a huge wave of protest, objection, and fury of the wildest variety. He even participated in a public trial of the book, shown on national television, during which he fielded criticisms from various Tolstoy scholars (Mr. Zakharov recalls, One person said, Igor, how could you? You are in Russia! If a stick of butter says real on it, then everyone knows it is definitely margarine! I hadnt thought of that.)

Mr. Zakharov was insulted by the reaction: The hell with you all, I said to them, let them read it overseasthere are normal people over there, who actually read books. With the help of his literary agent (who also represents Mikhail Gorbachev), Mr. Zakharov has since gotten his War and Peace translated into fourteen languages. Mr. Zakharov said that seeing the English translation, which appeared in the UK last April, made him feel like Napoleon. Mr. Halpern and his staff at Ecco have deliberately distanced themselves from Mr. Zakharov, avoiding his rhetoric as they prepare to release the book; as a result, according to Mr. Halpern, the venom coming from Knopf is misplaced. All the stuff in [Pevears] letter, the headlines that he quotes in there, we chose not to use it, Mr. Halpern said. Actually, the press release Ecco issued in advance of the books publication does quote Mr. Zakharovs remarks quite prominently, but qualifies them by saying that he went a little overboard. (Mr. Zakharov said he does not blame the American editors for abandoning his sales pitch: Sometimes understatement is better than running out and beating your chest.) Still, Mr. Halpern said, Ecco is not claiming that their book will replace the canonical version. In fact, he said, Mr. Bromfield is about to start work on a translation of the actual War and Peacethat is, the long one everyone knowsand in all likelihood Ecco will be publishing it when hes done.

Its confusing until you just sit down and read the introduction to our book, Mr. Halpern said, which clearly LuAnn hadnt done. Tolstoy scholars, meanwhile, seem distrustful of Eccos original version, pointing out that Tolstoys work on the book was too scattered for there to be any one authoritatively first draft.

This is certainly not a duel, said Donna Orwin, who used to edit the Tolstoy Studies Journal from the University of Toronto, because the Bromfield version of War and Peace really is a fraud. It is an early version of War and Peace, thats certainly true, but its not War and Peace. Still, most of the academics contacted for this story were wearily disinterested in the controversy that has erupted over the two translations. This is purely commercial bullshit, said Stanford Slavist Gregory Freidin. I do not think it deserves anyones attention. It is about which car gets the best gas mileage, that kind of thing. Anyway, it is a great book though.

Tags: Media | Ecco Press | Leo Tolstoy | The Knopf Publishing Group

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- Lieutenant Commander Anthony DiNozzo Pt.1Dokumen23 halamanLieutenant Commander Anthony DiNozzo Pt.1hurricanesea81% (21)

- The Gulag Archipelago: The Authorized AbridgementDari EverandThe Gulag Archipelago: The Authorized AbridgementPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (491)

- Kafka-Amerika-The Man Who Disappeared PDFDokumen203 halamanKafka-Amerika-The Man Who Disappeared PDFVandana Sharma100% (3)

- Wise Thoughts for Every Day: On God, Love, the Human Spirit, and Living a Good LifeDari EverandWise Thoughts for Every Day: On God, Love, the Human Spirit, and Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (11)

- Defending Middle-Earth: Tolkien: Myth and ModernityDari EverandDefending Middle-Earth: Tolkien: Myth and ModernityPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (20)

- Short Stories Isaac BabelDokumen112 halamanShort Stories Isaac BabelArpanChoudhuryBelum ada peringkat

- Annotated Bibliography 1Dokumen8 halamanAnnotated Bibliography 1api-272612175100% (1)

- Vasilii Yakovlevich Eroshenko (1890-1952)Dokumen11 halamanVasilii Yakovlevich Eroshenko (1890-1952)kalwisti100% (1)

- Anna Karenina DownloadDokumen3 halamanAnna Karenina DownloadLaurie BrooksBelum ada peringkat

- The Road to Middle-Earth: How J. R. R. Tolkien Created a New MythologyDari EverandThe Road to Middle-Earth: How J. R. R. Tolkien Created a New MythologyPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (8)

- The Five Paragraph Operations OrderDokumen15 halamanThe Five Paragraph Operations OrderJohn C BooneBelum ada peringkat

- Fathers and Sons PDFDokumen275 halamanFathers and Sons PDFSifar SharmaBelum ada peringkat

- Our Friend Ethel Lilian Boole/VoynichDokumen75 halamanOur Friend Ethel Lilian Boole/VoynichgglocksterBelum ada peringkat

- 03 12kowallis-Form130131 KopieDokumen21 halaman03 12kowallis-Form130131 KopieChiou YishengBelum ada peringkat

- Henry Wadsworth LongfellowDokumen10 halamanHenry Wadsworth LongfellowLaura RotaruBelum ada peringkat

- Dostoevsky, F - Crime and Punishment (Random, 1992)Dokumen329 halamanDostoevsky, F - Crime and Punishment (Random, 1992)Kamijo Yoitsu100% (2)

- NS 3 - 130-151 - N and Byron - D. S. ThatcherDokumen22 halamanNS 3 - 130-151 - N and Byron - D. S. ThatcherTiago LacerdaBelum ada peringkat

- Translating Topol: Kafka, The Holocaust, and HumorDokumen15 halamanTranslating Topol: Kafka, The Holocaust, and HumorAlex ZuckerBelum ada peringkat

- Composition and Publication History: Night in 1839Dokumen2 halamanComposition and Publication History: Night in 1839Veda KumarBelum ada peringkat

- Gogol From the Twentieth Century: Eleven EssaysDari EverandGogol From the Twentieth Century: Eleven EssaysPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1)

- Creating Anna Karenina: Tolstoy and the Birth of Literature's Most Enigmatic HeroineDari EverandCreating Anna Karenina: Tolstoy and the Birth of Literature's Most Enigmatic HeroinePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5)

- Questions of Reception and Transmigration in Translation - RAGUETDokumen23 halamanQuestions of Reception and Transmigration in Translation - RAGUETHeather ThompsonBelum ada peringkat

- Einar Haugen - Ibsen's Drama - Author To Audience (1979) PDFDokumen72 halamanEinar Haugen - Ibsen's Drama - Author To Audience (1979) PDFIngrid RicciBelum ada peringkat

- Cambridge Companion To BorgesDokumen7 halamanCambridge Companion To BorgesMaría SolariBelum ada peringkat

- The Essential Russian Plays & Short Stories: Chekhov, Dostoevsky, Tolstoy, Gorky, Gogol & Others (Including Essays and Lectures on Russian Novelists)Dari EverandThe Essential Russian Plays & Short Stories: Chekhov, Dostoevsky, Tolstoy, Gorky, Gogol & Others (Including Essays and Lectures on Russian Novelists)Belum ada peringkat

- The Function of The Poet and Other Essays by Lowell, James Russell, 1819-1891Dokumen99 halamanThe Function of The Poet and Other Essays by Lowell, James Russell, 1819-1891Gutenberg.orgBelum ada peringkat

- Transtromer Squabbles - TLSDokumen4 halamanTranstromer Squabbles - TLScabojandiBelum ada peringkat

- Nabokov Wilson and The Dead PoetsDokumen18 halamanNabokov Wilson and The Dead PoetskkokinovaBelum ada peringkat

- Tales of The Wilderness by Pilniak, Boris, 1894-1937Dokumen115 halamanTales of The Wilderness by Pilniak, Boris, 1894-1937Gutenberg.orgBelum ada peringkat

- The Gospel in Tolstoy: Selections from His Short Stories, Spiritual Writings & NovelsDari EverandThe Gospel in Tolstoy: Selections from His Short Stories, Spiritual Writings & NovelsPenilaian: 5 dari 5 bintang5/5 (2)

- Vladimir Propp-Theory & History of Folklore (Theory and History of Literature) - University of Minnesota Press (1984)Dokumen336 halamanVladimir Propp-Theory & History of Folklore (Theory and History of Literature) - University of Minnesota Press (1984)Rafael Antunes100% (4)

- Mandelstam Osip The Noise of TimeDokumen260 halamanMandelstam Osip The Noise of TimeSan Ban Castro100% (7)

- 12980-Article Text-10418-1-10-20160704Dokumen15 halaman12980-Article Text-10418-1-10-20160704Somya SinghBelum ada peringkat

- Ossendowski's Sources (Marco Pallis) PDFDokumen12 halamanOssendowski's Sources (Marco Pallis) PDFIsrael100% (1)

- The Metamorphosis - Franz KafkaDokumen318 halamanThe Metamorphosis - Franz Kafkajanelle johnsonBelum ada peringkat

- Russian Fairy Tales: A Choice Collection of Muscovite Folk-loreDari EverandRussian Fairy Tales: A Choice Collection of Muscovite Folk-loreBelum ada peringkat

- Penguinisation HI RemDokumen8 halamanPenguinisation HI RemSoumyadeep GhoshBelum ada peringkat

- It Will Yet Be Heard: A Polish Rabbi's Witness of the Shoah and SurvivalDari EverandIt Will Yet Be Heard: A Polish Rabbi's Witness of the Shoah and SurvivalBelum ada peringkat

- Russian Fairy Tales: A Choice Collection of Muscovite Folk-loreDari EverandRussian Fairy Tales: A Choice Collection of Muscovite Folk-loreBelum ada peringkat

- Jakob Kerkhoven Third ExistenceDokumen339 halamanJakob Kerkhoven Third ExistenceGabriel Augusto100% (3)

- Nietzsche S LibraryDokumen86 halamanNietzsche S LibraryFilosofia FilosofareBelum ada peringkat

- 1634-Article Text-7064-1-10-20170530 PDFDokumen11 halaman1634-Article Text-7064-1-10-20170530 PDFigodany72Belum ada peringkat

- Vladimir Nabokov's Solus Rex and The Ultima Thule ThemeDokumen15 halamanVladimir Nabokov's Solus Rex and The Ultima Thule Themelgarrison089Belum ada peringkat

- Inspired by Hungarian Poetry - British Poets in Conversation With Attila József PDFDokumen114 halamanInspired by Hungarian Poetry - British Poets in Conversation With Attila József PDFBalassi IntézetBelum ada peringkat

- Asger Jorn The Human AnimalDokumen1 halamanAsger Jorn The Human AnimalRobert E. HowardBelum ada peringkat

- Essential Novelists - Nikolai Gogol: the foundations of Russian realismDari EverandEssential Novelists - Nikolai Gogol: the foundations of Russian realismBelum ada peringkat

- Donne and The New PhilosophyDokumen312 halamanDonne and The New Philosophyparadoxian2Belum ada peringkat

- Ibsen As A Social ReformerDokumen26 halamanIbsen As A Social Reformerfidsin100% (1)

- Abramovich PDFDokumen20 halamanAbramovich PDFAnonymous OuZdlEBelum ada peringkat

- The Legend of BeowulfDokumen27 halamanThe Legend of BeowulfRahma LeonBelum ada peringkat

- Berita Kepada KawanDokumen31 halamanBerita Kepada KawanRahma LeonBelum ada peringkat

- Scores (High School) : (Score: 0-100)Dokumen5 halamanScores (High School) : (Score: 0-100)Rahma LeonBelum ada peringkat

- Ayu Narrative TextDokumen1 halamanAyu Narrative TextRahma LeonBelum ada peringkat

- Computergames World Magazine Jan06Dokumen124 halamanComputergames World Magazine Jan06Andrei Lupescu100% (1)

- 24 S&P26 WargamerDokumen72 halaman24 S&P26 Wargamerk_ppa1981100% (3)

- Class 5 The Struggle For Independence NotesDokumen3 halamanClass 5 The Struggle For Independence NotesSohum Venkatadri0% (1)

- Multigenre ProjectDokumen11 halamanMultigenre Projectapi-237126906Belum ada peringkat

- History - Rome and Romania, 27 BC - 1453 AdDokumen248 halamanHistory - Rome and Romania, 27 BC - 1453 Adglnutza100% (1)

- FarewellDokumen209 halamanFarewellEdna Tal ElhasidBelum ada peringkat

- Serchopi Dance From Iran-1Dokumen2 halamanSerchopi Dance From Iran-1api-454675280Belum ada peringkat

- NTSEDokumen42 halamanNTSEtranquil_452889939100% (1)

- (Wab) Successor Empire Armies (265-46 BC) - Jeff JonasDokumen8 halaman(Wab) Successor Empire Armies (265-46 BC) - Jeff JonasLawrence WiddicombeBelum ada peringkat

- Ôn Thi Đh Không Buồn Ngủ - Anh Luôn Muốn Điều Tốt Nhất Cho Mấy ĐứaDokumen18 halamanÔn Thi Đh Không Buồn Ngủ - Anh Luôn Muốn Điều Tốt Nhất Cho Mấy ĐứaHà Như KhuyênBelum ada peringkat

- The Codification of International Law 2Dokumen40 halamanThe Codification of International Law 2doctrineBelum ada peringkat

- American Infantry Divisional Formations 1941-1945Dokumen52 halamanAmerican Infantry Divisional Formations 1941-1945Bill BaseyBelum ada peringkat

- Wargames Illustrated #091Dokumen56 halamanWargames Illustrated #091Анатолий Золотухин100% (1)

- Snowden Reveals UFO DocumentsDokumen1 halamanSnowden Reveals UFO DocumentsMidhun DBBelum ada peringkat

- It Is A Story That Can Break Nationalistic Barriers That Are An Obstacle For Prosperity of Federation Bosnia and HerzegovinaDokumen4 halamanIt Is A Story That Can Break Nationalistic Barriers That Are An Obstacle For Prosperity of Federation Bosnia and HerzegovinaBoris KaeskiBelum ada peringkat

- Kurdish AwakeningDokumen16 halamanKurdish AwakeningZeinab KochalidzeBelum ada peringkat

- Chinese Revolution The Biggest Genocide On Planet Earth, Communism and The Jews, Mao Tse Tung and Rothschild Funds - Capt Ajit VadakayilDokumen64 halamanChinese Revolution The Biggest Genocide On Planet Earth, Communism and The Jews, Mao Tse Tung and Rothschild Funds - Capt Ajit VadakayilAnonymous00007Belum ada peringkat

- Part One: Reading (14Pts) A) Comprehension (7Pts)Dokumen9 halamanPart One: Reading (14Pts) A) Comprehension (7Pts)nour edhohaBelum ada peringkat

- 00 Gac 3eDokumen10 halaman00 Gac 3emrbogey2220% (1)

- In MemoryDokumen13 halamanIn MemoryMary ReshmaBelum ada peringkat

- Willa B. BrownDokumen1 halamanWilla B. BrownCAP History LibraryBelum ada peringkat

- My Father's Brain, Jonathan FranzenDokumen4 halamanMy Father's Brain, Jonathan Franzenaryabird100% (1)

- The Sung Dynasty and Its Enemies.: by Chris PeersDokumen9 halamanThe Sung Dynasty and Its Enemies.: by Chris PeersKadathnzBelum ada peringkat

- Dwarven Glory - Core RulesDokumen1 halamanDwarven Glory - Core RulesK-SlackerBelum ada peringkat

- PF2 Sinclairs Almanac v0.9 3o8ww7 - 1 - 4Dokumen140 halamanPF2 Sinclairs Almanac v0.9 3o8ww7 - 1 - 4Sir. ZanetteBelum ada peringkat

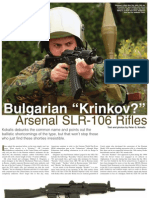

- KrinkovDokumen6 halamanKrinkovliber45Belum ada peringkat

- English MattersDokumen3 halamanEnglish MattersMaya MarchesaBelum ada peringkat