1 s2.0 S1574626713000852 Main

Diunggah oleh

Bryan PrasetyoJudul Asli

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

1 s2.0 S1574626713000852 Main

Diunggah oleh

Bryan PrasetyoHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Australasian Emergency Nursing Journal (2013) 16, 136143

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com

ScienceDirect

journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/aenj

RESEARCH PAPER

Nurse initiated reinsertion of nasogastric tubes in the Emergency Department: A randomised controlled trial

Crystal Hiu Yan Ho, BSc (Hons), MSc, RN a, Timothy Hudson Rainer, MD a,b Colin Alexander Graham, MD, MPH a,b

a b

Trauma & Emergency Center, Accident & Emergency Department, Prince of Wales Hospital, Hong Kong Accident & Emergency Medicine Academic Unit, Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

Received 22 June 2013 ; received in revised form 30 August 2013; accepted 31 August 2013

KEYWORDS

Enteral nutrition; Emergency service, hospital; Emergency nursing; Nurse practitioner; Professional autonomy; Randomised controlled trial

Summary Background: Patients sometimes present to the Emergency Department (ED) for reinsertion of nasogastric tubes (NGT) because of tube dislodgement. They usually need to wait for a long time to see a doctor before the NGT can be reinserted. This study aimed at investigating the feasibility of nurse initiated NGT insertion for these patients in order to improve patient outcome. Methods: This is a prospective randomised controlled trial. Patients requiring NGT reinsertion were randomised to receive treatment by either nurse initiated reinsertion of NGT (NIRNGT) or the standard NGT insertion protocol. Questionnaires were given to both groups of patients, relatives and ED nurses afterwards. Outcome measures included door-to-treatment time, total length of stay (LoS) in the ED and the satisfaction of patients, relatives and nurses. Results: Twenty-two patients were recruited to the study and randomised: 12 in the standard NGT insertion protocol and 10 in the NIRNGT protocol. The door-to-treatment time of the NIRNGT group (mean = 45.6 min) was signicantly shorter than the standard NGT insertion group (mean = 123.08 min; p = 0.003). No statistically signicant difference was detected between the total ED LoS (p = 0.575). Patients, relatives and nurses were generally satised with the new treatment protocol. Conclusion: Patients can undergo NGT reinsertion signicantly faster by adopting a nurse initiated reinsertion of NGT (NIRNGT) protocol. 2013 College of Emergency Nursing Australasia Ltd. Published by Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Corresponding author at: Trauma & Emergency Center, Accident & Emergency Department, Prince of Wales Hospital, New Territories, Hong Kong. Tel.: +852 93133012; fax: +852 26324513. E-mail address: chococrystal@gmail.com (C.H.Y. Ho).

1574-6267/$ see front matter 2013 College of Emergency Nursing Australasia Ltd. Published by Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.aenj.2013.08.005

Can NG tube reinsertion be faster in the ED?

137 While the responsibility for NGT insertion lies mainly with nurses18 and nurse initiated care like NGT insertion is done independently in the ward setting19 and community settings, it is standard practice in the ED at PWH to wait until the patient has been seen by a doctor and the order to reinsert the NGT has been given. We wondered whether nurse initiated reinsertion of the NGT (NIRNGT) in the ED would be feasible to improve the effectiveness of our service and improve patient care for this vulnerable group. The independent role of nursing care has been shown to be effective as demonstrated by the increasing trend of nurse practitioners in emergency care settings20 and the positive outcomes of reductions in waiting time and length of stay in the ED.21

What is known?

Patients presenting to Emergency Department for nasogastric tube reinsertion are commonly seen and they usually need to wait for a long time to see a doctor before getting the tube reinserted. The long waiting time of nasogastric tube reinsertion in Emergency Department correlates with poor patient outcomes. While nurses initiate nasogastric tube reinsertion in ward and community settings, the author query about the possibilities to initiate nasogastric tube reinsertion in Emergency Department.

What this paper adds?

Nurses initiated reinsertion of nasogastric tube in Emergency Department is highly recommended to put into practice as patient could benet and autonomy of nurses increased. In view of the advocacy of nurse practitioner worldwide, new nursing initiatives are encouraged and nurses are able to take up the role independently under the guidance of departmental protocol.

Review of NGT insertion procedure

A nasogastric tube is a tube inserted through the nose into stomach. All registered nurses are trained to perform this procedure independently. The placement of the NGT is rstly checked by testing gastric aspirate with pH indicator strips.18,19,22 Radiography is used to conrm the position whenever there is any doubt.18,23 In the ED of Prince of Wales Hospital, doctors will order NGT insertion and/or subsequent X-ray in writing after seeing the patient. Nurses will then insert the NGT with a placement check. The aim of this study was to investigate the possibility of shortening the waiting time to improve the effectiveness of the ED service by trialling nurse initiated reinsertion of nasogastric tubes (NGT) for long-term enteral feeding patients presenting to the ED.

Introduction

Home enteral nutrition is becoming more common1,2 and nasogastric tubes (NGT) are one of the commonly used routes for enteral feeding. The most common indications for home enteral feeding include chronic neurological problems (usually stroke) and cancer.35 Despite much evidence proving the safety of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG)6 (another type of enteral feeding), many community dwelling adults with swallowing difculties still have a NGT inserted for enteral nutrition. Although there are no local statistics available to indicate the actual population requiring home enteral feeding, it appears that more patients are requiring enteral feeding as mortality from stroke and cancer falls progressively. Long-term enteral feeding patients are usually taken care of by community nurses.3 However, sometimes they present to the Emergency Department (ED) for reinsertion of the NGT when community nurses are not available, especially during non-ofce hours, as feeding is a basic need for the patient, although a short period of fasting is unlikely to be life threatening. In Prince of Wales Hospital (PWH), both the average door-to-treatment time for NGT reinsertion and the average length of stay in the ED overall are very prolonged, as these patients are a relatively low priority as they do not have an immediate threat to life. Long waiting times not only correlate with patients dissatisfaction7 and crowding,8 but also cause conicts between patients and health care professionals which may lead to a higher chance of workplace violence.912 The potential risks of acquiring infection in the ED13 and pressure sore development within hours14 are very relevant for these patients. Poor patient outcomes,8,10,15,16 increased costs16 and poor ED efciency8,17 are likely to result.

Methods

Design

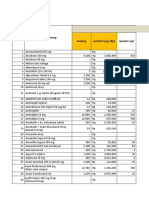

The study was a prospective randomised controlled clinical trial comparing the effectiveness and waiting time of nurse initiated reinsertion of NGT (NIRNGT) and traditional doctor prescribed reinsertion of NGT in patients presenting to the ED. A owchart of the study designed is presented in Fig. 1.

Setting

This study was conducted in the Emergency Department of Prince of Wales Hospital (PWH) in Shatin. It is a 1400-bed university teaching hospital in the New Territories of Hong Kong and is the regional trauma centre. The ED serves a population of approximately 1.5 million and has an annual census of about 150,000 new patients, with 30% admission rate. There are approximately 68 patients visiting the ED per month requiring reinsertion of NG tube because of tube dislodgement.

Patients

All patients older than 18 years old presenting to the ED with dislodgement of NGT requesting reinsertion or requiring a tube placement check during designated periods from 1 October 2009 to 28 February 2010 were considered for study enrolment. Patients with acute variceal bleeding or basal skull fracture19,24 within one week were excluded. Patients

138

C.H.Y. Ho et al.

Figure 1

Flowchart of the study design.

with oesophageal carcinoma or nasopharyngeal carcinoma, patients with vomiting, fever, tachypnea or other signs of pulmonary complication of NGT feeding, and patients in an unstable clinical condition were also excluded. Patients requiring Entriex reinsertion were excluded as Entriex is not routinely inserted by nurses in Hong Kong. Entriex is a small-bore feeding tube with a metal stylet to facilitate passage. During insertion, if the tube is blindly advanced to the airway or the lung, the stylet provides enough rigidity to perforate the lung and cause pneumothorax.22 In addition, a single patient will be included once.

treatment by either nurse initiated reinsertion of NGT (NIRNGT) protocol (intervention group) or standard NGT insertion protocol (control group). It was not possible to blind the patients or the nurses who carried out the intervention. However, we did try to perform single blinding as data entry was completed by the principal investigator who was not involved in the clinical interventions.

Interventions

In the intervention group (NIRNGT protocol), the nurse would reinsert the NGT before the patient was seen by the medical ofcer. Placement was conrmed by aspiration of gastric content with pH 5.18 The nurse would initiate a check chest X-ray for the patient whenever placement was in doubt. The patient then awaited the medical ofcers assessment for discharge. In the control group (standard NGT insertion protocol), the patient would be in the standard queue for the medical ofcers assessment. The ED nurse would then reinsert the NGT after medical ofcers written

Randomisation

Patients were allocated with a random-number generated by computer. The random allocation sequence was implemented with numbered sealed envelopes so that the sequence was concealed until interventions were assigned. The triage nurse would obtain written informed consent before randomisation. All recruited patients would receive

Can NG tube reinsertion be faster in the ED? prescription. The patient then waited for the medical ofcers reassessment before discharge. A short questionnaire was completed by patients and relatives after reinsertion of the NGT in both groups. Another short questionnaire was distributed to the ED nurses at the conclusion of the study.

139

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval was obtained from the joint university and local institutional ethical committee. Informed written consent was obtained from each patient or his/her relative (see below) before voluntary participation.

Training of nurses Prior consent

As every nurse in ED performs NGT insertions and more than half of the eligible patients visit the ED out-of-ofce-hours, including weekends and midnights, investigators included all ED nurses on duty. In order to standardise the procedure, a leaet was distributed to all nurses as a treatment guideline. With the support of Emergency Department senior staff, a few brieng sessions were arranged to inform the nurses about the ow of the study and the NGT insertion procedure. By having nurses as investigators instead of having small number of investigators, the generalisability of the study was increased. Most of the patients requiring long term enteral feeding live in local homes for the elderly. When dislodgement of an NGT occurs, they usually present to the ED with an old age home (OAH) staff member who cannot sign the consent form. With the help of the Shatin Community Geriatric Assessment Team (CGAT), the principal investigator visited 19 private OAHs in Shatin. The study was explained to the managers of these homes. The consent forms together with a letter explaining the study were given to the relatives who had family members requiring NGT feeding by the OAH staff on behalf of the principal investigator. The contact number of the principal investigator was printed on the consent form so that the relatives could ask for further explanation if they had any enquiries. Whenever a patient needed to visit the ED for NGT reinsertion, OAH staff would bring the signed consent form to the ED.

Sample size calculation

The current mean door-to-treatment time of standard NGT reinsertion protocol was calculated by retrieving the previous 6 months data; it was 120 min. We assumed NIRNGT could shorten door-to-treatment time by half. Using an effect size of 60 min (half of the current waiting time for NGT reinsertion), we used an online tool (http://department. obg.cuhk.edu.hk/researchsupport/Sample size CompMean Independent.asp) to derive the sample size for this study. Based on the anticipated difference in means between two groups of 60 min and an anticipated standard deviation of 45 min, with a ratio of 1:1 between the two groups, the estimated sample size was 10 in each group in order to detect a signicant difference with an alpha error of 0.05 and power of 80%. In view of the possibility that some patients may not agree to enter the study and others may withdraw, we aimed to recruit an extra 30%, i.e. 13 patients per group.

Data analysis

Data were analysed using SPSS version 17.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). P < 0.05 was considered as statistically signicant. As the time data did not conform to a Gaussian distribution, non-parametric tests were used. Door-to-treatment time and total LoS were analysed using the MannWhitney U test. Demographic data were summarised using means or presented in percentage.

Results

During the study period, 26 patients presented to the ED requiring NG tube reinsertion, of whom one was excluded because of a past history of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. The remaining 25 patients were randomised; three were later excluded because they had entered the study twice. Twelve patients were randomised into the control group (standard NGT reinsertion protocol) and 10 patients were randomised into the intervention group (NIRNGT) (CONSORT diagram, Fig. 2). No patients withdrew from the study. All patients were discharged home and there were no immediate complications in either group. Of the 22 recruited patients, 12 were female and 10 were male with a mean age of 81.7 years. The mean age of the control group and intervention group were 82.8 and 81.5 years respectively. Twelve patients (54.5%) were OAH residents and 10 (45.5%) were living at home. The median door-to-treatment time of the intervention group was 32.5 min (25th percentile 23.8 min, 75th percentile 67.5 min and interquartile range [IQR] 44 min). The median door-to-treatment time of the control group was 111 min (25th percentile 55.8 min, 75th percentile 177.8 min and IQR 122 min) (Fig. 3). There was a signicant

Data collection and outcomes

The principal investigator reviewed the ED records after NGT reinsertion. Data collected included patient characteristics, time of registration, time of NGT insertion and time of ED departure. The primary outcome was the doorto-treatment time of each patient (i.e. waiting time for treatment) of each patient. The secondary outcomes were the total LoS, patients/relatives satisfaction and nurses satisfaction (Questionnaires were shown in appendices 1 and 2). The endpoint of the study was patient discharge from the ED. We used total LoS as a secondary outcome because from the patients perspective, the time staying in ED after treatment was regarded as waiting time and the total time in the ED is a critical variable. Denitions: 1. Door-to-treatment time: from the time of registration to the time of successful NGT insertion. 2. Total LoS: from the time of registration to the time of leaving the ED.

140

C.H.Y. Ho et al.

Figure 2 CONSORT diagram of the study. One subject was excluded before randomisation because of past history of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Three subjects were excluded after randomisation because of entering the study twice.

difference (p = 0.003) between the door-to-treatment times of two groups. The majority of patients in the intervention group (n = 7, 70%) received treatment (nurse initiated reinsertion of NGT) within 2045 min after registration, with ve patients (50%) receiving treatment within 30 min. The remaining three patients (30%) in the intervention group received treatment within 60100 min (Fig. 4). On the other hand, most patients in the control group (n = 9, 75%) received treatment within 50150 min after registration. Two patients (17%) in the control group received treatment within 200 min and one patient who came on a Sunday received treatment within 35 min. However, there was no signicant difference (p = 0.575) between the total LoS of the two groups. The median total LoS of the intervention group and control group were 173.5 min and 174 min respectively, with IQR of 953 min (25th percentile 143 min; 75th percentile 1095.8 min) and 569 min (25th percentile 108 min; 75th percentile 677 min). The longest total LoS in the intervention group was 1317 min (22 h) and 979 min (16 h) in the control group. Of the 22 patients, six had a total LoS of more than 720 min (12 h) and ve of them were OAH residents.

Questionnaires were given to all patients and relatives (n = 22); 12 questionnaires were collected afterwards (response rate 54.5%). Of the 12 respondents, half of them had visited the ED for NGT reinsertion more than once. All of them (n = 12) wanted the service of nurse initiated reinsertion of NG tube (NIRNGT). Of these 12 participants who wanted the service of NIRNGT, 3 of them preferred to see a doctor before NG tube reinsertion at the same time. The remaining 9 respondents did not express a preference to see a doctor before treatment. All respondents (n = 11, 1 participant did not answer this question) thought that NIRNGT could shorten waiting times. Forty questionnaires were given to ED nurses and 30 were collected (response rate 75%). The 30 nurses were divided into 3 subgroups: 22 were registered nurses (RN), 5 were nursing ofcers (NO) and 3 were advanced practice nurses (APN). Average years of clinical experience were 12.8 years, and average years of clinical experience of the 3 subgroups (APN, NO and RN) were 18.3 years, 24.6 years and 9.4 years respectively. Overall, the nurses were comfortable in performing NIRNGT (26 out of 30 strongly agree or agree). Three participants (3 RN) did not agree that they were comfortable to

Figure 3 groups.

Box plot showing door-to-treatment time of both Figure 4 Box plot showing total LoS of both groups.

Can NG tube reinsertion be faster in the ED? give the treatment before medical ofcers assessment and 1 participant was neutral. Seven nurses (2 APN, 5 RN) strongly agreed and 19 nurses (5 NO, 1 APN, 13 RN) agreed (87%, n = 26) that they were comfortable to carry out this procedure, while 1 RN was neutral. Twenty-eight participants (93%) strongly agreed or agreed (1 did not answer and 1 neutral) that NIRNGT could increase the autonomy of nurses and all nurses believed that NIRNGT could shorten waiting times for the patients.

141 dissatisfaction, crowding, conicts between patients and health care professionals, higher chances of workplace violence, increased costs and poor professional ED efcacy are caused.717 On the contrary, a short waiting time to have treatment is a great benet for patients because nutrition can be resumed as quickly as possible. From a nursing perspective, maintaining a patients hydration and nutrition is our concern and responsibility. Therefore, the authors believe that nurse initiated reinsertion of NG tubes should become routine clinical practice. This is also supported by patients, relatives and nurses on the basis of the questionnaire done in the study. In Hong Kong, nurses do not usually do extended procedures independently. This new initiative of treatment by nurses also parallels the increasing worldwide trend of introducing nurse practitioners to emergency care settings.20,25,28 Because of the increasing demand, workload and working hours of medical residents,29 nurse practitioners are not only rising in number,25 but also expanding and becoming more and more important in the healthcare system.28 The role and function of nursing has ushered in a new era,30,31 and it is now recognised that the nurse is a knowledgeable professional and appropriately skilled to perform many roles that were traditionally performed by doctors.30 In our questionnaire of nurses satisfaction, 87% of the ED nurses felt comfortable to carry out the procedure before medical ofcers assessment and 93% of the nurses strongly agreed or agreed that this initiative of treatment could increase autonomy. Autonomy is a vital ingredient for professionalism and an essential element for full recognition.32 It also plays a fundamental role for emergency nurse practitioners (ENP).28 Autonomy in practice has a positive relationship between nurses job satisfaction, working environment, nurse retention and quality of care.28,33 Feedback from patients and relatives also provided support for this nurse treatment initiative. All participants stated they would like to receive nurse initiated care and all of them believed that waiting times could be shortened. Not only is the nursing perspective changing, the patients perspective is changing too. Patients are accepting nurse initiated care and nurse practitioners more than expected. A study carried out in this ED in 200734 showed that many (59.3%) younger patients (<65 years old) would rather choose an ENP for treatment if the waiting time for a medical ofcers consultation was longer. A similar study from the US showed that the majority (65%) of patients were willing to be seen by an ENP.29 Patients were even more satised with the treatment provided by ENPs than with that from junior doctors.25 Although we believe that NIRNGT is worth implementing, 70% of ED nurses thought that difculties exist because of external factors. The very busy environment may be one of the reasons contributing to the hesitation of the nurses. However, any new initiative in clinical practice is challenging as people are generally fearful of change. According to the three-stage unfreezing, moving and freezing model of change theorised by Lewin,35 some external forces might be needed for these steps. Encouragement from managers and senior staff, group discussions and continuous evaluation may facilitate the change process. The nursing role could

Discussion

This is the rst prospective clinical randomised controlled study evaluating the effectiveness of a nurse initiated procedure for patients who visit the ED requiring reinsertion of NGT in Hong Kong. Our results revealed that the door-totreatment time in the NIRNGT protocol was much shorter than traditional NGT insertion protocol, i.e. patients could get NG tube reinserted faster in NIRNGT protocol. However, both groups stayed equally long in the ED as there was no signicant difference in total LoS. In the NIRNGT protocol, the mean door-to-treatment time was 45.6 min and the mean total LoS was 472.6 min. The waiting time for the Non Emergency Ambulance Transport Service (NEATS) accounted for the long total LoS in both groups. Six patients went home using NEATS, and ve of these patients had a total LoS of more than 12 h. Three patients who were in the NIRNGT protocol had a door-totreatment time within 30 min but a total LoS more than 1000 min (>16 h) because of the wait for the NEATS service. Patients who were waiting for the NEATS service for transport to their homes often needed to wait overnight as they usually came during the out-of-ofce hour period, and the NEATS service was unavailable. Although they were usually relatively clinically stable, having to care for these patients in the ED increases the workload of the health care professionals. Bedside care and basic needs like vital signs monitoring, NG tube feeding and napkin changing are usually provided. It represents a further burden on the busy ED in addition to the large number of attendances, resuscitations and access block patients. To avoid patients waiting in the ED overnight for NEATS, the NEATS service hours could be extended. In our study, 11 patients (50%) registered from 1630 h to 1900 h; if the NEATS service hours were extended to 2100 h, all these patients could be discharged if the NIRNGT protocol was followed. Written information could be given to the OAHs advising them not to bring these patients to the ED during out-ofofce hours unless they can manage to transfer them back after treatment. In our study, there were patients with a total LoS of >1000 min a prolonged wait for NEATS to get back home; these three cases were all in the intervention group. This may account for the lack of signicance in the difference in total LoS between the intervention group and control group. A very signicant difference was detected (p = 0.003) in the door-to-treatment time between the two groups. It is well known that waiting times in all Emergency Departments have been rising for many years.25,26 The long waiting time not only impedes individual access to ED care,27 but also leads to negative outcomes. Poor patient outcomes, patients

142 then evolve and the effectiveness of the service could be improved.

C.H.Y. Ho et al. public, commercial, or not-for-prot sectors. This paper was not commissioned.

Study limitations Acknowledgements

One limitation of this study was the small sample size, with only 22 subjects recruited in the study. There is no similar study in the literature available for reference. The comparatively small sample size was due to the limited data collection time. It is possible that some eligible subjects may have been missed because of external factors like the busy ED environment or the non-availability of a written consent form. However, the small sample size can be justied by its ability to detect a signicant difference in the study. Also, the cognitive state of the patient may affect the outcome as the insertion procedure might be easier for co-operative patients. In addition, the study was conducted in a single centre, which may limit the generalisability of the results. Our questionnaires had not been validated prior to use, which is not ideal, but we believe they have face validity. The response rates for the relatives questionnaire could have been better but the low response rate probably reects the reality of long patient waiting times and the desire to leave the ED as soon as treatment is complete and transport is available. We thank Mr. Stones Wong, Departmental Operational Manager, Miss. Celestina Luk and Miss. Chan Yee Ming, Ward Managers of the Emergency Department at the Prince of Wales Hospital for their full support to carry out the study. We also thank the nursing staff of the Emergency Department at Prince of Wales Hospital for their great help as investigators and for data collection despite the very busy working environment. We thank the Shatin Community Geriatric Assessment Team (CGAT) for their help in obtaining prior consent. We also thank Miss. Josephine Chung, Nurse Consultant in the Emergency Department at Prince of Wales Hospital for her help and valuable opinion for the study.

Appendix 1. Short questionnaire on patients/relatives satisfaction

Questionnaire on patients/relatives satisfaction of nurse initiating reinsertion of NGT in the Emergency Department. Date: Please circle either Yes or No for each question. 1. Is this your rst time coming/accompanying someone to the Emergency Department with dislodged NG tube?

Yes No

Conclusion

This study demonstrated a shorter waiting time for patients receiving treatment by nurse initiated reinsertion of NGT. Although the total time for the patient stay in the ED was the same for both the nurse initiated treatment protocol or traditional NG tube reinsertion protocol, this new initiative was still worthwhile putting into practice. It was supported by the patients/relatives and nurse satisfaction questionnaire, and the increasing scope of practice of emergency nurses. The quality of care, effectiveness of clinical services and the autonomy of the nurse could be improved by this initiative. Future research on a larger scale in Hong Kong and in other countries could conrm our ndings and encourage other emergency providers to set up similar services to improve patient care.

2. Do you want a service of nurse initiating reinsertion of NG tube in the Emergency Department before a doctors assessment?

Yes No

3. Do you prefer a doctors assessment before reinsertion of NG tube?

Yes No

4. Do you think that the waiting time will be shortened if nurses reinsert NG tube before doctors assessment?

Human research ethics approval

Ethical approval was obtained from the joint university and local institutional ethical committee (Joint Chinese University of Hong Kong New Territories East Cluster Clinical Research Ethics Committee) CRE-2009.295-T.

Yes No

Appendix 2. Short questionnaire on nurses satisfaction

Questionnaire on nurses feedback of nurse initiating reinsertion of NGT in the Emergency Department.

Date: Rank: Year of clinical experience:

Funding

This study received no specic grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-prot sectors.

Provenance and conicts of interest

We are unaware of any conict of interest, and the study received no specic grant from any funding agency in the

Please put a in the appropriate box below.

A = Agree SD = Strongly disagree N = Neutral

SA = Strongly agree D = Disagree

Can NG tube reinsertion be faster in the ED?

SA 1. 2. 3. 4. I am comfortable to carry out the procedure (reinsertion of NG tube) before medical ofcers assessment. I think this procedure (nurse initiating reinsertion of NG tube) increases the autonomy of nurses. I think this procedure can help patient in terms of waiting time and quality of nursing care. I think difculties exist for nurse initiating reinsertion of NG tube because of the external factors, e.g. the busy environment. A N D

143

SD

References

1. McNamara EP, Flood P, Kennedy NP. Home tube feeding: an integrated multidisciplinary approach. J Hum Nutr Diet 2001;14:139. 2. Lubke HJ, Niemann C. Enteral access, enteral formula, route of delivery and monitoring enteral nutrition for long-term therapy. Klinikarzt 2004;33:34652. 3. Madigan SM, ONeill S, Clarke J, LEstrange F, MacAuley DC. Assessing the dietetic needs of different patients groups receiving enteral tube feeding in primary care. J Hum Nutr Diet 2002;25:17984. 4. Lloyd DA, Powell-Tuck J. Articial nutrition: principles and practice of enteral feeding. Clin Colon Rectal Surg 2004;17:10718. 5. Jones BJM. 399 Dementia and home enteral tube feeding in the UK: the reality of current practice. Gut 2005;55:A103. 6. Gomes Jr CAR, Lustosa SAS, Matos D, Andriolo RB, Waisberg DR, Waisberg J. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy versus nasogastric tube feeding for adults with swallowing disturbances. Cochrane Database Syst Rev [Internet] 2012 [cited 2013 May 16] http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/14651858. CD008096.pub3/Abstract 7. Goodacre S, Webster A. Who waits longest in the emergency department and who leaves without being seen. Emerg Med J 2005;22:936. 8. Rondeau KV, Francescutti LH. Emergency department overcrowding: the impact of resource scarcity on physician job satisfaction. J Health Care Manag 2005;50:32740. 9. Crilly J, Chaboyer W, Creedy D. Violence towards emergency department nurses by patient. Accid Emerg Nurs 2004;12:6773. 10. Lau JBC, Magarey J, McCutcheon H. Violence in the emergency department: a literature review. Australas Emerg Nurs J 2004;7:2737. 11. Ray MM. The dark side of the job: violence in the emergency department. J Emerg Nurs 2007;33:25761. 12. Whelan T. The escalating trend of violence toward nurses. J Emerg Nurs 2008;34:1303. 13. Rothman RE, Irvin CB, Moran GJ, Sauer L, Bradshaw YS, Fry RB, et al. Respiratory hygiene in the emergency department. J Emerg Nurs 2007;33:11934. 14. Clay M. Pressure sore prevention in nursing homes. Nurs Stand 2000;14(44):4552. 15. ACEP Board of Directors. Crwoding. Ann Emerg Med 2006;27:585. 16. Hoot NR, Aronsky D. Systematic review of emergency department crowding: causes, effects, and solutions. Ann Emerg Med 2008;62:126360.

17. Asplin BR, Magid DJ, Rhodes KV, Solberg LI, Lurie N, Camargo CA. A conceptual model of emergency department crowding. Ann Emerg Med 2003;42:17380. 18. Best C. Nasogastric tube insertion in adults who require enteral feeding. Nurs Stand 2007;21(40):3943. 19. Stroud M, Duncan H, Nightingale J. Guidelines for enteral feeding in adult hospital patients. Gut 2003;52(Suppl. VII):vii12. 20. Campo T, McNulty R, Sabatini M, Fitzpatrick J. Nurse practitioners performing procedures with condence and independence in the emergency care setting. Adv Emerg Nurs J 2008;30:15370. 21. Jennings N, OReilly G, Lee G, Cameron P, Free B, Bailey M. Evaluating outcomes of the emergency nurse practitioner role in a major urban emergency department, Melbourne, Australia. J Clin Nurs 2007;17:104450. 22. de Aguilar-Nascimento JE, Kudsk KA. Use of small-bore feeding tubes: successes and failures. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 2007;10:2916. 23. Metheny NA, Meert KL, Clouse RE. Complications related to feeding tube placement. Curr Opin Gastroenterol 2007;23:17882. 24. Best C. Caring for the patient with a nasogastric tube. Nurs Stand 2005;20(3):5965. 25. Cooper MA, Lindsay GM, Kinn S, Swann IJ. Evaluating emergency nurse practitioner services: a randomized controlled trial. J Adv Nurs 2002;40:72130. 26. Munro J, Mason S, Nicholl J. Effectiveness of measures to reduce emergency department waiting times: a natural experiment. Emerg Med J 2006;23:359. 27. Kennedy J, Rhodes K, Walls CA, Asplin BR. Access to emergency care: restricted by long waiting times and cost and coverage concerns. Ann Emerg Med 2004;43:56773. 28. Bahadori A, Fitzpatrick JJ. Level of autonomy of primary care nurse practitioners. J Am Acad Nurse Pract 2009;21:5139. 29. Hart L, Mirabella J. A patient survey on emergency department use of nurse practitioners. Adv Emerg Nurs J 2009;31:22835. 30. Jones S, Davies K. The extended role of the nurse: the United Kingdom perspective. Int J Nurs Pract 1999;5:1848. 31. Higgins A. The developing role of the consultant nurse. Nurs Manage 2003;10(1):228. 32. Cullen C. Autonomy and the nurse practitioner. Nurs Stand 2000;14(21):536. 33. Kramer M, Maguire P, Schmalenberg CE. Excellence through evidence. J Nurs Adm 2006;36:47991. 34. Ong YS, Tsang YL, Ho YH, Ho FKL, Law WP, Graham CA, et al. Nurses treating patients in the emergency department. A patient survey, Hong Kong. J Emerg Med 2007;14:105. 35. Lewin K. Frontiers in group dynamics. In: Catwright D, editor. Field theory in social science. London: Tavistock Publications; 1959.

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- Helping Adolescents To Better Support Their Peers With A Mental Health Problem: A Cluster-Randomised Crossover Trial of Teen Mental Health First AidDokumen14 halamanHelping Adolescents To Better Support Their Peers With A Mental Health Problem: A Cluster-Randomised Crossover Trial of Teen Mental Health First AidBryan PrasetyoBelum ada peringkat

- A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomised Controlled Trials of Peer Support For People With Severe Mental IllnessDokumen12 halamanA Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomised Controlled Trials of Peer Support For People With Severe Mental IllnessBryan PrasetyoBelum ada peringkat

- Shirley Bach, Alec Grant Communication and Interpersonal Skills For Nurses Transforming Nursing Practice PDFDokumen192 halamanShirley Bach, Alec Grant Communication and Interpersonal Skills For Nurses Transforming Nursing Practice PDFdkekxkxssjxjsjBelum ada peringkat

- GGDokumen64 halamanGGBryan PrasetyoBelum ada peringkat

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (588)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5795)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (345)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (400)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (74)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (266)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1091)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)

- Hepatitis B in PregnancyDokumen46 halamanHepatitis B in Pregnancycitra dewiBelum ada peringkat

- Format BaruDokumen500 halamanFormat BarugunawanBelum ada peringkat

- History of Abnormal BehaviourDokumen31 halamanHistory of Abnormal BehaviourAbdul NazarBelum ada peringkat

- The Learning Curve in Revision Cholesteatoma Surgery: Milan StankovicDokumen7 halamanThe Learning Curve in Revision Cholesteatoma Surgery: Milan StankovicLia BirinkBelum ada peringkat

- PalenD Bsn2 Nutrition Task2Dokumen2 halamanPalenD Bsn2 Nutrition Task2PALEN, DONNA GRACE B.Belum ada peringkat

- Ra-114510 Criminologist Tuguegarao 6-2022Dokumen146 halamanRa-114510 Criminologist Tuguegarao 6-2022G2-Peter Paul PacionBelum ada peringkat

- Historical Evolution of N.researchDokumen26 halamanHistorical Evolution of N.researchAnju Margaret100% (1)

- 2020 Case Report Internasional Short Bowel Sindrom Dan BblserDokumen6 halaman2020 Case Report Internasional Short Bowel Sindrom Dan Bblserdayu mankBelum ada peringkat

- Motivational InterviewingDokumen10 halamanMotivational Interviewingcionescu_7Belum ada peringkat

- Nursing AuditDokumen26 halamanNursing AuditKapil VermaBelum ada peringkat

- GDR Labs™ Androcyn™ +Dokumen7 halamanGDR Labs™ Androcyn™ +juanmelendezusaBelum ada peringkat

- C Ovid 19 Positive Test Report FormDokumen2 halamanC Ovid 19 Positive Test Report FormMinaketan DasBelum ada peringkat

- Sahara Family FlyerDokumen2 halamanSahara Family FlyerGhulam MurtazaBelum ada peringkat

- Waiters Teaching New Parents PDFDokumen1 halamanWaiters Teaching New Parents PDFmp1757Belum ada peringkat

- Clinical Communication Task ScenariosDokumen5 halamanClinical Communication Task ScenariosHadiaDurraniBelum ada peringkat

- Dental AssistantDokumen5 halamanDental Assistantapi-305339646Belum ada peringkat

- Decision Study SorafenibDokumen10 halamanDecision Study SorafenibmiguelalmenarezBelum ada peringkat

- Analisis Sistem Penyelenggaraan Rekam Medis Di Unit Rekam Medis Puskesmas Kota Wilayah Utara Kota KediriDokumen7 halamanAnalisis Sistem Penyelenggaraan Rekam Medis Di Unit Rekam Medis Puskesmas Kota Wilayah Utara Kota Kedirikiki naniBelum ada peringkat

- CBT Exam QuestionDokumen68 halamanCBT Exam Questiondianne ignacioBelum ada peringkat

- AKD - Historical Development of KINESIOLOGYDokumen19 halamanAKD - Historical Development of KINESIOLOGYIda Tiks100% (1)

- M. KOOYMAN The Therapeutic Community and The Medical Model PDFDokumen12 halamanM. KOOYMAN The Therapeutic Community and The Medical Model PDFLagusBelum ada peringkat

- Geriatrics Reflective PaperDokumen7 halamanGeriatrics Reflective PaperRebekah Roberts100% (3)

- This Is LeanDokumen141 halamanThis Is LeanRicardo Adrian Federico100% (5)

- OmanDokumen133 halamanOmandprosenjitBelum ada peringkat

- V3 Medical Providers List Sep 2020 Jeddah&RiyadhDokumen16 halamanV3 Medical Providers List Sep 2020 Jeddah&RiyadhcardossoBelum ada peringkat

- Proposed Rule: TRICARE: Outpatient Hospital Prospective Payment System (OPPS)Dokumen19 halamanProposed Rule: TRICARE: Outpatient Hospital Prospective Payment System (OPPS)Justia.com100% (1)

- Notice: GR Modifier UseDokumen2 halamanNotice: GR Modifier UseJustia.comBelum ada peringkat

- Dabur India LTD Minor ProjectDokumen27 halamanDabur India LTD Minor Projectabhishek tyagiBelum ada peringkat

- OccupationDokumen15 halamanOccupationapi-300148801Belum ada peringkat

- Volunteering and Health: What Impact Does It Really Have?Dokumen101 halamanVolunteering and Health: What Impact Does It Really Have?NCVOBelum ada peringkat