Swanncassonepatagoniapairpaper

Diunggah oleh

api-2306788760 penilaian0% menganggap dokumen ini bermanfaat (0 suara)

45 tayangan11 halamanJudul Asli

swanncassonepatagoniapairpaper

Hak Cipta

© © All Rights Reserved

Format Tersedia

DOCX, PDF, TXT atau baca online dari Scribd

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

© All Rights Reserved

Format Tersedia

Unduh sebagai DOCX, PDF, TXT atau baca online dari Scribd

0 penilaian0% menganggap dokumen ini bermanfaat (0 suara)

45 tayangan11 halamanSwanncassonepatagoniapairpaper

Diunggah oleh

api-230678876Hak Cipta:

© All Rights Reserved

Format Tersedia

Unduh sebagai DOCX, PDF, TXT atau baca online dari Scribd

Anda di halaman 1dari 11

Swann & Cassone On Patagonia MSOD 617

Strategonia: A Pair Paper

Natalie Swann & Marco Cassone

September 25, 2013

Pepperdine University

Dr Chris Worley

MSOD 617 Foundations of Large Systems

Swann & Cassone On Patagonia MSOD 617

The Power of Metaphor in Identity

In Morgans Images of Organization, the reader learns the value of metaphor as a tool

for understanding organizations. The author points out the importance of knowing what a given

metaphor lets one see and what it does not. Metaphor is also useful in defining organization

identity: the relatively enduring metaphor that explains long-term effectiveness and inspires

the organization. (Worley Agility series). This paper affirms the power of identity, addressing

what Patagonias dirtbag metaphor lets the company see and do, and more critically, what it

does not. If we consider that all organizations are perfectly designed to get the results they

get,

(Hanna) this paper will also study the consistent effect the founders values have had on

Patagonias futuring capabilities, its strategy, and its organization design. Recommendations

for Chouinard will follow. As a loose construct for our thinking, we start with and continually

address both sides of the deeply entrenched metaphor that is Patagonias identity.

The Dirtbags of Patagonia, Inc.

As stated in Management Reset, Identity flows from the values that define an

organizations culture and mission (Lawler & Worley, 2011). From the start, Patagonias

overarching directive has been uncompromising integrity around environmentalism, social

change, community, and superior products. Defined through these commitments, the company

is made of like-minded talent that understands and serves a core group of users known as

dirtbags (patagonia.com): consumers who prefer, the human scale to the corporate,

vagabonding to tourism, the quirky and lively to the toned down and flattened out. Eschewing

corporate values and concern for the competition, Yvon Chouinard guides the predominantly

internal focus: At Patagonia, making a profit is not the goal because the Zen master would

say profits happen 'when you do everything else right'. (Chouinard, 2005). Patagonias zen-like

and intransigent inner gaze served it well in many ways, namely in clear core values and

unwavering mission. When it comes to scanning the external environment, however,

Chouinards recycled plastic sports goggles leave him nearsighted at best.

On Futuring at Patagonia

Sustainably managed organizations (SMOs) have a different relationship to risk than

traditional command and control organizations (CCOs) because their economic logic is founded

on change and adaptation rather than stability and control. More important than achieving long-

Swann & Cassone On Patagonia MSOD 617

term competitive advantage, SMOs practice and can be said to be defined by their agility, a

dynamic capability that allows them to perceive internal and external changes and to capitalize

on a series of momentary advantages in a sustainable way.

Regarding social and environmental causes, Patagonia carries the SMO sustainability

banner like no other. Taken from our HBR case study (Reinhardt, Casadesus-Masanell, &

Freier, 2004), heres what Chouinard might highlight as Patagonias sustainable effectiveness:

Aggressively innovative, gathering product feedback from world-class ambassador

athletes (greater surface area), maintaining a lab to develop and test fabrics, and

spending $150,000 on in-the-field testing (double the spending of competitors) (p. 7);

Ambivalent about growth, limiting expansion to 2-4 retail stores per year;

Life-cycle analysis to understand & reduce environmental impact of each product;

Beyond innovation, cautious growth, and care for the planet, a core distinction of SMOs

is their more dynamic relationship to changethey continually scan for internal and external

developments that inform how they view and reconfigure their own resources in order to create

value. This happens through a sophisticated futuring process envisioning potential scenarios

across short-, medium-, and long-term horizons. Broadening our definition of environment to

include competitors, the market, and an increasingly uncertain world, Chouinards lack of

concern for much of anything outside his perspective has produced a tunnel vision that

ultimately undermines Patagonias potential SMO agility:

We tend not to look outside in terms of matching competitors: we compete against

ourselves (lack of dynamic relationship to the environment) (Arneson);

If Patagonia chases a fad, then we lose credibility (missing momentary advantages);

...Americans depend on the outdoors for healthy lifestyles and will always spend

money and time on outdoor pursuits (unaware of future business assumptions) (p. 2);

Single contractors instead of dual sourcing (lack of contingency or scenario planning);

We dont listen to the voice of millions. We listen to the voice of a few dirtbags (p. 3).

To be an agile SMO takes more than a lofty mission serving people, planet, and profit. It

takes a change-friendly identity in which the capacity for ongoing adaptation is embedded in

the DNA of the organization. This is not to suggest neverending change for changes sake;

Patagonia is simply not set up to see, think about, or take advantage of internal or external

changes that are incongruent with its dirtbag metaphor. This inattentional blindness has

unfortunately kept their futuring capabilities underdeveloped with much room for improvement.

Swann & Cassone On Patagonia MSOD 617

Patagonia Strategy What Would Dirtbags Do?

Patagonias indelible identity sources both great strength and unintended constrain.

High on his peak with banner in hand, reluctant businessman Chouinard may approach key

business decisions like his product developers designa you-know-it-when-you-see-it

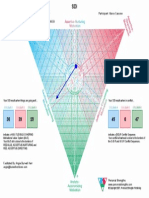

approach (p. 4). Depicted below is a visual representation of PTG strategy (read bottom up):

Strategy can be understood as the interrelated fusion of identity and strategic intent. An

interesting way to think of these is the being and doing of an organization: identity endures, yet

profoundly informs choice of next action. This is why a strong culture such at Patagonias may

resist strategy change and diminish responsiveness to developments in the marketplace.

Pervasive throughout the visual above is a clear Who we are and What we value, the

inward facing elements of identity (culture and mission). Guided by the principles at its peak

Swann & Cassone On Patagonia MSOD 617

(integrity, authenticity, and transparency), it makes sense that Patagonias outward facing

elements (brand and reputation) are virtually a one-to-one match:

Committed to the Core with products backed by an Ironclad Guarantee;

No franchising; all retail stores owned by PTG in order to control product presentation;

Create the best-quality stuff with the least amount of harm to the environment.

Strategic Intent (Minus the Intention Part)

Regarding dimensions of strategic intent, the HBR case study on Patagonia does

portray aspects of breadth, aggressiveness, and differentiation. More often than not, however,

these serve a fixed PTG identity more than they position the company for momentary strategic

advantage:

Product lines twice as broad as competitors, yet limited to one global product line;

More invested in systems (interrelated complementary products) than single products;

Development of a complete product line took twice as long as other specialists;

Two seasonal lines per year vs 4-5 lines produced by most sportswear companies;

50% non-selling space in catalog vs 90%-95% selling space by competitors (p. 11);

A fundamental point of differentiation for Patagonia is that it has a larger purpose than

that of simply making profits. This is what separates Patagonia from its competitors and

inspires loyalty to the brand (Arneson).

As defined in Management Reset, strategic intent is a flexible, momentary strategic

advantage that describes a way to win in the marketplace... built on ...a hit-and-run and entry-

and-exit logic that is responsive to changes in the business environment. Chouinards logic,

however, is more informed by what his inward gaze allows him to see, which often prevents

Patagonia from embracing and capitalizing on change in the external environment:

Products originally made for friends and family; suspicious view of marketing;

Four distinct sales channels treated equally and thought of as a single brand presence;

We always think in terms of our reputation before entering a new market. Are we able

to grow into a new market in such a way that wont compromise our integrity.

In this regard, Patagonia may tout sustainability throughout its identity, however it lacks

the nimble agility of a true SMO. Its economic logic is founded on involvement and commitment

more like a high-involvement organization (HIO), which paradoxically renders the organization

more change-resistant and less sustainable in the long run.

Swann & Cassone On Patagonia MSOD 617

Organization Design, Alignment, and

Sustainable Effectiveness

In this next section, we will review Patagonias organization design and its alignment

through the lens of Galbraiths Star Model (2002). We will conclude this section by commenting

on Patagonias implementation of sustainability into its organization design.

Strategy - Patagonias strategy is driven by the core values and passion for the

environment of its founder. Patagonias mission is to make the best quality, authentic and

innovative high-end outdoor apparel for a niche market, and not screw up the environment

even more in the process. The company differentiates itself from other outdoor apparel brands

by remaining committed to environmentalism, serving as a catalyst for social change, improving

the communities they impact, and to the quality of their products. Patagonia designs with their

core customer in mind: the dirtbag appreciates athletic endeavor for its own sake rather than

for the joy of conquering other competitors or nature (p 3). The sources of Patagonias

competitive advantage boil down to its founders reputation, the brands authenticity and

integrity to its values, customer and employee loyalty, and its dynamic capabilities in design

and production. Patagonias intentional choice of slow growth, lack of debt and minimal

marketing, and unwillingness to pursue fads or chase new non-core customers all speak to

the its desire for sustainable growth and the entrenchment of the founders values and mission

in the companys strategy.

Structure Patagonia is one of six brands under the corporate umbrella, Lost Arrow.

The decision to remain a privately held corporation allows the Patagonia brand to be run in

alignment with its values and to meet the needs of its strategic intent. The current functional

structure, as outlined in the organization chart, appears to support the need to control quality,

Swann & Cassone On Patagonia MSOD 617

monitor the integrity of sales channels, and provide enough fluidity in the structure to make

changes to products based on feedback solicited from Patagonias loyal customers, product

ambassadors, dealer networks, and wholesalers to ensure they are continuously learning and

improving. Overall their structure appears to support their narrow focus and high level of control

over quality. However, to support future growth and sustainability, they may need to consider

how they will organize more collaborative teams within the organization to keep fresh ideas

percolating and prevent departmentalization from keeping the focus too narrow.

Processes Patagonias strategy has a strong impact on their structure and processes.

Their commitment to product quality and aesthetics, innovation, and to limiting their impact on

the environment result in highly dynamic, highly interdependent manufacturing processes that

often include only one supplier of raw materials or one manufacturer of finished goods. Overall

Patagonia seems to run a tight ship and makes solid use of its core resources. The sales

design makes use of wholesalers and dealer networks thus reducing the cost of a sales staff.

The internal staff illustrated on the organization chart appears to meet the current demands of

the core processes performed in house, combined with outsourcing and their collaborative

approach to innovation and problem solving appears to serve them well, making up for their

limitation of resources and conserving labor costs. Although Patagonia's employs a

collaborative approach to product innovation and continuous improvement, their reliance on

long-term relationships instead of formal contracts and choice to often source key inputs (raw

materials) and key production resources (garment sewing) to sole suppliers could negatively

impact their sustainability. If one process, one input (e.g. cotton) or one supplier fails to meet

the intended quality, cost, or time criteria, the entire process and / or output is potentially

disastrously compromised. They could literally miss an entire season of sales.

Swann & Cassone On Patagonia MSOD 617

Rewards - Patagonias rewards reflect their understanding of and commitment to the

people who are motivated by the Companys values. They employ a mixture of recognition,

monetary and intrinsic rewards to maintain a culture of excellence and a strong sense of

community. For example, the company provides speakers series imparting brain food to

employees, provides paid time off to participate in environmental endeavors, their bonus pool is

tied to achievement of the organizations goals, creating a one-for-all community, rather than

just individual recognition. Patagonias employees also enjoy the reward of working for a

company in which they can take a great deal of pride. This is a company that not only promises

high ideals and integrity, they actually walk the talk. Although these choices appear to be

costly they align nicely with a sustainability outlook and will continually help the company attract

and retain the right kind of employees.

People The overarching theme of Patagonias culture is respect for people and the

environment. Patagonias HR policies (may not even be explicit) demonstrate their

commitment managing the organization like an SMO: respecting and promoting work-life

balance, encouraging flexibility in schedules (surfs up!), ensuring healthy and affordable food

on site, higher wages than the industry average; highly subsidized on-site childcare, matching

401(k), and transparency into organizations financial health. Their willingness to oust leaders

and employees who do not share the Companys values is a testament to the importance of

their commitment to sustainability and authenticity. It is unquestionably less costly and more

efficient to pay to retain loyal employees, however, one of the areas the company appears to

pay little attention to is succession planning and training. Although this may only be a factor the

article did not cover, these OD Consultants would question if a sustainable plan is in place to

ensure the company can attract the right people into the C-suite or various key roles over time.

Swann & Cassone On Patagonia MSOD 617

Alignment Overall Patagonias organization design appears to support their strategy

and the environment, although there is room for change and improvement. In alignment with

their strategy, theyve maintained a small core staff, enlisted the support of collaborative

mechanisms, and limited their growth to ensure they can deliver on their promises of quality,

innovation, environmental and financially responsibility. There appears to be enough

governance in the system to control the key inputs into its environment as well as the controls

necessary to ensure the brand identity is protected. The technology and processes appear to

support their ability to fulfill the planned production, maintaining their commitment to quality and

innovation. What is unknown is whether the product mix is too broad to remain dedicated to the

core customer. Although the reward systems and HR elements are aligned to the strategy and

values, it would be of value to investigate the reasons behind the previously high turnover in

the C-Suite, 20% layoffs in 1991, and a Iot of management teams that did not understand what

were about...the values here are so deep (p. 1). Also, is there room for more innovation in the

work systems in which cross-training and various idea teams could be adding value?

Sustainable Effectiveness Overall Patagonia has implemented certain aspects of an

SMO and may be better served in the future by becoming more agile. Their identity, purpose

and environmental commitment support, doing well and doing good over the long run. (Lawler

& Worley, p. 58). Internally, it actively supports sustainable effectiveness values throughout its

culture, encouraging and rewarding employees to do the same. Externally, Patagonia makes a

clear brand promise of sustainable effectiveness and responds consistently to external

stakeholder feedback about its behavior. However, their steadfast desire to remain committed

to one type of customer, one supplier, one type of employee, one way of climbing the mountain

of growth could potentially threaten their ability to address the reality of todays new normal:

faster and faster change, global workforce diversity, and technological advancements.

Swann & Cassone On Patagonia MSOD 617

What Should Chouinard Do?

Recommendations for Patagonia depend on the outcome intended. To build a company

to last 100 years, Chouinard must recognize where his dirtbag perspective helps and where it

hurts Patagonias sustainability: If you want to understand the entrepreneur, study the juvenile

delinquent. The delinquent is saying with his actions This sucks. I'm going to do my own thing.

SMOs cannot ignore or have a counter dependent relationship to the changing, uncertain world.

Chouinard could also lessen his provincial leadership: When I feel like were getting too

numbers-driven or fashion-driven, that we are drifting away from the core, then I step in (p. 4).

Outwardly, Patagonia must grow its ability to perceive, make sense of, and be more

responsive to the outside environment. It must explore what it doesnt know and put structures

in place to allow for external focus. Inwardly, Patagonia must get better at playing with the

future. Internal and external change should inform strategic intent, and futuring across

medium- and long-term horizons will let the organization rethink and reconfigure resources to

create new value. Through scenario planning, Patagonia can better grasp how its

environmental stance might affect financial performance under different strategy alternatives.

The biggest issue for Patagonia is that its designed to appeal to a fixed psychographic

target market that is aging and less active. A higher price point and less-fashion-conscious

design are significant barriers to younger generations; Patagonia has little appeal to Millennials

and is failing to grow a future consumer base (Klebahn). It must expand its target market.

Patagonias innovation appears to be too collapsed into catering to its mature business

rather than taking on new business and expanding the market. The company should aim

creativity at anticipating the needs of the next generation of consumer, including how to reach

them in an updated and more relevant way. Appealing to youth via Patagonias commitments to

social change and community building could be promising. Chouinards suspicion of marketing

needs to go; improving social media presence is a must, as is a more fashionable aesthetic.

It is hard to say whether small victories would be more effective than a sweeping

redesign. Developing the agility to capitalize on momentary competitive advantages will require

enough of a cultural overhaul to diminish resistance to strategy change. Reshaping Patagonias

culture, however, would require a systemic rethinking of organization design. Employees need

to be rewarded for changing, not for becoming lifetimers. More diversity in shareholders would

also support less myopic and zen-like governance. Ultimately, Patagonia does not need to

change its core values much as aspects of its deeply entrenched dirtbag metaphor.

Swann & Cassone On Patagonia MSOD 617

References

Chouinard, Y. Let My People Go Surfing: The Education of a Reluctant Businessman

Galbraith, J. (2002). Designing Organizations. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Hanna, D. Website quote. Retrieved on September 20, 2013 from: http://dave-hanna.net/

Lawler, E. and C. Worley. (2011). Management Reset. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Reinhardt, F., R. Casadesus-Masanell, and D. Freier. (2003). Patagonia. Cambridge, MA:

Harvard Business School Press, 9-703-035.

Worley, C. Organization Design Through an Agility Lens Module 2: The Dynamics of a

Change-friendly Strategy, Pepperdine University.

www.Patagonia.com. Retrieved on January 6, 2003.

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- Cassone Transformative Listening Thesis 7-24-14Dokumen101 halamanCassone Transformative Listening Thesis 7-24-14api-230678876Belum ada peringkat

- Six Degree AlchemyDokumen14 halamanSix Degree Alchemyapi-230678876Belum ada peringkat

- Fab 4 I D e A ObservationsDokumen1 halamanFab 4 I D e A Observationsapi-230678876Belum ada peringkat

- Post-American World For AlchemyDokumen9 halamanPost-American World For Alchemyapi-230678876Belum ada peringkat

- Cassone Learning Journal Summary March 2014Dokumen3 halamanCassone Learning Journal Summary March 2014api-230678876Belum ada peringkat

- Msod620 Blue Team Paper FinalDokumen17 halamanMsod620 Blue Team Paper Finalapi-230678876Belum ada peringkat

- Xcassone Reflection Paper Msod 620Dokumen5 halamanXcassone Reflection Paper Msod 620api-230678876Belum ada peringkat

- Cassone 616 Individual Learning JournalDokumen5 halamanCassone 616 Individual Learning Journalapi-230678876Belum ada peringkat

- Marcos Shortened Profile For AlchemyDokumen11 halamanMarcos Shortened Profile For Alchemyapi-230678876Belum ada peringkat

- Sdi Interpretive GuideDokumen7 halamanSdi Interpretive Guideapi-230678876Belum ada peringkat

- Book Summary Notes Post American World FinalDokumen4 halamanBook Summary Notes Post American World Finalapi-230678876Belum ada peringkat

- Cassone M Admissions EssayDokumen1 halamanCassone M Admissions Essayapi-230678876Belum ada peringkat

- Marco Cassone 60b29a1c 5f80 4f24 Ad08 6344215913a7Dokumen1 halamanMarco Cassone 60b29a1c 5f80 4f24 Ad08 6344215913a7api-230678876Belum ada peringkat

- Marcos PDC Oct 2013Dokumen1 halamanMarcos PDC Oct 2013api-230678876Belum ada peringkat

- Ocai Omicron Prime Culture Report Ver 6Dokumen9 halamanOcai Omicron Prime Culture Report Ver 6api-230678876Belum ada peringkat

- MGT Reset 10 TakeawaysDokumen14 halamanMGT Reset 10 Takeawaysapi-230678876Belum ada peringkat

- Palleschi RecommendationDokumen1 halamanPalleschi Recommendationapi-230678876Belum ada peringkat

- Ai Alchemy SlidedeckDokumen25 halamanAi Alchemy Slidedeckapi-230678876Belum ada peringkat

- Ai in Practice Imagining A Bright Future ChesleyDokumen47 halamanAi in Practice Imagining A Bright Future Chesleyapi-230678876Belum ada peringkat

- Cassone Learning Journal SummaryDokumen2 halamanCassone Learning Journal Summaryapi-230678876Belum ada peringkat

- Cassone Complexity in Di InitiativesDokumen9 halamanCassone Complexity in Di Initiativesapi-230678876Belum ada peringkat

- Cassone Reflection Paper Msod 620Dokumen5 halamanCassone Reflection Paper Msod 620api-230678876Belum ada peringkat

- Closing Session PosterDokumen1 halamanClosing Session Posterapi-230678876Belum ada peringkat

- Complexity Alchemy PresentationDokumen42 halamanComplexity Alchemy Presentationapi-230678876Belum ada peringkat

- Marco Final Exam Study Prep2Dokumen26 halamanMarco Final Exam Study Prep2api-230678876Belum ada peringkat

- Cassone Ppov Paper 621Dokumen4 halamanCassone Ppov Paper 621api-230678876Belum ada peringkat

- Cassone 616 Post-Session Emlyon Evaluation PaperDokumen6 halamanCassone 616 Post-Session Emlyon Evaluation Paperapi-230678876Belum ada peringkat

- Diversity & Inclusion DiscussionDokumen9 halamanDiversity & Inclusion Discussionapi-230678876Belum ada peringkat

- Msod620 Cango Pres FinalDokumen85 halamanMsod620 Cango Pres Finalapi-230678876Belum ada peringkat

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5794)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (344)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (587)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (73)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (265)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)

- Data Classification Using Support Vector Machine: Durgesh K. Srivastava, Lekha BhambhuDokumen7 halamanData Classification Using Support Vector Machine: Durgesh K. Srivastava, Lekha BhambhuMaha LakshmiBelum ada peringkat

- FET - Faculty List MRIU Updated 12.6.17 - ParthasarathiDokumen55 halamanFET - Faculty List MRIU Updated 12.6.17 - Parthasarathiபார்த்தசாரதி சுப்ரமணியன்Belum ada peringkat

- HemeDokumen9 halamanHemeCadenzaBelum ada peringkat

- The Horace Mann Record: Delegations Win Best With Model PerformancesDokumen8 halamanThe Horace Mann Record: Delegations Win Best With Model PerformancesJeff BargBelum ada peringkat

- MobileMapper Office 4.6.2 - Release NoteDokumen5 halamanMobileMapper Office 4.6.2 - Release NoteNaikiai TsntsakBelum ada peringkat

- W5 - Rational and Irrational NumbersDokumen2 halamanW5 - Rational and Irrational Numbersjahnavi poddarBelum ada peringkat

- Math 221 AssignmentsDokumen25 halamanMath 221 AssignmentsSiddhant SharmaBelum ada peringkat

- PR1Dokumen74 halamanPR1Danna Mae H. PeñaBelum ada peringkat

- 6 Bền cơ học ISO 2006-1-2009Dokumen18 halaman6 Bền cơ học ISO 2006-1-2009HIEU HOANG DINHBelum ada peringkat

- Mario Tamitles Coloma JR.: POSITION DESIRE: Structural Welder/S.M.A.W/F.C.A.W ObjectivesDokumen3 halamanMario Tamitles Coloma JR.: POSITION DESIRE: Structural Welder/S.M.A.W/F.C.A.W ObjectivesJune Kenneth MarivelesBelum ada peringkat

- Distributed Flow Routing: Venkatesh Merwade, Center For Research in Water ResourcesDokumen20 halamanDistributed Flow Routing: Venkatesh Merwade, Center For Research in Water Resourceszarakkhan masoodBelum ada peringkat

- Kim Mirasol Resume Updated 15octDokumen1 halamanKim Mirasol Resume Updated 15octKim Alexis MirasolBelum ada peringkat

- PT 2 Pracba1Dokumen2 halamanPT 2 Pracba1LORNA GUIWANBelum ada peringkat

- Final Examination: Print DateDokumen1 halamanFinal Examination: Print Datemanish khadkaBelum ada peringkat

- Aep Lesson Plan 3 ClassmateDokumen7 halamanAep Lesson Plan 3 Classmateapi-453997044Belum ada peringkat

- Educational Base For Incorporated Engineer Registration - A22Dokumen5 halamanEducational Base For Incorporated Engineer Registration - A22Prince Eugene ScottBelum ada peringkat

- Reading AdvocacyDokumen1 halamanReading AdvocacySamantha Jean PerezBelum ada peringkat

- LESSON PLAN EnglishDokumen7 halamanLESSON PLAN EnglishMarie Antonette Aco BarbaBelum ada peringkat

- Disciplines and Ideas in The Applied Social SciencesDokumen21 halamanDisciplines and Ideas in The Applied Social SciencesPhillip Matthew GamboaBelum ada peringkat

- LS-DYNA Manual Vol2Dokumen18 halamanLS-DYNA Manual Vol2Mahmud Sharif SazidyBelum ada peringkat

- Aho - Indexed GrammarsDokumen25 halamanAho - Indexed GrammarsgizliiiiBelum ada peringkat

- 4 Simple Ways to Wake Up EarlyDokumen8 halaman4 Simple Ways to Wake Up EarlykbkkrBelum ada peringkat

- Nihilism's Challenge to Meaning and ValuesDokumen2 halamanNihilism's Challenge to Meaning and ValuesancorsaBelum ada peringkat

- 2017 - 01 Jan GVI Fiji Caqalai Hub Achievement Report Dive Against Debris & Beach CleansDokumen2 halaman2017 - 01 Jan GVI Fiji Caqalai Hub Achievement Report Dive Against Debris & Beach CleansGlobal Vision International FijiBelum ada peringkat

- In Text CitationsDokumen9 halamanIn Text CitationsRey Allyson MartinezBelum ada peringkat

- Science Report For Coins RotationDokumen2 halamanScience Report For Coins Rotationapi-253395143Belum ada peringkat

- Additional C QuestionsDokumen41 halamanAdditional C Questionsvarikuti kalyaniBelum ada peringkat

- Strain Index Calculator English UnitsDokumen1 halamanStrain Index Calculator English UnitsFrancisco Vicent PachecoBelum ada peringkat

- Dr. NTR UHS PG Medical Admission Guidelines 2017Dokumen34 halamanDr. NTR UHS PG Medical Admission Guidelines 2017vaibhavBelum ada peringkat

- A Post Colonial Critical History of Heart of DarknessDokumen7 halamanA Post Colonial Critical History of Heart of DarknessGuido JablonowskyBelum ada peringkat