Pi Is 1051044308004739

Diunggah oleh

ardian_primaJudul Asli

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Pi Is 1051044308004739

Diunggah oleh

ardian_primaHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

WrongProcedure, WrongPerson Surgerytothe

Practiceof InterventionalRadiology

are conceptualized by the Safety and

ature databases. Then a critical review

Standards of Practice

Quality Improvement Guidelines for Preventing

Wrong Site, Wrong Procedure, and Wrong Person

Errors: Application of the Joint Commission

Universal Protocol for Preventing Wrong Site,

John F. Angle, MD, Albert A. Nemcek, Jr, MD, Alan M. Cohen, MD, Donald L. Miller, MD,

Clement J. Grassi, MD, Horacio R. DAgostino, MD, Arshad Ahmed Khan, MD, Sanjoy Kundu, MD,

Robert B. Osnis, MD, Dheeraj K. Rajan, MD, Marc S. Schwartzberg, MD, Timothy L. Swan, MD,

Suresh Vedantham, MD, Michael J. Wallace, MD, and John F. Cardella, MD, for the SIR Standards Division

J Vasc Interv Radiol 20081;9:11451151

Abbreviation: WS wrong site

PREAMBLE

represent a valid broad expert constitu-

METHODOLOGY

ency of the subject matter under consid-

THE membership of the Society of In-

eration for standards

production.

SIR produces its Standards of Prac-

terventional Radiology (SIR) Standards

Technical documents specifying the

tice documents using the following

of Practice Committee represents ex-

exact consensus and literature review

process. Standards documents of rele-

perts in a broad spectrum of interven-

vance and timeliness are conceptual-

tional procedures from both the private

methodologies as well as the institu-

ized by the Standards of Practice Com-

and academic sectors of medicine. Gen-

tional afliations and professional cre-

mittee members. Certain documents

erally, Standards of Practice Committee

dentials of the authors of this docu-

members dedicate the vast majority of

ment are available upon request from

Health Committee. A recognized ex-

their professional time to performing in-

SIR, 3975 Fair Ridge Dr., Suite 400,

pert is identifed to serve as the prin-

terventional procedures; as such they Fairfax, VA 22033.

From the Department of Radiology (J.F.A.), Univer- of Vascular of Interventional Radiology (D.R.), De-

cipal author for the standard. Addi-

tional authors may be assigned

dependent upon the magnitude of the

project.

An in-depth literature search is per-

sity of Virginia Health System, Charlottesville, Vir- partment of Medical Imaging, University of Toron-

formed using electronic medical liter-

ginia; Department of Radiology (A.A.N.), North- to/University Health Network, Toronto, Ontario,

western Memorial Hospital, Chicago, Illinois; Canada; RADIA (R.B.O.), Everett, Washington; Ra-

Department of Vascular and Interventional Radiol- diology Associates of Central Florida (M.S.S.), Lees-

ogy (A.M.C.), University of TexasHouston; Depart- burg, Florida; Department of Radiology (T.L.S.),

ment of Interventional Radiology (M.J.W.), The Uni- Marshfeld Clinic, Marshfeld, Wisconsin; and

versity of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center,Mallinckrodt Institute of Radiology (S.V.), Washing-

Houston, Texas; Department of Radiology (D.L.M.), ton University School of Medicine, St. Louis,

Uniformed Services University, Bethesda, Mary- Missouri. Received March 6, 2008; fnal revision re-

land; Department of Radiology (C.J.G.), Boston ceived and accepted March 19, 2008. Address cor-

Healthcare System/Veterans Afairs Medical Cen- respondence to J.F.A., c/o SIR, 3975 Fair Ridge

ter, Boston; Department of Radiology (J.F.C.), Bay- Drive, Suite 400 North, Fairfax, VA 22033;

state Health System, Springfeld, Massachusetts; De- E-mail: jfa3h@virginia.edu

partment of Radiology (H.A.D.), Louisiana State

University Health Sciences Center, Shreveport, Lou-

None of the authors have identifed a confict of

isiana; Department of Interventional Radiology

interest.

(A.A.K.), Washington Hospital, Bethesda, Mary-

SIR, 2008

land; Department of Medical Imaging (S.K.), Scar-

borough General Hospital, Richmond Hill; Division DOI: 10.1016/j.jvir.2008.03.027

of peer-reviewed articles is performed

with regards to the study methodol-

ogy, results, and conclusions. Ordi-

narily, the qualitative weight of these

articles is assembled into an evidence

table, which is used to write the doc-

ument such that it contains evidence-

based data with respect to content,

rates, and thresholds. However, an ev-

idence table is not relevant to this

guideline

When the evidence of literature is

weak, conficting, or contradictory, con-

1145

122 QI Guidelines to Prevent Wrong Site/Procedure/Person Errors

August 2008 JVIR

sensus for the parameter is reached by

a minimum of 12 Standards of Practice

Committee members using a Modifed

Delphi Consensus Method (Appendix

A) (1,2). For purposes of these docu-

ments consensus is defned as 80% Del-

phi participant agreement on a value or

parameter.

The draft document is critically re-

viewed by Safety and Health Commit-

tee members and then by Standards of

Practice Committee members, either

by telephone conference calling or

face-to-face meeting. The fnalized

draft from the Standards of Practice

Committee is sent to the SIR member-

ship for further input/criticism

during a 30-day comment period.

These com- ments are discussed by the

Standards of Practice Committee, and

appropri- ate revisions made to create

the fn- ished standards document.

Prior to its publication the document is

endorsed by the SIR Executive

Council.

INTRODUCTION

The purpose of this document is

to provide guidelines for a safe, ac-

curate, and consistent process for

verifying the interventional proce-

dural treatment site. This material is

intended as a supplement to the ex-

isting Joint Commission guideline,

Universal Protocol for Preventing

Wrong Site, Wrong Procedure, Wrong

Person Surgery (referred heretofore

as the Universal Protocol), adopted by

the Joint Commission on July 18, 2003,

and subsequently updated (3) . This

document is available at http://www.

jointcommission.org/PatientSafety /

UniversalProtocol/. The contents of this

document are intended to assist inter-

ventional radiologists in developing a

standard operating procedure for clin-

ical application of the Joint Commis-

sion guideline.

Preventing wrong site, wrong proce-

dure, and wrong person surgery errors

requires a reliable system of procuring

clinical information/prior imaging,

pro- cedure planning, and

dissemination of information. The Joint

Commission re- fers to this process as

the preoperative verifcation process

(3). Several fea- tures unique to

interventional radiology will be

discussed later in this report.

The Joint Commission document

defnes preoperative skin marking as a

step in the process of preventing

wrong site (WS) errors (3). Skin mark-

ing is necessary for only a limited

number of the procedures interven-

tional radiologists perform, because

for most interventional radiology pro-

cedures, (i) side is irrelevant for the

procedure or (ii) imaging guidance is

an inherent part of the procedure. This

document attempts to delineate the

process for determining those proce-

dures for which site marking is re-

quired.

Prevention of WS errors should be

part of a patient identifcation system

that also prevents wrong person and

wrong procedure errors. Active com-

munication and collaboration are

expected among all perioperative/

procedural team members. This com-

munication and collaboration must

also include the patient. The process

should culminate in a team discussion

in the procedure room immediately

before the start the procedure. This

step is referred to as the time out (3).

Even if a procedure is exempt from the

requirement for skin marking, the re-

mainder of the time out process must

still be performed as outlined in the

Universal Protocol. This policy may

not apply in emergent, life-threatening

clinical situations at the discretion of

the responsible physician.

Interventional radiology imaging

equipment can lead to left/right er-

rors. The interventional radiologist is

also responsible for making certain

that images are correctly labeled be-

fore being sent to a Picture Archiving

and Communication System or other

permanent storage medium in order

to prevent future WS errors.

DEFINITIONS

The following defnitions are taken

verbatim from the Joint Commission

Web site.

Marking the Operative Site

Marking the site is required for

procedures involving right/left dis-

tinction, multiple structures (such as

fngers and toes), or levels (as in spinal

procedures). Site marking is not re-

quired (nor is it prohibited) for other

procedures. These may include mid-

line sternotomy, Cesarean section, lap-

arotomy and laparoscopy, cardiac

catheterization and other interven-

tional procedures for which the site of

insertion is not predetermined. For

those procedures in which site mark-

ing is not required, the other require-

ments for preventing wrong site,

wrong procedure, wrong person sur-

gery still apply (4).

Time Out

To conduct a fnal verifcation of

the correct patient, procedure, site

and, as applicable, implants. Active

communication among all members of

the surgical/procedure team, consis-

tently initiated by a designated mem-

ber of the team, conducted in a fail-

safe mode, that is, the procedure is

not started until any questions or con-

cerns are resolved (3).

Invasive Procedure

The universal protocol should be

applicable or adaptable to. . . invasive

procedures that expose patients to

harm, including procedures done in

settings other than the operating

room (3). Certain routine minor

procedures such as venipuncture, pe-

ripheral [intravenous catheter] place-

ment, insertion of [nasogastric] tube,

or Foley catheter insertion are not

within the scope of the protocol (4).

Sentinel Event

A sentinel event is an unexpected

occurrence involving death or serious

physical or psychological injury, or the

risk thereof. Serious injury specifcally

includes loss of limb or function. The

phrase, or the risk thereof includes

any process variation for which a re-

currence would carry a signifcant

chance of a serious adverse outcome.

Such events are called sentinel be-

cause they signal the need for imme-

diate investigation and response (3).

UNIVERSAL PROTOCOL

In July 2003, The Joint Commission

Board of Commissioners approved the

Universal Protocol for Preventing

Wrong Site, Wrong Procedure, and

Wrong Person Surgery. The Universal

Protocol was created to address the

continuing occurrence of these tragic

medical errors in Joint Commission ac-

credited organizations. The Universal

Protocol became efective July 1, 2004,

for all accredited hospitals, ambula-

tory care and ofce-based surgery fa-

cilities. The Universal Protocol drew

upon, and expanded and integrated, a

series of requirements under The Joint

Commissions 2003 and 2004 National

Patient Safety Goals. It is applicable to

all operative and other invasive proce-

dures. The principal components of

the Universal Protocol include: (i) the

pre-operative verifcation process; (ii)

marking of the operative site; (iii) tak-

ing a time out immediately before

starting the procedure; and (iv) adap-

tation of the requirements to non op-

erating room settings, including bed-

side procedures (3).

These guidelines are written to be

used in quality improvement pro-

grams to assure all procedures are per-

formed on the correct patient and at

the correct site. The most important

processes for achieving these goals

are planning/evaluation, preproce-

dure marking, and intraprocedural/

time out stages. The outcome mea-

sures or indicators for these processes

are (i) appropriate information ac-

quired to plan appropriate site and

side obtained before the procedure

when possible, (ii) frequency of mark-

ing of site before the procedure when

indicated, (iii) confrming that a time

out occurred, and (iv) incidence of WS

errors. Outcome measures are as-

signed threshold levels at the institu-

tion.

Practicing physicians should strive to

achieve a perfect process (eg, 100%

marking of site when indicated). In

practice all physicians will fall short of

this ideal to a variable extent. When

measures such as indications, or success

rates, fall below a (minimum)

threshold, or when complication rates

exceed a (maximum) threshold, a

review should be performed to

determine causes and to implement

changes, if necessary. Each

institution/hospital should defne

thresholds as needed for the process

steps, defned in detail later in these

guidelines, to meet its own quality im-

provement program needs. Therefore,

indicator thresholds may be used

locally

to assess the efcacy of ongoing quality

improvement programs. For example, if

the incidence of procedures for which a

time out is not performed is one mea-

sure of quality in preventing WS errors,

then values in excess of a threshold

should trigger a review of policies and

procedures within the department to

determine the causes and to implement

changes to lower the incidence of the

missed step.

WS errors are a sentinel event (3),

so the threshold for these events

should be zero and any such events

should be reviewed carefully using

root cause analysis. Individual compli-

cations or a breach in the standard of

practice may also be associated with

the subsequent development of a WS

event (5). Therefore, all such events, as

well as close calls should be subject

to peer review. Patterns of complica-

tions that could lead to a WS error

should be addressed.

Complications can be stratifed on

the basis of outcome. Major complica-

tions result in admission to a hospital

for therapy (for outpatient proce-

dures), an unplanned increase in the

level of care, prolonged hospitaliza-

tion, permanent adverse sequelae, or

death. WS errors involving an invasive

procedure are major complications.

Placement of a central catheter on the

less desirable side is not a major com-

plication unless there are clinical is-

sues indicating one side should be

used. Minor complications result in no

sequelae; they may require nominal

therapy or a short hospital stay for

observation (generally overnight; Ap-

pendix B).

Implementing the Universal

Protocol

The application of the Universal

Protocol for patient identifcation is in-

dicated for all invasive procedures.

(The Joint Commissions specifc ex-

pectations for implementation of the

Universal Protocol are available on

their Web site [6].) Within the group of

procedures subject to the Universal

Protocol are a subset of procedures for

which skin marking is required and a

subset of procedures for which skin

marking is not necessary. This portion

of the guideline attempts to clarify cer-

tain issues that may arise during im-

plementation of the Universal Proto-

col. All quotations in this section are

taken from the Joint Commission Web

site.

Time Out Process

The purpose of the time out is to

conduct a fnal verifcation of the

correct patient, procedure, site and, as

applica- ble, implants (3). The time

out, or immediate preoperative pause,

must oc- cur in the location where the

procedure is to be done (for example,

when the patient is on the operating

table). Given this restriction, the time

out may pre- cede induction of

anesthesia or may oc- cur after the

patient is anesthetized (par- ticipation

by the patient is not expected) but just

before starting the procedure (4). The

time out must involve the entire

surgical team. At a minimum, this

includes active participation by the sur-

geon, anesthesia provider, and circulat-

ing nurse. Participation by the other

members of the team, as appropriate to

their involvement in the procedure, is

also encouraged. In particular, there

should be no barrier to anyone

speaking up if there is concern about a

possible error. To include some

members of the team but not others

sends the wrong message (4).

For interventional radiology, this

means that the time out should be per-

formed after the patient is placed on

the procedure table, regardless of

whether this is in the interventional

fuoroscopy suite, the computed to-

mography (CT) scanner, an ultra-

sound (US) room, or at the bedside.

All personnel involved in the proce-

dure should also be involved in the

time out. The time out must be per-

formed before the invasive procedure

is started.

Procedures for Which the Site/Side

Must Be Marked on the Skin

The correct site must be marked for

all invasive procedures involving (i)

right/left distinction based on

external landmarks, history, or prior

studies; or (ii) multiple structures

(fngers, toes) or levels (spine) (3). If

both the left and right side will be sites

for inter- vention, both must be

marked. For

spine procedures, the general region

may be marked, but the exact level

should be determined with intraproce-

dural imaging (3).

For interventional radiology, the

side or individual structure may be

known, in which case it should be

marked on the skin. Alternatively, the

lesion may be identifed during intra-

procedural imaging, in which case it

cannot be marked on the skin. This

situation would normally be ex-

empted based on the continuous pres-

ence exemption (as described later).

There are situations in which site

marking is required by the Joint Com-

mission, but implementation of this re-

quirement is difcult or impossible.

For example, if angioplasty of the right

renal artery is planned, theoretically

the skin over the right kidney should

be marked. However, after the patient

is draped, this mark will not be visible.

In these situations, the Joint Commis-

sion recommends marking the skin at

or near the proposed incision/inser-

tion site to indicate the correct side of

the proposed procedure, even when

the proposed incision/insertion site is

in the midline or through a natural

body orifce. This mark, as for other

site marks, must be positioned to be

visible after the patient is prepped and

draped unless it is technically or ana-

tomically impossible or impractical to

do so (4). This would require a skin

mark on the groin indicating which

renal artery is to undergo angioplasty.

This is a potential source of confusion

because it may be seen as an indication

of which common femoral artery

should be punctured. The Joint Com-

mission advises that, in such techni-

cally difcult cases, an alternative

method for visually identifying the

correct side should be used (eg, a tem-

porary unique wrist band or other

similar device) (4). Unfortunately,

such an alternative method is unlikely

to be visible through the sterile drapes.

In these cases, the Society of Interven-

tional Radiology recommends that the

side of intervention be confrmed in

the manner traditionally used by inter-

ventional radiologists: appropriate in-

traprocedural imaging. This is consis-

tent with the Joint Commissions

requirement that spinal levels be con-

frmed with imaging at the time of the

intervention.

Situations Excluded from the Skin

Marking Requirement

Site marking is not required (nor is

it prohibited) for procedures other

than those described earlier in this re-

port. These may include mid-line

sternotomy, Cesarean section, laparot-

omy and laparoscopy, cardiac cathe-

terization and other interventional

procedures for which the site of inser-

tion is not predetermined. For those

procedures in which site marking is

not required, the other requirements

for preventing wrong site, wrong pro-

cedure, wrong person surgery still ap-

ply (4).

Situations with right/left distinc-

tion in which intraprocedural imaging

is used to provide confrmation of the

correct side may also be exempt from

the marking requirement. The Joint

Commission requires site marking

when there is right/left distinction

based on external landmarks, history,

or prior studies (emphasis added) (4).

Situations in which right/left distinc-

tion is determined or confrmed with

intraprocedural imaging before the in-

tervention (the case in virtually all in-

terventional procedures) do not fall

within this requirement. This interpre-

tation is consistent with New York

State Surgical and Invasive Procedure

Protocol (exception E7) (7). When both

left- and right-sided structures are

known to be abnormal (eg, bilateral

hydronephrosis), the Society of Inter-

ventional Radiology recommends that

skin marking be performed even if in-

traprocedural imaging is employed.

It is the opinion of the Society of

Interventional Radiology that, in pro-

cedures in which vascular access is

simply a means to provide a route of

access to perform a procedure or to

provide central venous access, skin

marking at the vascular access site is

not needed. This is consistent with the

Joint Commission guidance cited ear-

lier in this report regarding cardiac

catheterization. Placement of central

venous catheters is a special clinical

situation in which side marking is not

required, but in which it is good clin-

ical practice to investigate if there is a

preferred side.

In addition to the exemptions noted

earlier, the Joint Commission specif-

cally notes that skin marking is not

mandatory if the practitioner perform-

ing the procedure remains with the

patient continuously from the time the

decision is made to do the procedure

and consent is obtained from the pa-

tient up to the time of the procedure

itself (3). Finally, the patient always

has the right to refuse skin marking

(4).

Method for Performing Skin

Marking

The Protocol states, The person

performing the procedure should do

the site marking. The word should

is in contrast to the more defnitive

term must, which is used elsewhere

in the Protocol. It recognizes the need

for fexibility to accommodate the lo-

gistical and procedural realities of the

full range of surgical facilities. When it

is not feasible for the person perform-

ing the procedure to mark the site,

another member of the surgical team

who is fully informed about the pa-

tient and the intended procedure must

do the marking. In this context, the

preoperative registered nurse is con-

sidered a member of the surgical team.

Any delegation of responsibility for

marking the surgical site must be con-

sistent with applicable law and regu-

lations (we are advised that some

states may prohibit nurses from mark-

ing the surgical site). The organization

must ensure that whenever the re-

sponsibility for site marking is dele-

gated to someone other than the per-

son who will be doing the procedure,

the safety of the patient will not be

compromised. Note that while the

Protocol requires that the patient be

involved in the process, it is not ex-

pected, or even recommended, that

the patient mark his/her own surgical

site (4).

The [Universal] Protocol does not

specify the type of markthat is left to

the organization to decide but what-

ever the decision on this, the mark

must be unambiguous and the process

should be consistent throughout the

organization. Consideration should be

given to aligning the site marking pro-

cedures with those of other surgical

facilities in the same geographic area,

since surgeons are frequently on mul-

tiple medical stafs. Use of X is dis-

couraged since this may be ambigu-

ous: does X mean operate here or

do not operate here? A line indicat-

ing the intended site of incision, the

surgeons initials, or the word yes are

all preferable ways to mark the site

(4).

A marker that is sufciently per-

manent to remain visible and will not

wash of when the site is prepped may

be used for marking the site (4). Un-

der the Universal Protocol, adhesive

site markers are permitted as an ad-

junct to directly marking the skin.

While the Protocol does not explicitly

prohibit the use of adhesive markers,

it does state, Adhesive site markers

should not be used as the sole means

of marking the site. This means that

when site marking is required, it must

be done by directly marking the skin

(4).

Site marking should be done prior

to moving the patient into the room

where the procedure will be done. Part

of the requirement is that the site

marking be done with the involve-

ment of the patient. For this to be

done in a meaningful way, it should

happen before the patient is signif-

cantly sedated. Participation may be

precluded by a disease state or heavy

sedation. However, sedation by itself

does not necessarily prevent the pa-

tient from participating in the site

marking process. The patients capac-

ity to participate must be based on an

individual assessment (4).

In cases of non-speaking, coma-

tose, or incompetent patients, or chil-

dren, the patient involvement in the

site marking process should be han-

dled in the same way that you handle

the informed consent process. Who-

ever has authority to provide in-

formed consent for the patient to un-

dergo the procedure would, as

appropriate, participate in the site

marking process (4).

Clinical Emergency

None of these precautions should

interfere with the timely care of the

patient in an emergency situation. In

most of these cases, when invasive

procedures are performed under

emergency or urgent conditions, the

practitioner performing the procedure

will be in continuous attendance of the

patient from the point of decision to

do the procedure. Under those circum-

stances, marking the site would not be

necessary, although the time-out to

verify the correct patient, procedure,

and site would still be appropriate

(unless it was such an emergency that

even the time out would add more

risk than beneft) (4).

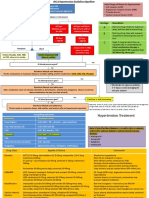

PROCEDURE

The purpose of this Guideline is to

provide an outline for the implemen-

tation of the Universal Protocol for

prevention of WS errors in an inter-

ventional radiology practice. One

must frst be familiar with the expec-

tations for implementation of the Uni-

versal Protocol outlined by the Joint

Commission (6). In addition, there are

several steps in the process that beneft

from elaboration and specifcation in

regards to interventional radiology.

The source of WS errors in interven-

tional radiology can be divided into

planning/evaluation (ie, preprocedure

verifcation), preprocedure marking,

and intraprocedural time-out (3)

stages. The postprocedure stage is also

important to prevent future errors in

the same patient.

Planning/Evaluation

Errors can be caused by omission or

commission. Controlling WS errors at

this stage should focus on preventing

scheduling errors because these can

easily be perpetuated in subsequent

stages (eg, patient is scheduled for a

right nephrostomy when they really

need a left nephrostomy). This plan-

ning/evaluation stage is also impor-

tant in avoiding a missed opportunity

to order outside radiologic studies or

copies of operative reports that may be

helpful in preventing WS errors in

later stages (see 3 below). Informed

consent is often done in advance,

which adds another opportunity for

the patient to participate in the plan-

ning of the procedure. There is sub-

stantial evidence that active early in-

volvement of patients in the planning

of their procedures prevents many WS

errors (8). During the consent process,

the patient and the patients family

should understand that the site of skin

entry and the site of treatment may be

diferent.

If possible, indicate the side and site

at the time of procedure scheduling

(often indicated by a referring physi-

cian) or preprocedural evaluation in

the interventional radiology clinic.

Scheduling should be performed by a

health care professional familiar with

interventional radiology procedures

whenever possible.

Make sure all potentially necessary

images and/or reports are requested

so they are available at the time of

proce- dure. If benefcial, mark or

annotate the region of interest on the

flms/images. Appropriate physician-to-

physician com- munication should be

the norm.

Preprocedural Marking

Preprocedural marking is only

rarely required in interventional radi-

ology procedures. More importantly,

in the immediate preprocedural pe-

riod, information from many diferent

sources should be collected. The inter-

ventional radiologist or designee are

responsible for insuring that the cor-

rect structure and side are identifed

on previous studies. This identifca-

tion process may require marking a

flm (or Picture Archiving and Com-

munication System image) with the in-

tended site of treatment.

Patient marking is necessary only

when direct puncture into the area of

interest is done based on external

landmarks (rather than intraproce-

dural imaging) and there is a possibil-

ity for left/right or level errors (see

Indications section).

Time Out

The time out is fully described on

the Joint Commission Web site (3), but

errors unique to interventional radiol-

ogy can occur when preprocedural in-

formation is not conveyed to the staf

and physicians performing the proce-

dure. For example, a patient with mul-

tiple lesions on a planning magnetic

resonance (MR) angiogram or CT an-

giogram could undergo a diferent

procedure in the absence of appropri-

ate communication.

Intraprocedural errors can also oc-

cur as a result of patient positioning

(prone versus supine) and patient ori-

entation in the room. These errors may

not be immediately recognized by the

interventional radiologist because of

patient draping that masks the anat-

omy. Site marking will prevent this

error, but the time out should include

a review of the patients orientation.

Imaging equipment (eg, fuoros-

copy, US, CT, MR, or other) that does

not insure correct orientation or label-

ing of the images could potentially

lead to errors. The interventional radi-

ologist should be aware of this issue,

and use the time out to confrm corre-

spondence between the image guid-

ance system image and the patient ori-

entation (eg, the apparent left side of

the patient in the image on the screen

corresponds to the patients left side).

Manual entry of patient informa-

tion into the imaging equipment may

lead to misidentifcation of the images

as belonging to the wrong patient. The

time out process should include a step

to confrm that the correct patients

information is displayed on the image

monitor before the procedure is

started.

Postprocedure

Make certain that all permanent im-

ages are correctly labeled regarding

patient and side before archiving. A

regular program of equipment main-

tenance and quality assurance is rec-

ommended.

Success Rates

There is no literature evidence to

determine an acceptable success rate

in executing these steps. Success rates

should approach 100%, but will have

to be locally determined and moni-

tored.

Complications

In 1998, the Joint Commission re-

ceived 15 reports of wrong site, wrong

person, or wrong procedure surgery. In

a Sentinel Event Alert issued in Decem-

ber 2001, 150 such instances were re-

ported, 41% of which were related to

orthopedic or podiatric surgery (9). The

Joint Commission identifed emergency

procedures, unusual physical character-

istics of the patient, time pressures,

mul- tiple surgeons, and multiple

procedures on the same patient as risk

factors. In a survey of orthopedic

surgeons, of an es- timated 6,700,000

surgical procedures,

242 were performed at the wrong site,

for an incidence of one in 27,686 proce-

dures (10). An analysis of insurance

claims and malpractice claims suggest

that the incidence appears to be one in

112,994 for surgery in general (11). It is

recommended that there be a zero

threshold for this type of error and a

quality improvement initiative with

peer review be undertaken when one of

these events is identifed (8).

Estimating the frequency of WS er-

rors in interventional radiology is

essen- tially impossible. Published rates

for in- dividual types of complications

are highly dependent on patient

selection and are based on series

comprising thousand of patients, and

for proce- dures far removed from an

interven- tional radiology practice. No

reliable data exist for interventional

radiology procedures.

Acknowledgment: Dr. John F. Angle au-

thored the frst draft of this document and

served as topic leader during the subse-

quent revisions of the draft. Dr. Donald L.

Miller is chair of the SIR Safety and Health

Committee. Dr. John F. Cardella is Coun-

cilor of the SIR Standards Division. All

other authors are listed alphabetically.

Other members of the Safety and Health

Committee and SIR who participated in

the development of this clinical practice

guide- line are as follows: Stephen Balter,

PhD, Daniel B. Brown, MD, Timothy W.I.

Clark, MD, MSc, Bairbre L. Connolly, MD,

Brian D. Davison, MD, Neil M. Khilnani,

MD, Patrick C. Malloy, MD, J. Kevin

McGraw, MD, Philip M. Meyers, MD,

Steven F. Mill- ward, MD, Charles A.

Owens, MD, Darren Postoak, MD, Dheeraj

K. Rajan, MD, Anne C. Roberts, MD, Steven

C. Rose, MD, Nasir H. Siddiqu, MD, LeAnn

Stokes, MD, Patri- cia E. Thorpe, MD, Louis

K. Wagner, PhD, Bret N. Wiechmann, MD,

Darryl A. Zuck- erman, MD, Curtis W.

Bakal, MD, Curtis A. Lewis, MD, MBA, JD,

Kenneth S. Rholl, MD, David Sacks, MD,

Robert G. Dixon, MD, James R. Duncan,

MD, PhD, Kathleen Gross, RN, George

G. Hartnell, MD, Donald Larsen, MD,

Jorge A. Leon, MD, Neal Naito, MD, MPH,

Anne Oteham, RN, BSN, William Pavlicek,

PhD, Cindy Kaiser Saiter, NP, Beth

Schueler, PhD, John D. Statler, MD, Richard

B. Towbin, MD, Jo- seph A. Ronsivalle, DO,

Michael S. Stecker, MD, Rajeev Suri, MD,

Louis K. Wagner, PhD, and Eric M. Walser,

MD.

APPENDIX A: CONSENSUS

METHODOLOGY

Reported complication-specifc rates

in some cases refect the aggregate of

major and minor complications. Thresh-

olds are derived from critical evaluation

of the literature, evaluation of empirical

data from Standards of Practice Com-

mittee members practices, and, when

available, the SIR HI-IQ System na-

tional database.

Consensus on statements in this

document was obtained utilizing a

modifed Delphi technique. (1,2)

APPENDIX B: SOCIETY OF

INTERVENTIONAL

RADIOLOGY STANDARDS OF

PRACTICE COMMITTEE

CLASSIFICATION OF

COMPLICATIONS BY

OUTCOME

Minor Complications

A. No therapy, no consequence

B. Nominal therapy, no consequence;

includes overnight admission for

observation only.

Major Complications

C. Require therapy, minor hospital-

ization ( 48 hours)

D. Require major therapy, unplanned

increase in level of care, prolonged

hospitalization ( 48 hours).

E. Permanent adverse sequelae

F. Death.

References

1. Fink A, Kosefcof J, Chassin M, Brook

RH. Consensus methods: characteris-

tics and guidelines for use. Am J Public

Health 1984; 74:979 983

2. Leape LL, Hilborne LH, Park RE, et al.

The appropriateness of use of coronary

artery bypass graft surgery in New

York State. JAMA 1993; 269:753760.

3. Joint Commission. Universal Protocol

for Preventing Wrong Site, Wrong Pro-

cedure, Wrong Person Surgery. Avail-

able at http://www.jointcommission.

org/PatientSafety/UniversalProtocol/

.

Accessed March 12, 2007.

4. Joint Commission. Frequently asked ques-

tions about the Universal Protocol for

Preventing Wrong Site, Wrong Proce-

dure, Wrong Person Surgery. Available

at

http://www.jointcommission.org/

PatientSafety/UniversalProtocol/up_

faqs.htm. Accessed March 12, 2007.

5. Wong DR, Vander Salm TJ, Ali IS, Ag-

nihotri AK, Bohmer RM, Torchiana DF.

Prospective assessment of intraopera-

tive precursor events during cardiac

surgery. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2006;

29:447 455.

6. Joint Commission. Implementation

Expectations for the Universal Proto-

col for Preventing Wrong Site, Wrong

Procedur e an d Wron g Perso n

Surgery.

http://www.jointcommission.org/NR

/ rdonlyres/DEC4A816-ED52-4C04-

AF8C-

FEBA74A732EA/0/up_guidelines.pdf

. Accessed March 12, 2007.

7. State of New York Department of

Health. New York State surgical and in-

vasive procedure protocol. September

2006. Availabl e a t http://www.health.

state.ny.us/professionals/protocols_and

_

guidelines/surgical_and_invasive_

procedure/docs/protocol.pdf.

Accessed March 18, 2007

8. Caryon P, Schultz K, Hundt AS.

Righting wrong site surgery. Joint

Comm J Qual Saf 2004; 30:405

410.

9. Canale ST. Wrong-site surgery: a pre-

ventable complication. Clin Orthop Rel

Res 2005; 433:26 29.

10. Meinberg EG, Stern PG. Incidence of

wrong site surgery among hand sur-

geons. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2003; 85:

193197.

11. Kwaan MR, Studdert DM, Zinner MJ,

Gawande AA. Incidence, patterns,

and prevention of wrong-site surgery.

Arch Surg 2006; 141:353357.

The clinical practice guidelines of the Society of Interventional Radiology attempt to defne practice principles that

generally should assist in producing high quality medical care. These guidelines are voluntary and are not rules. A

physician may deviate from these guidelines, as necessitated by the individual patient and available resources. These

practice guidelines should not be deemed inclusive of all proper methods of care or exclusive of other methods of care

that are reasonably directed towards the same result. Other sources of information may be used in conjunction with

these principles to produce a process leading to high quality medical care. The ultimate judgment regarding the

conduct of any specifc procedure or course of management must be made by the physician, who should consider all

circumstances relevant to the individual clinical situation. Adherence to the SIR Quality Improvement Program will

not assure a successful outcome in every situation. It is prudent to document the rationale for any deviation from the

suggested practice guidelines in the department policies and procedure manual or in the patients medical record.

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- A Conceptual Model of Emergency Department CrowdingDokumen2 halamanA Conceptual Model of Emergency Department Crowdingardian_primaBelum ada peringkat

- Medication: PR Ac T Ice Standar DDokumen32 halamanMedication: PR Ac T Ice Standar Dardian_primaBelum ada peringkat

- Emergency Department Crowding: High-Impact Solutions: Acep Task Force Report On BoardingDokumen20 halamanEmergency Department Crowding: High-Impact Solutions: Acep Task Force Report On Boardingardian_primaBelum ada peringkat

- Emp C Crowding PPRDokumen8 halamanEmp C Crowding PPRardian_primaBelum ada peringkat

- A Conceptual Model of Emergency Department CrowdingDokumen2 halamanA Conceptual Model of Emergency Department Crowdingardian_primaBelum ada peringkat

- Read MeDokumen16 halamanRead MeAsad IslamBelum ada peringkat

- Standard of Nursing ServicesDokumen30 halamanStandard of Nursing Servicesardian_primaBelum ada peringkat

- Infection Control Nurses AssociationDokumen43 halamanInfection Control Nurses Associationlelgeorge100% (2)

- Standard of Nursing ServicesDokumen30 halamanStandard of Nursing Servicesardian_primaBelum ada peringkat

- Higher Algebra - Hall & KnightDokumen593 halamanHigher Algebra - Hall & KnightRam Gollamudi100% (2)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (344)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (73)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2259)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (120)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)

- 6 Injury Severity Coding v2Dokumen31 halaman6 Injury Severity Coding v2FaizanBelum ada peringkat

- Kyphosis & LordosisDokumen14 halamanKyphosis & LordosisTrixie Marie Sabile Abdulla100% (3)

- Bethesda 14Dokumen12 halamanBethesda 14BegognaAnguloCruzado100% (1)

- Bab 3Dokumen32 halamanBab 3Ciptaningrum Marisa PBelum ada peringkat

- Assignment and Delegation Guidelines: For Registered Nurses and Licensed Practical NursesDokumen20 halamanAssignment and Delegation Guidelines: For Registered Nurses and Licensed Practical Nursesanna regarBelum ada peringkat

- Peripheral Arterial ExamDokumen2 halamanPeripheral Arterial ExamliyeexzBelum ada peringkat

- Patient Counseling FormDokumen2 halamanPatient Counseling FormMarifuddin Hussaini50% (2)

- The Code of Ethics For NursesDokumen8 halamanThe Code of Ethics For NursesZulkifli PomalangoBelum ada peringkat

- CKD Pocket GuideDokumen2 halamanCKD Pocket GuideLutfi MalefoBelum ada peringkat

- Medical English 170X240Dokumen408 halamanMedical English 170X240Lucia100% (3)

- Fundamentals of Nursing ReviewerDokumen28 halamanFundamentals of Nursing ReviewerJamaica Manuel Iglesias100% (1)

- Alternativas A TotalesDokumen12 halamanAlternativas A TotalesJuan Jose Stuven RodriguezBelum ada peringkat

- What Is Humanistic CounsellingDokumen9 halamanWhat Is Humanistic CounsellingSankalp JainBelum ada peringkat

- MedStart UMAT Sample and Practice QuestionsDokumen55 halamanMedStart UMAT Sample and Practice QuestionsLyn JiangBelum ada peringkat

- Sonography of Normal and Abnormal Thyroid and Parathyroid Glands PDFDokumen15 halamanSonography of Normal and Abnormal Thyroid and Parathyroid Glands PDFJheyson Javier Barrios PereiraBelum ada peringkat

- Care UniteDokumen6 halamanCare UniteAhmad Gamal Elden MAhanyBelum ada peringkat

- Fabry DiseaseDokumen63 halamanFabry DiseaseKunal PaulBelum ada peringkat

- Psych NBME Form 4Dokumen2 halamanPsych NBME Form 4Christine CassidyBelum ada peringkat

- Admission Nursing AssessmentDokumen20 halamanAdmission Nursing Assessmentmonir61Belum ada peringkat

- Listening To and Making Facilitates Brain Recovery ProcessesDokumen2 halamanListening To and Making Facilitates Brain Recovery Processestonylee24Belum ada peringkat

- Lithoskop Product BrochureDokumen20 halamanLithoskop Product BrochureJaseel AkBelum ada peringkat

- Hypersensitivity: Dr. Amit Makkar, Sudha Rustagi Dental CollegeDokumen117 halamanHypersensitivity: Dr. Amit Makkar, Sudha Rustagi Dental Collegeamitscribd1Belum ada peringkat

- Theories - Thesis ProposalDokumen12 halamanTheories - Thesis ProposalJordan Cruz100% (2)

- Adrenal Tumor-Pheochromocytoma 10-10-19Dokumen30 halamanAdrenal Tumor-Pheochromocytoma 10-10-19JessicaBelum ada peringkat

- Truncus ArteriosusDokumen19 halamanTruncus ArteriosusHijaz Al-YamanBelum ada peringkat

- Horizontal Jaw RelationDokumen101 halamanHorizontal Jaw Relationruchika0% (1)

- Ahead Adc MCQDokumen12 halamanAhead Adc MCQSOMVIR KUMARBelum ada peringkat

- Clinical Counselor Outpatient Therapist in Crestview FL Resume Deidre George-MullinsDokumen2 halamanClinical Counselor Outpatient Therapist in Crestview FL Resume Deidre George-MullinsDeidreGeorgeMullinsBelum ada peringkat

- JNC8 HTNDokumen2 halamanJNC8 HTNTaradifaNurInsi0% (1)

- ADR News Dec2008 Vol10 No3Dokumen8 halamanADR News Dec2008 Vol10 No3William ChandraBelum ada peringkat