A Conversation With Elie Wiesel

Diunggah oleh

api-2631384290 penilaian0% menganggap dokumen ini bermanfaat (0 suara)

266 tayangan1 halamanJudul Asli

a conversation with elie wiesel

Hak Cipta

© © All Rights Reserved

Format Tersedia

DOCX, PDF, TXT atau baca online dari Scribd

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

© All Rights Reserved

Format Tersedia

Unduh sebagai DOCX, PDF, TXT atau baca online dari Scribd

0 penilaian0% menganggap dokumen ini bermanfaat (0 suara)

266 tayangan1 halamanA Conversation With Elie Wiesel

Diunggah oleh

api-263138429Hak Cipta:

© All Rights Reserved

Format Tersedia

Unduh sebagai DOCX, PDF, TXT atau baca online dari Scribd

Anda di halaman 1dari 1

English 30-1

Isherwood

A Conversation With Elie Wiesel (Excerpted)

Many of our discussions and journal entries dealt with Elie Wiesels relationship with God

throughout the course of Night. This interview, from Midstreams March/April 2006 feature,

provides some insight into his current beliefs.

Joseph Lowin: When he was eleven years old, my older son, David, took Night off the bookshelf and

read it in one sitting. After finishing the book, he asked me: Is Elie Wiesel still Jewish? When I asked

him, Why? he responded, Because he no longer believes in God. That young boy is now a man.

What can you tell him about your ongoing struggle with belief?

Elie Wiesel: First of all, Jewish? I become more and more Jewish. Whatever I do, I do for my own

people. Whatever I do, I do as a Jew. I believe that I can help others, that I can speak to others, that I

can teach others, and always as a Jew. For me, therefore, it is important to see the whole world through

the eyes of a Jew. I say it again and again. I say it all the time; I choose to identify myself as a Jew. I

acknowledge that a Catholic, a Buddhist, or an atheist has the same right of self-identification.

Joseph Lowin: So you flunked Assimilation 101?

Elie Wiesel: I never even registered for that course. Some writers were seduced, but I was never

tempted. My problem is not with Judaism but with humanity. As to my beliefs, people didnt

understand about my faith [in the camps]. I never lost my faith. If I had lost my faith, I would have

had no problem. I dont say I dont have problems with God. I do have problems with God. As I say

elsewhere, the tragedy of the believer is deeper than the tragedy of the non-believer. The non-believer

has a problem with humanity, not with God. We had both. I did have problems eventually, but not

immediately. I stand by every word in Night. In Night [and in my play, The Trial of God] I say we

condemn God, but immediately afterward we went to prayer. Not only that. We had, in Auschwitz,

somebodya non-Jewwho smuggled in a pair of tefillin for I dont know how many portions of

bread. Every dayevery day[my father and I] we got up and laid tefillin. There was no reason to do

that. It was not one of the three laws of ye-hareg ve-al yaavor [for which one must permit oneself to be

killed and not transgress]. And what is the prayer we said? Ahavah Rabbah Ahavtanu [You have loved

us with abundant love]. What kind of prayer was Ahavah Rabbah? And then we continued, Hemlah

Gedolah Viyteirah Hamalta Aleinu [You have pitied us with exceedingly great pity]. Where is the

Ahavah? Where is the Hemlah? And when I came out of Auschwitz to France, into a childrens home, I

became very, very religious. I really became almost as religious as I was as a child [in Sighet]. What

saved me, what saved my sanity was study [of Jewish texts]. I never stopped learning. Later on, in

the fifties, when I studied philosophy and theology [at the Sorbonne], I began to be invaded by doubts,

all the questions we have now in philosophy and theology, Gods presence in history, Gods action in

history, Gods relationship to his creation. Again, not that I stopped believing in God.

http://www.midstreamthf.com/200603/feature.html

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- Reflections of an Unconverted Convert: Elie Wiesel, the Problem of God, and One Jew’s Return HomeDari EverandReflections of an Unconverted Convert: Elie Wiesel, the Problem of God, and One Jew’s Return HomeBelum ada peringkat

- Elie Wiesel EssayDokumen7 halamanElie Wiesel EssayFazzyPlaxBelum ada peringkat

- Evil and Exile: Revised EditionDari EverandEvil and Exile: Revised EditionPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1)

- Subtitle 5Dokumen10 halamanSubtitle 5JoshBelum ada peringkat

- Research Paper Night Elie WieselDokumen5 halamanResearch Paper Night Elie Wieseltutozew1h1g2Belum ada peringkat

- Five Questions If Youre A Jehovahs Witness by Jacob PraschDokumen19 halamanFive Questions If Youre A Jehovahs Witness by Jacob PraschsirjsslutBelum ada peringkat

- Hell No: The Surprising Truths the Bible Teaches about Death, Resurrection, and JudgmentDari EverandHell No: The Surprising Truths the Bible Teaches about Death, Resurrection, and JudgmentBelum ada peringkat

- Thesis Ideas For Night by Elie WieselDokumen7 halamanThesis Ideas For Night by Elie Wieselbrendawhitejackson100% (2)

- Jewish ChristianityDokumen38 halamanJewish Christianitykaleb16_2Belum ada peringkat

- The Answer: God's Covenants of Promise: What All People Need to KnowDari EverandThe Answer: God's Covenants of Promise: What All People Need to KnowBelum ada peringkat

- Jewish Memory - InfeldDokumen8 halamanJewish Memory - Infeldapi-202630766Belum ada peringkat

- Velvet Elvis Discussion GuideDokumen6 halamanVelvet Elvis Discussion GuideSim KamundeBelum ada peringkat

- Renewed Each Day—Leviticus, Numbers & Deuteronomy: Daily Twelve Step Recovery Meditations Based on the BibleDari EverandRenewed Each Day—Leviticus, Numbers & Deuteronomy: Daily Twelve Step Recovery Meditations Based on the BibleBelum ada peringkat

- Trading Places: Abrar House, 45 Crawford Place, Edgware Road, LondonDokumen4 halamanTrading Places: Abrar House, 45 Crawford Place, Edgware Road, LondonRadical Middle WayBelum ada peringkat

- Elie Wiesel Night Research Paper TopicsDokumen7 halamanElie Wiesel Night Research Paper Topicsaflefvsva100% (1)

- Y’all Have Sinned: How Blaming Others Is Not A Winning StrategyDari EverandY’all Have Sinned: How Blaming Others Is Not A Winning StrategyBelum ada peringkat

- ba2a0c2e6e296375d78257621bb2c7fc9ba6936012b68bf54e32ee247a1ae064Dokumen154 halamanba2a0c2e6e296375d78257621bb2c7fc9ba6936012b68bf54e32ee247a1ae064Eduardo RabassalloBelum ada peringkat

- You Never Step into the Same Pulpit Twice: Preaching from a Perspective of Process TheologyDari EverandYou Never Step into the Same Pulpit Twice: Preaching from a Perspective of Process TheologyBelum ada peringkat

- He Walked With God, He Pleased God, For God Took Him: (Hebrews 11:5)Dokumen4 halamanHe Walked With God, He Pleased God, For God Took Him: (Hebrews 11:5)DanOkirorLo'OlilaBelum ada peringkat

- Night Final Rough DraftDokumen3 halamanNight Final Rough Draftapi-460956371Belum ada peringkat

- Won’t He Do It? God Can Do It Just Like That!Dari EverandWon’t He Do It? God Can Do It Just Like That!Belum ada peringkat

- God in Search of Man KindleDokumen3 halamanGod in Search of Man KindleDodoechBelum ada peringkat

- Enoch Walked With GodDokumen9 halamanEnoch Walked With GodGabriel DincaBelum ada peringkat

- Exam StrategiesDokumen8 halamanExam Strategiesapi-263138429Belum ada peringkat

- Why Does God Seem So Hidden?: A Trinitarian Theological Response to J. L. Schellenberg’s Problem of Divine HiddennessDari EverandWhy Does God Seem So Hidden?: A Trinitarian Theological Response to J. L. Schellenberg’s Problem of Divine HiddennessBelum ada peringkat

- 30-2 Chapter 12 VocabDokumen4 halaman30-2 Chapter 12 Vocabapi-263138429Belum ada peringkat

- The Real Bible Code: Never Been Interested in God Religion or the Bible!Dari EverandThe Real Bible Code: Never Been Interested in God Religion or the Bible!Belum ada peringkat

- Social 20 Courseoutline 20162017Dokumen3 halamanSocial 20 Courseoutline 20162017api-263138429Belum ada peringkat

- Social30 2courseoutline20162017Dokumen3 halamanSocial30 2courseoutline20162017api-263138429Belum ada peringkat

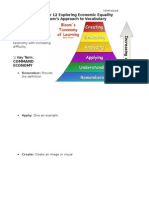

- Understandings of Economic EqualityDokumen3 halamanUnderstandings of Economic Equalityapi-263138429Belum ada peringkat

- Faith that Prevails: Home and Group Questions for TodayDari EverandFaith that Prevails: Home and Group Questions for TodayPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (3)

- Social 20 Final Exam ReviewDokumen4 halamanSocial 20 Final Exam Reviewapi-263138429Belum ada peringkat

- Alden Nowlan and Glass RosesDokumen14 halamanAlden Nowlan and Glass Rosesapi-263138429Belum ada peringkat

- Banana Land Doc HandoutDokumen3 halamanBanana Land Doc Handoutapi-263138429Belum ada peringkat

- Bad Girls and Boys Go to Hell (or not): Engaging Fundamentalist EvangelicalismDari EverandBad Girls and Boys Go to Hell (or not): Engaging Fundamentalist EvangelicalismBelum ada peringkat

- February 2 English 30-2 JournalDokumen1 halamanFebruary 2 English 30-2 Journalapi-263138429Belum ada peringkat

- Approaching God: Accepting the Invitation to Stand in the Presence of GodDari EverandApproaching God: Accepting the Invitation to Stand in the Presence of GodPenilaian: 5 dari 5 bintang5/5 (2)

- Diploma Part A PrepDokumen2 halamanDiploma Part A Prepapi-263138429Belum ada peringkat

- English 10 Course OutlineDokumen3 halamanEnglish 10 Course Outlineapi-263138429Belum ada peringkat

- Chapter 10 Soc 20-2Dokumen2 halamanChapter 10 Soc 20-2api-263138429Belum ada peringkat

- Did God Die on the Way to Houston? A Queer Tale: A Work of Theological FictionDari EverandDid God Die on the Way to Houston? A Queer Tale: A Work of Theological FictionBelum ada peringkat

- English 10 Course OutlineDokumen3 halamanEnglish 10 Course Outlineapi-263138429Belum ada peringkat

- Spiritual Activism: A Jewish Guide to Leadership and Repairing the WorldDari EverandSpiritual Activism: A Jewish Guide to Leadership and Repairing the WorldPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (2)

- "We Rise by Lifting Others.": A Farewell Activity For Social Studies 20Dokumen5 halaman"We Rise by Lifting Others.": A Farewell Activity For Social Studies 20api-263138429Belum ada peringkat

- Chapter 13 30-2 VocabDokumen3 halamanChapter 13 30-2 Vocabapi-263138429Belum ada peringkat

- Connaître Sacral Olo: The Meaning of a Metaphorical Life Companion: the Censored EditionDari EverandConnaître Sacral Olo: The Meaning of a Metaphorical Life Companion: the Censored EditionBelum ada peringkat

- Tou 2060 Blooms VocabularyDokumen3 halamanTou 2060 Blooms Vocabularyapi-263138429Belum ada peringkat

- Touching the Bones of Elisha: Nine Life-Giving Spiritual Practices from an Ancient ProphetDari EverandTouching the Bones of Elisha: Nine Life-Giving Spiritual Practices from an Ancient ProphetBelum ada peringkat

- MosquehatecrimeDokumen2 halamanMosquehatecrimeapi-263138429Belum ada peringkat

- Economic SystemsDokumen2 halamanEconomic Systemsapi-263138429Belum ada peringkat

- The Case for Christ Bible Study Guide Revised Edition: Investigating the Evidence for JesusDari EverandThe Case for Christ Bible Study Guide Revised Edition: Investigating the Evidence for JesusPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (6)

- MosquehatecrimeDokumen2 halamanMosquehatecrimeapi-263138429Belum ada peringkat

- Coming To Jesus: One Man's Search for Truth and Life PurposeDari EverandComing To Jesus: One Man's Search for Truth and Life PurposePenilaian: 5 dari 5 bintang5/5 (1)

- RepbypopDokumen2 halamanRepbypopapi-263138429Belum ada peringkat

- Chapter 11 Party PoliticisDokumen3 halamanChapter 11 Party Politicisapi-263138429Belum ada peringkat

- A Touch of the Sacred: A Theologian's Informal Guide to Jewish BeliefDari EverandA Touch of the Sacred: A Theologian's Informal Guide to Jewish BeliefPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (2)

- Chapter 10soc20-1Dokumen3 halamanChapter 10soc20-1api-263138429Belum ada peringkat

- Unilateralism and The Cold WarDokumen4 halamanUnilateralism and The Cold Warapi-263138429Belum ada peringkat

- Visitor Information CentersDokumen3 halamanVisitor Information Centersapi-263138429Belum ada peringkat

- Breaking the Tablets: Jewish Theology After the ShoahDari EverandBreaking the Tablets: Jewish Theology After the ShoahBelum ada peringkat

- Famine in The Ukraine 1932Dokumen3 halamanFamine in The Ukraine 1932api-263138429Belum ada peringkat

- M C Examreviewsoc30riiiDokumen6 halamanM C Examreviewsoc30riiiapi-263138429Belum ada peringkat

- Social 20-3chp8kettermsDokumen2 halamanSocial 20-3chp8kettermsapi-263138429Belum ada peringkat

- The Forbidden Fruit Or The Forbidden Truth..in The Bible?Dari EverandThe Forbidden Fruit Or The Forbidden Truth..in The Bible?Belum ada peringkat

- Alberta Human RightsDokumen2 halamanAlberta Human Rightsapi-263138429Belum ada peringkat

- Faith Facing Reality: Stirring Up Discussion with BonhoefferDari EverandFaith Facing Reality: Stirring Up Discussion with BonhoefferBelum ada peringkat

- Social 20-1chapter8keytermsDokumen2 halamanSocial 20-1chapter8keytermsapi-263138429Belum ada peringkat

- Unification Insights Into Marriage and Family: The Writings of Dietrich F. SeidelDari EverandUnification Insights Into Marriage and Family: The Writings of Dietrich F. SeidelBelum ada peringkat

- British Empire in IndiaDokumen18 halamanBritish Empire in Indiaapi-263138429Belum ada peringkat

- The Perpetual Novena of Our Lady of Perpetual HelpDokumen12 halamanThe Perpetual Novena of Our Lady of Perpetual Helpfero2319Belum ada peringkat

- The Mark of AntichristDokumen5 halamanThe Mark of AntichristThe lordBelum ada peringkat

- Oratio ImperataDokumen2 halamanOratio ImperataJuliet Marie MijaresBelum ada peringkat

- Mohr Torei PDFDokumen32 halamanMohr Torei PDFRajthilak_omBelum ada peringkat

- Deep Time WItchcraftadDokumen17 halamanDeep Time WItchcraftadNorthman57Belum ada peringkat

- Growth and TransformationDokumen5 halamanGrowth and TransformationEric AfongangBelum ada peringkat

- A Bosnian Commentator On The Fusus Al-HikamDokumen22 halamanA Bosnian Commentator On The Fusus Al-Hikamhamzah9100% (1)

- Dua Al Mathoura GrandshaykhDokumen10 halamanDua Al Mathoura GrandshaykhxbismilahxBelum ada peringkat

- Hall - Panikkar Trusting The OtherDokumen23 halamanHall - Panikkar Trusting The OtherOscar Emilio Rodríguez CoronadoBelum ada peringkat

- Mp3 (23Mb, Duration 1:06:51) "Man! Know Thyself"Dokumen10 halamanMp3 (23Mb, Duration 1:06:51) "Man! Know Thyself"Olica MaximovaBelum ada peringkat

- See His Glory - BILLY FUNK LyricsDokumen4 halamanSee His Glory - BILLY FUNK LyricsDave JhonatanBelum ada peringkat

- Applied Biblical Studies of JonahDokumen3 halamanApplied Biblical Studies of JonahCasey LydenBelum ada peringkat

- Seeking Help From Anbiya and Awliya (Istighatha)Dokumen17 halamanSeeking Help From Anbiya and Awliya (Istighatha)Te100% (1)

- Sundays Made Amazingly Simple - Edition 1Dokumen3 halamanSundays Made Amazingly Simple - Edition 1Ema NedilaBelum ada peringkat

- Nyanaponika Thera Bodhi Bhikkhu (TRS) - Anguttara Nikaya. Part III Books Eight To ElevenDokumen129 halamanNyanaponika Thera Bodhi Bhikkhu (TRS) - Anguttara Nikaya. Part III Books Eight To ElevenEvamMeSuttam100% (1)

- Toronto TorahDokumen4 halamanToronto Torahoutdash2Belum ada peringkat

- The Indian Roots of Pure Land Buddhism Jan NattierDokumen23 halamanThe Indian Roots of Pure Land Buddhism Jan Nattierfourshare333Belum ada peringkat

- The Dream of The RoodDokumen2 halamanThe Dream of The Roodjwigginjr100% (2)

- Schwartzmann Gender Concepts and ProverbsDokumen17 halamanSchwartzmann Gender Concepts and ProverbsBerel Dov LernerBelum ada peringkat

- Allama Iqbal Site KhudiDokumen28 halamanAllama Iqbal Site KhudiIftikhar AhmadBelum ada peringkat

- San Carlos - Aperuit IllisDokumen18 halamanSan Carlos - Aperuit IlliskarlolaraBelum ada peringkat

- Meditation of Light ENG PDFDokumen3 halamanMeditation of Light ENG PDFAdam BoBelum ada peringkat

- Know Your EnemyDokumen83 halamanKnow Your Enemyserbisyongtotoo100% (1)

- The Evangelists of The Early ChurchDokumen4 halamanThe Evangelists of The Early ChurchKarl DahlfredBelum ada peringkat

- I. Objectives: The Learner Understands Human Beings As Oriented Towards Their Impending DeathDokumen5 halamanI. Objectives: The Learner Understands Human Beings As Oriented Towards Their Impending Deathmerry jubilantBelum ada peringkat

- Wichtig Anthropology of ReligionDokumen495 halamanWichtig Anthropology of ReligionKathrin Crsna100% (5)

- Prophetic Method of Islamic RevolutionDokumen38 halamanProphetic Method of Islamic RevolutionSayedul IslamBelum ada peringkat

- The Ophidian Sabbat: Serpent-Power and the Witch-CultDokumen119 halamanThe Ophidian Sabbat: Serpent-Power and the Witch-CultKinguAmdir-Ush86% (7)

- Message of The Saints: Thera - and Theri-GathaDokumen18 halamanMessage of The Saints: Thera - and Theri-GathaBuddhist Publication Society100% (1)

- Sermon 18-2-23 ADokumen88 halamanSermon 18-2-23 AMARIFE ORETABelum ada peringkat

- Kabbalah for Beginners: Understanding and Applying Kabbalistic History, Concepts, and PracticesDari EverandKabbalah for Beginners: Understanding and Applying Kabbalistic History, Concepts, and PracticesPenilaian: 5 dari 5 bintang5/5 (20)

- My Jesus Year: A Rabbi's Son Wanders the Bible Belt in Search of His Own FaithDari EverandMy Jesus Year: A Rabbi's Son Wanders the Bible Belt in Search of His Own FaithPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (51)

- The Goetia Ritual: The Power of Magic RevealedDari EverandThe Goetia Ritual: The Power of Magic RevealedPenilaian: 3 dari 5 bintang3/5 (5)

- When Christians Were Jews: The First GenerationDari EverandWhen Christians Were Jews: The First GenerationPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (56)

- Israel and the Church: An Israeli Examines God’s Unfolding Plans for His Chosen PeoplesDari EverandIsrael and the Church: An Israeli Examines God’s Unfolding Plans for His Chosen PeoplesPenilaian: 5 dari 5 bintang5/5 (24)

- For This We Left Egypt?: A Passover Haggadah for Jews and Those Who Love ThemDari EverandFor This We Left Egypt?: A Passover Haggadah for Jews and Those Who Love ThemPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (8)

- What Every Christian Needs to Know About Passover: What It Means and Why It MattersDari EverandWhat Every Christian Needs to Know About Passover: What It Means and Why It MattersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (4)

- The Pious Ones: The World of Hasidim and Their Battles with AmericaDari EverandThe Pious Ones: The World of Hasidim and Their Battles with AmericaPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (7)

- The Chicken Qabalah of Rabbi Lamed Ben Clifford: Dilettante's Guide to What You Do and Do Not Need to Know to Become a QabalistDari EverandThe Chicken Qabalah of Rabbi Lamed Ben Clifford: Dilettante's Guide to What You Do and Do Not Need to Know to Become a QabalistPenilaian: 5 dari 5 bintang5/5 (42)

- Kabbalah: Unlocking Hermetic Qabalah to Understand Jewish Mysticism and Kabbalistic Rituals, Ideas, and HistoryDari EverandKabbalah: Unlocking Hermetic Qabalah to Understand Jewish Mysticism and Kabbalistic Rituals, Ideas, and HistoryPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (2)