Ndep-Line-Winter 2014

Diunggah oleh

api-235820714Judul Asli

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Ndep-Line-Winter 2014

Diunggah oleh

api-235820714Hak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

NDEP-Line

From the Chair...

Rayane AbuSabha

Professor and Graduate Program Director

The Sage Colleges Nutrition Science Department

Troy, New York

abusar@sage.edu

Winter 2014

In this issue:

From the Chair .................1

From the Editor..................3

2015 Area Meeting

Save the Date .....3

Guidelines for Authors...4

NDEP Officers....................4

While I sadly watch another short and cool summer slip by, as the

incoming chair of NDEP I cannot help but be thrilled about all the

exciting projects NDEP is working on this year. Before I discuss FNCE,

let me highlight a few things NDEP accomplished this past year.

Off with the NDA

This past year was quite a busy year for our membership. The

surprising announcement of the NDA (Nutrition and Dietetic Associate)

designation at FNCE in Houston was a topic of much debate for us

educators. Educators took a stand and spoke out against the premature

decision for this new designation/credential which led the Academys

Board of Directors to appoint a Task Force to look more closely at

moving to multi-levels of practice. The Task force recommended

dropping the NDA and building on the DTR Pathway III following many

of the educators suggestions. Needless to say, thanks to the hard work

of the Task Force members (including our own NDEP Past-Chair Julie

O-Sullivan Maillet) and the BODs latest vote, our faith in the process

followed by our Academy leaders has been restored. For sure we hit a

few bumps, but we are facing a crisis and these snags may have been

necessary to arrive to the best solution for our students and the future

of the profession.

Utilization of NutritionFocused Physical

Assessment in Dietetic

Curriculum.........................5

Organizing an

Interprofessional

Service Learning

Event................................9

Application and

Student Perceptions

of a Flipped Teaching

Model in a Life Cycle

Nutrition Course ............12

If Nutrition Is Your

Profession, Then

Public Policy Is

Your Future? ...................15

Best Practices in

Food Systems

Management and

Quantity Foods

Production..................... 18

2 | NDEP-Line | Winter 2014

A New, Stronger NDEP

We are slowly but surely moving to a stronger

presence of educators in the dietetics field and

within the Academy. Last year, we had several of

our newly formed NDEP task forces hard at work

on education issues: They attended the

International Interprofessional Education

conference in Vancouver, Canada to represent

dietetic education, they sent out surveys and

collected data from members to begin sharing

best practices on simulations and ideas to serve

you better, they recommended DICAS updates

based on member input and they developed new

recommendations for the second round dietetic

internship match: kudos to all our task force

members! At the Academy level, NDEP was

invited to appoint a representative to sit on the

Council on Future Practice. Patti Landers has

kindly agreed to be our representative for the

2014-2015 year. BOD and CDR liaisons were

also appointed to the NDEP Council to provide

us with updates on their activities and represent

educators to their boards.

Plans for the Coming Year

For this coming year, our plans are to build the

solid base for the future of this new and stronger

NDEP. Enticing practitioners to become

preceptors is one of our priorities. In addition to

the Preceptor Recruitment Fair held at FNCE,

NDEP plans to begin a series of nutrition

webinars presented by educators and made

available free of charge to NDEP members and

preceptors. Further, I have developed a

webpage off my departments website

(sage.edu/nutrition) that provides preceptors with

a hub for courses and modules that award free

continuing professional education. Feel free to

share this page with your preceptors as one of

the many perks of serving as a great mentor. The

page can be accessed at:

www.sage.edu/nutrition-ceus. If you know of

other free CPEU opportunities please share them

with me and help me keep this page up-to-date.

Finally, this year I will be researching the matter

of providing educators with CPEs just for acting

as preceptors, as is the case

with the Occupational Therapy field supervisors

who are rewarded for mentoring students with 18

units every three years by their credentialing body

NBCOT.

Helping faculty is another priority of the NDEP

Council. We are currently collaborating with the

Informatics DPG to develop a toolkit for educators to

introduce informatics throughout the dietetics

curriculum. Likewise, my hope is that we will work to

develop similar educational toolkits on the topics of

public policy and advocacy, two challenging subjects

for most programs. These are only but a few of the

many plans your NDEP leadership has at work.

On to FNCE 2014

Your NDEP Council was very busy at the Food and

Nutrition Conference and Exhibition this October

2014. It was wonderful seeing so many of you at our

NDEP Member Breakfast and Meeting on Sunday

when we heard updates from ACEND and CDR. The

NDEP education session submitted by our IPE Task

Force for FNCE Using Teamwork to Promote

Improved Patient Outcomes was extremely well

attended and received rave reviews. The NDEP

Student Internship fair on Sunday was packed with

over 700 students attending. The room was smaller

than originally requested which led to a crowded

space. We are making every effort to ensure a larger

space for next year. Finally, NDEP arranged the

meeting with the Association of Nutrition

Departments and Programs (ANDP, also known as

the nutrition department chairs of research

institutions) and ACEND, CDR and CFP to improve

communications between the Academy groups and

ANDP. The meeting was an overall success with the

plan for NDEP to arrange such a meeting every year

at FNCE. Thanks to all our wonderful task force

members and our NDEP Council members for

volunteering their time so generously and ensuring

the success of the NDEP activities at FNCE 2014.

Have a wonderful and productive year!

Rayane

3 | NDEP-Line | Winter 2014

From the Editor...

Robyn Osborn, PhD, RD

robyn.osborn@va.gov

Greetings! Effective with this issue, I am your new NDEP-Line Editor. If you wish to submit articles or

announcements relevant to dietetic education to NDEP-Line, please send them to me. We are always

looking for announcements or articles of interest to other educators and preceptors, including program

innovations and best practices.

The photos from 2014 NDEP Breakfast at FNCE in Atlanta are available in the NDEP Portal. The link to

the portal is http://ndep.webauthor.com.

2015 Area Meetings - -Save the Date

Area 1 Sunday, March 15th Tuesday, March 17th

Location: Asilomar Conference Grounds, Pacific Grove, CA

Rates: $241.57/night plus tax for a single room or $156.96/night plus tax for a double room. Room cost includes three meals per

day and tourism and facility fees. Please click on the following link to book a room at Asilomar:

https://resweb.passkey.com/Resweb.do?mode=welcome_ei_new&eventID=12522214.

Regional Directors Contact Information: Miriam Ballejos - medlefsen@comcast.net and Anne Shovic - shovic@hawaii.edu

Area 2/5 March 26-27, 2015 in Minneapolis/St. Paul, Minnesota

Hotel: Hilton Minneapolis/St. Paul Hotel, 3800 American Blvd, Bloomington, MN - $149/night plus tax (currently 14.28%). For

reservations, please call 952-854-2100 and state you are attending the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics NDEP meeting. Hotel

parking and Wi-Fi access are complimentary. Registration information to follow.

Additional Information: The meeting will start around 8:30am on Thursday, March 26 and end by 1pm on Friday, March 27.

Regional Directors Contact Information: Julie Kennel kennel.3@osu.edu and Laurie Kruzich - lkruzich@iastate.edu

nd

Area 3/4 Friday, May 1st Saturday May 2 in Denver, Colorado

Hotel: Sheraton Denver Downtown Hotel 1550 Court Place, Denver, CO - $159/night plus tax (currently 14.85%). To make a

reservation, please call 303-893-3333 and state that you are attending the NDEP Area 3/4 Meeting. Registration information to

follow.

Regional Directors Contact Information: Susan Miller - miller1@uab.edu and Kristy Becker - kristy.becker2@va.gov

th

Area 6/7 Thursday, April 9th Friday April 10 in State College, Pennsylvania

Hotel: The Penn State Conference Center Hotel - $119/night plus tax (currently 8.5%). Hotel shuttle to and from the airport and

downtown State College, Wi-Fi access, and parking are complimentary.

Additional Information: It is highly recommend to make your travel plans early especially if you plan to fly to the meeting.

Meeting website link: http://sites.psu.edu/ndeparea6and7/

Please note that the webpage will be a work in progress. Information will be added as it becomes available.

Regional Directors Contact Information: Mary Dean Coleman - mdc15@psu.edu and Suzanne Neubauer

sneubauer@framingham.edu

Early bird meeting registration for all meetings will be $175 for NDEP members, $215 for Academy members, and $250 for nonAcademy members. Note: Fees increase by $30 to a standard rate. Fee schedules are determined by meeting and will be released

with registration information in January. Refer to the NDEP website at www.ndepnet.org for details, to be posted.

4 | NDEP-Line | Winter 2014

Guidelines for NDEP-Line

Authors

NDEP-Line features viewpoints,

statements, and information on

materials and products for the use of

Nutrition and Dietetic Educators and

Preceptors (NDEP) members. These

viewpoints, statements and information

do not imply endorsement by NDEP

and the Academy of Nutrition and

Dietetics. Articles may be reproduced

for educational purposes only. NDEPLine owns the copyright of all published

articles, unless prior agreement was

made.

NDEP Officers:

A submission may be returned to

the primary author for revision if it

does not conform to the style

requirements.

Copyright 2012 by Nutrition and

Dietetic Educators and Preceptors of

the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics.

All rights reserved. No part of this

publication may be reproduced, stored

in a retrieval system or transmitted in

any form by any means without

permission of the publisher.

Article length

Article length is negotiated with the

editor for the issue in which it will

appear. Lead articles are usually

around 2,000 words. Other feature

articles are 1,000-1,500 words,

while book reviews and brief reports

are 500 words.

For authors in other

fields/disciplines:

Anthony T. Vicente, PhD, Director,

Nutrigenomics Laboratory,

American Human Nutrition

Research Center on Genetics at

American University

Text format

All articles, notices, and information

should be in Times New Roman

font, 12 point, single-spaced.

Tables and illustrations

Tables should be self-explanatory.

All diagrams, charts and figures

should be camera-ready. Each

illustration should be accompanied

by a brief caption that makes the

illustration intelligible by itself.

References

References should be cited in the

text in consecutive order

parenthetically. At the end of the

text, each reference should be

listed in order of citation. The format

should be the same as that of the

Journal of the Academy of Nutrition

and Dietetics.

Author(s)

List author with first name, initial (if

any) last name, professional suffix,

and affiliation (all in italics) below

the title of the article, i.e., For

NDEP members or other dietetic

educators:

Anne A. Anderson, PhD, RD, LD,

American University

Authors Contact Information

Before the article, give the primary

authors complete contact

information including program

affiliation, phone, fax and email

address.

Submission

All submissions for the publication

should be submitted to the editor as

an e-mail attachment as an MS

Word file. Indicate the number of

words after authors contact

information.

Rayane AbuSabha

Chair

abusar@sage.edu

Sylvia Escott-Stump

Chair-Elect

escottstumps@ecu.edu

Patti Landers

Past Chair

Patti-Landers@ouhsc.edu

Miriam Edlefsen Ballejos

Area 1 Regional Director

medlefsen@wsu.edu

Anne Shovic

Area 1 Regional Director

shovic@hawaii.edu

Laurie Kruzich

Area 2 Regional Director

lkruzich@iastate.edu

Susan Miller

Area 3 Regional Director Lead Director

Miller1@uab.edu

Kristy Becker

Area 4 Regional Director

Kristy.Becker2@va.gov

Julie A Kennel

Area 5 Regional Director

jkennel@ehe.osu.edu

Mary Dean Coleman

Area 6 Regional

Director

mdc15@psu.edu

Suzanne Neubauer

Area 7 Coordinator

sneubauer@framingham.edu

Renee Walker

Preceptor Director

Renee.walker2@va.gov

Submission Deadlines

Spring:

February 1

Summer:

May 1

Fall:

August 1

Winter:

November 1

Ruth Johnston

Portal Manager & HOD

Liaison

Ruth.Johnston@va.gov

Editor

Robyn Osborn, PhD, RD

VA San Diego Health care System

Phone: 858-552-8585 x 2407

Robyn.osborn@va.gov

Kathryn Hamilton

CDR Liaison

Reprint permissions request or

back issues:

Contact Robyn Osborn @

robyn.osborn@va.gov

Margaret Garner

BOD Liaison

mgarner@cchs.ua.edu

Julie Plasencia

Graduate Student Representative

Public Member

TBD

Dorothy Chen-Maynard

Journal Initiative Chair

dchen@csusb.edu

Robyn A Osborn

NDEP-Line Editor

Osborn_robyn@yahoo.com

Joan Frank

Applicant Guide Chair

jsfrank@ucdavis.edu

Lauren Florian

Academy Liaison

lflorian@eatright.org

5| NDEP-Line | Winter 2014

Utilization of Nutrition-Focused Physical

Assessment in Dietetic Curriculum

Dema Halasa-Esper MS, RDN, LD

Sue M. Leson, PhD, RDN, LD

Jeanine L. Mincher, PhD, RDN, LD

Rachael J. Pohle-Krauza, PhD, RDN

Zara C. Shah-Rowlands, PhD, RDN, LD

Youngstown State University, Department of Human Ecology, Food and Nutrition

dhesper@ysu.edu

330-941-3344

Background

New federal and state guidelines on the diagnosis

of malnutrition and reimbursement for related care,

requires that dietitians and other healthcare

providers become more vigilant and proactive in

providing successful interventions to prevent or

delay, reverse and limit malnutrition in care settings.

Physical assessment and examination skills are

needed to recognize the insidious effects of

malnutrition. Although physicians, nursing staff,

and other health professionals already perform

physical exams on patients, dietitians can utilize

Nutrition Focused Physical Assessment (NFPA) to

evaluate nutritional risk and determine more

effective nutrition interventions. NFPA techniques

assess for overt signs of nutritional deficiency, skin

integrity, organ function, and loss of muscle and

subcutaneous fat stores.

Healthcare reimbursement is scrutinized based on

clinical outcomes; therefore clinicians need to

exhibit care plans that show cost saving measures.

The Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics has

addressed this issue by asking the Council on

Future Practice (CFP) to project and plan for the

future needs of the dietetics profession by providing

guidance and recommendations on this topic in

their detailed report title Moving Forward A Vision

for the Continuum of Dietetic Education,

Credentialing and Practice. The impetus for our

Department to implement NFPA training through

the curriculum comes from parts of this report, as

well as preliminary data our colleagues have

collected over the past three years, which focus on

the incorporation of and training in NFPA in

undergraduate dietetic education.

Although the Accreditation Council for Education in

Nutrition and Dietetics (ACEND) has published

standards that allow currently accredited dietetics

programs to assimilate NFPA skill development into

coursework, Registered Dietitians Nutritionists

(RDNs) already in practice may have not yet been

trained in putting new assessment guidelines into

practice. In addition, all healthcare facilities have

not adopted new guidelines on malnutrition;

therefore, many have not made significant progress

toward training their dietetics staff on NFPA

techniques.1

Vision for Dietetics Education

Nutrition-related problems are best identified

through the Nutrition Care Process (NCP),

completed by RDs/RDNs. Here, objective and

subjective data are gathered in order to complete a

thorough nutrition assessment, which is the first

element of the NCP. Nutrition-focused physical

assessment is an important part of the fivecomponent approach to nutrition assessment, but

often not performed due to a lack of education and

training.2

Our ongoing goal is to incorporate more physical

assessment training into our CPD program at

Youngstown State University, along with

competency testing. It is our hope that such

training will reduce the reluctance of RDNs in

performing physical examinations. 3 Because of

this, a primary objective was to create and

6| NDEP-Line | Winter 2014

implement an educational program that would allow

preceptors, in addition to students, to be trained in

performing NFPA skills. This program will also

allow our department to further collaborate with

dietetic professionals who mentor our students

during their supervised practice experiences,

thereby, segueing classroom instruction into

supervised practices experiences. Currently, we

use case-based didactic approaches when applying

the NCP, but it is through hands-on training that

students will gain the self-assurance and skills set

necessary to perform NFPA as part of the NCP.

This will lead to confidence in using physical

assessment skills in their dietetic internship

experience and training, which will be translated

into future practice in nutrition and dietetics.

The interest in pursuing hands-on NFPA training in

dietetic education came from preliminary data

collected from a structured, internet-based survey

administered to RDs in the state of Ohio, who were

members of the American Dietetic Association. 4

The results of this survey revealed a significant

relationship between practitioner use of NFPA,

length of time in practice, and presence of

specialized certification. The RDs who used NFPA

received education and training mostly through a

conference/seminar and supervised practice. This

affirmed to our faculty that NFPA education should

be incorporated into the CPD curriculum. In

addition, we also gained insight into the necessity of

clinical preceptor involvement as part of the

ongoing effort to increase NFPAs emphasis in the

current curriculum.

Innovation in Dietetic Education with Expected

Outcomes

We have already seen the value of incorporating

NFPA training into the curriculum of supervised,

clinical practice for first year students in the CDP at

Youngstown State University. In 2011, we

conducted a pilot NPFA training in two four-hour

sessions as demonstration and simulation lectures

in each of the following subjects: body composition

(bioelectrical impedance and skinfold analysis,

muscle and subcutaneous fat assessment),

anthropometric indices (height, body weight, waist

circumference, arm span, and knee height), indirect

calorimetry (via Medgem), vital sign measurement

(temperature, pulse, respiration rate, blood

pressure, and blood glucose via finger stick), and

respiratory system assessment (review of thoracic

examination, breathing patterns and auscultation of

breath sounds). 4 All students ranked their interest

in NFPA as or greater based on a scale of 10, while

more than 90% of students ranked their likelihood

of using NFPA in future practice as a 7 or greater.

We concluded that the implementation of NFPA in

dietetic education might well have a prolonged and

favorable impact on students nutrition assessment

skills set and future dietetic practice. Our next step

is to incorporate these demonstration and

assimilation modules in NFPA into a course

curriculum for all dietetic students; however NFPA

skill assessment and competencies testing will be

completed with CPD students (junior and senior

years) and our preceptors in clinical, community,

maternal and child, and aging care practice settings

in order to ensure novice/beginner NFPA skills.

This will allow our dietetic program to further

expand our training to all students pursuing an

undergraduate degree in nutrition and dietetics at

Youngstown State University, both DPD and CPD

tracks.

Future Dietetics Education Plan with Expected

Outcomes

The diagnosis of malnutrition and reimbursement

for related care requires that dietitians become

more vigilant and proactive in identifying

malnutrition. The Academy of Nutrition and

Dietetics and the American Society for Parenteral

and Enteral Nutrition (ASPEN) have developed a

set of guidelines that, when used consistently and

accurately, can demonstrate the presence of

malnutrition, which can facilitate the physicians

ability to recognize and appropriately diagnose

malnourished patients.5 It is of note that four of six

criteria that should be used in order to generate this

diagnosis pertain to physical assessment of muscle

and fat mass, fluid accumulation, and grip strength.

And while malnutrition identifiers have always been

included to some degree in the nutrition

assessment process, linking them with current NCP

terminology (NCPT) may assist practitioners with

visualizing why and where NFPA fits into their

scope of practice and day-to-day provision of care

activities (Figure 1). Using NFPA will only enhance

7| NDEP-Line | Winter 2014

the dietitians ability to help to prevent, identify,

and/or delay the outcomes of malnutrition in

multiple care settings.

Dietetic educators can significantly contribute to the

building of didactic and skill development of

nutrition assessment; thus impacting RDNs role in

future practice. The benefit of and suggestions on

how to implement NFPA into dietetic curriculum are

detailed in Table 1. It is our recommendation to

program directors and educators to start small and

build gradually. The elements of NFPA skill

acquisition can be based on the novice and

beginner levels from the Career Development

Guide (CDG) as listed in the Academy Practice

Paper Critical Thinking Skills in Nutrition

Assessment and Diagnosis.7 Consider incorporating

elements of NFPA skills into several courses so

these concepts can be reinforced and addressed

through various dietetic settings (e.g. clinical,

community, maternal and child, and aging). This is

certainly an exciting time for our profession with

RDNs being recognized for professional skills,

knowledge, and the ability to impact healthcare

outcomes.

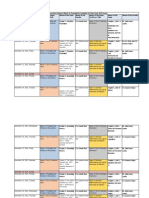

Figure 1: Nutrition Care Process Terminology and Malnutrition Characteristics. Adapted from (5) and (6).

Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, Nutrition Care Process Terminology Reference Manual (eNCPT)

Copyright 2013. http://ncpt.webauthor.com

8| NDEP-Line | Winter 2014

Table 1: Benefits of and Suggestions for Implementation of NFPA into Dietetic Curriculum

Benefits

Provide cutting-edge educational

experiences can set your program apart.

Enable increased recognition of the

RDs/RDNs in the functioning of the health

care team.

Provide team experiences/collaboration for

students.

Increase the likelihood of future

reimbursement for nutrition services.

Students can develop novice level NFPA

skills prior to starting entry-level practice

Suggestions for Implementation

Faculty will need to engage in curriculum mapping to see

where and how NFPA can be incorporated into existing

courses.

Faculty will need to utilize resources already present:

- Colleagues on campus

- Already existing lab space and

equipment

- Shared simulation lab space

Faculty will need to obtain training and identify content experts

among the nutrition faculty.

Faculty will need to consider preceptors in the training as well

if supervised practice is part of the program.

Consider forming a joint Assessment Lab that is shared by

Allied Health Faculty and Students.

References:

1. Patel V, Romano M, Corkins MR, et al. Nutrition

screening and assessment in hospitalized

patients. A survey of current practice in United

States. Nut Clin Pract. 2014; 29:483- 490.

2. Cohen DA, Tougher-Decker R, Matheson P,

Byham-Gray J, OSullivan-Maillet. Physical

assessment knowledge and skills taught in dietetic

internships and coordinated programs. J Am Diet

Assoc. 2007; 107.

3. Halasa Esper D, Pohle-Krauza R. J., Leson S. M.

Nutrition Focused Physical Assessment:

Preceptors Education, Application and Perceived

Barriers. (Abstract). J AM Diet Assoc. 2010; 110

(9): A32.

4. Halasa-Esper D, Converse A, Yacovone ML,

Pohle-Krauza RJ. A Training Program in NutritionFocused Physical Assessment for Dietetics

Students. J Academy of Nutr Diet. 2012; 112 (9):

A27.

5. White J, Guenter P, Jenson G et al. Consensus

Statement of the Academy of Nutrition and

Dietetics/American Society for Parenteral and

Enteral Nutrition: Characteristics Recommended

for the Identifications and Document of Adult

Malnutrition (Undernutrition). J Acad Nutr Diet.

2012; 112:730-738.

6. Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, Nutrition Care

Process Terminology Reference Manual (eNCPT).

Accessed December 1, 2014.

http://ncpt.webauthor.com

7. Practice Paper of Academy of Nutrition and

Dietetics: Critical Thinking of Nutrition Assessment

and Diagnosis. 2013.Accessed at

www.eatright.org/members/practicepapers

NDEP Website www.ndepnet.org

NDEP Portal http://ndep.webauthor.com

As an NDEP member, you are automatically entered into the portal and

have use of the EML system. Log in using your Academy log in and

password. To send a message to the NDEP EML, email

ndep@ndep.webauthor.com. To attach documents directly to your

message, you must send the message to this email address from your

email. Documents posted to messages submitted in the portal will not be

attached to the email message.

Questions email ndep@eatright.org

9| NDEP-Line | Winter 2014

Organizing an Interprofessional Service

Learning Event

Nina Roofe, PhD, RDN, LD, FAND

Assistant Professor & Dietetic Internship Director

Department of Family & Consumer Sciences

University of Central Arkansas

nroofe@uca.edu

501-450-5950

Purpose and Rationale

Development of interprofessional skills is a

critical component in didactic and supervised

practice educational programs. The World

Health Organization defines Interprofessional

Education (IPE) as when students from two or

more professions learn about, from and with each

other to enable effective collaboration and

improve health outcomes. The expectation of a

patient-centered health care team starts at the

undergraduate level.1 Didactic programs in

dietetics promote IPE and teamwork while

addressing barriers and challenges.2

Competencies for IPE programs encompass four

domains including values and ethics; roles and

responsibilities; interprofessional communication;

and teams and teamwork.3-5 All team members

should be trained with a community-oriented,

patient centered mindset (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Interprofessional Collaborative Practice Domains

Interprofessional Communication Practices

Roles and Responsibilities for Collaborative

Practice

Community Oriented

Patient Centered

Interprofessional Teamwork and Team-Based

Practice

Values / Ethics for Interprofessional Practice

10| NDEP-Line | Winter 2014

Faculty Involvement

Developing a culture for IPE requires faculty from

multiple disciplines who are trained in and value

IPE and are willing to work together to co-create

a shared vision, common goals, and

experiences.6-8 The event described here is a

campus-wide health fair for faculty, staff, and

students. This IPE event is one section of the

health fair. Two faculty members were assigned

to each of the four areas of health information

regarding obesity (definition, screening,

prevention, or treatment) to oversee and assist

student efforts. Prior to the health fair, faculty

from multiple disciplines provided education and

instruction to their respective students. This

education and training focused on

interprofessional health care collaboration, scope

of practice of various health care providers, and

applicable licensure laws.

Student Involvement

The students were challenged with the task of

creating education and screening materials

focused on obesity prevention and treatment.

Four sections were identified for organizational

purposes including (1) Definitions/Risk Factors,

(2) Screening, (3) Prevention, and (4) Treatment.

Students from eight departments collaborated on

each content area section of the health fair. The

eight departments were Health Sciences,

Kinesiology, Nursing, Nutrition, Occupational

Therapy, Physical Therapy, Psychology, and

Speech Language Pathology. A true

interdisciplinary model was used with all

departments represented in each content area as

opposed to a multidisciplinary model. The goal

was not to have a nutrition section, nursing

section, physical therapy section, etc., but rather

to provide a venue for students from each

department to collaborate on a given content

area.

Students created informational displays using

criteria from the CDC, USDA, and the Academy

regarding body mass index categories as well as

obesity risk factors and comorbidities. These

displays provided specific information regarding

definitions and screening criteria for obesity.

Screenings were conducted at the next section

including measurements of body mass index,

waist to hip ratio, body composition, and a family

health history. The third section was focused on

prevention and provided information on lifestyle

assessment, strategy development, goal setting

and local resources to support nutrition, exercise,

and stress management. The final section

showcased evidence-based treatment options for

obesity including prescription medications,

bariatric surgery, and weight management

programs.

Steps in event planning are outlined below to

serve as a guide for implementation and can be

adapted to fit specific department or college

parameters.

1. Secure administrative and faculty support.

a. College Dean established one day during

the term as IPE Day for students to

participate in the event. This was

communicated to all faculty in the college

to allow students involved to be excused

from class for the purpose of the event. If

students were enrolled in courses outside

the college, a letter from an IPE faculty

member was written to request the

student be excused for this event.

b. Department Chairs encouraged faculty to

support the event and to tie participation

to course objectives in appropriate

classes. In this case, the event is part of

the capstone Nutrition Senior Seminar

course.

c. Faculty planned ahead for this event

when writing their course syllabi and

course schedule. Additionally the course

content included education and training

on IPE as well as a reflection assignment

for points in the course.

2. Identify assessment/record-keeping

needs.

a. Attendance records to report level of

participation for university, college, and

departmental outcome measures

b. Follow-up surveys or focus groups to

identify what worked well and areas for

improvement for future events.

3. Identify the number of students in each

department who would participate in the

event.

a. Each department compiled a list of

students and their preferred email

addresses

b. The number of students in each

department was equally (as much as

possiblesome departments did not have

an even number of students) divided

among the areas of the health fair.

4. Determine topics for each section and

divide students evenly in each section.

a. Each group looked at the scope of each

discipline involved in relation to their

assigned section of the health fair.

11| NDEP-Line | Winter 2014

b. Areas of overlap were identified as well as

areas of delineation, e.g. nursing staff

administer medications while nursing,

nutrition, and health science staff address

food drug interaction education.

c. The students met several times before the

event to plan, review scope of practice

and licensure laws, delineate roles, and

collaborate on how to address their

assigned areas.

d. Once assigned areas were identified,

each group created the content for their

displays and interactive booths:

i.

Definition/Screening Criteria:

informational displays using criteria

from the CDC, USDA, etc. regarding

BMI definitions, risk factors, and comorbidities.

ii.

Screening: performed BMI

calculations, waist to hip ratio, body

composition analysis, and a family

health history.

iii.

Prevention: conducted a lifestyle

assessment and provided information

on goal-setting, local resources and

strategy development, e.g. nutrition,

exercise, stress management,

awareness of risk factors, and

genetics.

iv.

Treatment: showcase of current

treatments with scientific evidence

base and local resources, e.g. Rx

meds, bariatric surgery, weight

management programs.

5. Assess and Debrief

a. Administered surveys and conducted

focus groups as planned.

b. Determined impact on students in terms

of teamwork, communication, and comfort

with health care collaborations through

student reflection.

c. Shared information on attendance and

impact with interested stakeholders:

students, faculty, and staff.

Discussion

The ability of healthcare providers to work as a

team is crucial for optimal patient care. In fact,

the Interprofessional Education Collaborative

(IPEC) has established interprofessional

teamwork and team based practice as one of the

four interprofessional collaborative practice

domains. 3 Creating experiences that allow for

interaction with multiple disciplines in the health

sciences provides a context for practicing

communication and teamwork skills.9

Participation gives students an opportunity to

begin to understand the necessity of

communication and how to function as a team in

order to provide optimal patient care. These

events can be documented on a students

resume which may be of interest to prospective

employers and graduate education programs.

Faculty involvement is critically important for

student training and modeling of collaboration

with faculty from other departments.10 Looking

ahead to actual practice settings, we can

anticipate that teamwork and collaboration can

decrease error and enhance quality of care. It

stands to reason that learning these skills during

academic and clinical training will increase the

possibility that graduates will be skilled at

collaboration and teamwork, leading to improved

patient outcomes.

References

1. World Health Organization. Framework for action

on interprofessional education & collaborative

practice [internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): World

Health Organization; 2010.

Available from:

http://www.who.int/hrh/resources/framework_actio

n/en/

2. Heiss CJ, Goldberg LR, Brady H. Service-learning

in dietetics courses: A benefit to the community

and an opportunity for students to gain dieteticsrelated experience. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012;

112(10): 1524-7.

3. Bainbridge L, Nasmith L, Orchard C, Wood V.

Competencies for interprofessional collaboration.

JOPTE. 2010; 24(1): 6-11.

4. Bridges DR, Abel MS, Carlson J, Tomkowiak J.

Service learning in interprofessional education: A

case study. JOPTE. 2010; 24(1): 44-50.

5. Interprofessional Education Collaborative. Core

competencies for interprofessional collaborative

practice: Report of an expert panel [Internet].

Washington DC: Interprofessional Collaborative;

2011 May. 56 p. Available from:

http://www.aacn.nche.edu/educationresources/ipecreport.pdf

6. Bringle RG, Hatcher JA. Innovative practices in

service-learning and curricular engagement. New

Directions for Higher Education. 2009 Fall; 147:

37-46.

7. DEon M. A blueprint for interprofessional learning.

Medical Teacher [Internet]. 2004. 26(7): 604-9.

Available from:

http://informahealthcare.com/doi/abs/10.1080/014

21590400004924.

8. Institute of Medicine. Health professions

education: A bridge to quality. Washington DC:

The National Academies Press; 2003 Apr 18,

p.176.

12| NDEP-Line | Winter 2014

9. Institute of Medicine. Educating for the health

team: Report of the conference on the

interrelationships of educational programs for

health professionals. Washington DC: The

National Academies Press; 1972 Oct., p39.

10. Solomon P, King S. Online interprofessional

education: Perceptions of faculty facilitators.

JOPTE. 2010; 24(1): 3.

Application and Student Perceptions of a

Flipped Teaching Model in a Life Cycle

Nutrition Course

Renee D. Barrile, PhD, RD, LDN

Lecturer, Clinical Laboratory and Nutritional Science

University of Massachusetts Lowell

Renee_Barrile@uml.edu

978-934-4457

Flipping a class refers to a model of teaching that

reverses the traditional classroom lecture to

something that students do at home before coming

to class. In other words, students learn the material

on their own time by watching pre-taped lectures

and/or assigned readings and during class time

they participate in activities to enhance learning.

There are many potential benefits to this model.

One is that students come to class prepared with

the basic information, allowing class time to be

dedicated to hands-on learning activities. Students

can then apply knowledge under the guidance of

their instructor while working collaboratively with

their peers.1

The idea of a flipped classroom has been gaining in

popularity since articles about the model have

appeared in a range of publications from the NY

Times2 to the scholarly journal Science.3 While

limited, there is some quantitative data to suggest

students do learn material to a greater extent when

being taught in this manner. In one example, a

physics class was taught in a traditional manner at

the start of the semester. Later, one section used

reading assignments and quizzes to introduce

material, and class time was used for small group

discussion and questions delivered through clickers

and written responses. At the end of the course,

grades on a multiple choice test were significantly

higher from the section taught with the flipped

model compared to the control section. The flipped

class also scored higher on student engagement as

assessed by trained observers.4 Another University

used a flipped model in a challenging engineering

course. This flipped model required students to

watch lecture videos from the Massachusetts

Institute of Technology and used class time for

discussion. Initial data show the method is leading

to higher test scores compared to sections taught in

a traditional lecture only format.5

There are several ideas and suggestions to ensure

students are learning the material in a flipped class.

This is important because the material is being

introduced outside normal class time so that the

time used for in class activities is productive.

Initially, instructional materials like pre-taped

lectures or targeted readings with some type of

incentive to use these materials before coming to

class is critical to introduce material that is to be

learned. Secondly, students must be evaluated to

ensure learning is taking place. Lastly, the activities

that take place during the class time should allow

students to apply what they have learned in the

taped lectures or readings and enhance critical

thinking and problem solving skills.6

In the Spring of 2014, I used a flipped teaching

model in a Life Cycle nutrition course. To do this,

assigned readings, quizzes, and in class group

activities were utilized for selected topics

throughout the semester. The objective of making

some classes flipped was to better engage

students, foster more critical thinking and problem

13| NDEP-Line | Winter 2014

solving skills and encourage collaborative learning.

For the flipped topics, the start of class included an

open note quiz to ensure students had completed

the reading assignment and came to class

prepared. The rest of class was dedicated to small

group activities that allowed students to apply what

they had learned in the readings. Short quizzes

provided incentive for preparing for class, and

points were awarded for turning in a finished

product from the small group activities. The material

the students were quizzed on was the more basic

material and was taken directly from the assigned

reading. All of the in-class activities were completed

in small groups and required some type of

documentation that was submitted at the end of the

class. The activities did require some background

information, which was covered in the reading, and

were planned to help achieve overall course

objectives. The effectiveness of the flipped model

was assessed with a brief, voluntary, and

anonymous survey given on the last day of class.

Of the 41 students enrolled in the course, 35

provided informed consent and completed the

survey on the last day of class. The survey

included 5 questions pertaining to student learning,

student engagement, critical thinking and problem

solving skills, and class preparedness. These

questions were asked using a Likert scale from 1-5

with 1 indicating the student liked the flipped model

much better than the traditional model, 2 indicating

the student liked it better than the traditional model,

3 indicating they thought flipped vs. traditional were

the same, 4 indicated the flipped model was worse

than traditional, and 5 indicating the flipped model

was much worse. The average score for all 5

questions using the Likert scale was around 2,

indicating most students preferred the flipped model

over the traditional model. The highest average

score was for student engagement where 91% of

students felt the flipped model was much better or

better than the traditional model. The majority of

students (83%) also felt the flipped model was

much better or better at fostering critical thinking

skills, 77% felt it was much better or better at

helping them come prepared for class, and 74% felt

it was much better or better at fostering problem

solving skills.

The survey also included open ended questions

that were intended to elicit feedback that could be

used for future planning purposes. The responses

echoed the responses to the Likert scale questions

in that comments were generally positive about the

flipped model, and many students reported that

they found the flipped classes more interesting and

engaging than a normal lecture. A few also noted

that they enjoyed being able to apply knowledge,

get up and move during class, and interact with

their classmates. Some also cited benefits in their

critical thinking and communication skills. A few

students also found the assigned reading and

quizzes made studying for regular exams easier.

When asked what they did NOT like about the

flipped classes, the majority of those that

responded made reference to the quizzes on the

assigned reading given at the start of the flipped

classes. There were many reasons for not liking

the quizzes including the general stress and extra

work of having to read and take a quiz and more

specific critiques about the quizzes themselves.

For example, one student felt that the quizzes were

inconsistent and another noted they didnt know

how to prepare for them. Others do not like

learning by reading and would prefer taped lectures

and a few did not feel like the reading prepared

them for the in-class activities enough. There were

also some comments about the activities

themselves. One student commented that they did

not like working in groups and two students noted

they liked certain activities better than others.

The last open ended question asked what could be

done to make the flipped classes better. While

many chose to leave this question blank, the most

common written response was wanting more time

to complete the in-class activities. A few students

also suggested that more of the classes be flipped.

Others made suggestions to improve the seemingly

least favorite aspect of the flipped class, the

quizzes. Ideas included not having them, not

grading them, giving more guidance on what would

be on them, and making them worth extra credit. A

few students commented on the activities. One

student requested more interesting activities and

three others wanted more information on what the

activity would be before coming to class.

Analysis of the survey results was valuable in

planning for future sections of this course. First

and foremost, I will continue to utilize the flipped

model in place of some of the traditional lectures. I

will also make specific changes based on the

feedback. For example, I will include a brief

description of the in-class activity in the syllabus so

14| NDEP-Line | Winter 2014

students will feel more prepared for class. I will

change the requirements of some of the activities

so students will have enough time to fully complete

the in-class assignments. Although the open note

quizzes were clearly the least desirable aspect of

the flipped class, I will continue to include them and

grade them because it was an efficient and effective

way to ensure students prepared for class.

However, I will add specific learning objectives for

each class in the syllabus, which can help guide

students to important concepts to prepare for

quizzes and the in class activities.

The initial workload to plan and prepare flipped

classes is certainly greater for both student and

instructor. However, some students noted

preparing for the flipped classes made studying for

regular exams easier. I expect my workload to

decrease moving forward since the in-class

activities and quizzes are established and only

need moderate refining. Another important

consideration is class size. One of the great

benefits of the flipped model is being able to

interact with the students, but the number of

instructors/teaching assistants that are available to

assist the students during the learning activities

limits this. A major weakness of this project was

the absence of data to evaluate if the flipped model

improved student performance. While I do have

information about grades on exams and case

studies from previous semesters when the course

was not flipped, informed consent was not given for

past sections so data cannot be reported.

Additionally, the composition of the students from

semester to semester has great variability, which

greatly limits comparability.

References

1. EDUCAUSE Learning Initiative. Things you should

know about Flipped Classrooms. Educause

Learning Initiative website. Available at:

www.educause.edu. Published February 2013.

Accessed April 11, 2014.

2. Fitzpatrick M. Classroom lectures go digital. The

New York Times; June 24, 2012.

3. DesLauriers L, Schelew E, and Wieman C. Improved

learning in a large-enrollment physics class. Science

2011; 332: 862-864.

4. Walvoord BE, and Anderson VJ. Effective grading: A

tool for learning and assessment. San Francisco,

CA: Jossey-Bass; 1998.

5. Mazur E. Farewell, Lecture? Science 2009; 23: 5051.

6. Berrett D. How flipping the classroom can improve

the traditional lecture. Chronicle of Higher Education

website. Available at:

http://chronicle.com/article/How-Flipping-theClassroom/130857/. Published 2012. Accessed

April 12, 2014.

15 | NDEP-Line | Winter 2014

If Nutrition Is Your profession, Then Public

Policy Is Your Future?

Wendy Phillips, MS, RDN, CNSC, CLE, FAND

President, Virginia Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics

Angie Hasemann, MS, RDN, CSP

Dietetic Internship Director, University of Virginia Health System

wp4b@virginia.edu

434-982-2522

Public policy training for nutrition students

and interns

If nutrition is your profession then public policy is

your business. As dietetic students, interns, and

registered dietitian nutritionists (RDNs), we hear

this slogan frequently, yet so few actually

become involved in public policy at the

grassroots level. Only about 7% of members of

the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics

(abbreviated as the Academy) responded to the

Call to Action for the Treat and Reduce Obesity

Act, and less than 10% of state affiliate members

vote in state or national elections for board

positions of these organizations. Most state

affiliates of the Academy report that only three to

four percent of their members participate in the

annual Legislative Day held in the capitol of each

state. If we say public policy is our business, we

do a poor job of showing our business skills.

Barriers to involvement

Many describe hesitancy to become involved in

new activities as fear of the unknown, including

public policy. Students receiving primary

education in the United States are often required

to take a Civics class in eighth grade and

sometimes have refresher classes in high school

and possibly college. However, the information

may seem insignificant to them and their future

careers, and many students do not remember

specifics by the time they enter the workforce. In

addition, students may not complete their

internships or accept employment in the same

state (or even the same country!) as their primary

education, and, therefore, need to learn public

policy specific to the state in which they are now

living and working. Walking in to a legislators

office can be an intimidating task, especially if the

person does not comfortably understand the

structure of government or policies related to

nutrition and healthcare in their area.

Another reason dietitians report not becoming

involved in public policy is being unconvinced

that the rewards would be worth the time

invested. Due to the realities of healthcare

budgets, most dietitians do not have time built

into their daily activities at work to participate in

public policy, and even taking one day off to

attend state affiliate Legislative Days may prove

challenging, especially if the state capitol is a

long distance to travel. Low numbers of dietitians

responding to calls to action and organized

legislative activity may indicate that supervisors

arent fully supporting legislative activity by their

RDN staff and, furthermore, may not be setting

an example of being active in public policy.

Therefore, it is important to help dietitians

understand how public policy impacts their day to

day work, their patients, and their profession. In

addition, reducing the fear of the unknown

through mentoring is an effective way to increase

participation in public policy activities. Preparing

dietitians to enjoy and succeed in public policy

matters begins long before they make their way

into a legislators office and, preferably, long

before becoming a RDN.

Starting early

Just as dietetic students and interns are learning

medical nutrition therapy and foodservice

management, it is beneficial to learn the basics of

public policy during their education. A best

practice from the University of Virginia Health

System Dietetic Internship features a seasoned

RDN public policy leader hosting a Mock

General Assembly. In this creative activity,

interns learn about the legislative priorities

established by the Academy, and then draft mock

nutrition bills to be introduced in the mock

General Assembly (GA). They introduce the bills

16 | NDEP-Line | Winter 2014

into the mock Virginia House of Delegates, and

advocate for these bills, which they then debate.

As members of the mock subcommittees in the

House of Delegates or Senate, they ultimately

vote on the proposed bills, and present 2 final

choices to the mock Governor. The Governor

(usually impersonated by the Internship Director)

then approves one bill and the team of interns

who drafted that bill wins a prize. This lesson not

only shows how public policy can be fun and

relevant, it introduces the structure of the GA and

legislative process in a relaxed setting. This

makes the perfect practice session just before

the state affiliates Legislative Day at the state

capitol.

Making it easier/taking away the barriers

Mentoring

An informal poll of current and past board

members for the Virginia Academy of Nutrition

and Dietetics (VAND) stated the most important

factor for getting them involved in leadership

positions for the state affiliate or in public policy

activities was mentoring. Dietitians, nutrition

students, and interns were more likely to make

the first visit with an elected representative to

discuss nutrition-related public policy if they were

accompanied by a dietitian who was familiar with

the process. Anecdotal evidence supports that

witnessing an RDN skilled in public policy

casually converse with a legislator whom they

knew well helps to not only educate but, also,

inspire others. State capitols may be distant from

the dietitians hometown, and legislators are often

very busy when the GA is actually in session.

Therefore, it is helpful for the first visit to be

conducted in the legislators home district office

when the GA is not in session. This may also be

a less intimidating environment for someone new

to the experience.

These visits do not need to be heavily scripted or

focused on specific legislation. In fact, the first

meeting with a legislator should take place when

there is no nutrition-related legislation being

considered because this helps to establish a

relationship outside of the specific request to vote

for the legislation. This serves as a great

opportunity to introduce the dietetics field, the

path to becoming an RDN, and the patients or

clients helped by RDNs on a daily basis.

Providing a base understanding of the field and

the many roles an RDN can play will help

reinforce the importance of the profession and

how RDNs serve the constituents in the

legislators area. For someone new to public

policy, it may be helpful to provide a simple

notecard with talking points to cover, including

the number of dietitians in the state and

legislative district, the wide variety of fields in

which RDNs work, and a reminder to offer to be

expert reviewers for nutrition-related bills. The

message is simple, but helping to coach and

mentor others until they are comfortable is

essential to training future public policy leaders.

Making it personal

Above all, it is important to remember that politics

is still personal. While statistics about the impact

of obesity on chronic health diseases like

diabetes and cardiovascular disease are

important to have available, a story about a

patient who suffered from obesity and its

resultant diseases and was subsequently helped

by an RDN to improve their quality of life and

medical conditions will be more powerful. While

people may struggle to recall the statistics you

shared, they will remember the stories you tell.

Use these stories to paint a picture for the

legislator, just as you would for a friend or

colleague. People, including legislators, make

decisions with their emotional brain, not their

rational brain.1 It is important to help legislators

see the human connection in the nutrition-related

policy efforts for which we are advocating.

In addition to personal stories, a picture is worth

a thousand words. Bringing pictures of RDNs,

dietetic interns, and nutrition students working in

a variety of settings and with a variety of people,

such as pregnant women, children, elderly,

hospitalized, athletes, and other healthy people

can help legislators understand the magnitude of

impact that RDNs can have in the lives of their

constituents. These pictures can speak louder

than words when used on posters, websites, and

social media sites as well.2 Encouraging RDs,

students, and interns to begin capturing the work

they do in the community in photos early on in

the career will lend itself to more engaging career

portfolios, as well as more intriguing evidence

when advocating for the profession in the public

policy arena.

17 | NDEP-Line | Winter 2014

Practical (and easy!) steps to become

involved

Tell your story

Our legislators are elected by us, to represent us.

They care about their constituents as much as

we care about our patients and for the same

reason! Most RDNs become dietitians to make a

difference in the lives of patients. Most

legislators entered the profession because they

want to make a difference in their county, state,

and/or country. In the same way that dietitians

need to hear a patients story in order to help

him/her, the legislators need to hear how they

can help us. During the 2014 Lobby Day for the

Virginia Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, two

state legislators spoke to the dietitians and

interns in attendance. Both of these Delegates

stressed the importance of telling success stories

of dietitians working with patients.

Knowing what stories to tell and how to introduce

them can be challenging for someone who is new

to public policy. This is worth practicing on the

car ride to the legislators office or even at district

or state dietetic meetings. Asking fellow RDs

some pointed questions can help to guide this.

What do you love most about your job? Can you

tell me about a patient whose progress you were

most proud to be a part of? Have you had a

patient or client express appreciation to you

recently? What did he/she say?

Often, the story will come out without rehearsal.

Simply in talking to a person and mentioning

nutrition, they likely have a comment, question, or

story themselves. Whether it is that their neighbor

is an RDN, they want to know more about sports

nutrition, or theyve had their own weight loss

journey, listen. Use nutrition counseling skills to

engage and ask open-ended questions. Learn

more about the background of the story. This

may seem challenging, but training in

motivational interviewing often takes over, and it

becomes a conversation. Find ways in this

conversation to get to know the legislator better

and to emphasize the vital role RDNs play in

healthcare. Often, conversations with a legislator

have quite a few similarities to conversations with

clients or patients, just with a different but equally

important purpose.

By finding ways to tell stories and make public

policy personal, this intimidating topic can not

only be easier, but also more fun. Engage a few

colleagues to help mentor, and you are

guaranteed to have a great time at your

representatives home office, state Legislative

Day, or even on Capitol Hill. Do you have

creative ideas on how you make public policy

your business? Please share them with us at

vand.president@gmail.com.

References:

1. Damsio A. Descartes' Error: Emotion,

Reason, and the Human Brain. Putnam

Publishing; 1994.

2. Just a Handful of Social Media Comments

Can Grab the Attention of Congress, Study

Shows. CQ Roll Calls Website.

http://connectivity.cqrollcall.com/just-ahandful-of-social-media-comments-can-grabattention-of-congress-study-shows/. Updated

October 27, 2014. Accessed November 25,

2014.

Mark Your Calendars

Certificate of Training in Adult Weight

Management:

March 20-22, 2015, New Brunswick, NJ

June 4-6, 2015, New Orleans, LA

Certificate of Training in Childhood and

Adolescent Weight Management:

March 12-14, 2015, Charlotte, NC

Coding and Billing Webinar

Spring 2015: Upcoming NDEP Webinar on

Coding and Billing presented by Jessie Pavlinac

to provide directions on using the new

Academy Coding and Billing Handbook: A Guide

for Program Directors and Preceptors. More

information will be sent through the NDEP EML.

18 | NDEP-Line | Winter 2014

Best Practices in Food Systems

Management and Quantity Foods

Production

Jeanie Subach, EdD, RD, CSSD, LDN

Assistant Professor, Department of Nutrition

West Chester University of Pennsylvania

rsubach@wcupa.edu

610 436-2762

The May 2012 supplement of the Journal of the

Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics titled

Management Is a Multifaceted Component

Essential to the Skill Set of Successful Dietetics

Practitioners1 stresses the need for inclusion of the

development of managerial skills in didactic and

supervised practice curriculum for future

practitioners. The supplement explains the

inclusion should not be limited to foodservice

management courses and experience, rather

woven throughout all parts of curricula and

practices. It further discusses the need to remove

the question of Are you management or clinical

from the conversations of the dietetic profession,

stating Management should be inculcated in the

members of our profession in a variety of

contexts.1

Most dietetic educators would agree that food

systems management and quantity food production

are not the most popular courses in the didactic

curriculum. As faculty in a DPG program, teaching

both Quantity Foods Production and Food Systems

and Nutrition Management, I am faced with the task

of engaging students in the concepts of both

courses. The challenge lays in increasing the

understanding of the importance of the role of the

registered dietitian in food systems management

and quantity foods production.

The initial assignment given to students in the

Quantity Food Production class at West Chester

University of Pennsylvania is the completion of a

self-assessment used to survey their experience

and interest of the food service industry. The final

question of the assessment asks the likelihood that

they will pursue a career in food service post

baccalaureate. The majority of the responses from

the 130+ students indicated a preference to pursue

a career that is more clinical or communityoriented. I respond each year by sharing the

journal supplement, reinforcing that the success in

clinical and community nutrition cannot be achieved

without quality quantity food production, which

cannot be achieved without strong managerial

skills. A goal of the course is to dispel the

perception of mean foodservice directors and lunch

ladies in hair nets, educating on the value, scope,

and depth of the area of management and food

service as a support system to clinical and

community endeavors/operations.

As a compliment to course content, students plan

and execute a quantity foods production project.

Using the concepts of the systems theory model,

students plan the menu and are assigned different

task as part of management and production teams.

The audiences of the productions are organizations

within and outside the University, which adds a

service learning component to the course. At the

completion of the events, students write a reflection

paper and conduct a production analysis in class.

One function was the production of a dinner meal

for 165 persons. Meal recipients were students and

families of the Universitys Adapted Physical

Education program (APE). The program provides

physical education to children ages 6-18 with

intellectual and developmental disabilities. The gym

of the College of Health Sciences served as the

dining room, and the foods lab was the quantity

foods kitchen. The less than ideal setting posed

many obstacles requiring the students to work as a

team and use their problem solving abilities.

The menu was designed, distributed, and returned

prior to the event. Students executed all aspects of

procurement, production, and service, upholding

their obligations as ServSafe Managers.

Purchasing and production modifications were

made to accommodate allergens and special

feeding needs. At the completion of the event,

customer and employee satisfaction and financial

accountably, all desired outputs of the Food

Systems Model, were all successfully obtained.

19 | NDEP-Line | Winter 2014

While this may seem like a typical quantity food

class production, the event was actually a tipping

point, allowing students to view foodservice through

a different lens. At the end of the event, the

director of the APE program called the nutrition

students together informing them of a

breakthrough that occurred during service. An 11year-old boy with autism took a bite of an apple for

the first time in his life. His mother, coach, and

program director cried at the sight. The APE

director told them that through the design of the

menu, service, and positive interaction between the

nutrition majors, students, and families, that healthy

food was served and accepted in a safe, friendly

environment. The director explained that this

enabled the child to feel safe and comfortable

enough to do something he had never done before.

She told them they did more than just serve food,

that they made a difference in the life of a young

boy with autism. The next day in class discussion,

although pleased with the successful execution of

the event, the students were more excited with

making a difference in the life of a child with autism.

The statement made at the start of the semester

that success in clinical and community nutrition

cannot be achieved without quality quantity food

production was repeated, and this time the students

understood.

Exposing students to various populations and food

services experiences allows them to see first-hand

the importance of food systems management and

foodservice as a vehicle to provide healthy food to

the public in the quest of decreasing incidences of

obesity and other diet-related chronic diseases.

References

1. Canter, DD, Sauer, KL, Shanklin, CW.

Management Is a Multifaceted Component

Essential to the Skill Set of Successful

Dietetics Practitioners. J Acad Nutr Diet,

2012, 112(5), S5.

Happy Holidays

From Your

NDEP Council

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (890)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (587)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (344)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (119)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2219)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- A Strategic Management PaperDokumen7 halamanA Strategic Management PaperKarll Brendon SalubreBelum ada peringkat

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- American Literature TimelineDokumen2 halamanAmerican Literature TimelineJoanna Dandasan100% (1)

- 05 Askeland ChapDokumen10 halaman05 Askeland ChapWeihanZhang100% (1)

- VV016042 Service Manual OS4 PDFDokumen141 halamanVV016042 Service Manual OS4 PDFCamilo Andres Uribe Lopez100% (1)

- Adhd Nutrition Considerations ChecklistDokumen1 halamanAdhd Nutrition Considerations Checklistapi-235820714Belum ada peringkat

- Adhdreferences 2016Dokumen4 halamanAdhdreferences 2016api-235820714Belum ada peringkat

- Nutrition Screening Acute Care Setting Newsletter Winter 2017 Phillips DoleyDokumen8 halamanNutrition Screening Acute Care Setting Newsletter Winter 2017 Phillips Doleyapi-235820714Belum ada peringkat

- Fnce 2017 LTC Productivity Benchmarks AbstractDokumen1 halamanFnce 2017 LTC Productivity Benchmarks Abstractapi-235820714Belum ada peringkat

- Granting Owps To Rdns Can Decrease Costs Andj Phillips DoleyDokumen8 halamanGranting Owps To Rdns Can Decrease Costs Andj Phillips Doleyapi-235820714Belum ada peringkat

- Western Hemisphere ProfileDokumen1 halamanWestern Hemisphere Profileapi-235820714Belum ada peringkat

- Beastarsept 2016Dokumen1 halamanBeastarsept 2016api-235820714Belum ada peringkat

- 2201 October p1 DK 13 17Dokumen5 halaman2201 October p1 DK 13 17api-235820714Belum ada peringkat

- Pine View Invitational Deca 2nd Place Jan 2016Dokumen1 halamanPine View Invitational Deca 2nd Place Jan 2016api-235820714Belum ada peringkat

- Braden Scale Jan 2017 JandDokumen6 halamanBraden Scale Jan 2017 Jandapi-235820714Belum ada peringkat