Organizational Communication Doctor Nurse Relationship

Diunggah oleh

api-284740755Deskripsi Asli:

Judul Asli

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Organizational Communication Doctor Nurse Relationship

Diunggah oleh

api-284740755Hak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Challenges

and Implications of the Doctor/Nurse Relationship

The Challenges and Implications of the Doctor/Nurse Relationship

Bryan A. Aungst

Juniata College

Challenges and Implications of the Doctor/Nurse Relationship

Introduction

The

health

care

industry

is

heavily

regulated.

Because

constant

strains

on

funds,

government

regulations,

and

limited

resources

are

often

coupled

with

ample

opportunity

for

lawsuits

and

life-altering

or

life-threatening

mistakes,

the

organizational

structure

of

a

health

care

setting

is

often

hierarchical

in

nature,

and

very

rigid.

In

this

healthcare

setting

however,

the

interactions

between

doctors

and

nurses

can

often

have

implications

beyond

the

initial

interaction.

The

relationship

between

the

superior

and

subordinate

in

any

number

of

organizations

is

fairly

well

studied.

Each

industry

and

each

organization

cannot

exist

without

some

form

of

interaction

between

the

superior

and

the

subordinate.

Individual

companies

tend

to

have

their

own

rules,

regulations,

and

norms

for

these

interactions,

but

larger

trends

found

across

most

health

care

facilities

tend

to

emerge.

These

trends

will

be

discussed

later

in

this

paper.

Researchers report an important link between perceived openness of

communication

and

reciprocity

(the

extent

to

which

the

superior

and

superordinate

agree

on

their

level

of

interdependence)

and

the

important

role

they

play

on

the

status

of

a

given

health

care

setting

(Coombs,

2003;

Frankel

&

Stein,

1999;

Frankel,

Krupat,

&

Stein,

2005;

Hughes,

2008;

Lindeke

&

Sieckart,

2005;

Lingard,

Reznick,

Espin,

Regehr,

&

DeVita,

2002;

Manojlovich,

2005;

Manojlovich

&

DeCicco,

2007;

Sutcliffe,

Lewton,

&

Rosenthal,

2004;

Svensson,

1996).

Because

of

the

harried

nature

of

health

care

and

the

necessary

hierarchy,

there

are

often

challenges,

such

as

limited

time

permitted

for

interactions

or

unclear

directions

being

given,

that

strain

the

superior/subordinate

relationship.

Challenges and Implications of the Doctor/Nurse Relationship

In the following pages I will discuss the challenges presented by the

superior/subordinate relationship in a health care setting. Topics covered include the

importance of communication between these parties, and methods of assessment and

suggestions to improve this communication, how government regulation both protects and

puts a strain on health care, and how it attempts to reform the superior/subordinate

relationship that currently exists in most hospitals and doctors offices. I will also address

implications of these superior/subordinate relationships, and how improving

communication can improve health care on a macro level, therefore arguing that

implementing training to improve communication between doctors and nurses can benefit

hospitals and other health care settings economically.

Before I discuss the literature, it is important to define the terms I will be using.

When I talk about just health care, I am talking about the industry as a whole, and

generalized to U.S. American health care. When the term health care setting is used, I am

generally referring to hospitals, doctors offices, outpatient centers, and the like. From here

on out the abbreviation HCS is used as a generalization for health care setting.

In HCSs, due to the complex nature of the system and the rigid hierarchy, there are

many superiors and many subordinates, and often a person is both. A doctor may be a

superior to an intern, but a subordinate to the head of his or her department. For the sake

of simplifying my writing, it should be assumed that superior in this paper should be

generalized as doctor, and that subordinate should be generalized as nurse or intern

(resident).

Challenges and Implications of the Doctor/Nurse Relationship

The Doctor-Nurse Game

When it comes to working in HCSs, cases can often be life or death, but many times

they are not. The role of nursing has been changing greatly in recent years due to financial

strains on the health care system. Nurses are being asked to take on more and more

primary care roles, creating a time of uncertainty (Williams & Sibbald, 1999, pp. 737).

This phrase describes the dissonance between nurses responsibilities and place in the

hierarchy of their HCS (Williams & Sibbald, 1999). Despite the fact that nurses are being

asked to perform more duties and make more decisions, some scholars argue that doctors

often get the final say (Coombs, 2003; Svensson, 1996).

With nurses being more involved with patients interpersonally, they are more

equipped to make calls about medical decisions that are in line with patients wishes.

However, referring once again to the hierarchical structure of health care organizations, we

see that doctors have final say. From this frustrating trend over the years, we see the

emergence of a phenomenon known as the Doctor-Nurse game (Hughes, 2008).

Hughes (2008) describes the Doctor-Nurse game as an interaction or series of

interactions in which the nurse must appear to be subordinate to the doctor while offering

nonverbal cues and the like to manipulate the doctor or to affect a diagnosis. These games

are often played around decisions such as deciding whether or not a patient is in need of

hospitalization or which course of treatment should be taken for specific patients (Coombs,

2003).

Hughes (2008) and Svensson (1996) suggest however that the Doctor-Nurse game

is not a normal practice in current medicine. Svensson (1996) argues that nurses and

doctors can and do negotiate (i.e. communicate about duties, treatments, and the like) and

Challenges and Implications of the Doctor/Nurse Relationship

this

causes

change

in

the

power

hierarchy

seen

in

HCSs.

Hughes

(2008)

also

states

that

a

trend

of

collaboration

in

forming

diagnoses

is

emerging

in

industrialized

health

care

settings.

This

makes

the

idea

of

power

interesting

to

consider,

because

in

Hughes

and

Svenssons

views,

more

power

is

shifting

to

the

nurses.

Amidst

the

conflicting

messages

floating

around

regarding

the

state

Doctor-Nurse

game,

it

could

be

said

that

the

doctor

is

out

on

this

subject.

There

is

no

one

clear

answer,

but

I

believe

that

remnants

of

this

game

do

indeed

still

exist,

and

may

be

found

more

often

depending

on

what

geographic

area

one

is

looking

in

for

them.

One

of

the

first

things

to

consider

when

observing

how

doctors

and

nurses

interact

in

HCSs

is

how

they

were

trained.

The

type

of

training

that

doctors

receive

for

dealing

with

patients

and

others

is

somewhat

different

from

the

training

that

nurses

receive

(Lindeke

&

Sieckart,

2005).

Nurses

often

spend

more

one

on

one

time

with

patients,

and

thus

tend

to

receive

more

training

and

practice

in

interpersonal

communication

when

it

comes

to

dealing

with

patients

(Hunter,

1996).

According

to

Frankel,

Krupat,

and

Stein

(2005),

when

one

receives

training

in

communication

skills

in

one

area,

improvement

can

often

be

seen

in

other

interactions.

Knowing

this,

it

can

be

assumed

that

nurses

training

in

interpersonal

skills

with

patients

often

help

them

in

interacting

with

colleagues

and

superiors.

Miscommunication

between

doctors

and

nurses

is

often

the

main

cause

of

medicine-

based

and

non-operational

treatment

mistakes

(Sutcliffe,

Lewton,

&

Rosenthal,

2004).

With

that

as

a

known

fact,

improving

this

communication

should

be

a

priority

in

most

HCSs.

A

main

focus

should

specifically

be

on

interpersonal

communication

skills.

According

to

Duffy

et

al.

(1999):

Challenges and Implications of the Doctor/Nurse Relationship

While

communication

skills

are

the

performance

of

specific

tasks

and

behaviors

by

an

individual,

interpersonal

skills

are

inherently

relational

and

process

oriented.

Interpersonal

skills

focus

on

the

effect

of

communication

on

another

person.

(p.

497)

Assessing

Communication

There

are

a

number

of

ways

to

assess

communication

skills

of

doctors

and

nurses.

One

particularly

useful

method

is

patient

questionnaires

and

surveys.

The

patient

is

often

the

best

judge

of

the

interpersonal

skills

of

these

professionals

(Duffy

et

al.,

2004).

Another

useful

method

is

the

use

of

checklists

to

guide

doctor

and

nurse

behaviors

and

observation

by

a

professional

trained

in

communication

theory

can

help

to

assess

the

ability

of

a

doctor

or

nurse

in

their

interpersonal

skills

with

patients

(Duffy

et

al.,

2004).

These

methods

could

easily

be

adapted

to

view

how

doctors

and

nurses

interact

with

each

other.

Improving

Communication

Once

ample

information

has

been

gathered

about

communication

ability

(strengths

and

deficiencies

alike),

a

plan

can

be

developed

to

improve

communication

skills.

Frankel,

Krupat,

and

Stein

(2005)

suggest

that

the

average

U.S.

physician

conducts

between

140,000

and

160,000

medical

interviews

in

his

or

her

life,

and

this

can

lead

to

burnout

and

lower

quality

communication.

Large

California-based

health

care

provider

Kaiser

Permanente

utilized

a

method

known

as

the

Four

Habits

Model

in

order

to

aid

clinicians

in

learning

and

improving

important

basic

communication

skills

quickly

and

efficiently

(Frankel,

Krupat,

&

Stein,

2005).

Upon

following

up

with

patient

surveys,

Kaiser

Permanente

verified

that

the

use

of

the

Four

Habits

Model

did

indeed

help

improve

the

communication

skills

of

the

clinicians

within

the

organization

(Frankel,

Krupat,

&

Stein,

2005).

Based

on

their

success,

Challenges and Implications of the Doctor/Nurse Relationship

the

Four

Habits

Model

has

picked

up

a

bit

of

steam

and

is

being

used

more

often

to

help

improve

these

skills.

The Four Habits Model (Table 1 in appendix) discusses the four main habits

clinicians

should

exhibit

while

conducting

medical

interviews.

The

four

habits

are:

Invest

in

the

Beginning,

Elicit

the

Patients

perspective,

Demonstrate

Empathy,

and

Invest

in

the

End

(Frankel,

Krupat,

&

Stein,

2005).

The

model

outlines

the

skills

associated

with

each

habit,

lists

techniques

and

gives

examples

of

them,

and

outlines

the

payoff

from

exhibiting

each

habit.

This

can

be

beneficial

especially

in

training

new

interns

or

residents,

as

communication

in

everyday

interactions

and

settings

such

as

the

Operating

Room

help

to

socialize

the

novices,

who

may

have

negative

opinions

of

them

formed

from

unsatisfactory

communication

with

superiors

(Lingard,

Reznick,

Espin,

Regehr,

&

DeVito,

2002).

Implications

Having

stronger

interpersonal

skills

and

better

communication

between

doctors

and

nurses

has

a

number

of

important

implications.

One

of

the

timeliest

implications

stems

from

government

pressure

on

the

health

care

system.

The

U.S.

government

expectation

of

health

care

management

and

real

life

practice

are

in

a

state

of

dissonance

(Hunter,

1996).

The

government

wants

a

more

flexible

team-oriented

approach

to

health

care,

but

according

to

Coombs

(2003),

this

is

not

the

common

practice

yet.

Strengthening

interpersonal

communication

will

aid

in

shifting

to

this

more

team-based

system.

Another

important

implication

of

a

more

reciprocal

relationship

between

doctors

and

nurses,

with

greater

perceived

open

communication,

is

the

improvement

of

job

satisfaction

for

nurses

(Frankel

&

Stein,

1999;

Frankel,

Krupat,

&

Stein,

2005;

Hunter,

1996;

Manjojlovich,

2005;

Manjojlovich

&

DeCicco,

2008;

Mayfield,

Mayfield,

&

Kopf,

1998;

Challenges and Implications of the Doctor/Nurse Relationship

Williams

&

Sibbald,

1999).

While

environment

and

structural

empowerment

play

a

role

in

job

satisfaction

for

nurses,

nurses

also

highly

value

open

communication

with

the

doctors

they

work

with,

and

the

relationship

between

their

perceived

quality

of

communication

and

their

job

satisfaction

is

directly

proportional

(Manjojlovich,

2005).

Adding

to

that,

in

most

settings,

when

nurses

job

satisfaction

was

higher,

patient

outcomes

were

better

and

mortality

rates

were

lower

(Manjojlovich,

2005).

The

correlation

between

job

satisfaction

and

patient

outcomes

holds

true

in

all

medical

environments

other

than

Intensive

Care

Units

(ICU).

Job

satisfaction

does

not

necessarily

affect

patient

mortality

in

ICUs

(Manjojlovich

&

DeCicco,

2007).

This

is

perhaps

due

to

the

nature

of

the

patients

that

come

through

the

ICU.

There

is

a

higher

chance

for

these

patients

to

die

in

general

than

for

patients

in

other

floors

of

hospitals.

Another

important

trend

did

emerge

however.

In

the

ICUs,

a

correlation

was

found

between

nurses

job

satisfaction

and

a

lower

risk

of

nurse-assessed

medication

errors

(Manjojlovich

&

DeCicco,

2007).

When

nurses

were

happier

with

their

jobs,

they

made

less

medication-

centered

errors.

This

again,

is

linked

back

to

perceived

reciprocity

and

openness

of

communication

that

nurses

have

with

doctors.

Other

studies

had

similar

findings.

Between

44,000

and

98,000

people

die

in

hospitals

in

the

U.S.

annually

due

to

errors,

and

these

errors

often

are

results

of

miscommunication

(Sutcliffe,

Lewton,

&

Rosenthal,

2004).

In

one

study,

Sutcliffe,

Lewton,

and

Rosenthal

(2004)

stated:

The

occurrence

of

everyday

medical

mishaps

in

this

study

is

associated

with

faulty

communication;

but,

poor

communication

is

not

simply

the

result

of

poor

transmission

or

exchange

of

information.

Communication

failures

are

far

more

Challenges and Implications of the Doctor/Nurse Relationship

complex and relate to hierarchical differences, concerns with upward influence,

conflicting roles and role ambiguity, and interpersonal power and conflict. (p. 186)

Lowering the number of patient mortalities and creating better patient outcomes

have

greater

benefits

than

those

received

by

the

individual

patients.

Patients

who

are

treated

for

their

condition

and

treated

well

in

the

process

are

less

likely

to

pursue

lawsuits

(Manjojlovich,

2005).

Along

with

that,

nurses

that

are

satisfied

with

their

jobs

and

making

fewer

errors

tend

to

use

resources

(including

time)

more

efficiently

(Sutclifee,

Lewton,

and

Rosenthal,

2004).

Both

of

these

are

substantial

economic

benefits

to

HCSs.

Conclusion

The

relationship

between

doctors

and

nurses,

superiors

and

subordinates

is

complex.

A

number

of

organizational

barriers

and

government

pressure

can

put

strain

on

this

relationship,

as

outlined

earlier.

Open,

reciprocal

communication

that

utilizes

strong

interpersonal

skills

can

help

to

bypass

these

barriers.

When

nurses

feel

unable

to

openly

communicate

with

doctors,

they

may

resort

to

methods

of

manipulation

in

order

to

get

doctors

to

see

their

point

of

view.

However, if HCSs, and the health care industry in general, are willing to step back

and

observe

the

ways

in

which

communication

between

superiors

and

subordinates

take

place,

they

can

implement

programs

and

training

that

can

improve

interpersonal

skills.

The

benefits

of

improving

these

skills

are

many,

as

Ive

shown

here.

Not

only

do

patients

fare

better,

but

also

there

are

economic

benefits

to

be

had,

and

a

feasible

decrease

in

lawsuits.

In the literature, scholars speculate about the direction that the health care industry

was

headed.

In

the

U.S.,

the

government

is

pushing

for

a

teams

approach

to

health

care,

which

in

some

ways

could

be

very

beneficial.

However,

with

nurses

and

doctors

working

Challenges and Implications of the Doctor/Nurse Relationship

10

together on teams, the importance of interpersonal communication skills becomes even

greater.

The challenges of the doctor/nurse relationship in the current health care

atmosphere

are

great,

but

still

navigable.

If

health

care

in

the

U.S.

truly

is

in

a

time

of

uncertainty,

than

the

challenges

of

this

relationship

will

become

greater

as

we

transition

into

a

new

way

of

doing

things.

And

yet

it

is

the

implications

of

these

relationships

that

should

receive

the

most

focus.

When

the

involved

parties

perceive

the

relationship

as

healthy,

everyone

benefits.

Challenges and Implications of the Doctor/Nurse Relationship

11

Bibliography

ABIM

Medical

Professionalism

Project.

(2002)

Medical

professionalism

in

the

new

millennium:

a

physician

charter.

Annals

of

Internal

Medicine,

136.

Retrieved

from

http://gme.cchange.com/portals/7/media/ProfessionalismArticle.pdf.

Coombs,

M.

(2003)

Power

and

conflict

in

intensive

care

clinical

decision

making.

Intensive

and

Critical

Care

Nursing,

19.

Retrieved

from

http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0964339703000405.

Duffy,

D.,

Gordon,

G.

H.,

Whelan,

G.,

Cole-Kelly,

K.,

Frankel,

R.,

&

All

Participants

in

the

American

Academy

on

Physician

and

Patients

Conference

on

Education

and

Evaluation

of

Competence

in

Communication

and

Interpersonal

Skills.

(2004)

Assessing

Competence

in

Communication

and

Interpersonal

Skills:

The

Kalamazoo

II

Report.

Academic

Medicine,

79.

Retrieved

from

http://journals.lww.com/academicmedicine/Abstract/2004/06000/Assessing_Co

mpetence_in_Communication_and.2.aspx.

Frankel,

R.

M.,

&

Stein,

T.

(1999)

Getting

the

Most

out

of

the

Clinical

Encounter:

The

Four

Habits

Model.

The

Permanente

Journal,

3.

Retrieved

from

http://xnet.kp.org/permanentejournal/fall99pj/habits.pdf.

Frankel,

R.

M.,

Krupat,

E.,

&

Stein,

T.

(2005)

Enhancing

clinician

communication

skills

in

a

large

healthcare

organization:

A

longitudinal

case

study.

Patient

Education

and

Counseling,

58.

Retrieved

from

http://pdn.sciencedirect.com/science?_ob=MiamiImageURL&_cid=271173&_user=1

08064&_pii=S0738399105000133&_check=y&_origin=article&_zone=toolbar&_cov

erDate=31-Jul-2005&view=c&originContentFamily=serial&wchp=dGLbVlV-

zSkzS&md5=730b690e73f9a56905c6879150042dcd/1-s2.0-S0738399105000133-

main.pdf.

Hughes,

D.

(2008)

When

nurse

knows

best:

some

aspects

of

nurse/doctor

interaction

in

a

casualty

department.

Sociology

of

Health

&

Illness,

10.

Retrieved

from

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1467-9566.ep11340102/pdf.

Hunter,

D.

J.

(1996)

The

changing

roles

of

health

care

personnel

in

health

and

health

care

management.

Social

Science

&

Medicine,

43.

Retrieved

from

http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/0277953696001256.

Lindeke,

L.

L.,

&

Sieckart,

A.

M.

(2005)

Nurse-Physician

workplace

collaboration.

Online

Journal

of

Issues

in

Nursing,

10.

Retrieved

from

http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/499268.

Challenges and Implications of the Doctor/Nurse Relationship

12

Lingard,

L.,

Reznick,

R.,

Espin,

S.,

Regehr,

G.,

&

DeVito,

I.

(2002)

Team

Communications

in

the

Operating

Room:

Talk

Patterns,

Sites

of

Tension,

and

Implications

for

Novices.

Academic

Medicine,

77.

Retrieved

from

http://journals.lww.com/academicmedicine/Fulltext/2002/03000/Team_Commun

ications_in_the_Operating_Room__Talk.13.aspx.

Manojlovich,

M.

(2005)

Linking

the

Practice

Environment

to

Nurses

Job

Satisfaction

Through

Nurse-Physician

Communication.

Journal

of

Nursing

Scholarship,

37.

Retrieved

from

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1547-

5069.2005.00063.x/pdf.

Manjojlovich,

M.,

&

DeCicco,

B.

(2007)

Healthy

Work

Environments,

Nurse-Physician

Communication,

and

Patients

Outcomes.

Journal

of

Critical

Care,

16.

Retrieved

from

http://ajcc.aacnjournals.org/content/16/6/536.full.

Mayfield,

J.

R.,

Mayfield,

M.

R.,

&

Kopf,

J.

(1998)

The

effects

of

leader

motivating

language

on

subordinate

performance

and

satisfaction.

Human

Resource

Management,

37.

Retrieved

from

http://www.uthscsa.edu/gme/documents/EffectsofLeaderMotivatingLanguage.pdf.

Sutcliffe,

K.

M.,

Lewton,

E.,

&

Rosenthal,

M.

(2004)

Communication

Failures:

An

Insidious

Contributor

to

Medical

Mishaps.

Academic

Medicine,

79.

Retrieved

from

http://journals.lww.com/academicmedicine/Fulltext/2004/02000/Communication

_Failures__An_Insidious_Contributor.19.aspx.

Svensson,

R.

(1996)

The

interplay

between

doctors

and

nurses

a

negotiated

order

perspective.

Sociology

of

Health

&

Illness,

18.

Retrieved

from

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1467-9566.ep10934735/pdf

Williams,

A.

&

Sibbald,

B.

(1999)

Changing

roles

and

identities

in

primary

health

care:

exploring

a

culture

of

uncertainty.

Journal

of

Advanced

Nursing,

29.

Retrieved

from

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1046/j.1365-2648.1999.00946.x/abstract.

Challenges and Implications of the Doctor/Nurse Relationship

Appendix

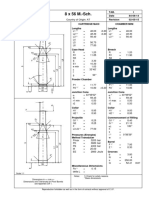

Table 1

13

Challenges and Implications of the Doctor/Nurse Relationship

14

http://www.google.com/imgres?um=1&hl=en&safe=off&sa=N&biw=1258&bih=608&tbm=isch

&tbnid=U4PBvp6pTQxAmM:&imgrefurl=http://xnet.kp.org/permanentejournal/Fall07/c

ommunication_skills.html&docid=QYFWeQblnyGPPM&imgurl=http://xnet.kp.org/perm

anentejournal/Fall07/F07/Assets/Images/CSIFig1_34184/CSIFig1.jpg&w=572&h=736&

ei=uQdsT8TPE8rq0gGu4PDoBg&zoom=1&iact=hc&vpx=249&vpy=118&dur=971&ho

vh=255&hovw=198&tx=123&ty=157&sig=108572509709806279782&page=1&tbnh=1

32&tbnw=103&start=0&ndsp=19&ved=1t:429,r:1,s:0

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5794)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (895)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (400)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (74)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (344)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)

- Vendor Registration FormDokumen4 halamanVendor Registration FormhiringBelum ada peringkat

- Investigation Data FormDokumen1 halamanInvestigation Data Formnildin danaBelum ada peringkat

- Tec066 6700 PDFDokumen2 halamanTec066 6700 PDFExclusivo VIPBelum ada peringkat

- Bharti Airtel Strategy FinalDokumen39 halamanBharti Airtel Strategy FinalniksforloveuBelum ada peringkat

- Flight Data Recorder Rule ChangeDokumen7 halamanFlight Data Recorder Rule ChangeIgnacio ZupaBelum ada peringkat

- BAMDokumen111 halamanBAMnageswara_mutyalaBelum ada peringkat

- Dependent ClauseDokumen28 halamanDependent ClauseAndi Febryan RamadhaniBelum ada peringkat

- Joomag 2020 06 12 27485398153Dokumen2 halamanJoomag 2020 06 12 27485398153Vincent Deodath Bang'araBelum ada peringkat

- Extraction of Mangiferin From Mangifera Indica L. LeavesDokumen7 halamanExtraction of Mangiferin From Mangifera Indica L. LeavesDaniel BartoloBelum ada peringkat

- 3) Uses and Gratification: 1) The Hypodermic Needle ModelDokumen5 halaman3) Uses and Gratification: 1) The Hypodermic Needle ModelMarikaMcCambridgeBelum ada peringkat

- Present Tenses ExercisesDokumen4 halamanPresent Tenses Exercisesmonkeynotes100% (1)

- Visi RuleDokumen6 halamanVisi RuleBruce HerreraBelum ada peringkat

- PRESENTACIÒN EN POWER POINT Futuro SimpleDokumen5 halamanPRESENTACIÒN EN POWER POINT Futuro SimpleDiego BenítezBelum ada peringkat

- 1KHW001492de Tuning of ETL600 TX RF Filter E5TXDokumen7 halaman1KHW001492de Tuning of ETL600 TX RF Filter E5TXSalvador FayssalBelum ada peringkat

- Communication Skill - Time ManagementDokumen18 halamanCommunication Skill - Time ManagementChấn NguyễnBelum ada peringkat

- Aharonov-Bohm Effect WebDokumen5 halamanAharonov-Bohm Effect Webatactoulis1308Belum ada peringkat

- Subeeka Akbar Advance NutritionDokumen11 halamanSubeeka Akbar Advance NutritionSubeeka AkbarBelum ada peringkat

- Brain Injury Patients Have A Place To Be Themselves: WHY WHYDokumen24 halamanBrain Injury Patients Have A Place To Be Themselves: WHY WHYDonna S. SeayBelum ada peringkat

- Pediatric Fever of Unknown Origin: Educational GapDokumen14 halamanPediatric Fever of Unknown Origin: Educational GapPiegl-Gulácsy VeraBelum ada peringkat

- EC 2012 With SolutionsDokumen50 halamanEC 2012 With Solutionsprabhjot singh1Belum ada peringkat

- The One With The ThumbDokumen4 halamanThe One With The Thumbnoelia20_09Belum ada peringkat

- An Enhanced Radio Network Planning Methodology For GSM-R CommunicationsDokumen4 halamanAn Enhanced Radio Network Planning Methodology For GSM-R CommunicationsNuno CotaBelum ada peringkat

- 8 X 56 M.-SCH.: Country of Origin: ATDokumen1 halaman8 X 56 M.-SCH.: Country of Origin: ATMohammed SirelkhatimBelum ada peringkat

- DBM Uv W ChartDokumen2 halamanDBM Uv W ChartEddie FastBelum ada peringkat

- Previews 1633186 PreDokumen11 halamanPreviews 1633186 PreDavid MorenoBelum ada peringkat

- Solutions DPP 2Dokumen3 halamanSolutions DPP 2Tech. VideciousBelum ada peringkat

- 1Dokumen2 halaman1TrầnLanBelum ada peringkat

- EP07 Measuring Coefficient of Viscosity of Castor OilDokumen2 halamanEP07 Measuring Coefficient of Viscosity of Castor OilKw ChanBelum ada peringkat

- MEMORANDUM OF AGREEMENT DraftsDokumen3 halamanMEMORANDUM OF AGREEMENT DraftsRichard Colunga80% (5)

- Kiraan Supply Mesin AutomotifDokumen6 halamanKiraan Supply Mesin Automotifjamali sadatBelum ada peringkat