Small Concrete Ornaments

Diunggah oleh

Andry HarmonyHak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Small Concrete Ornaments

Diunggah oleh

Andry HarmonyHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Making small garden ornaments

in concrete

Concrete is durable and relatively cheap and is therefore

suitable for making small garden ornaments. (By small we

mean weighing not more than about 40 kg - something that

one person can lift. The techniques described in this leaflet

can also be used for large castings but the process is more

complex and lifting devices are needed.)

Rubber moulds can be used for virtually any shape, even

with undercuts that would prevent the removal of a rigid

mould (see Figure 1). Although mould-making rubber is

expensive, a mould can give many satisfactory castings. The

making of a rubber mould involves many steps but careful

attention to detail will ensure a successful result.

The aim of this leaflet is to explain how to make a rubber

mould and cast concrete in it.

This leaflet describes:

Equipment and materials

Preparing the pattern

Making the mould and preparing it for casting

Casting, including demoulding, repairs and curing

Colouring the casting

These shapes prevent removal of the mould

Mould

Mould

Materials

Casting

Figure 1: Undercut shapes prevent removal of a rigid

mould

1. Equipment and materials

Equipment

Plastic mixing bowls of various sizes

Spatulas:

- A putty knife with the corners of the blade rounded

- A plasterers small tool with the handle straightened

(use an acetylene flame) and the corners of the

blades rounded

- A dentists spatula - ask your dentist where to buy

one or make a spatula by grinding (cool frequently to

prevent the steel from softening) an old screwdriver

to form a thin blade about 7 mm wide by 25 mm long

on a neck about 2 mm wide

Spade for mixing concrete - a bricklayers trowel with

the handle straightened and the blade cut off square

and the corners rounded

1 litre measuring jug

Small (15 mm) paint brush

Felt-tip pen with waterproof ink

Wooden dowel rods: 15 mm and 5 mm in diameter

Plastic sheeting, eg garbage bags

Old cloths

Bonding liquid

Polyurethane varnish

16 mm chipboard or wooden planks for base and mould

6 mm plywood for walls

Petroleum jelly

Mineral turpentine

Shellac dissolved in methylated spirits (200 g in 1 litre)

Cement complying with SANS 50197-1

Concrete sand, eg crusher or river sand

Concrete stone, size 6,7 or 9,5 mm

Water

Plaster of Paris - the standard grade is adequate

Synthetic modelling clay (Plasticine) - obtainable from

toy shops

Modelling wax (microcrystalline wax, which is like the

wax used to coat Gouda cheese)

Mould-making silicone rubber

White portland cement (for small repairs)

Polymer emulsion - acrylic or styrene butadiene

Colouring materials if needed (see section 9)

2. The pattern

The method described below consists essentially of making

a negative impression of a rigid solid object, and then filling

this negative shape with fresh concrete. The solid object we

start with is called a pattern. If you can, you may want to

sculpt your own pattern in, for example, wood or plaster of

Paris. Or you can use an existing object as a pattern.

If the pattern is made of an absorbent material such as

plaster of Paris, allow it to dry completely and apply two

coats of bonding liquid to strengthen the surface and then

two coats of polyurethane varnish to seal the surface.

Pattern

Fix a temporary wooden base to the pattern. The base will

form the mould for the ends of the liner and jacket.

The mould can be made in one of two ways:

The jacket-first method

The liner-first method

The jacket-first method has the advantage that the thickness

and shape of the outer surface of the rubber can be well

controlled. The advantage of the liner-first method is that the

use of less rubber compound may be possible.

Rubber liner

Rubber liner

Correct

Incorrect - liner will

bind at points B

Figure 3: Making provision for separating the rubber

liner and jacket of a mould

to a milky consistence with mineral turpentine (white

spirits). Release agent can be applied with a small paint

brush, making sure to remove any excess in corners,

etc.

3. Making the mould

The complete mould consists of a rubber liner and a

concrete jacket as shown diagrammatically in Figure 2. The

purpose of the jacket is to ensure that the rubber liner keeps

its shape while the concrete is being cast in it. (If only a few

castings are to be done, the jacket may be made of plaster

of Paris instead of concrete.)

Decide on the positions of the mould joints by imagining

how the individual pieces of the mould will be removed

from the pattern and the casting. For simple shapes, the

mould should consist of two pieces of roughly the same

size. Where possible mould joints should coincide with

sharp edges or raised ridges on the pattern. (On a head, for

example, the joint should run along the edge of the ear

rather than in front of or behind the ear.) Mark the joint

positions on the pattern with a felt-tip pen.

Where hardened concrete is to have fresh concrete

placed on it, it should be given a coat of shellac

dissolved in methylated spirits, followed by the release

agent described above.

The mix to be used for the concrete jacket is:

1 cement

1 dry sand

1 stone, size about 6,7 or 9,5 mm

enough mixing water to produce an easily work-

able

consistence.

Jacket-first method

Concrete jacket

Rubber liner in at

least two pieces

Support the pattern, with temporary base attached, on a

table so that the first part of the mould is generally as near

horizontal as possible.

Make a wall along the line of the mould joint. A combination

of plaster of Paris, modelling wax, synthetic modelling clay

and strips of wood may be used.

Make wall

Note registration points:

liner to liner, liner to

jacket, jacket to jacket

Pattern

Wall, supported on blocks

Figure 2. Section through a rubber-lined mould

Temporary base

The following information applies to both methods:

If possible, make the end of the jacket flat and parallel

to the temporary base on the pattern. This will allow the

mould to stand upright when the concrete is being cast.

Although the rubber liner can be peeled off the casting,

the liner-jacket interface must be shaped to allow

separation without binding or distortion of the liner

(see Figure 3).

The release agent, which is used to prevent a casting

from sticking to the surface it is cast on, can be a thin

coating of thin lubricating oil or petroleum jelly thinned

Workbench with blocks to support pattern

Place a layer of clay or synthetic modelling clay (plasticine)

on the pattern. The thickness of the rubber liner will be

the same as the thickness of this layer which should not

anywhere be less than 5 mm. Remember to make provision

for registration (to prevent relative movement) of liner and

jacket as shown opposite.

Apply clay wall

Make mould for jacket,

cast second half of jacket

Layer of clay or synthetic clay

Make a mould for the first half of the jacket, apply release

agent to clay layer and mould and cast the concrete. One

or more holes through the jacket will be needed. The rubber liner will later be cast by pouring the liquid compound

through a hole in the jacket. A hole will also be required at

every high point in the liner to allow air to escape as the

compound flows into position. The pouring hole should be

15 to 20 mm in diameter and air-escape holes about 5 mm

in diameter. These holes should preferably be formed in

the jacket concrete when it is cast. Use greased metal rods

or wooden dowels which are twisted and removed as the

concrete starts to stiffen. If you forget to form the holes at

this stage they can, of course, be drilled once the concrete

has hardened.

Make mould for jacket, cast first half of jacket

Half of concrete

jacket

Mould for jacket

When the concrete has hardened, at least 24 hours after

casting, remove the jacket mould. Now turn over the

combination of pattern, clay layer and jacket. Apply a clay

layer to the second half of the pattern, once again making

Remove jacket mould,

turn over and apply clay layer

Remove one half of the concrete jacket and carefully remove

the clay layer from the same side of the pattern. Apply

release agent to the pattern, the edge of the clay on the

opposite side, and the interior surface of the jacket. Place

the jacket in position.

Remove jacket mould,

remove clay layer from one half

Holes through jacket - drilled

or formed

(Holes through

bottom half of

jacket not shown)

Mix some pourable-grade rubber compound with catalyst as

recommended by the manufacturer. Pour slowly through the

pouring hole in the jacket. The compound will flow sluggishly

to fill the gap left by the removal of the clay. Tilt the assembly

slightly to each side for a while to encourage the compound

to flow into all areas. Continue to pour in compound until it

starts to rise in the pouring and air-escape holes in the jacket.

Cast first half or liner using

pourable grade rubber compound

Pouring hole

Rubber liner

Clay layer

Clay layer

provision for registration.

Make a mould for the next piece of jacket, apply release

agent and cast concrete with pouring and air-escape holes

as described above.

When the first half of the liner has cured, turn the assembly

over, lift off the uppermost jacket and remove the rest of

the clay. Apply release agent and cast the second half of

the liner in the same way as the first. When this has cured,

open the mould and remove the pattern. Cut off any liner

compound which has set in the pouring or air-escape holes

in the jacket.

Turn over, open jacket, remove rest of clay layer,

reassemble jacket and cast second half of liner

Remove raised edges of wall, make mould for

concrete, cast first half of jacket

Concrete

Liner-first method

Support the pattern, with temporary base attached, on a

table so that the first part of the mould is generally as near

horizontal as possible.

Make a wall along the line of the mould joint. A combination of plaster of Paris, modelling wax, synthetic modelling

clay, and strips of wood may be used. The wall should be

provided with registration cones and a raised edge.

Apply release agent to the pattern and to the wall.

the pattern and the edge of the liner, and apply the second

half of the liner as before.

Make a mould for the second half of the jacket, apply release

agent where necessary and cast the concrete.

Remove mould and wall, turn over,

apply second half of rubber liner

Rubber liner

Make wall (supported on blocks),

apply release agent

Pattern

Wall with raised edges

When the concrete has hardened, remove the mould from the

jacket, open the mould assembly and remove the pattern.

Temporary base

Make mould for concrete,

cast second half of concrete jacket

Workbench with blocks

to support pattern

Concrete

Mix some trowellable grade (also called thixotropic grade)

rubber compound with catalyst as recommended by the

manufacturer and apply to the pattern and wall with a

spatula. The piece of liner must be completed in a single

operation and minimum thickness should be 5 mm.

When the compound has cured, remove the raised edges

from the wall and make a mould for the uppermost half of

the jacket.

Apply trowellable (thixotropic)

grade rubber liner compound

Half of rubber liner

Apply release agent to the mould but none is required on the

rubber liner. Cast the first half of the jacket.

When the concrete has hardened sufficiently, remove the

jacket mould, turn the assembly over, apply release agent to

Mould for concrete

4. Preparing the mould for casting

concrete

Concrete will not stick to rubber. A release agent on

the mould liner is therefore not required. It is, however,

advisable to coat the meeting surfaces of the liner joint with

petroleum jelly before assembling the mould. This helps

to seal the joint and prevent loss of water from the fresh

concrete during casting.

When assembled, the mould can be kept closed with wire

wrapped around it and twisted to force the two halves

together. Small moulds may be held together with a number

of rubber bands cut from the inner tube of a car tyre.

5. Casting

7. Repairing blowholes

Mixing the concrete

Blowholes, which are small air holes that sometimes form in

the surface of the casting, can be filled with a mixture of:

Mix proportions are:

1 cement

1 concrete sand

1 stone

enough water to make the concrete sluggishly pourable

Cement:

2 parts of the cement used for the casting

1 part of white portland cement (to get a better

colour match)

or, for small castings use:

1 cement

2 coarse concrete sand

enough water to make the concrete sluggishly pourable

Mixing fluid:

2 parts water

1 part polymer emulsion (acrylic or styrene

butadiene)

The biggest particles in the concrete should not be more

than a quarter of the width of the narrowest part of the

casting.

Make the mixture to the consistence of toothpaste or slightly

stiffer. Fill each cavity carefully with a small spatula and

finish off flush with the surrounding concrete. Do not wet the

concrete before filling blowholes.

In hot weather, keep the cement, sand and stone in the

shade and use chilled water for mixing the concrete so that

the working time is not reduced by earlier setting of the

cement.

Mix the concrete thoroughly in plastic dish using a spade

(see Equipment in section 1).

Placing and compacting

Place the concrete in shallow layers in the mould. Compact

each layer thoroughly by using the end of a rod with a

vigorous up-and-down motion through the layer being

compacted to fluidise the concrete and allow air bubbles to

escape. (A wooden dowel rod is suitable for small castings

while a broomstick may be used for larger castings.) Be

particularly thorough near the surface of the mould and in

corners. Do not allow the compacting rod to rub against the

mould.

It is a good idea to use a light of some sort to inspect the

interior of a deep mould while casting the concrete.

Never try to place and compact the concrete in a hurry. At

normal temperatures the mixture should be workable for

about 1H hours.

Remember to cast in sockets or nuts if required for

anchorages for fixing the completed sculpture to the base.

Continue to place and compact the concrete until the mould

is full.

Scrape the concrete off flush with the edge of the mould.

Wait for two or three hours for the concrete to stiffen and

then trowel the concrete smooth while pressing it down

firmly to compact the surface.

Cover the exposed concrete with plastic sheeting.

6. Demoulding

The mould can be opened and the casting removed usually

between 24 and 48 hours after casting.

Take care to handle the mould in such a way that the casting

and mould are not damaged.

The mould should be cleaned as soon as it is removed from

the casting and stored where it will not be damaged.

8. Curing

Cover the casting with damp cloths and plastic sheeting and

leave covered for at least seven days.

9. Colouring the casting

This can be done in three different ways:

By including a pigment in the mixture

By staining the surface

By painting

Pigmenting

Pigments are integral colouring agents in powder form. Black

and shades of yellow, red and brown are based on iron

oxides. A green pigment is made from chrome oxide. The

colouring power of a pigment depends on purity and fineness

and only the best quality synthetic pigments should be used.

Cement, being a relatively fine powder, also has a

pigmenting effect. This is why unpigmented concrete made

with grey cement normally has a grey colour. The fine

particles in sands (which are often iron oxides) may also

have a pigmenting effect.

A pigment should therefore always be tested with the

specific combination of cement, sand and stone to be used

for the concrete.

If a bright colour is required, use white portland cement

(which is more expensive than grey) and white or light-coloured sands.

Pigments should always be passed through a fine sieve

(a kitchen sieve is suitable) before being added to the

concrete mixture. A few small dry stones in the sieve will

help to break up lumps.

Pigment dosage, which is normally about 5% of the amount

of cement, must be very accurately controlled for uniform

results and quantities should be weighed and not measured

by volume.

Staining the surface of hardened concrete

Four methods can be used. Note that absolutely uniform

colouring (like, for example, a coat of paint) should not be

expected - the colour will always be patchy to some extent

because concrete is not uniformly absorbent. In addition, the

colour of the base concrete will be visible through the stain. It

is worth experimenting to achieve the best results.

Appendix

Chemical staining

A 10% solution of ferrous sulphate in water is applied to the

surface of the concrete with a paintbrush. This causes a

chemical reaction in the cement paste at the surface.

A yellowish buff colour results after some time. The treatment

can be repeated for a deeper colour. Chemical staining is most

effective when it is done soon after the concrete has hardened

- ie when the concrete is weeks and not months old.

Chemical Traders of SA (Pty) Ltd

(Stock most materials mentioned in the leaflet)

Tel: 011 828 7800

Fax: 011 828 8881

Staining with pigments

Allow the concrete to dry thoroughly. Drying may take

some days.

Mix up some iron oxide or other concrete pigment with water.

Proportions are not critical but 20 millilitres in half a litre of

water should be satisfactory. The easiest way to mix is to

shake up the mixture in a closed wide-mouth bottle with a

handful of small stones.

Apply the mixture generously as a wash to the concrete until

the whole surface has been wetted. Leave to dry. Excess

pigment can later be washed off with water if necessary.

The colouring effect is caused by minute particles of pigment lodging in pores in the surface of the concrete and is

surprisingly long-lasting.

Staining with acrylic paint

Make a mixture of acrylic paint - either artists colours or pure

acrylic wall paint - and water. One volume of acrylic to ten

volumes of water is normally suitable. Apply this as a wash

to dry concrete, allow to soak in and remove any excess.

Repeat if necessary once the stain has dried. Successive

washes may be of different colours. The advantage of using

acrylic paints is that a wide range of colours is available.

Using a proprietary stain

These are obtainable, in a limited range of colours,

from builders merchants. Apply in accordance with the

manufacturers instructions. A single coat usually produces a

satisfactory finish, while a second coat can result in a rather

varnished appearance.

Painting

Pure acrylic paints are the most suitable. Uniform colours

can be obtained by painting and they will cover the base concrete completely with an opaque coating. Interesting mottled

effects are also possible if some of the paint is removed

while it is still wet by rubbing with a damp cloth.

Suppliers of materials

For small quantities contact:

For larger quantities of specific materials contact:

Light coloured sand

B&E Silica

Tel: 013 665 7900

Fax: 013 665 7910

Delmas Silica

Tel: 013 665 7200

Fax: 013 665 7280

Pigments

Cathay Pigments

Tel: 011 964 2306

Fax: 011 964 1127

Cemcrete

Tel: 011 474 2415

Fax: 011 474 2416

Lanxess SA (Pty) Ltd

Tel: 011 921 5196

Fax: 011 921 5128

Rolfes Colour Pigments

International

Tel: 011 874 0686

Fax: 011 874 0789

ZZ Chemicals

Tel: 011 482 1854

Fax: 011 482 3250

Silicone for making moulds

Designer Ideas CC

Tel: 011 433 1713

Fax: 011 433 2705

Cel: 083 676 9898

Silicone Mouldmakers Guild

Tel: 011 433 1713

Fax: 011 433 2705

Cel: 083 676 9898

Silicone and Technical Products

Tel: 011 452 5164

Fax: 011 609 4164

Tel: 021 534 9055

Fax: 021 534 6611

White Cement

Cathay Pigments

Tel: 011 964 2306

Fax: 011 964 1127

Pudlo

Tel: 021 448 0607

Fax: 021 448 4622

Cemcrete

Tel: 011 474 2415

Fax: 011 474 2416

Union Flooring Tiles

Tel: 011 455 4220

Fax: 011 455 5395

Limeco Trust

Tel: 031 469 1849

Fax: 031 469 1684

Cement & Concrete Institute

PO Box 168, Halfway House, 1685

Tel (011) 315-0300 Fax (011) 315-0584

e-mail info@cnci.org.za website http://www.cnci.org.za

Published by the Cement & Concrete Institute, Midrand, 1999, reprinted 2002, 2006.

Cement & Concrete Institute

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- Russell PHD 2015 Progressive Collapse of Reinforced Concrete Flat Slab StructuresDokumen238 halamanRussell PHD 2015 Progressive Collapse of Reinforced Concrete Flat Slab StructuresRm1262Belum ada peringkat

- Technoslide Elastomeric-Plain-Sliding-Bearings-For-Bridges-Structures-BrochureDokumen13 halamanTechnoslide Elastomeric-Plain-Sliding-Bearings-For-Bridges-Structures-BrochureRm1262Belum ada peringkat

- Extend Abstract - 67792 - Joao GeadaDokumen10 halamanExtend Abstract - 67792 - Joao GeadaRm1262Belum ada peringkat

- Henderson, Johnson & Wood 2002 Enhancing The Whole Life Structural Performance of Multi-Storey Car ParksDokumen50 halamanHenderson, Johnson & Wood 2002 Enhancing The Whole Life Structural Performance of Multi-Storey Car ParksRm1262Belum ada peringkat

- The Concrete Society - Fire DamageDokumen6 halamanThe Concrete Society - Fire DamageRm1262Belum ada peringkat

- Annerel & Taerwe 2008 Diagnosis of The State of Concrete Structures After FireDokumen6 halamanAnnerel & Taerwe 2008 Diagnosis of The State of Concrete Structures After FireRm1262Belum ada peringkat

- IMIESA April 2021Dokumen60 halamanIMIESA April 2021Rm1262Belum ada peringkat

- BinsDokumen17 halamanBinsRm1262Belum ada peringkat

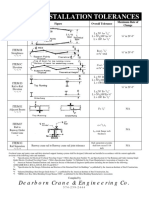

- Crane Runway Installation Tolerances-BechtelDokumen1 halamanCrane Runway Installation Tolerances-BechtelRm1262Belum ada peringkat

- UJ - EngineeringManagement 2020Dokumen4 halamanUJ - EngineeringManagement 2020Rm12620% (1)

- Sarens SarspinV.11.10.10Dokumen4 halamanSarens SarspinV.11.10.10Rm1262Belum ada peringkat

- Narayangharh-Mugling HighwayDokumen85 halamanNarayangharh-Mugling HighwayRm1262Belum ada peringkat

- Bituthene 3000-3000 HCDokumen2 halamanBituthene 3000-3000 HCRm1262Belum ada peringkat

- SikaBond Rapid DPM PDSDokumen4 halamanSikaBond Rapid DPM PDSRm1262Belum ada peringkat

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5795)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (588)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (74)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (895)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (400)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (345)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2259)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (266)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)

- Sustainable Medium Strength Geopolymer With Fly Ash and GGBS As Source MaterialsDokumen11 halamanSustainable Medium Strength Geopolymer With Fly Ash and GGBS As Source Materialsjyothi ramaswamyBelum ada peringkat

- m20 Concrete Mix Design ReportDokumen3 halamanm20 Concrete Mix Design ReportFUTURE STRUCTURAL CONSULTANTS50% (2)

- 08 HardwareDokumen32 halaman08 HardwareRuri ChanBelum ada peringkat

- Advances in Continuous Casting PDFDokumen4 halamanAdvances in Continuous Casting PDFPrakash SarangiBelum ada peringkat

- Hot-Dip Galvanizing - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaDokumen3 halamanHot-Dip Galvanizing - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediadiehardjamesbondBelum ada peringkat

- Arubis Catalogue2015 ENG PDFDokumen15 halamanArubis Catalogue2015 ENG PDFCiprian CretuBelum ada peringkat

- Perbandingan Standar GalvanizeDokumen1 halamanPerbandingan Standar GalvanizeHana ZahraBelum ada peringkat

- B02-S01 Rev 4 Jun 2018 Fabrication of Structural and Miscellaneous SteelDokumen17 halamanB02-S01 Rev 4 Jun 2018 Fabrication of Structural and Miscellaneous Steel15150515715Belum ada peringkat

- Chapter 1 PPT 3Dokumen44 halamanChapter 1 PPT 3Shumaila QadirBelum ada peringkat

- Mathcad-Isolated Foundation BBSDokumen20 halamanMathcad-Isolated Foundation BBSValentinBelum ada peringkat

- AB - Insulbar Shear Free Profile Brochure Eng PDFDokumen4 halamanAB - Insulbar Shear Free Profile Brochure Eng PDFmistakyBelum ada peringkat

- NMS Complete EnglishDokumen17 halamanNMS Complete EnglishthamindulorensuBelum ada peringkat

- Sikadur 31 CF Normal Pds enDokumen4 halamanSikadur 31 CF Normal Pds enyacovaBelum ada peringkat

- Astm 1011Dokumen9 halamanAstm 1011calidad campana100% (1)

- Oib Technical Spec 21,22,23Dokumen586 halamanOib Technical Spec 21,22,23kali highBelum ada peringkat

- Technical Supplement 14R Design and Use of Sheet Pile Walls in Stream Restoration and Stabilization ProjectsDokumen36 halamanTechnical Supplement 14R Design and Use of Sheet Pile Walls in Stream Restoration and Stabilization ProjectsThaung Myint OoBelum ada peringkat

- Vdocuments - MX Chapter 7 Design of Concrete StructureDokumen31 halamanVdocuments - MX Chapter 7 Design of Concrete Structureaihr78Belum ada peringkat

- Design Hybrid Concrete Buildings PDFDokumen116 halamanDesign Hybrid Concrete Buildings PDFAdam Fredriksson100% (1)

- Steel Prices Middle EastDokumen1 halamanSteel Prices Middle EastSaher RautBelum ada peringkat

- Water Distribution SystemsDokumen49 halamanWater Distribution SystemsAnonymous fE2l3Dzl100% (1)

- Concrete TechnologyDokumen118 halamanConcrete Technologyeskinderm100% (30)

- OTTVDokumen61 halamanOTTVmaxwalkerdreamBelum ada peringkat

- Schedule of Rates 2017-18-1Dokumen210 halamanSchedule of Rates 2017-18-1tejus ConsultantsBelum ada peringkat

- Utilization of Waste Plastic in Manufacturing of Paver BlocksDokumen4 halamanUtilization of Waste Plastic in Manufacturing of Paver BlocksAragorn RingsBelum ada peringkat

- CemFIL AntiCrak HP 6736 Product Sheet WW 10-2014 Rev8 en FinalDokumen2 halamanCemFIL AntiCrak HP 6736 Product Sheet WW 10-2014 Rev8 en FinalvliegenkristofBelum ada peringkat

- Deret TribolistrikDokumen3 halamanDeret Tribolistrikrclara_1Belum ada peringkat

- Adwea Standard Quality Control Plan (SQCP) : For Ductile Iron FittingsDokumen17 halamanAdwea Standard Quality Control Plan (SQCP) : For Ductile Iron FittingsAmro HarasisBelum ada peringkat

- Flexal 80Dokumen1 halamanFlexal 80joseBelum ada peringkat

- Alite Modification by SO3 in Cement Clinker - An Industrial TrialDokumen7 halamanAlite Modification by SO3 in Cement Clinker - An Industrial TrialRaúl Marcelo Veloz100% (2)

- Cables and Wires CatalogueDokumen16 halamanCables and Wires CatalogueVENITHA KBelum ada peringkat