Dizzines Vertigo

Diunggah oleh

Muhammad Agung SwasonoHak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Dizzines Vertigo

Diunggah oleh

Muhammad Agung SwasonoHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Performance of DHI Score as a Predictor of Benign

Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo in Geriatric Patients with

Dizziness/Vertigo: A Cross-Sectional Study

Amrish Saxena*, Manish Chandra Prabhakar

Department of Medicine, Mahatma Gandhi Institute of Medical Sciences, Wardha, Maharashtra, India

Abstract

Background: Dizziness/vertigo is one of the most common complaint and handicapping condition among patients aged 65

years and older (Geriatric patients). This study was conducted to assess the impact of dizziness/vertigo on the quality of life

in the geriatric patients attending a geriatric outpatient clinic.

Settings and Design: A cross-sectional study was performed in a geriatric outpatient clinic of a rural teaching tertiary care

hospital in central India.

Materials and Methods: In all consecutive geriatric patients with dizziness/vertigo attending geriatric outpatient clinic, DHI

questionnaire was applied to assess the impact of dizziness/vertigo and dizziness associated handicap in the three areas of a

patients life: physical, functional and emotional domain. Later, each patient was evaluated and underwent Dix-Hallpike

maneuver by the physician who was blind of the DHI scoring of the patient.

Statistical Analysis Used: We compared means and proportions of variables across two categories of benign paroxysmal

positional vertigo (BPPV) and non-BPPV. For these comparisons we used Students t-test to test for continuous variables, chisquare test for categorical variables and Fishers exact test in the case of small cell sizes (expected value,5).

Results: The magnitude of dizziness/vertigo was 3%. Of the 88 dizziness/vertigo patients, 19 (22%) and 69(78%) cases,

respectively, were attributed to BPPV and non-BPPV group. The association of DHI score $50 with the BPPV was found to

be statistically significant with x2 value = 58.2 at P,0.01.

Conclusion: DHI Score is a useful tool for the prediction of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Correct diagnosis of BPPV

is 16 times greater if the DHI Score is greater than or equal to 50. The physical, functional and emotional investigation of

dizziness, through the DHI, has demonstrated to be a valuable and useful instrument in the clinical routine.

Citation: Saxena A, Prabhakar MC (2013) Performance of DHI Score as a Predictor of Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo in Geriatric Patients with Dizziness/

Vertigo: A Cross-Sectional Study. PLoS ONE 8(3): e58106. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0058106

Editor: Alejandro Lucia, Universidad Europea de Madrid, Spain

Received June 11, 2012; Accepted February 1, 2013; Published March 5, 2013

Copyright: 2013 Saxena, Prabhakar. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits

unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Funding: This study was partly funded by the Indian Council of Medical Research, New Delhi, India. Manish Chandra Prabhakar, a medical student, was awarded

the short term studentship (2010) to conduct this study (URL: http://www.icmr.nic.in/shortr.htm). The Indian Council of Medical Research had no role in study

design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. No additional external funding received for this study.

Competing Interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

* E-mail: dramrishsaxena@rediffmail.com

Dizziness/vertigo can be produced by peripheral vestibular

disorders or central nervous system disorders or by combined

lesions, and other conditions. Peripheral vestibular disorders

include BPPV (benign paroxysmal positional vertigo), acute

labyrinthitis, acute vestibular neuritis, Menieres disease, recurrent

vestibulopathy, middle ear disease, otosclerosis and perilymphatic

fistula. Among these, BPPV was the most frequent peripheral

vestibular diagnosis reported in previous studies [4,7,8]. Posterior

canal BPPV is more common than lateral canal and anterior canal

BPPV, constituting approximately 85 to 95 percent of BPPV cases

[9,10]. The recurrence rate of BPPV is 27%, and relapse mainly

occurs in the first few months [11]. Central nervous system

disorders include cerebrovascular diseases such as transient

ischaemic attacks (TIAs), brain stem disease, cerebellar disease,

demyelinating diseases like multiple sclerosis, cerebellopontine

Introduction

Dizziness or vertigo is an ill defined subjective sensation of

postural instability or of illusory motion of self or environment

either as a sensation of spinning or falling. Dizziness is one of the

most common complaint among all outpatients and the single

most common complaint, handicapping condition among patients

aged 65 years and older. The prevalence of dizziness ranges from

4% to 30% in this age group [1,2]. The lifetime prevalence of

dizziness was 29.3%; the 1-year prevalence was found to be 18.2%

in a community elderly population [3]. The annual prevalence of

dizziness/vertigo in the adult population of 22.9% was reported in

Germany [4]. Dizziness is associated with functional disability, and

1020% of sufferers fall because of their symptoms [5,6].

PLOS ONE | www.plosone.org

March 2013 | Volume 8 | Issue 3 | e58106

DHI Score as a Predictor of BPPV

angle tumor, posterior fossa lesions, infections and migraine.

Other conditions which may cause dizziness are cervical

spondylosis, postural hypotension, endocrinal diseases, drugs,

vasculitis, anemia, polycythemia, psychological factors and

cardiovascular diseases [2,12].

The physical, emotional and functional disturbances that are

associated with several kinds of dizzinesses harm the professional,

social and domestic activities of the patient. It may cause

difficulties on the patients daily life and even reduce their life

quality. There is a paucity of literature about the personal and

health care burden of dizziness and vertigo in the geriatric

population. Little is known from the previous studies about the

handicapping effect of dizziness imposed by vestibular causes in

comparison to non-vestibular causes in the geriatric age group.

Our study was conducted to assess the magnitude and impact of

dizziness/vertigo on the quality of life in the geriatric patients

attending a geriatric outpatient clinic in a rural medical college

hospital. We also aimed to determine whether performance of

Dizziness Handicap inventory (DHI) score would predict the

diagnosis of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV).

with nausea and either imbalance or oscillopsia. The patients with

vertigo/giddiness in which a characteristic torsional (rotational)

nystagmus occurred after a brief latent period (15 seconds),

lasting less than one minute, elicited during the Dix-Hallpike

maneuver were considered to have a positive Dix-Hallpike test,

while those without these features were considered to have a

negative result [13]. Visualization of the nystagmus was aided by

the use of optical Frenzel glasses, which eliminate visual fixation.

The Dix-Hallpike maneuver is considered the gold standard test

for the diagnosis of BPPV [14,15]. Rotational vertigo was defined

as an illusion of self-motion or object motion, and positional

vertigo was defined as vertigo or dizziness precipitated by changes

in head position such as lying down or turning in bed [4,7,16].

Patients with dizziness/vertigo who did not fulfill criteria for BPPV

were classified in non-BPPV group.

Demographic data, including age and sex; personal habits like

smoking; past history of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, ischemic

heart disease or stroke; history of associated complaints like

tinnitus, impaired hearing, pain in ear and ear discharge were

obtained during baseline interview. Current smokers are classified

as persons who reported smoking at least 100 cigarettes in their life

and who currently smoke every day or on some days [17].

Presence of tinnitus was assessed by a positive response to the

question: Have you experienced any prolonged ringing, buzzing

or other sound in your ears or head within the past one

monththat is, lasting for 5 min or longer? Patients were

classified as hypertensive if the mean of 2 blood pressure

recordings was 140 mm Hg or greater for systolic and 90 mm Hg

or greater for diastolic or if they reported having hypertension or

the use of antihypertensive medications [18]. Patients with a

systolic blood pressure between 120 to 139 mm Hg or a diastolic

pressure between 80 to 89 mm Hg were classified as prehypertensive [18]. The patients were classified as diabetic if they

reported having diabetes mellitus with medications even if their

blood sugar were within the normal range. Some patients with

fasting plasma glucose .126 mg/dl or 2-hour postprandial plasma

glucose .200 mg/dl and with no past relevant history of diabetes

mellitus were also classified as newly detected diabetics [19].

Patients with past documented history of myocardial infarction or

angina were classified as having ischemic heart disease.

Patients with a self reported history or documentation of a

cerebrovascular accident(s) (stroke) were also recorded.

Blood pressure and heart rate were measured after the

participants had rested supine for at least 5 minutes. A standard

sphygmomanometer with an appropriate-sized cuff was used.

After blood pressure and heart rate were measured, the participant

was helped into a standing position. His or her arm was placed on

a portable stand that was level with the heart, and blood pressure

and heart rate measurements were repeated immediately after

standing and after 2 minutes. Postural or orthostatic hypotension

was diagnosed when there was a drop in systolic blood pressure of

20 mm Hg or more or of 10 mm Hg in diastolic blood pressure

Materials and Methods

Ethics

The study was approved by the ethics committee of Mahatma

Gandhi Institute of Medical Sciences (IRB00003623). We

obtained a written informed consent from all study participants

before enrolling them in the study.

Setting

The study was conducted in the department of Medicine,

Mahatma Gandhi Institute of Medical Sciences, Sevagram which

is a 650-bedded teaching tertiary care hospital located in a town in

central India. The department of Medicine has a daily adult

outpatients (1364 yrs) of approximately 200 and a geriatric

outpatients (65 yrs or above) of about 30. Most patients visiting the

hospital come from rural areas. All patients aged 65 years or above

(geriatric patients) are screened and examined first in the geriatric

outpatient clinic where after a brief history and examination,

appropriate referrals to specialists are advised.

Study Design

Between April 1, 2010 and July 31, 2010, a cross-sectional study

was conducted to identify and assess geriatric patients with

dizziness/vertigo attending geriatric outpatient clinic. All consecutive geriatric patients complaining of more than five episodes of

dizziness/vertigo were included in the study. Patients were

excluded if they had history of dementia, Parkinsons disease,

Alzheimers disease, severe depression, advanced malignancy or

not provide written informed consent.

A diagnosis of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV)

required combination of a positive Dix-Hallpike test and a history

of rotational vertigo, or positional vertigo, or recurrent dizziness

Table 1. Sex distribution of geriatric patients among peripheral-vestibular vertigo and non-vestibular group.

sex

Peripheral-vestibular vertigo

(n = 19)

Non-vestibular vertigo (n = 69)

Total (n = 88)

Male

7 (37%)

41 (59%)

48 (55%)

Female

12 (63%)

28 (41%)

40 (45%)

X2 = 3.06, P value .0.05. Values are number of patients. Figures in parenthesis represent the column percentage.

doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0058106.t001

PLOS ONE | www.plosone.org

March 2013 | Volume 8 | Issue 3 | e58106

DHI Score as a Predictor of BPPV

Table 2. Distribution of comorbid diseases/cardiovascular risk factors among peripheral-vestibular vertigo and non-vestibular

vertigo group.

Comorbid diseases/cardiovascular

risk factors

Peripheral-vestibular

vertigo (n = 19)

Non-vestibular vertigo

(n = 69)

Total (n = 88)

P value

Hypertension*

5 (18%)

23 (82%)

28 (32%)

.0.05

Pre-hypertension*

8 (24%)

25 (76%)

33 (38%)

.0.05

Diabetes mellitus*

3 (25%)

9 (75%)

12 (14%)

.0.05

Ischemic heart disease*

2 (20%)

8 (80%)

10 (11%)

.0.05

Cerebrovascular stroke*

0 (0%)

5 (100%)

5 (6%)

.0.05

Current smokers*

3 (21%)

11 (79%)

14 (16%)

.0.05

*Expected cell count in one of the cells was less than 5 so Fishers exact test was used. Values are number of patients. Figures in parenthesis represent the row

percentage.

doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0058106.t002

two minutes after standing from the supine position with

associated symptoms [20].

The Dizziness Handicap Inventory (DHI) Questionnaire, which

has been developed by Jacobson and Newman (1990) was used to

assess the impact of dizziness on patients daily life [21]. It

evaluates the dizziness associated to the incapacities and handicap

in the three areas of a patients life: Physical, functional and

emotional (see Text S1). In the geriatric outpatient clinic, patients

were asked to complete the Dizziness Handicap Inventory (DHI)

consisting of 25 questions, and a total score (0100 points) is

obtained by summing ordinal scale responses, higher scores

indicating more severe handicap. The 25 items were grouped into

three dimensions: functional, emotional, and physical aspects of

dizziness and unsteadiness. There were nine questions within each

of the functional and emotional dimensions; with a maximum

score of 4 for each item. Within the physical dimension there were

seven questions with a maximum score of 4 for each. First, DHI

questionnaire of the patient was filled by a social worker in the

geriatric outpatient clinic and later the patient was evaluated and

underwent Dix-Hallpike maneuver by the physician who was

blind of the DHI scoring of the patient. After history and

examination patients were referred to ENT outpatient clinic for

specialist opinion and pure tone audiometry. Pure-tone audiometry was performed by audiologist in sound-treated booths, using

standard ELKON 3N3 Multi clinical audiometer (India made).

Hearing impairment was determined as the pure-tone average of

audiometric hearing thresholds at 500, 1000 and 2000 Hz

(PTA0.52 KHz), defining any hearing loss as PTA0.52 KHz

.25 dB with the criterion based on the classification of the WHO

[22].

Statistical Analysis

We used SPSS software (version 16.0) to analyze the characteristics of the study population. We compared means and

proportions of variables across two categories of BPPV and nonBPPV. For these comparisons we used the Students t-test for

continuous variables, the chi-square test for categorical variables

and the Fishers exact test in the case of small cell sizes (expected

value,5). All comparisons were two-tailed. We considered the

difference to be statistically significant if the P value was less than

0.05. To determine the best cut-off value of the DHI score for the

diagnosis of BPPV, we used the receiver operating characteristic

(ROC) curve analysis.

Results

The overall magnitude of dizziness/vertigo was 3% (88 of 2900

geriatric patients screened in the geriatric OPD had dizziness/

vertigo). Of the 88 dizziness/vertigo patients, 19 (22%) and

69(78%) cases, respectively, were assigned to the BPPV and nonBPPV group.

The mean age of patients in the BPPV group and non-BPPV

group were 70 years (SD = 4.95) and 69 years (SD = 4.21)

respectively. There was no significant difference between the

mean age of patients in two categories (p.0.05).

Of the total 88 patients with dizziness/vertigo, 48 (55%) were

males and 40 (45%) were females. There were 12 (63%) females in

the BPPV group (n = 19) and 28 (41%) females were in the nonBPPV group (n = 69). There were 7 (37%) males in the BPPV

group (n = 19) and 41 (59%) males in the non-BPPV group

(n = 69). Although there were more females (63%) in the BPPV

group and more males (59%) in the non-BPPV group, the

difference was not significant (P.0.05) (Table 1).

Table 3. Distribution of ENT Symptoms among peripheral-vestibular vertigo and non-vestibular vertigo group.

ENT symptoms

Peripheral-vestibular vertigo Non-vestibular vertigo

(n = 19)

(n = 69)

Total (n = 88)

P value

Tinnitus*

12 (75%)

16 (18%)

,0.01

4 (25%)

Impaired hearing*

3 (20%)

12 (80%)

15 (17%)

.0.05

Ear pain*

2 (25%)

6 (75%)

8 (9%)

.0.05

Ear discharge*

0 (0%)

4 (100%)

4 (4%)

.0.05

*Expected cell count in one of the cells was less than 5 so Fishers exact test was used. Values are number of patients. Figures in parenthesis represent the row

percentage.

doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0058106.t003

PLOS ONE | www.plosone.org

March 2013 | Volume 8 | Issue 3 | e58106

DHI Score as a Predictor of BPPV

Table 4. Diagnostic and predictive accuracy of DHI score

using Dix-Hallpike test as a gold standard.

Diagnostic/predictive accuracy

value

Sensitivity (%)

94.7

Specificity (%)

94.2

Positive predictive value (%)

81.0

Negative predictive value (%)

98.0

Positive likelihood ratio

16.33

doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0058106.t004

Discussion

In our study, we were able to establish that a DHI score greater

than or equal to 50 in a geriatric patient with dizziness/vertigo is a

good predictor of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Patients in

the BPPV group (mean DHI, 65.68611.41) demonstrated greater

handicap than those in the non-BPPV group (mean DHI,

27.65612.07). The magnitude of dizziness/vertigo in our geriatric

patients attending geriatric outpatient clinic was found to be 3%,

which inflict a considerable health care burden.

Although there were more females (63%) in the BPPV group

and more males (59%) in the non-BPPV group in our study, but

the association of a particular gender with either group (BPPV vs.

non-BPPV) was not found to be statistically significant. In previous

studies, an association of vestibular vertigo with female sex was

found in general population [7,8]. The authors suggested that

premenstrual or oral contraceptive-related hormonal changes may

increase the risk of vestibular disorders.

The association of each comorbid illness i.e. hypertension,

diabetes mellitus, ischemic heart disease or cerebrovascular stroke

(cardiovascular diseases) with either group (BPPV vs. non-BPPV)

was not found to be statistically significant. However in the past

studies, hypertension and stroke had an independent effect on

BPPV whereas diabetes and coronary heart disease was not

associated with BPPV [7,8]. The authors suggested that hypertension can lead to vascular damage to the inner ear and thus to

BPPV. Vertebrobasilar ischemia was suggested as a predisposing

factor for BPPV. It can be a sequel to labyrinthine ischemia that

probably facilitates detachment of otoconia from the otolith

membrane. Similarly, another study found an association between

rotatory vertigo and stroke [23]. In a previous study done by

Cohen et. al., diabetes was found to be unusually prevalent in

BPPV patients [24]. In our study, if our sample size has been large

with more number of patients with HT/DM/IHD/CV stroke in

each subgroup, probably we could get a significant association of

these cardiovascular risk factors with either group (BPPV vs. nonBPPV).

After classifying the patients in either group (BPPV vs. non-

Figure 1. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve for DHI

scoring.

doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0058106.g001

Of the 88 patients, 28 (32%) patients had hypertension, 12

(14%) patients had diabetes mellitus, 10 (11%) patients had

ischemic heart disease, 5 (6%) patients had cerebrovascular stroke.

The association of each comorbid illness i.e. hypertension, diabetes

mellitus, ischemic heart disease and cerebrovascular stroke

(cardiovascular diseases) with either group (BPPV vs. non-BPPV)

was not found to be statistically significant (P.0.05). After

classifying the patients in either group (BPPV vs. non-BPPV) as

those with cardiovascular diseases (HT+DM+IHD+CV stroke)

and those without cardiovascular diseases, we found no statistically

significant association of cardiovascular diseases with BPPV/nonBPPV (P.0.05). Of the 88 vertigo patients, 14 (16%) patients were

current smokers. There were 3 (21%) current smokers in the BPPV

group and 11 (79%) current smokers in the non-BPPV group. The

association of current smoking with either group (BPPV vs. nonBPPV) was not statistically significant (P.0.05)(Table 2). None of

the patients in the BPPV group had postural hypotension, whereas

8 (9%) patients in the non-BPPV group had postural hypotension.

ENT symptoms: Of the total 88 patients, 16 (18%) had tinnitus,

15 (17%) had impaired hearing, 8 (9%) had ear pain and 4 (4%)

had ear discharge. The association of tinnitus with the BPPV

group was found to be statistically significant (P,0.01) but

impaired hearing, pain in ear and ear discharge were not

significantly associated with either group i.e. BPPV vs. non-BPPV

(P.0.05) (Table 3).

The mean DHI score of patients in the BPPV group was

65.68611.41, whereas in the non-BPPV group it was

27.65612.07. From the receiver operating characteristic (ROC)

curve analysis (Figure 1), best cut-off of DHI score for diagnosis of

BPPV was found to be 50 with area under the ROC curve (AUC)

being 0.982, sensitivity of 94.7%, specificity of 94.2%, and positive

likelihood ratio of 16.33 (Table 4). The association of DHI score

$50 with the benign paroxysmal positional vertigo was found to

be statistically significant with x2 value = 58.2 at P,0.01 (Table 5).

Table 5. DHI score and Dix-Hallpike test.

Dix-Hallpike test as a gold standard

DHI score

Peripheral-vestibular

vertigo

Non-vestibular vertigo

Score./ = 50

18

Score,50

65

(X2 = 58.2 at P,0.01).

doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0058106.t005

PLOS ONE | www.plosone.org

March 2013 | Volume 8 | Issue 3 | e58106

DHI Score as a Predictor of BPPV

BPPV)

as

patients

with

cardiovascular

diseases

(HT+DM+IHD+CV stroke) and without cardiovascular diseases,

we found no statistically significant association of these groups with

BPPV/non-BPPV. If our study was done with a larger sample size

having more number of patients in the cardiovascular group then

a possible significant association between cardiovascular disease

group and BPPV/non-BPPV group could be found. In the

previous studies, an association was found between cardiovascular

risk factors and dizziness [3,5,25]. The authors postulated that

vascular disease seems important in the pathogenesis of dizziness

in old age.

The association of current smoking with either group (BPPV vs.

non-BPPV) was not statistically significant which is in line with

previous studies [5,7,8]. In our study, 8 (9%) patients in the nonBPPV group had postural hypotension. Similarly, postural

hypotension were noted in 14% of subjects in a previous study

done by Ensrud et al. [20].

In our study, the association of tinnitus with the BPPV group

was found to be statistically significant (P,0.01), reflecting the

frequent otogenic origin of BPPV but impaired hearing, pain in

ear and ear discharge were not significantly associated with either

group i.e. BPPV vs. non-BPPV which is in line with the previous

studies [5,7,26].

Our study has several strengths. Our patients represent typical

rural Indian patients form central India. By including every

consecutive outpatient we avoided the selection bias. We made a

blind assessment (filling DHI questionnaire and physician evaluation) of the patient. We used a validated tool which can be used

easily in outpatient clinic or bedside.

The limitation of our study is that the results of the study cannot

be generalized to the community settings. Furthermore, no study

patient underwent posturography, electronystagmography, tilttable testing, caloric testing or neuroimaging (MRI) [27,28,29].

Although these tests may have helped to identify the presence of

specific causes in a subset of our patients, but that was not the

purpose of our study. Our risk factor analysis is limited by the

cross-sectional design of the study. In patients with vertigo/

dizziness having a positive Dix-Hallpike test, there might be few

patients who had more than one factor involved (superimposed on

a possible BPPV) in addition to the effects of aging itself.

Conclusion

We conclude from the present study that DHI score is a useful

tool for the prediction of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo

(BPPV). Correct diagnosis of BPPV is 16 times greater if the DHI

score is greater than or equal to 50. The physical, functional and

emotional investigation of dizziness, through the DHI, has

demonstrated to be a valuable and useful instrument in the

clinical routine.

Suggestion

Among patients presenting with dizziness/vertigo in geriatric

outpatient clinic, the performance of DHI score in complement to

careful clinical history could be one of the useful and valuable

parameters for identifying patients with BPPV. Such patients can

be subjected to therapeutic maneuvers (vestibular rehabilitation

therapy), having more acceptances to this treatment, after realizing

their own difficulties during the questionnaire application. It can

avoid unnecessary and costly investigations especially in the

resource-limited settings. It is simple and must be included in

routine evaluation of geriatric patients with dizziness/vertigo at

daily dizziness clinic.

Supporting Information

Text S1 DHI Questionnaire.

(PDF)

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank our patients and Mr. Surendra Belurkar, a social worker

for their cooperation in this study.

Author Contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: AS. Performed the experiments:

AS MCP. Analyzed the data: AS MCP. Contributed reagents/materials/

analysis tools: AS MCP. Wrote the paper: AS.

References

1. Colledge NR, Barr-Hamilton RM, Lewis SJ, Sellar RJ, Wilson JA (1996)

Evaluation of investigations to diagnose the cause of dizziness in elderly people: a

community based controlled study. BMJ 313: 788792.

2. Sloane PD, Coeytaux RR, Beck RS, Dallara J (2001) Dizziness: state of the

science. Ann Intern Med 134: 823832.

3. Sloane P, Blazer D, George LK (1989) Dizziness in a community elderly

population. J Am Geriatr Soc 37: 101108.

4. Neuhauser HK, Radtke A, von Brevern M, Lezius F, Feldmann M, et al. (2008)

Burden of dizziness and vertigo in the community. Arch Intern Med 168: 2118

2124.

5. Colledge NR, Wilson JA, Macintyre CC, MacLennan WJ (1994) The prevalence

and characteristics of dizziness in an elderly community. Age Ageing 23: 117

120.

6. Oghalai JS, Manolidis S, Barth JL, Stewart MG, Jenkins HA (2000)

Unrecognized benign paroxysmal positional vertigo in elderly patients.

Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 122: 630634.

7. Neuhauser HK (2007) Epidemiology of vertigo. Curr Opin Neurol 20: 4046.

8. von Brevern M, Radtke A, Lezius F, Feldmann M, Ziese T, et al. (2007)

Epidemiology of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: a population based study.

J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 78: 710715.

9. Parnes LS, Agrawal SK, Atlas J (2003) Diagnosis and management of benign

paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV). CMAJ 169: 681693.

10. Korres S, Balatsouras DG, Kaberos A, Economou C, Kandiloros D, et al. (2002)

Occurrence of semicircular canal involvement in benign paroxysmal positional

vertigo. Otol Neurotol 23: 926932.

11. Perez P, Franco V, Cuesta P, Aldama P, Alvarez MJ, et al. (2012) Recurrence of

benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Otol Neurotol 33: 437443.

12. Kroenke K, Lucas CA, Rosenberg ML, Scherokman B, Herbers JE Jr, et al.

(1992) Causes of persistent dizziness. A prospective study of 100 patients in

ambulatory care. Ann Intern Med 117: 898904.

PLOS ONE | www.plosone.org

13. Dix MR, Hallpike CS (1952) The pathology symptomatology and diagnosis of

certain common disorders of the vestibular system. Proc R Soc Med 45: 341

354.

14. Furman JM, Cass SP (1999) Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. N Engl J Med

341: 15901596.

15. Fife TD, Iverson DJ, Lempert T, Furman JM, Baloh RW, et al. (2008) Practice

parameter: therapies for benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (an evidencebased review): report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American

Academy of Neurology. Neurology 70: 20672074.

16. Hanley K, T OD (2002) Symptoms of vertigo in general practice: a prospective

study of diagnosis. Br J Gen Pract 52: 809812.

17. Ryan H, Trosclair A, Gfroerer J (2012) Adult current smoking: differences in

definitions and prevalence estimates-NHIS and NSDUH, 2008. J Environ

Public Health: 111.

18. Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, Green LA, et al. (2003)

The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection,

Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure: the JNC 7 report. JAMA

289: 25602572.

19. American Diabetes Association (2010) Diagnosis and classification of diabetes

mellitus. Diabetes Care 33 Suppl 1: S6269.

20. Ensrud KE, Nevitt MC, Yunis C, Hulley SB, Grimm RH, et al. (1992) Postural

hypotension and postural dizziness in elderly women. The study of osteoporotic

fractures. The Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group. Arch Intern

Med 152: 10581064.

21. Jacobson GP, Newman CW (1990) The development of the Dizziness Handicap

Inventory. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 116: 424427.

22. Herrgard E, Karjalainen S, Martikainen A, Heinonen K (1995) Hearing loss at

the age of 5 years of children born preterma matter of definition. Acta Paediatr

84: 11601164.

March 2013 | Volume 8 | Issue 3 | e58106

DHI Score as a Predictor of BPPV

26. Moreno NS, Andre AP (2009) Audiologic features of elderly with Benign

Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol 75: 300304.

27. Day JJ, Freer CE, Dixon AK, Coni N, Hall LD, et al. (1990) Magnetic resonance

imaging of the brain and brain-stem in elderly patients with dizziness. Age

Ageing 19: 144150.

28. Blessing R, Strutz J, Beck C (1986) Epidemiology of benign paroxysmal

positional vertigo. Laryngol Rhinol Otol (Stuttg) 65: 455458.

29. Hajioff D, Barr-Hamilton RM, Colledge NR, Lewis SJ, Wilson JA (2002) Is

electronystagmography of diagnostic value in the elderly? Clin Otolaryngol

Allied Sci 27: 2731.

23. Evans JG (1990) Transient neurological dysfunction and risk of stroke in an

elderly English population: the different significance of vertigo and non-rotatory

dizziness. Age Ageing 19: 4349.

24. Cohen HS, Kimball KT, Stewart MG (2004) Benign paroxysmal positional

vertigo and comorbid conditions. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec 66: 11

15.

25. Maarsingh OR, Dros J, Schellevis FG, van Weert HC, Bindels PJ, et al. (2010)

Dizziness reported by elderly patients in family practice: prevalence, incidence,

and clinical characteristics. BMC Fam Pract 11: 2.

PLOS ONE | www.plosone.org

March 2013 | Volume 8 | Issue 3 | e58106

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- Test Bank ECGs Made Easy 5th Edition Barbara J AehlertDokumen10 halamanTest Bank ECGs Made Easy 5th Edition Barbara J AehlertErnest67% (3)

- RMO Clinical HandbookDokumen533 halamanRMO Clinical HandbookRicardo TBelum ada peringkat

- Case Study 101: Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm With Acute Kidney InjuryDokumen8 halamanCase Study 101: Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm With Acute Kidney InjuryPatricia Ann Nicole ReyesBelum ada peringkat

- Medical Negligence in Ghana Another Look at Asantekramo 1Dokumen3 halamanMedical Negligence in Ghana Another Look at Asantekramo 1SAMMY100% (1)

- Burden of Dizziness and Vertigo in The CommunityDokumen8 halamanBurden of Dizziness and Vertigo in The CommunityEcaterina ChiriacBelum ada peringkat

- Interviewing and Counseling The Dizzy Patient With Focus On Quality of LifeDokumen9 halamanInterviewing and Counseling The Dizzy Patient With Focus On Quality of LifeCribea AdmBelum ada peringkat

- Postictal Headache in South African Adult Patients With Generalised Epilepsy in A Tertiary Care Setting: A Cross-Sectional StudyDokumen7 halamanPostictal Headache in South African Adult Patients With Generalised Epilepsy in A Tertiary Care Setting: A Cross-Sectional StudyPerisha VeeraBelum ada peringkat

- Ahl N DepressionDokumen7 halamanAhl N DepressionDr Pavina RayamajhiBelum ada peringkat

- Review Article: Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo: An Integrated PerspectiveDokumen18 halamanReview Article: Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo: An Integrated PerspectivenurulmaulidyahidayatBelum ada peringkat

- Faktor PredisposisiDokumen29 halamanFaktor PredisposisiKim AntelBelum ada peringkat

- Dizziness 1 PDFDokumen7 halamanDizziness 1 PDFShruthi IyengarBelum ada peringkat

- Health 2016072214463557Dokumen10 halamanHealth 2016072214463557Rofi MarhendraBelum ada peringkat

- Correlates of General Quality of Life Are Different in Patients With Primary Insomnia As Compared To Patients With Insomnia and Psychiatric ComorbidityDokumen13 halamanCorrelates of General Quality of Life Are Different in Patients With Primary Insomnia As Compared To Patients With Insomnia and Psychiatric ComorbidityVictor CarrenoBelum ada peringkat

- Clinical Study: Vertigo in Children and Adolescents: Characteristics and OutcomeDokumen6 halamanClinical Study: Vertigo in Children and Adolescents: Characteristics and OutcomeC Leite HendriyBelum ada peringkat

- Postdural Puncture Headache and Epidural Blood Patch Use in Elderly PatientsDokumen5 halamanPostdural Puncture Headache and Epidural Blood Patch Use in Elderly PatientsJunwei XingBelum ada peringkat

- ANNALS DementiaDokumen16 halamanANNALS DementiaewbBelum ada peringkat

- Depersonalisation/derealisation Symptoms in Vestibular DiseaseDokumen7 halamanDepersonalisation/derealisation Symptoms in Vestibular DiseaseRobert WilliamsBelum ada peringkat

- Sleep Quality-NhsDokumen6 halamanSleep Quality-NhsKondang WarasBelum ada peringkat

- Cost MGT of DizzinessDokumen6 halamanCost MGT of Dizzinesszappo7919Belum ada peringkat

- Medi 94 E453Dokumen6 halamanMedi 94 E453ChyeunyesBelum ada peringkat

- HypertensiDokumen7 halamanHypertensizazaBelum ada peringkat

- BMJ Risk Fall On Neuro DiseaseDokumen17 halamanBMJ Risk Fall On Neuro DiseaseAmaliFaizBelum ada peringkat

- Status Epilepticus in Adults: A Study From Nigeria: SciencedirectDokumen6 halamanStatus Epilepticus in Adults: A Study From Nigeria: SciencedirectLuther ThengBelum ada peringkat

- Jurnal UtamaDokumen8 halamanJurnal UtamaUhti JahrotunisaBelum ada peringkat

- S 0035 1565915 PDFDokumen8 halamanS 0035 1565915 PDFSandu DidencuBelum ada peringkat

- Kurre 2012 - Gender Perceived Disability Anxiety Depression 1472-6815-12-2Dokumen12 halamanKurre 2012 - Gender Perceived Disability Anxiety Depression 1472-6815-12-2Ikhsan JohnsonBelum ada peringkat

- Life Quality of Patients Suffering Cerebral Stroke: Sidita Haxholli, Caterina Gruosso, Gennaro Rocco, Enzo RubertiDokumen10 halamanLife Quality of Patients Suffering Cerebral Stroke: Sidita Haxholli, Caterina Gruosso, Gennaro Rocco, Enzo RubertiijasrjournalBelum ada peringkat

- Agostini 2016 - The Prevention of EpilepsyDokumen2 halamanAgostini 2016 - The Prevention of EpilepsyMark CheongBelum ada peringkat

- Psychological Aspects in Chronic Renal Failure: Review RticleDokumen10 halamanPsychological Aspects in Chronic Renal Failure: Review RticleTry Febriani SiregarBelum ada peringkat

- Oa PDFDokumen7 halamanOa PDFFrandy HuangBelum ada peringkat

- Original Paper Comorbidity of Epilepsy and Depression in Al Husseini Teaching Hospital in Holy Kerbala /iraq in 2018Dokumen9 halamanOriginal Paper Comorbidity of Epilepsy and Depression in Al Husseini Teaching Hospital in Holy Kerbala /iraq in 2018sarhang talebaniBelum ada peringkat

- Research: Neurological Sequelae in Survivors of Cerebral MalariaDokumen9 halamanResearch: Neurological Sequelae in Survivors of Cerebral MalariaHervi LaksariBelum ada peringkat

- Aao HNSF - BPPVDokumen36 halamanAao HNSF - BPPVandiBelum ada peringkat

- Long-Term Cognitive Impairment After Critical Illness: Original ArticleDokumen11 halamanLong-Term Cognitive Impairment After Critical Illness: Original ArticleRendy ReventonBelum ada peringkat

- Stroke Research PaperDokumen4 halamanStroke Research Paperegx124k2100% (1)

- BAGIAN ILMU PENYAKIT SARAF Journal ReadingDokumen28 halamanBAGIAN ILMU PENYAKIT SARAF Journal ReadingKarelau KarniaBelum ada peringkat

- Assessment of Oropharyngeal Dysphagia in Patients With Parkinson Disease: Use of UltrasonographyDokumen7 halamanAssessment of Oropharyngeal Dysphagia in Patients With Parkinson Disease: Use of UltrasonographyTri Eka JuliantoBelum ada peringkat

- EB June1Dokumen7 halamanEB June1amiruddin_smartBelum ada peringkat

- Krijrano G. Cabañez Bsnursing Iii: Sen A, Capelli V, Husain M (February, 2018)Dokumen3 halamanKrijrano G. Cabañez Bsnursing Iii: Sen A, Capelli V, Husain M (February, 2018)ampalBelum ada peringkat

- Disorders Transition To Schizophrenia in Acute and Transient PsychoticDokumen8 halamanDisorders Transition To Schizophrenia in Acute and Transient PsychoticMuhammad Habibul IhsanBelum ada peringkat

- Sudden Sensorineural Hearing Loss Prognostic Factors: Dass Arjun, Goel Neha, Singhal Surinder K, Kapoor RaviDokumen11 halamanSudden Sensorineural Hearing Loss Prognostic Factors: Dass Arjun, Goel Neha, Singhal Surinder K, Kapoor RaviAnonymous Wijo8txBelum ada peringkat

- Dysphagia in Parkinson's Disease Improves With Vocal AugmentationDokumen7 halamanDysphagia in Parkinson's Disease Improves With Vocal Augmentationkhadidja BOUTOUILBelum ada peringkat

- Status Epilepticus in AdultsDokumen3 halamanStatus Epilepticus in AdultsampalBelum ada peringkat

- PPPD Is On A Spectrum in The General PopulationDokumen11 halamanPPPD Is On A Spectrum in The General PopulationJuan Hernández GarcíaBelum ada peringkat

- Epilepsy & Behavior: Shanna M. Guilfoyle, Sally Monahan, Cindy Wesolowski, Avani C. ModiDokumen6 halamanEpilepsy & Behavior: Shanna M. Guilfoyle, Sally Monahan, Cindy Wesolowski, Avani C. ModiJhonny BatongBelum ada peringkat

- Clinical Review: Diagnosis and Treatment of Low Back PainDokumen5 halamanClinical Review: Diagnosis and Treatment of Low Back PainAulya Adha DiniBelum ada peringkat

- Efficacy and Safety of Pallidal Stimulation in Primary Dystonia: Results of The Spanish Multicentric StudyDokumen16 halamanEfficacy and Safety of Pallidal Stimulation in Primary Dystonia: Results of The Spanish Multicentric Studypatry_ordexBelum ada peringkat

- Self-Management in Older Patients With Chronic Illness: ResearchpaperDokumen11 halamanSelf-Management in Older Patients With Chronic Illness: ResearchpaperAlberto MeroBelum ada peringkat

- Epileptic Seizures in Critically Ill Patients: Diagnosis, Management, and OutcomesDokumen3 halamanEpileptic Seizures in Critically Ill Patients: Diagnosis, Management, and OutcomesDobson Flores AparicioBelum ada peringkat

- Classification and Clinical Features of Headache Disorders in Pakistan: A Retrospective Review of Clinical DataDokumen8 halamanClassification and Clinical Features of Headache Disorders in Pakistan: A Retrospective Review of Clinical DatarikramBelum ada peringkat

- Jurnal Internasional PDFDokumen7 halamanJurnal Internasional PDFGabriela FierreBelum ada peringkat

- JCN 10 236Dokumen8 halamanJCN 10 236viyolaazzahraBelum ada peringkat

- Changing Profile of 7,519 Neurologic Outpatients Evaluated Over 20 YearsDokumen10 halamanChanging Profile of 7,519 Neurologic Outpatients Evaluated Over 20 YearsNicole AguilarBelum ada peringkat

- 3.the Efficient Dizziness History and ExamDokumen12 halaman3.the Efficient Dizziness History and ExamCribea AdmBelum ada peringkat

- Life Expectancy and Years of Potential Life Lost in People Wit 2023 EClinicaDokumen18 halamanLife Expectancy and Years of Potential Life Lost in People Wit 2023 EClinicaronaldquezada038Belum ada peringkat

- Epilepsy: New Advances: Journal ReadingDokumen29 halamanEpilepsy: New Advances: Journal Readingastra yudhaTagamawanBelum ada peringkat

- Chaturvedi 2009Dokumen7 halamanChaturvedi 2009Sonal AgarwalBelum ada peringkat

- Original Paper: Factors That Impact Caregivers of Patients With SchizophreniaDokumen10 halamanOriginal Paper: Factors That Impact Caregivers of Patients With SchizophreniaMichaelus1Belum ada peringkat

- ADHD Syndrome and Tic Disorders Two Sides of The Same CoinDokumen11 halamanADHD Syndrome and Tic Disorders Two Sides of The Same CoinEve AthanasekouBelum ada peringkat

- Prader WilliDokumen15 halamanPrader WilliGVHHBelum ada peringkat

- Prevalence and Recognition of Geriatric Syndromes in An Outpatient Clinic at A Tertiary Care Hospital of ThailandDokumen5 halamanPrevalence and Recognition of Geriatric Syndromes in An Outpatient Clinic at A Tertiary Care Hospital of ThailandYuliana Eka SintaBelum ada peringkat

- Treatment–Refractory Schizophrenia: A Clinical ConundrumDari EverandTreatment–Refractory Schizophrenia: A Clinical ConundrumPeter F. BuckleyBelum ada peringkat

- Inpatient Geriatric Psychiatry: Optimum Care, Emerging Limitations, and Realistic GoalsDari EverandInpatient Geriatric Psychiatry: Optimum Care, Emerging Limitations, and Realistic GoalsHoward H. FennBelum ada peringkat

- 5 X 5 Rmnch+aDokumen2 halaman5 X 5 Rmnch+aManish Chandra Prabhakar0% (1)

- Guidelines For Maternal Death Surveillance & ResponseDokumen148 halamanGuidelines For Maternal Death Surveillance & ResponseManish Chandra Prabhakar100% (3)

- IMA - Rules and Bye-Laws, 2019 PDFDokumen100 halamanIMA - Rules and Bye-Laws, 2019 PDFManish Chandra PrabhakarBelum ada peringkat

- National Guidelines For Screening of Hypothyroidism During PregnancyDokumen48 halamanNational Guidelines For Screening of Hypothyroidism During PregnancyManish Chandra PrabhakarBelum ada peringkat

- Concept Origin Development of Social SecuritiesDokumen48 halamanConcept Origin Development of Social SecuritiesManish Chandra PrabhakarBelum ada peringkat

- Diabetes Care Guidelines - ADA 2014Dokumen9 halamanDiabetes Care Guidelines - ADA 2014Manish Chandra PrabhakarBelum ada peringkat

- Social Security in India - Historical Development and Labour PolicyDokumen29 halamanSocial Security in India - Historical Development and Labour PolicyManish Chandra Prabhakar100% (1)

- NEET PG 2012 Entrance Examination and PatternDokumen4 halamanNEET PG 2012 Entrance Examination and PatternManish Chandra PrabhakarBelum ada peringkat

- A Small Truth To Make Life 100%Dokumen9 halamanA Small Truth To Make Life 100%qistina16Belum ada peringkat

- Sri Sri Durga Saptshati (Sanskrit - Hindi)Dokumen241 halamanSri Sri Durga Saptshati (Sanskrit - Hindi)Mukesh K. Agrawal62% (13)

- Manish Chandra Prabhakar Mgims: 1 Reference-Harrison's Internal Medicine 18th EditionDokumen79 halamanManish Chandra Prabhakar Mgims: 1 Reference-Harrison's Internal Medicine 18th EditionManish Chandra PrabhakarBelum ada peringkat

- NEET PG 2013 Information Booklet FINALDokumen88 halamanNEET PG 2013 Information Booklet FINALManish Chandra PrabhakarBelum ada peringkat

- Stipend Increased For Intern Doctors at MUHS NashikDokumen2 halamanStipend Increased For Intern Doctors at MUHS NashikManish Chandra Prabhakar100% (1)

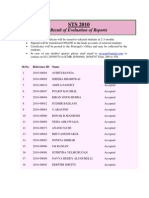

- Icmr Sts Result 2011Dokumen32 halamanIcmr Sts Result 2011Manish Chandra PrabhakarBelum ada peringkat

- ICMR STS 2010 Report Submission ResultsDokumen27 halamanICMR STS 2010 Report Submission ResultsManish Chandra PrabhakarBelum ada peringkat

- How To WriteDokumen13 halamanHow To WriteSebastian Quiroz FloresBelum ada peringkat

- Dizziness in The Elderly: Steven Zweig, MD Family and Community Medicine MU School of MedicineDokumen34 halamanDizziness in The Elderly: Steven Zweig, MD Family and Community Medicine MU School of MedicineManish Chandra PrabhakarBelum ada peringkat

- The Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS) (2) 091621Dokumen475 halamanThe Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS) (2) 091621jb_uspuBelum ada peringkat

- HydrotherapyDokumen40 halamanHydrotherapyThopu UmamaheswariBelum ada peringkat

- Assessment of HearingDokumen51 halamanAssessment of HearingSwetha PasupuletiBelum ada peringkat

- HemostasisDokumen5 halamanHemostasisPadmavathi C100% (1)

- Effectiveness of Communication Board On Level of Satisfaction Over Communication Among Mechanically Venitlated PatientsDokumen6 halamanEffectiveness of Communication Board On Level of Satisfaction Over Communication Among Mechanically Venitlated PatientsInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyBelum ada peringkat

- Arthrogryposis Multiplex Congenita-Dr S P DasDokumen7 halamanArthrogryposis Multiplex Congenita-Dr S P DasSheel GuptaBelum ada peringkat

- Capstone ProjectDokumen11 halamanCapstone ProjectDave Matthew LibiranBelum ada peringkat

- Appendicitis Case StudyDokumen10 halamanAppendicitis Case StudyMarie JoannBelum ada peringkat

- Clinical Evaluation FormDokumen1 halamanClinical Evaluation FormAndalBelum ada peringkat

- NCP GRAND CASE PRE C Nursing ProblemsDokumen9 halamanNCP GRAND CASE PRE C Nursing ProblemsAngie Mandeoya100% (1)

- Panduan Troli EmergencyDokumen3 halamanPanduan Troli EmergencyTukiyemBelum ada peringkat

- Children's Types by Douglas M. Borland, M.B., CH.B (Glasgow) Presented by Sylvain CazaletDokumen42 halamanChildren's Types by Douglas M. Borland, M.B., CH.B (Glasgow) Presented by Sylvain Cazaletmadhavkrishna809100% (2)

- Interactions Between Antigen and AntibodyDokumen25 halamanInteractions Between Antigen and AntibodyvmshanesBelum ada peringkat

- Crisis Management Covid 19Dokumen22 halamanCrisis Management Covid 19jon elleBelum ada peringkat

- SB 3 Flu VaccineDokumen2 halamanSB 3 Flu VaccineBIANNE KATRINA GASAGASBelum ada peringkat

- TestDokumen4 halamanTestmelodyfathiBelum ada peringkat

- Nnyy3999 PDFDokumen2 halamanNnyy3999 PDFAshwin SagarBelum ada peringkat

- Livro Robbins PathologyDokumen18 halamanLivro Robbins Pathologyernestooliveira50% (2)

- Practical Guide To Insulin Therapy in Type 2 Diabetes: January 2011Dokumen91 halamanPractical Guide To Insulin Therapy in Type 2 Diabetes: January 2011leeyie22Belum ada peringkat

- Introduction History Examination (Prosthodontics)Dokumen37 halamanIntroduction History Examination (Prosthodontics)sarah0% (1)

- Health Declaration FormDokumen1 halamanHealth Declaration Formargie joy marieBelum ada peringkat

- NARPAA E-Class Module 3 - Historical Definitions of AutismDokumen19 halamanNARPAA E-Class Module 3 - Historical Definitions of AutismnarpaaBelum ada peringkat

- Humoral ImmunityDokumen86 halamanHumoral ImmunitySinthiya KanesaratnamBelum ada peringkat

- Cholesteatoma PDFDokumen28 halamanCholesteatoma PDFazadutBelum ada peringkat

- Greene & Manfredini 2023 - Overtreatment Successes - 230709 - 135204Dokumen11 halamanGreene & Manfredini 2023 - Overtreatment Successes - 230709 - 135204Abigail HernándezBelum ada peringkat

- ShoccckDokumen23 halamanShoccckHainey GayleBelum ada peringkat