Torts Case Digest

Diunggah oleh

Jonna Icao Silva DelacruzDeskripsi Asli:

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Torts Case Digest

Diunggah oleh

Jonna Icao Silva DelacruzHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

[G.R. No. 118192. October 23, 1997] PRO LINE SPORTS CENTER, INC.

, and QUESTOR CORPORATION, petitioners, vs. COURT OF APPEALS, UNIVERSAL ATHLETICS INDUSTRIAL PRODUCTS, INC., and MONICO SEHWANI, respondents. After the prosecution rested its case, Sehwani filed a demurrer to evidence arguing that the act of selling the manufactured goods was an essential and constitutive element of the crime of unfair competition under Art. 189 of the Revised Penal Code, and the prosecution was not able to prove that he sold the products. In its Order of 12 January 1981 the trial court granted the demurrer and dismissed the charge against Sehwani. The existence of probable cause for unfair competition by UNIVERSAL is derivable from the facts and circumstances of the case. The affidavit of Graciano Lacanaria, a former employee of UNIVERSAL, attesting to the illegal sale and manufacture of "Spalding" balls and seized "Spalding" products and instruments from UNIVERSAL's factory was sufficient prima facie evidence to warrant the prosecution of private respondents. That a corporation other than the certified owner of the trademark is engaged in the unauthorized manufacture of products bearing the same trademark engenders a reasonable belief that a criminal offense for unfair competition is being committed. Petitioners PRO LINE and QUESTOR could not have been moved by legal malice in instituting the criminal complaint for unfair competition which led to the filing of the Information against Sehwani. Malice is an inexcusable intent to injure, oppress, vex, annoy or humiliate. We cannot conclude that petitioners were impelled solely by a desire to inflict needless and unjustified vexation and injury on UNIVERSAL's business interests. A resort to judicial processes is not per se evidence of ill will upon which a claim for damages may be based. A contrary rule would discourage peaceful recourse to the courts of justice and induce resort to methods less than legal, and perhaps even violent. We are more disposed, under the circumstances, to hold that PRO LINE as the authorized agent of QUESTOR exercised sound judgment in taking the necessary legal steps to safeguard the interest of its principal with respect to the trademark in question. If the process resulted in the closure and padlocking of UNIVERSAL's factory and the cessation of its business operations, these were unavoidable consequences of petitioners' valid and lawful exercise of their right. One who makes use of his own legal right does no injury. Qui jure suo utitur nullum damnum facit. If damage results from a person's exercising his legal rights, it is damnum absque injuria. Admittedly, UNIVERSAL incurred expenses and other costs in defending itself from the accusation. But, as Chief Justice Fernando would put it, "the expenses and annoyance of litigation form part of the social burden of living in a society which seeks to attain social control through law." Thus we see no cogent reason for the award of damages, exorbitant as it may seem, in favor of UNIVERSAL. To do so would be to arbitrarily impose a penalty on petitioners' right to litigate. The criminal complaint for unfair competition, including all other legal remedies incidental thereto, was initiated by petitioners in their honest belief that the charge was meritorious. For indeed it was. The law brands business practices which are unfair, unjust or deceitful not only as contrary to public policy but also as inimical to private interests. In the instant case, we find quite aberrant Sehwani's reason for the manufacture of 1,200 "Spalding" balls, i.e., the pending application for trademark registration of UNIVERSAL with the Patent Office, when viewed in the light of his admission that the application for registration with the Patent Office was filed on 20 February 1981, a good nine (9) days after the goods were confiscated by the NBI. This apparently was an afterthought but nonetheless too late a remedy. Be that as it may, what is essential for registrability is proof of actual use in commerce for at least sixty (60) days and not the capability to manufacture and distribute samples of the product to clients. Arguably, respondents' act may constitute unfair competition even if the element of selling has not been proved. To hold that the act of selling is an indispensable element of the crime of unfair competition is illogical because if the law punishes the seller of imitation goods, then with more reason should the law penalize the manufacturer. In U. S. v. Manuel, the Court ruled that the test of unfair competition is whether certain goods have been intentionally clothed with an appearance which is likely to deceive the ordinary purchasers exercising ordinary care. In this case, it was observed by the Minister of Justice that the manufacture of the "Spalding" balls was obviously done to deceive would-be buyers. The projected sale would have pushed through were it not for the timely seizure of the goods made by the NBI. That there was intent to sell or distribute the product to the public cannot also be disputed given the number of goods manufactured and the nature of the machinery and other equipment installed in the factory. IN-N-OUT BURGER, INC, vs SEHWANI, INCORPORATED AND/OR BENITAS FRITES, INC.,

G.R. No. 179127 December 24, 2008 The essential elements of an action for unfair competition are (1) confusing similarity in the general appearance of the goods and (2) intent to deceive the public and defraud a competitor. The confusing similarity may or may not result from similarity in the marks, but may result from other external factors in the packaging or presentation of the goods. The intent to deceive and defraud may be inferred from the similarity of the appearance of the goods as offered for sale to the public. Actual fraudulent intent need not be shown. With such finding, the award of damages in favor of petitioner is but proper. This is in accordance with Section 168.4 of the Intellectual Property Code, which provides that the remedies under Sections 156, 157 and 161 for infringement shall apply mutatis mutandis to unfair competition. The remedies provided under Section 156 include the right to damages, to be computed in the following manner: Section 156. Actions, and Damages and Injunction for Infringement.--156.1 The owner of a registered mark may recover damages from any person who infringes his rights, and the measure of the damages suffered shall be either the reasonable profit which the complaining party would have made, had the defendant not infringed his rights, or the profit which the defendant actually made out of the infringement, or in the event such measure of damages cannot be readily ascertained with reasonable certainty, then the court may award as damages a reasonable percentage based upon the amount of gross sales of the defendant or the value of the services in connection with which the mark or trade name was used in the infringement of the rights of the complaining party. G.R. No. 154342, Mighty Corporation v. E & J. Gallo Winery, July 14, 2004 The Court ordered the dismissal of the complaint for trademark infringement and unfair competition by E & J Gallo Winery against petitioner manufacturer and seller of cigarettes using the Gallo trademark, holding, among others, that GALLO cannot be considered a well-known mark within the contemplation and protection of the Paris Convention in this case since wines and cigarettes are not identical or similar goods.

COFFEE PARTNERS, INC., VS. SAN FRANCISCO COFFEE & ROASTERY, INC., G.R. No. 169504, March 3, 2010 Petitioner Coffee Partners, Inc. is a local corporation engaged in the business of establishing and maintaining coffee shops in the country. It registered with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) in January 2001. It has a franchise agreement with Coffee Partners Ltd. (CPL), a business entity organized and existing under the laws of British Virgin Islands, for a non-exclusive right to operate coffee shops in the Philippines using trademarks designed by CPL such as SAN FRANCISCO COFFEE. Respondent is a local corporation engaged in the wholesale and retail sale of coffee. It registered with the SEC in May 1995. It registered the business name SAN FRANCISCO COFFEE & ROASTERY, INC. with the Department of Trade and Industry (DTI) in June 1995. Respondent had since built a customer base that included Figaro Company, Tagaytay Highlands, Fat Willys, and other coffee companies. In 1998, respondent formed a joint venture company with Boyd Coffee USA under the company name Boyd Coffee Company Philippines, Inc. (BCCPI). BCCPI engaged in the processing, roasting, and wholesale selling of coffee. Respondent later embarked on a project study of setting up coffee carts in malls and other commercial establishments in Metro Manila. In June 2001, respondent discovered that petitioner was about to open a coffee shop under the name SAN FRANCISCO COFFEE in Libis, Quezon City. According to respondent, petitioners shop caused confusion in the minds of the public as it bore a similar name and it also engaged in the business of selling coffee. Respondent sent a letter to petitioner demanding that the latter stop using the name SAN FRANCISCO COFFEE. Respondent also filed a complaint with the Bureau of Legal Affairs-Intellectual Property Office (BLA-IPO) for infringement and/or unfair competition with claims for damages. In its answer, petitioner denied the allegations in the complaint. Petitioner alleged it filed with the Intellectual Property Office (IPO) applications for registration of the mark SAN FRANCISCO COFFEE & DEVICE for class 42 in 1999 and for class 35 in 2000. Petitioner maintained its mark could not be confused with respondents trade name because of the notable distinctions in their appearances. Petitioner argued respondent stopped operating under the trade

name SAN FRANCISCO COFFEE when it formed a joint venture with Boyd Coffee USA. Petitioner contended respondent did not cite any specific acts that would lead one to believe petitioner had, through fraudulent means, passed off its mark as that of respondent or that it had diverted business away from respondent. The sole issue is whether petitioners use of the trademark SAN FRANCISCO COFFEE constitutes infringement of respondents trade name SAN FRANCISCO COFFEE & ROASTERY, INC., even if the trade name is not registered with the Intellectual Property Office (IPO). The BLA-IPO also held that respondent did not abandon the use of its trade name as substantial evidence indicated respondent continuously used its trade name in connection with the purpose for which it was organized. It found that although respondent was no longer involved in blending, roasting, and distribution of coffee because of the creation of BCCPI, it continued making plans and doing research on the retailing of coffee and the setting up of coffee carts. The BLA-IPO ruled that for abandonment to exist, the disuse must be permanent, intentional, and voluntary. The BLA-IPO also dismissed respondents claim of actual damages because its claims of profit loss were based on mere assumptions as respondent had not even started the operation of its coffee carts. The BLA-IPO likewise dismissed respondents claim of moral damages, but granted its claim of attorneys fees. In its 22 October 2003 Decision, the ODG-IPO reversed the BLA-IPO. It ruled that petitioners use of the trademark SAN FRANCISCO COFFEE did not infringe on respondent's trade name. The ODG-IPO found that respondent had stopped using its trade name after it entered into a joint venture with Boyd Coffee USA in 1998 while petitioner continuously used the trademark since June 2001 when it opened its first coffee shop in Libis, Quezon City. It ruled that between a subsequent user of a trade name in good faith and a prior user who had stopped using such trade name, it would be inequitable to rule in favor of the latter. Clearly, a trade name need not be registered with the IPO before an infringement suit may be filed by its owner against the owner of an infringing trademark. All that is required is that the trade name is previously used in trade or commerce in the Philippines. APPLYING EITHER THE DOMINANCY TEST OR THE HOLISTIC TEST, PETITIONERS SAN FRANCISCO COFFEE TRADEMARK IS A CLEAR INFRINGEMENT OF RESPONDENTS SAN FRANCISCO COFFEE & ROASTERY, INC. TRADE NAME. THE DESCRIPTIVE WORDS SAN FRANCISCO COFFEE ARE PRECISELY THE DOMINANT FEATURES OF RESPONDENTS TRADE NAME. PETITIONER AND RESPONDENT ARE ENGAGED IN THE SAME BUSINESS OF SELLING COFFEE, WHETHER WHOLESALE OR RETAIL. THE LIKELIHOOD OF CONFUSION IS HIGHER IN CASES WHERE THE BUSINESS OF ONE CORPORATION IS THE SAME OR SUBSTANTIALLY THE SAME AS THAT OF ANOTHER CORPORATION. IN THIS CASE, THE CONSUMING PUBLIC WILL LIKELY BE CONFUSED AS TO THE SOURCE OF THE COFFEE BEING SOLD AT PETITIONERS COFFEE SHOPS. PETITIONERS ARGUMENT THAT SAN FRANCISCO IS JUST A PROPER NAME REFERRING TO THE FAMOUS CITY IN CALIFORNIA AND THAT COFFEE IS SIMPLY A GENERIC TERM, IS UNTENABLE. RESPONDENT HAS ACQUIRED AN EXCLUSIVE RIGHT TO THE USE OF THE TRADE NAME SAN FRANCISCO COFFEE & ROASTERY, INC. SINCE THE REGISTRATION OF THE BUSINESS NAME WITH THE DTI IN 1995. THUS, RESPONDENTS USE OF ITS TRADE NAME FROM THEN ON MUST BE FREE FROM ANY INFRINGEMENT BY SIMILARITY. OF COURSE, THIS DOES NOT MEAN THAT RESPONDENT HAS EXCLUSIVE USE OF THE GEOGRAPHIC WORD SAN FRANCISCO OR THE GENERIC WORD COFFEE. GEOGRAPHIC OR GENERIC WORDS ARE NOT, PER SE, SUBJECT TO EXCLUSIVE APPROPRIATION. IT IS ONLY THE COMBINATION OF THE WORDS SAN FRANCISCO COFFEE, WHICH IS RESPONDENTS TRADE NAME IN ITS COFFEE BUSINESS, THAT IS PROTECTED AGAINST INFRINGEMENT ON MATTERS RELATED TO THE COFFEE BUSINESS TO AVOID CONFUSING OR DECEIVING THE PUBLIC. THIS COURT IS NOT JUST A COURT OF LAW, BUT ALSO OF EQUITY. WE CANNOT ALLOW PETITIONER TO PROFIT BY THE NAME AND REPUTATION SO FAR BUILT BY RESPONDENT WITHOUT RUNNING AFOUL OF THE BASIC DEMANDS OF FAIR PLAY. NOT ONLY THE LAW BUT EQUITY CONSIDERATIONS HOLD PETITIONER LIABLE FOR INFRINGEMENT OF RESPONDENTS TRADE NAME.

SOCIETE DES PRODUITS NESTLE, S.A., vs. MARTIN T. DY, JR G.R. No. 172276 August 8, 2010

Facts: Petitioner Societe Des Produits Nestle, S.A. (Nestle) is a foreign corporation organized under the laws of Switzerland. It manufactures food products and beverages. As evidenced by Certificate of Registration No. R-14621 issued on 7 April 1969 by the then Bureau of Patents, Trademarks and Technology Transfer, Nestle owns the NAN trademark for its line of infant powdered milk products, consisting of PRE-NAN, NAN-H.A., NAN-1, and NAN-2. NAN is classified under Class 6 diatetic preparations for infant feeding. Nestle distributes and sells its NAN milk products all over the Philippines. It has been investing tremendous amounts of resources to train its sales force and to promote the NAN milk products through advertisements and press releases. Dy, Jr. owns 5M Enterprises. He imports Sunny Boy powdered milk from Australia and repacks the powdered milk into three sizes of plastic packs bearing the name NANNY. The packs weigh 80, 180 and 450 grams and are sold for P8.90, P17.50 and P39.90, respectively. NANNY is is also classified under Class 6 full cream milk for adults in [sic] all ages. Dy, Jr. distributes and sells the powdered milk in Dumaguete, Negros Oriental, Cagayan de Oro, and parts of Mindanao. In a letter dated 1 August 1985, Nestle requested Dy, Jr. to refrain from using NANNY and to undertake that he would stop infringing the NAN trademark. Dy, Jr. did not act on Nestles request. On 1 March 1990, Nestle filed before the RTC, Judicial Region 7, Branch 31, Dumaguete City, a complaint against Dy, Jr. for infringement. Dy, Jr. filed a motion to dismiss alleging that the complaint did not state a cause of action. In its 4 June 1990 order, the trial court dismissed the complaint. Nestle appealed the 4 June 1990 order to the Court of Appeals. In its 16 February 1993 Resolution, the Court of Appeals set aside the 4 June 1990 order and remanded the case to the trial court for further proceedings. Pursuant to Supreme Court Administrative Order No. 113-95, Nestle filed with the trial court a motion to transfer the case to the RTC, Judicial Region 7, Branch 9, Cebu City, which was designated as a special court for intellectual property rights.

Issue: Is Mr. Dy, Jr. liable of infringement? Ruling: Applying the dominancy test in the present case, the Court finds that NANNY is confusingly similar to NAN. NAN is the prevalent feature of Nestles line of infant powdered milk products. It is written in bold letters and used in all products. The line consists of PRE-NAN, NAN-H.A., NAN-1, and NAN-2. Clearly, NANNY contains the prevalent feature NAN. The first three letters of NANNY are exactly the same as the letters of NAN. When NAN and NANNY are pronounced, the aural effect is confusingly similar. The Court agrees with the lower courts that there are differences between NAN and NANNY: (1) NAN is intended for infants while NANNY is intended for children past their infancy and for adults; and (2) NAN is more expensive than NANNY. However, as the registered owner of the NAN mark, Nestle should be free to use its mark on similar products, in different segments of the market, and at different price levels. In McDonalds Corporation v. L.C. BigMak Burger, Inc., the Court held that the scope of protection afforded to registered

trademark owners extends to market areas that are the normal expansion of business: Even respondents use of the Big Mak mark on non-hamburger food products cannot excuse their infringement of petitioners registered mark, otherwise registered marks will lose their protection under the law. The registered trademark owner may use his mark on the same or similar products, in different segments of the market, and at different price levels depending on variations of the products for specific segments of the market. The Court has recognized that the registered trademark owner enjoys protection in product and market areas that are the normal potential expansion of his business. Thus, the Court has declared: Modern law recognizes that the protection to which the owner of a trademark is entitled is not limited to guarding his goods or business from actual market competition with identical or similar products of the parties, but extends to all cases in which the use by a junior appropriator of a trade-mark or trade-name is likely to lead to a confusion of source, as where prospective purchasers would be misled into thinking that the complaining party has extended his business into the field (see 148 ALR 56 et sq; 53 Am. Jur. 576) or is in any way connected with the activities of the infringer; or when it forestalls the normal potential expansion of his business (v. 148 ALR, 77, 84; 52 Am. Jur. 576, 577).

SONY COMPUTER ENTERTAINMENT, INC., vs Super Green G.R. No. 161823 March 22, 2007 Facts: The case stemmed from the complaint filed with the National Bureau of Investigation (NBI) by petitioner Sony Computer Entertainment, Inc., against respondent Supergreen, Incorporated. The NBI found that respondent engaged in the reproduction and distribution of counterfeit PlayStation game software, consoles and accessories in violation of Sony Computers intellectual property rights. Ruling: Nonetheless, we agree with petitioner that this case involves a transitory or continuing offense of unfair competition under Section 168 of Republic Act No. 8293, which provides, SEC. 168. Unfair Competition, Rights, Regulation and Remedies. 168.2. Any person who shall employ deception or any other means contrary to good faith by which he shall pass off the goods manufactured by him or in which he deals, or his business, or services for those of the one having established such goodwill, or who shall commit any acts calculated to produce said result, shall be guilty of unfair competition, and shall be subject to an action therefor. 168.3. In particular, and without in any way limiting the scope of protection against unfair competition, the following shall be deemed guilty of unfair competition: (a) Any person, who is selling his goods and gives them the general appearance of goods of another manufacturer or dealer, either as to the goods themselves or in the wrapping of the packages in which they are contained, or the devices or words thereon, or in any other feature of their appearance, which would be likely to influence purchasers to believe that the goods offered are those of a manufacturer or dealer, other

than theactual manufacturer or dealer, or who otherwise clothes the goods with such appearance as shall deceive the public and defraud another of his legitimate trade, or any subsequent vendor of such goods or any agent of anyvendor engaged in selling such goods with a like purpose; (b) Any person who by any artifice, or device, or who employs any other means calculated to induce the false belief that such person is offering the services of another who has identified such services in the mind of the public; or (c) Any person who shall make any false statement in the course of trade or who shall commit any other act contrary to good faith of a nature calculated to discredit the goods, business or services of another. Pertinent too is Article 189 (1) of the Revised Penal Code that enumerates the elements of unfair competition, to wit: (a) That the offender gives his goods the general appearanceof the goods of another manufacturer or dealer; (b) That the general appearance is shown in the (1) goods themselves, or in the (2) wrappingof their packages, or in the (3) device or wordstherein, or in (4) any other featureof their appearance; (c) That the offender offersto sell or sells those goods or gives other persons a chance or opportunity to do the same with a like purpose; and (d) That there is actual intent to deceivethe public or defraud a competitor. Respondents imitation of the general appearance of petitioners goods was done allegedly in Cavite. It sold the goods allegedly in Mandaluyong City, Metro Manila. The alleged acts would constitute a transitory or continuing offense. Thus, clearly, under Section 2 (b) of Rule 126, Section 168 of Rep. Act No. 8293 and Article 189 (1) of the Revised Penal Code, petitioner may apply for a search warrant in any court where any element of the alleged offense was committed, including any of the courts within the National Capital Region (Metro Manila).

SUPERIOR COMMERCIAL ENTERPRISES, INC., vs. KUNNAN ENTERPRISES LTD. AND SPORTS CONCEPT & DISTRIBUTOR, INC., G.R. No. 169974, April 20, 2010 Facts: On February 23, 1993, SUPERIOR filed a complaint for trademark infringement and unfair competition with preliminary injunction against KUNNAN and SPORTS CONCEPT with the RTC, docketed as Civil Case No. Q-93014888. In support of its complaint, SUPERIOR first claimed to be the owner of the trademarks, trading styles, company names and business names KENNEX, KENNEX & DEVICE, PRO KENNEX and PRO-KENNEX (disputed trademarks). Second, it also asserted its prior use of these trademarks, presenting as evidence of ownership the Principal and Supplemental Registrations of these trademarks in its name. Third, SUPERIOR also alleged that it extensively sold and advertised sporting goods and products covered by its trademark

registrations. Finally, SUPERIOR presented as evidence of its ownership of the disputed trademarks the preambular clause of the Distributorship Agreement dated October 1, 1982 (Distributorship Agreement) it executed with KUNNAN, which states: Whereas, KUNNAN intends to acquire the ownership of KENNEX trademark registered by the [sic] Superior in the Philippines. Whereas, the [sic] Superior is desirous of having been appointed [sic] as the sole distributor by KUNNAN in the territory of the Philippines. [Emphasis supplied.] In its defense, KUNNAN disputed SUPERIORs claim of ownership and maintained that SUPERIOR as mere distributor from October 6, 1982 until December 31, 1991 fraudulently registered the trademarks in its name. KUNNAN alleged that it was incorporated in 1972, under the name KENNEX Sports Corporation for the purpose of manufacturing and selling sportswear and sports equipment; it commercially marketed its products in different countries, including the Philippines since 1972. It created and first used PRO KENNEX, derived from its original corporate name, as a distinctive trademark for its products in 1976. KUNNAN also alleged that it registered the PRO KENNEX trademark not only in the Philippines but also in 31 other countries, and widely promoted the KENNEX and PRO KENNEX trademarks through worldwide advertisements in print media and sponsorships of known tennis players. On October 1, 1982, after the expiration of its initial distributorship agreement with another company, KUNNAN appointed SUPERIOR as its exclusive distributor in the Philippines under a Distributorship Agreement whose pertinent provisions state: Whereas, KUNNAN intends to acquire ownership of KENNEX trademark registered by the Superior in the Philippines. Whereas, the Superior is desirous of having been appointed [sic] as the sole distributor by KUNNAN in the territory of the Philippines. Now, therefore, the parties hereto agree as follows: 1. KUNNAN in accordance with this Agreement, will appoint the sole distributorship right to Superior in the Philippines, and this Agreement could be renewed with the consent of both parties upon the time of expiration. 2. The Superior, in accordance with this Agreement, shall assign the ownership of KENNEX trademark, under the registration of Patent Certificate No. 4730 dated 23 May 1980 to KUNNAN on the effects [sic] of its ten (10) years contract of distributorship, and it is required that the ownership of the said trademark shall be genuine, complete as a whole and without any defects. On December 3, 1991, upon the termination of its distributorship agreement with SUPERIOR, KUNNAN appointed SPORTS CONCEPT as its new distributor. Subsequently, KUNNAN also caused the publication of a Notice and Warning in the Manila Bulletins January 29, 1993 issue, stating that (1) it is the owner of the disputed trademarks; (2) it terminated its Distributorship Agreement with SUPERIOR; and (3) it appointed SPORTS CONCEPT as its exclusive distributor. This notice prompted SUPERIOR to file its Complaint for Infringement of Trademark and Unfair Competition with Preliminary Injunction against KUNNAN.

The IPO and CA Rulings

there being sufficient evidence to prove that the Petitioner-Opposer (KUNNAN) is the prior user and owner of the trademark PRO-KENNEX, the consolidated Petitions for Cancellation and the Notices of Opposition are herebyGRANTED. Consequently, the trademark PRO-KENNEX bearing Registration Nos. 41032, 40326, 39254, 4730, 49998 for the mark PRO-KENNEX issued in favor of Superior Commercial Enterprises, Inc., herein Respondent-Registrant under the Principal Register and SR No. 6663 are hereby CANCELLED. Accordingly, trademark application Nos. 84565 and 84566, likewise for the registration of the mark PRO-KENNEX are hereby REJECTED. It dismissed SUPERIORs Complaint for Infringement of Trademark and Unfair Competition with Preliminary Injunction on the ground that SUPERIOR failed to establish by preponderance of evidence its claim of ownership over the KENNEX and PRO KENNEX trademarks. The CA found the Certificates of Principal and Supplemental Registrations and the whereas clause of the Distributorship Agreement insufficient to support SUPERIORs claim of ownership over the disputed trademarks. The CA stressed that SUPERIORs possession of the aforementioned Certificates of Principal Registration does not conclusively establish its ownership of the disputed trademarks as dominion over trademarks is not acquired by the fact of registration alone; at best, registration merely raises a presumption of ownership that can be rebutted by contrary evidence. The CA further emphasized that the Certificates of Supplemental Registration issued in SUPERIORs name do not even enjoy the presumption of ownership accorded to registration in the principal register; it does not amount to a prima facie evidence of the validity of registration or of the registrants exclusive right to use the trademarks in connection with the goods, business, or services specified in the certificate From jurisprudence, unfair competition has been defined as the passing off (or palming off) or attempting to pass off upon the public of the goods or business of one person as the goods or business of another with the end and probable effect of deceiving the public. The essential elements of unfair competition are (1) confusing similarity in the general appearance of the goods; and (2) intent to deceive the public and defraud a competitor. Jurisprudence also formulated the following true test of unfair competition: whether the acts of the defendant have the intent of deceiving or are calculated to deceive the ordinary buyer making his purchases under the ordinary conditions of the particular trade to which the controversy relates. One of the essential requisites in an action to restrain unfair competition is proof of fraud; the intent to deceive, actual or probable must be shown before the right to recover can exist. In the present case, no evidence exists showing that KUNNAN ever attempted to pass off the goods it sold (i.e. sportswear, sporting goods and equipment) as those of SUPERIOR. In addition, there is no evidence of bad faith or fraud imputable to KUNNAN in using the disputed trademarks. Specifically, SUPERIOR failed to adduce any evidence to show that KUNNAN by the above-cited acts intended to deceive the public as to the identity of the goods sold or of the manufacturer of the goods sold. In McDonalds Corporation v. L.C. Big Mak Burger, Inc.,we held that there can be trademark infringement without unfair competition such as when the infringer discloses on the labels containing the mark that he manufactures the goods, thus preventing the public from being deceived that the goods originate from the trademark owner. In this case, no issue of confusion arises because the same manufactured products are sold; only the ownership of the trademarks is at issue.

Finally, with the established ruling that KUNNAN is the rightful owner of the trademarks of the goods that SUPERIOR asserts are being unfairly sold by KUNNAN under trademarks registered in SUPERIORs name, the latter is left with no effective right to make a claim. In other words, with the CAs final ruling in the Registration Cancellation Case, SUPERIORs case no longer presents a valid cause of action. For this reason, the unfair competition aspect of the SUPERIORs case likewise falls.

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- Divine Word High School Vs NLRCDokumen3 halamanDivine Word High School Vs NLRCVince LeidoBelum ada peringkat

- JOINT VERIFICATION & Certification Against Forum Shopping - Both Petitioners Are Spouses With Different ResidenceDokumen1 halamanJOINT VERIFICATION & Certification Against Forum Shopping - Both Petitioners Are Spouses With Different ResidenceelvinperiaBelum ada peringkat

- 1988 Labor Bar ExaminationDokumen18 halaman1988 Labor Bar ExaminationjerushabrainerdBelum ada peringkat

- Canlas vs. Napico Homeowners - DigestDokumen1 halamanCanlas vs. Napico Homeowners - DigestAntonio Paolo AlvarioBelum ada peringkat

- Case Digest 1-4Dokumen10 halamanCase Digest 1-4Patricia Ann Sarabia ArevaloBelum ada peringkat

- Alimpoos Vs CADokumen20 halamanAlimpoos Vs CAoliveBelum ada peringkat

- Aff. of Loss-Drivers LicenseDokumen2 halamanAff. of Loss-Drivers LicenseAmanda HernandezBelum ada peringkat

- Digest - Guy vs. CADokumen1 halamanDigest - Guy vs. CAIana VivienBelum ada peringkat

- Abbot Laboratories Vs NLRC, GR No. 76959Dokumen4 halamanAbbot Laboratories Vs NLRC, GR No. 76959Jha NizBelum ada peringkat

- Jacob vs. CA - 224 S 189Dokumen2 halamanJacob vs. CA - 224 S 189Zesyl Avigail FranciscoBelum ada peringkat

- 193 Sarmiento Vs CA, 394 SCRA 315 (2002)Dokumen1 halaman193 Sarmiento Vs CA, 394 SCRA 315 (2002)Alan GultiaBelum ada peringkat

- Onde Vs Civil Registrar Las PinasDokumen2 halamanOnde Vs Civil Registrar Las PinasPrhylleBelum ada peringkat

- 2022 Bar Exam Questions On Remedial Law 1Dokumen4 halaman2022 Bar Exam Questions On Remedial Law 1Sirc LabotBelum ada peringkat

- 006 Republic Vs Sandiganbayan 662 Scra 152Dokumen109 halaman006 Republic Vs Sandiganbayan 662 Scra 152Maria Jeminah TurarayBelum ada peringkat

- (G.R. No. 7123. August 17, 1912.) THE UNITED STATES, Plaintiff-Appellee, vs. ROSALINO RODRIGUEZ, Defendant-Appellant PDFDokumen2 halaman(G.R. No. 7123. August 17, 1912.) THE UNITED STATES, Plaintiff-Appellee, vs. ROSALINO RODRIGUEZ, Defendant-Appellant PDFZack SeiferBelum ada peringkat

- LNR Case DigestDokumen4 halamanLNR Case DigestMonica Bolado-AsuncionBelum ada peringkat

- Paramount Vs CaDokumen2 halamanParamount Vs CapatrickBelum ada peringkat

- Torts Case DigestsDokumen9 halamanTorts Case DigestsLea NajeraBelum ada peringkat

- 2.B Sample Bail Bond Undertaking For Judge Hugo Both Cash and SuretyDokumen2 halaman2.B Sample Bail Bond Undertaking For Judge Hugo Both Cash and SuretyBetty CampBelum ada peringkat

- Jaime Guinhawa v. PeopleDokumen2 halamanJaime Guinhawa v. PeopleMichelle BernardoBelum ada peringkat

- 14 CD PP Vs Miller OmandamDokumen2 halaman14 CD PP Vs Miller OmandamDorz B. SuraltaBelum ada peringkat

- $ttpre111e Qtourt: 3repul - Jlic Tbe L) BilippinesDokumen26 halaman$ttpre111e Qtourt: 3repul - Jlic Tbe L) BilippinesNicki BombezaBelum ada peringkat

- Domalsin v. Spouses ValencianoDokumen15 halamanDomalsin v. Spouses ValencianoAiyla AnonasBelum ada peringkat

- Legal Opinion EssayDokumen5 halamanLegal Opinion EssayAlly BernalesBelum ada peringkat

- Heirs of Amparo Del Rosario Vs SantosDokumen1 halamanHeirs of Amparo Del Rosario Vs SantosfinserglenBelum ada peringkat

- 38 - Suico v. NLRC, January 30, 2007Dokumen2 halaman38 - Suico v. NLRC, January 30, 2007Christine ValidoBelum ada peringkat

- Kilosbayan Vs MoratoDokumen10 halamanKilosbayan Vs MoratojazrethBelum ada peringkat

- Civil Case DigestDokumen9 halamanCivil Case DigestmarcialxBelum ada peringkat

- Bacarro vs. PinatacanDokumen9 halamanBacarro vs. PinatacanAndrea Nicole Paulino RiveraBelum ada peringkat

- Hofilena and Santos AdoptionDokumen2 halamanHofilena and Santos AdoptionBerniceAnneAseñas-ElmacoBelum ada peringkat

- S. D. MARTINEZ and His Wife, CARMEN ONG DE MARTINEZ, Plaintiffs-Appellees, v. WILLIAM VAN BUSKIRK, Defendant-AppellantDokumen3 halamanS. D. MARTINEZ and His Wife, CARMEN ONG DE MARTINEZ, Plaintiffs-Appellees, v. WILLIAM VAN BUSKIRK, Defendant-AppellantYanie FernandezBelum ada peringkat

- Medico Legal CertificateDokumen1 halamanMedico Legal CertificateMa Krissa Ellaine BundangBelum ada peringkat

- Romano Vs ParinasDokumen1 halamanRomano Vs ParinasInnah Agito-RamosBelum ada peringkat

- Quirong v. DBPDokumen2 halamanQuirong v. DBPAmalia TabingoBelum ada peringkat

- PHILIPPINE REFINING CO. Vs NG SAMDokumen1 halamanPHILIPPINE REFINING CO. Vs NG SAMchaBelum ada peringkat

- Trial Memorandum of The PetitionerDokumen11 halamanTrial Memorandum of The PetitionerAbegail Protacio GuardianBelum ada peringkat

- Maralit Case DigestDokumen1 halamanMaralit Case DigestKim Andaya-YapBelum ada peringkat

- 21 - Iglesias V Ombudsman PDFDokumen7 halaman21 - Iglesias V Ombudsman PDFMarion Yves MosonesBelum ada peringkat

- G.R. No. 138493 June 15, 2000 TEOFISTA BABIERA, Petitioner, vs. PRESENTACION B. CATOTAL, Respondent. FactsDokumen2 halamanG.R. No. 138493 June 15, 2000 TEOFISTA BABIERA, Petitioner, vs. PRESENTACION B. CATOTAL, Respondent. FactsKORINA NGALOYBelum ada peringkat

- $ Upreme Qi:Ourt: 3republic of TL) E FlfjilippinesDokumen19 halaman$ Upreme Qi:Ourt: 3republic of TL) E FlfjilippinesHuey CalabinesBelum ada peringkat

- Ocampo vs. Ocampo: G.R. No. 187879 July 5, 2010Dokumen9 halamanOcampo vs. Ocampo: G.R. No. 187879 July 5, 2010demBelum ada peringkat

- EstafaDokumen5 halamanEstafaMaeJoyLoyolaBorlagdatanBelum ada peringkat

- Bueno V Gloria (Issue 2)Dokumen6 halamanBueno V Gloria (Issue 2)Jan Re Espina CadeleñaBelum ada peringkat

- 008 - Chi Ming Choi v. CADokumen2 halaman008 - Chi Ming Choi v. CAIhna Alyssa Marie SantosBelum ada peringkat

- 37-Morabe v. BrownDokumen3 halaman37-Morabe v. BrownChiic-chiic SalamidaBelum ada peringkat

- Agrarian Law - Cases On TenancyDokumen15 halamanAgrarian Law - Cases On TenancyHoney Mambuay-BarambanganBelum ada peringkat

- 003 Mendez v. Sharia District Court (Art. 78)Dokumen3 halaman003 Mendez v. Sharia District Court (Art. 78)CareenBelum ada peringkat

- 2018 MOCK BAR-mercantileDokumen4 halaman2018 MOCK BAR-mercantileememBelum ada peringkat

- 78 Phil LJ1Dokumen26 halaman78 Phil LJ1IAN ANGELO BUTASLACBelum ada peringkat

- Baluran Vs NavarroDokumen1 halamanBaluran Vs NavarroKolin SopongcoBelum ada peringkat

- 019laconic RulesDokumen12 halaman019laconic RulesTendido TendoBelum ada peringkat

- Cerrano V ChuoDokumen2 halamanCerrano V ChuoKate MontenegroBelum ada peringkat

- G.R. No. 243891 - Legal InterestDokumen4 halamanG.R. No. 243891 - Legal InterestReginald PincaBelum ada peringkat

- People vs. DarilayDokumen16 halamanPeople vs. Darilayvince005Belum ada peringkat

- SALDANA v. NIAMATALIDokumen2 halamanSALDANA v. NIAMATALIDominique PobeBelum ada peringkat

- Syquia vs. AlmedaDokumen7 halamanSyquia vs. AlmedaiamnoelBelum ada peringkat

- Pe Vs Pe 5 Scra 200Dokumen2 halamanPe Vs Pe 5 Scra 200Lady Paul SyBelum ada peringkat

- Sunbeam Convenience Food Vs CADokumen15 halamanSunbeam Convenience Food Vs CALogia LegisBelum ada peringkat

- Servicewide vs. CADokumen2 halamanServicewide vs. CAFlor Ann CajayonBelum ada peringkat

- Ipl - Pro Line VS CaDokumen3 halamanIpl - Pro Line VS CaCookie CharmBelum ada peringkat

- TTX Human Trafficking With ANSWERS For DavaoDokumen7 halamanTTX Human Trafficking With ANSWERS For DavaoVee DammeBelum ada peringkat

- Notor vs. Martinez Case DigestDokumen1 halamanNotor vs. Martinez Case DigestConrado JimenezBelum ada peringkat

- City of Manila Vs Chinese CommunityDokumen1 halamanCity of Manila Vs Chinese CommunityEarl LarroderBelum ada peringkat

- Miske DocumentsDokumen14 halamanMiske DocumentsHNN100% (1)

- 1 Types of Life Insurance Plans & ULIPSDokumen40 halaman1 Types of Life Insurance Plans & ULIPSJaswanth Singh RajpurohitBelum ada peringkat

- IOPC Decision Letter 14 Dec 18Dokumen5 halamanIOPC Decision Letter 14 Dec 18MiscellaneousBelum ada peringkat

- Internal Orders / Requisitions - Oracle Order ManagementDokumen14 halamanInternal Orders / Requisitions - Oracle Order ManagementtsurendarBelum ada peringkat

- Ground Floor Plan: Office of The Provincial EngineerDokumen1 halamanGround Floor Plan: Office of The Provincial EngineerAbubakar SalikBelum ada peringkat

- Facts:: Matienzo vs. Abellera (162 SCRA 7)Dokumen1 halamanFacts:: Matienzo vs. Abellera (162 SCRA 7)Kenneth Ray AgustinBelum ada peringkat

- The Daily Tar Heel For Nov. 5, 2014Dokumen8 halamanThe Daily Tar Heel For Nov. 5, 2014The Daily Tar HeelBelum ada peringkat

- Mrunal Updates - Money - Banking - Mrunal PDFDokumen39 halamanMrunal Updates - Money - Banking - Mrunal PDFShivangi ChoudharyBelum ada peringkat

- Maint BriefingDokumen4 halamanMaint BriefingWellington RamosBelum ada peringkat

- NISM Series IX Merchant Banking Workbook February 2019 PDFDokumen211 halamanNISM Series IX Merchant Banking Workbook February 2019 PDFBiswajit SarmaBelum ada peringkat

- Business EthicsDokumen178 halamanBusiness EthicsPeter KiarieBelum ada peringkat

- FEE SCHEDULE 2017/2018: Cambridge IGCSE Curriculum Academic Year: August 2017 To July 2018Dokumen1 halamanFEE SCHEDULE 2017/2018: Cambridge IGCSE Curriculum Academic Year: August 2017 To July 2018anjanamenonBelum ada peringkat

- Agra SocLeg Bar Q A (2013-1987)Dokumen17 halamanAgra SocLeg Bar Q A (2013-1987)Hiroshi Carlos100% (1)

- Lancesoft Offer LetterDokumen5 halamanLancesoft Offer LetterYogendraBelum ada peringkat

- Model Test 15 - 20Dokumen206 halamanModel Test 15 - 20theabhishekdahalBelum ada peringkat

- The Micronesia Institute Twenty-Year ReportDokumen39 halamanThe Micronesia Institute Twenty-Year ReportherondelleBelum ada peringkat

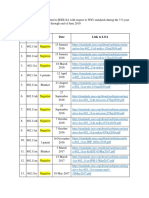

- WiFi LoAs Submitted 1-1-2016 To 6 - 30 - 2019Dokumen3 halamanWiFi LoAs Submitted 1-1-2016 To 6 - 30 - 2019abdBelum ada peringkat

- Jamii Cover: Type of PlansDokumen2 halamanJamii Cover: Type of PlansERICK ODIPOBelum ada peringkat

- K. A. Abbas v. Union of India - A Case StudyDokumen4 halamanK. A. Abbas v. Union of India - A Case StudyAditya pal100% (2)

- 09-01-13 Samaan V Zernik (SC087400) "Non Party" Bank of America Moldawsky Extortionist Notice of Non Opposition SDokumen14 halaman09-01-13 Samaan V Zernik (SC087400) "Non Party" Bank of America Moldawsky Extortionist Notice of Non Opposition SHuman Rights Alert - NGO (RA)Belum ada peringkat

- Article On Female Foeticide-Need To Change The MindsetDokumen4 halamanArticle On Female Foeticide-Need To Change The MindsetigdrBelum ada peringkat

- Performance Bank Guarantee FormatDokumen1 halamanPerformance Bank Guarantee FormatSRIHARI REDDIBelum ada peringkat

- Appendix 1. Helicopter Data: 1. INTRODUCTION. This Appendix Contains 2. VERIFICATION. The Published InformationDokumen20 halamanAppendix 1. Helicopter Data: 1. INTRODUCTION. This Appendix Contains 2. VERIFICATION. The Published Informationsamirsamira928Belum ada peringkat

- 1 Dealer AddressDokumen1 halaman1 Dealer AddressguneshwwarBelum ada peringkat

- Affidavit of SupportDokumen3 halamanAffidavit of Supportprozoam21Belum ada peringkat

- Yanmar 3TNV88XMS 3TNV88XMS2 4TNV88XMS 4TNV88XMS2 Engines: Engine Parts ManualDokumen52 halamanYanmar 3TNV88XMS 3TNV88XMS2 4TNV88XMS 4TNV88XMS2 Engines: Engine Parts Manualshajesh100% (1)

- Full Download Test Bank For Effective Police Supervision 8th Edition Larry S Miller Harry W More Michael C Braswell 2 PDF Full ChapterDokumen36 halamanFull Download Test Bank For Effective Police Supervision 8th Edition Larry S Miller Harry W More Michael C Braswell 2 PDF Full Chapteralterityfane.mah96z100% (12)