How de Gaulle Saved The French Republic 2

Diunggah oleh

AndrewJudul Asli

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

How de Gaulle Saved The French Republic 2

Diunggah oleh

AndrewHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

NEW SOLIDARITY

August 8, 1980

Page 6

How de Gaulle Saved the French Republic:

What Every American Needs to Know About Nationalism Part II by Garance Phau

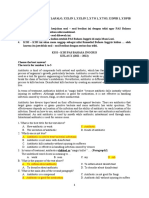

photo courtesy French Embassy

De Gaulle leads the chiefs of his Resistance movement down the Champs Elysees as Paris is liberated from the Nazis.

Forty years ago last month, General Charles de Gaulle called upon the French nation to take up arms against the Nazi occupants, and participate in a world wide effort to crush fascism. De Gaulle's call over the British Broadcasting Company radio, June 18, 1940, will be remembered as the launching of a Republican movement to rebuild Europe on the basis of the nation-state, and prepare the industrialized nations to undertake the development of the Third World. Yet, today, the French Gaullist Party, the Rassemblement Pour la Republic, is making a mockery of this commemoration. A prime example of the RPR's behavior was its demand that President Valery Giscard d'Estaing refrain from making an address to the nation on the topic of de Gaulle's accomplishments this past June 18, under pain of a major crisis in the ruling coalition made up of the RPR and the Giscardian UDF group. More outrageous still, a leading Gaullist called for a ''New Resistance," this time against the Soviets and Giscard's detente policy.

Thus, while the state could not commemorate de Gaulle because the President does carry the label "Gaullist," the self-proclaimed New Right could with impunity celebrate the memory of Marshall Petain's capitulation and entente with Hitler on June 17, 1940. The weekly Figaro Magazine ran polls showing that a majority of Frenchmen today look kindly on the Marshall and his role as head of the puppet Vichy government. These are not merely affronts to the memory of Charles de Gaulle. They are indications of how little his historic role is appreciated, at a time when it is crucial that the citizens of both Europe and the United States understand and mobilize behind the nation-building policies to which de Gaulle dedicated his life's work. In Part I of this series, we looked at de Gaulle's morality as a world leader and reviewed the national and family tradition he drew upon, reaching back to the French Ecole Polytechnique. We laid out his plan to reconquer the French Empire in Africa, as the precondition to implementing a war-winning strategy for the Allies on the European continent. In Part II, we will see the realization of this strategy, whose success was based on de Gaulle's unshakable commitment to the development of the Third World. To look at World War II through the actions of General de Gaulle is the best way to dispel the myth of Winston Churchill as the courageous antifascist warrior, and provide an accurate historical account of how the war was won. De Gaulle, a humanist republican and one of the greatest military strategists of the century, provided the direction and leadership to Allies that allowed them to implement a war-winning strategy in the face of Churchill's treacherous, Utopian doctrine. De Gaulle's relations with Churchill demonstrate that Great Britain's ruling strata were nothing but the unrepentant traitors against the Allied war effort and sub-rosa supporters of the Hitler onslaught recent historical exposes have proven them to be. Churchill's role in the infamous Dakar massacre of Free French troops and its fleet in the summer of 1941, is but one of the most bloody of the stories of his treachery. After his brilliant capture of French Equatorial Africa, and the establishment of a secure base of operations on the continent, de Gaulle laid plans for the capture of Dakar, a strategic port on the Atlantic Ocean. The capital of Senegal, as well as the leading city of French West Africa, Dakar, in the

hands of the Free French could serve as an open door to North Africa, and secure Allied control of the entire continent. Since Dakar's Governor Boisson was a committed Vichyite and the town itself was fortified, de Gaulle decided against the frontal attack tactic that had won his first victory in Brazzaville. He planned to land a small group of Free French fighters in Conakry, from there to walk to Dakar, rallying loyal French colonialists along the way. But to succeed, the strategy needed a British ship or two to divert Boisson's attention and leave his rear flank open. De Gaulle requested British naval support from Winston Churchill. Churchill refused. Instead, after consultation with British intelligence, he put forward a counterproposal: that Dakar be taken with the deployment of a vast Armada of British and Free French ships for a frontal attack from the Atlantic. Churchill also made clear that his proposal would prevail. The armada would be deployed with or without de Gaulle's approval. The General was forced to concede. It was on September 27, 1941 while he was well on his way to Dakar as the commander of the Free French Navy, that de Gaulle learned that a large squadron of Vichy war ships was steaming toward Dakar. The squadron had successfully passed through the Straits of Gibraltar at the mouth of the Mediterranean without any opposition from the British, who were in control of the straits. All sources in the public domain report that the British officers in charge of the Gibraltar bottleneck, as well as the king's Admiralty itself, were informed of the deployment of the Vichy ships by the British ambassador to Madrid, among others. They took no action, and let the Vichy ships pass. On September 28, Vichy and Free French naval forces met in the waters off Dakar, and a bloody battle ensued. Free French losses were high, and military gains were nil, Dakar having armed itself to the teeth in anticipation of the attack. The only concession that de Gaulle wrested from the British came from Admiral Cunningham, who barred the road from Dakar to Brazzaville, preventing the loss of territory gained by the Free French earlier in de Gaulle's Africa campaign. The failure of the Dakar expedition was the occasion for an international press smear campaign against de Gaulle, who was smashed as an adventurer

who had told the British that the "town would fall into his lap with a mere show of strength" (New York Times, September 28). Churchill and his associates glossed over British responsibility in the affair to pretend that the "leaky" Free French organization was responsible for the fiasco because they allegedly passed the word onto Vichy, that argument was especially used to impress upon the Americans that indeed de Gaulle should be kept out of strategic planning lest Allied plans made their way to Berlin via Vichy. British confidence ran so high that after Dakar London openly resumed its contacts with the Vichy government and lifted embargoes against the Vichy controlled colonies. That Churchill was able to deprive the Allied military of the collaboration of de Gaulle in its strategic planning was no small victory for London. But Churchill and his controllers wished to be rid of the general altogether. Their favored weapon was the Vichy apparatus, its police, and its armed forces, through which various assassination plots were run. Vichy was encouraged to carry out a popular anti-Gaullist mobilization, which was characterized by the initiation oath of the French Legion (the Vichy branch of the Nazi S.A.): "I swear to fight against democracy, Gaullist dissidence, and Jewish leprosy." Even Marshall Petain was called upon at one point to play a direct role in an assassination plot against de Gaulle. Petain reports in his memoirs that he refused: A messenger came to see me from London for the specific purpose of relaying through one of my ministers the following remarks made by one of the most prominent people on England: "De Gaulle is a nuisance to us. He thinks he is Joan of Arc. Well, we are going to burn him and we shan't need a stake as we did in 1431. We only have to tell the Vichy government the day and time of his next flight to the Middle East and give them the flight schedule. (Petain replied): "I have not received your communication. I refuse to do anything dishonorable. Let the British cope with de Gaulle on their own. Russia's Entry into the War Nowhere was the fundamental antagonism between de Gaulle and Churchill made clearer than in their respective responses to the entry of the Soviet Union into World War II in June of 1941, Churchill hailed privately the

breakup of the Hitler-Stalin pact as the opening for the realization of the dreams of the British Empire. He, and the British military strategists saw the moment at hand when Hitler would destroy Russia, finishing off the last standing nation-state on the continent. They envisioned a British rule over a totally broken Europe, with its industry in ruins that had been reduced to a feudal-like collection of petty kingdoms. De Gaulle, conversely, saw Russia's entry into the war as a branch point which could shift developments decisively toward an Allied victory. Although de Gaulle never considered himself a "friend of communism," he saw in the U.S.S.R. a great Russia nation, which had continued through decades of struggle for development and industrialization. From this perspective, de Gaulle considered the Soviet Union a proper and powerful ally of other European nation-states. In his memoirs, de Gaulle notes that although Stalin and Lenin characterized their programs as Bolshevik, the essence of their program was the development of a stronger Russian nation, a goal of other great humanists, such as Count Sergei Witte. Against the military and historical tradition of the Russian nation, communism was a mere ephemeral form. De Gaulle has a remarkably insightful perception of Stalin and beyond him of the nature of Soviet Union's government and policy generally. In his memoirs, referring to his trip to the U.S.S.R. as President of the Republic in 1945 to seal a Franco-Soviet alliance, de Gaulle poetically says of Stalin that he had violently made his way to the top: But once there, alone face to face with Russia, Stalin saw her as mysterious, stronger and more durable than all the doctrines and all the regimes. He loved her in his own way. She herself accepted him as a Czar for the time of a terrible period and withstood Bolshevism to use it as an instrument. De Gaulle was saying something that the United States elite fails to understand: the Soviet Union may pledge allegiance to "MarxismLeninism," its leadership may even think they are acting on those " MarxistLeninist" principles, but the truth is that Soviet leaders are at bottom true nationalists, and as such will tend toward Republican policy. That was the basis for de Gaulle's launching of detente in the 1960s.

When the Soviets entered the war, de Gaulle immediately extended his whole-hearted support to the Red Army over the BBC airwaves. He negotiated with the Soviets to arrange for the deployment of the Free French regiment to the Eastern front to fight against the Nazi invaders of the U.S.S.R. These became famous as the "Normandy Niemens Regiment," and remained on the Eastern front until the end of the war in Europe. The Second Front The Eastern war now posed the question: could and should the Allies open a second European front against the Nazis, while the German army occupied itself in Russia? Stalin, de Gaulle, and U.S. Chief of Staff General George Marshall were in agreement that the opening of a second front was urgent, and should move into the planning stages immediately.

This was in the autumn of 1941. Allied action was planned for mid-1942. Yet, the opening of the second front with the invasion of Normandy did not take place until 1944. In the interim, millions died in the Nazi concentration camps, and on the battle fields. What was the reason for this delay? Largely, it was the result of British dominance over Allied policy-making. A 1941 paper by Churchill shows what British policy was. Written under the headline, "Proposed Plan and Sequence of the War," Churchill argued against the mass deployment of Allied troops into the heart of Europe. He also suggests the diversion of the United States away from plans for the opening of a second front by launching "secondary overseas operations." Churchill's document is a crystal clear exposition of the British cabinet warfare outlook, left over from the 19th century, which held sway over the Allied military command for much of the war. Like their latter-day counterparts, the British military strategists of World War II did not believe in warfighting in depth. They, and Churchill preferred "limited" or "proxy" wars and staunchly opposed the creation of a large Allied land army on the continent. From early 1941, until the Allied landing in Normandy in June 1944, Churchill left no stone unturned in his effort to prevent a meeting of the minds among Roosevelt, the U.S. Chief of Staff Marshall, who supported de Gaulle, and de Gaulle. Roosevelt was cordoned off from de Gaulle with the help of such British agents in Washington, D.C. as Jean Monnet. During World War II, as today, the degree of British control over the White House could be calculated by the health of Franco-American relations. With the British in sway due to the success of Monnet and Churchill, relations with de Gaulle were frozen. But in the early part of 1942, and during other times when General Marshall and his aides could temporarily win Roosevelt away from Churchill's follies, America seriously considered de Gaulle's proposals for a second front. Conversations during mid May of 1942 between U.S. Ambassador Winant and de Gaulle indicate the degree to which U.S. cooperation with the Free French for the opening of the second front had proceeded. One of the discussions, a discussion of May 21, was recorded by de Gaulle in his memoirs: de Gaulle: This front must be opened as soon as possible.

Winant: Can you suggest the best moment for this operation? de Gaulle: As soon as the Germans are fully occupied in Russia. . . The Germans will not be fully engaged there before July. It is thus from the month of August that a landing in France should be envisaged. . . Winant: What in your opinion would be the best method to employ? de Gaulle: To land a large task force on an extended front at the very beginning would be a very good thing. The resistance those units would encounter would tell the Allied command of the most favorable spot to land large forces, at the same time leaving the Germans in the dark. Then, and with the least possible delay, the real landing should take place, this second phase would require air support of very considerable strength. The landing zone should be between Cotentin and Cap Grisnez. . . Winant: Do you think the war could be won this year? de Gaulle: That depends on the strength you are prepared to use. The effort you could make this year is obviously not the maximum. This could only be attained in a year or two. But from now on I am convinced that if the United Nations, having sufficient forces, succeeds in the landing the war could end before the end of the year. The Algiers Quagmire But by July 1942, a mere two months after the Winant-de Gaulle discussions, the British had succeeded in again reversing Roosevelt on the question of a second front. With Roosevelt in his pocket, Churchill forced General Marshall to endorse an Allied landing in Algiers in place of the second front operation on the continent. The Algiers deployment proved to be one of the most costly and useless operations of the entire war. Roosevelt was duped into agreement with the North Africa move largely due to his eagerness for aggressive military action during 1942, and his frustration over British sabotage of Operation Sledgehammer, an early Normandy invasion plan. The British also used the lying argument that Allied possession of Algiers would increase shipping of military materiel

throughout the Mediterranean, and would not disturb plans for a crosschannel invasion of Europe which would be scheduled for early 1943. Newly appointed Commander Eisenhower was put in charge of organizing the Algiers operation, which received the codename "Operation Torch." Privately, Eisenhower confided his fears that Operation Torch would provoke both Spain and Vichy France into the war against the Allies. From the Pacific, the great American General MacArthur fulminated against "this absolutely useless" operation which would imperil support for his tactical commitments. U.S. General Marshall asserted that the Algiers landing would suck up men and equipment necessary for a near-future Normandy landing. But his protests were overruled and Churchill's plan was put into operation. The Allies landed in North Africa on November 7, 1942. Before one week of fighting was over, the consequences of Operation Torch proved as disastrous as the American generals had predicted. The deployment brought neutral territory into the war, and generally to the advantage of the Axis. First, the Axis moved swiftly into Tunisia; there they stayed, to be dislodged only after a year of costly fighting. Back on the continent, Germany was left free from pressure on its western flank to continue its attack against the Soviet Union. Shortly after the Allies landed in North Africa, Germany redeployed 27 regiments from the West onto the Eastern front against the Soviets. De Gaulle and the Free French watched as the consequences of Operation Torch were felt in France. Three months after the landing, Nazi tanks rolled over southern France, ousting the Vichy puppets and continuing on their way to Toulon where the Vichy fleet was disbanded, and then to Paris. While Churchill telephoned de Gaulle to extend his "condolences" over the destruction of the French fleet, there began the most horrible period of suffering for the French people in this century. Nazi forced labor was instituted nationwide. Tens of thousands were conscripted every month for deportation into Germany, where they were worked to death. The leaders of de Gaulle's resistance movement, including Jean Moulin and General Delestain, the head of the Secret Army, were hunted down and murdered, in many cases after having been fingered by British agents.

The whole story told, the Allies won nothing in North Africa. Behind the scenes the deceitful Churchill was working to make sure that this was the case. De Gaulle was forcefully excluded from all planning for Operation Torch. But Churchill and British intelligence's Office of Strategic Services made full disclosure of Allied plans to Vichy Chief of Staff Weygand. In a tragic replay of the Dakar massacre, the informed Vichy forces welcomed the Allies to Algiers not with open armsas Churchill had predicted to Rooseveltbut with bullets. Within two days, the Nazi-collaborating Vichyites had the upper hand, and the Allies conceded to a ceasefire. The ceasefire was followed by one of the most disgusting episodes of American diplomacy disgracing itself under British influence. Admiral Darlan, the number two man of German puppet Marshall Petain, was made the governor of the whole of French North Africa. The U.S. Army was used to help enforce the anti-Semitic, forced labor laws that were the hallmarks of Vichy rule. Several weeks after this compromise was struck, Darlan was murdered, and the Anglo-American team who had arranged his governorship took the opportunity of his death to bring in one General Giraud. This handpicked governor they hoped could appeal to the population and more efficiently maintain control than the hated Darlan. De Gaulle maneuvered masterfully to win North Africa out from under Giraud and his British controllers. De Gaulle did not attack Giraud personally, instead proposing that Giraud become part of the Free French movement, and take direction from de Gaulle, the sole legitimate representative of France. This outraged Churchill and the British, who repeatedly demanded that de Gaulle subordinate himself to the Alliedbacked Giraud in policy-making for the North African theater. The general refused. Throughout this period de Gaulle did enjoy the support of one American, General Douglas MacArthur, who did not hesitate to express his outrage at the Roosevelt administration's treatment of the Free French. One April 1, 1943, MacArthur met with de Gaulle's emissary Laporte in the Pacific, sending this message back to de Gaulle through Laporte: Laporte, as an American and as a soldier, I am ashamed of the way in which certain people have treated your leader General de Gaulle. The villainy behind the sad affair in North Africa

will take a long time to efface. I am far away from it all but I must say to you that I personally disapprove of the attitude of Roosevelt and Churchill to General de Gaulle. Please tell him of my affection and my admiration for his attitude to current events. Insist that I feel he must, at all costs, pursue his ideal of a Republican France, and that he must not give in to Giraud, who first of all signed a compromise with Vichy, then put himself under American orders. The only thing that counts is the ideal which was the origin of Free France. . . Tell him that I wish him success in his opposition to any agreement which would put him in a secondary position. He is, as I am myself upheld by public opinion, not only in French territory but also in the United States and Great Britain. . . I believe that your country, once purged of its degraded groups, will rise to be more glorious and powerful than ever. . . This can only be achieved under the leadership of the man who, in the terrible days of defeat, kept your flag flying. Turning of the Tide In May of 1943, the Allies invited de Gaulle to a conference in Casablanca. There, OSS agent Murphy, the man who had arranged the Darlan governorship of North Africa, insolently bragged to the French leader, "There isn't 10 percent of North Africa which is Gaullist." Five months later, Murphy was proven wrong by developments in North Africa which no doubt caused Winston Churchill more than one fit of apoplexy. The persistent organizing of de Gaulle around his program tor the revival of a French nation that could once again hold its place as a leader among the sovereign republics of the world spread the Free French movement across North Africa. Giraud's soldiers began to defect in order to join with de Gaulle's forces. Soon support for de Gaulle was so widespread that when the general became head of the French government in exile, Giraud was forced to concede his leadership and took the subordinate position of head of the French armed forces. Touring North Africa in summer 1943, de Gaulle brought out crowds of hundreds of thousands in every major town. Hundreds of thousands turned out at a massive demonstration in Algiers to see and hear de Gaulle. On July 14 he told the crowd, as recorded in his memoirs:

Daily life, people's consciousness was again focused on the nation. . . Since Vichy could not fool anyone, the people, out of enthusiasm, true allegiance, or sheer opportunism, went naturally to de Gaulle. . . In North Africa, this process had been slowed by the ethnic and political structure of the population, by the attitude of the authorities, and by the pressures of the Allies. But this process became irresistible. A flood of support consecrated our effort, the deep-seated legitimacy of the French nation . . . which has always been with France even in the depths of her worst trials, whatever the legal formulas of the moment might be. Throughout the summer, de Gaulle toured Morocco, Tunisia, and Algeria, bringing out masses wherever he stopped. The Allies, let alone Churchill himself, could not hope to contain this upsurge of support. Soldiers from Giraud's army continued to defect to join the Free French flag, and soon a trickle had become a stream. The exodus took place in every port where ships from the Giraud-commanded merchant marine docked. At one point, the Washington, D.C. administration was so distraught over the number of marines leaving to join the Free French from U.S. ports they sought to stem the tide by locking up French marines as "deserters." This tactic was a shortlived failure. From June to November 1943, de Gaulle consolidated his government in exile, preparing for the rebuilding of the French republic and the final, decisive battles of the war. For de Gaulle, the most important battle was won when he successfully led the Allied command to adopt final plans for the successful 1944 Normandy invasion of France and the opening of the second front. With the Russian defeat of the Nazi onslaught on the eastern front, de Gaulle's conviction that republicanism would win out in the second great world war of the century was given new life. As the head of a vast French Empire, secured during the political organizing of the war years, de Gaulle's postwar tasks came more clearly into focus. For the joint task of reconstructing the French nation, and preparing France to lead a full-scale development thrust into the Third World, de Gaulle appointed a General Secretariat for the French government. His first appointees to the new government were Louis Joxe and Raymond Offroy. (to be continued)

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- John Quincy Adams and PopulismDokumen16 halamanJohn Quincy Adams and PopulismAndrewBelum ada peringkat

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- John Burnip On Yordan YovkovDokumen6 halamanJohn Burnip On Yordan YovkovAndrewBelum ada peringkat

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5794)

- Mozart As A Great 'American' ComposerDokumen5 halamanMozart As A Great 'American' ComposerAndrewBelum ada peringkat

- Geometrical Properties of Cusa's Infinite CircleDokumen12 halamanGeometrical Properties of Cusa's Infinite CircleAndrewBelum ada peringkat

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (400)

- British Terrorism: The Southern ConfederacyDokumen11 halamanBritish Terrorism: The Southern ConfederacyAndrewBelum ada peringkat

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (588)

- The Shape of Things To ComeDokumen20 halamanThe Shape of Things To ComeAndrew100% (1)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- Modern Industrial Corporation Created by The Nation StateDokumen12 halamanModern Industrial Corporation Created by The Nation StateAndrewBelum ada peringkat

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- Bach's Campaign For An Absolute System of Musical TuningDokumen19 halamanBach's Campaign For An Absolute System of Musical TuningAndrew100% (1)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (895)

- Leibniz - Agape Embodies Natural LawDokumen9 halamanLeibniz - Agape Embodies Natural LawAndrewBelum ada peringkat

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- Life and Death of Sir Thomas More 1Dokumen21 halamanLife and Death of Sir Thomas More 1AndrewBelum ada peringkat

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- Century-Long Fight For Ibero-American IntegrationDokumen19 halamanCentury-Long Fight For Ibero-American IntegrationAndrewBelum ada peringkat

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- Fifty Years' Subversion of Scientific AgricultureDokumen5 halamanFifty Years' Subversion of Scientific AgricultureAndrewBelum ada peringkat

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (266)

- Yugoslavia - Battleground of The South Slavs 2Dokumen22 halamanYugoslavia - Battleground of The South Slavs 2Andrew100% (1)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (74)

- Madame Blavatsky The Making of A SatanistDokumen12 halamanMadame Blavatsky The Making of A SatanistAndrewBelum ada peringkat

- 09-10 Arts and Humanities CoursesDokumen132 halaman09-10 Arts and Humanities CoursesAlain JuperBelum ada peringkat

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- Suchitra - PressDokumen13 halamanSuchitra - PressSagnik BiswasBelum ada peringkat

- FMS P-038 German Radio IntelligenceDokumen294 halamanFMS P-038 German Radio Intelligencepaspartoo100% (1)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- Product Catalogue 2008Dokumen17 halamanProduct Catalogue 2008plsdBelum ada peringkat

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (345)

- Busking in Victoria - Memories (Dave Harris)Dokumen7 halamanBusking in Victoria - Memories (Dave Harris)scribdaccountBelum ada peringkat

- Penguin Readers - Three Great Plays of Shakespeare - Level 4Dokumen39 halamanPenguin Readers - Three Great Plays of Shakespeare - Level 4Σωτήρης Μαλικέντζος100% (3)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2259)

- James Nederlander Transcripts. Michael Jackson Exe. Branca V IRSDokumen20 halamanJames Nederlander Transcripts. Michael Jackson Exe. Branca V IRSTeamMichaelBelum ada peringkat

- Final Test S&LDokumen6 halamanFinal Test S&LSara Tatiana López RincónBelum ada peringkat

- The Nature of TragedyDokumen3 halamanThe Nature of TragedyCarla100% (1)

- KISI - KISI PAS Kelas 10 (Semester Genap) 2022-1Dokumen5 halamanKISI - KISI PAS Kelas 10 (Semester Genap) 2022-1Retalia Indah sariBelum ada peringkat

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- Dream 16 Casting InformationDokumen5 halamanDream 16 Casting Informationapi-258194502Belum ada peringkat

- Reviewer Topic 2 Sydney Opera HouseDokumen2 halamanReviewer Topic 2 Sydney Opera HousevialnetroscapeBelum ada peringkat

- Etienne-Decroux. Thomas - Leabhart PDFDokumen82 halamanEtienne-Decroux. Thomas - Leabhart PDFSamay AbadieBelum ada peringkat

- Poetry: "Poetry Is Thoughts That Breathe, and Words That Burn."Dokumen18 halamanPoetry: "Poetry Is Thoughts That Breathe, and Words That Burn."Estepanie GopetBelum ada peringkat

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (121)

- Mozart Biography and NotesDokumen5 halamanMozart Biography and NotesBob BaoBabBelum ada peringkat

- ScriptsDokumen22 halamanScriptsHazman GhazaliBelum ada peringkat

- 018-The School For ScandalDokumen2 halaman018-The School For ScandalMisajBelum ada peringkat

- Revolution of Hope: Independent Films Are Young, Free and Radical by Katinka Van HeerenDokumen4 halamanRevolution of Hope: Independent Films Are Young, Free and Radical by Katinka Van HeerenRagam Networks100% (1)

- Reaction PaperDokumen2 halamanReaction PaperAngel Villamor100% (1)

- Anti HumorDokumen2 halamanAnti HumorMerimba Bara SingaBelum ada peringkat

- Inventing The Opera HouseDokumen276 halamanInventing The Opera HouseIvánBelum ada peringkat

- Acting " ": WorkshopDokumen8 halamanActing " ": WorkshopGilihac EgrojBelum ada peringkat

- Bengal Tiger at The Baghdad ZooDokumen35 halamanBengal Tiger at The Baghdad ZooJosh Warner100% (18)

- Hindustan TimesDokumen46 halamanHindustan TimesRavindra Varma PvsBelum ada peringkat

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)

- Voice-Over Voice Actor: Chapter 4 Before You Get To The Audition (Includes Warm-Up)Dokumen24 halamanVoice-Over Voice Actor: Chapter 4 Before You Get To The Audition (Includes Warm-Up)Tara Platt100% (3)

- Iturriaga - Pregón y Danza Works For Piano - Watermark Excerpt PDFDokumen13 halamanIturriaga - Pregón y Danza Works For Piano - Watermark Excerpt PDFRokiBelum ada peringkat

- Antic DispositionDokumen30 halamanAntic DispositionSaeed jafariBelum ada peringkat

- British Academy of Performing ArtsDokumen2 halamanBritish Academy of Performing Artsjturner773Belum ada peringkat

- Carl OrffDokumen5 halamanCarl OrffMohd Harqib HarisBelum ada peringkat

- New York Wing CommandersDokumen2 halamanNew York Wing CommandersCAP History LibraryBelum ada peringkat

- Stalin's Daughter: The Extraordinary and Tumultuous Life of Svetlana AlliluyevaDari EverandStalin's Daughter: The Extraordinary and Tumultuous Life of Svetlana AlliluyevaBelum ada peringkat