Thomas Molnar, Crisis

Diunggah oleh

MaDzik MaDzikowskaDeskripsi Asli:

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Thomas Molnar, Crisis

Diunggah oleh

MaDzik MaDzikowskaHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Crisis

Thomas Molnar

THETERM IN THE title is used with an increasing frequency, and we risk getting accustomed to it, living with it. This is inevitable as our public, or rather civilizational mood becomes similar to that of all decadent ages. And the similarity does not stop there: like the contemporaries of o t h e r ends-of-times (see Romano Guardinis title some thirty years ago), we too deny what is around us and what we may expect. Jacques Bainville wrote that the majority o men never have the imagf ination to conceive other roads than the familiarly trod one; crises confront us head-on, bringing tragedy but no awareness. Nonetheless, the elite somehow feel that our world is collapsing, and they respond to this perspective in a variety of ways. My purpose here is not to argue whether the collapse is near or far or what forms it might take; it is to examine these responses, at least some of them. A further restriction: not the response of the official elite: government, world bodies, the leading media, and the bureaucracies-which generally affirm that the prospects are encouraging, the GNP is rising, more raw material will be found (on the ocean bed and in space) for greater material progress, and more educational television programs will be broadcast for the culturization of all. The elites responses I plan to review here are derived from serious minds-writers, thinkers, scholars, prophets, psychologists, priests. The crisis, as these men see it, affects the two oldest public institutions, Church and State. Contrary to constitutional provisos and the theories of modern politologues, the two cannot be separated; their cleavage marks the first step in the crisis. Jean Hani, in La Royautk sacrke (Paris,

1984), argues that natural inequality requires a hierarchical structure through which inequality is socially integrated. Otherwise, disorder ensues, the material which holds society together becomes porous, brittle, and the body politic falls apart. In this analysis, the king or emperor (in Egypt, Persia, Judea, China, Japan, medieval states, etc.) holds the edifice together as representative of the divinity, yet subject to some form of popular investiture, less by vote than by acclamation. Leaving the institution of kingship aside, young sociologist Jean-Pierre Dupuy from the Ecole Polytechnique presents (in Ordres et desordres, Paris, 1982) a complementary thesis. Modern societys crisis should be explained by the fact that it recognizes no reference-system beyond and above itself, so that the citizen acknowledges no transcendental source of authority or ordering principle. Everybody being equal like gas molecules in a container, the constant agitation appears to be the only law, motivating each molecule to rise to the top. This is what classical authors used to call anarchy, the end-product of democracys inherent logic. To a question at a recent lecture at the Sorbonne (on legitimacy), I suggested that the two just-mentioned analyses are borne out by the respective state of some continental nations over against the United States. The former (France is the paradigm) had undergone a radical revolution, a symbolic decapitation of the rule of the sacred reference, affecting both State and Church. The popular sovereignty that followed conforms indeed to Dupuys thesis since the citizens have doubt about the validity of their own sovereignty, when in practice their

Modern Age

215

elected representatives behave in the manner of an oligarchic class, involved full-time with their own interests (accumulation o power, re-election, enrichment), f and only part-time with the interests of those whom they represent. They put o n a mask (the persona of Hellenic tragedy) which allows them to play two roles. In opposition to nations which have killed their God and king, I then pursued: the United States has not gone through this inverted metanoia, has not separated itself from the ancestral (English) constitution, from the Bible, from a superior referencenetwork. Practically the entire citizenry, in spite of the anarchy of American civil society, holds on to the belief of standing under God and a system of government not unlike the early Puritans town meeting, thus a semi-religious institution. Perhaps half o Americas population is by f now atheistic and immoral, cynical, and disaffected; yet the public discourse has not separated itself from its origin in Gods will. With such considerations, however, we do not close the debate; we merely gain a vantage point from which the crisis makes sense. For situations are not static, they follow a trend, as is obvious when we f observe the alienation o huge blocks of people, also in the United States, from national ideals, morality, legal system, religion, institutions-and even from the very concept of popular sovereignty. After all, an alienation whose habitual form is now increasingly violent-from strikes to terrorism to child-abuse to legalized abortion-cannot be a simple problem of statistics, better playgrounds-or further psycho-sociological research. Disaffection seems to be built into the routinized life in mass-industrial societies. Remove the routine and the prosperity that sustains it, and the bottom of the abyss could not even be perceived. Hence, other diagnosticians of the crisis descend beyond the social and political platform of observation. The one immediately below, the deeper root of the crisis, is our psychological vision. At rnidcentury, we still called it depth-psychol-

ogy, theorizing that the general malaise is engendered by the clash o the individual f libido as its drives are thwarted by the real world. Freuds illusion (the exact opposite of what he suggested in The Future of an Illusion, namely religion) was that man could be emancipated from the stormy impulses of his psyche (first step), and (second step) that a world of psychoanalyzed individuals would create a state of affairs without conflict, a liberated humanity. With Jung and his followers the scene shifted from the individuals mini-drama to the collective historical dimension, to the archetypes from which we borrow our psychic structure. Religion, for Freud, was a vast network of illusions; for Jung, the denial of religion and of strata yet deeper was the real source o psychic phenomena f observed in the modern patient and generally in modern man. The crisis received thus a new face: it became civilizational, and more, eventually cyclical, perhaps cosmic. At any rate, an entirely new depth became vaguely visible in the psyche, in behavior, in mans historical existence, a depth probed by the structuralists, the existentialists, the hermeneutes, the mythologues. Interestingly, this new depth has something in common with the latest in mathematics and nuclear physics: both areas, the psychological and the scientific, have given up their foundation in common sense, in rational judgment. Mathematics has become a game theory, its roots no longer in the observable world but in its own arbitrarily multiplied conventional signs; psychology, with its extension toward anthropology and culture-analysis, has left the field of the verifiably conscious, even of the conventional subconscious, surrendering to the collective myth that nobody is able to ascertain via introspection. Levi-Strauss writes: Things happen as if society and culture emerged in response to the problem of death: society exists in order to prevent the animals (mans) consciousness of death, and culture arises as mans reaction to the fact that he exists (Paroles dond e s , Sorbonne lectures, 1984). After this, how can one regard existence and culture

216

Summer/Fall198 7

as anything but alienating? Others could be quoted, the sum o f whose work seems to be the outright debunking of man, consciousness, the content of this consciousness, of meaning, of aspirations, of civilization. Returning for a moment to Jean Hani and J.-P. Dupuy, it becomes evident that on such a theoretical infrastructure that Levi-Strauss and others present, no sacred realm, not even a well-ordered political body can be erected. But let us tread the Jungian path. Jungs disciple James Hillman tries to rehabilitate the psyche as others, e.g., Saussure and Benjamin Whorf, have rehabilitated language. What do these endeavors aim at? They aim at the demonstration that the psyche (or language) is an independent phenomenon, having its own structure, without a substratum in consciousness and intelligence. Language, for Whorf, is a network of signs, so free from servitude to mans perceptions and the inner life which it is supposed to express according to old theories, that, in fact, it dictates through its own rules how we conceive things and make statements about them. In short, it is a selfcontained system, a structure, which determines our thoughts and conduct. As Professor Jean Brun writes (Lhornrne et le langage, Paris, 1985), the divine and the human dimensions of language disappear in this theory, the modulation of words as they express poetry, mystery, love, and awe. Similarly the psyche as it is interpreted by Hillman: it exists as bundles of pulsions, each with its own volition toward uninhibited self-expression. Pulsions and selfexpressions were what the pagans (always the Greeks, who were good pagans) called gods, thereby deifying instinctual life and emancipating it from under the publics and the authorities moral tutelage. Christianity decisively interfered with the unobstructed life of pulsions; it turned them generally over to the devils domain. Pulsions, in Hillmans, Foucaults and others interpretation became sins, their psychic energy repressed. Two thousand years o Christianity has mutilated them, f

and medical practice diagnosed them as sickness. Only a restored pagan view, beyond good and evil, will be able to erase psychic illnesses,by looking at the symptoms in a positive light. WE HAVE THUS THE modern psychological view of man, linking up with, and to a large extent causing, the political malaise, what we called the first manifest face of the crisis. How are we to interpret their combined significance? On the level of the community, the crisis can be said to be societys (nations, familys) detachment from transcendence, its personifications and symbols. It is not impossible that at the present time, without our being aware of it, a new link is forged between the community and its providential agent. One question, which I am not trying to examine here, is precisely whether the de-sacralized, self-ceferential society is viable, whether we are entering a historical era of spiritually selfcontained societies. For the time being, this is exactly what we would have to call totalitarian societies (described by A. Zinoviev in a frighteningly prosaic mode), omitting now the obligatory reference to Hitler and Stalin as if the phenomenon were not taking place elsewhere too, closer to home. As said before, it is not impossible that communities may live in a state of exile from God; the crisis may become institutionalized. However, we approach a more complete elucidation of the crisis if we consider the level on which modern psychology operate^.^ Societys separation from God (a historic first, reserved for our age) has its parallel in the individual psyches separation from moral judgment. Society, so say our authors, cannot function without transcendence built into its structure; the soul is similarly stunted without a guiding education in virtue. Jungs, Hillmans, Foucaults and Levi-Strausss presupposition is that (a) what we mean by f virtue, morality, the distinction o good and evil is conditioned by the Christian view o God and man, and that @) it is a f superimposed, arbitrary blockage of other

Modern Age

21 7

views. The Christian view was vigorous enough to build a civilization on this presupposition, but now, in Hillmans words, it is no longer an adequate civilizational vehicle. In sum, it now blocks the psyches energy: it causes symptoms of psychic disorder and sickness. We must turn to the pre- or post-Christian understanding of human behavior and thus free the psyche from its Christian moral bonds. Thus we reach the third component of the crisis, the plane of religion. The contemporary elite (philosophers, students of mysticism and myth, anthropologists, etc.) may be labelled gnostics, but only if we do not mean by the term any particular sect of the first centuries, e.g., the Valentinians, the principal movement, but adopt Gilbert Durands overall definitions: Gnosis is the integrated and redeeming knowledge. In this sense, we do not have to meticulously examine the eastern Mediterranean area in the second and third centuries, but detect the human penchant for salvation through a secret doctrine in which one must be initiated in order to achieve effectiveness. This doctrine (see details further on) is always popular in time of ~ r i s i sbecause ,~ it presents to erudite and probing minds the second-best option after a discredited Christian theology and dogmatics with which many people refuse to be associated or to which they claim to have found more persuasive alternatives. Thus, to return to our time, a kind of new religion has arisen, which is that of the philosophers, not of Jesus Christ, as Pascal put it with great precision three centuries ago. It is an intellectual magisterium, equidistant from the earlier decades crude disbelief and from traditional monotheism. It finds expression in many places, in the study of esotericism, of oriental religions, in Eliades work, in Islamology, and also in small groups of Western scholar^.^ It is a syncretistic doctrine (as is usual f in times o basic uncertainties), although its chief proponents formulate it as the most universal that may be found in mankinds history. RenC GuCnon and his many

disciples-among whom F. Schuon, M. Eliade, and various students o alchemy, f neoPlatonism, astrology, symbologyposit a Great Tradition, as old as mankind, which used to be omnipresent, but which has survived only in India, Tibet, and a few other places. It has also survived in old languages (Sanskrit, but also Greek, Latin, Aramaic, Persian, Celtic, etc.), old architectural designs, sacred rites and symbols, records o shamanism and f prophecy. This is not one tradition among many, but the ever-pervasive documentation of mans first and primeval contact with reality, the Ur-rlebniss, expressing that reality on every level of human/ divine manifestation. GuCnons works, today immensely influential, satisfy the most meticulous scholarly criteria as he traces etymologies, institutions, symbols, and ceremonies to the presence of the Great Tradition and its everywhere similar interpretations. The malaise that many, especially Christian, readers feel vis-a-vis GuCnon and his school is the quasi-gnostic air that permeates their writings. At the same time, the salvational aspect attracts many readers. For, after all, what is the secret of all gnoses? They present an incomparable antiquity, next to which all other beliefsystems are derivations, thus corrupted versions of the original dimmed lights, half-forgotten truths. The gnoses reach beyond history, to an ageless age when the numenon was directly experienced and its inspiration was immediately translated into communities and monuments capturing its spirit. We live, in comparison, in a desacralized age, a prosaic cycle, the iron age of Hesiod and Ovid, a profanized history in which the central religion, Christianity, also shares in the dramatic falling-away from Reality. No question that our contemporaries feel this drying-up of the numenal; sects proliferate, their adepts seeking salvation elsewhere than in Christianity: in charismatic movements, freemasonry, ecumenical syncretism, neopaganism, occult teachings, Marxism. Proofs are supplied (by GuCnon, J. Ellul, H.

218

Surnrner/FaN 1987

Corbin, J. Campbell, C. G. Jung-and I a m listing only the respectable sources) that Christianity, like monotheism in general, has been a deviation from the Other Tradition, a process of corrupting the Unspeakable Knowledge until it has been reduced to science, social engineering, the predominance of material concerns, secularization. The present state of Christianity and the civilization it has cosponsored with Greeks, Romans, and others-that is the crisis-is seen as proof o the inexorability of the last cycle f having descended on us, the (Hinduist) Kali-Yuga, after which the Great Tradition will be restored, but unrecognizably to our perception and to the presuppositions o f our obscured comprehension. In short, in the eyes of these thinkers, our age had rigidified the ancient corpus of beliefs into an idolatry, with God in exile-a fundamental gnostic tenet. The crisis is then self-perpetuating; in fact it deepens as the age of technology and o f superficial social systems forces the permanent symbols of the human race into oblivion. Nothing has a reference any more; the microcosm has been detached from the macrocosm, literature from myth, art from symbolization, science (gnosis) from sacred knowledge, astrology, alchemy. At this point we may correctly evaluate Jungs theory of the archetypes, which correspond to GuCnons forgotten worldsymbols, such as the wheel and its spokes, the flower (rose, lotus, lily), the concentric circles, the sacred mountain (pyramid, ziggurat, temples like the Javan Borobudur), the caves, labyrinths, the dome, the tree of life, the axis rnundi, and many more. We now acquire a better understanding of the gnosis as a total and salvational knowledge, immeasurably older than the upstart religions operating in daylight and jeopardizing the believers integration with God and the cosmos. As GuCnon writes, Rationalism reduces the individual to his own dimensions and deprives him of his faculties through which he would communicate with the transcendence. And the two forerunners were protestantism and humanism.G In another work:

We are witnessing the increase of distance from the basic principles, a process o degeneracy, a falling away from f eastern w i ~ d o m . ~reality, it is a wisdom In that ancient mankind possessed; its distilled essence is the conformity of the human order to the cosmic order that everything human must reflect. The notion that mankinds history is isolated from universal harmony is exclusively modern; it is in opposition to all the traditional concepts which assert the constant and necessary correlation between the cosmic and the human order.8 Jung, Jean Hani, Dupuy, Eliade, etc. speak basically the same language. What has been said of the Great Tradition, of the archetypes, of the cyclical mutations of the spirit, and of harmonies once known but now lost, suggests that not everybody suffers from the crisis I have been trying to delineate. Many regard Christianity as already thrown on the rubbish heap of cosmic metamorphoses; others deny its civilizational relevance; yet others, who claim to wish to reform it and save it from its own inherent temptations, push it into the arms of alien and devastating super-doctrines. At any rate, we have understood that a new, yet very ancient belief-system is making conquests among elite intellects. No more concrete proof of this is needed than the f confluence o todays master-disciplines, formulating the new creed and surrounding it with the prestige of both secrecy and depth. A very influential series of volumes, by Joseph C a m ~ b e l l , ~ brings further confirmation. In his Hero with a Thousand Faces (Bollingen Series, Princeton, 1949), Campbell states, after so many precursors, that when a civilization begins to reinterpret its mythology, the life goes out o it, temples become f museums. Precisely; by equating Christianity with a mythology, Campbell not only sees it as lifeless, but also contributes to its desiccation and demise. The thesis of his monumental work is that there is a vast unity of mythical searches for God, Whom we perceive through many and varied faces or masks. But the final

Modern Age

219

conclusion is that there i no God, only s masks, and that they are equivalent, in fact the same. The unity of all religions makes Christianity just another imitator arid replayer of older myths. In Occidental Mythology (vol. 3), hundreds of pages demonstrate the near-identity of Persian, Indian, Egyptian descriptions of how the Cod/prophet (Osiris, Zoroaster, Moses, Romulus, Oedipus, Buddha, Jesus)l0 was born under non-clarifiable circumstances, how he was in all the legends hidden, found, secretly brought up, returned among men, murdered, come back in glory. True, Campbell makes an exception for Jesus and Christianity as the only one of all religious heroes and religions that enter history concretely, spreading a personal and social message. This, however, if we consider Corbins judgment, is not necessarily an advantage: the turn from the esoteric and otherworldly to the exoteric contains the danger of secularization, o absorption in mundane concernsf the case finally and irreversibly of Catholicism, too, according to this great student of Persian Islam. Campbell documents on every point (something that Voltaires and Lessings generation did not have a t their disposal) the exact analogy of all the world religions/myths, even though he operates some cleavages, for example the East and the West, the demarcation line being Iran. The point is that he thus contributes to the fleshing out of the elite religion 1 have tried to identify in the foregoing. A characteristic passage, showing this investigative elites rise above religion-as-truth, is the following: In Mesopotamia, c. 2500, a psychology of mythic dissociation broke the old spell of the identity of man and the divine, which division was inherited by the later mythic systems of the West (Oriental Mythology, p. 500). And earlier: People sought to represent their intuitions of the Absolute beyond terms: in the West, we personify it as God, in the East it is depersonified as Being or as Non-Being (Idem, p. 313). One must say, at the risk of angering the Voegelinians, that their mentor would

have agreed: Voegelin spoke of the divine ground of being, a vague expression which does not explain (this is perhaps impossible) the psychology of mythic dissociation, the breakdown of the old spell of the identity of man and the divine. Behind the scholarly terms, this view points, for both Voegelin and Campbell, to an evolution from an original myth to a new psychology, that is, to a gradual interiorization of what was once believed to be the real.

Is THERE A CRISIS of our civilization! There is. We have attempted to trace its origin (the Germans have a better word for it: Entstehund from the political to the psychological to the religious levels. The main point is not whether the crisis is a decadence or whether, if so, it is reversible. As a historical phenomenon, it is evident that the crisis is felt on the level of the people and of the elite. It percolates down from the latter to the former, and as such it may be diagnosed as the subjectivization of all dimensions of reality. But is the soul of man-and his communitywhen unsupported from outside, from beyond, strong enough to carry this burden?

A recent case illuminates it. When in 1970 the Japanese writer Yukio Mishima committed hari-kari at the head of his private patriotic militia, he became a great embarrassment to modern, democratic, industrial Japan. The crisis for the young Mishima had come in 1946 when, on MacArthurs urging, the Emperor declared in public that he was not a divine person, but a mere human. This brutal de-mythification remained Mishimas obsession, and his hari-kari became a national atonement. *We see at once the reason for the modern dismissal of Plato and the preference given to Dionysos and the initiation mysteries. 3Needless to say, we must acknowledge the existence of a variety of psychological approaches. It seems, however, that the one proceeding from Jung and his school is the most influential, perhaps because it claims historical, philosophical, and religious dimensions. 4As it was in the second century, when St. Irenaeus wrote his standard work on the subject he observed first-hand, the Adversos f Hoereses. SSincethe publication o Raymond Ruyers Lo Cnose de Princeton, the group therein studied has become a kind of model for such groups of erudite

220

Surnrner/Fall I987

scientists. 6Le R&ne de la quonfitt! et l signa des a temps (Paris, 1945). p. 258. 7 h Crise du monde moderne (Paris, 1946). p. 18. Tormes trudifionnelles et cycles cosrniques (Paris, 1970). p. 14. If I quote Guenon more than once, it is because he is practically unknown in the United States, where his name is

pronounced, if at all, almost in an embarrassed whisper. gThe Masks of God, four volumes (New York, 1959-68). loone irresistibly thinks of another eclectic age, Romes third century, when in his private chapel the emperor Alexander Severus worshiped Abraham, Zoroaster, Jesus, Osiris, etc.

Modern Age

221

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- The Journey of the Dialectic: Knowing God, Volume 3Dari EverandThe Journey of the Dialectic: Knowing God, Volume 3Belum ada peringkat

- One Theologian's Personal Journey Reflecting on Faith and CultureDokumen13 halamanOne Theologian's Personal Journey Reflecting on Faith and CulturestjeromesBelum ada peringkat

- UntitledDokumen23 halamanUntitledbagheeraBelum ada peringkat

- William Most - Our Lady in Doctrine and DevotionDokumen154 halamanWilliam Most - Our Lady in Doctrine and DevotionMihai SarbuBelum ada peringkat

- The Destruction of The Christian Tradition (Part 1) (Rama P. Coomaraswamy) PDFDokumen27 halamanThe Destruction of The Christian Tradition (Part 1) (Rama P. Coomaraswamy) PDFIsraelBelum ada peringkat

- The Permanent Instruction of The Alta Vendita A Masonic Blueprint For The Subversion of The Catholic Church (VENNARI, John) (Z-Library)Dokumen64 halamanThe Permanent Instruction of The Alta Vendita A Masonic Blueprint For The Subversion of The Catholic Church (VENNARI, John) (Z-Library)Lee MwadimeBelum ada peringkat

- Richard A. Lebrun - Joseph de Maistre's Life, Thought, and Influence - Selected Studies-McGill-Queen's University Press (2001)Dokumen349 halamanRichard A. Lebrun - Joseph de Maistre's Life, Thought, and Influence - Selected Studies-McGill-Queen's University Press (2001)Narciss HamedBelum ada peringkat

- A Symbol Perfected in DeathDokumen16 halamanA Symbol Perfected in DeathFodor ZoltanBelum ada peringkat

- Weston Jesuit School of Theology Cambridge, Massachusetts: Book ReviewsDokumen7 halamanWeston Jesuit School of Theology Cambridge, Massachusetts: Book ReviewsD SBelum ada peringkat

- Philosophia Perennis - CoomaraswamyDokumen7 halamanPhilosophia Perennis - Coomaraswamy09yak85Belum ada peringkat

- 7 Catholic Church History Part II Viii-EndDokumen269 halaman7 Catholic Church History Part II Viii-EndQuo PrimumBelum ada peringkat

- Orthodoxy, Dogma, and The Neuralgic Question of Doctrinal DevelopmentDokumen23 halamanOrthodoxy, Dogma, and The Neuralgic Question of Doctrinal Developmentst iBelum ada peringkat

- Heretical Theologians and Books IdentifiedDokumen45 halamanHeretical Theologians and Books IdentifiedVinny MeloBelum ada peringkat

- On The Various Kinds of Distinctions Disputationes Annas ArchiveDokumen76 halamanOn The Various Kinds of Distinctions Disputationes Annas ArchiveBalteric BaltericBelum ada peringkat

- The Errors of RomanismDokumen9 halamanThe Errors of RomanismEric DacumiBelum ada peringkat

- Samuel Francis, "Beyond Conservatism"Dokumen5 halamanSamuel Francis, "Beyond Conservatism"Anonymous ZwwcxXBelum ada peringkat

- Foreward To "Encounter Between Eastern Orthodoxy and Radical Orthodoxy"Dokumen4 halamanForeward To "Encounter Between Eastern Orthodoxy and Radical Orthodoxy"akimelBelum ada peringkat

- CHHI 520 Constantine Research PaperDokumen15 halamanCHHI 520 Constantine Research PaperDebbie BaskinBelum ada peringkat

- Explanation of The ThesisDokumen11 halamanExplanation of The ThesisValentin WmontBelum ada peringkat

- Is Europe DyingDokumen5 halamanIs Europe DyingPiotr WójcickiBelum ada peringkat

- Palamas, Scotus, Aquinas, Their Schools and Byzantine MariologyDokumen22 halamanPalamas, Scotus, Aquinas, Their Schools and Byzantine MariologyMarcus Tullius CeceBelum ada peringkat

- Faith Imperiled by Reason (Edited)Dokumen103 halamanFaith Imperiled by Reason (Edited)anonymous2178Belum ada peringkat

- Plain Truth 1973 (Prelim No 10) Nov - WDokumen44 halamanPlain Truth 1973 (Prelim No 10) Nov - WTheWorldTomorrowTVBelum ada peringkat

- Germain Grisez - (1965) The First Principle of Practical Reason. A Commentary On Summa Theologiae, 1-2, Q. 94, A. 2. Natural Law Forum Vol. 10.Dokumen35 halamanGermain Grisez - (1965) The First Principle of Practical Reason. A Commentary On Summa Theologiae, 1-2, Q. 94, A. 2. Natural Law Forum Vol. 10.filosophBelum ada peringkat

- Christopher Dawson, Historian of Christian Divisions and Prophet of Christian UnityDokumen14 halamanChristopher Dawson, Historian of Christian Divisions and Prophet of Christian Unityrustycarmelina1080% (1)

- Sacramental Intention and Masonic Bishops: by Rev. Anthony CekadaDokumen8 halamanSacramental Intention and Masonic Bishops: by Rev. Anthony CekadaSparxzBelum ada peringkat

- Fallible Teachings and the Holy SpiritDokumen26 halamanFallible Teachings and the Holy SpiritdaPipernoBelum ada peringkat

- Converting ConstantineDokumen14 halamanConverting ConstantineGuaguanconBelum ada peringkat

- What The Reformation WasDokumen52 halamanWhat The Reformation WasFirmansyah YakuzaBelum ada peringkat

- Thomistic Philosophy An Introduction070618Dokumen13 halamanThomistic Philosophy An Introduction070618Steve BoteBelum ada peringkat

- Classical Western Philosophy: Introduction and OverviewDokumen9 halamanClassical Western Philosophy: Introduction and Overviewseeker890Belum ada peringkat

- The Mind Behind the Motu ProprioDokumen6 halamanThe Mind Behind the Motu ProprioMark MakowieckiBelum ada peringkat

- The Revisionist - Journal For Critical Historical Inquiry - Volume 1 - Number 2 (En, 2003, 124 S., Text)Dokumen124 halamanThe Revisionist - Journal For Critical Historical Inquiry - Volume 1 - Number 2 (En, 2003, 124 S., Text)hjuinixBelum ada peringkat

- The Third Testis ArticleDokumen29 halamanThe Third Testis ArticleSancrucensisBelum ada peringkat

- Absolute Military Monarchy in Place of A Feudal State or of A Republic of NotablesDokumen9 halamanAbsolute Military Monarchy in Place of A Feudal State or of A Republic of NotablesVon Erarich.Belum ada peringkat

- The Undermining of The Catholic Church (1991)Dokumen221 halamanThe Undermining of The Catholic Church (1991)luvpuppy_ukBelum ada peringkat

- Eric Voegelin's Immanentism - Maben Walter PoirierDokumen32 halamanEric Voegelin's Immanentism - Maben Walter PoirierAluysio AthaydeBelum ada peringkat

- Brennan - The Mansions of Thomistic PhilosophyDokumen13 halamanBrennan - The Mansions of Thomistic Philosophybosmutus100% (4)

- Lord Acton On The PapacyDokumen10 halamanLord Acton On The PapacyOxony19100% (1)

- Medicine Before ScienceDokumen298 halamanMedicine Before ScienceIsrael Martinez FotvideoBelum ada peringkat

- Mental Prayer According To The - Fahey, Denis, C.S.SP., D.D., D - 9433Dokumen72 halamanMental Prayer According To The - Fahey, Denis, C.S.SP., D.D., D - 9433Doctrix Metaphysicae100% (1)

- Erasmus Letter To LutherDokumen4 halamanErasmus Letter To Luthermatfox2Belum ada peringkat

- William Most - Commentary On The Pauline EpistlesDokumen309 halamanWilliam Most - Commentary On The Pauline EpistlesMihai Sarbu100% (1)

- Kozinski Modernity ApocalypseDokumen242 halamanKozinski Modernity ApocalypseThaddeusKozinskiBelum ada peringkat

- 4800ADTE040 de NovissimisDokumen62 halaman4800ADTE040 de NovissimisThomist AquinasBelum ada peringkat

- Architecture of Modern Political PowerDokumen257 halamanArchitecture of Modern Political PowerAldo Milla RiquelmeBelum ada peringkat

- A Critique of Rosalind Hursthouse's On Virtue Ethics PDFDokumen101 halamanA Critique of Rosalind Hursthouse's On Virtue Ethics PDFSamir DjokovicBelum ada peringkat

- Sanborn Response WilliamsonDokumen8 halamanSanborn Response WilliamsonAnonymous HtDbszqtBelum ada peringkat

- 281 The Holy New Martyrs of The Urals Siberia and Cen PDFDokumen284 halaman281 The Holy New Martyrs of The Urals Siberia and Cen PDFlaur5boldorBelum ada peringkat

- Scott Nearing (1927) - Economic Organisation of The Soviet Union PDFDokumen267 halamanScott Nearing (1927) - Economic Organisation of The Soviet Union PDFHoyoung ChungBelum ada peringkat

- Bede The Venerable - SpiritDokumen15 halamanBede The Venerable - SpiritkuttickattuBelum ada peringkat

- Anthony Cekada - Work of Human HandsDokumen465 halamanAnthony Cekada - Work of Human HandsDeimos StrifeBelum ada peringkat

- Molnar, Thomas - The Essence of Modernity (Scan) PDFDokumen8 halamanMolnar, Thomas - The Essence of Modernity (Scan) PDFnonamedesire555Belum ada peringkat

- Schall Metaphysics Theology and PTDokumen25 halamanSchall Metaphysics Theology and PTtinman2009Belum ada peringkat

- Woodrow Wilson On Socialism and DemocracyDokumen5 halamanWoodrow Wilson On Socialism and DemocracyJohn MalcolmBelum ada peringkat

- Mango, St. Michael and AttisDokumen25 halamanMango, St. Michael and AttisAndrei DumitrescuBelum ada peringkat

- The Roots of Leftism in ChristianityDokumen13 halamanThe Roots of Leftism in ChristianityPiano AquieuBelum ada peringkat

- The Necessity of Faith in Jesus Christ to Obtain SalvationDari EverandThe Necessity of Faith in Jesus Christ to Obtain SalvationBelum ada peringkat

- The Two Cultures and Scientific RevolutionDokumen32 halamanThe Two Cultures and Scientific RevolutionРатлїк ТэяяэшаттэBelum ada peringkat

- The Portrait of A Scholar, and Other EssaysDokumen156 halamanThe Portrait of A Scholar, and Other EssaysMaDzik MaDzikowskaBelum ada peringkat

- The Religious Situation in East AsiaDokumen4 halamanThe Religious Situation in East AsiaMaDzik MaDzikowskaBelum ada peringkat

- The Cameralists, The Pioneers of German Social PolityDokumen640 halamanThe Cameralists, The Pioneers of German Social PolityMaDzik MaDzikowskaBelum ada peringkat

- The Liberal HegemonyDokumen9 halamanThe Liberal HegemonyMaDzik MaDzikowskaBelum ada peringkat

- The New EmpireDokumen306 halamanThe New EmpireMaDzik MaDzikowskaBelum ada peringkat

- The Life of Science Essays in The History of CivilizationDokumen216 halamanThe Life of Science Essays in The History of CivilizationMaDzik MaDzikowskaBelum ada peringkat

- Rothbard, Karl Marx - Communist As Religious EschatologistDokumen57 halamanRothbard, Karl Marx - Communist As Religious EschatologistMaDzik MaDzikowskaBelum ada peringkat

- Kolakowski - Main Currents of Marxism, Vol. IIDokumen276 halamanKolakowski - Main Currents of Marxism, Vol. IIMaDzik MaDzikowska100% (5)

- MolnarDokumen8 halamanMolnarMaDzik MaDzikowskaBelum ada peringkat

- Sarton, Ancient ScienceDokumen132 halamanSarton, Ancient ScienceMaDzik MaDzikowskaBelum ada peringkat

- Ideas of Civil War in Seventeenth-Century EnglandDokumen8 halamanIdeas of Civil War in Seventeenth-Century EnglandMalgrin2012Belum ada peringkat

- Molnar, Myth and UtopiaDokumen7 halamanMolnar, Myth and UtopiaMaDzik MaDzikowska100% (1)

- On Camus and Capital PunishmentDokumen9 halamanOn Camus and Capital PunishmentMaDzik MaDzikowskaBelum ada peringkat

- Kolakowski, Main Currents of Marxism, Vol. IDokumen224 halamanKolakowski, Main Currents of Marxism, Vol. IMaDzik MaDzikowskaBelum ada peringkat

- Catholic Political Thought, 1789-1848Dokumen222 halamanCatholic Political Thought, 1789-1848MaDzik MaDzikowska100% (2)

- Gilson, The Spirit of Mediaeval PhilosophyDokumen494 halamanGilson, The Spirit of Mediaeval PhilosophyMaDzik MaDzikowskaBelum ada peringkat

- Europe's Fateful HourDokumen264 halamanEurope's Fateful HourMaDzik MaDzikowskaBelum ada peringkat

- A Sociology of NamesDokumen5 halamanA Sociology of NamesMaDzik MaDzikowskaBelum ada peringkat

- Thomas Molnar - Charles Maurras Shaper of An AgeDokumen6 halamanThomas Molnar - Charles Maurras Shaper of An AgeThomas MpourtzalasBelum ada peringkat

- CATHOLICS VS MASONS: THE CONFLICT OVER EDUCATION IN 19TH CENTURY AUSTRALIADokumen22 halamanCATHOLICS VS MASONS: THE CONFLICT OVER EDUCATION IN 19TH CENTURY AUSTRALIAmehr_ariaBelum ada peringkat

- A Guide To The History of Science A First Guide For The Study of The History of ScienceDokumen342 halamanA Guide To The History of Science A First Guide For The Study of The History of ScienceMaDzik MaDzikowska100% (2)

- Adam Smith and Modern Sociology, A Study in The Methodology of The Social SciencesDokumen268 halamanAdam Smith and Modern Sociology, A Study in The Methodology of The Social SciencesMaDzik MaDzikowskaBelum ada peringkat

- An Outline of The History of The Intellectual Class in Western EuropeDokumen72 halamanAn Outline of The History of The Intellectual Class in Western EuropeMaDzik MaDzikowskaBelum ada peringkat

- Bill Overview: Jlb9Hznfdskgxfivcivc Ykpfivba5Kywibxmvc4Ewpcaxgaf 7FDokumen5 halamanBill Overview: Jlb9Hznfdskgxfivcivc Ykpfivba5Kywibxmvc4Ewpcaxgaf 7FEric LauBelum ada peringkat

- Outpatient ClaimDokumen1 halamanOutpatient Claimtajuddin8Belum ada peringkat

- Common Terminology in Wireless NetworksDokumen15 halamanCommon Terminology in Wireless Networksabhishek4vishwakar-1Belum ada peringkat

- Accounts Project 1Dokumen35 halamanAccounts Project 1Pranaav PBelum ada peringkat

- Case Management OrderDokumen3 halamanCase Management OrderEquality Case FilesBelum ada peringkat

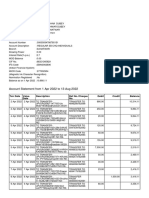

- Account Statement From 1 Apr 2022 To 13 Aug 2022: TXN Date Value Date Description Ref No./Cheque No. Debit Credit BalanceDokumen11 halamanAccount Statement From 1 Apr 2022 To 13 Aug 2022: TXN Date Value Date Description Ref No./Cheque No. Debit Credit BalanceShubham TyagiBelum ada peringkat

- P.E 3 The 6 Basic Skills of Volleyball All Varsity Players Should KnowDokumen7 halamanP.E 3 The 6 Basic Skills of Volleyball All Varsity Players Should KnowErika BiocarlesBelum ada peringkat

- Unit IIDokumen8 halamanUnit IIAlexander Vicente Jr.Belum ada peringkat

- Laudato Si NationalDokumen7 halamanLaudato Si NationalAngel AmarBelum ada peringkat

- 031 - The Russo-Japanese War 1904-05 PDFDokumen98 halaman031 - The Russo-Japanese War 1904-05 PDFMochammad Fadjar100% (5)

- NTH Month: Three Party Agreement Template - Docx Page 1 of 6Dokumen6 halamanNTH Month: Three Party Agreement Template - Docx Page 1 of 6Marvy QuijalvoBelum ada peringkat

- My New ResumeDokumen1 halamanMy New Resumeapi-412394530Belum ada peringkat

- EL 112 Week 4Dokumen41 halamanEL 112 Week 4salditoskriiusy100% (1)

- Employees Contributory Fund (Investment in Listed Securities) RegulationDokumen9 halamanEmployees Contributory Fund (Investment in Listed Securities) RegulationBabasmeatBelum ada peringkat

- Domestic Abuse and Bullying StatisticsDokumen8 halamanDomestic Abuse and Bullying Statisticsijohn1972100% (1)

- en 1 A Different ManDokumen31 halamanen 1 A Different ManVera Lucía Wurst GiustiBelum ada peringkat

- Innovation Index-2004 UpdateDokumen26 halamanInnovation Index-2004 UpdateJoshua GansBelum ada peringkat

- Let-It-Snow.-Ho-Ho-Ho Worksheet // Lesson PlanDokumen21 halamanLet-It-Snow.-Ho-Ho-Ho Worksheet // Lesson PlanМария НифонтоваBelum ada peringkat

- Cogzidel Consultancy Services Pvt Ltd Provident Fund Procedures Problems SolutionsDokumen122 halamanCogzidel Consultancy Services Pvt Ltd Provident Fund Procedures Problems Solutionsnewsletters4meBelum ada peringkat

- Voss FulltechDokumen14 halamanVoss FulltechUnifi HebatBelum ada peringkat

- Terms of Reference For The Conduct of FS For The Kabulnan 2 Multi Purpose Irrigation and Power ProjectDokumen32 halamanTerms of Reference For The Conduct of FS For The Kabulnan 2 Multi Purpose Irrigation and Power ProjectMelikteBelum ada peringkat

- 2022 Jeffrey Cheah Ace Scholarship InfoDokumen1 halaman2022 Jeffrey Cheah Ace Scholarship InfoLee Sun TaiBelum ada peringkat

- Article 49-3 de La Constitution DissertationDokumen8 halamanArticle 49-3 de La Constitution DissertationBuyPaperOnlineUK100% (1)

- Tata 1MG Application FormDokumen1 halamanTata 1MG Application Formparthaji1991Belum ada peringkat

- Event Marketing Research and PlanningDokumen72 halamanEvent Marketing Research and PlanninggopikaBelum ada peringkat

- Reply Brief in Support of Apple's Motion To VacateDokumen33 halamanReply Brief in Support of Apple's Motion To VacateKif Leswing0% (1)

- Atp Program DetailsDokumen9 halamanAtp Program DetailsAhmed BernoussiBelum ada peringkat

- UCSP Political ScienceDokumen42 halamanUCSP Political ScienceOnyxSungaBelum ada peringkat

- E Business InfrastructureDokumen26 halamanE Business InfrastructureankitjhaBelum ada peringkat

- Eat Kangaroo To Save The PlanetDokumen1 halamanEat Kangaroo To Save The PlanetAna MariaBelum ada peringkat