Chapter 08 Andrew Beveridge

Diunggah oleh

Pintu AhmedDeskripsi Asli:

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Chapter 08 Andrew Beveridge

Diunggah oleh

Pintu AhmedHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

To Appear in Introduction to Sociology, Sixth Edition by Anthony Giddens, Mitchell Duneier, Richard P. Appelbaum. (New York: W.W.

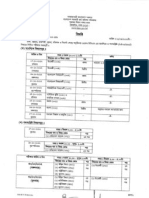

Norton, 2007) Chapter Eight: Stratification and Inequality Professor Andrew Beveridge

On Sunday morning of Labor Day weekend 2005, nearly two million copies of the New York Times were delivered to doorsteps around the country. Hurricane Katrina had on August 31st inflicted catastrophic damage on the central Gulf Coast, most notably by causing extensive flooding in New Orleans, Louisiana, and reporters like Jason DeParle were just beginning to make sense of the tragedy.

What a shocked world saw exposed in New Orleans last week wasn't just a broken levee. It was a cleavage of race and class, at once familiar and startlingly new, laid bare in a setting where they suddenly amounted to matters of life and death. Hydrology joined sociology throughout the story line, from the settling of the flood-prone city, where well-to-do white people lived on the high ground, to its frantic abandonment. No one was immune, of course. With 80 percent of the city under water, tragedy swallowed the privilege and poor, and traveled spread across racial lines. But the divides in the city were evident in things as simple as access to a car. The 35 percent of black households that didn't have one, compared with just 15 percent among whites. (DeParle, 2005).

On the same day, reporters were also grappling with inequality closer to home. With race and class debates already stirred into a frenzy by the hurricane, Sam Roberts broke news of rising inequality in Manhattan, home to the New York Times headquarters and over 1.6 million of the richest and poorest residents in America living side by side.

Trump Tower on Fifth Avenue is only about 60 blocks from the Wagner Houses in East Harlem, but they might as well be light years apart. They epitomize the highest- and lowest-earning census tracts in Manhattan, where the disparity between rich and poor is now greater than in any other county in the country. That finding, in an analysis conducted for The New York Times, dovetails with other new regional economic researchThe top fifth of earners in Manhattan now make 52 times what the lowest fifth make -- $365,826 compared with $7,047 -- which is roughly comparable to the income disparity in Namibia...Put another way, for every dollar made by households in the top fifth of Manhattan earners, households in the bottom fifth made about 2 cents (Roberts, 2005).

Much of what we read in newspapers consists of statisticsthat 35% of black households in New Orleans didnt have a car compared to just 15% of white households, that the top 20% of incomes in New York City average $365,826 compared to only $7,047 for the bottom fifth. These statistics reveal important patterns about race and class in America and help us understand how power is concentrated in our society. But where do these statistics come from? Is there somewhere that reporters like Jason DeParle and Sam Roberts can go to find reliable statistics about class and inequality in America? For the past 13 years, they have gone to Professor Andrew Beveridge, a professor of sociology at Queens College in New York City. Beveridge has a formal partnership with the New York Times to answer these questions and back them up with data. This partnership is a unique example of how a sociologist can help provide information to the public while framing that information in a sociological way. For example, in the days before and after Katrina hit the Gulf

Coast, millions of viewers around the country watched local residents pack the roadways in an effort to escape the storm. Many suspected that those trapped behind lacked access to a car, but who knew for sure? Reporters and news anchors were scrambling to find out the real story. For the answer, they contacted Professor Beveridge. On very short notice, he conducted and delivered a demographic analysis of the New Orleans area using U.S. Census data on car ownership. Within hours had produced the first solid statistics on the issue and helped work with reporters to craft their stories. In addition to using those statistics in articles, the staff at New York Times developed a graphic that helped illustrate to general readers that class inequality may have been what drove some to escape and others to drown. Harlem lies 1315 miles northeast of New Orleans on the island of Manhattan and houses many of New Yorks poorest residents living within walking distance of mansions (such as the DukeSemans townhouse) which sell for up to $50 million. Manhattan is known to attract some of the most talented and driven professionals from around the world, so it is not surprising that levels of inequality exist in New York City. Whats surprising is that those levels have increased dramatically over the past few decades. When Beveridge brought this to the attention of editors at the Times, they assigned reporters to the story immediately. Again using Census data for his analysis, Beveridge showed that as of the year 2000, the top fifth of earners made 52 times what the lowest make in Manhattan. Ten years earlier in 1990, the number for the top fifth was 32 times greater than the bottom fifth. In 1980, the difference was only a factor of 21. Over the past two decades, ''the gains are all going to the top,'' Dr. Beveridge said. ''It's a massive class disparity (Roberts, 2005). Professor Beveridge uses his role as a public sociologist to help the general public understand tough issues like class in America. Americans can (and often do) change their class positions over time, which makes class a difficult thing to understand. For example, although we know that money matters in America, its hard to draw lines that separate one class from another. This has led many academics to conclude that class distinctions do not exist in the U.S. like they do in other places. Beveridge has no patience for these dismissals. People can talk about class all they want, but its not until you see Katrina and these Manhattan statistics that you start to really understand what its like to be left behind in America. Far from diminishing, class has actually become more and more important over the past three decades. By emphasizing not only income but education, prestige, and wealth, Beveridge helps bring a sociological understanding to class analysis. He takes his partnership with the Times very seriously, viewing it as a way to bridge a gap between science and public understanding. Thats why Beveridge was asked to join high-level editorial meetings to plan out a ten-part series on Class in America during the summer of 2005. Thats why Beveridge has been asked repeatedly to testify in court as an expert witness in neighborhood and community disputes. Thats why by 2005 Beveridge had authored over 50 articles for GothamGazette.com, a nonprofit Web site about the issues facing New York City, and contributed analyses for over 40 New York Times articles over the past decade. By selecting and analyzing data he considers important to society, Beveridge not only influences newsmakers but helps to create the news itself.

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- Rising Extreemism in BanglaeshDokumen11 halamanRising Extreemism in BanglaeshPintu AhmedBelum ada peringkat

- GPA Equivalency in BangladeshDokumen1 halamanGPA Equivalency in BangladeshPintu AhmedBelum ada peringkat

- Installation Process of SPSS PDFDokumen1 halamanInstallation Process of SPSS PDFPintu AhmedBelum ada peringkat

- Bcs Viva PreparationDokumen23 halamanBcs Viva PreparationPintu AhmedBelum ada peringkat

- Anthony Giddens - Modernity and Self-IdentityDokumen5 halamanAnthony Giddens - Modernity and Self-IdentityPintu Ahmed100% (2)

- Reflection On An Alternative Feasible Criminal Justice Model by The Context of BangladeshDokumen57 halamanReflection On An Alternative Feasible Criminal Justice Model by The Context of BangladeshPintu Ahmed100% (1)

- Written Exam Schedule For The 33rd BCS Examination, BangladeshDokumen4 halamanWritten Exam Schedule For The 33rd BCS Examination, BangladeshPintu AhmedBelum ada peringkat

- Justice PNDokumen5 halamanJustice PNPintu AhmedBelum ada peringkat

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5794)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (344)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (587)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (73)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (265)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)

- Connotative and Denotative, Lexical and StylisticDokumen3 halamanConnotative and Denotative, Lexical and StylisticEman Jay FesalbonBelum ada peringkat

- Types, Shapes and MarginsDokumen10 halamanTypes, Shapes and MarginsAkhil KanukulaBelum ada peringkat

- Mil PRF 46010FDokumen20 halamanMil PRF 46010FSantaj Technologies100% (1)

- F77 - Service ManualDokumen120 halamanF77 - Service ManualStas MBelum ada peringkat

- Lawson v. Mabrie Lawsuit About Botched Funeral Service - October 2014Dokumen9 halamanLawson v. Mabrie Lawsuit About Botched Funeral Service - October 2014cindy_georgeBelum ada peringkat

- Reserve Management Parts I and II WBP Public 71907Dokumen86 halamanReserve Management Parts I and II WBP Public 71907Primo KUSHFUTURES™ M©QUEENBelum ada peringkat

- Activity 1: 2. Does His Homework - He S 3 Late ForDokumen10 halamanActivity 1: 2. Does His Homework - He S 3 Late ForINTELIGENCIA EDUCATIVABelum ada peringkat

- Aerospace Propulsion Course Outcomes and Syllabus OverviewDokumen48 halamanAerospace Propulsion Course Outcomes and Syllabus OverviewRukmani Devi100% (2)

- Ethical ControlDokumen28 halamanEthical ControlLani Derez100% (1)

- OCFINALEXAM2019Dokumen6 halamanOCFINALEXAM2019DA FT100% (1)

- Munslow, A. What History IsDokumen2 halamanMunslow, A. What History IsGoshai DaianBelum ada peringkat

- Tahap Kesediaan Pensyarah Terhadap Penggunaan M-Pembelajaran Dalam Sistem Pendidikan Dan Latihan Teknik Dan Vokasional (TVET)Dokumen17 halamanTahap Kesediaan Pensyarah Terhadap Penggunaan M-Pembelajaran Dalam Sistem Pendidikan Dan Latihan Teknik Dan Vokasional (TVET)Khairul Yop AzreenBelum ada peringkat

- Project Notes PackagingDokumen4 halamanProject Notes PackagingAngrej Singh SohalBelum ada peringkat

- Gallbladder Removal Recovery GuideDokumen14 halamanGallbladder Removal Recovery GuideMarin HarabagiuBelum ada peringkat

- Colorectal Disease - 2023 - Freund - Can Preoperative CT MR Enterography Preclude The Development of Crohn S Disease LikeDokumen10 halamanColorectal Disease - 2023 - Freund - Can Preoperative CT MR Enterography Preclude The Development of Crohn S Disease Likedavidmarkovic032Belum ada peringkat

- Stakeholder Management Plan Case Study 1Dokumen2 halamanStakeholder Management Plan Case Study 1Krister VallenteBelum ada peringkat

- Margiela Brandzine Mod 01Dokumen37 halamanMargiela Brandzine Mod 01Charlie PrattBelum ada peringkat

- Eclipse Phase Ghost in The ShellDokumen27 halamanEclipse Phase Ghost in The ShellMeni GeorgopoulouBelum ada peringkat

- Doctrine of Double EffectDokumen69 halamanDoctrine of Double Effectcharu555Belum ada peringkat

- Pratt & Whitney Engine Training ResourcesDokumen5 halamanPratt & Whitney Engine Training ResourcesJulio Abanto50% (2)

- Is the Prime Minister Too Powerful in CanadaDokumen9 halamanIs the Prime Minister Too Powerful in CanadaBen YuBelum ada peringkat

- Innovations in Teaching-Learning ProcessDokumen21 halamanInnovations in Teaching-Learning ProcessNova Rhea GarciaBelum ada peringkat

- Folk Tales of Nepal - Karunakar Vaidya - Compressed PDFDokumen97 halamanFolk Tales of Nepal - Karunakar Vaidya - Compressed PDFSanyukta ShresthaBelum ada peringkat

- NGOs Affiliated To SWCDokumen2.555 halamanNGOs Affiliated To SWCMandip marasiniBelum ada peringkat

- AMSY-6 OpManDokumen149 halamanAMSY-6 OpManFernando Piñal MoctezumaBelum ada peringkat

- Gert-Jan Van Der Heiden - 'The Voice of Misery - A Continental Philosophy of Testimony' PDFDokumen352 halamanGert-Jan Van Der Heiden - 'The Voice of Misery - A Continental Philosophy of Testimony' PDFscottbrodieBelum ada peringkat

- Labor DoctrinesDokumen22 halamanLabor DoctrinesAngemeir Chloe FranciscoBelum ada peringkat

- Firewalker Spell and Ability GuideDokumen2 halamanFirewalker Spell and Ability GuideRon Van 't VeerBelum ada peringkat

- 2017 Climate Survey ReportDokumen11 halaman2017 Climate Survey ReportRob PortBelum ada peringkat

- Advproxy - Advanced Web Proxy For SmoothWall Express 2.0 (Marco Sondermann, p76) PDFDokumen76 halamanAdvproxy - Advanced Web Proxy For SmoothWall Express 2.0 (Marco Sondermann, p76) PDFjayan_Sikarwar100% (1)