Check Against Delivery: English Version

Diunggah oleh

CBCPoliticsDeskripsi Asli:

Judul Asli

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Check Against Delivery: English Version

Diunggah oleh

CBCPoliticsHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

ENGLISH VERSION

Check against delivery

NOTES FOR AN OPENING STATEMENT BY MR. MARC BOSC, DEPUTY CLERK OF THE HOUSE OF COMMONS, BEFORE THE STANDING COMMITTEE ON PROCEDURE AND HOUSE AFFAIRS TUESDAY, OCTOBER 16, 2012 REGARDING PARLIAMENTARY PRIVILEGE AND ACCESS TO INFORMATION REQUESTS MADE TO OTHER PARTIES

October 16, 2012

Introduction

On behalf of the Clerk of the House, Audrey OBrien, who is unable to be here today, I would like to thank the Committee for inviting me to appear today regarding parliamentary privilege and access to information requests made to other parties. I am accompanied by Richard Denis, Deputy Law Clerk and Parliamentary Counsel.

My purpose in appearing before you is to review some of the basic concepts of parliamentary privilege, with a particular emphasis on what has traditionally been considered to constitute a proceeding in Parliament, the key concept of interest in the matter before the Committee. I would also like to outline a series of broad considerations the Committee may wish to take into account in pursuing its study.

Let me begin by returning to the statement made by the Speaker to the House on September 17 after the House, by unanimous consent, had passed a motion to waive its privileges in a

particular access to information case. He described the facts of the case and the series of events that have led us here this morning.

Let me turn first to the outline of certain fundamental tenets of parliamentary privilege. The Speaker states, at page 10005 of Debates:

The privileges, powers and immunities of the House of Commons, as provided by section 18 of the Constitution Act, 1867 and section 4 of the Parliament of Canada Act, include freedom of speech and debate as set out, among others places, in article 9 of the Bill of Rights, 1689, which provides that: the freedom of speech and debates or proceedings in Parliament, ought not to be impeached or questioned in any court or place out of Parliament.

As Erskine May's 24th edition, at page 227, states: underlying the Bill of Rights is the privilege of both Houses to the exclusive cognizance of their own proceedings. Both Houses retain the right to be sole judge of the lawfulness of

their own proceedings and to settleor depart fromtheir own codes of procedure.

House of Commons Procedure and Practice, at pages 91 and 92, explains that proceedings in Parliament include the giving of evidence before the House of Commons or its committees; the presentation of a document to either the House of Commons or its committees; the preparation of a document for purposes of or incidental to the transacting of any such business; and the formulation, making or publication of a document, including a report, by or pursuant to an order of the House. This has been seen to extend to all evidence, submissions and preparation for the participation by all persons participating in the proceedings of the House of Commons or its committees, all of which are protected by all the privileges and immunities of the House.

Writing of parliamentary privilege and what constitutes proceedings in Parliament, Joseph Maingots Parliamentary Privilege in Canada, Second Edition, at page 80 states:

Privilege of Parliament is founded on necessity, and is those rights that are "absolutely necessary for the due execution of its powers". Arguably, necessity should be a basis for any claim that an event was part of a "proceeding in Parliament", i.e., what is claimed to be part of a "proceeding in Parliament" and thus protected should be necessarily incidental to a "proceeding in Parliament.

Maingot goes on to emphasize that: As a technical parliamentary term, "proceedings" are the events and the steps leading up to some formal action, including a decision, taken by the House in its collective capacity. All of these steps and events, the whole process by which the House reaches a decision (the principal part of which is called debate), are "proceedings."

As Members of the Committee are aware, although House of Commons committees are not subject to the Access to Information Act, they are sometimes given third party notice under section 27 of the Act, in relation to access to information requests made of government departments or other agencies that are subject to the

provisions of the Act. What has traditionally happened is that the department or agency is informed that the information in question, because it forms part of a parliamentary proceeding, is protected by parliamentary privilege and thus should not be released by them under the Act. That is where the matter usually ends.

What the House did in adopting its resolution on September 17, 2012, was to agree to withdraw its objection to the release of information in one case. In other words, the House chose not to invoke its privileges in this instance. Speaker Scheer reminded Members that:

[...] this decision applies only to this case at hand and it is not precedent setting. The House's rights and privileges have not been jeopardized by the House's resolution, nor has the House ceded any of its traditional rights or privileges, particularly as they relate to parliamentary committees.

The Speakers statement confirms that the resolution does nothing to diminish the scope of its privileges, as the House understands them, in similar cases that may arise in the future but, as

well, that the privileges and immunities of the House of Commons must be affirmed and protected. The House remains free and unfettered to exercise its privilege to insist that certain documents and communications not be disclosed or published by another party.

However, as the Speaker indicated, House committees and their officials will most likely continue to be confronted with this kind of third party request. At the same time, we know that only the House can decide whether it will not insist on its privileges or whether it will enforce them. Accordingly, one way to examine the issue before you is to ask: is there a different, simpler way for parliamentarians, particularly those sitting on committees, to consider such third party requests?

I need to point out that we are referring here only to documents that are requested of departments and agencies, where these departments and agencies have the documents in their possession; we are not talking about the full range of committee documents.

I said earlier that House Administration officials have regularly responded to such requests first by determining if the material

requested was part of a parliamentary proceeding and, if so, explaining that the material was covered by parliamentary privilege and could not be released. This was widely accepted by departments and agencies and posed no difficulties. I need to stress that the material requested in many of these cases was already publicly available so it is not confidentiality that is the concern, it is the privileged nature of the proceedings.

Should the Committee want to modify what has been the traditional approach, it may want to recommend a process which would allow expeditious handling of ATIP requests of this nature. However, I would caution the Committee to remain mindful of the potential risks to House committees with respect to such access to information requests.

Let me outline a few areas of concern. 1. Confidential Procedural Advice Correspondence between the Committee Clerk and the Chair, Parliamentary Secretary, Committee Members or Department Officials could reveal the content of procedural advice regarding

the discussions or negotiations relating to the admissibility or the disposal of a motion or amendment to a bill.

2. Witnesses Correspondence between the Committee Clerk and the Chair, the Parliamentary Secretary, Department Officials, or the witness could reveal the content of discussions on plans, questions, intentions or decisions of the committee regarding the selection of witnesses. Correspondence containing various iterations of a witnesss speaking notes, brief or documentation before his/her appearance before a committee could cause harm to his/her reputation or reveal information that would otherwise have remained private. Witnesses could be reluctant to share this information ahead of time if there was a fear that it could become public later on.

3. Privacy Issues Correspondence between the Committee Clerk and a witness who refuses to or cannot appear (e.g., for health reasons) and

gives the reason in the said correspondence could reveal personal information about the witness.

4. Disclosure of Elements of a Committee Report: Correspondence between the Committee Clerk and/or the Chair with a witness regarding the content or potential recommendations of a report could reveal elements of the report that were considered but not adopted by the committee or discussed during an in camera meeting.

5. Committee Decisions / Plans: Decisions made by the committee during an in camera meeting or that do not appear in the Minutes of the committee meeting could be traced through correspondence (e.g. e-mails between Department Officials, the Parliamentary Secretary, and the Committee Clerk before or after the meeting). Correspondence between Department Officials and the Committee Clerk could reveal sensitive information regarding a committees travel plans, subjects it is studying or matters it is

10

interested in pursuing. In certain cases, this could involve issues dealing with national security or compromise the security of Members (e.g. travel to a military base in Afghanistan).

These are very general concerns that I am putting before you. They are not insurmountable and I am confident that substantive discussions among members of this Committee could lead to helpful recommendations on a proposed course of action.

I will close by suggesting to the Committee that any proposed approach to deal with this issue should include, as an underlying principle, the protection of the privileges of the House and its Members, and by extension of those of its committees and its witnesses. In fact, I believe that in so doing the Committee could make a significant contribution to House of Commons practice, allowing it to evolve to meet expectations on transparency, while protecting its fundamental rights and privileges.

11

Our role as House officials will be to support you in this process and to ensure that you have available to you all the relevant information necessary to make the appropriate recommendations.

Thank you for your attention. The Deputy Law Clerk and I are now ready to answer any questions you may have.

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- Reed's Parliamentary Rules: A Manual of General Parliamentary LawDari EverandReed's Parliamentary Rules: A Manual of General Parliamentary LawBelum ada peringkat

- Parliamentary Lessons: based on "Reed's Rules Of Order," A handbook Of Common Parliamentary LawDari EverandParliamentary Lessons: based on "Reed's Rules Of Order," A handbook Of Common Parliamentary LawPenilaian: 2 dari 5 bintang2/5 (1)

- Check Against Delivery: English VersionDokumen5 halamanCheck Against Delivery: English VersionCBCPoliticsBelum ada peringkat

- Parliamentary Privilege UK 2012 AprilDokumen88 halamanParliamentary Privilege UK 2012 Aprilmary eng0% (1)

- By Email: Our File 1351Dokumen5 halamanBy Email: Our File 1351kady23Belum ada peringkat

- Natural Justice 2010Dokumen33 halamanNatural Justice 2010foo77Belum ada peringkat

- Privileges 1Dokumen15 halamanPrivileges 1Ebadur RahmanBelum ada peringkat

- Nicholson Intervention - Question of Privilege ENGDokumen20 halamanNicholson Intervention - Question of Privilege ENGkady_omalley5260Belum ada peringkat

- Unit 5: Parliamentary Committee and The Law Making ProcessDokumen9 halamanUnit 5: Parliamentary Committee and The Law Making ProcessSajanBentennisonBelum ada peringkat

- Nominations Report - FINALDokumen87 halamanNominations Report - FINALKenya National AssemblyBelum ada peringkat

- PAPER On PARLIAMENTARY PRIVILEGE - 23 Conference of Speakers and Presiding Officers, MalaysiaDokumen15 halamanPAPER On PARLIAMENTARY PRIVILEGE - 23 Conference of Speakers and Presiding Officers, MalaysiafisekotashaBelum ada peringkat

- Parliament and Its Members" and Article 194 Relating To The State Legislatures andDokumen15 halamanParliament and Its Members" and Article 194 Relating To The State Legislatures andmanideep reddyBelum ada peringkat

- Parliamentary Privilege: Complementary Role of The InstitutionsDokumen17 halamanParliamentary Privilege: Complementary Role of The InstitutionsSwasti MisraBelum ada peringkat

- Basic Statutory Construction and Legal TechniqueDokumen8 halamanBasic Statutory Construction and Legal TechniquePonce GuerreroBelum ada peringkat

- Alex Salmond Final SubmissionDokumen26 halamanAlex Salmond Final SubmissionCrawford BoydBelum ada peringkat

- GS 403 Answer FormatDokumen26 halamanGS 403 Answer FormatVamshi Krishna MallelaBelum ada peringkat

- Why A Separation of Power in Government Its Importance To ConstitutionalismDokumen6 halamanWhy A Separation of Power in Government Its Importance To ConstitutionalismmaccaferriasiaBelum ada peringkat

- External Aids To Interpretation and Construction - Notes of DiscussionDokumen12 halamanExternal Aids To Interpretation and Construction - Notes of DiscussionsanchiBelum ada peringkat

- LSI - Cherry Miller Background and IssuesDokumen10 halamanLSI - Cherry Miller Background and IssuesadrianleonewongBelum ada peringkat

- Final Call For Evidence Legislative ProcessDokumen4 halamanFinal Call For Evidence Legislative ProcessAARZOO KHANBelum ada peringkat

- Unit 5: Legislation: Learning Objectives Defining LegislationDokumen7 halamanUnit 5: Legislation: Learning Objectives Defining LegislationRoneil Quban WalkerBelum ada peringkat

- WARNING!!! This Case Digest Is Rather Long (6pages) Because of The Relevant Discussion of The Court As To The Subject For RecitationDokumen9 halamanWARNING!!! This Case Digest Is Rather Long (6pages) Because of The Relevant Discussion of The Court As To The Subject For RecitationGene HermosadoBelum ada peringkat

- Dr. Ram Manohar Lohia National Law University, Lucknow: B.A. LL.B. (4th Semester) Roll No.-149Dokumen11 halamanDr. Ram Manohar Lohia National Law University, Lucknow: B.A. LL.B. (4th Semester) Roll No.-149Stuti SinhaBelum ada peringkat

- Tom Marquardt Editor and Publisher Capital-Gazette CommunicationsDokumen7 halamanTom Marquardt Editor and Publisher Capital-Gazette CommunicationsCraig O'DonnellBelum ada peringkat

- Legislative Process - How A Bill Becomes A Law: (Intro - 1 Reading)Dokumen2 halamanLegislative Process - How A Bill Becomes A Law: (Intro - 1 Reading)yeeerualBelum ada peringkat

- Debate Over Parliamentary Privileges and Fundamental RightsDokumen16 halamanDebate Over Parliamentary Privileges and Fundamental RightsHarsh GautamBelum ada peringkat

- 1!.jouse of L/epresentattbe5': WmasbingtonDokumen5 halaman1!.jouse of L/epresentattbe5': WmasbingtonCorruptCongressBelum ada peringkat

- Parliamentary PrivilegesDokumen18 halamanParliamentary PrivilegesjoyBelum ada peringkat

- Law Test June 9thDokumen2 halamanLaw Test June 9thNivneth PeirisBelum ada peringkat

- DocumentDokumen5 halamanDocumentNorman jOyeBelum ada peringkat

- Parliamentary ProcedureDokumen27 halamanParliamentary ProcedureShawn Mhar Medina100% (2)

- List of Acts Passed by NASS in 2016Dokumen6 halamanList of Acts Passed by NASS in 2016Onyenaturuchi DavidBelum ada peringkat

- Consti ProjDokumen13 halamanConsti ProjAviral ChandraaBelum ada peringkat

- Basics of Legislation ProjectDokumen21 halamanBasics of Legislation ProjectJayantBelum ada peringkat

- Test Bank For Fundamentals of Taxation 2021 Edition 14th Edition Ana Cruz Michael Deschamps Frederick Niswander Debra Prendergast Dan SchislerDokumen33 halamanTest Bank For Fundamentals of Taxation 2021 Edition 14th Edition Ana Cruz Michael Deschamps Frederick Niswander Debra Prendergast Dan Schislercrincumose.at2d100% (44)

- The Commission of Inquiry ActDokumen8 halamanThe Commission of Inquiry ActHarsh VermaBelum ada peringkat

- 101 - Neri v. Senate Committee PDFDokumen4 halaman101 - Neri v. Senate Committee PDFMarl Dela ROsaBelum ada peringkat

- Laws Made by Parliament by BookDokumen5 halamanLaws Made by Parliament by BookMohsin MuhaarBelum ada peringkat

- Legislative History (At Iba Pa) : Group 2 Basil - Canta - Daweg - Liagon Par-Ogan - TumiguingDokumen71 halamanLegislative History (At Iba Pa) : Group 2 Basil - Canta - Daweg - Liagon Par-Ogan - TumiguingKatharina CantaBelum ada peringkat

- Parliament Bill ModelDokumen6 halamanParliament Bill Modelapi-235705348Belum ada peringkat

- Holds in SenateDokumen11 halamanHolds in SenateStephen LemonsBelum ada peringkat

- in Re Production of Court Records and DocumentsDokumen8 halamanin Re Production of Court Records and DocumentsNelly Herrera100% (1)

- Preparation of The BillDokumen9 halamanPreparation of The BillDha CapinigBelum ada peringkat

- Parliamentary Privilege and Freedom of SpeechDokumen21 halamanParliamentary Privilege and Freedom of Speechkuldeep garg100% (2)

- Zambian Sources of Law DmeDokumen10 halamanZambian Sources of Law DmeDaniel MukelabaiBelum ada peringkat

- 1975 - Black Clawson V Papierworke PDFDokumen21 halaman1975 - Black Clawson V Papierworke PDFAnnadeJesusBelum ada peringkat

- Daily News Simplified - DNS NotesDokumen10 halamanDaily News Simplified - DNS NotesNitinBelum ada peringkat

- Dr. Ram Manohar Lohiya National Law UniversityDokumen18 halamanDr. Ram Manohar Lohiya National Law UniversityJayantBelum ada peringkat

- Parliamentary Privileges and The Fundamental Right To Free SpeechDokumen12 halamanParliamentary Privileges and The Fundamental Right To Free SpeechAnkit ChauhanBelum ada peringkat

- CopytDokumen29 halamanCopytYousuf MohdBelum ada peringkat

- Per Curiam Decision of The SC in Connection With The LetterDokumen3 halamanPer Curiam Decision of The SC in Connection With The LetterJoshua AbadBelum ada peringkat

- Sources and Types of Legislative HistoryDokumen2 halamanSources and Types of Legislative HistoryEthel Joi Manalac MendozaBelum ada peringkat

- 20BALLB106 Constitutional Law-I Mid Term AssignmentDokumen13 halaman20BALLB106 Constitutional Law-I Mid Term AssignmentFida NavaZBelum ada peringkat

- Cash For Query ProjectDokumen33 halamanCash For Query Projectrijoy666Belum ada peringkat

- Parliamentary Privilege: Current IssuesDokumen27 halamanParliamentary Privilege: Current IssuesSabrine TravistinBelum ada peringkat

- House Hearing, 110TH Congress - Voting in The House of Representatives - Rules, Procedures, Precedents, Customs and PracticeDokumen44 halamanHouse Hearing, 110TH Congress - Voting in The House of Representatives - Rules, Procedures, Precedents, Customs and PracticeScribd Government DocsBelum ada peringkat

- Conn. General AssemblyDokumen5 halamanConn. General AssemblyMatthew IrwinBelum ada peringkat

- Parliament and Legislative Scrutiny: An Overview of Issues in The Legislative Process, Lord Norton of LouthDokumen3 halamanParliament and Legislative Scrutiny: An Overview of Issues in The Legislative Process, Lord Norton of LouthNameera AhmedBelum ada peringkat

- 01 Zimbabwe - S Legal SystemDokumen19 halaman01 Zimbabwe - S Legal SystemMacjim Frank88% (17)

- HPSCI Meeting TranscriptDari EverandHPSCI Meeting TranscriptBelum ada peringkat

- Federal Court Ruling On Council of Canadians Robocall CaseDokumen100 halamanFederal Court Ruling On Council of Canadians Robocall CaseCBCPoliticsBelum ada peringkat

- Letter From UN Women Canada To Minister Rona AmbroseDokumen2 halamanLetter From UN Women Canada To Minister Rona AmbroseCBCPoliticsBelum ada peringkat

- House of Commons Debates - 34-2-1989!10!10 - Speaker's DecisionDokumen6 halamanHouse of Commons Debates - 34-2-1989!10!10 - Speaker's DecisionCBCPoliticsBelum ada peringkat

- TOEWSCyber eDokumen4 halamanTOEWSCyber eCBCPoliticsBelum ada peringkat

- 2011-218A - Gravenhurst - G8 Legacy FundDokumen437 halaman2011-218A - Gravenhurst - G8 Legacy FundCBCPoliticsBelum ada peringkat

- CLEMENT Transcript EngDokumen3 halamanCLEMENT Transcript EngCBCPoliticsBelum ada peringkat

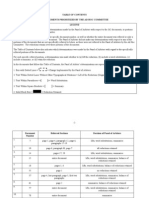

- Afghan Detainee Documents: Legend and Table of ContentsDokumen31 halamanAfghan Detainee Documents: Legend and Table of ContentsCBCPoliticsBelum ada peringkat

- State of The Nation 2010: Imagination To Innovation, Building Canadian Paths To ProsperityDokumen86 halamanState of The Nation 2010: Imagination To Innovation, Building Canadian Paths To ProsperityCBCPoliticsBelum ada peringkat

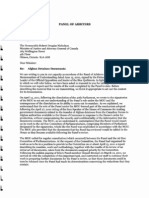

- Afghan Detainees Arbiters: April Report - Revised English Version - SIGNED With AppendixDokumen32 halamanAfghan Detainees Arbiters: April Report - Revised English Version - SIGNED With AppendixCBCPoliticsBelum ada peringkat

- Afghan Detainees Panel Letter - June 15 2011Dokumen3 halamanAfghan Detainees Panel Letter - June 15 2011CBCPoliticsBelum ada peringkat

- Muhammad Naseem KhanDokumen2 halamanMuhammad Naseem KhanNasim KhanBelum ada peringkat

- First Summative Test in TLE 6Dokumen1 halamanFirst Summative Test in TLE 6Georgina IntiaBelum ada peringkat

- Problem Solving and Decision MakingDokumen14 halamanProblem Solving and Decision Makingabhiscribd5103Belum ada peringkat

- SPED-Q1-LWD Learning-Package-4-CHILD-GSB-2Dokumen19 halamanSPED-Q1-LWD Learning-Package-4-CHILD-GSB-2Maria Ligaya SocoBelum ada peringkat

- 2nd Prelim ExamDokumen6 halaman2nd Prelim Exammechille lagoBelum ada peringkat

- Lectio Decima Septima: de Ablativo AbsoluteDokumen10 halamanLectio Decima Septima: de Ablativo AbsoluteDomina Nostra FatimaBelum ada peringkat

- Timeline of American OccupationDokumen3 halamanTimeline of American OccupationHannibal F. Carado100% (3)

- NSBM Student Well-Being Association: Our LogoDokumen4 halamanNSBM Student Well-Being Association: Our LogoMaithri Vidana KariyakaranageBelum ada peringkat

- Compsis at A CrossroadsDokumen4 halamanCompsis at A CrossroadsAbhi HarpalBelum ada peringkat

- ChinduDokumen1 halamanChinduraghavbiduru167% (3)

- Specific Relief Act, 1963Dokumen23 halamanSpecific Relief Act, 1963Saahiel Sharrma0% (1)

- Cantorme Vs Ducasin 57 Phil 23Dokumen3 halamanCantorme Vs Ducasin 57 Phil 23Christine CaddauanBelum ada peringkat

- 1 Summative Test in Empowerment Technology Name: - Date: - Year & Section: - ScoreDokumen2 halaman1 Summative Test in Empowerment Technology Name: - Date: - Year & Section: - ScoreShelene CathlynBelum ada peringkat

- La Bugal BLaan Tribal Association Inc. vs. RamosDokumen62 halamanLa Bugal BLaan Tribal Association Inc. vs. RamosAKnownKneeMouseeBelum ada peringkat

- The Giver Quiz 7-8Dokumen2 halamanThe Giver Quiz 7-8roxanaietiBelum ada peringkat

- Basic Priciples of GuidanceDokumen6 halamanBasic Priciples of GuidanceRuth ApriliaBelum ada peringkat

- PoetryDokumen5 halamanPoetryKhalika JaspiBelum ada peringkat

- EN 12953-8-2001 - enDokumen10 halamanEN 12953-8-2001 - enעקיבא אסBelum ada peringkat

- Annaphpapp 01Dokumen3 halamanAnnaphpapp 01anujhanda29Belum ada peringkat

- Councils of Catholic ChurchDokumen210 halamanCouncils of Catholic ChurchJoao Marcos Viana CostaBelum ada peringkat

- Proposed Food Truck LawDokumen4 halamanProposed Food Truck LawAlan BedenkoBelum ada peringkat

- Ijarah Tuto QnsDokumen3 halamanIjarah Tuto QnsSULEIMANBelum ada peringkat

- Transportation Systems ManagementDokumen9 halamanTransportation Systems ManagementSuresh100% (4)

- Henry Garrett Ranking TechniquesDokumen3 halamanHenry Garrett Ranking TechniquesSyed Zia-ur Rahman100% (1)

- Project Report On "Buying Behaviour: of Gold With Regards ToDokumen77 halamanProject Report On "Buying Behaviour: of Gold With Regards ToAbhishek MittalBelum ada peringkat

- DESIGNATIONDokumen16 halamanDESIGNATIONSan Roque ES (R IV-A - Quezon)Belum ada peringkat

- Louis I Kahn Trophy 2021-22 BriefDokumen7 halamanLouis I Kahn Trophy 2021-22 BriefMadhav D NairBelum ada peringkat

- Solar - Bhanu Solar - Company ProfileDokumen9 halamanSolar - Bhanu Solar - Company ProfileRaja Gopal Rao VishnudasBelum ada peringkat

- 1 s2.0 S0141391023000721 MainDokumen28 halaman1 s2.0 S0141391023000721 MainYemey Quispe ParedesBelum ada peringkat

- ReadmeDokumen2 halamanReadmeParthipan JayaramBelum ada peringkat