Diet and Sugar

Diunggah oleh

a_zuheirDeskripsi Asli:

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Diet and Sugar

Diunggah oleh

a_zuheirHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Diet and Sugar A poor diet high in sugars results in dental caries Dental caries can result in tooth

th loss Tooth loss reduces the ability to eat a healthy diet high in fruits and vegetables and fibre rich foods In many low-income countries, malnutrition coexists with a high sugar intake, such countries are at higher risk of dental caries The studies of Lady May Mellanby Showed that vitamin D deficiency impairs tooth development Concluded that the improved diet during the war years, with respect to vitamin and calcium intake was responsible for improved dental health Showed that enamel hypoplasia increased susceptibility to dental caries Showed that vitamin D supplementation reduced the incidence of dental caries in children The systemic effect of diet on dental caries Undernutrition is associated with hypoplasia of enamel which increases caries susceptibility Undernutrition results in salivary gland atrophy, reduced salivary flow rate, and reduced buffering capacitythese factors increase caries susceptibility Deficiency of vitamin D is associated with enamel hypoplasia and increased caries risk Undernutrition results in delayed shedding of the primary teeth and delayed eruption of the permanent teeth. This may influence the caries prevalence at a given age In undernourished populations where there is exposure to sugars in the diet, caries prevalence is higher than expected from observations in well-nourished populations Evidence for a relationship between diet and dental caries comes from different types of studies Human intervention studies (clinical trials) Human observational studies Animal experiments Plaque pH studies Enamel slab experiments Incubation studies Epidemiological studies of the sugars/caries relationship A positive relationship exists between per capita sugar availability and DMFT at age 12 years

A marked increase in the prevalence and severity of dental caries has been observed in populations who move away from their traditional way of eating and adopt a westernized diet, high in sugars Sub-groups of the population who habitually consume a high sugars diet have been shown to have higher levels of dental caries compared to the general population Sub-groups of the population who habitually consume a low sugars diet have been shown to have lower levels of dental caries compared with the general population Caution is needed when interpreting the findings of cross-sectional studies that have compared diet to levels of dental caries at one time point, since caries develops over time. It may be the diet several years previous which is responsible for current disease levels Studies with a longitudinal design, that measure diet and relate it to change in levels of dental caries over time provide stronger evidence Human intervention studies provide the strongest evidence for an association between diet and diseases, however, these are difficult to conduct from an ethical and logistic point of view Main conclusions of the Vipeholm study Sugar intake, even when consumed in large amounts, had little effect on caries increment if it was ingested up to a maximum of four times a day at mealtimes only Consumption of sugar in-between meals was associated with a marked increase in dental caries The increase in dental caries activity disappears on withdrawal of sugar-rich foods Dental caries experience showed wide individual variation

Animal studies have added to the knowledge of the sugars/caries relationship by showing: A clear relationship between frequency of consumption of a cariogenic diet and severity of dental caries Increasing caries with increasing sugars concentration Little difference in the cariogenicity of glucose, fructose and maltose and increased cariogenicity of sucrose only when animals are super infected with S. mutans Plaque pH studies Measure acidogenic potential, an indirect measure of cariogenicity

Measure the pH of plaque using either an indwelling electrode that measures pH in situ or by removing plaque samples and measuring the pH in vitro Acidogenicity is expressed as the area of the time/pH graph (Stephan curve), the minimum pH reached and/or the time for which pH drops below 5.5 (the critical pH) In summary There is evidence to show that both the frequency of intake of sugars and sugars-rich foods and drinks, and the total amount of sugars consumed are related to dental caries There is also evidence to show that these two variables are strongly associated, meaning that efforts to control one are likely to control the other It is public health policy to reduce the amount of sugars consumed At the level of the individual, it is more pragmatic to advise to reduce the frequency of consumption

Cariogenicity of sugars Sucrose, glucose, fructose, and maltose have similar cariogenicity Lactose is less acidogenic/cariogenic Physical location of sugars in foods effects their cariogenicity and sugars have been classified into intrinsic and extrinsic Intrinsic sugars are located within the cellular structure of the food and are not thought to be harmful to teeth

Extrinsic sugars are located outside the cellular structure of the food and include milk sugars and non-milk extrinsic sugars(free sugars) Milk sugars, when naturally present in milk or milk products, are not harmful to teeth Non-milk extrinsic sugars (free sugars) are the sugars that are harmful to teeth Dietary sugars and dental caries Sugars are the most cariogenic item in the diet The cariogenicity of sucrose, glucose, fructose, and maltose are similar but that of lactose is lower Frequency of eating is important, but frequency of eating sugarsrich foods and amount consumed are highly associated so that efforts to control one will control the other Reducing sugars consumption is an important part of caries prevention even when there is widespread exposure to fluoride Starches and dental caries Cooked staple starchy foods such as rice, potatoes, and bread are of low cariogenicity in humans The cariogenicity of uncooked starch is very low Finely ground and heat-treated starch may cause dental caries but the amount of caries is less than that caused by sugars The addition of sugars increases the cariogenicity of cooked starchy foods. Foods containing cooked starch and substantial amounts of sucrose appear to be as cariogenic as similar quantities of sucrose Isomaltooligosaccharides Isomaltooligosaccharides (IMO) contain monosaccharides that are 1-6 linked (but may contain 1-4) IMOs include isomaltose (glucose 1-6 glucose), isomaltulose (glucose 1-6 fructose which is also known as palatinose) and panose (glucose 1-6 glucose 1-4 glucose) IMOs are produced from starch or sucrose by transglucosylation reactions using transglucosylase enzymes Fructooligosaccharides Fructooligosaccharides (FOS) are also resistant to digestion in the upper gastrointestinal tract and increase the growth of bifidobacteria FOS are widely used in the food industry in Japan and increasingly so in the United Kingdom Incubation studies show FOS to be as cariogenic as sucrose, being rapidly metabolized following incubation with several strains of oral streptococci and inducing plaque growth

Human plaque pH studies support these observations indicating FOS to be as acidogenic as sucrose and thus potentially cariogenic Fruit and dental caries Large quantities of grapes and apples have been associated with an increased DMFT, but only in one study Bananas appear to have a greater potential than citrus fruits or apples to cause dental caries, but this does not appear to have occurred in man Fruit juices contain non-milk extrinsic sugars and cannot be considered safe for teeth Based on present evidence, increasing consumption of whole fresh fruit in order to replace non-milk extrinsic sugars (free sugars) in the diet, as recommended by the Department of Health, is likely to decrease the level of dental caries in the population Milk and dental caries Milk is a substantial source of sugars in the diet of young children The sugar in milk is lactose, which is less acidogenic Milk contains phosphorus, calcium, and casein all of which protect against demineralization Animal studies have shown milk to be anticariogenic Human breast milk is higher in lactose and lower in phosphorus and calcium; however, normal breast feeding does not cause dental caries Prolonged, ad libitum, and nocturnal suckling have been associated with increased caries risk Protective factors and dental caries Cows milk is non-cariogenic, since the protective factors present counteract any cariogenic potential due to the lactose content All types of experiment, including a clinical trial, have shown cheese to be cariostatic. Small quantities, that make a negligible contribution to fat intake, are effective Plant foods contain phosphates, which have been shown to be effective at preventing caries in animal studies; but human studies have not produced convincing results A number of foods including cocoa, liquorice, and honey contain protective factors, but their practical potential in reducing caries is limited Foods that are good stimuli to salivary flow protect against dental caries; examples include sugar-free chewing gum, peanuts, and cheese

Intense sweeteners are not chemically related to sugars are added in very small quantities to add sweetness and not volume are hundreds to thousands of times sweeter than sucrose have a negligible energy value (kilocalories) Bulk sweeteners are chemically similar to sugars add volume and sweeteness to a product vary from 0.5 times to 1.0 times as sweet as sucrose have an energy value (kilocalories) many are naturally found in foods

Non-sugars sweeteners The bulk sweeteners sorbitol, mannitol, lactitol, isomalt, lycasin, and maltitol are non-cariogenic or virtually so Xylitol and the intense sweeteners are non-cariogenic Chewing gums sweetened with xylitol and/or sorbitol protect against dental caries. This effect is due to the non-cariogenicity of

the sweeteners and the stimulation of saliva flow resulting from chewing It is important to remember that the usefulness of a sugars substitute has to be looked upon not only from a cariological, but also from a nutritional, toxicological, economic, and technical point of view Effects of sugars intake and fluoride on caries experience Overall, the studies show that when annual sugar consumption is above 15 to 20 kg per person per year, dental caries increases with increasing sugar intake 1520 kg is equivalent to 4155 g per day A number of studies have shown that caries levels increase with intakes of free sugars above four times a day Widespread exposure to fluoride may raise the threshold level of safe intake, and this is reflected in the dietary guidelines adopted by several industrialized countries Recommendations for prevention of dental caries In the presence of adequate exposure to fluoride, the intake of free sugars should be limited to 15 to 20 kg/person per year (equivalent to 40 55 g/day). In the absence of fluoride, the intake of free sugars should be below 15 kg/day (< 40 g/day). These values equate to 610% of energy intake. The frequency of intake of foods containing free sugars should be limited to a maximum of four times a day. The potential financial consequence of failing to prevent dental caries needs to be highlighted, especially to governments of countries that currently have low levels of disease, but are undergoing nutrition transition (adopting a westernized diet). The detrimental impact on quality of life throughout the life coursethe longer-term nutritional consequences of dental caries and tooth lossneed to be highlighted. The myth that a high sugars intake is important for energy intake and growth needs to be dispelled, especially in developing countries where undernutrition is prevalent. Restricting the intake of free sugars to 10% of energy intake would still enable a sustained production of sugar cane as a cash crop in low-income countries. Regular monitoring of the prevalence and severity of dental caries should be encouraged using World Health Organization global guidelines, in different countries in all age groups. More national information on the dietary intake of sugars, sugar availability, and soft drink intake should be collected.

Governments should support research into prevention of dental caries through dietary means. Nutrition needs to be recognized as an essential part of training for dental health professionals, and dental health issues, an important component of education of nutritionist and other health professionals. This is essential if advice for dental health is to be consistent with dietary advice for general health. Departments of Education must ensure that teachers, pupils, and health professionals receive adequate education on diet and dental health issues. There should be crossDepartmental guidelines for the use and content of educational materials to ensure they are sound, and not biased towards the interests of the food industry. International non-govermental organizations (e.g. World Health Organization, Food & Agricultural Organization, FDI, International Association for Dental Research) should recommend fiscal pricing policies for food items that are high in non-milk extrinsic sugars (free sugars) and are otherwise of questionable nutritional value, and should encourage governments to adopt more stringent codes of advertising practice, especially those aimed at children. Food manufacturers should continue to develop and produce low sugars/sugars-free alternatives to products rich in free sugars, including drinks. To enable individuals to make informed choices regarding sugars intake, there is a need for clear, unbiased, and non-misleading labelling of foods with respect to sugars contents. Conclusions This chapter has provided an overview of the evidence for an association between diet and dental caries. For a more comprehensive account, the reader is referred to Rugg-Gunn (1993) and Rugg- Gunn and Nunn (1999). To conclude: collatively, a multiplicity of different types of studies provide convincing evidence of a causal relationship between the amount and frequency of free sugars intake and dental caries. Sugars are necessary for dental caries to occur. Other factors such as exposure to fluoride, oral hygiene practice, and salivary flow rate and composition modify the response to sugars. Fluoride is very effective at reducing dental caries; but it does not eliminate caries, and many low income countries do not have adequate exposure to fluoride. In developed countries where exposure to fluoride is adequate, the only way to further reduce caries is to restrict sugars consumption. Therefore, despite excellent progress made by use of fluoride, sugars restriction remains important in caries prevention in the twenty-first century. The evidence suggests that in order to minimize dental caries, the intake of free sugars should not exceed 1520 kg per person per year.

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (400)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (588)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (895)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (266)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (345)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)

- Ethics AssignmentDokumen18 halamanEthics AssignmentTrina BaruaBelum ada peringkat

- SPM Biology Notes - NutritionDokumen4 halamanSPM Biology Notes - NutritionSPM50% (2)

- Meal Plan For Weight LossDokumen8 halamanMeal Plan For Weight Lossnoorafrin7111Belum ada peringkat

- Efes Distribution CaseDokumen12 halamanEfes Distribution CaseEce Ozcan100% (1)

- Powerpoint DessertDokumen11 halamanPowerpoint DessertDannielle Daphne Cadiogan GasicBelum ada peringkat

- Kvass From Cabbage PickleDokumen11 halamanKvass From Cabbage Picklekkd108Belum ada peringkat

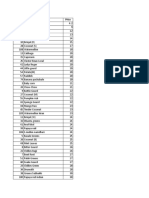

- SL - No Item Name PriceDokumen3 halamanSL - No Item Name PriceAmitKumarBelum ada peringkat

- CuisDokumen5 halamanCuisfaërië.aē chaeBelum ada peringkat

- Texas Roadhouse Rolls - Love Bakes Good CakesDokumen3 halamanTexas Roadhouse Rolls - Love Bakes Good CakesMelissa OviedoBelum ada peringkat

- Creme Brulee Recipe - Alton Brown - Food NetworkDokumen1 halamanCreme Brulee Recipe - Alton Brown - Food NetworkmtlpcguysBelum ada peringkat

- OtherDokumen511 halamanOthernikhil indoreinfolineBelum ada peringkat

- Prevention of Heart DiseaseDokumen43 halamanPrevention of Heart DiseaseamitmokalBelum ada peringkat

- A2 Test Review 456Dokumen8 halamanA2 Test Review 456Minh CTBelum ada peringkat

- Product Innovation:: Tang Powdered JuiceDokumen20 halamanProduct Innovation:: Tang Powdered JuiceSartoriBelum ada peringkat

- Liquid Marijuana Cocktail Recipe - How To Make A Liquid Marijuana Cocktail - Drink Lab Cocktail & Drink RecipesDokumen1 halamanLiquid Marijuana Cocktail Recipe - How To Make A Liquid Marijuana Cocktail - Drink Lab Cocktail & Drink RecipesJazymine WrightBelum ada peringkat

- Jollibee Food Corporation RRLDokumen8 halamanJollibee Food Corporation RRLAui PauBelum ada peringkat

- Sem 1Dokumen112 halamanSem 1Shruti VinyasBelum ada peringkat

- IELTS Reading Section 1Dokumen4 halamanIELTS Reading Section 1Liz ColoBelum ada peringkat

- Punjab Province (Livestock Census 2006)Dokumen157 halamanPunjab Province (Livestock Census 2006)Asim NajamBelum ada peringkat

- 21 Fruits For GlowingDokumen8 halaman21 Fruits For GlowingHoonchyi KohBelum ada peringkat

- Typical Foods of Huila - InglesDokumen6 halamanTypical Foods of Huila - Inglessandra milenaBelum ada peringkat

- Chapter 11 MCDokumen27 halamanChapter 11 MCkenchan0810.kcBelum ada peringkat

- Prokashi BrochureDokumen2 halamanProkashi Brochurestar662Belum ada peringkat

- Operational Guidelines Acute Malnutrition South Africa FINAL-1!8!15-2Dokumen70 halamanOperational Guidelines Acute Malnutrition South Africa FINAL-1!8!15-2RajabSaputra100% (2)

- Skrip Role Play at RestaurantDokumen5 halamanSkrip Role Play at RestaurantDaffa AndiBelum ada peringkat

- SJKC Wu Teck: NameDokumen13 halamanSJKC Wu Teck: NameVivian GraceBelum ada peringkat

- Food MenuDokumen4 halamanFood Menualok kundaliaBelum ada peringkat

- Nutrition and Dietetics Service MID-YEAR UPDATES TEMPLATEDokumen24 halamanNutrition and Dietetics Service MID-YEAR UPDATES TEMPLATEDietary EamcBelum ada peringkat

- Listening Test For Kids-Giaoandethitienganh - InfoDokumen33 halamanListening Test For Kids-Giaoandethitienganh - InfoLê Mỹ Vân VânBelum ada peringkat

- Types of Cakes: Batter Type - Batter-Type Cakes Depend Upon Eggs, Flour and Milk For Structure andDokumen24 halamanTypes of Cakes: Batter Type - Batter-Type Cakes Depend Upon Eggs, Flour and Milk For Structure andRaka Chowdhury100% (1)