Cjasr 12 14 177

Diunggah oleh

Amin MojiriDeskripsi Asli:

Judul Asli

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Cjasr 12 14 177

Diunggah oleh

Amin MojiriHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Caspian Journal of Applied Sciences Research, 1(12), pp.

25-38, 2012

Available online at http://www.cjasr.com

ISSN: 2251-9114, 2012 CJASR

25

Full Length Research Paper

From Strategic Fit to Synergy Evaluation in M&A Deals

Arabella Mocciaro Li Destri, Pasquale Massimo Picone*, Anna Min

University of Palermo University of Catania University of Catania, Italy

*Corresponding Author: pmpicone@gmail.com

Received 15 September 2012; Accepted 18 October 2012

The aim of this paper is to grasp the processes underlying the genesis and assessment of synergies in M&A deals.

We proceed to an in-depth scrutiny of the foundations of synergies using Porters model of the value chain. A

discernment of the nature of synergies and the mode of their emergence is helpful to clarify to what extent and

under which boundary conditions it is appropriate to apply the DCF or the real option techniques for evaluating

each type of synergy. Combining both financial tools, the methodology suggested for evaluating the synergies is

able to: evaluate projects of M&As, orient the selection of target firms and the definition of the premium of

acquisition, and drive the integration processes.

Key words: merger, acquisition, synergy, Porters value chain, evaluation.

1. INTRODUCTION

In recent decades, M&A research in managerial

literature and corporate finance studies has

developed rapidly. These advances include a

handful of ideas about the nature, antecedents, and

economic and financial impact of business

combinations (Meglio and Capasso, 2012).

However, the debate about the shareholder value

creation of businesses combinations has resulted in

partial and inconsistent conclusions (Haleblian et

al., 2009). Mapping the main studies,

institutionalized streams, and dominant theoretical

explanations, Ismail et al. (2011) concluded that

research on the effect of M&A on abnormal returns

for both acquiring and acquired firms is

inconclusive (Tse and Soufani, 2001; Andre, Kooli

and LHer, 2004; Choi and Russell, 2004;

Megginson et al., 2004; Yook, 2004); similarly,

studies that use accounting-based measures show

contradictory positions (Ghosh, 2002; Heron and

Lie, 2002; Ramaswamy and Waegelein, 2003). In

addition, King et al. (2004) indicated that

unidentified variables may explain the significant

variance in post-acquisition performance.

Moreover et al. (2008) found a path linking

integration process performance to long-term firm

results via synergy achievement.

In approaching the topic of M&A performance,

Sirower (1997) argued that the key to

understanding the dynamics underlying the

performance of M&A is the comparison between

the amount of premium of acquisition (that is

negotiated between the parties) and the value of

synergies that a business combination generates.

The choice to acquire a firm or merge with

another firm should result from a well-developed

corporate strategy (Payne, 1987). Conversely, the

lack of understanding of the nature and sources of

synergies and their appropriate evaluation results

in exceeding the reservation price and leads to the

synergy trap (Sirower, 1997) i.e., a downward

spiral that involves the progressive and incremental

destruction of wealth. More in detail, the

mechanisms underlying the synergy trap are (a)

the improper transfer of resources from

stockholders of the acquiring firm to shareholders

of the target, (b) increase in risk-seeking behavior

and baring-risk by management and the pressure to

recover from poor performance following the

completion of the transaction, and (c) the negative

effects and costs associated with drainage of

financial resources that are vital to supporting the

initial integration processes and operational

strategic business combinations.

Taking into account that the acquisition

premium plays a key role in M&A performance

(Sirower, 1997; Krishnan et al., 2007), and

continuous need of practitioners to obtain results

that can be helpful to manage M&A processes

(Very, 2011), the object of this paper is to discern

the main variables that are instrumental in creating

or destroying value in M&A deals in the process of

synergy evaluation. First, we examine the

procedural aspects - operational, functional,

organizational, and strategic - that are the basis of

Mocciaro Li Destri et al.

From Strategic Fit to Synergy Evaluation in M&A Deals

26

value creation in M&A deals. Successively, we

categorize the various sources of synergy and how

best to evaluate each of them. Therefore, we

develop a methodology to assess the synergy value

that is the result of a path of research that lies at the

intersection of strategic management and corporate

finance. We address the need to integrate valuation

tools from corporate finance and principles from

the fields of strategic management to better

understand value creation in financial markets

(Smit and Trigeorgis, 2004; Sirower and Sahni,

2006).

This paper is organized as follows. Section two

aims to clarify the concept of synergy. In section

three, using Porters value chain as a conceptual

support, we conduct a detailed investigation of the

sources of synergies in the operations of M&A. In

section four, we classify the various sources of

synergies previously identified on the basis of the

degree of predictability. We then discuss the

scheme guide in the choice of valuation techniques

for each class of synergies. In section five, we

present synthetic formulas for evaluating synergies

in M&A. Section six offers conclusions,

underscoring the problem of the appropriation of

synergy value.

2. CONCEPTUAL DEVELOPMENT

The term synergy comes from the Greek word

synerga or synrgeia; in turn, this word is derived

from synergo. From an etymological perspective,

the roots of the word synergy are syn (with,

together) and ergo (act). Synergy concerns the

results of different factors taken together versus a

sum of the factors.

From an etymological point of view, the

concept of synergy possesses a neutral meaning:

the joint effect of two or more factors is different

from their simple sum. Consequently, the synergy

value may be positive, if a combination of factors

improves the effectiveness of actions alone, or

negative, if the result of joint action of two or more

factors is less than their simple sum.

Generally, the justification of M&A operations

is the intention to create positive synergies. It

means that the value of the business combination is

assumed expected to be greater than the value of

the two firms considered independently:

[1]

B A AB

W W W + > ,

[2] S W W W

B A AB

+ + = ,

where W

AB

is the value of business

combination, W

A

and W

B

are respectively the

values of firms A and B, and S is the value of the

synergies emerging from the combination.

However, as already mentioned, the empirical

studies regarding the results of M&A operations

show high variability (Hitt et al., 2001); therefore,

it is also important to consider the possibility that

negative synergies emerge.

[3]

B A AB

W W W + < ,

[4] S W W W

B A AB

+ = .

Only detailed strategic planning and hardnosed

economic assessment of the costs and benefits

entitled by post-acquisition operational processes

can provide the necessary basis for a rational

estimate of the potential synergies entailed by

specific M&A operations. This evaluation,

therefore, entails the integration of perspectives

and techniques from the field of both strategy and

finance. It needs bringing strategy back into

financial systems of measurement (Mocciaro Li

Destri et al., 2012). Essentially, the generation of

synergies is linked with corporate growth,

increased market power, and greater profitability

(Alexandridis et al., 2010). Therefore, the

assessment of synergies implies estimating the

strategic fit (Shelton, 1988), and, successively,

shareholders value creation. Actually, paying a

high acquisition premium is often a measure of

low-quality decision making (Laamanen, 2007).

The breakings down of the acquisition value

and of the synergy value have been analyzed in the

finance literature (Massari, 1998; Zanetti, 2000).

On the basis of Massari and Zanetti's models, the

formulation of a measurement method should

include three types of synergies. The first type,

incremental cash flow synergies (S

F

), concerns the

cash flows that the business combination generates

according to a plan of integration. The second type

of synergies is related to flexibility. The real

options synergies (S

O

) concern how the business

combination increases the firms capability to

respond to the evolution of the competitive

environment. Actually, real options analysis has

progressively emerged as a pivotal methodology to

assess investment opportunities when the

environments are characterized by high levels of

uncertainty (Dixit and Pindyck, 1994). This

synergy, thus, aims to capture the flexibility value

resulting from the firms adaptive capabilities

(Smit and Trigeorgis, 2004). Finally, the third type

of synergies regards the change of the firms risk

profile (S

R

) as a result of the operation of M&A.

Moving from the conceptual break-down of the

notion of synergies in M&A operations, it becomes

apparent those in order to aid managerial

evaluations there is the necessity and classify the

Caspian Journal of Applied Sciences Research, 1(12), pp. 25-38, 2012

27

sources of different classes of synergies and,

further, elaborate specific evaluation techniques for

each class of synergies.

In synthetic terms, the equity value of the

synergies will be calculated as follows:

[5]

R O F

S S S S + + = .

Therefore, the estimated value of a business

combination - assuming the DCF in asset

perspective - ideally consists of the following

elements:

[6]

AB R O F B

B

A

A

AB

D S S S )] D W ( ) D W [( W + + + + = .

Where:

-

A

W e D

A

represent the value of the assets

and the value of debt for the firm A;

-

B

W e D

B

represent the value of the assets

and the value of debt for the firm B;

-

F

S ,

O

S e

R

S indicate the estimated value

of synergies classified as above; and

-

AB

D A Indicates the change in value of

total debt.

Simplistically, we can rewrite the [6]

formula as:

[7] ) D D (D ) S S S ( ) W W ( W

AB B A R O F

B A

AB

+ + + + + + =

.

The formula [7] asks an effort to categorize the

synergies in

F

S ,

O

S e

R

S on the basis of the nature

and the mode to emerge of them.

3. THE GENESIS OF SYNERGIES IN M&A

OPERATIONS

In this section, we identify the various sources of

potential synergies in M&A operations. Using

Porter's model of the value chain (Porter, 1985) as

a conceptual support to investigate the processes of

structural integration between firms, we analyze

the operational and strategic impact of M&A deals.

By following this practice, we aim to give a

twofold contribution. On one hand, we underscore

the integration priorities that should precisely

match the value and type of synergies that drove

the deal in the first place (Ficery et al., 2007). In

this perspective, the aim of the analysis is to find

profit-making opportunities (Bruner, 2004).

Actually, our analysis shows the foundations of

sustained competitive advantages generated by

potential synergies (Gruca, Nath and Mehara,

1997). On the other hand, for each of the identified

sources of synergy, we discuss its nature in order

to support the subsequent of synergy evaluation.

Fig. 1: Conceptual scheme for identifying potential synergies in M&A deals (Payne, 1987)

Firm infrastructure

Technology development

Human Resource Management

Procurement

Service Marketing

& Sales

Outbound

logistics

Operations Inbound

logistics

Margin

Technology development

Firm infrastructure

Human Resource Management

Procurement

Service Marketing

& Sales

Outbound

logistics

Operations Inbound

logistics

Margin

Overall

potential

Potential

Potential

Potential Potential

Potential

Potential

Mocciaro Li Destri et al.

From Strategic Fit to Synergy Evaluation in M&A Deals

28

3.1. Synergies Generated in the Procurement

and Logistics Functions

The first class of synergies arising from the

functions in question concerns the reduction of

transaction costs generated by the upstream

integration of production of one or more inputs.

The choices of make or buy (Williamson, 1971;

Perry, 1989; Grant, 1996) not only depend on the

cost of buying the goods, but also on the costs of

research and selection of the suppliers, the costs of

negotiating contract terms, the costs of sending

orders, controlling cost, the costs of the receipt of

materials, the cost of controlling the quality of

goods, administrative costs and, the costs of the

settlement of payments.

Moreover, vertical integration can generate

synergies in the supply of technological goods.

Perry (1989) underscored that interdependence

between phases of the supply chain can reduce the

use of some production inputs.

In addition, synergies can be achieved as a

stochastic increasing return in the management of

raw materials. Unit costs of maintenance of raw

materials, namely those generated by retention and

storage of goods (financial charges, insurance

charges, storage charges resulting from the risks,

expenses and charges related to the additional

space handling) are almost identical ex ante and ex

post merger or acquisition. However, the optimal

quantities of raw materials stored in warehouses to

minimize the risk of running out of stock cost, in

the case of homogeneity of raw materials between

firms, it can be reduced for the effect of stochastic

increasing returns (law of large number).

The last type of potential synergies related to

procurement stem from the increase in bargaining

power with suppliers. Often, the business

combination reduces the number of buyers, raises

the volume bought and, therefore, poses the basis

for the reduction of procurement costs. The

emergence of these synergies should not be taken

for granted in every operation of M&A and for

each supplier; in fact, it is important that we reach

a critical size to gain significant bargaining power.

We need to estimate the probability of obtaining

favorable terms and the amount of benefits that

suppliers may grant.

3.2. Synergies Generated in the Production

Function

M&As can generate synergies related to increased

efficiency thanks to the new dimension reached by

the business combination. First of all, horizontal

M&As - i.e., between firms operating in the same

industry may consent the rationalization of the

production process, reaching a production capacity

that is optimal given industry dynamics and

technical aspects (such as the efficient use of

establishments or the minimum efficient scale)

(Capron, 1999).

A second class of potential synergies related to

the production function includes all sources of

economies of scale (Scherer, 1980; Gold, 1981;

Hill, 1988). Achieving economies of scale plays a

very important theoretical justification in M&As,

because they generate strong differences in

competitiveness between firms. Economies of

scale arise when the return of the production

function increases with the size of the production

plant (Collis and Montgomery, 1997). The

emergences of economies of scale imply a

reduction of average unitary production costs when

production increases (Lambrecht, 2004). Possible

sources of the basic achievements of economies of

scale (Zattoni, 2000) are:

a. the geometrical properties of some plants.

Cash flows generated from this synergy are

estimated with reasonable objectivity (i.e., flows

on the basis of differential) by technicians and

production engineers;

b. indivisibility of some inputs. M&As may

help balance the production line. Bringing the flow

of production to a level equal to the lowest

common multiple of the capacity of each machine.

The cash flows generated by this class of synergies

are also simple to estimate for technicians and

production engineers. In addition, when it is

possible to dismiss one or more plants, it is

appropriate to evaluate the flow of revenues

resulting from their sale;

c. stochastic increasing returns in the

management of stocks (finished and semi-

finished). These synergies are due to the fact that,

the amount of inventory with unforeseen needs is

less than the sum of stocks that firms previously

kept in their stores; and

d. similar considerations concern the reduction

of reserve capacity for the case of an unpredicted

increase of the number of customers served. In this

case, the evaluation needs to take into account

maintenance costs (operational and financial) of

spare capacity multiplied by the reduction of spare

capacity;

e. in theory, the synergies include the increase

of the statistical regularity that allows a more

efficient use of larger plants. Generally, however,

this impact is unimportant.

The last class of synergies regards the scope

Caspian Journal of Applied Sciences Research, 1(12), pp. 25-38, 2012

29

economies connected to the production function,

the value of which is relevant in the operations of

related diversification. Similarly to scale

economies, they generate cost saving flows.

3.3. Synergies Generated in the Marketing

Function

Firms may implement M&As in order to realize a

strategy of market domination and to create new

competitive conditions. Actually, M&A is an

efficacy tool to rapidly expand market share in an

industry. In this regard, however, it seems

appropriate to underscore synergies related to

reduction of competitive pressure are, taken on

their own, often insufficient to make the operation

of M&A profitable. In fact, Salant et al. (1983)

showed that, in absence of other synergies, the

horizontal merger between firms that use a game

scheme la Cournot is not profitable for the

business combination, while it creates benefits for

the remaining outside firms (the exceptions are

cases in which M&A deals involve almost all firms

originally active in the market).

The synergies resulting from the increased

market power stem from:

- the possibility of raising prices; and

- the reduction of marketing costs due to the

decrease in competition.

However, M&A deals are often intended as a

tool to defend the competitive position achieved. In

this case, the M&A aims to eliminate a firm,

although it is not a direct competitor, in order to

preempt it from launching an aggressive strategy in

the future. In this case, the evaluation of synergies

considers the differential increased cost in

advertising or reduction in product prices under the

hypothesis that the M&A had not been conducted.

When an M&A extends the business portfolio

and the scope economies of marketing, these

synergies can play an important role in

determining the operations performance. The

concept is very close to the above-mentioned

economies of scale applied to the production

function. Often, to ensure the development of the

firm, it may need to add different categories of

products to its portfolio, thus extending its product

range. In this sense, M&A operations may

represent a vehicle to grasp the strategic option of

entering a related market and, simultaneously,

exploiting the advantages of brand loyalty through

brand extension. Obviously, these synergies are

even more significant when the acquired firm is

anonymous, but operationally sufficiently

complete (Roedder and Loken, 1993). In addition

to brand scope economies, brand extension

strategies may enhance the brand equity of origin.

Often this strategy clarifies, strengthens, or widens

the scope of the brand of origin, increasing market

coverage, and revitalizing the sales of the brand

(Keller, 2003).

However, the extension of the brand into

another market can have negative effects for two

reasons. First, it may create confusion in consumer

preferences. Second, products made by the

acquired (or merged) firm may fail to satisfy a

quality level traditionally connected to the brand.

In such cases, the brand extension may generate a

negative effect on the image of the parent brand

(Reddy et al., 1994; Martinez and Pina, 2003;

Zimmer and Bhat, 2004).

If the synergies emerging from process of brand

extension are considered to derive from the

M&As value, then it must be considered as an

investment with a highly uncertain probability of

effective realization. Conversely, if the effects of

the brand extension are only a reduction in

communication costs, synergies can be evaluated

in terms of investment flows by considering their

differential levels.

In addition, the marketing function can generate

synergies in relation to the development of

multiple brands. Multiple brand strategy allows

companies to obtain more display space and

greater negotiation power with distribution firm.

These benefits should be carefully scrutinized, as

excessive use of multiple brands sparking off a

process of cannibalization between brands. In

this case, the business combination dissipates its

resources through a many-brand-sided

development, rather than focusing on a few brands

with high levels of profitability (Kotler, 1992).

Marketing synergies can also be connected to

sharing retail networks. M&As may consent the

access of new distribution channels (Mocciaro Li

Destri and Min, 2009, 2010), thus allowing to

reach different customer segments, or overcome

barriers to entry in certain markets.

Finally, synergies related to the marketing

function may emerge from the rationalization of

the marking workforce. These synergies are typical

in M&As that aim to expand the geographic

extension of the business portfolio. Divisions of

the new business combination that overlap in one

area, lead to the reduction of costs through the

elimination of duplicate facilities and personnel

redundancies.

Mocciaro Li Destri et al.

From Strategic Fit to Synergy Evaluation in M&A Deals

28

3.4. Synergies Generated in the Organization

Function

The integration of structures of the business

combination should ensure a desirable level of

both autonomy and coordination to the different

divisions. It is necessary to make decisions about

how to distribute authority positions within the

renewed organization, redesigning new tasks and

projects, including temporary teams. Human

resource management will focus first on

identifying workers who will remain part of the

business combination and, eventually on new

training. The organizational synergies amount to

the savings cost generated by fining redundant.

During the initial period, however, the net

investment required for the preparation of

organizational conditions for harmonization of

technical aspects must be consider.

Dismissal policies need particular attention.

The rationalization of corporate structures involves

both workers at the lower and middle level of the

organizational pyramid. In fact, sharing technical,

administrative and support activities often implies

making a part of the employees, redundant (or

relocating them). Finally, restructuring human

resources also involves middle and top

management. Often, a significant part of them are

excluded from new structures of corporate

governance. The policies of workers dismissal are

generate uncertainty and stress in human resources.

Under these conditions, they tend to reduce their

levels of activity and productivity.

Last but not least, we underscore that excessive

growth in size leads to phenomena of free-riding:

Each worker is potentially less controllable, and

this might be an incentive to contribute less than

required. In fact, when the span of control

increases, there is the need to create several

hierarchical levels that can however increase both

the costs and the level of rigidity of the

organizational structure.

3.5. Synergies Generated in the R&D Function

Before introducing the analysis of the synergies

that may emerge in R&D function, it is useful to

point out that although the operations of M&A are

a tool to enhance the capacity to access patented

innovations, the performance of this process does

not constitute a synergy. Actually, the same value

creation effect could be obtained simply by

licensing patent (namely, accessing the knowledge

patented through licenses).

The first class of synergies in the R&D function

stems from reaching a size which is critical in

order to join a network of firms, as complex

dynamic systems of knowledge and capabilities

(Dagnino et al., 2008), considered effective in

terms of innovation. The importance of such

relationships for the conquest and defense of

competitive advantages is related to the integration

of complementary skills between different firms

(for instance, Saxenian, 1994; Powell et al., 1996;

Basile, 2012). Synergies arise from the entrance in

a network of real options with low exercise

probability, the value of which depends on their

contribution to the network in generating

innovation, the probability of technological

success, and the likelihood of commercial success.

The actual realization of synergies related to

entering a new network is largely uncertain.

However, we underscore that information is the

critical resource that generates strategic flexibility

to recognize and capture project values hidden in

dynamic uncertainties. Actually, since information

is a critical resource in uncertain environments, the

main benefit of entry into a new network through

M&A deals is that it provides a platform for future

strategies.

The second class of synergies in R&D - fairly

common in M&A operations aimed at filling

technology gaps - is achieved through learning and

developing new technologies (Link, 1988; Capasso

and Meglio, 2005; Graebner et al., 2010). Makri,

Hitt and Lane (2010) find that similarities between

firms in knowledge facilitate incremental renewal,

while complementarities would make

discontinuous strategic transformations more

likely. Nonetheless, M&A may shape new

capabilities by integrating existing and new

resources that were previously unrelated; the

phenomena tend to have a high impact when the

M&A implements a related diversification

strategy. In fact, according to Finkelstein and

Haleblian (2002), routines and practices developed

in one firm transfer to other firms through business

combination operations on the basis of the degree

of similarity of industrial environments from which

they proven. However, organizational learning

thought M&A deals is extremely difficult

(Barkema and Schijven, 2008; Hitt et al., 2009)

vis--vis alliances (Dagnino et al., 2012).

This second class of synergies is typical of

M&As between large firms and small firms, in

which the big corporation has considerable

commercial and productive resources focused on

marginal innovations. Conversely, the small firm is

really innovative. In this perspective, M&As may

30

Caspian Journal of Applied Sciences Research, 1(12), pp. 25-38, 2012

29

play a role in reducing the time to generate an

innovation and the appropriation of value from it

(Mocciaro Li Destri and Dagnino, 2012)

The appreciation of the R&D synergies is

extremely complex (especially in international

M&A). In fact, the level of technological

knowledge gained by the two firms separately

results partly from the ability to absorb knowledge

from outside and partly from internal R&D, so

appreciation of the technological quality of

synergies as the fundamental driver of value

creation in M&A should be assessed in

relationship to the possibility of recombination of

knowledge and technology (Bresman et al., 1999).

Finally, a complex synergy to gain is the

possibility that M&A deals can increase invention

in new areas. M&As may foster the generation of

future choices and potential for proprietary access

to outcomes (McGrath et al., 2004). This

hypothesis underscores that operating in distant

markets increases a firms knowledge of its

resources various possible utilizations, thereby

generating new expansions possibilities. In this

perspective, M&A deals are a way to create new

possibilities for future efficiency. It supports the

capacity to learn how to alter the resource

configuration in adaptation to market changes. In

this case, the uncertainties underlying the estimate

of potential synergies increase significantly,

making it crucial to use precautionary criteria of

estimation. Precautionary criteria have also to

consider that, generally, M&A have a positive

effect on patenting output, but decrease patent

impact, originality, and generality (Valentini,

2012).

3.6 Synergies Generated in the Financial

Function

Since combinations of firms can improve the risk

profile of business combinations, the finance

function is a source of synergies in M&A deals. In

an M&A context, the variables that reduce the

level of risk connected to the firm are the larger

size of the resulting corporation firm and, possibly,

higher degree of diversification. Conversely, risk

increases whenever operating and financial

leverage ratios increase rending the firm more rigid

(Schweitzer et al., 1992). It is important to

understand if reductions in the risk factors are

offset (or more than offset) by increases in firm

financial or operational rigidity.

Since a conglomerates corporate office can

allow for a higher level of indebtedness (Lewellen,

1971; Picone, 2012) and advantages of

deductibility interests, a lower cost of debt capital

may emerge as result of M&A operation.

In the case of acquisitions, it is also important

for the estimation of the WACC to consider a

discount associated with the obstruction in the

deliberative assemblies that minority shareholders

could implement if they are excluded from any of

the benefits available to majority shareholders.

4. THE NATURE OF SYNERGIES

In the preceding section, we identified the sources

of synergies, using Porter value chain to map

them function by function. Moving from these

findings, we can classify potential synergies on the

basis of their nature and, in particular, their mode

of emergence. Following the classification

illustrated above, there are three types of synergies:

- the value of incremental cash flow synergies

that M&A deals generate (S

F

);

- the value of the real options synergies that

M&A deals generate (S

O

); and

- the value determined by changes in the firms

risk profile as a result of M&A (S

R

).

Regarding the classification of synergies

between differential flows or real options, we find

a criterion in the distinction between tangible and

intangible resources and the degree of innovation

entailed by the integration process. The emergence

of synergies from material resources, under the

organizational and technological compatibility,

through the generation of cash flow is relatively

straight forward to asses. In contrast, the

emergence of synergies regarding intangible

resources can be highly uncertain. Accordingly, in

the first case, the synergy benefits should be

evaluated by discounting the cash flows at a rate

whose level reflects the risk profile associated with

the businesses combination. In the second case, it

is better to refer to the option pricing models

developed by modern financial theory, since they

take into account the higher profile of uncertainty

to which this type of synergies is subject. In this

case, the discounted cash flow approach in itself

is insufficient and therefore, the options framework

is a valuable tool-kit not only for analysts but also

for the decision-makers in the top management of

the firm (Krishnamurti and Vishwanath, 2008:

139). Real option synergies underscore that an

M&A deal may create economic value using the

combination of scarce resources to undertake a

potential opportunity in the environment

(Andrews, 1971; Chatterjee, 1986). However, the

evaluation of these synergies makes sense only if

31

Mocciaro Li Destri et al.

From Strategic Fit to Synergy Evaluation in M&A Deals

28

in the future there the conditions for their

realization exists or at least is likely to be fulfilled.

Finally, the synergies determined by changes in

the corporations risk profile as a result of the

M&A (S

R

) and computed according to the rules of

finance should be considered in the definition of

the WACC discount rate. This practice is

consistent with the nature of S

R

(i.e. the risk of a

quality variable); consequently, it is estimated

indirectly.

Table 1: Matrix of the main synergies

Market power Sharing tangible resources Sharing intangible resources

- increased bargaining power

toward suppliers

- increased bargaining power

toward commercial distribution

- increased bargaining power

toward customers

- rationalization of corporate

structure (production and

administration)

- reduction of vertical integration

costs

- technological economies

- reduction of inventories

- economies of plant

- economies of scale

- economies of scope

Low degree of innovation

- economies of scale for marketing

function

- streamlining the sales network

High degree of innovation

- mode of access to new distribution

channels

- mode of entry into innovative

networks

- mode of learning technology

- invention of new sectors

- developing markets in poorly

staffed and brand extension

strategy

New risk profile (S

R

)

5. A MODEL OF SYNERGIES ASSESSMENT

IN M&A DEALS

The previous section offered a categorization of

the sources of synergy and how to assess them.

Obviously, the total value of the synergies in an

M&A operation is the result of their sum. In

particular, we have designed a method that

considers jointly the DCF techniques - to measure

S

F

and S

R

- and the Real Option technique - to

evaluate S

O

. The two approaches of financial

theory allow us to add values determined

separately, because they share the same heuristic

purpose, which is to summarize the potential value

of the complex results from a combination of

firms.

The methodology assumes the asset

perspective, considering the WACC rate

adjustment for the effects of debt (which we call

WACC**). We justify this choice because of the

need for agility, speed, and synthesis for the

selection of the target firm.

In this section, we focus our attention on the

addition of formula [7]. Indicates the change in

value of total debt.

Simplistically, we can rewrite the [6]

formula as:

[7]

) D D (D ) S S S ( ) W W ( W

AB B A R O F

B A

AB

+ + + + + + =

,

5.1 Estimating the Incremental Cash Flows

S

F

S

O

S

F

S

F

32

Caspian Journal of Applied Sciences Research, 1(12), pp. 25-38, 2012

33

The strategic plan of an M&A operation should

explain how the resources and skills will be

recombined to obtain market rents or economies in

costs. We distinguish between post-acquisition

synergies (or immediate), which are the result of

the new asset allocation (for example, the sale of a

plant unnecessarily duplicated as a result of the

operation of M&A), synergies achievable within

the time horizon of the plan, for which it is

possible to elaborate analytical predictions; and

potential synergies beyond the term of the plan. It

is not possible to analytically estimate the better

synergies; rather they can be estimated only on

average.

The value of incremental cash flows may be

calculated as follows:

[8]

* *

t * *

AB

t

1 i

i * *

AB i

F

WACC

) WACC )(1 (FCFO

) WACC (1

) (FCFO

S

=

+

+

+

=

,

where (FCFO

iAB

) indicates the differential

operating cash flow of the businesses combination

estimated analytically; (FCFO

AB

) indicates the

average differential operating cash flow of the

businesses combination from the time t on; and

WACC** represents the weighted average cost of

capital of the businesses combination.

5.2 Estimating Real Options Synergies

As illustrated earlier, M&A operations may create

value by enhancing the degree of fine flexibility

and adaptability to external changes. Given the

uncertainty connected to these synergies, the DCF

evaluation method is inappropriate. However, real

option theory is able to evaluate the business

combinations capacity to identify major changes

in the external environment, quickly commit

resources to new courses of action in response to

those changes, and recognize and act promptly

when it is time to halt or reverse existing resource

commitments (Shimizu and Hitt, 2004). Using the

formula proposed by Black-Scholes model

adjusted for dividends, the value of a real option is

given by:

[9] ) N(d Ke ) N(d Se O

2

rt

1

yt

= .

where S is the present value of the potential

development project; K is the initial investment

necessary for the development of the project; R

indicates the risk-free interest rate corresponding to

the duration of the option; T is the time to

expiration in years; Y indicates the instantaneous

rate of dividend; and N (d

1

) and N (d

2

) are

functions corresponding to the cumulative normal

distribution to standard normal variables,

respectively:

t

t

2

y - r

K

S

ln

d

2

1

|

|

.

|

\

|

+ + |

.

|

\

|

= e t d d

1 2

= ;

where

2

is the variance of the natural logarithm

of the value of the underlying asset.

It is important to stress that several problems

may arise. The first is the difficulty of estimating

all variables of the new investment and their

capability to generate cash flow. Second, the

evaluation of real options requires a cautious

approach. The evaluation is justified by the

possibility of creating sustainable competitive

advantages in the long run. If the process of

evaluation is repeated for all p flexibility options

that the operation of M&A generates, we have the

value of S

O

.

[10] | |

= =

= =

p

1 h

p

1 h

h 2

rt

1

yt

h O

) N(d Ke ) N(d Se O S .

5.3 Estimating the Synergies that Emerge from

a Different Risk Profile

Finally, we must proceed to estimate the synergies

that arise from the different risk profiles. We

compare the value of firms under the assumption

of unity of the economic entity (businesses

combination) and the value of firms under

situations of managerial independence (as before

the extraordinary operation), i.e., standalone firms.

Mocciaro Li Destri et al.

From Strategic Fit to Synergy Evaluation in M&A Deals

34

We can formalize the evaluation of synergies that emerge from a different risk profile as follows:

[11]

. D

WACC

) WACC )(1 (FCFO

) WACC (1

) (FCFO

D

WACC

) WACC )(1 (FCFO

) WACC (1

) (FCFO

D D

WACC

) WACC )(1 FCFO (FCFO

) WACC (1

) FCFO (FCFO

S

B

* *

B

t * *

B B

t

1 i

i * *

B

iB

A

* *

A

t * *

A A

t

1 i

i * *

A

iA

B A

* *

t * *

B A

t

1 i

i * *

iB iA

R

+

+

+

+

+

+

+ +

+

+

+

=

where FCFO

iA

, FCFO

iB

are respectively the

operating cash flows of firm A and firm B in year

i; FCFO

A

, FCFO

B

are respectively the average

operating cash flow of the firm A and the firm B

from t on; and D

A

and D

B

are the economic value

of the debts of the firm A and of the firm B.

The WACC of A and B before the M&A

transaction is adjusted on the basis of the

procedure in order to keep the tax benefits of debt

into account.

Simplifying the above expression, we have:

[12]

.

WACC

) WACC )(1 (FCFO

) WACC (1

) (FCFO

WACC

) WACC )(1 (FCFO

) WACC (1

) (FCFO

WACC

) WACC )(1 FCFO (FCFO

) WACC (1

) FCFO (FCFO

S

* *

B

t * *

B B

t

1 i

i * *

B

iB

* *

A

t * *

A A

t

1 i

i * *

A

iA

* *

t * *

B A

t

1 i

i * *

iB iA

R

+

+

+

+

+

+

+ +

+

+

+

=

Estimating the Total Value of Synergy (S

F

)

To find a synthesis of all the expressions obtained, we proceed to combine [7], [8], [10] and [12]:

[13]

| |

. D

WACC

) WACC )(1 (FCFO

) WACC (1

) (FCFO

WACC

) WACC )(1 (FCFO

) WACC (1

) (FCFO

WACC

) WACC )(1 FCFO (FCFO

) WACC (1

) FCFO (FCFO

) N(d Ke ) N(d Se

WACC

) WACC )(1 (FCFO

) WACC (1

) (FCFO

S

AB

* *

B

t * *

B B

t

1 i

i * *

B

iB

* *

A

t * *

A A

t

1 i

i * *

A

iA

* *

t * *

B A

t

1 i

i * *

iB iA

p

1 h

h 2

rt

1

yt

* *

t * *

AB

t

1 i

i * *

AB i

+

+

+

+

+

+

+ +

+

+

+

+

+ +

+

+

+

+

=

=

=

From this formula, we derive the following compact formula:

[14]

| | . D ) N(d Ke ) N(d Se

WACC

) WACC )(1 (FCFO

) WACC (1

) (FCFO

WACC

) WACC )(1 (FCFO

) WACC (1

) (FCFO

WACC

) WACC )(1 (FCFO

) WACC (1

) (FCFO

S

p

1 h

AB h 2

rt

1

yt

* *

B

t * *

B B

t

1 i

i * *

B

iB

* *

A

t * *

A A

t

1 i

i * *

A

iA

* *

t * *

AB

t

1 i

i * *

iAB

=

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

=

Caspian Journal of Applied Sciences Research, 1(12), pp. 25-38, 2012

35

6. CONCLUSIONS

This paper offers a systematic analysis of the

sources of the synergies that can emerge in a M&A

deal, mapping function by function and

categorizing the synergies on the basis of their

emergence. Moving from the idea that, if the

strategy is unclear, there is no reason for a firm to

make on M&A deal (Bower, 2001), this analysis

provides the fundamentals for the subsequent

development of a methodology for estimating

different classes of synergies. We make clear the

hidden potential of a generic M&A. A proper

assessment of options for external growth is not

possible without appreciating strategic and

organizational aspects on the basis of the

estimation of the differential cash flows related to

synergies, the impact of M&A on the risk profile

of businesses combination and, finally, without

taking into due consideration the options that the

operation of M&A can generate in terms of

operational and strategic flexibility. The extent of

synergies not included in traditional evaluation

formula is therefore an issue that bridges the gap

between strategy and finance, as it requires a

unified view of phenomena and key operational

processes found in M&A.

The benefits related to a methodology of

assessment of synergies in M&A transactions are

numerous, and extend far beyond the proper

definition of the price fixed through negotiation

between the parties. In particular, these additional

benefits include:

- a template to support the selection of the

target firm (Mitchell and Shaver, 2003). The

measure of potential synergies allows us to

compare different candidate firms. Thus, the

evaluation model proposed may support

management decision-making (Cobblah et al.,

2010);

- a support for the processes of planning and

management of the integration between the firms

(Zollo and Singh, 2004; Schweiger and Lipper,

2005; Dagnino and Pisano, 2008; Teerikangas et

al., 2011) since the value of synergies becomes a

strategic goal and, hence, the instrument to guide

the process of integration between the firms; and

- the definition of a premium of acquisition

consistent with the value of potential synergies, the

payment of the premium (Chang, 1998), and the

management of the financial structure (Lewellen et

al., 1995; Maloney et al., 1993) of the corporations

as a result of the M&A.

This paper gives no specific solutions to a

limited number of aspects of the proposed

methodology for the estimation of synergies,

which may represent areas of interest for further

research on the topic. More research needs to be

done to examine on methods - qualitative and

quantitative information to accurate the

estimation of the unlevered cost of equity of the

combining firms. In this perspective, we recall also

the need to develop rigorous algorithms for

correction of the rate to discount cash flows to

consider tax benefits, the costs of (so-called)

financial stress, and control costs.

Finally, the applicability of financial options

techniques asks new investigations on applicable

principles of option pricing theory in real contexts.

While Black-Scholes formula is appropriate to

assess the value of a financial investments, the

application of Black-Scholes formula in real

context violates some theoretical assumptions, e.g.

the lognormal distribution of the project values. On

the other hand, empirical estimation of the inputs

in Black-Scholes formula is really complex, for

example the volatility is not easy to estimate.

REFERENCES

Alexandridis G, Petmezas D, Travlos NG (2010).

Gains from Mergers and Acquisitions

Around the World: New Evidence. Financial

Management Journal, 39(4): 1671-1695.

Andre P, Kooli M, LHer J (2004). The Long-Run

Performance of Mergers and Acquisitions:

Evidence from the Canadian Stock Market.

Financial Management, 33(4): 27-43.

Andrews KR (1971). The Concept of Corporate

Strategy, Dow-Jones-Irwin, Homewood, III.

Barkema HG, Schijven M (2008). How do firms

learn to make acquisitions? A review of past

research and an agenda for the future.

Journal of Management, 34(3): 594-634.

Basile A (2012). Evaluating R&D Networking to

Revitalize SMEs Innovative Performances: a

Management Perspective. Business: Theory

and Practice, 13(3): 217-227.

Bower J (2001). Not all M&As Are Alike and

That Matters, Harvard Business Review,

79(3): 92-101.

Bresman H, Birkinshaw J, Nobel R (1999).

Knowledge transfer in international

acquisitions. Journal of International

Business Studies, 30(3): 439-462.

Bruner R (2004). Applied Mergers and

Acquisitions. John Wiley & Sons, New

York.

Capasso A, Meglio O (2005). Knowledge transfer

in mergers and acquisitions: how frequent

Mocciaro Li Destri et al.

From Strategic Fit to Synergy Evaluation in M&A Deals

36

acquirers learn to manage the integration

process. In Capasso A, Dagnino GB, Lanza

A (2005). Strategic Capabilities And

Knowledge Transfer Within And Between

Organizations: New Perspectives from

Acquisitions, Networks, Learning And

Evolution Edward Elgar Publishing, 199-225

Capron L (1999). The Long-Term Performance of

Horizontal Acquisitions. Strategic

Management Journal, 20(11): 9871018.

Chang S. (1998). Takeovers of Privately Held

Targets, Methods of Payment, and Bidder

Returns. Journal of Finance, 53(2): 773-84.

Chatterjee S (1986). Types of Synergy and

Economic Value: The Impact of Acquisitions

on Merging and Rival Firms. Strategic

Management Journal, 7(2): 119-139.

Choi J, Russell J (2004). Economic Gains around

Mergers and Acquisitions in the Construction

Industry of the United States of America.

Canadian Journal of Civil Engineering,

31(3): 513- 525.

Cobblah M, Graham M, Yawson A (2010). Due

diligence on strategic fit and integration

issues: A focal point of M&A success. In

Gleich IR, Kierans G, Hasselbach T (eds.)

Value in Due Diligence, Gower Publishing

Ltd, Surrey, England. UK, 3-15.

Collis DJ, Montgomery CA (1997). Corporate

Strategy: Resources and the Scope of the

Firm, Irwin, Chicago.

Dagnino GB, Filippas V, Mocciaro Li Destri A,

Rocco E (2012). Le alleanze strategiche quali

percorsi di creazione di valore: unindagine

qualitativa sulle alliance evolution

capabilities. Finanza Marketing e

Produzione, 1: 93-139.

Dagnino GB, Levanti G, Mocciaro Li Destri A

(2008). Evolutionary Dynamics of Inter-firm

Networks: A Complex Systems Perspective.

Advances in Strategic Management, 25: 67-

129.

Dagnino GB, Pisano V (2008). Unpacking the

champion of acquisitions: The key figure in

the execution of the post-acquisition

integration process. In Cooper CL,

Finkelstein S (eds.). Advances in mergers

and acquisitions. Edited by Emerald Group

Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 51-69.

Dixit AK, Pindyck RS (1994). Investment Under

Uncertainty. Princeton University Press,

Princeton.

Ficery K, Herd T, Pursche B (2007). Where has all

the synergy gone? The M&A puzzle. Journal

of Business Strategy, 28(5): 29-35.

Finkelstein S, Haleblian J (2002). Understanding

acquisition performance: The role of transfer

effects. Organization Science, 13(1): 36-47.

Ghosh A (2002). Does Operating Performance

Really Improve Following Corporate

Acquisition?. Journal of Corporate Finance,

7(2): 151-178.

Gold B (1981). Changing Perspectives on Size,

Scale, and Returns: An Interpretive Survey.

Journal of Economic Literature, 19(1): 533.

Graebner ME, Eisenhardt KM, Roundy PT (2010).

Success and Failure in Technology

Acquisitions: Lessons for Buyers and Sellers.

Academy of Management Perspectives.

24(3): 73 92.

Grant RM (1996). Toward a knowledge-based

theory of the firm. Strategic Management

Journal. 17 (Winter Special Issue), 109122.

Gruca TS, Nath D, Mehara A (1997). Exploiting

Synergy for Competitive Advantage. Long

Range Planning, 30(4): 605-611.

Haleblian J, Devers CE, McNamara G, Carpenter

MA, Davison RB (2009). Taking Stock of

What We Know about Mergers and

Acquisitions: A Review and Research

Agenda. Journal of Management, 35: 469-

502.

Heron R, Lie E (2002). Operating Performance and

the Method of Payment in Takeovers.

Journal of Financial and Quantitative

Analysis, 37(1): 137-156.

Hill CWL (1988). Differentiation versus Low Cost

or Differentiation and Low Cost: A

Contingency Framework. Academy of

Management Review, 13(3): 401412.

Hitt M, King D, Krishnan H, Makri M, Schijven M

(2009). Mergers and Acquisitions:

Overcoming Pitfalls, Building Synergy, and

Creating Value. Business Horizons, 52(6):

523-529.

Hitt MA, Harrison JS, Ireland RD (2001). Mergers

and Acquisitions: A Guide to Creating Value

for Stakeholders. Oxford University Press:

Oxford, U.K.

Ismail TH, Abdou AA, Annis RM (2011). Review

of Literature Linking Corporate Performance

to Mergers and Acquisitions. The Review of

Financial and Accounting Studies, 1:89-103.

Keller KL (2003). Strategic Brand Management:

Building, Measuring, and Managing Brand

Equity, 2

nd

edition, Prentice-Hall, New

Jersey, USA

King D, Dalton D, Daily C, Covin J (2004). Meta-

Analysis of Post-Acquisition Performance:

Identifications of Unidentified Moderators.

Caspian Journal of Applied Sciences Research, 1(12), pp. 25-38, 2012

37

Strategic Management Journal, 25(2): 187-

200.

Kotler P (1992). Marketing Management. Analysis

Planning, Implemetation and Controll. 7th

ed, Prentice-Hall, New York, USA

Krishnamurti C, Vishwanath SR, (2008). Mergers,

Acquisitions and Corporate Restructuring.

SAGE Publications, Los Angeles CA, USA.

Krishnan HA, Hitt MA, Park D, (2007).

Acquisition premiums, subsequent workforce

reductions, and post-acquisition

performance. Journal of Management

Studies, 44(5): 709-732.

Laamanen T. (2007). On the role of acquisition

premium in acquisition research. Strategic

Management Journal, 28(13): 1359-1369.

Lambrecht BM (2004). The Timing and Terms of

Mergers Motivated by Economies of Scale.

Journal of Financial Economics, 72(1): 41

62.

Lewellen W, Loderer C, Rosenfeld A (1995).

Merger Decisions and the Executive Stock

Ownership in Acquiring Firms. Journal of

Accounting and Economics, 7(1-3): 209-231.

Lewellen WG (1971). A pure financial rationale

for the conglomerate merger. Journal of

Finance, 26(1): 521-537.

Link NL (1988). Acquisition as Source of

Technological Innovation. Merger &

Acquisition, nov./dec.: 36-39.

Makri M, Hitt MA, Lane PJ (2010).

Complementary Technologies, Knowledge

Relatedness, and Invention Outcomes in

High Technology Mergers and Acquisitions.

Strategic Management Journal, 31(6): 602

628.

Maloney M, McCormick R, Mitchell M (1993).

Managerial decision making and capital

structure. Journal of Business, 66(2): 189-

217.

Martinez E, Pina MJ (2003). The negative impact

of brand extension on parent brand image.

Journal of Brand Management, 12(7): 432-

448.

Massari M (1998). Finanza aziendale. Valutazione.

McGraw Hill, Milano.

McGrath RG, Ferrier W, Mendelow A (2004).

Real options as engines of choice and

heterogeneity. Academy of Management

Review, 29(1): 86-101

Megginson W, Morgan A, Nail L (2004). The

Determinants of Positive Long-Term

Performance in Strategic Merger: Corporate

Focus and Cash. Journal of Banking and

Finance. 28(3): 523-552.

Meglio O, Capasso A (2012). The Evolving Role

of Mergers and Acquisitions in Competitive

Strategy Research. In: Dagnino GB. The

Handbook of Research on Competitive

Strategy. Edward Elgar Cheltenham.

Mitchell W, Shaver JM (2003). Who Buys What?

How Integration Capability Affects

Acquisition Incidence and Target Choice.

Strategic Organization, 1(2): 171-201.

Mocciaro Li Destri A, Dagnino GB (2012).

Learning to Synthesize Contradictions: An

Austrian Approach to Bridging Time

Concepts in the Strategic Theory of The

Firm. International Journal of Strategic

Change Management, 4(2): 99-128.

Mocciaro Li Destri A, Min A (2009). Coopetitive

dynamics in distribution channel

relationships. Finanza Marketing e

Produzione, 2: 1-21.

Mocciaro Li Destri A, Min A (2010).

Levoluzione delle relazioni fra industria e

distribuzione in Italia nel XX secolo. Annali

della Facolt di Economia dellUniversit

degli studi di Palermo.

Mocciaro Li Destri A., Picone P. M. & Min A

(2012). Bringing Strategy Back into

Financial Systems of Performance

Measurement: Integrating EVA and PBC,

Business System Review, 1(1): 85-102

Payne AF (1987). Approaching acquisitions

strategically. Journal of General

Management, 13(2): 5-27.

Perry M (1989). Vertical Integration: Determinants

and Effects, in R. Schmalensee, Willing R.D.

(a cura di) Handbook of Industrial

Organization, vol. I, North Holland, New

York.

Picone, PM (2012). Conglomerate Diversification

Strategy and Corporate Performance.

Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation,

University of Catania, Italy,

http://hdl.handle.net/10761/1167

Porter M (1985). Competitive Advantage, Free

Press. New York, USA.

Powell WW, Koput KW, Smith-Doerr L (1996).

Interorganizational Collaboration and the

Locus of Innovation Networks of Learning in

Biotechnology. Administrative Science

Quarterly, 41(1): 116 145.

Ramaswamy KP, Waegelein J (2003). Firm

Financial Performance Following Mergers.

Review of Quantitative Finance and

Accounting, 20(2): 115-126.

Reddy SK, Holak S, Bhat S (1994). To Extend or

not to Extend: Success Determinants of Line

Mocciaro Li Destri et al.

From Strategic Fit to Synergy Evaluation in M&A Deals

36

Extensions. Journal of Marketing Research,

31(2): 243-262.

Roedder JD, Loken B. (1993). Diluting brand

beliefs: when do brand extensions

have a negative impact?. Journal of

Marketing. 57(3): 71-84.

Salant SW, Switzer S, Reynolds RJ (1983). Losses

from Horizontal Mergers: the Effects of an

Exogenous Change in Industry Structure on

Cournot-Nash Equilibrium. Quarterly

Journal of Economics, 98(2): 185-199.

Saxenian, AL (1994). Regional Advantage.

Harvard University Press, Cambridge.

Scherer FM (1980). Industrial Market Structure

and Market Performance. Rand McNally:

Chicago, IL.

Schweiger DM, Lipper RL (2005). Integration:

The Critical Link in M&A Value Creation

in Stahl GK, Mendenhall ME, Mergers and

Acquisitions Managing Culture and Human

Resources, 17-45.

Schweitzer M, Trossmann E, Lawson G (1992).

Break-even analysis: basic models, variants,

extensions, John Wiley & Sons.

Shelton LM (1988). Strategic Business Fits and

Corporate Acquisition: Empirical Evidence.

Strategic Management Journal, 9(3): 279-

287.

Shimizu K, Hitt MA (2004). Strategic flexibility:

Organizational preparedness to reverse

ineffective strategic decisions. Academy of

Management Executive, 18 (4): 44-59.

Sirower M (1997) The synergy trap: how

companies lose the acquisition game, The

Free Press, New York.

Sirower ML, Sahni S (2006). Avoiding the

Synergy Trap: Practical Guidance on

M&A Decisions for CEOs and Boards.

Journal of Applied Corporate Finance, 18(3):

8395.

Smit HTJ, Trigeorgis L (2004) Strategic

Investment: Real Options and Games,

Princeton University Press: New Jersey.

USA.

Teerikangas S, Vry P, Pisano V (2011).

Integration managers value capturing roles

and acquisition performance, Human

Resource Management, 50(5): 651-683.

Tse T, Soufani K (2001). Wealth Effect of

Takeovers in Merger Activity Eras:

Empirical Evidence from the UK.

International Journal of Economics of

Business, 8(3): 365-377.

Valentini G (2012). Measuring the Effect of M&A

on Patenting Quantity and Quality. Strategic

Management Journal, 33(3): 336346.

Very P (2011). Acquisition performance and the

Quest for the Holy Grail. Scandinavian

Journal of Management, 27(4): 434-437.

Williamson OE (1971). The Vertical Integration of

Production: Market Failure Considerations.

American Economic Review, 61(2): 112-

123.

Yook KC (2004). The Measurement of Post-

Acquisition Performance Using EVA.

Quarterly Journal of Business & Economics,

43 (3&4): 67- 84.

Zanetti L (2000). La valutazione delle acquisizioni.

Egea, Milano.

Zattoni A (2000), Economia e governo dei gruppi

aziendali. Egea, Milano.

Zimmer MR, Bhat S (2004). The reciprocal effects

of extension quality and fit on parent brand

attitude. Journal of Product Brand

Management, 17(1): 37- 46.

Zollo M, Meier D (2008). What Is M&A

Performance?. Academy of Management

Perspectives, 22(3): 55-77.

Zollo M, Singh H (2004). Deliberate Learning in

Corporate Acquisitions: Post-Acquisition

Strategies and Integration Capabilities in

U.S. Bank Mergers. Strategic Management

Journal, 25(13): 1233-1256.

38

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- Effect of Millimeter Waves With Low Intensity On Peroxidase Total Activity and Isoenzyme Composition in Cells of Wheat Seedling ShootsDokumen7 halamanEffect of Millimeter Waves With Low Intensity On Peroxidase Total Activity and Isoenzyme Composition in Cells of Wheat Seedling ShootsAmin MojiriBelum ada peringkat

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5795)

- Comparison of The Physical Characteristics and GC/MS of The Essential Oils of Ocimum Basilicum and Ocimum SanctumDokumen10 halamanComparison of The Physical Characteristics and GC/MS of The Essential Oils of Ocimum Basilicum and Ocimum SanctumAmin MojiriBelum ada peringkat

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- Effect of Processing Variables On Compaction and Relaxation Ratio of Water Hyacinth BriquettesDokumen9 halamanEffect of Processing Variables On Compaction and Relaxation Ratio of Water Hyacinth BriquettesAmin MojiriBelum ada peringkat

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- Full Length Research Paper: ISSN: 2322-4541 ©2013 IJSRPUBDokumen7 halamanFull Length Research Paper: ISSN: 2322-4541 ©2013 IJSRPUBAmin MojiriBelum ada peringkat

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (588)

- Factors Influencing Anemia and Night Blindness Among Children Less Than Five Years Old (0 - 4.11 Years) in Khartoum State, SudanDokumen13 halamanFactors Influencing Anemia and Night Blindness Among Children Less Than Five Years Old (0 - 4.11 Years) in Khartoum State, SudanAmin MojiriBelum ada peringkat

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (74)

- PFRS 13 - Fair Value MeasurementDokumen7 halamanPFRS 13 - Fair Value MeasurementMary Yvonne AresBelum ada peringkat

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- Axis BankDokumen5 halamanAxis Bankvaibhav tanejaBelum ada peringkat

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (895)

- End User License Agreement BOOM LIBRARY For Single Users IMPORTANT-READ CAREFULLY: This BOOM Library End-User License Agreement (Or "EULA")Dokumen3 halamanEnd User License Agreement BOOM LIBRARY For Single Users IMPORTANT-READ CAREFULLY: This BOOM Library End-User License Agreement (Or "EULA")jumoBelum ada peringkat

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- Operations and Productivity SlidesDokumen47 halamanOperations and Productivity SlidesgardeziiBelum ada peringkat

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (400)

- AccountDokumen47 halamanAccountAshwani KumarBelum ada peringkat

- Principles of Marketing (Q-1 M-1) - Lolo - GatesDokumen5 halamanPrinciples of Marketing (Q-1 M-1) - Lolo - GatesCriestefiel LoloBelum ada peringkat

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (345)

- PACEDokumen5 halamanPACEJoanne DawangBelum ada peringkat

- TSmunt BM 711 Ch2 HandoutDokumen3 halamanTSmunt BM 711 Ch2 HandoutShelbyBelum ada peringkat

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- Dissertation FinalDokumen83 halamanDissertation FinalSaurabh YadavBelum ada peringkat

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- PP Presentation Q 15 ADokumen8 halamanPP Presentation Q 15 ARita LakhsmiBelum ada peringkat

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2259)

- Yahoo Consumer Direct Marries Purchase Metrics To Banner AdsDokumen4 halamanYahoo Consumer Direct Marries Purchase Metrics To Banner AdsTengku Muhammad Wahyudi100% (1)

- Marcelo Dos SantosDokumen42 halamanMarcelo Dos SantosIndrama PurbaBelum ada peringkat

- 19llb082 - Banking Law Project - 6th SemDokumen25 halaman19llb082 - Banking Law Project - 6th Semashirbad sahooBelum ada peringkat

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (266)

- Checklist - FF (New) (Blad) - NvoccDokumen1 halamanChecklist - FF (New) (Blad) - NvoccUnicargo Int'l ForwardingBelum ada peringkat

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- A Summer Training Project ReportDokumen17 halamanA Summer Training Project ReportAman Prakash0% (1)

- Financial Management - FSADokumen6 halamanFinancial Management - FSAAbby EsculturaBelum ada peringkat

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- Business Finance 2.2: Financial Ratios: Lecture NotesDokumen16 halamanBusiness Finance 2.2: Financial Ratios: Lecture NotesElisabeth HenangerBelum ada peringkat

- Accounting For OverheadsDokumen9 halamanAccounting For OverheadsAnimashaun Hassan OlamideBelum ada peringkat

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- "Goods Includes All Chattels Personal But Not Things in Action Money of Legal Tender in The Philippines. The Term Includes Growing Fruits CropsDokumen7 halaman"Goods Includes All Chattels Personal But Not Things in Action Money of Legal Tender in The Philippines. The Term Includes Growing Fruits Cropsariane marsadaBelum ada peringkat

- Entrepreneurship AssignmentDokumen7 halamanEntrepreneurship AssignmentMazhar ArfinBelum ada peringkat

- Brandon Hina ResumeDokumen1 halamanBrandon Hina Resumeapi-490908943Belum ada peringkat

- Manual For Discounting Oil and Gas IncomeDokumen9 halamanManual For Discounting Oil and Gas IncomeCarlota BellésBelum ada peringkat

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (121)

- Dubai Islamic FinanceDokumen5 halamanDubai Islamic FinanceKhuzaima ShafiqBelum ada peringkat

- Advanced Cost Accounting: Marginal CostingDokumen41 halamanAdvanced Cost Accounting: Marginal CostingManaliBelum ada peringkat

- Increment Letter Format - 1: EnclosureDokumen3 halamanIncrement Letter Format - 1: Enclosurenasir ahmedBelum ada peringkat

- MJ Ebook Brand Storytelling GuideDokumen17 halamanMJ Ebook Brand Storytelling GuideRuicheng ZhangBelum ada peringkat

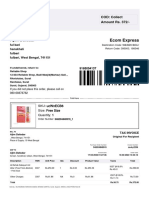

- Sub Order Labels 94ce8e7a 1b4d 4d5b Aac6 23950027e54dDokumen2 halamanSub Order Labels 94ce8e7a 1b4d 4d5b Aac6 23950027e54dDaryaee AhmedBelum ada peringkat

- Bhanu Advani - Prospectus PDFDokumen19 halamanBhanu Advani - Prospectus PDFBhanu AdvaniBelum ada peringkat

- Effective SME Family Business Succession StrategiesDokumen9 halamanEffective SME Family Business Succession StrategiesPatricia MonteferranteBelum ada peringkat

- VC Lab Cornerstone LPADokumen34 halamanVC Lab Cornerstone LPApyrosriderBelum ada peringkat

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)