The Effects of Smoking On Dental Care Utilization and Its Costs in Japan

Diunggah oleh

Dhanty WidyanisitaDeskripsi Asli:

Judul Asli

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

The Effects of Smoking On Dental Care Utilization and Its Costs in Japan

Diunggah oleh

Dhanty WidyanisitaHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

The Effects of Smoking on Dental Care Utilization and Its Costs in Japan

Abstract

Smoking has been established as an important risk factor for periodontal disease and tooth loss. The purpose of this study was a prospective evaluation of the effects of smoking on dental care utilization and its costs, based on data from 5712 males aged 2059 yrs. Age, dental health behavior, and history of diabetes were adjusted in a multivariate analysis. Current smokers accrued 14% higher dental care costs than never-smokers over a five-year period. This difference in annual dental care costs was mainly attributable to the increased percentage of participants in the higher dental care cost category among current smokers. There was no clear trend identified for the dose-dependent effects of smoking on dental care utilization and its costs. Past smokers incurred lower dental care costs compared with current smokers. Smoking may have played a key role in the increment of dental care utilization and its costs via deterioration in oral conditions. The authors identified that current smokers accrued 14% higher dental care costs than never-smokers over a five-year period.

INTRODUCTION

Several studies have shown that smokers have an increased risk of incurring periodontal diseases and having poor oral health status. In 2004, current smoking rates among Japanese male adults, at 43.3%, were higher than in other developed countries (Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, 2006). One study reported that current smokers among Japanese male workers had a higher risk of periodontal disease, tooth loss, and caries, but they had a reduced risk of gum bleeding (Ide et al., 2002). In a cross-sectional study using a national database in Japan, smoking was significantly associated with tooth loss, and a dose-response relationship between lifetime exposure and tooth loss was also observed (Hanioka et al., 2007). Since a positive relationship between smoking and risk of oral conditions (e.g., periodontal disease and tooth loss) has been quite consistent in several epidemiologic studies in Japan, we hypothesized that dental care utilization and its costs are affected by smoking status. Dental health behavior is related to smoking status, and smokers are less likely to be concerned for their own health. Unhealthy lifestyle behaviors, including smoking, have been associated with poor dental health behavior, e.g., less-frequent toothbrushing, less use of extra cleaning methods, more use of sugar in coffee or tea, and longer time since last dental visit (Sakki et al., 1998). A few studies have reported lower use of dental services among smokers, after adjustment for confounding factors such as age, gender, and socio-economic status (Mucci and Brooks, 2001; Drilea et al., 2005). However, these analyses were derived from crosssectional data, so dental visits might be influenced by health-seeking behavior rather than by behavior in response to need for dental care. Therefore, after adjustment for related dental health characteristics, a prospective study is adequate to examine the impact of smoking on dental care utilization and costs. Japan has a national health insurance system to ensure that anyone can receive necessary health care, so in principle every resident of Japan is enrolled in some form of health insurance plan. Most dental care costs are covered by health insurance, excluding that of orthodontic and implant treatments and partly excluding prosthetic appliances. Under this system, fees for dental services are standardized nationwide. The costs and utilization of health services associated with dental care can be calculated on the basis of claims over given periods, since such claims accurately reflect most expenditures for dental services received. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the effects of smoking on dental care utilization and its costs, based on data from civil officers worksite dental examinations and health insurance claims. We used prospective data to assess whether smokers are likely to receive

dental care, while accounting for confounding factors including age, dental health behavior, and history of diabetes.

MATERIALS & METHODS

Data Source

The base population consisted of civil service officers (about 25,000) from a prefecture in southwestern Japan. These officers were responsible for administering various social welfare programs, including health insurance and welfare pensions, in accordance with Japanese government regulations. They had received biennial dental examinations, and the data analyzed for this study were derived from the examinations conducted between June, 2000, and February, 2001 by seven trained dentists. Periodontal status was defined according to the Community Periodontal Index of Treatment Needs (CPITN) (Ainamo et al., 1982). The occurrence of decayed, filled, and missing teeth was recorded separately for each tooth (World Health Organization, 1987). By means of a questionnaire given at the dental examinations, we also collected information on: smoking status; self-rated oral health; dental health behavior assessed as sufficient time taken for toothbrushing; use of floss or interdental brushes; consumption of sweet drinks, candies, or chewing gum; and history of diabetes. Smoking status was defined as never-smoker, past smoker, or current smoker. Current smokers were also asked about the number of cigarettes they smoked per day. We obtained data on the utilization and costs of dental care, derived from health insurance claims made between April, 2000, and March, 2005, which included the number of visit-days and the costs incurred in the acquisition of dental care. Dental examination data were linked with the health insurance claim files by ID number. The present study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Medical Care and Research, University of Occupational and Environmental Health, Japan. Informed consent was obtained at the group level after the study objective and the confidentiality of the data were explained to the respective leaders.

Study Participants

Of the 11,813 eligible individuals who were employed for the full study period, 73.4% had received a dental examination. Because 12 of these participants were not eligible for the perio dontal examination, due to their being not dentate, we selected 8653 participants. In the present study, only participants aged 2059 yrs as of April 1, 2000 (n = 8607), were included. Females were excluded from the analysis because of their low smoking rate (1.7%). Of the 5715 male participants, those who did not provide sufficient information on smoking status were excluded, so 5712 males were finally analyzed.

Statistical analysis

Crude visit rates were calculated as the percentage of participants who had visited a dental clinic during the study period. The odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) of smoking on dental care use were estimated by multiple logistic regression, with never-smokers as a reference. Adjusted means of annual dental care costs and number of dental visits were examined by analysis of covariance. In addition, multiple comparisons were performed with Tukeys method. Multivariate models included the following variables as covariates: age (yrs), history of diabetes (yes or none), long brushing time (> 5 min at least once a day, or none), use of floss or interdental brushes (> 23 times/wk, or hardly ever), intake of sweet drinks (> 23 times/wk, or hardly ever), and consumption of candies or chewing gum (> 23 times/wk, or hardly ever). The frequency of missing responses for dental health behavior items was very low (0.10.2%), so they were replaced by the hardly ever responses for the corresponding item. First, participants were categorized into three groups: never-, past, and current smokers. We estimate the annual dental care costs and numbers of visits by dividing the cumulative amount for the study period by the number of data-years included in this study. Second, an

analysis was performed with data only for current smokers, classified into three categories: those who consumed < 20 cigarettes/day (light smoker), those who consumed 2029 cigarettes/day (moderate smoker), and those who consumed 30 cigarettes/day (heavy smoker). Third, to compare the proportion of participants with high dental care costs, we divided the annual dental care cost into four categories: 0 yen (no-cost category), 120,000 yen (low-cost category), 20,00150,000 yen (intermediate-cost category), and 50,001 yen or more (high-cost category). P value was calculated by the chi-square test. The above calculations were carried out with Statistical Analysis System Version 8.02.

RESULTS

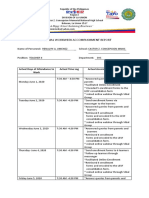

The percentages of never-, past, and current smokers at baseline were 36.0%, 13.5%, and 50.5%, respectively. Never-smokers tended to use floss or interdental brushes; 20.1%, 18.4%, and 14.2% of never-smokers, past smokers, and current smokers, respectively, used these more than 23 times per week (p < 0.0001). The proportions of participants with periodontitis (CPITN code 3 or 4) were 35.0%, 45.1%, and 50.1%, respectively, and significantly differed among the three groups (p< 0.0001). The dental visit rate of past smokers was highest, although this difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.092). Current smokers had a higher number of annual dental visitdays than never-smokers (p = 0.003). The annual dental care cost of current smokers was highest among the three smoking status groups, at 14% higher than never-smokers (p < 0.0001). There was also a statistically significant difference in the annual dental care costs between past smokers and current smokers (p = 0.048). Among current smokers, 46.8% were moderate smokers, consuming 2029 cigarettes/day, and 32.3% were heavy smokers, consuming 30 cigarettes/day. The differences in the number of current smokers in are due to missing data on the number of cigarettes smoked per day (n = 14). The dose- response relationship for current smokers was not clear; there were no statistically significant differences in either annual dental care costs or visits according to smoking status, the highest being among heavy smokers. The distribution of the four cost categories (no-, low-, intermediate-, and high-cost) is shown in the Fig, and it significantly differs among the three groups (p = 0.0009). The percentages of participants in the intermediate- and high-cost categories among current, past, and never-smokers were 36.0%, 34.1%, and 30.4%, respectively. The percentage in the low-cost category was lowest among current smokers; the percentages of current, past, and never-smokers were 46.6%, 50.1%, and 50.4%, respectively.

DISCUSSION

Our study indicated that smoking was associated with dental care cost increases, independent of other risk factors, in this prospective cohort study of male workers. Current smokers accrued 14% higher dental care costs than never-smokers over a five-year period. This difference in annual dental care costs was mainly attributable to the increased percentage of participants in the higher dental care cost category among current smokers. Furthermore, past smokers incurred lower dental care costs compared with current smokers. The findings of this study were based on prospective data, adjusted for age, dental health behaviors, and history of diabetes. Previous cross-sectional studies suggested that smokers were less likely to go to the dentist, even with adjustment for confounding factors such as socioeconomic status and awareness of health-related information. In a population-based survey in the USA, long-term smokers were less likely to have had a recent dental visit (OR = 0.69; 95% CI, 0.480.99) (Mucci and Brooks, 2001). Similar results for smoking and dental visits were found in a nationally representative sample of US adults (Drilea et al., 2005). Both studies controlled for related socio-economic status (SES) factors, such as education and dental insurance. These findings indicate a low concern for their health among smokers. In our study, current smokers

were also less likely to have had at least one dental visit compared with never-smokers, with 41.8% of current smokers having visited a dental clinic during the first year compared with 45.8% of never-smokers. Therefore, the excess dental care costs incurred by smokers would be more appropriately estimated by a longitudinal study. As expected, the results of our study indicated that smoking is incrementally associated with dental care costs and number of visits during a period of 5 yrs. Our findings at baseline showed that smoking had a statistically significant association with periodontal conditions, dental caries, and tooth loss. Smoking has been established as a strong predictor of oral disease in several longitudinal studies (Machtei et al., 1999; Bergstrm et al., 2000; Copeland et al., 2004). In addition, it has also been reported that the healing response subsequent to various periodontal therapies is weaker among current smokers compared with non-smokers (Preber and Bergstrm, 1990; Kaldahl et al., 1996). A previous study has associated smoking with a higher risk of tooth loss among adults even as young as 30 yrs, after adjustment for socio- economic and behavioral factors (Ylostalo et al., 2004). Smokers aged 3549 yrs exhibited a significantly larger number of decayed and filled tooth surfaces than did non-smokers (Axelsson et al., 1998). Smoking can lead to tooth staining due to the nicotine and tar content of cigarettes, so professional prophylaxis procedures in a dental clinic may be more frequently required for removal of abundant tooth staining in current smokers than in non-smokers. The above findings can explain why our study found that current smokers had the highest dental care costs and number of visits. We found a decrease in dental care costs among past smokers as compared with current smokers. Smoking cessation was found to restore periodontal health status, with a reduction of probing depth and modulation of subgingival microflora within a 12-month period (Grossi et al., 1997; Preshaw et al., 2005). The risk of tooth loss decreased with increasing time since smoking cessation, but it took more than 10 yrs of cessation for the risk to reach that of never-smokers (Dietrich et al., 2007). The apparent difference in dental care costs between current and past smokers in our study may be explained partly by the presence of oral conditions besides periodontal disease, such as caries and tooth staining. Quitting smoking may have a beneficial effect in reducing dental care costs. The dose-response relationships between smoking and oral conditions such as periodontal disease and tooth loss have been previously reported (Ide et al., 2002; Dietrich et al., 2007; Hanioka et al., 2007). However, in the present study, an increase in dental care costs and number of visits according to the number of cigarettes smoked per day was not clear among current smokers. Information on smoking habits was collected only at baseline. It is well-known that changes in health-related habits occur over time. It has been reported that a decrease in the number of cigarettes consumed per day, correlated with aging, was observed during a five-year follow-up period in a cohort study (Kawado et al., 2005). This type of change may result in underestimation of the dose-response magnitude. A limitation of our data was that smoking status was determined solely by self-reported questionnaires, which may be less accurate than determination by urinary cotinine as the gold standard. Econometric studies that control for related risk factors provide more reliable results, so we did consider dental health behaviors as confounding factors in our study. It has been suggested that socioeconomic status is related to dental care utilization (Manski et al., 2004; Drilea et al., 2005), but the present analysis did not take socio-economic factors into account. Since all our study participants were civil officers from one prefecture and were covered by health insurance that is strictly standardized nationwide by the government, we supposed that our study participants were sufficiently homogeneous and did not require adjustment for SES factors. Therefore, we can conclude that smoking could be viewed as a predictor for high dental care costs. The impact of smoking on medical care expenditure has been well-documented in the literature over the last several decades. A more recent econometric study reported that costs attributable to smoking comprised from 6 to 9% of personal health expenditures (Max, 2001). Approximately 4% of total medical costs were attributable to smoking among the population aged 45 yrs and older in a rural Japanese community (Izumi et al., 2001). The relationship between smoking and dental care costs and utilization has received little attention in the

literature. Further research should focus on economic assessments and real costs, to understand how smoking affects social burdens in oral health.

REFERENCES

1. Ainamo J, Barmes D, Beagrie G, Cutress T, Martin J, Sardo-Infirri J (1982). Development of the World Health Organization (WHO) community periodontal index of treatment needs (CPITN). Int Dent J 32:281291. 2. Axelsson P, Paulander J, Lindhe J (1998). Relationship between smoking and dental status in 35-, 50-, 65-, and 75-year-old individuals. J Clin Periodontol 25:297305. 3. Bergstrm J, Eliasson S, Dock J (2000). A 10-year prospective study of tobacco smoking and periodontal health. J Periodontol 71:13381347. 4. Copeland LB, Krall EA, Brown LJ, Garcia RI, Streckfus CF (2004). Predictors of tooth loss in two US adult populations. J Public Health Dent 64:3137. 5. Dietrich T, Maserejian NN, Joshipura KJ, Krall EA, Garcia RI (2007). Tobacco use and incidence of tooth loss among US male health professionals. J Dent Res 86:373 377. 6. Drilea SK, Reid BC, Li CH, Hyman JJ, Manski RJ (2005). Dental visits among smoking and nonsmoking US adults in 2000. Am J Health Behav 29:462471. 7. Grossi SG, Zambon J, Machtei EE, Schifferle R, Andreana S, Genco RJ, et al. (1997). Effects of smoking and smoking cessation on healing after mechanical periodontal therapy. J Am Dent Assoc 128: 599607. 8. Hanioka T, Ojima M, Tanaka K, Aoyama H (2007). Relationship between smoking status and tooth loss: findings from national databases in Japan. J Epidemiol 17:125132. 9. Ide R, Mizoue T, Ueno K, Fujino Y, Yoshimura T (2002). Relationship between cigarette smoking and oral health status. Sangyo Eiseigaku Zasshi 44:611. 10. Izumi Y, Tsuji I, Ohkubo T, Kuwahara A, Nishino Y, Hisamichi S (2001). Impact of smoking habit on medical care use and its costs: a prospective observation of National Health Insurance beneficiaries in Japan. Int J Epidemiol 30:616621. 11. Kaldahl WB, Johnson GK, Patil KD, Kalkwarf KL (1996). Levels of cigarette consumption and response to periodontal therapy. J Periodontol 67:675681. 12. Kawado M, Suzuki S, Hashimoto S, Tokudome S, Yoshimura T, Tamakoshi A (2005). Smoking and drinking habits five years after baseline in the JACC study. J Epidemiol 15(Suppl 1):56S66S. 13. Machtei EE, Hausmann E, Dunford R, Grossi S, Ho A, Davis G, et al. (1999). Longitudinal study of predictive factors for periodontal disease and tooth loss. J Clin Periodontol 26:374380. 14. Manski RJ, Goodman HS, Reid BC, Macek MD (2004). Dental insurance visits and expenditures among older adults. Am J Public Health 94:759764. 15. Max W (2001). The financial impact of smoking on health-related costs: a review of the literature. Am J Health Promot 15:321331. 16. Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Japan (2006). The National Nutrition Survey in Japan, 2004. Tokyo: Dai-ichi Shuppan.

17. Mucci LA, Brooks DR (2001). Lower use of dental services among long term cigarette smokers. J Epidemiol Community Health 55: 389393. 18. Preber H, Bergstrm J (1990). Effect of cigarette smoking on periodontal healing following surgical therapy. J Clin Periodontol 17:324328. 19. Preshaw PM, Heasman L, Stacey F, Steen N, McCracken GI, Heasman PA (2005). The effect of quitting smoking on chronic periodontitis. J Clin Periodontol 32:869 879. 20. Sakki TK, Knuuttila ML, Anttila SS (1998). Lifestyle, gender and occupational status as determinants of dental health behavior. J Clin Periodontol 25:566570. 21. World Health Organization (1987). Oral health surveys: basic methods. 3rd ed. Geneva: World Health Organization. 22. Ylostalo P, Sakki T, Laitinen J, Jarvelin MR, Knuuttila M (2004). The relation of tobacco smoking to tooth loss among young adults. Eur J Oral Sci 112:121126.

RESUME The Effects of Smoking on Dental Care Utilization and Its Costs in Japan (Pengaruh Merokok pada Pemanfaatan Perawatan Gigi dan Biayanya di Jepang)

Beberapa studi telah menunjukkan bahwa perokok memiliki peningkatan risiko timbulnya penyakit periodontal dan memiliki status kesehatan mulut yang buruk. Pada tahun 2004, tingkat merokok di kalangan orang dewasa laki-laki Jepang, sebesar 43,3%, lebih tinggi dari di negara-negara maju lainnya. Satu studi melaporkan bahwa perokok saat ini di kalangan pekerja laki-laki Jepang memiliki risiko lebih tinggi penyakit periodontal, kehilangan gigi, dan karies, tetapi mereka memiliki penurunan risiko perdarahan gusi. Dalam studi cross-sectional menggunakan database nasional di Jepang, merokok jelas terkait dengan kehilangan gigi, dan hubungan dosis-respons antara paparan seumur hidup dan kehilangan gigi juga diamati. Karena hubungan yang positif antara merokok dan risiko kondisi oral (misalnya, penyakit periodontal dan kehilangan gigi) telah cukup konsisten dalam studi beberapa epidemiologi di Jepang, telah diduga bahwa pemanfaatan perawatan gigi dan biayanya dipengaruhi oleh status merokok. Perilaku Kesehatan Gigi terkait dengan status merokok, dan perokok cenderung khawatir untuk kesehatan mereka sendiri. Perilaku gaya hidup yang tidak sehat, termasuk merokok, telah dihubungkan dengan perilaku kesehatan gigi yang buruk, misalnya, kurang sering menyikat gigi, kurang penggunaan metode pembersihan ekstra, lebih banyak minum gula dalam kopi atau teh, dan tidak pernah memeriksa gigi secara rutin. Beberapa penelitian melaporkan bahwa penggunaan layanan jasa dokter gigi yang lebih rendah di kalangan perokok. Namun, analisis ini berasal dari data cross-sectional, sehingga kunjungan ke dokter gigi mungkin dipengaruhi oleh perilaku mencari kesehatan bukan oleh perilaku kebutuhan perawatan gigi. Oleh karena itu, setelah disesuaikan dengan karakteristik terkait kesehatan gigi, sebuah penelitian prospektif adalah cukup untuk menguji dampak rokok terhadap pemanfaatan dan biaya perawatan gigi. Jepang memiliki sistem asuransi kesehatan nasional untuk memastikan bahwa setiap orang dapat menerima perawatan kesehatan yang diperlukan, sehingga pada prinsipnya setiap warga Jepang terdaftar dalam beberapa bentuk program asuransi kesehatan. Sebagian besar biaya perawatan gigi dilindungi oleh asuransi kesehatan, termasuk biaya perawatan ortodontik dan implan dan sebagian tidak termasuk peralatan prostetik. Di bawah sistem ini, biaya untuk layanan kesehatan gigi adalah standar nasional. Biaya dan pemanfaatan pelayanan kesehatan yang berhubungan dengan perawatan gigi dapat dihitung berdasarkan klaim selama periode yang diberikan, karena klaim tersebut secara akurat mencerminkan pengeluaran yang paling banyak untuk layanan kesehatan gigi yang diterima. Tujuan dari penelitian ini adalah untuk mengevaluasi dampak rokok terhadap pemanfaatan perawatan gigi dan biaya, berdasarkan data dari pemeriksaan tempat kerja pejabat sipil dan klaim asuransi kesehatan. Dengan menggunakan data prospektif untuk menilai apakah perokok cenderung untuk menerima perawatan gigi, sedangkan penghitungan untuk faktor pembaur termasuk usia, perilaku kesehatan gigi, dan sejarah diabetes.

Temuan penelitian ini adalah berdasarkan data prospektif, disesuaikan untuk usia, perilaku kesehatan gigi, dan sejarah diabetes. Studi cross-sectional sebelumnya menunjukkan bahwa perokok lebih kecil kemungkinannya untuk datang ke dokter gigi, bahkan dengan penyesuaian untuk faktor pembaur seperti status sosial-ekonomi dan kesadaran informasi kesehatan terkait. Dalam sebuah survei berbasis populasi di Amerika Serikat, perokok jangka panjang kurang memiliki kesadaran untuk melakukan kunjungan ke dokter gigi (OR = 0,69, 95% CI, 0,48-0,99). Temuan ini menunjukkan kepedulian rendah untuk kesehatan gigi di kalangan perokok. Dalam penelitian ini, perokok saat ini juga kurang mungkin memiliki setidaknya satu kunjungan gigi dibandingkan yang bukan perokok, dengan 41,8% dari perokok saat ini setelah mengunjungi sebuah klinik gigi selama tahun pertama dibandingkan dengan 45,8% dari yang bukan perokok. Oleh karena itu, kelebihan biaya perawatan gigi yang dikeluarkan oleh perokok akan lebih tepat diperkirakan melalui studi longitudinal. Seperti yang diharapkan, hasil penelitian ini menunjukkan bahwa merokok secara bertahap dikaitkan dengan biaya perawatan gigi dan jumlah kunjungan selama periode 5 tahun.

Seperti yang telah dikatakan di awal bahwa merokok mempunyai hubungan secara statistik signifikan dengan kondisi periodontal, karies gigi, dan kehilangan gigi. Merokok telah ditetapkan sebagai prediktor yang kuat dari penyakit mulut dalam studi longitudinal. Selain itu, juga telah dilaporkan bahwa respon penyembuhan setelah terapi berbagai periodontal lemah di kalangan perokok dibandingkan dengan non-perokok. Sebuah studi sebelumnya telah dikaitkan merokok dengan risiko tinggi kehilangan gigi di kalangan orang dewasa bahkan semuda 30 tahun, setelah penyesuaian untuk faktor-faktor sosio-ekonomi dan perilaku. Merokok dapat menyebabkan warna gigi menjadi kuning karena kandungan nikotin dan tar (getah tembakau) pada rokok, jadi prosedur yang lebih sulit dan lebih lama di klinik gigi untuk menghapus noda kuning tersebut menjadi lebih sering di kalangan perokok. Temuan di atas dapat menjelaskan mengapa studi ini menemukan bahwa perokok saat ini memiliki biaya perawatan gigi yang lebih besar dan dalam jumlah kunjungan. Dampak merokok terhadap pengeluaran perawatan kesehatan telah terdokumentasi dengan baik dalam literatur selama beberapa dekade terakhir. Sebuah studi ekonometrik yang paling baru melaporkan bahwa biaya yang terkait dengan merokok terdiri 6-9% dari pengeluaran kesehatan pribadi. Sekitar 4% dari total biaya pengobatan yang disebabkan merokok di antara penduduk usia 45 thn dan lebih tua dalam masyarakat Jepang pedesaan. Hubungan antara merokok dan biaya pemanfaatan perawatan gigi mendapat sedikit perhatian dalam literatur. Penelitian lebih lanjut harus fokus pada penilaian ekonomi dan biaya riil, untuk memahami bagaimana merokok mempengaruhi beban sosial dalam kesehatan mulut.

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- Age Related During ChewingDokumen10 halamanAge Related During ChewingDhanty WidyanisitaBelum ada peringkat

- Age Related During ChewingDokumen10 halamanAge Related During ChewingDhanty WidyanisitaBelum ada peringkat

- 2175 1278 1 PBDokumen8 halaman2175 1278 1 PBWan NurulHidayahBelum ada peringkat

- Effect of Dentinal Surface Preparation On Bond Strength PDFDokumen7 halamanEffect of Dentinal Surface Preparation On Bond Strength PDFDhanty WidyanisitaBelum ada peringkat

- The Effect of Abutment Surface Roughness On The Retention ofDokumen5 halamanThe Effect of Abutment Surface Roughness On The Retention ofDhanty WidyanisitaBelum ada peringkat

- Disclosing AgentsDokumen5 halamanDisclosing AgentsDhanty WidyanisitaBelum ada peringkat

- The Effects of Smoking On Dental Care Utilization and Its Costs in JapanDokumen8 halamanThe Effects of Smoking On Dental Care Utilization and Its Costs in JapanDhanty WidyanisitaBelum ada peringkat

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (344)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (73)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2259)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (120)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)

- Creating The HardboiledDokumen20 halamanCreating The HardboiledBen NallBelum ada peringkat

- Pressure Sound MeasurementDokumen47 halamanPressure Sound MeasurementSaleem HaddadBelum ada peringkat

- Digital Signal Processing AssignmentDokumen5 halamanDigital Signal Processing AssignmentM Faizan FarooqBelum ada peringkat

- List of Naruto Char.Dokumen40 halamanList of Naruto Char.Keziah MecarteBelum ada peringkat

- Suicide Prevention BrochureDokumen2 halamanSuicide Prevention Brochureapi-288157545Belum ada peringkat

- 21st Century NotesDokumen3 halaman21st Century NotesCarmen De HittaBelum ada peringkat

- Blood Is A Body Fluid in Human and Other Animals That Delivers Necessary Substances Such AsDokumen24 halamanBlood Is A Body Fluid in Human and Other Animals That Delivers Necessary Substances Such AsPaulo DanielBelum ada peringkat

- Shalini NaagarDokumen2 halamanShalini NaagarAazam AdtechiesBelum ada peringkat

- InvestMemo TemplateDokumen6 halamanInvestMemo TemplatealiranagBelum ada peringkat

- Gender Religion and CasteDokumen41 halamanGender Religion and CasteSamir MukherjeeBelum ada peringkat

- Description of Medical Specialties Residents With High Levels of Workplace Harassment Psychological Terror in A Reference HospitalDokumen16 halamanDescription of Medical Specialties Residents With High Levels of Workplace Harassment Psychological Terror in A Reference HospitalVictor EnriquezBelum ada peringkat

- Fernando Pessoa LectureDokumen20 halamanFernando Pessoa LecturerodrigoaxavierBelum ada peringkat

- Midterm Exam (Regulatory Framework and Legal Issues in Business Law) 2021 - Prof. Gerald SuarezDokumen4 halamanMidterm Exam (Regulatory Framework and Legal Issues in Business Law) 2021 - Prof. Gerald SuarezAlexandrea Bella Guillermo67% (3)

- The Cave Tab With Lyrics by Mumford and Sons Guitar TabDokumen2 halamanThe Cave Tab With Lyrics by Mumford and Sons Guitar TabMassimiliano MalerbaBelum ada peringkat

- Newton's Second LawDokumen3 halamanNewton's Second LawBHAGWAN SINGHBelum ada peringkat

- Summary of All Sequences For 4MS 2021Dokumen8 halamanSummary of All Sequences For 4MS 2021rohanZorba100% (3)

- Invisible Rainbow A History of Electricity and LifeDokumen17 halamanInvisible Rainbow A History of Electricity and LifeLarita Nievas100% (3)

- Fouts Federal LawsuitDokumen28 halamanFouts Federal LawsuitWXYZ-TV DetroitBelum ada peringkat

- Impulsive Buying PDFDokumen146 halamanImpulsive Buying PDFrukwavuBelum ada peringkat

- Brand Zara GAP Forever 21 Mango H&M: Brand Study of Zara Nancys Sharma FD Bdes Batch 2 Sem 8 Brand-ZaraDokumen2 halamanBrand Zara GAP Forever 21 Mango H&M: Brand Study of Zara Nancys Sharma FD Bdes Batch 2 Sem 8 Brand-ZaraNancy SharmaBelum ada peringkat

- Ponty Maurice (1942,1968) Structure of BehaviorDokumen131 halamanPonty Maurice (1942,1968) Structure of BehaviorSnorkel7Belum ada peringkat

- Chapter 6 - Scheduling AlgorithmDokumen42 halamanChapter 6 - Scheduling AlgorithmBinyam KebedeBelum ada peringkat

- How Death Came To The CityDokumen3 halamanHow Death Came To The City789863Belum ada peringkat

- m100 Resume Portfolio AssignmentDokumen1 halamanm100 Resume Portfolio Assignmentapi-283396653Belum ada peringkat

- Erotic Massage MasteryDokumen61 halamanErotic Massage MasteryChristian Omar Marroquin75% (4)

- A Guide To Conducting A Systematic Literature Review ofDokumen51 halamanA Guide To Conducting A Systematic Literature Review ofDarryl WallaceBelum ada peringkat

- Mag Issue137 PDFDokumen141 halamanMag Issue137 PDFShafiq Nezat100% (1)

- Mein Leben Und Streben by May, Karl Friedrich, 1842-1912Dokumen129 halamanMein Leben Und Streben by May, Karl Friedrich, 1842-1912Gutenberg.orgBelum ada peringkat

- Individual Workweek Accomplishment ReportDokumen16 halamanIndividual Workweek Accomplishment ReportRenalyn Zamora Andadi JimenezBelum ada peringkat

- LESSON 6 Perfect TensesDokumen4 halamanLESSON 6 Perfect TensesAULINO JÚLIOBelum ada peringkat