Best Practices For Raising Kids

Diunggah oleh

ddiver1Deskripsi Asli:

Judul Asli

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Best Practices For Raising Kids

Diunggah oleh

ddiver1Hak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Dec 17, 2012 Best Practices for Raising Kids?

Look to Hunter-Gatherers Jared Diamond Hold them, share them, let them run free. Why the traditional way of raising kid s is better than ours. On one of my visits ?to New Guinea, I met a young man named Enu, whose life stor y struck me then as remarkable. Enu had grown up in an area where child-rearing was extremely repressive, and where children were heavily burdened by obligation s and by feelings of guilt. By the time he was 5 years old, Enu decided that he had had enough of that lifestyle. He left his parents and most of his relatives and moved to another tribe and village, where he had relatives willing to take c are of him. There, Enu found himself in an adoptive society with laissez-faire c hild-rearing practices at the opposite extreme from his natal society s practices. Young children were considered to have responsibility for their own actions, an d were allowed to do pretty much as they pleased. For example, if a baby was pla ying next to a fire, adults did not intervene. As a result, many adults in that society had burn scars, which were legacies of their behavior as infants. How We Hold Them: Constant contact between caregiver and baby may contribute to the child s improved neuromotor development. Both of those styles of child-rearing would be rejected with horror in Western i ndustrial societies today. But the laissez-faire style of Enu s adoptive society i s not unusual by the standards of the world s hunter-gatherer societies, many of w hich consider young children to be autonomous individuals whose desires should n ot be thwarted, and who are allowed to play with dangerous objects such as sharp knives, hot pots, and fires. I find myself thinking a lot about the New Guinea people with whom I have been w orking for the last 49 years, and about the comments of Westerners who have live d for years in hunter-gatherer societies and watched children grow up there. Oth er Westerners and I are struck by the emotional security, self-confidence, curios ity, and autonomy of members of small-scale societies, not only as adults but al ready as children. We see that people in small-scale societies spend far more ti me talking to each other than we do, and they spend no time at all on passive en tertainment supplied by outsiders, such as television, videogames, and books. We are struck by the precocious development of social skills in their children. Th ese are qualities that most of us admire, and would like to see in our own child ren, but we discourage development of those qualities by ranking and grading our children and constantly telling them what to do. The adolescent identity crises that plague American teenagers aren t an issue for hunter-gatherer children. The W esterners who have lived with hunter-gatherers and other small-scale societies s peculate that these admirable qualities develop because of the way in which thei r children are brought up: namely, with constant security and stimulation, as a result of the long nursing period, sleeping near parents for several years, far m ore social models available to children through allo-parenting, far more social s timulation through constant physical contact and proximity of caretakers, instan t caretaker responses to a child s crying, and the minimal amount of physical puni shment. Keep Them Close In modern industrial societies today, we follow the rabbit-antelope pattern: the mother or someone else occasionally picks up and holds the infant in order to f eed it or play with it, but does not carry the infant constantly; the infant spe

nds much or most of the time during the day in a crib or playpen; and at night t he infant sleeps by itself, usually in a separate room from the parents. However , we probably continued to follow our ancestral ape-monkey model throughout almo st all of human history, until within the last few thousand years. Studies of mo dern hunter-gatherers show that an infant is held almost constantly throughout t he day, either by the mother or by someone else. When the mother is walking, the infant is held in carrying devices, such as the slings of the !Kung, string bag s in New Guinea, and cradle boards in the north temperate zones. Most hunter-gat herers, especially in mild climates, have constant skin-to-skin contact between the infant and its caregiver. In every known society of human hunter-gatherers a nd of higher primates, mother and infant sleep immediately nearby, usually in th e same bed or on the same mat. A cross-cultural sample of 90 traditional human s ocieties identified not a single one with mother and infant sleeping in separate rooms: that current Western practice is a recent invention responsible for the struggles at putting kids to bed that torment modern Western parents. American p ediatricians now recommend not having an infant sleep in the same bed with its p arents, because of occasional cases of the infant ending up crushed or else over heating; but virtually all infants in human history until the last few thousand years did sleep in the same bed with the mother and usually also with the father , without widespread reports of the dire consequences feared by pediatricians. T hat may be because hunter-gatherers sleep on the hard ground or on hard mats; a parent is more likely to roll over onto an infant in our modern soft beds. How They Play: Treating children as qualitatively similar to grown-ups could hel p them develop into tough and resilient adults. (Photos: Klaus Tiedge / Corbis ( left); Jackie Ellis / Alamy) Even when not sleeping, !Kung infants spend their first year of life in skin-toskin contact with the mother or another caregiver for 90 percent of the time. A !Kung child begins to separate more frequently from its mother after the age of 1 , but those separations are initiated almost entirely by the child itself, in o rder to play with other children. The daily contact time between the !Kung child and caregivers other than the mother exceeds contact time (including contact wi th the mother) for modern Western children. One of the commonest Western devices for transporting a child is the stroller, w hich provides no physical contact between the baby and the caregiver. In many st rollers, the infant is nearly horizontal, and sometimes facing backward. Hence t he infant does not see the world as its caregiver sees the world. In recent deca des in the United States, devices for transporting children in a upright positio n have been more common, such as baby carriers, backpacks, and chest pouches, bu t many of those devices have the child facing backward. In contrast, traditional carrying devices, such as slings or holding a child on one s shoulders, usually p lace the child vertically upright, facing forward, and seeing the same world tha t the caregiver sees. The constant contact even when the caretaker is walking, t he constant sharing of the caregiver s field of view, and transport in the vertica l position may contribute to !Kung infants being advanced (compared to American infants) in some aspects of their neuromotor development. In warm climates, it is practical to have constant skin-to-skin contact between a naked baby and a mostly naked mother. That is more difficult in cold climates. Hence about half of traditional societies, mostly those in the temperate zones, swaddle their infants, i.e., wrap the infant in warm fabric and often strap the infant to a cradle board. A Navajo infant spends 60 to 70 percent of its time o n a cradle board for the first six months of life. Cradle boards were formerly a lso common practice in Europe but began to disappear there a few centuries ago. To many of us moderns, the idea of a cradle board or swaddling is abhorrent or was , until swaddling recently came back into vogue. The notion of personal freedom means a lot to us, and a cradle board or swaddling undoubtedly does restrict an infant s personal freedom. We are prone to assume that cradle boards or swaddling retard a child s development and inflict lasting psychological damage. In fact, th ere are no personality or motor differences, or differences in age of independen

t walking, between Navajo children who were or were not kept on a cradle board, or between cradle-boarded Navajo children and nearby Anglo-American children. The probable explanation is that, by the age that an infant starts to crawl, the inf ant is spending half of its day off of the cradle board anyway, and most of the time that it spends on the cradle board is when the infant is asleep. Hence it i s argued that doing away with cradle boards brings no real advantages in freedom , stimulation, or neuromotor development. Typical Western children sleeping in s eparate rooms, transported in baby carriages, and left in cribs during the day a re often socially more isolated than are cradle-boarded Navajo children. There has been a long debate among pediatricians and child psychologists about h ow best to respond to a child s crying. Of course, the parent first checks whether the child is in pain or really needs some help. But if there seems to be nothin g wrong, is it better to hold and comfort a crying child, or should one put down the child and let it cry until it stops, however long that takes? Does the chil d cry more if its parents put the child down and walk out of the room, or if the y continue to hold it? Observers of children in hunter-gatherer societies commonly report that, if an in fant begins crying, the parents practice is to respond immediately. For example, if an Efe Pygmy infant starts to fuss, the mother or some other caregiver tries to comfort the infant within 10 seconds. If a !Kung infant cries, 88 percent of crying bouts receive a response within 3 seconds, and almost all bouts receive a response within 10 seconds. Mothers respond to !Kung infants by nursing them, b ut many responses are by nonmothers (especially other adult women), who react by touching or holding the infant. The result is that !Kung infants spend at most one minute out of each hour crying, mainly in crying bouts of less than 10 secon ds half that measured for Dutch infants. Many other studies show that 1-year-old i nfants whose crying is ignored end up spending more time crying than do infants whose crying receives a response. Share the Parenting What about the child-rearing contribution of caregivers other than the mother an d the father? In modern Western society, a child s parents are typically by far it s dominant caregivers. The role of allo-parents i.e., individuals who are not the bi ological parents but who do some caregiving has even been decreasing in recent dec ades, as families move more often and over longer distances, and children no lon ger have the former constant availability of grandparents and aunts and uncles l iving nearby. This is of course not to deny that babysitters, schoolteachers, gr andparents, and older siblings may also be significant caregivers and influences . But allo-parenting is much more important, and parents play a less dominant ro le, in traditional societies. In hunter-gatherer bands the allo-parenting begins within the first hour after bi rth. Newborn Aka and Efe infants are passed from hand to hand around the campfir e, from one adult or older child to another, to be kissed, bounced, and sung to and spoken to in words that they cannot possibly understand. Anthropologists hav e even measured the average frequency with which infants are passed around: it a verages eight times per hour for Efe and Aka Pygmy infants. Hunter-gatherer moth ers share care of infants with fathers and allo-parents, including grandparents, aunts, great-aunts, other adults, and older siblings. Again, this has been quan tified by anthropologists, who have measured the average number of care-givers: 14 for a 4-month-old Efe infant, seven or eight for an Aka infant, over the cour se of an observation period of several hours. Daniel Everett, who lived for many years among the Piraha Indians of Brazil, com mented, The biggest difference [of a Piraha child s life from an American child s lif e] is that Piraha children roam about the village and are considered to be relat ed to and partially the responsibility of everyone in the village. Yora Indian ch ildren of Peru take nearly half of their meals with families other than their ow

n parents. The son of American missionary friends of mine, after growing up in a small New Guinea village where he considered all adults as his aunts or uncles, nd the relative lack of allo-parenting a big shock when his parents brought him back to the United States for high school. In small-scale societies, the allo-parents are materially important as additional providers of food and protection. Hence studies around the world agree in showi ng that the presence of allo-parents improves a child s chances for survival. But allo-parents are also psychologically important, as additional social influences and models beyond the parents themselves. Anthropologists working with small-sc ale societies often comment on what strikes them as the precocious development o f social skills among children in those societies, and they speculate that the r ichness of allo-parental relationships may provide part of the explanation. Similar benefits of allo-parenting operate in industrial societies as well. Soci al workers in the United States note that children gain from living in extended, multigenerational families that provide allo-parenting. Babies of unmarried low -income American teenagers, who may be inexperienced or neglectful as mothers, d evelop faster and acquire more cognitive skills if a grandmother or older siblin g is present, or even if a trained college student just makes regular visits to play with the baby. The multiple caregivers in an Israeli kibbutz or in a qualit y day-care center serve the same function. I have heard many anecdotal stories, among my own friends, of children who were raised by difficult parents but who n evertheless became socially and cognitively competent adults, and who told me th at what had saved their sanity was regular contact with a supportive adult other than their parents, even if that adult was just a piano teacher whom they saw o nce a week for a piano lesson. Give Them More Freedom How much freedom or encouragement do children have to explore their environment? Are children permitted to do dangerous things, with the expectation that they m ust learn from their mistakes? Or are parents protective of their children s safet y, and do parents curtail exploration and pull kids away if they start to do som ething that could be dangerous? The answer to this question varies among societies. However, a tentative general ization is that individual autonomy, even of children, is a more cherished ideal in hunter-gatherer bands than in state societies, where the state considers tha t it has an interest in its children, does not want children to get hurt by doin g as they please, and forbids parents to let a child harm itself. That theme of autonomy has been emphasized by observers of many hunter-gatherer societies. For example, Aka Pygmy children have access to the same resources as do adults, whereas in the U.S. there are many adults-only resources that are off -limits to kids, such as weapons, alcohol, and breakable objects. Among the Mart u people of the Western Australian desert, the worst offense is to impose on a c hild s will, even if the child is only 3 years old. The Piraha Indians consider ch ildren just as human beings, not in need of coddling or special protection. In E verett s words, They [Piraha children] are treated fairly and allowance is made for their size and relative physical weakness, but by and large they are not consid ered qualitatively different from adults ... This style of parenting has the res ult of producing very tough and resilient adults who do not believe that anyone owes them anything. Citizens of the Piraha nation know that each day s survival de pends on their individual skills and hardiness ... Eventually they learn that it is in their best interests to listen to their parents a bit. Some hunter-gatherer and small-scale farming societies don t intervene when childr en or even infants are doing dangerous things that may in fact harm them, and th at could expose a Western parent to criminal prosecution. I mentioned earlier my surprise, in the New Guinea Highlands, to learn that the fire scars borne by so many adults of Enu s adoptive tribe were often acquired in infancy, when an infan t was playing next to a fire, and its parents considered that child autonomy ext ended to a baby s having the right to touch or get close to the fire and to suffer the consequences. Hadza infants are permitted to grasp and suck on sharp knives

fou

. Nevertheless, not all small-scale societies permit children to explore freely and do dangerous things. The World Until Yesterday: What Can We Learn from Traditional Societies? by Jared Diamond. 512 p. Viking Adult. $22.94 On the American frontier, where pop?ulation was sparse, the one-room schoolhouse was a common phenomenon. With so few children living within daily travel distan ce, schools could afford only a single room and a single teacher, and all childr en of different ages had to be educated together in that one room. But the one-r oom schoolhouse in the U.S. today is a romantic memory of the past, except in ru ral areas of low population density. Instead, in all cities, and in rural areas of moderate population density, children learn and play in age cohorts. School c lassrooms are age-graded, such that most classmates are within a year of each ot her in age. While neighborhood playgroups are not so strictly age-segregated, in densely populated areas of large societies there are enough children living wit hin walking distance of each other that 12-year-olds don t routinely play with 3-y ear-olds. But demographic realities produce a different result in small-scale societies, w hich resemble one-room schoolhouses. A typical hunter-gatherer band numbering ar ound 30 people will on the average contain only about a dozen preadolescent kids , of both sexes and various ages. Hence it is impossible to assemble separate ag e-cohort playgroups, each with many children, as is characteristic of large soci eties. Instead, all children in the band form a single multi-age playgroup of bo th sexes. That observation applies to all small-scale hunter-gatherer societies that have been studied. In such multi-age playgroups, both the older and the you nger children gain from being together. The young children gain from being socia lized not only by adults but also by older children, while the older children ac quire experience in caring for younger children. That experience gained by older children contributes to explaining how hunter-gatherers can become confident pa rents already as teenagers. While Western societies have plenty of teenage paren ts, especially unwed teenagers, Western teenagers are suboptimal parents because of inexperience. However, in a small-scale society, the teenagers who become pa rents will already have been taking care of children for many years. Another phenomenon affected by multi-age playgroups is premarital sex, which is reported from all well-studied small hunter-gatherer societies. Most large socie ties consider some activities as suitable for boys, and other activities as suit able for girls. They encourage boys and girls to play separately, and there are enough boys and girls to form single-sex playgroups. But that s impossible in a ba nd where there are only a dozen children of all ages. Because hunter-gatherer ch ildren sleep with their parents, either in the same bed or in the same hut, ther e is no privacy. Children see their parents having sex. In the Trobriand Islands , one researcher was told that parents took no special precautions to prevent th eir children from watching them having sex: they just scolded the child and told it to cover its head with a mat. Once children are old enough to join playgroup s of other children, they make up games imitating the various adult activities t hat they see, so of course they have sex games, simulating intercourse. Either the adults don t interfere with child sex play at all, or else !Kung parent s discourage it when it becomes obvious, but they consider child sexual experime ntation inevitable and normal. It s what the !Kung parents themselves did as child ren, and the children are often playing out of sight where the parents don t see t heir sex games. Many societies, such as the Siriono and Piraha and New Guinea Ea stern Highlanders, tolerate open sexual play between adults and children. What We Can Learn Let s reflect on differences in child-rearing practices between small-scale societ ies and state societies. Of course, there is much variation among industrial sta te societies today in the modern world. Ideals and practices of raising children

differ between the U.S., Germany, Sweden, Japan, and an Israeli kibbutz. Within any given one of those state societies, there are differences between farmers, urban poor people, and the urban middle class and differences from generation to generation within a society. Nevertheless, there are still some basic similarities among all of those state s ocieties, and some basic differences between state and nonstate societies. State governments have their own separate interests regarding the state s children, and those interests do not necessarily coincide with the interests of a child s paren ts. Small-scale nonstate societies also have their own interests, but a state so ciety s interests are more explicit, administered by more centralized top-down lea dership, and backed up by well-defined enforcing powers. All states want childre n who, as adults, will become useful and obedient citizens, soldiers, and worker s. States tend to object to having their future citizens killed at birth, or per mitted to become burned by fires. States also tend to have views about the educa tion of their future citizens, and about their citizens sexual conduct. Naturally, I m not saying that we should emulate all child-rearing practices of hu nter-gatherers. I don t recommend that we return to the hunter-gatherer practices of selective infanticide, high risk of death in childbirth, and letting infants play with knives and get burned by fires. Some other features of hunter-gatherer childhoods, like the permissiveness of child sex play, feel uncomfortable to ma ny of us, even though it may be hard to demonstrate that they really are harmful to children. Still other practices are now adopted by some citizens of state so cieties, but make others of us uncomfortable such as having infants sleep in the sa me bedroom or in the same bed as parents, nursing children until age 3 or 4, and avoiding physical punishment of children. But some other hunter-gatherer child-rearing practices may fit readily into mode rn state societies. It s perfectly feasible for us to transport our infants vertic ally upright and facing forward, rather than horizontally in a pram or verticall y but facing backward in a pack. We could respond quickly and consistently to an infant s crying, practice much more extensive allo-parenting, and have far more p hysical contact between infants and caregivers. We could encourage self-invented play of children, rather than discourage it by constantly providing complicated so-called educational toys. We could arrange for multi-age child playgroups, rat her than playgroups consisting of a uniform age cohort. We could maximize a chil d s freedom to explore, insofar as it is safe to do so. But our impressions of greater adult security, autonomy, and social skills in sm all-scale societies are just impressions: they are hard to measure and to prove. Even if these impressions are real, it s difficult to establish that they are the result of a long nursing period, allo-parenting, and so on. At minimum, though, one can say that hunter-gatherer rearing practices that seem so foreign to us ar en t disastrous, and they don t produce societies of obvious sociopaths. Instead, th ey produce individuals capable of coping with big challenges and dangers while s till enjoying their lives. The hunter-gatherer lifestyle worked at least tolerab ly well for the nearly 100,000-year history of behaviorally modern humans. Every body in the world was a hunter-gatherer until the local origins of agriculture a round 11,000 years ago, and nobody in the world lived under a state government u ntil 5,400 years ago. The lessons from all those experiments in child-rearing th at lasted ?for such a long time are worth considering seriously. From The World Until Yesterday by Jared Diamond. Reprinted by arrangement with V iking, a member of Penguin Group (USA), Inc. Copyright 2012 by Jared Diamond.

http://www.thedailybeast.com/newsweek/2012/12/16/best-practices-for-raising-kids -look-to-hunter-gatherers.html

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------Comments Primrose This is a daily beast article not a peer reviewed article so I get that some thi ns are missing. I don't really appreciate that he lumps the Navajo with the Kung as the Navajo are not hunter gatherers. They are farmers. And of course we al l had more freedom, much closer these children described than children do today because there were always adults around to run to. I do think this obsessive nee d to make babies self-reliant is a sickness. They are babies. They need their ne eds met to become secure adults. morgan we could learn a lot from other cultures if only we could drop our "we're #1" at titude. in japan the children are walking to school in groups of 5-15 from a ve ry early age - 5, they walk for sometimes 20 minutes, there is no parent to acco mpany them, and if it rains they get wet. no one there would think of taking the ir children in the car just for those reasons. a good friend lives in a large bu t relatively isolated city on japan and her children have taken the train to the downtown area on their own for years. they are now in their early teens. we here in the US are really doing our children a disservice by jumping into squ abbles with friends, intervening with coaches when our kids are not happy about playing time, and meeting with teachers beyond elementary school regarding our k ids' grades. a friend of mine has gone to her high school senior's teachers abou t grades, been a chaperone at high school events such as the prom, etc. living life vicariously through our children has never been a good idea and it's only getting worse for some parents. those of us who have allowed our children to make their own decisions within reason from an early age have done the most b eneficial thing for our kids. for example, there is nothing wrong with starting early by letting your child choose his own clothes for himself. my son began doi ng this when he was 2.......he chose from clothes i laid out the night before an d he was never told 'you can't wear that.' Kalyie Prof. Diamond makes many great points in this article. He is certainly not roman ticizing these societies, but merely pointing out that we can learn some things from them. I agree that we greatly value our advanced technology, medicine, engi neering, etc. and wouldn't trade it for their primitive lifestyle. However, one look at how many kids today have been diagnosed with mental disorders/conditions makes me a bit worried. Not that it's necessarily wrong to do so, but oftentime s this results in over-protection/coddling and/or isolation from mainstream soci ety. I like how the hunter-gatherer societies in this article treat children no different than adults for the most part and encourage their independence as such . Who's to say none of these children have mental disorders if they were sent to the U.S. and psychologically tested? But even if they did, they'd have learned to overcome it themselves. Living in their community, they'd have that innate de sire to WANT to become a part of society, rather than shrink into a narrow "fant asy" world of online porn and violent video games. And it goes both ways as well : the community would WANT and ENCOURAGE them to become part of the community, r ather than focusing on how they might be different and coming up with complicate d tests to prove such hypotheses. While we can argue that such tests enable our children to get "special attention and care," who's to say it doesn't have the o pposite effect of pushing these children farther and farther away from the regul

ar functional society? They will gradually think of themselves as "different," a nd so will everyone else around them. Segregation, whether intentional or not, c an't be good for children who need to interact with all types of people in a non -judgmental environment to grow into confident and responsible adults. Wallysmom Sure, overparenting is a real problem in the US. Insecure, hesitant, unsure and untested young adults are the result. However, I can believe that in the society that allows their children to suck on knives, there are a lot of young adults w ithout tongues. (Which ironically, for anyone who has raised a teenager, is not a bad thing.) conversated Procreation: A Right or a Privilege?

Honeyweed The trouble is that in the U.S. we may use the term over-parenting to apply both t o attachment parenting years of nursing, holding, sleeping close and to helicopter parenting over-directing the childs actions and not letting them risk danger or fa ilure. But the traditional societies Diamond is talking about show that these tw o things are very different and shouldnt be lumped together. Hunter-gatherers def initely practice attachment, but they dont hover over their children. I agree with Diamond that we should learn from them. Early physical attachment, quick respons e to cries, etc. doesnt turn out to correlate with later dependence in children, but actually produces independence. XiraArien666 It's a shame that none of this is at all legal in modern Amerika, or we could ra ise self-reliant children who don't think anyone owes them anything. Try it tod ay, and you'll end up in jail real fast. jeffc How are allo-parenting or multi-age play groups illegal? Having your infant slee p in the same room or bed isn't illegal, just frowned upon.Luckily for you being hyperbolic isn't illegal either, even though it posses a great threat to our co untry. AndrewKamadulski How many great works of literature were created by these tribes? How many cures for new diseases? How many moon missions? Yeah. Let's pattern our society after these people. That makes sense. Sinan I would ask you to strip naked and walk into the Darien jungle and live on your wits. My bet is you wouldn't last a week. Honeyweed It's interesting, Diamond wrote a book on why he thinks some societies are more 'developed' then others, it's quite interesting. On another note, you're judging them by your own standard of what's good. I'm su re many of those people would think working 40+ hours a week for things you don' t want to impress people you don't like while living in the middle of a civiliza

tion that is polluted and wasteful by most definitions makes YOU the idiot. AndrewKamadulski Except for one little problem chief. I work at what I love and I do it because I love it. If there was anything in the world I could choose to do, it would be what I do now because it completes me. Nice to see that you are judging by your preconceived notions of me instead of reality. I'd say that makes YOU the idiot. APinq Judge societies by the standards of your own culture, and -- what a surprise! -yours tends to come out on top. What a coincidence, huh? Do you think these p eople particularly value moon missions? Do you think they don't have their own stories and artistic traditions which are of much greater value and interest to them than our literature? As for "cures for new diseases," most "new diseases" come about as a product of our "advanced" lifestyle and environment -- if these people have need for such "cures" it's as a result of contact with the so-called modern world. You have learned to think the world you inhabit offers you the b est life and possibilities; they by and large believe the same of theirs. Neith er is incorrect, because, as was the point of this whole article, there are thin gs to value about each. But reckoning your own viewpoint to happen to be object ively superior is comically stupid and small-minded. BarbaraPiper Your website refers to Jared Diamond as a "Pulitzer Prize winning anthropologist ." He is not an anthropologist, and professional anthropologists have widely cri ticized his work as naive and simplistic. Falcon @BarbaraPiper Cheap shot. Diamond obtained a PhD in physiology and has never cla imed otherwise, although he's expanded his career into such areas as evolutionar y biology and biogeography. Some anthropologists may have criticized him (and I' m sure that professional jealousy has nothing to do with it) because, of course, anyone who writes for the general public must be "naive". BarbaraPiper @Falcon86 @BarbaraPiper I never said he made such a claim -- it was Newsweek's description, and it is wrong. Motives for criticizing him are not relevant; the specific criticisms are, and they are valid and extensive. Labels of expertise a re a form of intellectual currency, and Newsweek inflates the value of Diamond's currency when it calls him an anthropologist.

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- We Need An Intellectual AwakeningDokumen6 halamanWe Need An Intellectual Awakeningddiver1Belum ada peringkat

- PG 39402Dokumen175 halamanPG 39402ddiver1Belum ada peringkat

- Muslim Bias in Texas SchoolsDokumen1 halamanMuslim Bias in Texas Schoolsddiver1Belum ada peringkat

- Ending Science As We Know ItDokumen15 halamanEnding Science As We Know Itddiver1Belum ada peringkat

- Dynamic EquivalencyDokumen92 halamanDynamic Equivalencyddiver1Belum ada peringkat

- Why Not Artificial WombsDokumen10 halamanWhy Not Artificial Wombsddiver1Belum ada peringkat

- The Eccentric Monk and His TypewriterDokumen3 halamanThe Eccentric Monk and His Typewriterddiver1Belum ada peringkat

- Older Parenthood Will Upend American SocietyDokumen12 halamanOlder Parenthood Will Upend American Societyddiver1Belum ada peringkat

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (587)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (399)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (73)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5794)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2219)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (344)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (265)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)

- Orphanage ReflectionDokumen4 halamanOrphanage Reflectionapi-2728460910% (1)

- Toxic ChildhoodDokumen6 halamanToxic ChildhoodCourtney Green100% (1)

- Peranan Orang Tua Dalam Mencegah Tawuran Antar Pelajar Fatma Tresno IngtyasDokumen13 halamanPeranan Orang Tua Dalam Mencegah Tawuran Antar Pelajar Fatma Tresno IngtyasZeforBelum ada peringkat

- A Study About Autism Autistic DisorderDokumen6 halamanA Study About Autism Autistic DisorderJamaica QuetuaBelum ada peringkat

- MCHATDokumen2 halamanMCHATPramita SariBelum ada peringkat

- Literature Review - DemarcoDokumen7 halamanLiterature Review - Demarcoapi-582867127Belum ada peringkat

- Maternal and Infant Risk Factors Associated with Neonatal Asphyxia in BaliDokumen6 halamanMaternal and Infant Risk Factors Associated with Neonatal Asphyxia in BaliNisa UcilBelum ada peringkat

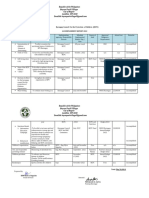

- BCPC 2022 Accomplishment ReportDokumen2 halamanBCPC 2022 Accomplishment ReportBpv Barangay100% (8)

- Syllabus B.Ed. - Two Year Course - 2015 2017 PDFDokumen84 halamanSyllabus B.Ed. - Two Year Course - 2015 2017 PDFRahul SinghBelum ada peringkat

- Makalah Hasil Abdimas - Amanda YangDokumen9 halamanMakalah Hasil Abdimas - Amanda YangamandaBelum ada peringkat

- RRLDokumen2 halamanRRLKim Charlotte Balicat-Rojo ManzoriBelum ada peringkat

- Evaluation of Bowlby's TheoryDokumen1 halamanEvaluation of Bowlby's TheorymiddleswithbooksBelum ada peringkat

- Care To Be Aware: " A Single Pleasure Is Not Worth Your Future." A Campaign Awareness For Pre-Marital Sex and Early PregnanciesDokumen3 halamanCare To Be Aware: " A Single Pleasure Is Not Worth Your Future." A Campaign Awareness For Pre-Marital Sex and Early PregnanciesMariella Rose BenitoBelum ada peringkat

- Harry HarlowDokumen7 halamanHarry Harlowapi-254294944Belum ada peringkat

- BCPCDokumen2 halamanBCPCmichael ricafort100% (1)

- Abuse of Parents to ChildrenDokumen4 halamanAbuse of Parents to ChildrenJonathan Espina EjercitoBelum ada peringkat

- Barrocas ThesisfinalDokumen29 halamanBarrocas Thesisfinalinetwork200180% (10)

- ReferenceDokumen6 halamanReferenceprincess anneBelum ada peringkat

- Lesson 38 Science Life Cycle of HumanDokumen19 halamanLesson 38 Science Life Cycle of HumanMisha Madeleine GacadBelum ada peringkat

- 1 - BCPCDokumen2 halaman1 - BCPCsan nicolas 2nd betis guagua pampangaBelum ada peringkat

- Child Culture - Play Culture PDFDokumen36 halamanChild Culture - Play Culture PDFCaren AlbuquerqueBelum ada peringkat

- Essential Newborn CareDokumen15 halamanEssential Newborn CareBilly James PlazaBelum ada peringkat

- The Impact of Separation and Loss on Child DevelopmentDokumen10 halamanThe Impact of Separation and Loss on Child DevelopmentŞterbeţ RuxandraBelum ada peringkat

- Argumentative EssayDokumen5 halamanArgumentative Essayapi-33103223333% (3)

- The Formative Years: MODULE 14: Socio-Emotional Development of Infants and ToddlersDokumen4 halamanThe Formative Years: MODULE 14: Socio-Emotional Development of Infants and ToddlersShaira DumagatBelum ada peringkat

- Persuasive Outline - Teen PregnancyDokumen3 halamanPersuasive Outline - Teen PregnancyMichelle50% (4)

- IYCF Counselling OverviewDokumen35 halamanIYCF Counselling Overviewgeline joyBelum ada peringkat

- Request Form 1Dokumen12 halamanRequest Form 1Mary Marbas Maglangit AlmonteBelum ada peringkat

- Omnibus Designation Coordinatorship 2022 2023Dokumen2 halamanOmnibus Designation Coordinatorship 2022 2023Gigi Quinsay VisperasBelum ada peringkat

- 44 ThievesDokumen3 halaman44 Thievesmimilini09Belum ada peringkat