Economy: Two Approaches To Market Equilibrium

Diunggah oleh

Farhat Abbas DurraniDeskripsi Asli:

Judul Asli

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Economy: Two Approaches To Market Equilibrium

Diunggah oleh

Farhat Abbas DurraniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Economy

An economy consists of the economic system of a country or other area, the labour, capital and land resources, and the economic agents that socially participate in the production, exchange, distribution, and consumption of goods and services of that area. A given economy is the end result of a process that involves its technological evolution, history and social organization, as well as its geography, natural resource endowment, and ecology, as main factors. These factors give context, content, and set the conditions and parameters in which an economy functions. Today the range of fields of study examining the economy include social sciences such as economics, sociology (economic sociology), history (economic history),anthropology (economic anthropology), and geography (economic geography). Practical fields directly related to the human activities involving production, distribution, exchange, and consumption of goods and services as a whole, range from engineering to management and business administration to applied science to finance. All professions, occupations, economic agents or economic activities, contribute to the economy. Consumption, saving, and investment are core variable components in the economy and determine market equilibrium. There are three main sectors of economic activity: primary, secondary, and tertiary.

Two Approaches to Market Equilibrium

The Graphical Approach

By now, we are familiar with graphs of supply curves and demand curves. To find market equilibrium, we combine the two curves onto one graph. The point of intersection of supply and demand marks the point of equilibrium. Unless interfered with, the market will settle at this price and quantity. Why is this? At this point of intersection, buyers and sellers agree on both price and quantity. For instance, in the graph below, we see that at the equilibrium price p*, buyers want to buy exactly the same amount that sellers want to sell.

Figure %: Market Equilibrium If the price were higher, however, we can see that sellers would want to sell more than buyers would want to buy. Likewise, if the price were lower, quantity demanded would be greater than

quantity supplied. The following graph shows the discrepancy in supply and demand if the price is higher than the equilibrium price:

Figure %: Price Higher than Equilibrium Price Note that the quantity that sellers are willing to sell is much higher than the quantity that buyers are willing to buy.

We can also see what happens when one of the curves shifts up or down in response to outside factors. For example, if we were to look at the market for Beanie Babies before and after they became a popular fad, we would see a shift outwards from the initial demand curve over time. The reason for this is that as people began to like Beanie Babies, their preferences changed, and they began to want Beanie Babies enough that they would pay much more for each Beanie Baby than they would have previously. We can see this new preference for Beanie Babies in the outward shift of the demand curve: for every price, buyers will buy more Beanie Babies than they would have before the fad.

Figure %: Shift in the Demand for Beanie Babies Note that this combines two effects we studied earlier: there is a shift in the demand curve, which causes a movement up the supply curve. These two effects combine to reach the new market equilibrium, which has both a higher price and a higher quantity than the previous market equilibrium. It is only through a shift in either the supply or the demand curve that the market equilibrium will change. Why is this? If neither curve shifts, and we move along one of the curves, the market will naturally shift back to equilibrium. For example, if we look at a market in equilibrium, and a store

tries to move up its supply curve by selling goods at a higher price, the result will be that no one will buy the goods, since they are less expensive at the store's competitors. The store will have to either go out of business, or move its prices back down to equilibrium. What happens if both curves shift? Will we end up at the same equilibrium point? In this model, it is not possible to reach the same equilibrium: either the price or the quantity can be the same as the previous equilibrium, but not both, unless the curves shift back to their original positions. To illustrate why this is true, consider the graph below. The initial equilibrium, between supply curve 1 and demand curve 1, has price p* and quantity q*. If supply shifts to supply curve 2, both equilibrium price and quantity change. It is now possible to change back to our original price by shifting the demand curve to position 2 or it is possible to revert to our original quantity by shifting the demand curve to position 3. Note that we cannot reach the original equilibrium point unless we move the curves back to their original points.

Figure %: Shift in Supply and Demand For a real world example, consider the market for oil. The initial supply and demand curves would be at position 1 (p1). When the suppliers decide to collaborate and supply less oil for every price, this causes a backwards shift in the supply curve, to supply curve 2. This cuts the quantity supplied from quantity 1 (q1) to quantity 2 (q2) and raises the price paid for oil along demand curve 1. We can either shift the demand curve in to curve 2, maintaining previous price levels, but decreasing consumption even more, or we can shift our demand curve out to curve 3, maintaining previous levels of consumption but raising prices. Since there is a tradeoff between having steady prices or steady consumption, the consumers have to make a decision about which is more important to them. In the short run, they will probably decide to pay the higher prices to keep consumption steady (that is, they will shift out to curve 3), but if the prices stay high for a long time, they will start finding ways to economize, (thereby shifting in to curve 2).

The Algebraic Approach

We have worked with supply and demand equations separately, but they can also be combined to find market equilibrium. We have already established that at equilibrium, there is one price, and one quantity, on which both the buyers and the sellers agree. Graphically, we see that as a single intersection of two curves. Mathematically, we will see it as the result of setting the two equations equal in order to find equilibrium price and quantity. If we are looking at the market for cans of paint, for instance, and we know that the supply equation is as follows: QS = -5 + 2P

And the demand equation is: QD = 10 - P Then to find the equilibrium point, we set the two equations equal. Notice that quantity is on the left-hand side of both equations. Because quantity supplied is equal to quantity demanded at equilibrium, we can set the right-hand sides of the two equations equal. QS = QD -5 + 2P = 10 - P 3P = 15 P=5 At equilibrium, paint will cost $5 a can. To find out the equilibrium quantity, we can just plug the equilibrium price into either equation and solve for Q. Q* = QS QS = -5 + 2(5) QS = Q* = 5 cans

Shifts up and down supply and demand curves are represented by plugging different prices into the supply and demand equations: different prices yield different quantities. For example, changing the price to $6 a can would decrease quantity demanded from 5 cans to 4 cans, as we can see when we plug the two prices into the demand function: P=5 QD = 10 - 5 = 5 cans P=6 QD = 10 - 6 = 4 cans The equivalent of shifting supply and demand curves is changing the actual supply and demand equations. Let's say that everyone in a small town just recently painted their houses, and therefore no longer need any paint. This means that they will be less willing to buy paint, even if the price doesn't go up. Their new demand function might be: QD = 7 - P We can see that for any price, they will demand fewer cans of paint. At the old equilibrium price of $5, they will only buy: QD = 7 - 5 = 2 cans of paint This new equation, representing a shift in demand, also causes a shift in market equilibrium, which we can find by setting the new demand equation equal to supply: QS = QD -5 + 2P = 7 - P 3P = 12 P = $4 a can Now to solve for the equilibrium quantity: Q* = QS QS = -5 + 2P = -5 + 2(4) QS = Q* = 3 cans of paint At the new equilibrium, 3 cans of paint will be sold at $4 each.

Government Intervention with Markets

Theoretically, if left alone, a market will naturally settle into equilibrium: the equilibrium price ensures that all sellers who are willing to sell at that price, and all buyers who are willing to buy at that price will get what they want. At equilibrium, supply is exactly equal to demand. However, in some cases, the government will interfere with the market, putting in price ceilings or price floors, charging taxes, or using other measures to reshape the economy.

Price Ceilings

A price ceiling is an upper limit for the price of a good: once a price ceiling has been put in, sellers cannot charge more than that. In most cases, price ceilings are below market price. If a price ceiling is set at or above market price, there will be no noticeable effect, and the ceiling is only a preventative measure. If the ceiling is set below market price, however, there will be a shortage of goods. For instance, if the government thinks 1) that people need bread to live, and 2) that the market price of bread is too high, then they might install a price ceiling. Assume that the following graph represents the market for bread. At equilibrium, the price will be p*, and the quantity will be q*.

Figure %: Price Ceiling If the government puts in a price ceiling, we can see that the quantity demanded will exceed the quantity supplied, meaning that not enough bread will be supplied to satisfy demand. Such a situation is called a shortage. Because price ceilings are installed in the interests of the buyers, the government has to decide which situation is preferable for the buyers: not being able to afford any bread, or not having enough bread to go around.

Price Floors

The opposite of a price ceiling is a price floor. A price floor is an artificially introduced minimum for the price of a good. In most cases, the price floor is above the market price. Price floors are usually put in to benefit sellers. For example, price floors are sometimes used for agricultural products. The market price can sometimes be so low that farmers cannot make enough money to support themselves. In such cases, the government steps in and sets a price floor, which can cause problems of its own:

Figure %: Price Floor Notice that when the price is artificially raised above p*, the quantity supplied exceeds the quantity demanded. Such a situation is called a surplus: farmers produce many more crops than buyers want to buy at the new, higher price.

Taxes

Another way in which the government can alter the market is through taxes. One such example is in the tobacco market: if the government would like to discourage the sale and use of tobacco, they would charge tobacco sellers a tax on tobacco products. In most cases, sellers pass as much of the added cost on to buyers as possible. Because the sellers don't want to lose any profits, they have to increase their selling price in order to maintain the same profit margin, since they had to pay an extra tax when obtaining the products for resale. In such cases, the supply curve will shift vertically by the exact amount of the tax. So, if the government charges a $1 tax on every pack of cigarettes, and the cigarette sellers want to pass this tax on to the buyers, then the supply curve will shift upwards by $1. (Note that the $1 shift is the vertical distance between the pre-tax and post-tax curves). The net result is that for any price, the stores will sell fewer packs of cigarettes, to make up for the extra cost of the tax. In effect, if consumers want to maintain their previous levels of consumption, cigarettes would now cost $1 more per pack. However, the new equilibrium shows that prices will be in between p and (p+1), and the new quantity will be less than the initial quantity. We can see how this works on the graph below.

Figure %: Change in Equilibrium Due to Tax

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- Economics for CFA level 1 in just one week: CFA level 1, #4Dari EverandEconomics for CFA level 1 in just one week: CFA level 1, #4Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (2)

- CMA Part 1A MircoeconomicsDokumen54 halamanCMA Part 1A Mircoeconomicsmah800100% (3)

- Unit III Supply Chain DriversDokumen13 halamanUnit III Supply Chain Driversraazoo19Belum ada peringkat

- A level Economics Revision: Cheeky Revision ShortcutsDari EverandA level Economics Revision: Cheeky Revision ShortcutsPenilaian: 3 dari 5 bintang3/5 (1)

- Supply and Demand NotesDokumen8 halamanSupply and Demand NotesFaisal Hameed100% (2)

- Study Guide Mid Term International EconomicsDokumen16 halamanStudy Guide Mid Term International EconomicsArturo QuiñonesBelum ada peringkat

- Principles of Micro EconomicsDokumen275 halamanPrinciples of Micro Economicsashairways67% (3)

- Lecture Notes Applied Mathematics For Business, Economics, and The Social Sciences (4th Edition) by Budnick PDFDokumen171 halamanLecture Notes Applied Mathematics For Business, Economics, and The Social Sciences (4th Edition) by Budnick PDFRizwan Malik100% (5)

- Xam Idea EconomicsDokumen370 halamanXam Idea EconomicsCarl LukeBelum ada peringkat

- The Theory of Monetary InstitutionsDokumen286 halamanThe Theory of Monetary InstitutionsErnesto Sastre100% (3)

- Supply and DemandDokumen7 halamanSupply and DemandManoj K100% (1)

- Chapter 2 Demand and SupplyDokumen34 halamanChapter 2 Demand and SupplyAbdul-Mumin AlhassanBelum ada peringkat

- 2.4 Market Equilibrium ExerciseDokumen13 halaman2.4 Market Equilibrium ExercisePersephone RoseBelum ada peringkat

- Grain Preservation BiosystemDokumen429 halamanGrain Preservation BiosystemBufalo GennaroBelum ada peringkat

- Market EquilibriumDokumen38 halamanMarket EquilibriumAbhi KumBelum ada peringkat

- Applied EconomicsDokumen42 halamanApplied EconomicsAngeline RegatonBelum ada peringkat

- Health Economics SupplyDokumen7 halamanHealth Economics SupplyPao C EspiBelum ada peringkat

- Google Market Equilibrium ExamplesDokumen11 halamanGoogle Market Equilibrium ExamplesAllicamet SumayaBelum ada peringkat

- Basic Economic Concepts and TerminologyDokumen11 halamanBasic Economic Concepts and TerminologyAbdul QuorishyBelum ada peringkat

- Unit 3 (QBA)Dokumen7 halamanUnit 3 (QBA)Mashi MashiBelum ada peringkat

- LESSON 3 - Demand and SupplyDokumen6 halamanLESSON 3 - Demand and SupplyChirag HablaniBelum ada peringkat

- Demand & SupplyDokumen13 halamanDemand & SupplyMeenakshi AnandBelum ada peringkat

- Managerial Econ LessonDokumen14 halamanManagerial Econ LessonKarysse Arielle Noel JalaoBelum ada peringkat

- Market Equilibrium PriceDokumen15 halamanMarket Equilibrium Pricevinu50% (2)

- Module 2 in MacroeconomicsDokumen7 halamanModule 2 in MacroeconomicsIvan CasTilloBelum ada peringkat

- Team Yey ReportingDokumen21 halamanTeam Yey Reportinglladera631Belum ada peringkat

- Law of Supply and DemandDokumen49 halamanLaw of Supply and DemandArvi Kyle Grospe PunzalanBelum ada peringkat

- 2 4 Market Equilibrium ExerciseDokumen13 halaman2 4 Market Equilibrium ExerciseAditri PatilBelum ada peringkat

- Chapter 2 - SummaryDokumen15 halamanChapter 2 - SummaryPrerna BansalBelum ada peringkat

- EconomicsDokumen11 halamanEconomics41Sudipta BeraBelum ada peringkat

- Demand and Supply MicroeconomicsDokumen13 halamanDemand and Supply Microeconomicsआस्तिक शर्माBelum ada peringkat

- Supply and Demand and Market EquilibriumDokumen10 halamanSupply and Demand and Market EquilibriumMerliza JusayanBelum ada peringkat

- Supply and DemandaDokumen15 halamanSupply and DemandaJoshue SandovalBelum ada peringkat

- Ae Week 5 6 PDFDokumen26 halamanAe Week 5 6 PDFmary jane garcinesBelum ada peringkat

- Tips and Samples CH 3 Demand and SupplyDokumen17 halamanTips and Samples CH 3 Demand and Supplytariku1234Belum ada peringkat

- Basic Microeconomics: Session Topic: Basic Analysis of Demand and SupplyDokumen16 halamanBasic Microeconomics: Session Topic: Basic Analysis of Demand and SupplyMaxine RubiaBelum ada peringkat

- AssignmentDokumen53 halamanAssignmentSamyuktha SaminathanBelum ada peringkat

- CH 2Dokumen10 halamanCH 2ende workuBelum ada peringkat

- Summary MacroDokumen64 halamanSummary Macrojayesh.guptaBelum ada peringkat

- Demand TheoryDokumen10 halamanDemand TheoryVinod KumarBelum ada peringkat

- Plugin LawofMarketsDokumen6 halamanPlugin LawofMarketsiamjheraldineBelum ada peringkat

- Supply: Summary and Introduction To SupplyDokumen8 halamanSupply: Summary and Introduction To SupplyUmer EhsanBelum ada peringkat

- Demand Curve: The Chart Below Shows That The Curve Is A Downward SlopeDokumen7 halamanDemand Curve: The Chart Below Shows That The Curve Is A Downward SlopePrince Waqas AliBelum ada peringkat

- Lecture Note #4Dokumen5 halamanLecture Note #4Lea AndreleiBelum ada peringkat

- Supply and Demand: For Other Uses, SeeDokumen18 halamanSupply and Demand: For Other Uses, SeeCDanielle ArejolaBelum ada peringkat

- ECON 301 CAT SolutionsDokumen5 halamanECON 301 CAT SolutionsVictor Paul 'dekarBelum ada peringkat

- Activity 81000Dokumen9 halamanActivity 81000Mary Grace NayveBelum ada peringkat

- Economics Basics: Supply and DemandDokumen8 halamanEconomics Basics: Supply and Demandrizqi febriyantiBelum ada peringkat

- "Buy Me This, Buy Me That": Ano Kaya Kung Cellphone Nnalang Bilhin Ko?Dokumen27 halaman"Buy Me This, Buy Me That": Ano Kaya Kung Cellphone Nnalang Bilhin Ko?Lovelyn RamirezBelum ada peringkat

- Chapter Two: Theory of Demand and SupplyDokumen30 halamanChapter Two: Theory of Demand and SupplyeyasuBelum ada peringkat

- Module 3 AssignmentDokumen4 halamanModule 3 AssignmentRitu Raj GogoiBelum ada peringkat

- How Demand Market Price Jan12 2015Dokumen5 halamanHow Demand Market Price Jan12 2015nivetithaBelum ada peringkat

- Introduction To Demand and SupplyDokumen5 halamanIntroduction To Demand and SupplyMA. FELIZIAH COLEEN BANUELOSBelum ada peringkat

- Suply Demand CurvesDokumen7 halamanSuply Demand CurvesonkaliyaBelum ada peringkat

- Chapter Two Introduction To EconomicsDokumen36 halamanChapter Two Introduction To Economicsnigusu deguBelum ada peringkat

- Supplementary Lesson Material For Module 2 Lesson 1 Part IDokumen4 halamanSupplementary Lesson Material For Module 2 Lesson 1 Part ILee Arne BarayugaBelum ada peringkat

- Demand and Supply: Dr. Sanja Samirana PattnayakDokumen51 halamanDemand and Supply: Dr. Sanja Samirana PattnayakSubhash MohanBelum ada peringkat

- How Demand and Supply Determine Market Price: PDF (55K) Agri-News This WeekDokumen6 halamanHow Demand and Supply Determine Market Price: PDF (55K) Agri-News This WeekMonika KshBelum ada peringkat

- As1 &2Dokumen29 halamanAs1 &2Emiru ayalewBelum ada peringkat

- Learning Objectives: Lecture Notes - CH 3 Demand, Supply and PriceDokumen6 halamanLearning Objectives: Lecture Notes - CH 3 Demand, Supply and PriceCassius SlimBelum ada peringkat

- Chapter 3Dokumen13 halamanChapter 3Bader F QasemBelum ada peringkat

- A. The Law of Demand: Market EconomyDokumen6 halamanA. The Law of Demand: Market EconomyLeo JoyBelum ada peringkat

- A. The Law of Demand: Market EconomyDokumen6 halamanA. The Law of Demand: Market EconomySagar KhandelwalBelum ada peringkat

- Chapter 11Dokumen10 halamanChapter 11CARMEN PEREZ GOMEZBelum ada peringkat

- Demand and Supply ModelDokumen24 halamanDemand and Supply ModelШугыла Есимхан100% (1)

- Lesson-7 Supply and Demand - Supply AnalysisDokumen7 halamanLesson-7 Supply and Demand - Supply AnalysisNilima GraceBelum ada peringkat

- Equilibrium Reflects The Perfect Balance of Supply and DemandDokumen8 halamanEquilibrium Reflects The Perfect Balance of Supply and DemandGözde GürlerBelum ada peringkat

- Economics BasicsDokumen9 halamanEconomics BasicsGermaine CasiñoBelum ada peringkat

- Demand and Supply: The BasicsDokumen24 halamanDemand and Supply: The BasicsjkanyuaBelum ada peringkat

- Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Seed CorporationDokumen1 halamanKhyber Pakhtunkhwa Seed CorporationFarhat Abbas DurraniBelum ada peringkat

- Sustainable Agriculture Dev For Food SecurityDokumen131 halamanSustainable Agriculture Dev For Food SecurityFarhat Abbas DurraniBelum ada peringkat

- Manual For Synopsis and Thesis PreperationDokumen73 halamanManual For Synopsis and Thesis PreperationFarhat Abbas DurraniBelum ada peringkat

- Supreme Court of Bangladesh Decision in Mulla Qadir CaseDokumen790 halamanSupreme Court of Bangladesh Decision in Mulla Qadir CaseFarhat Abbas DurraniBelum ada peringkat

- Biofertilizer ManualDokumen138 halamanBiofertilizer Manualvaibhav_taBelum ada peringkat

- Ghazi Ilm Deen Shaheed Rh-ADokumen97 halamanGhazi Ilm Deen Shaheed Rh-AFarhat Abbas DurraniBelum ada peringkat

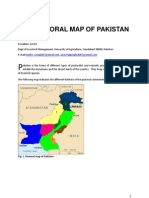

- The Pastoral Map of Pakistan: Abdul RaziqDokumen7 halamanThe Pastoral Map of Pakistan: Abdul RaziqFarhat Abbas DurraniBelum ada peringkat

- Indian Agriculture Market ReportDokumen2 halamanIndian Agriculture Market ReportFarhat Abbas DurraniBelum ada peringkat

- StatisticsDokumen2 halamanStatisticsFarhat Abbas DurraniBelum ada peringkat

- Economics AssignmentDokumen6 halamanEconomics Assignmenturoosa vayaniBelum ada peringkat

- Sample PDF of Tybcom Sem 6 Business Economics Smart Notes Book Bcom 3rd Year Mumbai University PDFDokumen19 halamanSample PDF of Tybcom Sem 6 Business Economics Smart Notes Book Bcom 3rd Year Mumbai University PDFRajkumar Moota50% (2)

- Economics Course Outline LAW ECON 1101Dokumen3 halamanEconomics Course Outline LAW ECON 1101Farooq e AzamBelum ada peringkat

- College Demand During Covid-19: William MohrDokumen5 halamanCollege Demand During Covid-19: William Mohrbm4Belum ada peringkat

- CS Syllabus 1 PDFDokumen71 halamanCS Syllabus 1 PDFMercy KaguaiBelum ada peringkat

- Supply and DemandDokumen13 halamanSupply and DemandBilal ChBelum ada peringkat

- QuizDokumen36 halamanQuizStormy88Belum ada peringkat

- Chapter 8-SupplyDokumen13 halamanChapter 8-SupplyBasheer KhaledBelum ada peringkat

- Entrepreneur Week 2Dokumen40 halamanEntrepreneur Week 2Mikel Nelson AmpoBelum ada peringkat

- The Instruments of Trade PolicyDokumen55 halamanThe Instruments of Trade PolicyMadalina RaceaBelum ada peringkat

- HW 3-Factors Affecting Demand and SupplyDokumen3 halamanHW 3-Factors Affecting Demand and Supply伊貝P-Belum ada peringkat

- Macroeconomics Principles and Policy 13th Edition Baumol Test Bank 1Dokumen70 halamanMacroeconomics Principles and Policy 13th Edition Baumol Test Bank 1gloria100% (60)

- Ch02 (1) Answers EconomicsDokumen19 halamanCh02 (1) Answers Economicssheetal tanejaBelum ada peringkat

- Notes of Marketing AnalyticsDokumen46 halamanNotes of Marketing AnalyticsAnuj SinghBelum ada peringkat

- Chapter 01Dokumen15 halamanChapter 01Alan Wong100% (1)

- Edexcel GCE: EconomicsDokumen24 halamanEdexcel GCE: EconomicsJimmy HklBelum ada peringkat

- Engineering Economics and Project FinancingDokumen149 halamanEngineering Economics and Project FinancingUmar FarouqBelum ada peringkat

- EconomicsDokumen19 halamanEconomicsnekkmatt100% (1)

- Case Analysis of UberDokumen4 halamanCase Analysis of UberWeke-sir CollinsBelum ada peringkat

- B A Economics PDFDokumen293 halamanB A Economics PDFthafsiraBelum ada peringkat

- Consumer and Producer SurplusDokumen32 halamanConsumer and Producer SurplusOsama NurBelum ada peringkat

- Political Economy NotesDokumen23 halamanPolitical Economy NotesDhivyaa ThayalanBelum ada peringkat