Top Down Approach and Analysis

Diunggah oleh

mustafa-ahmedJudul Asli

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Top Down Approach and Analysis

Diunggah oleh

mustafa-ahmedHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Stocks & Commodities V14:3 (124-129): Toop Down Investing with S&P's Sam Stovall by Thom Hartle

INTERVIEW

Top Down Investing with S&P's Sam Stovall

Some wander onto Wall Street by mistake, while others seem destined to find their way there. Sam Stovall is a member of Standard & Poor's Investment Policy Committee, editor of S&P's Industry Reports and author o f Standard & Poor's Guide to Sector Investing. Stovall spoke with STOCKS & COMMODITIES Editor Thom Hartle on December 20, 1995, via telephone interview about market cycles, sector investing and relative strength, among other topics.

I had all this data on industry indices, and anybody can find out when economic constractions and expansions started and ended, so I decided to determine what sectors performed the best during different periods of an economic cycle. That's how I became involved in sector investment and analysis. -Sam Stovall

Copyright (c) Technical Analysis Inc.

Stocks & Commodities V14:3 (124-129): Toop Down Investing with S&P's Sam Stovall by Thom Hartle

our father, Robert Stovall, is a well-known money manager on Wall Street. Did you start your career in finance too? No, I went to Muhlenberg College, which is a small college in Allentown, PA, and there I was certified to teach social studies on a secondary level. But there were no jobs available at the time, and if you could get one they didn't pay you very much. So my first job was with the time-sharing division of Control Data. What did you do? In a sense, I acted as an educator, but I taught people how to use the computer systems instead of social studies. The technology then was similar to the personal computers, but instead of using your own machine, you were using a machine connected to a computer in Cleveland, OH, by dialing a local telephone number and placing the phone into little rubber cups to connect with their modem. When was this? This was in 1978. I left Control Data after three years, and then for nine months I worked on the floor of the New York Mercantile Exchange (NYME) in the heating oil pit. That's quite a jump! How'd you get there?

Yes, it was a jump. The thing is, my father had been on Wall Street for 30 years, so I knew all about Wall Street and I wanted to see if I could try something there, but I wanted to put my own spin on it. Why I chose commodities I have no idea. I didn't stay long because I quickly realized trading in the pits was not for me, so I went back to Control Data as a systems analyst. Doing the same thing as you did the first time? No, my first stint there had been more as a marketing person, but for the second job I worked in systems development. Later on, I moved to Dun & Bradstreet and got my master's in business administration (MBA) in finance. After that, I switched over to Argus Research, and eventually became the editor-in-chief there. Then in 1989 I came to S&P. That's quite a varied background. Well, because of my background in desktop publishing as well as finance and marketing systems, I came in to develop new products. What was your first product? The first product I developed was called Industry Reports . S&P has had stock reports for decades; actually, our founder, Henry Poor, started writing buy, hold and sell recommendations on railroad companies back in the 1850s, so stock reports have been around for quite a while. But until Industry Reports , we never boiled it down to an industry level. How's it work? By having the analyst who follows, say, entertainment stocks and then having him or her write about their outlook for the entire industry moving forward. That was your first product? Yes. Since there was really no one there to edit and publish this new product, management said, "Well, why don't you just go ahead and do it?" And that was how I became the editor of Industry Reports , which today is an investment outlook on 80 industries with buy, hold and sell recommendations on 1,000 stocks. I jokingly say that the analysts do the work and I take the credit.

Copyright (c) Technical Analysis Inc.

Stocks & Commodities V14:3 (124-129): Toop Down Investing with S&P's Sam Stovall by Thom Hartle

That's not all that uncommon. It's not much of a joke either. You've published a book? That's right. Basically, my book is a top-down approach to investing: First, by looking at where the economy is headed in the economic cycle; and second, which industries should do well or poorly, based on that economic forecast. What's the value in doing that? The value is aptly illustrated by a study done by CDA/Weisenberger, which compared three different investment techniques over a 10-year period. They compared buy-and-hold, market timing and sector investing. How was the study set up? Buy and hold is self-explanatory, while market timing was defined as correctly predicting price changes in the overall stock market 10% or more in either direction, buying when prices are about to rise and selling when prices are about to decline. What about the sector? The sector strategist invested the entire portfolio in one of six sectors at the beginning of each year. Which sectors? The sectors were energy, financial services, gold, health care, technology and utilities. So what were the outcomes? Each investment method started with $1,000. At the end of the 10-year period, the buy and hold made a little more than $6,000. The market timing method made almost $15,000, and the sector selector made nearly $63,000. You can significantly outperform the market by about four times by correctly investing in the right sector. And And that got me thinking. I had all this data on industry indices, and anybody can find out when economic contractions and expansions started and ended, so I decided to determine what sectors performed the best during different periods of an economic cycle. And what did you decide to use as a cycle? I started with a couple of assumptions. First, there are five phases of an economic cycle (Figure 1). The first three occur in an economic expansion, and then I identified two phases of an economic contraction, or recession.

Copyright (c) Technical Analysis Inc.

Stocks & Commodities V14:3 (124-129): Toop Down Investing with S&P's Sam Stovall by Thom Hartle

Copyright (c) Technical Analysis Inc.

Stocks & Commodities V14:3 (124-129): Toop Down Investing with S&P's Sam Stovall by Thom Hartle

FIGURE 1: FIVE PHASES OF AN ECONOMIC CYCLE. The first three phases of an economic cycle occur in an economic expansion, and then two phases of an economic contraction, or recession. The first phase of the contraction is the defensive phase, when investors start to shift their money using a flight to safety mindset. Typically, at this point, the Federal Reserve is usually raising interest rates to cool economic growth.

What are the two phases? The first phase of the contraction is the defensive phase, which is basically when the stock market starts to tank and you have investors getting nervous and shifting their money using a flight-to- safety mindset. Typically, at this point, the Federal Reserve is usually raising interest rates to cool economic growth. I always heard that investors go to beverage stocks, food, tobacco and health-care stocks during these periods. The idea was that consumers still need to purchase products from these companies even during a recession. This was the sort of thing that I wanted to test. What happens next in the phase of an economic cycle? Then the Fed decides it's done too much to slow the economy; it realizes it has to change gears and start lowering interest rates. That's the second stage of the economic contraction, the interest-sensitive phase. How far did you look back? In the 1995 edition of my Guide to Sector Investing , I looked at the past 25 years, during which there were four complete economic expansions and five economic contractions. So, for instance, the economic expansion of November 1970 through November 1973 lasted 36 months. I simply took the 36 months and divided by three. So each phase lasted 12 months in my analysis. Then I calculated how each of the 88 industries in the S&P 500 performed during these 12 months and then how the S&P 500 performed during the same 12 months. And you tabulated these results? Yes, and then I looked to see which ones outperformed and which ones underperformed. Initially, I started doing the analysis as an average percentage basis, and then our economist suggested I look at it on a count basis [Editor's note: the number of times the industry outperformed the S&P during each phase], because in the four previous economic expansions, maybe this industry underperformed in three of them but then significantly outperformed in the fourth one. It could be enough to make it seem as if on average it always outperforms. I thought that was a good idea, so I used a count method. So you determined what was anecdotal and what was factual regarding investors' preferences

Copyright (c) Technical Analysis Inc.

Stocks & Commodities V14:3 (124-129): Toop Down Investing with S&P's Sam Stovall by Thom Hartle

during different phases of the economic cycle? That's right. I found 10 different sectors and, in general, when these sectors show their best performance (Figure 2). In a sense, that's the rotational pattern. I also came up with what I refer to as a batting average for each of the different industries.

FIGURE 2: THE ECONOMIC TRIANGLE. In general, the rotational pattern occurs among 10 different sectors, when these sectors show their best performance.

What did you do? Did you just measure straight performance? No. For instance, in order for an industry to rate a 1, it would have to outperform the market more than two times out of four during one of the economic cycles of the four economic expansions in the past 25 years. So it has to be more than 50%, not 50% or less. For example? For example, tobacco stocks outperformed the market only once in the early phase of the four expansions, four times in the middle phase and three times in the late phase. During the five economic contractions, tobacco stocks outperformed the market five times in both the early and late phase. Tobacco's batting average is a 4. That's pretty good! Sure. It tends to indicate that maybe you don't have to be such a great market timer when it comes to tobacco, and the same goes for the other industries with high batting averages. What are some other high scorers? I found that some industries, such as household products, tobacco, broadcast media and newspaper publishers, had very high batting averages. Then there were some others like autos, airlines, computer systems and heavy-duty trucks that had batting averages anywhere from 1 to zero (Figure 3). That meant there was no time when this industry consistently outperformed the market.

Copyright (c) Technical Analysis Inc.

Stocks & Commodities V14:3 (124-129): Toop Down Investing with S&P's Sam Stovall by Thom Hartle

FIGURE 3: SECTOR SCORECARD. Here are the batting averages for some of the best- and poorest-performing industries.

What are your thoughts about what drives the consistent winners? In some ways, especially household products, boring can be beautiful. In the past 10 years, household-product stocks have outperformed the market eight times. In the past 15 years, I think they've outperformed the market 11 times. So Peter Lynch, in his One Up On Wall Street , said, "Many times you should be focusing on those companies that look dull." He used the example of Automatic Data Processing [AUD] as a perennial winner. Well, carrying that thought one step further, everybody needs and uses household products - basically, soaps, cleansers, what have you, but they're also pretty much the last thing anyone really thinks about, just because they're necessities. They're not exciting, but they're consistent performers. So an investor could just concentrate on those industries? Exactly. If I'm an investor who's unable to monitor these stocks or these industries very closely but I do want to participate in sector investing, then I should be gravitating toward those industries with batting averages of 3 or 4. By the way, no industry has had a batting average of 5 of 5. Every industry must have a time when it's consolidating while the market is doing better. That's true. What indicators do you look at to get a handle on when an industry is starting to move? On the broad view, starting with the very top, I look at interest rates because interest rates pretty much drive almost everything, whether it's bonds or stocks. Investors tend to anticipate the economy going from expansion to

Copyright (c) Technical Analysis Inc.

Stocks & Commodities V14:3 (124-129): Toop Down Investing with S&P's Sam Stovall by Thom Hartle

contraction, and that's reflected in stock prices. Stock prices lead an economic recession by about six months, and they tend to anticipate an economic expansion by only about four to four and a half months. Why do you think there is a difference? I think fear has an awful lot to do with that. Investors and traders are more afraid of losing gains than they are of missing opportunities. The way an investor should analyze the market for sector investing is to look at interest rates and develop an opinion as to where we're headed in the economic cycle. You could look at GDP growth, industrial production, capacity utilization and a lot of those industrial and consumer indicators to determine if the economy is in a contracting or expanding phase. And thenAnd then, based on that, what might be the Federal Reserve's next move, you ask? Is it to stay the course because the expansion is moving at a very modest but controllable rate? Are they going to ease interest rates because the expansion is less than what they want and inflation is not a concern? Or are they going to raise rates because the expansion is stronger than anticipated and there seems to be inflation creeping into the marketplace? What next? To determine if the market has anticipated an expansion in the economy or a contraction. If there's a contraction, then the first thing you should see is investors switching from growth- and momentum-oriented stocks toward defensive stocks. Those stocks tend to continue rising in a falling stock market environment or lose less than the overall market loses during this contractionary stage. What about an economic expansion? If we're headed toward an economic contraction, or if we've been in a period of sluggishness and the Fed then starts to ease, then it might appear we're in the latter stages of an economic contraction, the second phase of an economic contraction. Interest rate-sensitive areas benefit, such as utilities and financials. Another tool to use to help you decide which phase the market is in is to look at which industries have done well in the past 12 months. This would give you sort of an indication of where we're headed. So you use the sector performance as a confirmation? In some ways, yes. In addition, don't forget that history can help guide you. If the average economic expansion lasts 50 months, then you can say each different phase takes about 17 months to occur. That's by no means a fail-safe, though; the expansions in the 1960s lasted 106 months, and the economic expansion of the 1980s lasted 92 months, and then you have some expansions that lasted only 13 months. When was that? That was in the early 1980s. Obviously, nothing is exact, but it does at least give you something of a benchmark. Is it possible you could have a fairly short-lived contraction phase and then return to an expansion phase? I think we saw that last year, because of the Fed-engineered economic slowdown, the "soft landing" they called it, that took place in the second quarter of 1995. Once we saw the Fed started easing interest rates in July, that was almost like a mini-economic cycle taking place within a broader economic cycle. The broad economic expansion started in March 1991. Because we haven't had a definitive statement by the National Bureau of Economic Research's Business Cycle Dating Committee to tell us we were in a recession, in my opinion we're still in an economic expansion. If you use Arthur Okun's method of deciding whether we've had a recession, you take a look at two quarters of gross domestic product (GDP) decline - which we haven't had either. But we had this little slowdown that took place in the second quarter. Not to mention the Fed cut rates. That's right, we had the first of two 25-basis-point cuts in interest rates. The first one took place in July and we've

Copyright (c) Technical Analysis Inc.

Stocks & Commodities V14:3 (124-129): Toop Down Investing with S&P's Sam Stovall by Thom Hartle

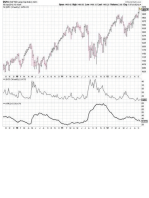

been seeing a lot of the financial stocks and a lot of the transportation stocks do very well since then. Along with technology stocks. Right. They tend to prosper earlier in the economic cycle than later. Those industries or sectors along with the cuts in the interest rates by the Fed confirmed the likelihood of the economy moving back into the early expansion stage? That's right. Now obviously, there are always going to be times in which just looking at the individual industries, let's say over a month, two months, six months, you might be unable to determine where we are in the cycle. You need some sort of guidance to see how rotation is taking place. That's why in the 1996 edition of Guide to Sector Investing , I added relative strength analysis, because using the triangle alone to help me decide which industry should do well or poorly wasn't enough. How do you use relative strength as a timing tool? For example, the auto stocks in March 1995 fell more than 20% in the past 12 months, and looking at a 12-month relative strength, that's the industry's performance over the previous 12 months versus the S&P 500. So the auto stocks got to a level that's actually the lowest or close to the lowest that it has been in the last 25 years. And And this might be the time for a long-term buy. By looking at the 12-month relative strength performance of an industry, I can plot a visual pattern and see when the industry tends to peak relative to the S&P and when it tends to trough and so forth. Then I decided that I needed a way to plot a buy/sell channel. How did you design that? I used one standard deviation from the mean, since that indicates two-thirds of all observations fall within that band. If a third falls outside that band, that may indicate the industry is either overbought or oversold or at least identify a situation that is overbought or oversold and you might want to look at it in greater detail. At the time I designed the channel, auto stocks were significantly below the mean minus one standard deviation, which is where it starts to look attractive. What else besides relative strength do you look at? I made what I refer to as my sector scorecard. I wanted to know how well these industries have done year to date, how they've done in the past month or three months. Then, to give a little relevance, I want to know how they performed last year. That's the no-brainer stuff that starts off the sector scorecard. I also have the price/earnings ratio (P/E), relative P/E, indicate dividend yield currently and then their 25-year average to decide whether it's high or low based on the average. Then I have that relative strength, so I've got the current 12-month relative strength for this industry. Then I have the high-side standard deviation, saying it's expensive if it's above this number. Then I have the low-side standard deviation, which means it's cheap if it's below this number, and then I show what the movement has been in the last three months. Do you use the standard method to calculate relative strength? No, my relative strength is a little different from the usual method of measuring relative strength. As I understand it, a normal relative strength goes from zero to 100, but the way I measure relative strength says that if over the past 12 months a certain industry has equaled the performance of the S&P 500, its relative strength is 100. If it has underperformed the S&P 500, its relative strength is less than 100, and if it has outperformed the market, its relative strength is greater than 100. Give me an example of how you'd use that. Sure. For instance, at the end of November 1995, aluminum stocks were at a relative strength of 102 (Figure 4). They start to look expensive above 119, but we're certainly not there; and they start to look cheap below 81, and they're certainly not there, either. Then the question becomes how they've performed in the past three months. Well,

Copyright (c) Technical Analysis Inc.

Stocks & Commodities V14:3 (124-129): Toop Down Investing with S&P's Sam Stovall by Thom Hartle

they'd fallen five relative strength points and I know that maybe four or five months previously aluminum stocks were above 119 on a 12-month relative strength. While I focus on the 12-month relative strength indicator as a good long-term indicator of bargains or overpriced situations, sometimes it also works on the short term as well. In essence, as an analogy, if somebody likes to hunt for straw hats in the summer or overcoats in the winter, this will tell you which are on sale.

FIGURE 4: 25-YEAR TREND IN 12-MONTH RELATIVE STRENGTH FOR THE S&P ALUMINUM INDEX. At the end of November 1995, aluminum stocks were at a relative strength of 102. While Stovall focuses on the 12-month relative strength indicator as a good long-term indicator of bargains or overpriced situations, sometimes it also works on the short term as well.

What else do you keep on your scorecard? I track relative P/Es, too. I look at the average P/Es over the past 25 years on an industry-by-industry basis. It can really be different, depending on the industry. For example, the average P/E for auto stocks is 8.7, where it's 22.1 for semiconductor stocks. I wondered if there was a similar type of high-low band for the industries and found out that yes, that is the case. [Editor's note: The sector scorecard is available by calling Standard & Poor's Reports On Demand at 800 292-0808.] Relative strength measurement can alert you to opportunities, but should we dig deeper? Relative strength does alert you to situations. I would look at the general industry writeups, what our analyst or someone else happens to think is the investment outlook for this particular industry. All the historical work looks at just that. For instance, how has this industry performed during specific conditions in the past? Take a look at aerospace, which is an industry that has outperformed four out of four times in the first third of an economic expansion and then tended to underperform in all succeeding phases of the expansion and contraction. But all the observations occurred when the Cold War was still going on. Now that the Berlin Wall is down, how does that change things? That's why you have to take a look at what the analysts happen to think about the fundamental conditions in that industry. What else?

Copyright (c) Technical Analysis Inc.

Stocks & Commodities V14:3 (124-129): Toop Down Investing with S&P's Sam Stovall by Thom Hartle

Then I think you should look at the recommendations, either what we have or some other companies might have to decide which companies are then best positioned in those industries. Or you could just stop at the industry level and buy industry-specific mutual funds based on relative strength and fundamental outlooks. The newest edition of previous editions? Guide to Sector Investing is out this spring. What are the changes from

I'm going back 50 years rather than 25 years in terms of the economic analysis and I'm adding the relative strength work and updating what our analysts think lies ahead for industries in the 1990s. Thanks for your time, Sam.

Relative strength does alert you to situations. Look at the general industry writeups, what our analyst or someone else happens to think is the investment outlook for this particular industry. How has this industry performed during specific conditions? RELATED READING Lynch, Peter [1989]. One Up On Wall Street, Simon & Schuster. National Bureau of Economic Research, 1050 Massachusetts Ave., 3d floor, Cambridge, MA 02138. Stovall, Sam [1996]. Standard & Poor's Guide to Sector Investing , McGraw-Hill, Inc.

end

Copyright (c) Technical Analysis Inc.

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- Two Centuries of Momentum: UmmaryDokumen27 halamanTwo Centuries of Momentum: Ummaryjorge bergoglio100% (1)

- Sector Trading StrategiesDokumen16 halamanSector Trading Strategiesfernando_zapata_41100% (1)

- OMS Chartbook Morgan-Stanley PDFDokumen253 halamanOMS Chartbook Morgan-Stanley PDFantics20Belum ada peringkat

- Sector Business Cycle AnalysisDokumen9 halamanSector Business Cycle AnalysisGabriela Medrano100% (1)

- 007.the Value of Not Being SureDokumen2 halaman007.the Value of Not Being SureJames WarrenBelum ada peringkat

- Seling Fast and Buying Slow - Heuristics and Trading Performance of Institutional InvestorsDokumen84 halamanSeling Fast and Buying Slow - Heuristics and Trading Performance of Institutional InvestorsFabio Tessari100% (2)

- Words From the Wise - Ed Thorp InterviewDokumen22 halamanWords From the Wise - Ed Thorp Interviewfab62100% (1)

- FINANCIAL FRAUD DETECTION THROUGHOUT HISTORYDokumen40 halamanFINANCIAL FRAUD DETECTION THROUGHOUT HISTORYkabhijit04Belum ada peringkat

- The Global Macro Edge - Maximizi - John Netto PDFDokumen1.023 halamanThe Global Macro Edge - Maximizi - John Netto PDFchauchau100% (8)

- The Investment Clock - Trevor GreethamDokumen28 halamanThe Investment Clock - Trevor Greethamcherrera73Belum ada peringkat

- Stubs Maurece Schiller 1966 PDFDokumen15 halamanStubs Maurece Schiller 1966 PDFSriram Ramesh100% (1)

- Sector Rotation StrategyDokumen53 halamanSector Rotation StrategySylvia KunthieBelum ada peringkat

- Tarheel Consultancy Services: BangaloreDokumen170 halamanTarheel Consultancy Services: BangaloreSumit SinghBelum ada peringkat

- Momentum Factor Basics and Robeco SolutionDokumen7 halamanMomentum Factor Basics and Robeco Solutionbodo0% (1)

- Relative Strength Strategies For InvestingDokumen22 halamanRelative Strength Strategies For Investingthe_akinitiBelum ada peringkat

- Enterprise Risk Management - Beyond TheoryDokumen34 halamanEnterprise Risk Management - Beyond Theoryjcl_da_costa6894100% (4)

- An Introduction To Volatility, VIX, and VXX: What Is Volatility? Volatility. Realized Volatility Refers To HowDokumen8 halamanAn Introduction To Volatility, VIX, and VXX: What Is Volatility? Volatility. Realized Volatility Refers To Howchris mbaBelum ada peringkat

- John J. Murphy - Simple Sector TradingDokumen34 halamanJohn J. Murphy - Simple Sector TradingMike Ng67% (3)

- Does Sector Rotation WorkDokumen9 halamanDoes Sector Rotation WorkfendyBelum ada peringkat

- Goldman Sachs Equity Research ReportDokumen2 halamanGoldman Sachs Equity Research ReportSaras Dalmia0% (1)

- John Murphy's Intermarket Analysis Using ETFsDokumen20 halamanJohn Murphy's Intermarket Analysis Using ETFsm074h3u5100% (4)

- Macroeconomic Dashboards For Tactical Asset AllocationDokumen12 halamanMacroeconomic Dashboards For Tactical Asset Allocationyin xuBelum ada peringkat

- Teaching Market Making with a Game SimulationDokumen4 halamanTeaching Market Making with a Game SimulationRamkrishna LanjewarBelum ada peringkat

- Peacock Bull BearDokumen22 halamanPeacock Bull BearClaraBelum ada peringkat

- Sector Rotation Over Business CyclesDokumen34 halamanSector Rotation Over Business CyclesHenry Do100% (1)

- Michael Burry - Bloomberg TranscriptDokumen26 halamanMichael Burry - Bloomberg TranscriptFinanceTrendsBelum ada peringkat

- Short SqueezeDokumen6 halamanShort Squeezealphatrends100% (1)

- Understanding RecessionsDokumen3 halamanUnderstanding RecessionsVariant Perception Research100% (1)

- Invest Using Wall Street Legends' StrategiesDokumen32 halamanInvest Using Wall Street Legends' StrategiesMohammad JoharBelum ada peringkat

- European Debt CrisisDokumen21 halamanEuropean Debt CrisisPrabhat PareekBelum ada peringkat

- Learn from Top FX Traders' StrategiesDokumen11 halamanLearn from Top FX Traders' StrategiesWayne Gonsalves100% (2)

- What's A 'Gamma Flip' (And Why Should You Care) - Zero HedgeDokumen5 halamanWhat's A 'Gamma Flip' (And Why Should You Care) - Zero HedgeMaulik Shah100% (1)

- CASE 2: Eskimo Pie Corporation ValuationDokumen7 halamanCASE 2: Eskimo Pie Corporation ValuationIrakli Salia100% (1)

- Tying Free Cash Flows To Market Valuation - Robert Howell - Financial ExecutiveDokumen4 halamanTying Free Cash Flows To Market Valuation - Robert Howell - Financial Executivetatsrus1Belum ada peringkat

- Sectors and Styles: A New Approach to Outperforming the MarketDari EverandSectors and Styles: A New Approach to Outperforming the MarketPenilaian: 1 dari 5 bintang1/5 (1)

- Deep Thought on Quant StrategiesDokumen1 halamanDeep Thought on Quant Strategiespatar greatBelum ada peringkat

- Quantitative Momentum Philosophy FinalDokumen8 halamanQuantitative Momentum Philosophy Finalalexa_sherpyBelum ada peringkat

- CitiGroup On TrendFollowingDokumen49 halamanCitiGroup On TrendFollowingGabBelum ada peringkat

- Wayne Whaley - Planes, Trains and AutomobilesDokumen16 halamanWayne Whaley - Planes, Trains and AutomobilesMacroCharts100% (2)

- Capital Returns: Investing Through the Capital Cycle: A Money Manager’s Reports 2002-15Dari EverandCapital Returns: Investing Through the Capital Cycle: A Money Manager’s Reports 2002-15Edward ChancellorPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (3)

- How To Identify Wide MoatsDokumen18 halamanHow To Identify Wide MoatsInnerScorecardBelum ada peringkat

- Adaptive Markets - Andrew LoDokumen22 halamanAdaptive Markets - Andrew LoQuickie Sanders100% (4)

- Studying Different Systematic Value Investing Strategies On The Eurozone MarketDokumen38 halamanStudying Different Systematic Value Investing Strategies On The Eurozone Marketcaque40Belum ada peringkat

- Foundations of Factor InvestingDokumen33 halamanFoundations of Factor Investingnamhvu99Belum ada peringkat

- 52-Week High and Momentum InvestingDokumen32 halaman52-Week High and Momentum InvestingCandide17Belum ada peringkat

- Market MicrostructureDokumen15 halamanMarket MicrostructureBen Gdna100% (2)

- Publication NovDokumen86 halamanPublication Novmustafa-ahmedBelum ada peringkat

- Bruce Greenwald Briefing BookDokumen24 halamanBruce Greenwald Briefing BookguruekBelum ada peringkat

- Finding Alpha - Eric FalkensteinDokumen310 halamanFinding Alpha - Eric Falkensteinahmad_korosBelum ada peringkat

- The Game in Wall Street and How To Play It Successfully by Hoyle PDFDokumen99 halamanThe Game in Wall Street and How To Play It Successfully by Hoyle PDFBhaskar Agarwal100% (1)

- 002 - Bloomberg Guide To VolatilityDokumen5 halaman002 - Bloomberg Guide To VolatilityDario OarioBelum ada peringkat

- Linneman Letter Spring 2019Dokumen4 halamanLinneman Letter Spring 2019paul changBelum ada peringkat

- Druckenmiller and Canada: Generational TheftDokumen20 halamanDruckenmiller and Canada: Generational Theftbowdoinorient100% (1)

- Edition 1Dokumen2 halamanEdition 1Angelia ThomasBelum ada peringkat

- Traders JuneDokumen71 halamanTraders Junemustafa-ahmedBelum ada peringkat

- Strategic and Tactical Asset Allocation: An Integrated ApproachDari EverandStrategic and Tactical Asset Allocation: An Integrated ApproachBelum ada peringkat

- Market MakingDokumen7 halamanMarket MakingLukash KotatkoBelum ada peringkat

- TAIL RISK HEDGING: Creating Robust Portfolios for Volatile MarketsDari EverandTAIL RISK HEDGING: Creating Robust Portfolios for Volatile MarketsBelum ada peringkat

- Pairs TradingDokumen47 halamanPairs TradingMilind KhargeBelum ada peringkat

- AQR Fundamental Trends and Dislocated Markets An Integrated Approach To Global MacroDokumen28 halamanAQR Fundamental Trends and Dislocated Markets An Integrated Approach To Global MacroMatthew Liew100% (1)

- Why Financial Markets Rise Slowly but Fall Sharply: Analysing market behaviour with behavioural financeDari EverandWhy Financial Markets Rise Slowly but Fall Sharply: Analysing market behaviour with behavioural financeBelum ada peringkat

- JPM Correlations RMC 20151 KolanovicDokumen22 halamanJPM Correlations RMC 20151 Kolanovicdoc_oz3298100% (1)

- Burry WriteupsDokumen15 halamanBurry WriteupseclecticvalueBelum ada peringkat

- Why Does The Yield Curve Predict Economic ActivityDokumen43 halamanWhy Does The Yield Curve Predict Economic Activitymustafa-ahmedBelum ada peringkat

- Contact and Strategy Details for MUTIS Commodities FundDokumen2 halamanContact and Strategy Details for MUTIS Commodities Fundmustafa-ahmedBelum ada peringkat

- Pressing Pause: BG GroupDokumen17 halamanPressing Pause: BG Groupmustafa-ahmedBelum ada peringkat

- ACM Shipping Group TransportationDokumen12 halamanACM Shipping Group Transportationmustafa-ahmedBelum ada peringkat

- MorningstarEquityResearch MethodologyDokumen8 halamanMorningstarEquityResearch Methodologymustafa-ahmedBelum ada peringkat

- 22 08 13 Maths QuestionsDokumen4 halaman22 08 13 Maths Questionsmustafa-ahmedBelum ada peringkat

- Sample Investment PolicyDokumen3 halamanSample Investment Policymustafa-ahmedBelum ada peringkat

- Unemployment and Business Cycles: WWW - Federalreserve.gov/pubs/ifdpDokumen63 halamanUnemployment and Business Cycles: WWW - Federalreserve.gov/pubs/ifdpTBP_Think_TankBelum ada peringkat

- Treasury Spread and Recession PredictionDokumen1 halamanTreasury Spread and Recession Predictionmustafa-ahmedBelum ada peringkat

- 22 08 13 Maths QuestionsDokumen4 halaman22 08 13 Maths Questionsmustafa-ahmedBelum ada peringkat

- 109EC IndustryDokumen12 halaman109EC IndustryMaster TanBelum ada peringkat

- MorningstarEquityResearch MethodologyDokumen8 halamanMorningstarEquityResearch Methodologymustafa-ahmedBelum ada peringkat

- DCF - InvestopediaDokumen16 halamanDCF - Investopediamustafa-ahmedBelum ada peringkat

- Bii Dividend Deluge Etp q2 2013 UsDokumen8 halamanBii Dividend Deluge Etp q2 2013 Usmustafa-ahmedBelum ada peringkat

- Morningstar's Investment Policy Worksheet: $ $ Years %Dokumen2 halamanMorningstar's Investment Policy Worksheet: $ $ Years %mustafa-ahmedBelum ada peringkat

- Present Value TablesDokumen4 halamanPresent Value TablesstcreamBelum ada peringkat

- Understanding EconomicDokumen4 halamanUnderstanding Economicmustafa-ahmedBelum ada peringkat

- The Global View: What Does The ISM Mean For US Equities?Dokumen5 halamanThe Global View: What Does The ISM Mean For US Equities?mustafa-ahmedBelum ada peringkat

- Understanding EconomicDokumen4 halamanUnderstanding Economicmustafa-ahmedBelum ada peringkat

- OptionsDokumen12 halamanOptionsmustafa-ahmedBelum ada peringkat

- EquityclassmethodologyDokumen33 halamanEquityclassmethodologymustafa-ahmedBelum ada peringkat

- Kelly CriterionDokumen14 halamanKelly Criterionmustafa-ahmedBelum ada peringkat

- Analysis and Uses of Financial StatementDokumen141 halamanAnalysis and Uses of Financial StatementEmmanuel Khonga100% (1)

- Howard DaviesDokumen30 halamanHoward Daviesmustafa-ahmedBelum ada peringkat

- The Toyota WayscDokumen20 halamanThe Toyota Wayscmustafa-ahmedBelum ada peringkat

- Writing With Flair WorkbookDokumen20 halamanWriting With Flair WorkbookLEOBelum ada peringkat

- Civil Services Mentor September 2011 WWW - UpscportalDokumen93 halamanCivil Services Mentor September 2011 WWW - UpscportalLokesh VermaBelum ada peringkat

- Client and Creditor PresentationDokumen17 halamanClient and Creditor PresentationLily SternBelum ada peringkat

- America Movil SAB de CVDokumen11 halamanAmerica Movil SAB de CVLuis Fernando EscobarBelum ada peringkat

- Credit Risk ManagementDokumen85 halamanCredit Risk ManagementDarpan GawadeBelum ada peringkat

- California Leads U.S. Economy, Away From Trump: The Domestic SuccessDokumen3 halamanCalifornia Leads U.S. Economy, Away From Trump: The Domestic Success洪侊增Belum ada peringkat

- FMS - Credit RatingDokumen10 halamanFMS - Credit RatingSteve Kurien JacobBelum ada peringkat

- INDONESIAN SECURITY OUTLOOK REMAINS STABLE AND POSITIVEDokumen6 halamanINDONESIAN SECURITY OUTLOOK REMAINS STABLE AND POSITIVEaddi.Belum ada peringkat

- Senate Hearing, 109TH Congress - Examining The Role of Credit Rating Agencies in The Captial MarketsDokumen206 halamanSenate Hearing, 109TH Congress - Examining The Role of Credit Rating Agencies in The Captial MarketsScribd Government DocsBelum ada peringkat

- Lending Risk MitigationDokumen33 halamanLending Risk MitigationdhwaniBelum ada peringkat

- ESDokumen335 halamanESVivechan GunpalBelum ada peringkat

- Press Release FinalDokumen4 halamanPress Release FinalNeil SmithBelum ada peringkat

- Capital IQ SPCIQ Fundamentals v2Dokumen4 halamanCapital IQ SPCIQ Fundamentals v2Sandra CruzBelum ada peringkat

- Standard & Poor's Business and Financial Terms July 2014Dokumen25 halamanStandard & Poor's Business and Financial Terms July 2014Andy LeungBelum ada peringkat

- Elkhorn Investments ETF Performance: Designed With Purpose. Research Driven ETF SolutionsDokumen2 halamanElkhorn Investments ETF Performance: Designed With Purpose. Research Driven ETF SolutionsvvitoyBelum ada peringkat

- Structured Capital Strategies Fact CardDokumen6 halamanStructured Capital Strategies Fact CardSoumen BoseBelum ada peringkat

- Financial Times USA 4 April 2017 PDFDokumen32 halamanFinancial Times USA 4 April 2017 PDFНаранЭрдэнэBelum ada peringkat

- PruLink Fund Objectives and 2012 Market ReviewDokumen65 halamanPruLink Fund Objectives and 2012 Market ReviewAnnBelum ada peringkat

- Global Reinsurance Highlights 2015Dokumen80 halamanGlobal Reinsurance Highlights 2015Jamal Al-GhamdiBelum ada peringkat

- 1334670994binder2Dokumen39 halaman1334670994binder2CoolerAdsBelum ada peringkat

- Finance Department Notifications-2003 (165-204)Dokumen40 halamanFinance Department Notifications-2003 (165-204)Humayoun Ahmad Farooqi100% (2)

- 04 SandP Exhibit4 v2Dokumen8 halaman04 SandP Exhibit4 v2Nabeel KhanBelum ada peringkat

- Seven: Interest Rates and Bond ValuationDokumen42 halamanSeven: Interest Rates and Bond ValuationPrasanna IyerBelum ada peringkat