A Mass Burial From The Cemetery of Kerameikos

Diunggah oleh

LudwigRoss100%(1)100% menganggap dokumen ini bermanfaat (1 suara)

1K tayangan15 halamanA unique mass grave and nearly 1,000 tombs from the fifth and fourth century B.C. were recovered during excavations prior to construction of a subway station just outside Athens' ancient Kerameikos cemetery. Both the mass grave and the tombs were destroyed after rescue excavations.

Located near the surface, the mass grave was excavated during 1994-95 by Efi Baziotopoulou-Valavani of the Third Ephoreia (Directorate) of Antiquities. Inside a shaft were some 90 skeletons, ten belonging to children. Baziotopoulou thinks a tumulus crowning the shaft may have contained 150 people. Skeletons in the graves were placed helter-skelter with no soil between them. It was bordered by a low wall that seems to have protected the cemetery from a marsh. Along with the skeletons, various ceramic burial offerings were found, far fewer than excavators expected.

Judul Asli

A mass burial from the cemetery of Kerameikos

Hak Cipta

© Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Format Tersedia

PDF, TXT atau baca online dari Scribd

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniA unique mass grave and nearly 1,000 tombs from the fifth and fourth century B.C. were recovered during excavations prior to construction of a subway station just outside Athens' ancient Kerameikos cemetery. Both the mass grave and the tombs were destroyed after rescue excavations.

Located near the surface, the mass grave was excavated during 1994-95 by Efi Baziotopoulou-Valavani of the Third Ephoreia (Directorate) of Antiquities. Inside a shaft were some 90 skeletons, ten belonging to children. Baziotopoulou thinks a tumulus crowning the shaft may have contained 150 people. Skeletons in the graves were placed helter-skelter with no soil between them. It was bordered by a low wall that seems to have protected the cemetery from a marsh. Along with the skeletons, various ceramic burial offerings were found, far fewer than excavators expected.

Hak Cipta:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Format Tersedia

Unduh sebagai PDF, TXT atau baca online dari Scribd

100%(1)100% menganggap dokumen ini bermanfaat (1 suara)

1K tayangan15 halamanA Mass Burial From The Cemetery of Kerameikos

Diunggah oleh

LudwigRossA unique mass grave and nearly 1,000 tombs from the fifth and fourth century B.C. were recovered during excavations prior to construction of a subway station just outside Athens' ancient Kerameikos cemetery. Both the mass grave and the tombs were destroyed after rescue excavations.

Located near the surface, the mass grave was excavated during 1994-95 by Efi Baziotopoulou-Valavani of the Third Ephoreia (Directorate) of Antiquities. Inside a shaft were some 90 skeletons, ten belonging to children. Baziotopoulou thinks a tumulus crowning the shaft may have contained 150 people. Skeletons in the graves were placed helter-skelter with no soil between them. It was bordered by a low wall that seems to have protected the cemetery from a marsh. Along with the skeletons, various ceramic burial offerings were found, far fewer than excavators expected.

Hak Cipta:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Format Tersedia

Unduh sebagai PDF, TXT atau baca online dari Scribd

Anda di halaman 1dari 15

12

A mass burial from the cemetery of Kerameikos

Effie Baziotopoulou-Valavani

The construction of two new lines of the Metropoli-

tan Railway of Athens created the opportunity for

five extensive excavations and for several ones of

smaller scale in the centre of Athens between 1993

and 1998, under the direction ofDrs Th. Karagiorga

and L. Parlama.

A large number of the finds were exhibited in the

Museum of Cycladic Art in Athens, until the end of

2001 and were accompanied by the publication of a

catalogue titled The City beneath the City, with re-

ports and commentary on the excavation as well.

1

I wish to express my wann thanks to the Honorary Ephor of

Antiquities Dr. Th. Karagiorga and to the Ephor of the 3rd

Ephorate of Athens Dr. L. Parlama for their help during the study

of the material. I am also grateful to M. Tiverios, U. Knigge and

H. Zervoudaki for the discussion on the chronology of the pottery.

I am also indebted to my colleagues G. Alexopoulos, G. Drakotou,

D. Kyriakou, A. Matthaiou, D. Tsouklidou and Al. Heliaki for

their kind help. Finally, I express my thanks to Professor Bert

Smith, for his invitation to the colloquium, M. Starnatopoulou and

M. Y eroulanou for their kind help and the corrections to my

English text. This study would not have been completed without

the continuous help and encouragement of my husband P.

Valavanis.

Abbreviations

Agora Xll = B.A. Sparkes and L. Talcott, The Athenian Agora

Xll: Black and Plain Pottery of the 6th, 5th and 4th centuries

B. C. (Princeton 1970).

CbC = L. Parlama and N. Stampolidis (eds), The City beneath the

City (Athens 2000).

felten, 'Lekythen' =F. Felten, 'Weissgrundige Lekythen aus dem

Athener Kerarneikos', AM91 (1976), 77-113.

Kerameikos VII.2 = E. Kunze-Gotte, K. Tancke and K. Viemeisel,

Kerameikos VII.2: Die Beigaben (Berlin 1999).

Kurtz, AWL= D.C. Kurtz, Athenian White Lekythoi. Patterns and

Painters (Oxford 1975).

Kurtz and Boardman = D.C. Kurtz and J. Boardrnan, Greek Burial

Customs (London 1971).

Papaspyridi = S. Papaspyridi, ''0 'TExvi 'tTJt; 'tOOV Kal..aJ.lrov' 'trov

AEUKOOV AT]KU9rov', ADelt 8 (1923) A, 117-146.

Rhodes, Thucydides = P.J. Rhodes (ed.), Thucydides' History li

(Warminster 1988).

187

To Dr. Theodora Karagiorga

Some other finds, as well as several copies, are ex-

hibited in the permanent exhibitions of the central

Railway stations. Most of the large scale excavations

took place at the site of the railway stations. Al-

though very few impressive finds were discovered,

problems pertaining to the topography of the ancient

city were re-examined and clarified.

2

One of the extended excavations was in the

Kerameikos station, at a very short distance from the

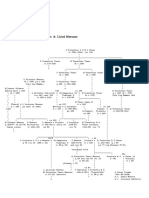

north-west part of the archaeological site [fig. 1].

3

This station remained at the centre of our concern for

a long time, since the tunnel could approach the sta-

tion only from beneath the archaeological site at a

shallow depth. The anxiety and opposition of the

archaeological community, because of the risks

posed to the monuments, persuaded the civil au-

thorities to alter their plans for the station and divert

the tunnel away from the site. By that time, the exca-

vation of the station had almost been completed, but

its last and particularly dense sector close to the

Rudolph = W. Rudolph, Die Bauchlekythos; ein Beitrag zur

Formgeschichte der attischen Keramik des 5. Jhs. v. Chr.

(Bloomington 1971).

Schilardi = D. Schilardi, The Thespian Polyandrion (424 B.C.).

The Excavation and the Finds from a Thespian State Burial

(Ann Arbor 1977).

Schliirb-Viemeisel = B. Sch!Orb-Viemeisel, 'Eridanos Nekropole',

AM81 (1966), 4-111.

Talcott, 'Stamped Ware' = L. Talcott, 'Attic Black Glazed

Stamped Ware and Other Pottery from a 5th c. Well', Hesperia

4 (1935), 477-523.

Reports on the excavation and generally on the work of the

'Metro' have been published in Horos 6 (1988), 87-108 (Th.

Karagiorga-Stathakopoulou) and Horos 10-12 (1992-1998), 521-

544 (L. Parlama).

1

CbC.

2

The reference is mainly for the excavation at Syntagrna Square,

Evangelismos and Kerameikos. See the excavation reports in CbC.

3

CbC, 264ff.

E. Baziotopou/ou-Va/avani

Figure l. Map of the Kerameikos area (the excavation area in dark grey).

188

~

r

\

A mass burial from the cemetery of Kerameikos

CD

0 I 2 3 'j.

Figure 2. Plan of the cemetery discovered during the recent excavations in Kerameikos.

189

E. Baziotopoulou- Valavani

Sacred Way remained, and is to be transformed into

an archaeological site.

Excavation data

Scattered in an area of about 0.15 ha, 1191 burials

dating from the early 7th century BC to the Roman

period were investigated under a disturbed earth fill,

which was caused by the intensive quarrying for sand

used for construction purposes in the capital of the

new Greek Kingdom in the 19th century [fig. 2].

4

The continuation of the known Classical cemetery

westwards was thus confirmed. The cemetery of

Kerameikos extended chiefly within the triangle

formed by the Sacred Way to the north, the Street of

Tombs to the south and a low enclosure - a sort of

retaining wall - to the west, situated about 200 m

from the city wall [fig. 2A]. No large luxurious

monuments were found, nor fragments of architec-

tural members or monumental grave reliefs. Their

absence is explained not only by the disturbance of

the earth fill above the graves but also by the fact that

this part of the cemetery lay at a distance from the

nucleus of the necropolis, which was close to the

walls and the gates.

However, the excavation provided us with important

data on the topography of the region; at the same

time, it yielded finds that relate to historical events,

such as the two mass burials found in the centre and

by the north-western edge of the cemetery. The first

was a rectangular shaft [fig. 2B], where 27 adults

were inhumed, one beside the other in two successive

layers. No grave offerings were found; still, the

chronology of the burial is derived from the sherds

found at the bottom of the shaft, which was the origi-

nal floor level of this common burial. Since the

sherds are dated to the decade of 420 BC, the burial

must be connected with the events of the Peloponne-

sian War.

The most interesting and impressive mass burial was

a simple pit of rather irregular shape, 6.50 m long

and 1.60 m deep [fig. 2C], discovered at a depth of

4.30 m from the surface. Its excavation proved par-

ticularly difficult, because of the superimposed dis-

turbed fills ap.d of five intrusions into the shaft,

which had occurred within a 1 00-year period fol-

lowing the burial. At its south edge, the pit was dis-

turbed by tile graves; only one of them yielded an

4

Information for the area of the Kerameikos before the excavation

by the German Archaeological Institute, in L. Ross,

1ca1 avaKozvrouE:u; an6 UfV EUaoa (1832-1833), Ei:voz Ilopl'f/Yrrctr;

urov EU'f/VIKO Xd>po 3 (Athens 1976); B. Petrakos, ''H c'xvaO"Jcacpl)

'to'il c'x1to 'tl)v 'ApxatoA.oyucl) 'E'tatpeiu', '0

Mev-rrop 48 (1998), 119-207.

190

offering: a squat aryballos of the late 5th-early 4th

century BC. A pyre in a shaft was discovered at its

west edge; it was totally disturbed, probably by the

foundation works for the Vegetable Market of Ath-

ens established in this region at the end of the 19th

century. Two intrusions (twins) at the centre of the

pit, dated in the third quarter of the 4th century ac-

cording to the sherds of coarse-ware pottery that

were contained in them, destroyed the greatest part of

the mass burial. Consequently, the information we

were able to extract came by and large from isolated

heaps of soil that had remained undisturbed.

The first bodies, facing towards the edge of the pit,

appeared in its east sector [fig. 3]. Beneath them

were other burials in more than five successive lay-

ers, without any intervening soil between them. The

excavation revealed successive burial levels of 89

male and female bodies, buried in a disorderly fash-

ion and usually in extended position, but also in po-

sitions directed by the shape and size of the pit. At

the lower levels, the deceased were more widely

spaced and it seems that they had been covered with

some earth; still, their position and direction re-

mained in the same disorder as in the upper layers.

The rough rock of the region constituted the bottom

and the lower sides of the pit. At the bottom and by

its south-western edge 30 skulls were found, from

exhumation of earlier burials that were disturbed by

the pit of the mass burial. At this lower level among

the first deceased, a man had been put in a hollow of

the pit in a half-erect position. In the upper layer, 8

enchytrismoi of infants were found among the de-

ceased. Contrary to the careless inhumation of the

adults, the children seem to have been treated with

special care. The infants' bodies were not buried in a

pot but they were covered by one large amphora

sherd, by two halves of different pots or by a half

pot. All these pots were found broken or smashed.

5

The grave offerings consisted of 30 small vases

scattered among the dead, especially in the lower

layers. It is noticeable that the body of a pelike was

found 0.50 m deeper than its lid. Considering the

actual number of the dead the offerings were very

few; initially there would have been at least 150 per-

sons, given the loss of at least one more upper level

and the destruction of the burial from the later intru-

sions.

Trying to reconstruct the sequence of events in rela-

tion to the mass burial, we can argue that an irregular

roughly dug pit was opened in the north-western

edge of the cemetery of Kerameikos - or the Erida-

nos cemetery as it is also known - destroying earlier

5

The child burials are marked in the plan in grey [fig. 3].

r

!

A mass burial from the cemetery of Kerameikos

+

Figure 3. Plan of the mass burial in Kerameikos (child burials in grey).

191

E. Baziotopoulou-Valavani

graves. A great number of bodies were thrown in it

one upon the other rather than buried; their positions

and orientation were dictated by the shape and the

size of the pit as well as by the large number of the

deceased, with more proper care shown at the begin-

ning, and far less later. Starting the burial, there was

an effort to throw some soil upon the dead. But after

two layers even this practice was abandoned and the

people were thrown one upon the other. A few in-

fants were also buried in the communal grave but

with more respect and piety.

6

Very few common,

offerings followed the deceased. A mass burial had

thus been completed in a hasty and improper manner

in a very short period of time. The dead might have

been covered by a low tumulus, for practical and not

monumental purposes, of which however nothing

remains.

7

The grave offerings

The grave offerings consisted solely of Attic pottery.

No other small objects or jewellery accompanied the

dead of the mass burial. Of the pots discovered in the

grave, we shall present the ones which are better pre-

served and those which provide chronological data:

Black-glazed cup

Inv.no. A 15285; Height: 0.075 m; Rim diameter:

0.083 m; Body diameter: 0.08 m [pi. 41A].

Mended. One handle missing. Chips and flakes,

mainly on the upper half of the body. Slight groove

around the middle of the body. Broad ring base.

It is similar to the cup of grave 224 (SW 101) in the

Kerameikos,

8

dated to 460/50 BC, and to the cup 343

from the Athenian Agora dated to c. 450 BC.

9

See

also the cup no. 13 from Rhodes in Copenhagen

10

and a rather larger cup of the same shape in Oxford.

11

Third quarter of the 5th century.

6

For the social aspects related to infant death in antiquity, see

among others R. Garland, The Greek Way of Death (lthaca 1985),

82.

7

As in 'other cases in the cemetery of Kerameikos (cf. the

Rundbau, GrabhUgel G and SUdhUgel) a circular pit follows the

contours of a tumulus in the way of the position of the dead, which

creates a cir.cle on the fringe of the pit. See C. H. H o u ~ y Nielsen,

"Burial language' in Archaic and Classical Kerameikos',

Proceedings of the Danish Institute at Athens I (1995), 129-184,

esp. 153.

8

U. Knigge, Der Siidhiigel (Berlin 1976), pi. 36.5.4.

9

Talcott, 'Stamped Ware', fig. 1,21.

10

CVA Copenhagen (5) Ill, pi. 176, 13.

11

CVA Oxford (2), pi. 65, 15.

192

Black-glazed lidded pelike

Inv.no. A 15282; Height: 0.15 m; Body diameter:

0.082 m; Height of lid: 0.03 m; Diameter of lid:

0.096 m [pi. 41B].

12

Mended. Both handles and a part of the lid are miss-

ing. Chips and flakes. Continuous curve from the

neck to the discoid base. The rim of the lid is rather

tall, with convergent walls.

The pelike belongs to the third class of the Athenian

Agora and is generally dated in the second half of the

5th century.

13

Similar vases are a pelike in Copenha-

gen from Athens and two others from Rhodes.

14

Second halfofthe 5th century.

Two black-glazed kothons

a. Inv.no. A 15264; Height: 0.08 m; Body diameter:

0.087 m.

b. Inv.no. A 15286; Height: 0.084 m; Body diameter:

0.082 m.

15

Both are mended. Parts of the body and the handle of

kothon a are missing. Chips and flakes. Vase b is

better preserved. The two-part vertical handle begins

at the rim and ends on the shoulder. A thin band with

relief dotting sets off the joint of the neck and the

body. Flat base with black concentric circles under-

side.16

Several similar vases, better known as Pheidias' cup,

were found in the grave enclosure of Hegeso in the

Kerameikos, dated in the third quarter of the 5th

century;

17

in the grave of Korkyraian proxenoi of

43312/

8

and in the Thespian polyandrion of 424

BC.l9

Third quarter of the 5th century.

Three black-glazed ribbed lekythoi

a. Inv.no. A 15260; Height: 0.111 m; Body diameter:

0.067 m; Base diameter: 0.055 m [pi. 41C].

b. Inv.no. A 15262; Height: 0.086 m; Body diameter:

0.053 m; Base diameter: 0.043.

c. Inv.no. A 15263; Height: 0.0455 m; Body diame-

ter: 0.048 m; Base diameter: 0.041 m.

a. Lekythos a is complete and preserved in good

condition. Calyx-shaped mouth, rather elongated

body, broad ring base, strap handle; it belongs to

12

See also CbC, 351, n: 383.

13

Agora Xll, 50.

14

CVA Copenhagen (I) Ill, pi. 176, 1-2; Clara Rhodos 11, 141 fig.

19 and Ill, 207 fig. 204.

15

The vase is illustrated in CbC, 353 no. 390.

16

For these vases see also CbC, 356, no. 390, commentary.

17

K. KUbler, 'Ausgrabungen im Kerameikos 1', AA 1938, 586-

606.

18

U. Knigge, 'Untersuchungen bei den Gesandtenstellen im

Kerameikos zu Athen', AA 1972, 584-629.

19

Schilardi, 166 ff, no. 75 pi. 19.

~

I

I

.l

; .

Rudolph's type VI E.

20

The shallow and thin grooves

form broad petals.

Ribbed lekythoi are quite common in the last quarter

of the 5th century, although their production starts in

the third quarter of the century?

1

Parallels to

lekythos a are: lekythos no. 358 from Thespiae;

22

the

lekythos from the child burial hs 168 in the

Kerameikos;

23

the ribbed lekythos 6-7 in Mainz;

24

and lekythos 197 in the Kieseleff Collection in

Wiirzburg with thicker petals?

5

The last two exam-

ples are dated in the last quarter of the century. Com-

pare also: four lekythoi from the Vassalaggi ne-

cropolis/6 dated to 430/20 BC and the third quarter

of the century.

b. Lekythos b is smaller than a, with broad, light

grooves forming vertical triangles around the body.

The handle and part of the calyx-mouth are missing.

The base is reserved.

Similar vases are known from burial hs 111 in the

Kerameikos cemetery, dated to the beginning of the

last quarter of the 5th century/

7

from grave 66 (56)

in the Syntagma cemetery/

8

and from a child sar-

cophagus from Voula. The latter is placed by

Schilardi in the early chronology of the type, at the

very beginning of the last quarter of the 5th cen-

tury.29

c. The upper part of the vase, mouth, neck and handle

of lekythos c are missing. Its shape is rather similar

to lekythos b.

c. 430 BC.

Black-glazed squat lekythos (with reserved band)

Inv.no. A 15258; Height: 0.092 m; Body diameter:

0.074 m; Base diameter: 0.062 m [pi. 41D].

The body is nearly cylindrical, with some chips and

flakes on its surface. The mouth, neck and handle are

missing. Ring broad base preserved. A reserved band

with the 'running-dog' motif adorns the front side,

under the shoulder. This shape is very popular in the

last third of the 5th century.

30

It belongs to Rudolph's

type VI E,

31

dated between 440-425.

The closest parallels of this lekythos are: the vases

from a well in the Athenian Agora (no. 53) dated in

20

Rudolph, 30-32, pi. Xill.

21

Agora Xll, 154.

22

Schilardi, 406, no. 358.

23

Schltirb-Viemeisel, 38 no. 71.pl. 38.5.

24

CVA Mainz, pi. 50,6-7.

25

Die Sammlung Kieseleffin Wiirzburg ll (1989), 121, no. 197, pi.

81.

26

NSC 1971 (suppl.) e,f,g,h, on 28, 47, 56, 84.

27

Schltirb-Viemeisel, 40, no. 78.

28

S. Charitonides, ''Avumccupul. KA.acrucrov 1:cuprov 1tapa 'ti)v

7tAU'tEiuv I.UV'tCx"fiJ.U'toc;', AEphem 1958, 59-60, fig. 101.

29

Schilardi, 406.

30

Agora Xll, 153-154.

31

Rudolph, 30, pi. Xill.

193

A mass burial from the cemetery of Kerameikos

440-425 BC;

32

and a lekythos in Geneva (no. 1302),

dated generally in the second half of the 5th cen-

tury.33 Other similar lekythoi are known from Thes-

piai (nos 356, 357) dated in 440-430 BC,

34

and from

cremation 39 in the cemetery of Anagyrous, dated by

Petrakos to the middle of the 5th century.

35

440-425 BC.

Black-glazed squat lekythos

Inv.no. A 15259; Height: 0.074 m; Body diameter:

0.069 m; Base diameter: 0.057 m.

It is similar to lekythos A 15258, with more rounded

body. Mouth, neck and handle are missing. Many

chips on the surface. On the front side, a reserved

band, covering the upper body, is decorated with a

series of careless 'S'. Ring broad base, reserved in its

lower part.

The shape of this lekythos belongs to Rudolph's type

VI A, dated between 440 and the third quarter of the

5th century.

36

An exact parallel was found in grave

370 in the Kerameikos dated in the third quarter of

the 5th century.

37

Other similar examples from the

same cemetery were found in burial 75 (lamax hs

112) dated to c. 440-430/

8

and burial 66 (hs 160)

dated to 440 BC.

39

440-425 BC.

Black painted squat lekythos

Inv.no. A 15276; Height: 0.066 m; Body diameter:

0.039 m; Base diameter: 0.031 m.

The body is complete. Parts of the mouth, neck and

handle are missing. The rather rectangular body is

decorated with two reserved bands with pairs of

black stripes. Ring base.

Similar to the form and style is a lekythos in Geneva,

dated in general terms in the 5th century.

40

Similar

better dated examples are known from Athens, one

from cremation IV, of 430 BC,

41

and the other from

'Brandgrab' 81 in the Kerameikos, accompanied

with six white-ground lekythoi of 420-410 BC.

42

430-420 BC.

32

Talcott, 'Stamped Ware', 477-523, fig. 1.53.

33

.CVA Geneve (1) ill L, pi. 24.10. .

34

Schilardi, 402, pi. 47.

35

B. Petrakos, ADelt 20 (1965) B1, 115, pi. 81p.

36

Rudolph, 28, pi. Xll.4-5.

37

Kerameikos Vll.2, 96, pi. 63.7.

38

Schltirb-Viemeisel, pi. 38.5.

39

Ibid., pi. 29.2.

4

CVA Geneve (1) ill,1 pi. 23.13.

41

D. Schilardi, AvaO"Icaqn'J 1tapa 1:a MaKpa TEiXTJ Kat f)

oivox6TJ 1:oii Tuupou', AEphem 1975, 78-80, pi. 35a.

42

Schlorb-Viemeisel41, Beil. 30.2 (cremation hs 173.7).

E. Baziotopoulou- Valavani

l

Three white-ground pattern lekythoi

a. Inv.no. A 15271; Height: 0.153 m; Body diameter:

0.057 m; Base diameter: 0.042 m.

The upper part of the vase (mouth, neck and handle)

is missing. Chips and flakes on the surface.

b. Inv. no. A 15277; Height: 0.134 m; Body diame-

ter: 0.045 m; Base diameter: 0.032 m.

The mouth is missing. Many chips and flakes on the

surface.

c. Inv. no. A 15279; Height: 0.116 m; Body diame-

ter: 0.051 m; Base diameter: 0.036 m [pi. 42A].

Mouth, neck and handle are missing. Chips on the

surface.

The three white-ground pattern lekythoi are deco-

rated on the body with ivy-berry tendril. framed by

latticework, a motif generally associated with the

Beldam Painter's Workshop; on the shoulder stripes

and dots. This decorative schema seems to have been

most popular in the second half of the 5th century.

43

Similar lekythoi were found in the graves of the

Korkyraian proxenoi (433/2 BC)

44

and in graves 418

(440-430 BC) and 489 Gust before 430 BC) in the

Kerameikos.

45

c. 430BC.

Two red-figure squat lekythoi

a. Inv.no. A 15265; Height: 0.112 m; Maximum

diameter: 0.065 m; Base diameter: 0.05 m.

46

Complete, with few chips. The mouth is calyx-

shaped, the body is elongated cylindrical, and the

ring base is broad. Strap handle. A female figure,

standing on a reserved band, is shown in profile to

the left. She wears a chiton and himation and her hair

is gathered in a bun, leaving her earring to show.

With her extended right hand she holds a piece of

cloth.

b. Inv.no. A 15270; Preserved height: 0.093 m.;

Maximum diameter: 0.066 m; Base diameter: 0.066

m [pi. 42B].

The mouth is missing. A few flakes on the surface.

Similar in shape to a. A female figure shown in pro-

file to the left is depicted in the same style and man-

ner as the one on lekythos a. She offers a libation

over an altar.

The shape belongs to Rudolph's type VI A

47

and is

dated to 440-425 BC. In terms of style, squat

. lekythoi A 15265 and A 15270 belong to Sabetai's

43

Kurtz,AWL, 154.

44

Knigge, op.cit. n. 18.

45

Kerameikos VII.2, 106-107, pi. 70.2 and 129, pi. 88.1. For

similar pattern Iekythoi see Kurtz, AWL, 154, 231, pi. 70.7. See

also CVA Mainz (1) pi. 37.8, dated from the middle to the third

quarter of the 5th century.

46

The vase is illustrated in CbC, 353 fig. 388.

47

Rudolph 28, 90, pi. Xll, 4,5.

class SL

48

and are dated to 430-420 BC. The iconog-

raphy is usually related to f:7Ca.v2w or yvva.ucmvir11r;

scenes.

49

c. 430BC.

Red-figure squat lekythos

Inv.no. A 15283; Height: 0.069 m; Body diameter:

0.068 m; Base diameter: 0.055 m [pi. 42C].

Mended, with some chips and flakes. The mouth,

neck and handle are missing. The body is squat

globular and the ring base is broad. A sphinx, seated

on a band with an Ionic pattern, is concentrated on

reading a stele. Its left toe is lifted.

The shape is similar to vase no. 12404 in Geneva,

50

dated in the last quarter of the 5th century. Fairly

similar is another squat lekythos in Zurich,

51

in the

manner of the Washing Painter.

The subject of the seated sphinx is very common but

the reading sphinx is not very usual. For the subject,

though of different shape and style, see lekythos no.

105 from the Purification ofDelos (426 BC).

52

430-420BC.

Red-figure squat lekythos

Inv.no. A 15269; Height: 0.087 m; Body diameter:

0.067 m; Base diameter: 0.049 m [pi. 42D].

The mouth and the strap handle are missing. The

body is rather globular, the ring base is broad. A

Nike, standing on a reserved line to the right, holds

with her right hand a tendril bud. The shape belongs

to Rudolph's type VI A.

53

The subject is very com-

mon in the second half of the century. The style of

the Nike is very close to the female figure dressed in

chiton and himation, on the kotyle no. 120 from a

well in the Athenian Agora,

54

dated in the decade of

430BC.

440-430 BC.

48

V. Sabetai, The Washing Painter: a Contribution to the Wedding

and Gender Iconography in the 2nd half of the 5th cent. B. C. (Ann

Arbor 1993), 212-213.

49

See A. Lezzi-Hafter, Der Eretria Maler (Mainz 1988), pi. 124,

197c; CVA Torino (3) m, 1, pi. 1Z,4 and CVA Zurich (1) ill pi. 24,

11-12 for a similar lekythos related to the group of the Washing

Painter. See also the squat lekythos 167 in the Kieseleff collection

in Wiirzburg, which seems to be close in style to the two squat

lekythoi of the mass burial.

5

CVA Geneve (1) m, 1 pi. 22,6.

51

CVA Zurich (1), m, 1 pi. 24, 13-14.

52

Ch. Dugas, EAD XXI: Les vases attiques a figures rouges (Paris

1952), pi. XL, 105.

53

Rudolph 28, 90 pi. Xll 4,5.

54

Talcott, 'Stamped Ware', 492 fig. 12.

1 eoea

194

Red-figure squat lekythos

Inv.no. A 15268; Height: 0.061 m; Body diameter:

0.048 m; Base diameter: 0.035 m.

Almost complete; the mouth neck and strap handle

are missing. Several flakes on the surface. Ring base.

The body is fairly rounded rectangular. A Nike,

walking to the left, is holding a jewellery box

(pyxis). A basket (kalathos) is depicted in front of

her. The shape of the vase is close to Rudolph's type

11 C,

55

dated in 470-450/40 BC.

Although the subject is very common, no exact par-

allel is known to me; for a close but older example,

see no. 2690 in Mainz,

56

attributed to the Seireniske

Painter. There is a lekythos in Copenhagen, which is

similar in shape and subject but not in style. 5

7

Last quarter of the 5th century.

Red-figure lekythos of secondary type

Inv.no. A 15281; Height: 0.17 m; Shoulder diameter:

0.068 m; Base diameter: 0.05 m [pi. 43A].

58

The neck, the mouth and the strap handle are miss-

ing. Chips and flakes. The body, almost cylindrical,

stands on a discoid base.

A departure scene is depicted on the main side of the

vase. On the left, a woman, wearing a peplos, holds a

phiale in her right hand. The young man opposite

her, dressed as a traveller with petasos and chlamys,

is holding a spear, which forms the axis of the scene.

The scene is crowned by a meander band whereas a

reserved band serves as the ground line. On the

shoulder there are three black palmettes, the central

reserved, enriched with volutes.

The subject, the departure of the man from home, is

very popular in the iconography of the 5th century. A

similar subject is depicted on the tondo of a kylix by

the Calliope Painter, dated in the third quarter of the

5th century. 5

9

The female figure, especially the rendering of her

head, is related to the woman on the lekythos 12343

in Basel, which is attributed to the Klugmann

Painter.

60

Lekythos A 15281 can also be attributed to

the workshop of the Kliigmann Painter and it is

probably a late work of the painter himself.

61

c. 430 BC.

55

Rudolph, 18 pi. IX.3.

56

CVA Mainz (4), pi. 53, 7-9.

57

CVA Copenhagen (5) m, 1 pi. 167, 6.

58

For the lekythos A 15281 see CbC, 355, no. 387.

59

Lezzi-Hafter, op.cit. n. 49, pi. 66a.

6

CVA Base! (3) m, pis 30.3-4, 33.2.

61

For Kliigrnann Painter see ARV

2

, 1198-1200, 1686; L. Zoroglu,

'Zwei Lekythoi Kliigrnann-Malers a us Kelenderis', AA 1999, 141-

145.

195

A mass burial from the cemetery of Kerameikos

Red-figure chous

Inv.no. A 15284; Maximum height: 0.072 m; Body

diameter: 0.083 m [pi. 43C].

Only the front side of a chous is preserved. Mended

from three sherds. A boy is sitting on his toy-cart

offering a cake, n-6n-avov. A chous is depicted in

front of him. The scene could probably be completed

to the right with another boy pushing the toy-cart.

The figures stand on a band decorated with an Ionic

pattern. The same pattern is discerned above the

scene, at the top of the fragment.

The scene includes the main symbols of the third day

of the Anthesteria festival and can thus be considered

as one of the numerous representations of this popu-

lar subject on choes. The child seated on the cart is

not a usual subject on choes.

The contour of the child's face, his deep-set eyes, his

heavy chin and his backward pose [pi. 43D], can be

paralleled with the Eros riding on a deer, on a large

squat red-figure lekythos in Tubingen,

62

which has

been attributed by J. Burow to Polion and dated to

430 BC.

63

Red-figure chous

Inv.no. A 15272; Height: 0.066 m; Maximum di-

ameter: 0.064 m; Base diameter: 0.049 m.

64

Mended. The handle is missing; few chips on the

surface. Trefoil mouth, with the middle lobe slightly

larger than the others, globular body, broad ring base.

The scene is bordered on both ends by bands with

Ionic pattern. Two facing boys are playing with rib-

bons on the edge of which a ball is attached. They

are wearing _bands on their heads and periamma on

their chests. Between the children, in the middle of

the scene, two Maltese dogs are participating in the

game.

The most interesting feature of this chous is the chil-

dren's game, which is depicted here for the first

time.

65

The boys hold a strap or a rope with a ball

fastened to its end. They either hurl the ball as far as

they can, or throw it in the air by holding the strap by

the end. The dogs participate in the game, trying to

catch the balls.

66

The closest parallel in terms of iconography is a vase

from a rescue excavation at Aiolou Street in Ath-

ens.

67

Similar in style is the chous from Athens in the

62

CVA Tiibingen (5), pi. 44,3-4.

63

For Polion see ARV

2

1171-3 and 1685. See also AR 1960-1961,

58 n. 23, fig. 11.

64

The vase is illustrated in CbC, 351, 356 no. 389.

65

For children's games see E. Schrnidt, Spielzeug und Spiele der

Kinder in klassischen Altertum (Meiningen 1971).

66

For this vase in particular but also for bibliography on choes see

CbC, 355-356 no. 389.

67

ADelt 18 (1963) B1, pi. 32cS.

E. Baziotopoulou-Valavani

British Museum (no. 1929.10-16,2) attributed to the

Group of Athens 12.144.

68

Last quarter of the 5th century.

About 15 white-ground lekythoi and lekythoi frag-

ments were found in the mass burial. In most cases

the figure decoration is partly or totally effaced. The

better-preserved examples are described below. All

of them belong to the same type with the calyx-

shaped mouth, a rather tall neck, sloping shoulder

and the 's' outline from the lower body to the low

disc foot. The lekythoi can be thus dated to the very

end of the third and the beginning of the last quarter

of the 5th century.

69

White-ground lekythos

Inv.no. A 15293; Preserved height: 0.29 m; Shoulder

diameter: 0.084 m (0.054 m) [pL 43B].

The foot is missing; mended with restored parts. Sur-

face worn, faded matte red paint.

On the shoulder is depicted a floral pattern of pal-

mettes with alternating matte black and red leaves,

enhanced with tendrils. Under the shoulder there is a

band of meander running right. On the body of the

lekythos, the centre of the scene is occupied by a

slender stele, on a two-stepped base, decorated with a

large four-leaf pattern, which has a pair of antithetic

s-shaped volutes on its centre. On the left, a woman

dressed in a belted peplos is walking towards the

stele, holding, in her right hand, a torch with hanging

ribbons. Her left hand is hidden by the grave monu-

ment. The young man on the right, dressed in travel-

ler's costume, is leaning against the tomb monument

with his right arm; he holds two spears in his left

hand.

70

The young man is similar to the male figure on

lekythoi 535 and 536 in Frankfurt.

71

The style and

the clothes are close to the male figure on lekythos

71 in Tokyo.

72

The woman is similar in style and

rendering to the female figure on the white-ground

lekythoi 14515 and 1848 in the National Archaeo-

logical Museum in Athens,

73

as well as to the woman

on lekythos 334 in Palermo.

74

They are all attributed

to the Reed Painter. For the unusual tetrafoil orna-

6

s ARV

2

1320 1

69

The shape 'is .close to that of.Rheneia's white-ground lekythoi.

Kurtz, AWL, 132 no. 9.

7

For this vase and the details of its style see: CbC, 352-353 no.

385.

71

CVA Frankfurt (4), 40 pi. 20,1-23;7. See also the male figure on

the lekythos no. A 7 of the British School at Athens, in J. Oakley

and E. Langridge-Noti (eds), Athenian Potters and Painters.

Catalogue of the Exhibition (Athens 1994), 55-56, no. 40.

72

CVA Japan (2), no. 71,22 pi. B7 and 17,9.

73

Papaspyridi, 117-146.

14

CVA Palermo, no. 334, pi. 8, 1-2.

196

ment see the lekythos 1897, 172 c in Glasgow, which

is a work by the same painter.

75

This pattern cannot

represent an existing fmial, thus confirming the

scholars who believe that white-ground lekythoi of

this period often represent an imaginary rendering of

the grave.

76

Lekythos A 15293 is attributed to the Reed Painter,

whose main period of production is believed to be

420-410 BC. Except for the painter's style, the attri-

bution is confrrmed by one of his 'signs': the hiding

of the hand behind a monument, structure or figures

is a common trick of the painter's hasty work.

77

c. 420BC.

White-ground lekythos

Inv.no. A 15301; Preserved height: 0.205 m; Shoul-

der diameter: 0.68 m [pi. 44A].

Mouth and foot are missing. Flakes on the surface.

Much of the painting is faded.

The male figure on the left is bending towards a

grave monument, obviously a stele. The stele is close

to Nakayama's group AIV, especially AIV 33, dated

between 435 and 420 BC.

78

The young man seems to

give offerings to the grave. There are no visible

traces of the right figure of the scene.

The young man is quite similar to the left figure on

lekythos 334 in Palermo,

79

though the work on our

lekythos is more hasty. The face of the young man is

similar to that on the lekythos in Tokyo.

80

Lekythos

A 15301 can therefore be attributed to the Reed

Painter.

81

White-ground lekythos

Inv.no. A 15302; Preserved height: 0.202 m; Maxi-

mum diameter: 0.07 m; Base diameter: 0.05 m [pi.

44B].

The mouth, the upper part of the neck and the handle

are missing. Chips and flakes, faded colours. Paint is

destroyed on parts of the surface. Cylindrical body

on a disc foot. The scene is crowned by a band of

meander running towards the right.

75

CVA Great Britain (18) The Glasgow Collection, 34 pi. 33, 5-7.

76

See for example H.A. Shapiro, 'The Iconography of Mourning

in Athenian Art', AJA 95 (1991), 655. One could consider several

possibilities for this four-leaf pattern. A possible suggestion was

made by Prof. N. Stampolidis, who proposed that it is a depiction

of a trophy consisting of shields.

77

On the Reed Painter see ARV

2

1376-1382, 1692, 1704; Para

485, 524; Addendd 370; Kurtz, AWL, 58-68; Papaspyridi; Felten,

'Lekythen', 77-113; Oakley and Langridge-Noti, op.cit. n. 71, 55-

56 for more bibliography.

?s N. Nakayama, Untersuchungen der auf weissgrundigen

Lekythen dargestellten Grabrniiler (Freiburg 1982), 65 pi. 9.

79

CVA Palermo, no. 334 pl. 8,1-2.

8

CVA Japan (2), 22, pi. B7.

81

For the Reed Painter and white-ground lekythoi in general see

above note 77.

..,

Two women by the grave. A stele on a two-stepped

base with a three-part finial at the centre of the scene.

On the left stands a young woman wrapped in a hi-

mation, with her head bent low. Opposite her another

woman, depicted in three-quarter view, is dressed in

a yellow peplos. Traces of red ribbons are visible on

the stele and on the first and third part of the finial.

The grave stele belongs to Nakayama's type AV2,

dated in the last quarter of the 5th century.

82

For the

figure on the right see parallels in Copenhagen,

83

and

for the head of the female figure on the left see

lekythos no. 19273 in the National Archaeological

Museum in Athens.

84

For this figure see also the

lekythoi from Argos, in Japan and in Berlin.

85

Lekythos A 15302 is a work of the Reed Painter. The

liasty work and the concealed hand of the woman

behind the stele on the right are characteristic of his

work. The child-like figures recall the style of the

Bird Painter, with whom the Reed Painter is stylisti-

cally connected.

86

c. 420BC.

White ground lekythos

Inv.no. A 15295; Preserved height: 0.18 m; Maxi-

mum diameter: 0.067 m; Base diameter: 0.057 m [pi.

44C].87

The neck and the handle are missing. Chips and

flakes on the surface. Part of the painting and added

colours have disappeared. On the upper part of the

body a faded meander outlined by lines of dilute

glaze, crowns the scene.

Man and woman by the grave. At the centre, a rec-

tangular stele with acanthus finial. On the left, a male

figure leans on a spear, and on the right a female

figure holding a kanistron is bending towards the

grave to lay an offering. Her right foot rests on the

step of the stele base.

The style of this lekythos is quite different from the

above. Its figures can be equally related to the circle

of the Painter of Munich 2335 and to the Bird

Painter. The relation of the two painters has been

confirmed archaeologically and stylistically.

88

The young man bears similarities to a figure on a

lekythos in Berlin, attributed by I. W ehgartner to the

Painter of Munich 2335.

89

The woman is similar to

the kneeling young lady on the lekythos 3832 from

82

Nakayama, op.cit. n. 78, 62, fig. 6lg, pi. 10.

83

CVA Copenhagen (5) ill, 1 pi. 173, 3a-b.

84

Chr. Kardara, 'Four White Lekythoi in the National Museum',

BSA 55 (1960), 149-158, esp. 158, pis 40-41.

85

Papaspyridi, 122 fig. 6a; CVA Japan (2), pi. 87 and CVA Berlin

(8), pi. 17,1-2.

86

Kurtz, AWL, 58.

87

For the vase see CbC, 353-355, no. 386.

88

Kurtz, AWL, 53-54.

89

CVA Berlin (8), pi. 17, 1-2.

197

A mass burial from the cemetery of Kerameikos

the Kerameikos, attributed to the Bird Painter.

90

The

bad state of preservation of the surface does not per-

mit a more detailed stylistic approach; yet, lekythos

A 15295 can be attributed to the circle of the Bird

Painter.

White-ground lekythos

Inv.no. A 15300; Height: 0.031 m; Rim diameter:

0.057 m; Body diameter: 0.893 m.

Mended. The foot is missing. Chips and flakes.

Faded colours, parts of the white ground are lost.

On the left, a seated male figure can be discerned

with much difficulty. In the middle, a rectangular

stele is depicted crowned by a finial, which is hard to

discern. A woman stands on the right. Only the upper

part of her head and her long himation are preserved.

The style of the woman recalls the work of the

Painter of Munich 2335 as she can be easily related

to the painter's female figures. For an example from

the same cemetery, see the woman's head oflekythos

inv. no. 1965 in the Kerameikos.

91

Lekythos A 15300

may be a later work of the Painter himself or attrib-

uted to his Group.

92

c. 430BC.

White-ground lekythos (secondary type)

Inv.no. A 15296; Height: 0.162 m; Maximum di-

ameter: 0.062 m [pi. 44D].

The mouth and the foot are missing. Chips and

flakes. Parts of the white ground are missing. Only

some lines of the decoration, in shiny gilded brown,

are preserved. The scene, visit to the grave, is

crowned by a meander band, running towards the

right. On the reserved shoulder there are faded traces

of tongue-pattern. Only parts of the left figure,

probably a woman, are still visible; her two hands

tend to the stele and with her right she offers a

wreath. A triangular finial on the top of the stele can

be easily discerned.

to the shape, this vase belongs to Kurtz's

type

which is connected with the Aeschines'

and Tympos Painters. The decoration, however, is

very 'frairoentary'. Lekythos A 15296 seems to be

connecteq to an artist close to the Tymbos Painter

and to the Group of Athens 2025; this attri-

bution is mainly based on the shape and style of the

meander band and of the woman's hands. The scene

9

K. Athusaki, 'Drei weissgrundige Lekythen', AM 85 (1970}, 49-

52, pi. 21,1.

91

Felten, 'Lekythen', 94, cat. no. 29, pi. 30.1.

92

For the painter of Munich 2335 see ARV

2

1161-70, 1685, 1703,

1707; Kurtz, AWL, 22, 55-56; M. Tiverios, Ilepiclsw Jlava81jva10..

Eva<; KpaU,pa<; wv Zwyprl.rpov Tov Movrl.xov 2335 (Thessaloniki

1989), 89-100.

93

Kurtz,AWL, 82-83.

E. Baziotopoulou-Valavani

resembles that of the white-ground lekythos 1113 in

the Kerameikos, attributed to the late circle of the

Tymbos Painter.

94

See also lekythos no. 1875 in the

National Archaeological Museum in Athens.

95

c. 440BC.

Among the finds were two sherds of white-ground

lekythoi. On the first, the upper body of a male figure

is depicted; it can be attributed to the Reed Painter.

The second, depicting a head of a man wearing a

petasos, is probably the work of the Woman Painter.

There is similarity in execution with the left figure on

the white-ground lekythos 2 from grave 583 in the

Kerameikos, attributed to the 'Frauenmaler'.

96

Chronology

According to the accepted chronology, the majority

of the vases from the communal grave is d a t e ~

around 430, some can be dated within the decade of

420 BC and a few generally in the last quarter of the

5th century. Yet, the hasty and impious way of the

inhumation of about 150 people, who probably re-

ceived no proper funeral rites, indicates the panic of

the persons who buried them. The strange way of

burial, as well as the chronology of the few common

vases in the decade of 420 BC inevitably has to be

associated with the plague in Athens in the first years

of the Peloponnesian War, between 430-426 BC.

The contagious disease erupted in Athens suddenly;

the shadow of panic slid over the entire population.

Many scholars and doctors in particular have tried to

identity the illness with known diseases such as

small pox, bubonic plague, scarlet fever, measles,

typhoid fever, ergotism and recently ebola.

97

It seems

possible, however, that this disease is either extinct

94

Felten, 'Lekythen', pi. 26,3.

95

Athusaki, op.cit. n. 90, pi. 19,2.

96

Kerameikos Vll.2, 145, pi. 95.3.

97

In general see D.L. Page, 'Thucydides' Description of the Great

Plague at Athens', CIQ 3 (1953), 97-119; A. Parry, 'The Language

ofThucydides' Description of the Plague', BICS 16 (1969), 106-

118; V. Nutton, 'The Seeds of Disease: an Explanation of

Contagion and Infection from the Greeks to the Renaissance',

MedHist 27 (1983), 1-34; E.D. Phillips, Greek Medicine (London

1973); J. Poole and A.J. Holladay, 'Thucydides and the Plague of

Athens', CIQ 29 (1979), 282-300. See also by the same authors,

ClQ 32 (1982), 235; ClQ 34 (1984), 483-485 and A.J. Holladay,

ClQ 38 (1988), 247-250; J. Longrigg, 'The Great Plague of

Athens', History of Science 18 (1980), 209-225; A.D. Langmuir,

et al. (eds), 'The Thucydides Syndrome', New England Journal of

Medicine 313 (1985), 1027-1030; J. Longrigg, 'Death and

Epidemic Disease in Classical Athens', in V. Hope and E.

Marshall {eds), Death and Disease in the Ancient City (London

and New York 2000), 55-64.

198

or so mutated, that it could not be recognised from

the symptoms described by Thucydides (ii.47.3).

98

The mass burial in the Kerameikos offers the ground

for a medical approach through the study of the hu-

man bones that were collected from it.

99

If we find

remains of a disease, then not only the attribution of

the burial to the great plague of Athens will be con-

fmned but the medicine historians may also connect

a certain disease to the plague.

There is a chronological disparity of 5-6 years be-

tween the accepted chronology of some of the vases

- based mainly on style - and the historical event of

the Athenian plague. The main difficulty arising

from its attribution to the plague described by Thu-

cydides is related to the career of the Reed Painter. It

is generally accepted that he had worked in the last

quarter of the 5th century at the earliest. The Reed

Painter's white-ground Iekythoi, however, were

found together with vases of the Kliigmann Painter,

Potion and the Bird Painter. The question is whether

the beginning of the Reed Painter's production

should be placed about five years earlier and thus be

contemporary with his related colleagues, the Bird

Painter, the Painter of Munich 2335, or the workshop

of the Tymbos Painter. We face again a similar

situation of chronology to the one of the two sar-

cophagi of Anavyssos, where vase painters believed

to have worked in different periods proved to be

contemporary.

100

Yet, many scholars agree with

McDonald's comment: "Still, although history can

help to refine our knowledge of pottery, the reverse

is not always true and one must be careful in using

pottery to supplement historical data".

101

But in the

case of the mass burial in Kerameikos, pottery and

historical data are in agreement.

Kurtz and Boardman, based on literary sources, have

already accurately mentioned that the few examples

of mass burial in the Classical period were the results

of extreme circumstances, such as the second out-

burst of the plague in 427/6 BC.

102

Although no other

mass burials due to epidemic diseases have been ex-

cavated in Athens to date, mass burials of the 5th

98

Rhodes, Thucydides, 228-229.

99

Associate Professor M. Papagrigorakis, who studies the 'bones of

the mass burial in collaboration with Professor A. Koutselinis of

the University of Athens, is in the process of examining the human

remains for DNA and RNA.

100

B. Petrakos, ADelt 16 (1960) B, 39; S. Oakley, 'A Red-figure

Workshop from the Time of the Peloponnesian War', BCH Suppl.

23 (1992), 199.

101

B.R. McDonald, The Distribution of Attic Pottery from 450 to

375 B. C. The Effects of Politics on Trade (PhD Thesis, University

ofPennsylvania 1979).

102

Kurtz and Boardman, 97.

l

' f.

century are known in Attica, and central Greece.

103

A

mass burial was recently excavated in Pydna (Mace-

donia). In a rectangular shaft grave 120 deceased,

men, women and children, had been buried in disor-

der in four layers. There were no offerings but the

burial has been dated in the 4th century BC.

104

The mass burial of Kerameikos is different from the

known common burials of the Phaleron captives,

who though unaccompanied by offerings, were nev-

ertheless buried one beside the other in a normal in-

humation.105 The same method of burial occurred in

other communal burials or in state burials, such as

the Thespian Polyandrion for the dead of the Battle

at Delion in 424 BC,

106

in the Lakedaimonians' grave

in Kerameikos,

107

as well as in three burials in Olyn-

thos,108 containing 9, 9 and 26 persons respectively;

Robinson - based on the normal way of their burial -

considered them as victims of the battles of 432 or

428 BC rather than of the plague, which, according

to Thucydides (ii.58.2), had broken out in the

neighbouring Potidaia, in the Athenians' camp.

109

A typical testimony of an improper mass burial in

antiquity comes from Pausanias for the Persians who

fell in the Marathon battle:

Although the Athenians assert that they

buried the Persians, because in every case

the divine law applies that a corpse should

be laid under the earth, yet I could find no

grave. There was neither mound nor other

trace to be seen, as the dead were carried to a

trench and thrown in anyhow ... uo

In the 19th century the German captain von Eschen-

burg, in his book on Marathon, argued that in the

vineyard of Skouze a great number of human bones

were found, belonging to hundreds of dead, buried in

a disorderly fashion. The captain himself excavated

at the ridges of the vineyard and found that the entire

103

For multiple state burials or communal graves, see Kurtz and

Boardman, 108 and 247ff.

104

The excavation is going to be published; the information is

derived from the newspaper Kafh?pepmi 1-4-2001.

105

S. Pelekidis, ''AvaaiCaqn't cflaA.fipou', ADelt2 (1916), 13-64.

106

Schilardi, 19-28 and in particular for the communal graves: W.

K. Pritchett, The Greek State at WarN (Berkeley 1985), 125-139.

107

L.R. Van Hook, 'On the Lakedaimonians Buried in the

Kerameikos', AJA 36 (1932), 290-292; F. Willemsen, 'Zu den

Lakedaimoniergraber in Kerameikos', AM 92 (1977), 128ff.

108

D. Robinson, Olynthus XI: Necrolynthia (Baltimore 1942), 163;

Kurtz and Boardman, 257.

109

Robinson, op.cit. n. 108, 163ff.

110

Pausanias i.32.3-5. Translation by W.H.S. Jones, Loeb edition.

199

A mass burial from the cemetery of Kerameikos

region up to the swamp was full of bone remains,

coming out of the ground during cultivation.

111

For the 5th century, there is a fair amount of scat-

tered evidence for multiple burials in the same grave.

However, even in these few examples - all from

Athens and Attica - the number of the dead is not

more than three. Most of these burials published so

far

112

have been dated in the last third of the century;

moreover, they are also connected with a contagious

disease like the plague, which had attacked members

of the same family.

Some scholarsll

3

believe that in the years of the

plague the victims of the disease had been cremated,

thus making detection of multiple burials impossible.

This argument is derived from Thucydides' descrip-

tion that some people "btt 1t'llpa10 yQ:p aA.A.o'tpta!O

!pB<lcrav'tEIO 'tOU!O vf)crav'ta!O oi JlEV E1tt9EV'tEIO 'tov

mn&v veKpov il!pf\1t'tov" (ii.52.4). But some lines

above, the historian clearly states that "9a1t'tov 8 ro10

EKCXO''tOIO 8ilva'to. Kat 1t0AA0t EIO avatO'XUV'tO'Il!O Bf)Ka!O

1:pcX1tOV'tO" (ii.52.4).

Extreme emotions of fear and panic have been ex-

pressed in art and literature. Poetic, social, medical -

and even cinematic - references to disastrous plagues

have been made later, from Lucretius and Virgil to

. ll4

Camus' La Peste and Bergmann's Seventh seal.

Nevertheless, Thucydides' description of the plague

still remains one of the most vivid literary passages

on disaster and creates strong emotions even in the

modem reader. The historian, being struck by the

plague himself, narrates the events vividly and emo-

tionally (i_i.52.2-53):

LII. But in addition to the trouble under

which they already laboured, the Athenians

suffere(i further hardship owing to the

crowdiQg into the city of the people from the

country districts; and this affected the new

arrivals especially. For since no houses were

available for them and they had to live in

huts that were stifling in the hot season, they

perished in wild disorder. Bodies of dying

men lay one upon another, and half-dead

people rolled about in the streets and, in their

longing for water, near all the fountains. The

temples, too, in which they had quartered

111

V. Eschenburg, Topographische, archiiologische und

militiirische Betrachtungen auf den Schlachtfelde von Marathon

(1886); B. Petrakos, '0 Mapa8wv(Athens 1995), 25.

112

Kerameikos, Tavros, Heriai gate, in S.G. Humphreys, 'Family

Tombs and Tomb Cult in Ancient Athens. Tradition or

Traditionalism?', JHS 100 ( 1980), 11 Off.

113

Ibid.

114

J.S. Rusten (ed.), Thucydides. The Peloponnesian War II

(Cambridge 1989), 179-180.

E. Baziotopoulou-Valavani

themselves were full of the corpses of those

who had died in them; for the calamity

which weighed upon them was so overpow-

ering that men, not knowing what was to be-

come of them, became careless of all law,

sacred as well as profane. And the customs

which they had hitherto observed regarding

burial were all thrown into confusion, and

they buried their dead each one as he could.

And many resorted to shameless modes of

burial because so many members of their

households had already died that they lacked

the proper funeral materials. Resorting to

other people's pyres, some, anticipating

those who had raised them, would put on

their own dead and kindle . the fire; others

would throw the body they were carrying

upon one which was already burning and go

away.

LIIL In other respects also the plague first

introduced into the city a greater lawless-

ness.ll5

There was thus a total disruption of the traditional

rites to the dead since their suffering brutalised them;

being pious or impious made no difference, because

they saw that all perished equally and everyone ex-

pected to die before he paid legal penalties for his

crimes.

116

Even if we accept some scholars' scepticism refer-

ring to the historian's exaggeration,

117

it is corn-

mended that the society as a whole reached at the

time a depth of religious despair unparalleled in the

ancient Greek world.

No fear of gods or law of men retrained; for

seeing that all men were perishing alike,

they judged that piety and impiety came to

the same.U

8

It has been supported that the social changes that

occurred during and because of the Peloponnesian

War and the plague are reflected in the burials.

119

115

Translation C.F. Smith, Loeb edition, 351,353.

116

For literature, historical and medical comments see: S. Horn-

blower, Commentary on Thucydides I: Books I-ll (Oxford 1991),

chapters 47.3-53.1, 2-5, 97-100, 134; A.W. Gomme, A Historical

Commentary on Thucydides IT: Books IT-ill (oXford 1972),

ii.47.3-54.4; Rhodes, Thucydides, 228-233; J.S. Rusten, op.cit. n.

114.

117

J.D. Mikalson, 'Religion and the Plague in Athens, 431-423

BC', JHS 104 (1984), 219; Longrigg, op.cit. n. 97.

118

Thuc. ii.53; Smith, op.cit. n. 115, 353.

119

Thucydides believes not only that there was a collapse of

standards during the plague (ii.53.1), but also that the Athenians

did not return to the old standards afterwards. There is a contrast

between Athens, which was well prepared for the war both in

200

The plague broke out in Athens early in the summer

of 430 and continued until the summer of 428. After

a brief remission, it burst again in the winter of 427

until the winter of 426. It is assumed that l/3 of the

Athenian population perished from the contagious

disease. The dead near the temples, the sanctuaries,

the fountains and in the streets, whose relatives

'lacked the proper funeral material' and could not

afford to offer a proper burial, were gathered by the

state and were buried in a communal shaft grave at

the fringe of the cemetery of Kerameikos, under con-

ditions of panic. This mass burial is therefore a sort

of state burial. But this time the state does not honour

its dead soldiers of a vigorous battle. This time the

state buries the anonymous poor people in order to

protect the rest of its inhabitants from the plague.

120

Many archaeologists wonder about the absence of

archaeological evidence on the victims of the plague.

Until the data of the excavations of the cemeteries

are fully published, we cannot make any further hy-

potheses. Kiibler, Morris, Houby-Nielsen and other

scholars have argued that during the period of the

plague, the number of graves in the Kerameikos in-

terestingly enough reduced.

121

In our excavation we

cannot support this view since 80% of the graves

belong to the 5th century and span equally its two

halves. The same conclusion can be derived at pre-

sent from the recently excavated, unpublished large

cemetery in Amerikis Street, not far from Syntagma

Square.

122

manpower and other resources, and Athens which lost a third of its

manpower through a chance misfortune (ii.54.4). Rhodes,

Thucydides. See also Kurtz and Boardman, 97; I. Morris, Death-

Ritual and Social Structure in Classical Antiquity (Cambridge

1992), 140-141 and 154-155.

120

The mass burial of Kerameikos could possibly be related to

other historical events of the 5th century, namely the famine in

Athens during Lysander's besiege of the city from land and sea

mentioned in Xenophon's Hellenica (ii.2.10-13). The famine

caused the death of many people by the end of the war in 404 BC.

Still, the improper way of the inhumation in the mass burial and

the chronology of the offerings do not permit us to attribute it to an

extraordinary but accepted event such as this starvation but to an

event which created panic such as the plague. On the other hand, if

the mass burial had taken place at the end of the century, then the

offered pottery should have included vases of later date, as for

example stamped ware or hints of ornate style, or some white-

ground lekythoi of the very end of the century, like those of the

Group R and Huge or polychrome lekythoi.

121

K. Kiibler, Kerameikos Vll.1: Die Nekropole der Mitte des 6.

his Ende des 5. Jahrhunderts (Berlin 1976), 199; Houby Nielsen,

op.cit. n. 7, 146; I. Morris, Burial and Ancient Society (Cambridge

1987), 100.

122

Some views on the cemeteries of Athens can be reconsidered:

in the known cemetery by Syntagma Square, the majority of the

grave offerings are dated in the last quarter of the 5th and in the

4th centuries. The cemetery seems to have started in the last

quarter of the 5th, probably because of the events of the plague.

The suggestion is that during the war new cemeteries appeared in

Athens.

Some philologists have suggested that Thucydides

exaggerates the events of the plague, since there is no

other testimony from ancient sources for that event. I

hope that eventually more common burials will be

discovered, for the benefit of the historian's reliabil-

ity. Until then, the mass burial of the Station at

Kerameikos is filling this void. Once more, we face a

201

A mass burial from the cemetery of Kerameikos

case, on which the historical and archaeological evi-

dence is in agreement. Thus, from now on this burial

can be considered as one of the absolutely dated

finds of the second half of the 5th century, along with

the Korkyraians' grave, the Rheneian Purification,

the Thespian Polyandrion and the Lakedaimonians'

burial in the Kerameikos.

Effie Baziotopoulou-Valavani

Curator of Antiquities

3rd Ephorate of Prehistoric and

Classical Antiquities, Athens

1 Aiolou St.

GR- 105 55 Athens

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- Mazarakis Ainian A. - Alexandridou A. THDokumen26 halamanMazarakis Ainian A. - Alexandridou A. THTheseus KokkinosBelum ada peringkat

- La Rosa Minoan Baetyls: Between Funerary Rituals and EpiphaniesDokumen7 halamanLa Rosa Minoan Baetyls: Between Funerary Rituals and EpiphaniesManos LambrakisBelum ada peringkat

- Burial Mounds and Ritual Tumuli of The GreeceDokumen14 halamanBurial Mounds and Ritual Tumuli of The GreeceUmut DoğanBelum ada peringkat

- End of Early Bronze AgeDokumen29 halamanEnd of Early Bronze AgeitsnotconfidentialsBelum ada peringkat

- Atika 4-12 Vek 16292781 PDFDokumen450 halamanAtika 4-12 Vek 16292781 PDFaudubelaiaBelum ada peringkat

- Vassileva Paphlagonia BAR2432Dokumen12 halamanVassileva Paphlagonia BAR2432Maria Pap.Andr.Ant.Belum ada peringkat

- Aubet, María Eugenia - The Phoenicians and The West - Politics, Colonies and Trade (1993, Cambridge University Press) - GIRATODokumen182 halamanAubet, María Eugenia - The Phoenicians and The West - Politics, Colonies and Trade (1993, Cambridge University Press) - GIRATODaria SesinaBelum ada peringkat

- Divine Interiors PDFDokumen268 halamanDivine Interiors PDFFatihUyakBelum ada peringkat

- Bernard - The Greek Kingdoms of Central AsiaDokumen31 halamanBernard - The Greek Kingdoms of Central AsiaJose Antonio Monje100% (1)

- Spyros E. Iakovidis - The Mycenaean Acropolis of Athens - 2006Dokumen308 halamanSpyros E. Iakovidis - The Mycenaean Acropolis of Athens - 2006vadimkoponevmail.ruBelum ada peringkat

- Scythian Kurgan of FilipovkaDokumen15 halamanScythian Kurgan of FilipovkaSzkitaHun77Belum ada peringkat

- Who Are The Greeks From Pontos?Dokumen8 halamanWho Are The Greeks From Pontos?xnikos13Belum ada peringkat

- Hiller - Mycenaeans in Black SeaDokumen15 halamanHiller - Mycenaeans in Black SeaFrancesco BiancuBelum ada peringkat

- Chios. Prehistoric SettlementDokumen539 halamanChios. Prehistoric SettlementivansuvBelum ada peringkat

- For The Temples For The Burial Chambers.Dokumen46 halamanFor The Temples For The Burial Chambers.Antonio J. MoralesBelum ada peringkat

- Balkan Pit Sanctuaries Retheorizing TheDokumen317 halamanBalkan Pit Sanctuaries Retheorizing TheVolkan KaytmazBelum ada peringkat

- Haggis Lakkos 2012Dokumen44 halamanHaggis Lakkos 2012Alexandros KastanakisBelum ada peringkat

- The Headhunting and BodyDokumen274 halamanThe Headhunting and BodydinaBelum ada peringkat

- The Stela of Usersatet and HekaemsasenDokumen26 halamanThe Stela of Usersatet and HekaemsasenAsmaa MahdyBelum ada peringkat

- vasecatalogMA PDFDokumen100 halamanvasecatalogMA PDFDodoBelum ada peringkat

- G.Tsetskhladze-SECONDARY COLONISATION-Italy PDFDokumen27 halamanG.Tsetskhladze-SECONDARY COLONISATION-Italy PDFMaria Pap.Andr.Ant.Belum ada peringkat

- Cyprus Antiquities 1876-89Dokumen126 halamanCyprus Antiquities 1876-89robinhoodlumBelum ada peringkat

- The Cities and Cemeteries of Etruria v2Dokumen600 halamanThe Cities and Cemeteries of Etruria v2Faris MarukicBelum ada peringkat

- Cult in Context - The Ritual Significance of Miniature Pottery in Ancient Greek Sanctuaries From The Archaic To The Hellenistic PeriodDokumen346 halamanCult in Context - The Ritual Significance of Miniature Pottery in Ancient Greek Sanctuaries From The Archaic To The Hellenistic PeriodAlmasy100% (1)

- Chrysoula Saatsoglou-Paliadeli - Queenly - Appearances - at - Vergina-Aegae PDFDokumen18 halamanChrysoula Saatsoglou-Paliadeli - Queenly - Appearances - at - Vergina-Aegae PDFhioniamBelum ada peringkat

- Alberti 2009 Archaeologies of CultDokumen31 halamanAlberti 2009 Archaeologies of CultGeorgiosXasiotisBelum ada peringkat

- Corpus Vasorum Antiquorum - Fascicule 1 PDFDokumen176 halamanCorpus Vasorum Antiquorum - Fascicule 1 PDFJose manuelBelum ada peringkat

- Mycenaean Burial CustomsDokumen8 halamanMycenaean Burial CustomsVivienne Gae CallenderBelum ada peringkat

- D. H. French - Late Chalcolithic Pottery.....Dokumen44 halamanD. H. French - Late Chalcolithic Pottery.....ivansuvBelum ada peringkat

- ATHENA HADJI and ZOË KONTES: The Athenian Coinage DecreeDokumen5 halamanATHENA HADJI and ZOË KONTES: The Athenian Coinage Decreefeltor21Belum ada peringkat

- Neolithic Beginnings Between Northwest Anatolia and the Carpathian BasinDokumen231 halamanNeolithic Beginnings Between Northwest Anatolia and the Carpathian BasinPaolo BiagiBelum ada peringkat

- Athenian Agora Vol 22 (1982) - Hellenistic Pottery Moldmade Bowls PDFDokumen250 halamanAthenian Agora Vol 22 (1982) - Hellenistic Pottery Moldmade Bowls PDFIrimia AdrianBelum ada peringkat

- (Reynold A. Higgins) Minoan and Mycenaean Art (B-Ok - CC) PDFDokumen109 halaman(Reynold A. Higgins) Minoan and Mycenaean Art (B-Ok - CC) PDFMarija Labady-ĆukBelum ada peringkat

- 3annales Du Service Des AntiquitesDokumen512 halaman3annales Du Service Des Antiquitessendjem20100% (2)

- Varrones Murenae Ver3 - 2 PDFDokumen33 halamanVarrones Murenae Ver3 - 2 PDFJosé Luis Fernández BlancoBelum ada peringkat

- Excavations at Al MinaDokumen51 halamanExcavations at Al Minataxideutis100% (1)

- Makron Skyphos Drinking CupJSEDokumen36 halamanMakron Skyphos Drinking CupJSEsudsnzBelum ada peringkat

- Dating The Earliest Coins of Athens, Corinth and Aegina / John H. Kroll and Nancy M. WaggonerDokumen18 halamanDating The Earliest Coins of Athens, Corinth and Aegina / John H. Kroll and Nancy M. WaggonerDigital Library Numis (DLN)Belum ada peringkat

- The Artifacts of Chiapa de Corzo, Chiapas, MexicoDokumen113 halamanThe Artifacts of Chiapa de Corzo, Chiapas, MexicoRebecca DeebBelum ada peringkat

- Iron AgeDokumen36 halamanIron Agealousmoove20100% (1)

- Hendrickx JEA 82Dokumen22 halamanHendrickx JEA 82Angelo_ColonnaBelum ada peringkat

- Roller, Duane W. - The Building Program of Herod The GreatDokumen177 halamanRoller, Duane W. - The Building Program of Herod The GreatEditorial100% (1)

- Journal of Cuneiform Studies-Vol. 58-2006 PDFDokumen143 halamanJournal of Cuneiform Studies-Vol. 58-2006 PDFeduardo alejandro arrieta disalvoBelum ada peringkat

- Dietrich PDFDokumen18 halamanDietrich PDFc_samuel_johnstonBelum ada peringkat

- Tomlison Perachora: The Remains Outside The Two Sanctuaries 1969 PDFDokumen129 halamanTomlison Perachora: The Remains Outside The Two Sanctuaries 1969 PDFAnonymousBelum ada peringkat

- 3journal of Egyptian ArchaeologyDokumen350 halaman3journal of Egyptian Archaeologyالسيد بدرانBelum ada peringkat

- 8 - Chatby & Mostapha Kamel TombsDokumen17 halaman8 - Chatby & Mostapha Kamel TombsAbeer AdnanBelum ada peringkat

- 1457 - v2 Gold Jewellery in Ptolemaic, Roman and Byzantine EgyptDokumen281 halaman1457 - v2 Gold Jewellery in Ptolemaic, Roman and Byzantine Egyptjsmithy456Belum ada peringkat

- Hirbemerdon Tepe Final Report Chronicles 3 MillenniaDokumen595 halamanHirbemerdon Tepe Final Report Chronicles 3 MillenniaJavier Martinez EspuñaBelum ada peringkat

- Verre IsingsDokumen22 halamanVerre Isingsbouleux100% (2)

- Arch of TitusDokumen2 halamanArch of TitusMahanna Abiz Sta AnaBelum ada peringkat

- Attalid Asia Minor: Money, International Relations and the StateDokumen358 halamanAttalid Asia Minor: Money, International Relations and the StateJosé Luis Aledo MartinezBelum ada peringkat

- Networks of Rhodians in Karia PDFDokumen21 halamanNetworks of Rhodians in Karia PDFMariaFrankBelum ada peringkat

- 13th International Colloquium on Roman Provincial Art AbstractsDokumen35 halaman13th International Colloquium on Roman Provincial Art AbstractsLóstregos de Brest100% (1)

- Alfred Kidder - Excavactions at Kaminal Juyu 1945 PDFDokumen18 halamanAlfred Kidder - Excavactions at Kaminal Juyu 1945 PDFJose AldanaBelum ada peringkat

- British Museum Graeco-Roman SculpturesDokumen120 halamanBritish Museum Graeco-Roman SculpturesEduardo CastellanosBelum ada peringkat

- Woodcutters, Potters and Doorkeepers Service Personnel of The Deir El Medina WorkmenDokumen35 halamanWoodcutters, Potters and Doorkeepers Service Personnel of The Deir El Medina WorkmenZulema Barahona MendietaBelum ada peringkat

- Women in Ancient Egypt: Revisiting Power, Agency, and AutonomyDari EverandWomen in Ancient Egypt: Revisiting Power, Agency, and AutonomyBelum ada peringkat

- Greek Archaeology on the Black Sea CoastDokumen19 halamanGreek Archaeology on the Black Sea CoastpharetimaBelum ada peringkat

- Thesprotia Dodoni 5 (1976), P. 273 F. PREND!, CAH 2 III 1, P. 220 P. MOUNTJOY, Mycenaean Decorated Poltery: A Guide To IdentificationDokumen13 halamanThesprotia Dodoni 5 (1976), P. 273 F. PREND!, CAH 2 III 1, P. 220 P. MOUNTJOY, Mycenaean Decorated Poltery: A Guide To Identificationtesting124100% (1)

- Axenov S., The Balochi Language of Turkmenistan. A Corpus-Based Grammatical DescriptionDokumen336 halamanAxenov S., The Balochi Language of Turkmenistan. A Corpus-Based Grammatical DescriptionLudwigRossBelum ada peringkat

- CAERE (Modern Cerveteri) - The First of The Major Etruscan Cities To Expand To Mediterranean-Wide Contact, Sea Power, and Trading WealthDokumen58 halamanCAERE (Modern Cerveteri) - The First of The Major Etruscan Cities To Expand To Mediterranean-Wide Contact, Sea Power, and Trading WealthLudwigRossBelum ada peringkat

- A Post-Byzantine Mansion in AthensDokumen10 halamanA Post-Byzantine Mansion in AthensLudwigRossBelum ada peringkat

- Ancient Egyptian Baths Heated Like Their Greek CounterpartsDokumen28 halamanAncient Egyptian Baths Heated Like Their Greek CounterpartsLudwigRossBelum ada peringkat

- The Minoan Tsunami, Part I: Film Review: 300Dokumen24 halamanThe Minoan Tsunami, Part I: Film Review: 300LudwigRossBelum ada peringkat

- Dance in Bronze Age GreeceDokumen20 halamanDance in Bronze Age GreeceLudwigRossBelum ada peringkat

- Ancient Euthanasia: Good Death' and The Doctor in The Graeco-Roman WorldDokumen11 halamanAncient Euthanasia: Good Death' and The Doctor in The Graeco-Roman WorldLudwigRossBelum ada peringkat

- CSAPO MILLER The Origins of Theater in Ancient Greece and Beyond. From Ritual To DramaDokumen10 halamanCSAPO MILLER The Origins of Theater in Ancient Greece and Beyond. From Ritual To DramaLudwigRoss100% (1)