DeSoto's Misdiagnosis

Diunggah oleh

mohawk1680Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

DeSoto's Misdiagnosis

Diunggah oleh

mohawk1680Hak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Mystifying the Concept of Capital

Hernando de Sotos Misdiagnosis of the Hindrance to Economic Development in the Third World

J AMES C. W. A HIAKPOR

nhis well-publicized book The My s t e ry o f C a pi t a l (2000), Hernando de Soto claims to have discovered the explanation for poverty in countries of the Third World and the former Soviet Communist bloc. He claims it is the inability of the

poor p eop le in these c ountr i es to conver t the ir d ead ca pita l i nto l ive, functioning capital because of a legal apartheid their governments have created. He asserts

tha t the c onver s i on of d ea d c a p ita l i nto li ve c ap i ta l e xp la i ns the r is e of c a pi ta l is m , which he eq ua tes wi th economic d evelopme nt, i n the West. N umer ous re viewe rs of the book have praised de Sotos diagnosis of the cause of underdevelopment and his recom mend ation of the wid e spread g ranti ng of form al ti tles to pr ope rties ow ned b y the poor a s a s ol uti on to this p r obl e m . I n ac ad e m ic j ourna l s , the p os i ti ve re vi ew s i nc l ud e thos e by Lib ec a p (2001) , Buc h (2002) , R ose nb er g (2002) , a nd Pa l (2003) . I n the p r oc e s s of d e ve l op i n g hi s a r g um e nt , d e S o to r e f e r s to the w e l l -k now n explanation that clearly defined and enforceable property rights reduce transactions costs (Coase 1937) and promote investments, thus earning Ronald Coases endorsement of the book: A very great book. . . powerful and completely convincing. It will

James C. W. Ahiakpor is a professor of economics at California State University, East Bay.

The Independent Review, v. XIII, n. 1, Summer 2008, ISSN 10861 653, Copyright 2008, pp. 5779.

57

58

JAME S C. W. AHIAKPOR

have a most salutary effect on the views held on economic development. Similarly, Milton Friedman endorsed the book, noting: De Soto has demonstrated in practice that titling hitherto untitled assets is an extremely effective way to promote economic development of society as a whole. He offers politicians a project which can contribute to the w e lfa r e of the i r c ountr y a nd a t the sa m e ti me e nha nc e the i r ow n p ol i tic al standing, a wonderful combination (see the book s back dust cover for both quotations). 1 Comparing de Soto s claims with some of the grand development theories of the 1950s and 1960s, Ja gdish Bhagwati (C ol umbi a U niversi ty) als o d ecla res tha t

d e S ot o i s a r g ua b l y the m os t i nte r e s ti ng i nte l l e c t ua l w r i ti ng on d e v e l op m e nt to day. . . . [He] is the man with big ideas. . . . His Mystery of Capital will endure as a work of extraordinary importance (qtd. in Clift 2003, 10). Th e E c o n o m i s t hails the book as the most intelligent . . . yet written about the current challenge of establ i s hi ng c a p i ta l i s m i n th e d e v e l op i ng w or l d ( C l i ft 2 0 0 3 , 8 ) . Despite these accolades, de Soto is quite mistaken in his diagnosis of the real h i nd r a nc e t o e c o n om i c d e v e l op m e n t i n t he T hi r d Wo r ld a nd f or m e r S o v i e t b l oc countries. Rather than the lack of titles to property, the problem is the inadequacy of their domestic savings to f i nance investment. Poor people in these countries hardly own assets, the absence of whose formal titles impairs their ability to borrow funds, or

cap ita l, for investment. T hus, de Soto s sugg ested s oluti on of a massi ve titli ng

program by the governments of these countries would be a wasteful diversion from what needs to be done in them to promote their economic prosperity. This point is implicit in Culpepper s criticism of de Soto s property-titling project as f l awed and

inherently biased against the landless and property-less tenants, although his book p ur p or ts to sp e ak on b e ha l f of, a nd to e mp ow e r, the p oor a nd d is e nfra nchi s ed

(2002 ). Be c a us e de S oto s b ook has r e c ei ve d num e r ous e nd ors em e nts fr om hi ghpro f i le f i gures, the fundamental errors of its premise need wide publicity in order to spare T hir d World governme nts from be ing m isl ed. 2

1. Among other high-pro f i le endorsers of de Soto s book are Margaret Thatcher, Javier Perez de Cuellar, Francis Fukuyama, and William F. Buckley Jr. Mrs. Thatcher argues that The Mystery of Capital has the potential to create a new, enormously bene f i cial revolution, for it addresses the single greatest source of failure in the Third World and ex-communist countries the lack of the rule of law that upholds private property and provides a framework for enterprise. It should be compulsory reading for all those in charge of the wealth of nations. De Cuellar thinks the book makes [a] crucial contribution. A new proposal for change that is valid for the whole world. Fukuyama observes that The Mystery of Capital constitutes one of the few and genuinely promising approaches to overcoming poverty to come along in a very long time, and Buckley argues that de Soto s book changes our understanding of where capital comes from. The consequences could be world-shattering. (All of these quotes are from the book s back or inside dust cover.) Believing de Soto s claims regarding the absence of the rule of law and private-property rights for the poor in the Third World, Sowell also concludes his review of the book by arguing: This book should be required reading for those including law professors who seem to think that property rights are just privileges for the rich. The poor need them most of all, especially if they want to stop being poor (2000). Former president Bill Clinton is also reported to have declared de Soto the world s greatest living economist ( Hernando de Soto 2007) because of the book. 2. Since the publication of The Mystery of Capital, de Soto has received numerous awards (nineteen between 2002 and May 2007), mainly from free-market adherents, including the Adam Smith Award (2002), the Milton Friedman Prize (2004), and the 2006 Innovation Award (Social and Economic Innovation) from The Economist magazine. It is unclear how much the selection of him for these awards was infl uenced by

TH E IN D E P E N D E N T RE V I E W

MY S T I F Y I N G T H E CO N C E P T O F CA P I T A L

59

De Soto appears to have arrived at his fundamental misdiagnosis of the hindrance to economic development primarily from his misconception of capital and the source from which it derives. He thinks that an implicit process buried in the intricacies of [the] formal property systems . . . creates capital in the West and that the formal property system is capitals hydroelectric plant . . . the place where capital is born (2000, 46, 47; hereafter cited by page number only). But this view is incorrect. Rather, it is a communitys savings that mainly create the capital that may be borrowed by titled or untitled property owners. De Soto compounds his misconception with a confusion between stocks of wealth and the relevant flows of savings, or capital, to finance investment. He also exaggerates the limited role of titles to property in the economic-development process of the more developed countries and misrepresents the historical causality between economic development and the titling of private property. His misdiagnosis of the principal impediment to economic development also appears to have been driven by his misperceptions of conditions in poor countries, misperceptions that he himself affirms with self-contradictory claims in the book, especially his view that most people there do not have property rights. Samuelson (2001), Woodruff (2001), Gilbert (2002), and Miranda (2002) have offered criticisms and warnings about the illusions of de Sotos proposal. Woodruff notes that the amount of capital that may be unlocked from the poors assets might be only a small percentage of that suggested by de Soto (2001, 1221). He also reports from a study of rural Thailand that owners of untitled land are as likely to receive credit as are farmers with titled land, even from banks, and that titles have little effect on credit obtained from non-bank sources such as traders (1219). Samuelson faults de Soto for his neglect of the cultural dimension of the pursuit of economic development, adding: Property rights are not the be all and end all of progress but a simple reflection of the larger culture. . . . [De Sotos] story of property rights is only an interesting sideshow (2001, 211). Gilbert reports that the granting of titles in Bogota, Colombia, has made little difference in peoples access to credit, and Miranda notes that after six years work and more than 1 million registered land titles [in Peru], a very small percentage of the people in the target population have credit, which in most cases is from the Banco de Materiales, a government credit system that provides credit to those with s e c u r e i n c o m e s and which is not based on those who have formal titles (2002, 263, emphasis added). Mirandas report answers Thomass query about the outcome of the land-titling project to which de Soto was

the acclaim he received for his earlier book The Other Path (1989), arguing the benefits of private enterprise and pointing out the burdens of government bureaucracy, or by his having founded the Institute for Liberty and Development in Lima, Peru. Several governments in the Third World have invited de Soto to advise them on the implementation of his projectthat is, to help them to find the key to unlocking the hidden wealth that already exists in their countries. He expected in 2003 to be working with twenty-five of these governments over the next two years (Clift 2003, 10). 3. De Soto appears to dismiss the relevance of the cultural dimension for explaining differences in the level of economic development, arguing that one day these cultural arguments will peel away as the hard evidence of the effects of good political institutions and property law sink in (225).

3

V OLUME X I I I , N UMBER 1 , S UMMER 2 0 0 8

60

JAME S C. W. AHIAKPOR

appointed by President Alberto Fujimori of Peru in the 1990s, but of which de Soto says nothing in the book to explain why this programme failed to generate credit for those who were registered (2002, 191). A recent study of a poor suburb of Buenos Aires, Argentina, by Galiani and Schargrodsky also finds only . . . modest effects on access to credit markets as a result of [property] entitlement (2005, 3). The land had been bought by the Argentine government and distributed to squatters. However, the preceding criticisms do not focus on de Sotos misconception of capital and of its sourcenamely, savingsor consider that titles may only increase the demand for loanable savings in the formal credit market without necessarily increasing the total supply.

4

Meanwhile, such notable textbook commentators as

Perkins, Radelet, and Lindauer (2006, 85, 414) and Gwartney and colleagues (2006, 38) repeat without criticism de Sotos claims that the absence of formal titles to property is a hindrance to economic development. I here follow up Woodruffs suggestion that policy makers . . . be alerted to the limitations of de Sotos proposals (2001, 1223). I also clarify Adam Smiths concept of capital, which de Soto misrepresents.

5

De Soto is reported to have admitted the insufficiency of his titling project to promote economic development, but insists on its primacy: Im not saying that other reforms arent necessary. Im simply saying that a property rights system is a principal reform, without which other reforms are difficult to manage. Its quite clear that property law alone does not resolve the other problems. But to me, what is also quite clear is that without property law, you will never be able to accomplish other reforms in a sustainable manner (Hernando de Soto 2007). In view of this insistence, his mistaken diagnosis requires correction, particularly for his free-market admirers who have been touting his program.

Mystifying Capital and Its Source

When a businessperson says he is looking for some capital to invest or set up an enterprise, he has in mind a sum of money (funds), typically to be borrowed at interest. Some of the funds may be used to purchase or rent machinery or equipment, rent space for the enterprise, purchase raw materials, and pay for the services of

4. In an attempt to defend de Sotos argument, a referee for this article gave the analogy of a rickshaw driver who might become financially independent by pledging his land, if he had title to it, as collateral for a loan to purchase the rickshaw instead of renting the vehicle. But how likely is it that a man so poor as to be only a driver of a rented rickshaw will also own land? The poor in the Third W orld typically are not property owners. 5. My article is not so much about the effects of land titling on landowners access to credit as it is about de Sotos misdiagnosis of the principal hindrance to economic development in the Third World and the irrelevance of his suggested remedy. Therefore, I focus on the relevant development literature; readers interested in the literature on land titling and access to credit may see Van Tassel 2004 and Jacoby and Minten 2007. I thank an anonymous referee for bringing these recent publications to my attention. However, these authors do not discuss de Sotos diagnosis of the hindrance to economic development.

TH E IN D E P E N D E N T RE V I E W

MY S T I F Y I N G T H E CO N C E P T O F CA P I T A L

61

workers. Some of the funds will also be kept on hand to pay incidental costs that the enterprise incurs or to provide change to customers before revenues start to flow in. Thus, borrowed capital is a larger sum of money than the value of the physical assets an entrepreneur purchases, which modern economists call capital goods machinery, e q u i pm e nt , r a w m at er i a l s , o r pr od uc e d g o ods y et t o b e s ol d. I t g o es wi t h o ut saying that income earners first must save if businesspersons are to borrow capital. Thus, capital is intimately connected with savings and interest rates. The greater the demand for capital relative to its supply (savings), the higher the rate of interest, and vice versa. This meaning of the term c a p i ta l is the one that the classical economists and several early neoclassical economists employed; see, for example, Adam Smiths

Wealth of Nations ([1776] 1976, 1:294301); David Ricardos Works and Correspondence (1951, 1:363, 2:331, 3:8994); J. S. Mills Collected Works (196388, 2:chap.

6, 3:chap. 23); Alfred Marshalls Principles of Economics ([1920] 1990, 6069); A. C. Pigous Industrial Fluctuations (1927, 12022, 13134); Frank Knights essay Professor Hayek and the Theory of Investment (1935) and book The Economic Orga-

nization ([1933] 1967, 11317); and J. B. Clarks The Distribution of Wealth (1938,

11656). Marshall argues that economists have no choice but to follow wellestablished customs as regards the use of the term capital in ordinary business, i.e. trade capital. In his reaction to Bhm-Bawerks ([1890] 1970) confinement of the term c a p i t a l to only capital goods and thus his failure to interpret correctly the classical capital supply-and-demand theory of interest, he urges economists to use t he l ang ua ge of t he mar k et - pl ac e ( [ 1920] 1 99 0, 64 7, 60) . Howe ver , f ol l owi n g J. M. Keynes ([1936] 1976), most modern economists tend not to heed Marshalls advice and attach only the meaning capital goods to the term c apital, qualifying the term with f in a nc ia l to refer to its original meaning. In contrast, Austrian economists who adopt the Bhm-Bawerkian analysis of capital and interest and meet with criticism from neoclassical writers would rather the term c a pi t al were banished from economics. Hayek points out, The .. . ambiguity of the term capital has been the source of unending confusion, and the suggestion has often been made [for example, by Schumpeter] . . . that the term should be banned entirely from scientific usages (1941, 9); I elaborate on this point in another article (Ahiakpor 1997). In The Mystery of Capital , de Soto extends the modern confusion over the term

c ap ital by suggesting that capital has an invisible existence, like television or radio

waves that are known to exist but cannot be seen or touched, and is congealed in the residential houses and lands that the poor occupy, although he qualifies this capital as being dead (7). Thus, instead of recognizing the paucity of savings or loanable capitalthat is, unconsumed income devoted to earning interest or profits (dividends), represented in financial assets such as bank deposits, mutual-fund shares, stocks, and bondsas the principal hindrance to economic development in the Third World, de Soto insists that the poorest sectors of society have saved. The quantity is enormous (11).

V OLUME X I I I , N UMBER 1 , S UMMER 2 0 0 8

62

JAME S C. W. AHIAKPOR

In de Soto s view, the problem for the Third World is a failure to recognize or understand how to convert their savings into capital (12): This is the mystery of capital. Solving it requires an understanding of why Westerners, by representing assets w i th ti tle s , a r e a b le to se e a nd d r aw out c ap i ta l fr om the m . One of the g re a tes t challenges to the human mind is to comprehend and to gain access to those things we know exist but cannot see (7). He believes that at least 80 percent of the population in these countries cannot inject life into their assets and make them generate capital because the law keeps them out of the formal property system. They have trillions of dollars in dead capital, but it is as if these were isolated ponds whose waters disappear into a sterile strip of sand, instead of forming a mighty mass of water that can be c a p tur ed i n one uni f i e d prop e r ty s ys tem a nd g i ve n the form re q uir e d to p r od uce capital (210). De Soto s conception of capital as being embedded in the dwelling places of the poor in the Third World leads him to urge the governments of these countries to turn inward to f i nd capital for economic development, not by changing policies that have inhibited their citizens saving, but merely by providing the poor with titles to their prope rties. Ins tead of wanderi ng the world s forei gn ministries and inte rna ti ona l

f i nancial institutions seeking their fortune, he argues, the leaders of these nations

should recognize that in the midst of their own poorest neighborhoods and shantytowns, there are if not acres of diamonds trillions of dollars, all ready to be put to use if only the m ystery of how ass ets are tr ans for med i nto li ve cap i tal can b e unraveled (37). De Soto s urging of these governments to rely on domestic sources for investment funds is well advised, 6 but the amount that he suggests can be retrieved (if one may grant legitimacy to his vision) merely by providing titles to the poor who by de f i nition do not own much is quite misleading. 7 He appears to mistake the possibility of pledging a clearly titled property as collateral for loans for the probability of obtaining such loans. But without adequate savings, the poor still would have little c ha nc e o f ob ta i ni ng t he c a p i t a l th a t w o ul d b e r a t i on e d a t h i g he r i n t e r e s t r a t e s and obtainable by those with better-quality assets than those of the poor.8 As

6. Numerous analysts (e.g., Bauer 1981; Easterly 2003) have noted that it is futile for less-developed countries to expect to secure their economic prosperity primarily from reliance on foreign aid, instead of from the creation of conditions to promote domestic savings and investment. Thus, de Soto here strikes a familiar chord with analysts inclined toward free- market, self- reliant policies as well as with those who simply have been disappointed with the poor record of foreign aid in the less- developed countries. 7. Woodruff notes that de Soto s estimates are highly in f l ated: Given inevitable slippage in translating collateral into loans, the capital unlocked from these assets might be only a small percentage of that suggested by de Soto (2001, 1221 ). M iranda (2002) also notes the exaggeration in de Soto s estimates. But note that the values of collaterals themselves do not generate capital; loanable savings do. 8. At best, one may argue that the newly quali f i ed (property-titled) borrowers might face a lower rate of interest than they did in the informal capital or credit market, and the rate of interest on the informal market might fall because of a reduced demand for loans there. But there is little reason to expect the total amount of loans made on both the formal and informal credit markets to rise simply from the shuf f l ing of borrowers fro m on e m ark et to anot he r.

TH E IN D E P E N D E N T RE V I E W

MY S T I F Y I N G T H E CO N C E P T O F CA P I T A L

63

David Ricardo well makes the point, credit does not create Capital, it determines only by whom that Capital should be employed (1951, 5:43637). Besides, lending to small-scale businesses in poor countries relies precious little on the ownership of titles to property (see, for example, Perkins, Radelet, and Lindauer 2006, 5068). Indeed, lenders are more interested in the likelihood of a borrowers repayment on account of the probable success of the enterprise for which the loans are extended than in the possibility of collecting payment from the sale of pledged assets. Maintenance and selling costs are involved in attempting to recover the loan principal from pledged assets (not to mention the interest that may be forgone). Lenders are also eager to receive their expected repayments of loans in order to meet their own short-term obligations. Furthermore, there hardly are primary, let alone secondary, markets for shacks the poor may build on rural parcels of land in most Third World countries to make property foreclosure sales feasible, be they in Haiti, Egypt, Peru, or the Philippines, the countries de Soto and his group have visited. It also may be against the cultural norms for a lender to sell the dwelling places of borrowers in default, even where the law permits such sales.

9

De Soto attributes to Adam Smith the view that capital is not the accumulated stock of assets but the p o t e n t i a l it holds to deploy new production (42, emphasis in original). He also attributes to Smith, Sismonde de Sismondi, and Karl Marx the view that capital is first an abstract concept and must be given a fixed, tangible form to be useful (4243). But de Sotos pursuit of the abstract notion of capital leads him away from a recognition that Smith clearly defines capital first as funds and derives its origin from savings before the borrowed capital takes the forms of fixed and circulating capital in the hands of producers: Capitals are increased by parsimony and diminished by prodigality and misconduct. Whatever a person s a v e s from his revenue he adds to his c a p i t a l , and either employs it himself in maintaining an additional number of productive hands, or enables some other person to do so, by lending it to him for an interest, that is, for a share of the profits. As the capital of an individual can be increased only by what he saves from his annual revenues or his annual gains, so the cap ita l o f so ciety, which is the same with that of all the individuals who compose it, can be increased only in the same manner. ([1776] 1976, 1:35859, emphasis added)

9. In some Third W orld countries, the law prohibits lenders from selling the land or the houses of borrowers who are in default (see Van Tassel 2004). These restrictions are supposed to protect the poor from lenders, although their operation may appear to affirm de Sotos claim of a legal apartheid against the poors access to credit. In 2007, even the U.S. government put pressure on banks and some other mortgage lenders not to foreclose on the properties of so-called subprime borrowers in default, but to work with them to keep their homes. Alston (1984) recounts legislation by U.S. states barring farm foreclosures in times of economic distress during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

V OLUME X I I I , N UMBER 1 , S UMMER 2 0 0 8

64

JAME S C. W. AHIAKPOR

W h e n S m i th d i s ti ng u i s he s c a p i ta l fr o m m o ne y , a p o i n t d e S o t o ( 4 3 ) n ot e s , he is only warning against mistaking the medium (money) through which capital (savings) may be conveyed from savers to borrowers for the substance of what is conveyed. Thus, an increase in the quantity of money specie or, in our time, p a pe r d oe s not m ea n tha t the r e a l p urc has i ng p ow e r of s a vi ngs r i se s or tha t the rate of interest at which savings are borrowed falls. For example, between 1988 and 1990, Peru s centr al ba nk i ncreas ed the quanti ty of currenc y at an a vera ge annua l rate of 3,263 percent, but the deposit interest rate averaged 1,246 percent and the rate of in f l ation averag ed 3,849 percent wi thout the economy s expe ri enci ng r ea l growth. Further mor e, S mi th tal ks ab out the conve rsion of dea d stock [ cap ital ] into a c ti ve a nd p r od uc tive s toc k thr oug h the jud ic i ous op e r a tions of b a nki ng w hen b a n k s k e e p n o m o r e o f t he c o m m u n i t y s s a v i n g s d e p o s i t e d w i t h t h e m t h a n t h e y need in ready money for answering occasional demands ([1776] 1976, 1:341, 340). This obser vation is offe red to exp la in frac tional rese rve ba nki ng s posi ti ve contribution to economic growth, not to designate dwelling places as custodians of

dead capital capable of being converted into active capital for production.

Thus, de Soto s employment of the term d e a d c a p i t a l may have been an ingenious b or r ow i ng from S mi th s l ang ua ge , but the c ontex t to whi c h d e S oto a pp l i es i t l ea ds to his fai lur e to rec ognize that i ncre ased loanab le sa vi ngs, not ti tl es to pr oper ti es ow ned b y the p oor , ar e the s ourc e of l i ve c a pi ta l to p r om ote g row th. I t is m is leading to claim that capital is the result of discovering and unleashing potential energy from the trillions of bricks that the poor have accumulated in their buildings (40).

Confusing Stocks and Flows

De S oto s vi e w tha t tr i l l i o n s of d ol l a r s w or th of d e a d c a p i ta l e x i s t i n the T hi r d Wor l d w a iti ng to b e tur ne d i nto p r od uc ti ve c a pi ta l , i f onl y the conve rs i on p r oc ess were initiated with the granting of legal titles to property, confuses the stock of wealth with the f l ow of capital, or savings, needed for investment. His estimates are based onl y on the p erce ived ma rke t va lues of the p oor s dwel li ngs. A t a ny p oi nt i n ti m e , the va l ue s of a s s e ts ow ne d b y the p oor m a y w e l l b e enormous, given that to determine this value one is simply estimating the value of the land and dwelling places they inhabit, although in per capita terms the values owned by the middle class and the rich may be signi f i cantly greater. However, it is the current or annual additions to stocks, or savings ( f l ows), that matter for the promotion of economic growth. Such f l ows provide the funds for hiring additional labor, acquiring tools and machinery to assist labor in production, and obtaining the raw materials to b e p r oc es s ed . Le vi ne (1997) p r ovi d es a n e xc e l l e nt emp i r ic a l d em onstr a ti on of thi s point, besi des summar izi ng other s tud ies tha t a ff i r m i t. Littl e of r ele va nce tur ns on

TH E IN D E P E N D E N T RE V I E W

MY S T I F Y I N G T H E CO N C E P T O F CA P I T A L

65

whether de Soto correctly estimates the dead capital in land values of Third World and former Communist bloc countries to be worth $9.3 trillion, or very nearly as much as the total value of all the companies listed on the main s t o c k e xc h a n g e s o f t h e w o r l d s t w e n t y m o s t d e v e l o p e d c o u n t r i e s : New York, Tokyo, London, Frankfurt, Toronto, Paris, Milan, the NASDAQ, and a dozen others. It is more than twenty times the total direct foreign investment into all Third World and former communist countries in the ten years after 1989, forty-six times as much as all the World Bank loans of the past three decades, and ninety-three time as much as all development assistance from all advanced countries to the Third World in the same period (35). The dead capitals themselves are of little use in production, but the funds (savings) used to purchase stocks traded on capital markets make increased production possible. The economic functions of the two types of assets must not be confused. The rural parcels of land have existed in these countries since their founding, and they cannot to be compared meaningfully with World Bank loans, development assistance, or foreign direct investment over any period of time. Indeed, with economic development made possible by increased savings, the value of other forms of wealth may exceed the value of land.

The Limited Role of Property Titles

De Soto gives the impression that it is primarily, if not only, titles to property that enable people to transform their dead capital into the live capital needed for production. But titles only make it easier for the grantor of a loan to seize the property represented by the title in case of default. They do not increase the available loanable funds, or capital. Given the rate of savings, an increase in the pool of borrowers may only cause lenders to pay closer attention to other discriminating aspects of borrowers. Among these aspects are the borrowers cash flows, constancy or regularity of employment, and previous repayment history. On these criteria, we can hardly expect the poor in the Third W orld to outperform the well-to-do who already borrow capital in their underdeveloped financial markets for investment. However, an increased flow of savings may lower interest rates as well as induce lenders to relax their qualifying criteria for potential borrowers. The case of mortgage lenders who extended loans without requiring the traditional 20 percent down payment or carefully verifying potential borrowers sources of income during the early 2000s in the United Statesthe so-called subprime lending phenomenonillustrates the point. In 2001, an 8 percent interest rate on a thirty-year mortgage loan was a good rate, but by 2005 the rate for a similar loan had dropped to 5.5 percent. Funds

V OLUME X I I I , N UMBER 1 , S UMMER 2 0 0 8

66

JAME S C. W. AHIAKPOR

clearly had moved out of stocks into mutual funds and certif i cates of deposit, signif i cantly depressing their interest rates. With a lower cost of funds, mortgage lenders too could afford to charge historically low rates to borrowers, even though credit worthiness still may have affected some individual loan rates. De Soto also draws the wrong inference from the history he recounts of squatting in the United States, particularly by the early settlers in Maryland, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Vermont, and Pennsylvania. Those who took possession of land as squatters f i rst acquired capital, or savings, which they used to build the cabins and till the land as required of them. Thus, under Massachusetts law, a settler s duties included taking actual possession and within three years, building a house of a certain size, usually eighteen or twenty feet square, and clearing f i ve to eight acres for mowing and tilling (115). In this way, squatters acquired their

cabin, tomahawk, or corn rights, subsequently to be recognized by state or

federal governments. Those squatters were people of considerable means who did everything they could to secure the [public] land they occupied; some even paid twice for the same parcel, while others paid lawyers enormous fees to help them make their land legal (135 36). Thus, the positive contemporaneous view of the early settlers that de Soto quotes from Senator Henry Clay hardly applies to the poor squatters of present-day Third World and former Communist countries: They [the early settlers] build houses, plant orchards, enclose fi elds, cultivate the earth, and rear up families around them. Meanwhile, the tide of emigration f l ows upon them, their improved farms rise in value, a demand for them takes place, they sell to the newcomers at a great advance, and proceed farther west. . . . In this way, thousands and tens of thousands are daily improving their circumstances and bettering their conditions (132). Moreover, Third World squ atters are not foreigners or immigrants occupying the lands of dispossessed natives; neither are they people with suf f i cient means to build appreciable houses, till lands of any signi f i cant size, and plant orchards. Rather, they are violators of their fellow citizens property rights. Respect for the law, which de Soto recognizes as a requirement for the successful building of capitalism, suggests rather that governments enforce the property owners rights against squatters by guaranteeing the interlopers eviction. As Adam Smith notes, Civil government, so far as it is instituted for the security of property, is in reality instituted for the defence of the rich against the poor, or of those who have some property against those who have none at all ([1776] 1976, 2:236). Till there be property, he points out, there can be no government, the very end of which is to secure wealth and to defend the rich from the poor (from L ec t ur es , qtd. in Smith [1776] 1976, 2:236n).1 0

10. John Locke s version of the same point is that government has no other end but the preservation of property (qtd. in Smith [1776] 1976, 2:236n).

TH E IN D E P E N D E N T RE V I E W

MY S T I F Y I N G T H E CO N C E P T O F CA P I T A L

67

Other Problems with de Sotos Claims

Several of de Sotos claims are factually incorrect, and others are self-contradictory. About conditions in the Third World, he incorrectly states that nobody can identify who owns what. . . . [P]eople cannot be made to pay their debts. . . . [T]he rules that govern property vary from neighborhood to neighborhood or even from street to street (15); that peasants face an impenetrable wall of rules that bar . . . them from legally established social and economic activities. It [is] tremendously difficult for these new city people to acquire legal housing, enter formal business, or find a legal job (18, repeated on 82); that [e]xtralegal asset owners are . . . denied access to credit (84), and many statutes . . . wall off the majority of people from capital (188); and that the sale or lease of a house may involve lengthy and cumbersome procedures of approval involving all the neighbors (47). Among other assertions that easily can be shown to be incorrect are: Even as the West prospers from abundant capital, people really [do not] understand the origin of capital (8), and ironically, the enemies of capitalism have always seemed more aware of the virtual origin of capital than capitalists [are] themselves (222); Capital, the most essential component of Western economic advance, is the one that has received the least attention (1011); The genius of the West was to have created a system that allowed people to grasp with the mind values that human eyes could never see and to manipulate things that hands could never touch (63); Money does not earn money. You need a property right before you can make money (64); the classical economists [including Adam Smith], who knew capital was abstract and had to be fixed, [did] not make the connection between capital and property (65); and Capitalists generally have no systematic explanation of how the people in the underclass got where they are and how the system could be changed to raise them up (213). That capital originates in savings has been well known to economists for a long time, and the policies to encourage increased capital formation to promote economic growth have been urged since the time of Adam Smith. Even as modern Keynesian macroeconomics has taught the myth that increased saving causes a decline in aggregate demand, hence an economys declineas in the paradox of thrift proposition (see Ahiakpor 1995)growth theories, from the Harrod-Domar model

V OLUME X I I I , N UMBER 1 , S UMMER 2 0 0 8

68

JAME S C. W. AHIAKPOR

to the Solow model, have emphasized the importance of increased savings for prom oti ng e c onom i c g r ow th. (S e e a ls o G ol ds m i th 19 69; Mc Ki nnon 1973; Le vi ne 1997; and development economics texts such as Meier and Rauch 2005, esp. chap. 5, and P e r kins , R a de l e t, a nd Lind aue r 2006 , e sp . c ha ps . 10 a nd 13 .) Indeed, modern growth theories may be read as illustrating Smith s explanation that [t]he annual produce of the land and labour of any nation can be increased in its value by no other means, but by increasing either the number of its productive labourers, or the productive powers of those labourers who had been employed. The number of its productive labourers, it is evident, can never be much increased, but in consequence of an i nc r eas e of c a pital , or the fu n ds d e s t in e d f o r m a i n ta i ni n g t he m . The productive powers of the s a me num be r of l ab oure r s ca nnot be i nc re as e d , but i n c onse q uenc e either of s ome addi ti on a nd impr ove ment to thos e m achi nes a nd i nstr um e nts w hi c h fa c i l i ta te a nd a b r i d g e l a b our ; o r o f a m o r e p r op e r d i v i s i o n and distribution of employment. In either case an a d d i t i o n a l c a p i t a l is almos t alwa ys r equired . I t i s by mea ns of an add itional capi ta l onl y, tha t the undertaker of any work can either provide his workmen with better machinery, or make a more proper distribution of employment among them. . . . When we compare, therefore, the state of a nation at two different periods, and f i nd, that the annual produce of its land and labour is evidently greater at the latter than at the former, that its lands are better cultivated, its manufactures more numerous and more f l ourishing, and its trade more extensive, we may be assured that its capital must have increased duri ng the inte rva l betwe en those two per iods , and tha t mor e must have been a d d e d to it by the good conduct of some, than had been taken from it e ither by the pri va te m isc onduc t of some, or b y the p ubl ic ex tra vaga nce of g ove r nm e nt. ([1776] 1976 , 1 :365 , e mp has is ad de d)

Ricardo rei te rates Sm ith s p oint when he obs er ves tha t the wealth of a country may be increased in two ways: it may be increased by emp loyi ng a gr eater p ortion of revenue i n the m aintenanc e of pr oduc tive labour [i.e., increased savings], which will not only add to the quantity, but to the value of the mass of commodities; or it may be increased, without employing any additional quantity of labour by making the same q ua nti ty mor e pr od uc ti ve, w hic h w il l a dd to the a bund a nc e , but not to the value of commodities. In the f i rst case, a country would not only become rich, but the value of its riches would increase. It would become rich by p a r s i m o n y ; by diminishing its expenditure on objects of luxury and enjoyment; and employing those s a v i n g s in reproduction. (1951 , 1: 278, emphasis added)

TH E IN D E P E N D E N T RE V I E W

MY S T I F Y I N G T H E CO N C E P T O F CA P I T A L

69

Baumol reproduces, though in a different context, J-B. Say s (1803) restatement of the same classical emphasis on savings as a principal determinant of economic growth:

As for a nation that does not expend its entire income, and annually augments its capital, that is the one and the only one that provides the greatest annual markets for its product. In effect, each year it experiences growth in the pro f i ts from its capital and in the power of its industry and, consequently, in its income; that is to say, its means of consumption either direct or thr oug h e xc ha ng e , i n one w ord , i ts ma r kets . T he p ubl i c i nte re s t i s consequently not served by consumption, but it is served and served prodigiously by saving, and though it seems extraordinary to many persons, not being any the less true as a consequence, the labouring class is served by i t more tha n a nyone els e. (1977, 150)

De Soto s claim that most people [in the Third World] do not have property rights (211) a claim that appears to have signi f i cantly in f l uenced the positive evaluations of his book by Sowell (2000), Baetjer and Lineberry (2003), Gwartney and coll eag ues (2006), and Morris (2007) is a myth. T he right to pr ivate prope rty is widely recognized in most non-Communist Third World countries, even where people do not have any government-issued documents attesting their ownership (see, for ex ampl e, Besle y 1995). Thes e c ountr ies ha ve noti ons of the ft or violations of property rights, and in traditional or rural settings they have mechanisms for punishing or discouraging theft. Rental property owners in the urban areas of the Third World do not turn away prospective renters from the rural areas who show f i nancial ability to pay. The problem for migrants from the rural areas may instead be their inability to afford the higher rents in the urban areas. De Soto s notion of a legal apartheid separating people of rural and urban origins in their economic activities is also a myth. The prevalence of lending and borrowing in the informal market also vitiates his claim that non-holders of formal titles to property are denied access to credit in the Third World. It also reveals as incorrect his notion that money does not earn money for the non-formal title holder. De Soto s description of activities in the informal sector as extralegal, a term he s om e tim es e q uate s w i th i l le g a l i ty, i nc or r ec tl y ta r nis he s the l e gi ti m a te , we l fa re improving, economic activities undertaken in the informal sectors of Third World countries. Thus, he compares the so-called l a w a b i d i n g sector on one side [with] the impoverished extralegal sector (213, emphasis added) and argues that when people have access to an orderly mechanism to settle land that re f l ects the social contrac t, they wi ll ta ke the l e g a l r o u t e , and onl y a minori ty, li ke anywher e els e, will insist on extralegal appropriation (226, emphasis added). In the informal secV OLUME X I I I , N UMBER 1 , S UMMER 2 0 0 8

70

JAME S C. W. AHIAKPOR

tor of less-developed countries, production activities common in agriculture, services, and small manufacturing are for the most part not illegal activities. It is also well known tha t the i nform al sector s s ize dec lines on its own as econom ic grow th oc c ur s ( s e e , for e x a m p l e , M e i e r a nd R a uc h 20 05 ; P e rki ns , R a d e l e t, a nd Li nd a ue r 2006). I count a number of s el f-c ontrad ictory cla ims in d e Soto s work: He observes correctly that economic development occurred in the United States at the hands of immigrants, who settled boundaries, ploughed f i elds, built homes, transferred land, and established credit long before governments conferred on them a ny r i g h t t o e ng a g e i n t he s e a c ts ( 1 6 ) thr oug h t i tl e s . But he a l s o d w e l l s o n th e primacy of legal titles as a prerequisite for economic development in the Third World. He describes the vibrancy of the informal or extralegal sector, as in the Brazilian fav elas , where there are no rent controls . . . ; rents are paid in U.S. dollars, and renters who do not pay are rapidly evacuated (21), and characterizes this sector as a place where street-side cottage industries have sprung up . . . , manufacturing anyt h i ng f r om c l o t h i n g a n d f oo tw e a r t o i m i t a ti o n C a r ti e r w a tc he s a n d V u i tt o n B a g s . There are workshops that build and rebuild machinery, cars, even buses . . . entire indus tr ies a nd neig hbor hoods tha t ha ve to oper ate on cla ndes tine connec ti ons to elec tr ici ty a nd wate r. T her e are even de ntists who f i l l cavi ties w ithout a l ice nse (28). 1 1 Yet elsewhere he argues that without integration into the formal or legal sector through titles, these economies have little chance for growth or development. He asserts that property, like energy, is a concept; it cannot be experienced directly. . . . And no one can see property (49) even though it is properly surveyed, mapped, and recorded (154). Yet he also argues that a title to property enables one

to se e i t as li ve cap ital (50) or eve n to touch [the] c apital (63).

He declares that in the extralegal sector of the less-developed countries nobody real ly knows who owns what (32) and the p oor ha ve ple nty of thi ngs, but the i r property rights are not def i ned by any law (74). Yet he claims that in these same communities illegal tenancy contracts [are] declared before a notary ; that

[a]lthough their laws may be outside formal law, they are, by and large, the only laws with which these people are comfortable (88); that it is extralegal law that regulates the assets of most citizens (175); that asset owners in the extralegal sector are . . . relatively well organized [and] law-abiding, although the laws they abide by a r e no t t h e g o ve r n m e n t s ( 1 7 8 ) ; t ha t p e op l e i n th e u n d e r c a p i t a l i z e d s e c to r d o

11. In fact, besides obtaining a license to operate a commercial vehicle, private bus, jitney, or taxi, a driver does not need any of f i cial recognition of h i s r o u t e to operate in Third World countries, a recognition de Soto claims can take as many as twenty-six months of red tape to obtain (20). Routes are not drivers monopolies granted by government. Donald Stewart s vivid description of the Brazilian f a v e l a s as economie s born of th e ent rep re neu ri al spirit of pe asa nts a nd in wh ich the pro f i tab ili ty of i nvest me nt [i n housing] is good and as a result there is an abundance of supply of housing (1997, qtd. in de Soto 2000, 85) als o c ontr adict s de S oto s di m vi ew of the pr ospec ts f or ec on omic dev el opme nt w ith out a for m al integration of titles to property. An economy may be composed of formal and informal sectors, but the growth of the latter also improves the well- being of the economy s inhabitants.

TH E IN D E P E N D E N T RE V I E W

MY S T I F Y I N G T H E CO N C E P T O F CA P I T A L

71

have . . . strong, clear, and detailed understandings among themselves of who owns what (182); and that in Haiti he and his group did not find a single extralegal plot of land, shack, or building whose owner did not have at least one document to defend his righteven his squatting rights (183). He argues that massive extra-legality [in the Third World and former Communist countries] is not a new phenomenon. . . . When the Industrial Revolution began in Europe, governments were also plagued with uncontrollable migration, growth of the extralegal sector, urban poverty, and social unrest (93), and during the settlement of America, migrants began settling boundaries, plowing fields, building homes, transferring land, and establishing credit long before governments had conferred on them the right to do so (117). But he fails to see that the evolutionary process in economic developmentwhat he calls capitalismtook place in these countries without there first being a widespread government program of granting titles to property owned by the poor, and that such a program did not precede economic development in todays more-developed countries. He claims that in the Third World the rules that govern property vary from neighborhood to neighborhood or even from street to street (15). But elsewhere he declares that individual extralegal social contracts in the same country [are] more alike than different (180). At numerous places (for example, 30, 67, 82, and 159), he argues that the poor have been excluded from entering the formal sectors of Third World economies by some sort of legal apartheid or a bell jar. Yet he also notes that governments in developing countries have tried for 180 years to open up their property systems to the poor (154) and that programs to endow the poor with property exist in almost all developing and former communist countries (165). He observes correctly from the history of some of the more-developed countries that unconscious evolution rather than conscious planning created the integrated property systems in these countries (109) and that the extra-legals [in the less-developed countries] want to come in from the cold, as evidenced by the engaging and diplomatic leaders they select to negotiate on their behalf [who] hardly fit the stereotype of the street boss (17778). Yet in general he sees little prospect of economic development unless Third World governments engage in a massive, conscious, and planned integration of formal titles to property. Thus, de Sotos path to arriving at his conclusions about the dim prospects for economic development in the Third World and former Communist countries unless they implement his suggested granting of titles to property owned by the poor is littered with misperceptions, inaccuracies, and contradictions.

Further Evaluation and Conclusions

Before Adam Smith elaborated his blueprint for the process of efficient economic development in the W ea lt h of N at i o ns , he argued in 1755: Little else is requisite to

V OLUME X I I I , N UMBER 1 , S UMMER 2 0 0 8

72

JAME S C. W. AHIAKPOR

carry a state to the highest degree of opulence from the lowest barbarism but peace, easy taxes, and a tolerable administration of justice: all the rest being brought about by the na tural c ours e of things. Al l governme nts which thwar t this natura l course, which force things into another channel or which endeavour to arrest the progress of society at a particular point, are unnatural, and to support themselves are obliged to b e op p r e s s i ve a nd tyr a nni c a l ( q td . i n S m i t h [ 1 7 7 6] 1 99 6 , x l ) . S m i th s b l ue p r i n t includes government provision of security for its citizens against external and internal aggression, the administration of justice, and the erection of public works and institutions to facilitate the functioning of markets. De Soto s emphasis on the bene f i ts of clear titles to property and the state s enforcement of owners property rights may f i t unde r Sm ith s d uty of the sove reig n to admi nis te r jus tice , b ut the mass ive ti tli ng c a m p a i g n h e u r g e s o n t h e g o v e r n m e n t s o f T h i r d W or l d a n d f o r m e r C o m m u n i s t countries appears to obstruct the natural course of things in the process of eff i cient e c onom i c d eve l op m e nt. As de Soto himself recounts at numerous points, economic development in the indus tr ial ized countri es p rec eded the d eve lop me nt of ti tles to p ri va te p rop erty. Indeed, private companies now survive there by providing titling services to dealers in r e a l e s ta te . I n m any T hi rd Wor l d c ountr i es , g over nme nt off i ce s r eg i s te r ti tl es to property, although perhaps not as expeditiously as private title companies in the more d e ve l op e d c o un t r i e s ( s e e A tw o od 1 9 9 0 ; Be s l e y 1 9 9 5 ; J a c ob y a nd M i n te n 2 0 0 7 ). Private enterprise in titling services in the less-developed countries hardly exists primarily because the demand for such services is negligible. Their market for real estate, especially dwelling houses, is rather thin. Most people there save over long periods of time, typically during most of their adult working years, to build their own houses and then pass on the dwellings to their heirs. It is thus not uncommon in these countries for several of the builder s adult children to share rooms in the same building or to b ui l d a d d i t i ona l s t r uc tur e s on the s a m e fa m i l y c om p ound , w hi c h n one of the m would expose to foreclosure by pledging the property as collateral for a loan. Thus, de Soto s view of houses, including the shacks of the poor, as dead capital from which

live capital can be unlocked to f i nance investment projects in the Third World is

quite misleading. Some investors in the more-developed countries may well acquire funds through a second mortgage on their homes, as de Soto argues, but they are not among the p oor . Besid es, a sec ond mortgage is ti ed to the equity acc umula ted i n the home that is, the extent to which the indebtedness on the f i rst mortgage has been reduced, mainly through subsequent repayments (a form of savings accumulation) or through the market-value a ppreciation of the property (a form of return of the savings). Still, second mortgages are funded by the current f l ow of loanable savings, not by the quali f i cation to borrow represented by a property s legal title. T h e r e a s on w e s a v e , a s A d a m S m i t h n o te d , i s t h e d e s i r e o f b e t te r i n g ou r condi tion, a desi re which, thoug h ge ner al ly c alm and d ispassi ona te , comes wi th us from the womb, and never leaves us till we go into the grave ([1776] 1976, 1:362

TH E IN D E P E N D E N T RE V I E W

MY S T I F Y I N G T H E CO N C E P T O F CA P I T A L

73

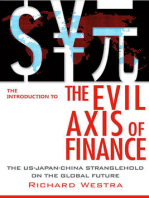

Table 1 Economic Performance in Selected Countries, 19752003, 2004

GDP/ population Country Hong Kong Singapore Bahamas South Korea Barbados Antigua and Barbuda Seychelles Trinidad and Tobago St. Kitts and Nevis Mexico Chile Botswana Mauritius Malaysia Thailand China Portugal Greece New Zealand Spain Canada Germany France United Kingdom United States 2 0 0 3 ( U.S. $ ) 22,987 21,492 16,571 12,634 9,708 9,629 8,610 8,007 7,397 6,121 4,591 4,372 4,274 4,187 2,305 1,100 14,161 15,608 19,847 20,404 27,079 29,115 29,410 30,253 37,648 Annual Growth Rate (%) 19752003 4.3 4.9 1.2 6.1 1.2 3.8 2.9 5.1 0.9 4.0 5.1 4.6 3.9 5.1 8.2 2.8 1.0 1.0 2.2 1.6 2.0 1.7 2.1 2.0 Annual Growth Rate (%) 19902003 2.1 3.5 0.3 4.6 1.4 1.6 2.2 3.2 3.1 1.4 4.1 2.7 4.0 3.4 2.8 8.5 2.2 2.1 2.1 2.4 2.3 1.3 1.6 2.5 2.1 GNI/ population 2004 (U.S.$) 26,810 24,220 14,920 13,980 9,270 10,000 8,090 8,580 7,600 6,770 4,910 4,340 4,540 4,650 2,540 1,290 14,350 16,610 20,310 21,210 28,390 30,120 30,090 33,940 41,400

Sources: United Nations Development Program 2005, table 14,26667. GNI = gross national

income, from World Bank 2006, 29293, 316.

63). Nevertheless, people are less inclined to save if the expected real return in interest is rendered negative by government controls on interest rates or by high and variable rates of inflation. 1 2 The incentive to save is also diminished by the insecurity of property created by civil wars, political instability, breakdown of law and order, inef12. For example, inflation rates in Peru, measured by the consumer price index, were 667 percent, 3,399 percent, and 7,482 percent in 1988, 1989, and 1990, respectively, and deposit interest rates were 162

V OLUME X I I I , N UMBER 1 , S UMMER 2 0 0 8

74

JAME S C. W. AHIAKPOR

f i cient administration of justice, rampant corruption of public of f i cials, theft, or armed

robbery. To the extent that price controls retard producers income-earning capacity, the y a l so r e tar d the g r ow th of s a vi ng i n an e c onom y, a s d o hi g h r a tes of i nc om e taxa ti on. Imp edim ents to foreig n e nte rpr ises inves tme nts in T hi rd Worl d countri e s also retard income creation there, hence retarding the rate of domestic savings. These c o nd i ti o ns a r e th e m o r e i m p or ta n t i m p e d i m e n ts t o e c o no m i c d e ve l op m e n t i n t he T hi r d Wor l d , w hi ch the i r g ove r nm ents s houl d b e ad vis ed to r em e d y. T h e g o ve r nm e n ts o f t h e l e s s -d e ve l op e d c o u nt r i e s m a y t a k e m a ny o t he r us e ful actions to facilitate their economic development, consistent with Adam Smith s elaboration in the W e al th of N ati on s. These actions include adoption of nondiscriminatory tariffs to facilitate free and ef f i cient international trade between their countri es and mor e-d eve lop ed c ountr ies, as wel l as am ong thems el ves; l im ite d gover nment spending, consistent with easy taxes and small budget de f i cits; and the provision of social infrastructure, including roads and bridges, appropriately paid for by user fees. T he se p r es cr i p tions a re w e ll know n i n the d e ve l opm ent-e c onom i cs l i te ra tur e. Their adoption by some countries in the Third World over the past half century or so, particularly in Southeast Asia, has yielded the expected positive results. Indeed, capitalism may be said already to have triumphed in Hong Kong, Singapore, South Korea, Taiwan, and the Bahamas, and may be well under way at various rates of development in such places as mainland China, Botswana, Chile, Malaysia, Mauritius, Seychelles, Thailand, and several island countries in the Caribbean, if we may judge by their levels of G DP or i nc ome pe r c ap i ta a nd the ir ra tes of a nnua l g r ow th s i nc e the m i d -1970s (see tab le 1). Inde ed, the i ncomes per c api ta of Singa pore and H ong Kong e xcee d thos e of P or tuga l , Gr e ec e , N ew Ze a la nd , a nd S p ai n, countr i es tha t d e S oto w ould include among the capitalist West. The incomes of the Bahamas and South Korea are not far behind. Thus, the data would appear to negate the subtitle of de Soto s book:

Why Capitalism Triumphs in the West and Fails Everywhere Else.

Moreover, not everyone welcomes capitalism or private enterprise as an acceptable form of economic orga niza ti on. S om e are strongl y averse to the i neq ual ity of

income distribution 1 3 that may accompany economic development through private

enterprise, 1 4 and others, under the inspiration of Marxist or Maoist philosophy, bepercent, 1,136 percent, and 2,440 percent, respectively (International Monetary Fund 2001). The rates of in f l ation fairly closely match the rates of currency creation in Peru for those three years: 568 percent, 1,437 percent, and 7,783 percent, respectively. T he negative real interest rates on deposits, roughly amounting to - 505 percent, - 2,263 percent, and - 5,042 percent, respectively, were far more discouraging to saving and capital formation than the lack of titles to anyone s property in Peru in those years.

13. I n c o m e d i s t r i b u t i o n is a misleading term because no one hands out to individuals their shares of national income. I n c o m e c r e a t i o n better describes what goes on: people exercising different capabilities in creating their own incomes.

14. Income inequality has increased in China since the government gave up on Maoist economic organizatio n and op ened up th e ec ono m y to pr ivat e ente rprise , pa rtic ula rl y for eign dir ect inve stm ent. Ch ina s Gini c oe f f i cient is r epor ted t o h av e r ise n f ro m 2 8. 8 in 19 81 to 3 8. 8 in 1 9 95 (Wo rld Bank study c ited in M e i e r a nd R a uc h 2 0 0 5 , 4 7 3) . A l th o ug h m os t C h in e s e ha v e ob vi o u sl y b e ne f i te d f ro m t h e n ew ec o no m ic

TH E IN D E P E N D E N T RE V I E W

MY S T I F Y I N G T H E CO N C E P T O F CA P I T A L

75

belief that private property derives from theft and that the capitalist system is a mechanism for the exploitation of the poor in society views that de Soto himself recounts (2 12 18). Thus, it is to be expected that different governments around the world may choose different approaches to economic organization, obtaining different results. As Ricardo acutely observes, following J-B. Say, it is not the province of the Political Economist to advise: he is to tell you how you may become rich, but he is not to advise you to prefer riches to indolence, or indolence to riches (1951 , 2:338). M or e ove r , s oc i e t i e s i n w h i c h the d r i ve to b e c om e r ic h thr oug h p r od uc ti on i s n ot strong can hardly be expected to choose, individually or generally through their gove rnm ents, the path to b e comi ng wea lthy. It would have been helpful had de Soto s belief that capitalism is the only game in town cap able of cr eating econom ic p rosp eri ty al ong with fr eed om, com passi on for the poor, respect for the social contract, and equal opportunity (228) led him to counter Marxist-inspired misrepresentations of the process of economic development in the Third World, especially of the dependency theory type. Instead, he restates those misrepresentations: capitalism is a transfer of property from poorer to richer countries and. . . Western private investment in developing nations is nothing short of a massive takeover of their resources by multinationals (214). In contrast, Joan Robinson aptly declares that as we see nowadays in South-East Asia or the Caribbean, the misery of being exploited by capitalists is nothing compared to the misery of not being exploited at all (1962, 46).1 5 De Soto might have illustrated Robinson s observation with data showing that since the 1960s countries that have been more open to international trade and foreign direct investment have grown faster and seen a greater reduction in absolute poverty than the socialist ones have. Instead, he treats Marxist-inspired views as though they have validity. He also thinks Marx s insights into capital, as George Soros recently observed, are often more sophisticated than those of Adam Smith (214), but his research would have been better served had he consulted Smith s Wealth of Nations more carefully or Alfred Marshall s Princ iples on the r e l a ti v e m e r i ts o f A d a m S m i th, Da vi d R i c a r d o, a nd J . S . M i l l s d e f i ni ti on o f

cap ita l, i ts source , and i ts rol e i n ec onomic d eve lopme nt.

Smi th wa rns about the knowledg e pr obl em, as Haye k (1945) subseque ntly called it, and urges governments to refrain from attempting to direct private investors i n how the y s houl d e mp l oy the i r c a pi ta ls : What is the species of domestic industry which his capital can employ, and of which the produce is likely to be of the greatest value, every individual, it is evident, can, in his local situation, judge much better than any statesm a n or law g i ver c a n d o for hi m . T he s tate sm a n, w ho s houl d a tte mp t to

framework, and absolute poverty has declined in that country, some may yet be inclined to point to the increased income inequality as an undesirable feature of the new system. 15. Robinson had strong Marxist sympathies, nevertheless. See Ahiakpor 1985 for a counter to dependency theory arguments.

V OLUME X I I I , N UMBER 1 , S UMMER 2 0 0 8

76

JAME S C. W. AHIAKPOR

direct private people in what manner they ought to employ their capitals, would not only load himself with a most unnecessary attention, but assume an authority which could safely be trusted, not only to no single person, but to no counsel or senate whatever, and which would no-where be so dangerous as in the hands of a man who had folly and presumption enough to fanc y himse lf f i t to exe rcise it. ([1776] 1976, 1:478) Disregarding the knowledge problem for regulators in a country, George Soros advoc ates the es tab lis hme nt of a w orl d bod y to r egulate capi tal inves tme nts through a col lec ti ve dec isi on-making mechanism : T o put the matter sim pl y, mar ke t forc e s, if they are given complete authority even in the purely economic and f i nancial arenas, p r od uc e c ha os a nd c o ul d ul t i m a t e l y l e a d t o t he d ow nf a l l o f t he g l ob a l c a p i t a l i s t system. This is the most important practical implication of my argument in this book (1998, xxvii) . 1 6 And de S oto f i nds no grounds on whi ch to obje ct to Sor os s sug gested scheme. Ba d p ol ic y c hoic es b y g over nm e nts i n the l e ss -d eve lop e d c ountr i es c er ta i nly e x p l ai n for the m os t pa r t the e x te nt of the ir p e op le s p ove r ty. H ow the c hoic e of growth-promoting policies has yielded the expected results in the more-developed countries therefore merits constant illustration. Yet such policies do not include massive government programs to hand to the poor paper titles to whatever properties they may own. In any case, those who f i nd the gains of acquiring paper titles to be worth the costs of registering their properties may do so on their own. Although paper titles may facilitate loan applications, they can hardly be the primary source of capital for e c on om i c d e v e l op m e n t i n a n y c ou n tr y . T ha t s o ur c e m us t b e i n c r e a s e d d o m e s ti c savings.

References

Ahiakpor, James C. W. 1985. The Success and Failure of Dependency Theory: The Experience of Ghana. I nt e r n a t i o n a l O r g a n i za t i o n 39, no. 3 (summer): 5 35 52.

. 199 5. A P ar adox of Thr ift or Keynes s M isr epr esentati o n of Saving in th e Class ical

Theory of Growth? Southern Econo mic Journ al 62 (July): 16 3 3.

. 1997. Austrian Capital Theory: Help or Hindrance? Journal of the History of Economic

T h o ug ht 19 (fall): 261 85.

Alston, Lee J. 1984. Farm For eclosur e M orator ium Legislation: A Lesson fr om the P ast.

America n Economic Review 74, no. 3 (June): 445 57.

Atwood, David A. 1990. Land Registration in Africa: The Impact on Agricultural Production.

W orld Develop ment 18 (May): 659 71.

Baetjer , Howard, Jr ., and M ichael I. Lineberr y. 2003. The Mystery of Capital and Economic

16. Soros apparently has a low opinion of laissez- faire policies, which he calls market fundamentalism (1998, xx).

TH E IN D E P E N D E N T RE V I E W

MY S T I F Y I N G T H E CO N C E P T O F CA P I T A L

77

Calculation: How de Sotos Insights Illuminate the Austrian Case for Private Property. Journal of Private Enterprise 18, no. 2 (spring): 5566. Bauer, P. T. 1981. Equality, the Third World, and Economic Delusion. London: Methuen. Baumol, William J. 1977. Says (at Least) Eight Laws, or What Say and James Mill May Really Have Meant. Economica 44 (May): 14562. Besley, Timothy. 1995. Property Rights and Investment Incentives: Theory and Evidence from Ghana. Journal of Political Economy 103, no. 5 (October): 90337. Bhm-Bawerk, Eugen von. [1890] 1970. Capital and Interest: A Critical History of Economic Theory. Translated by William Smart. New York: Kelley. Buch, Claudia. 2002. De Soto, Hernando, The Mystery of Capital: Why Capitalism Triumphs in the West and Fails Everywhere Else. WeltwirtschaftlichesArchiv Review of World Econom

ics 138, no.1: 16265. Clark, J. B. [1900] 1938. The Distribution of W ealth. New York: Macmillan. Clift, Jeremy. 2003. Hearing the Dogs Bark. Finance and Development 40, no. 4 (December): 811. Coase, Ronald H. 1937. The Nature of the Firm. Eco no mic a, new series, 4 (November): 386405. Culpepper, Roy. 2002. Demystifying Hernando de Soto: A Review of The Mystery of Capital. Available at http://www.nsi-ins.ca/english/pdf/desoto.pdf. De Soto, Hernando. 2000. The Mystery of Capital: Why Capitalism Triumphs in the West and Fails Everywhere Else. New York: Basic Books. Easterly, William. 2003. Can Foreign Aid Buy Growth? Journal of Economic Perspectives 17, no. 3 (summer): 2348. Galiani, Sebastian, and Ernesto Schargrodsky. 2005. Property Rights for the Poor: Effects of Land Titling. Available at: http://www.utdt.edu/departamentos/empresarial/cif/cif.htm. Gilbert, Alan. 2002. On The Mystery of Capital and the Myths of Hernando de Soto. International Development Planning Review 24 (February): 119. Goldsmith, Raymond W. 1969. Financial Structure and Development. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press. Gwartney, James D., Richard L. Stroup, Russell S. Sobel, and David A. Macpherson. 2006. Macroeconomics: Private and Public Choice. 11th ed. Mason, Ohio: Thomson. Hayek, Friedrich A. 1941. The Pure Theory of Capital. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul. . 1945. The Use of Knowledge in Society. American Economic Review 35, no. 4 (September): 5 1930. Hernando de Soto. 2007. W i k i p e d i a . Available at: http://www.wikipedia.com. International Monetary Fund. 2001. International Financial Statistics Yearbook, 2001. Washington, D.C.: International Monetary Fund. Jacoby, Hanan G., and Bert Minten. 2007. Is Land Titling in Sub-Saharan Africa CostEffective? Evidence from Madagascar. World Bank Economic Review 21, no. 3: 46185. Keynes, J. M. [1936] 1976. The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money. Paperbound ed. London: Macmillan.

V OLUME X I I I , N UMBER 1 , S UMMER 2 0 0 8

78

JAME S C. W. AHIAKPOR

Knight, Frank H. 1935. Professor Hayek and the Theory of Investment. E c o n o mi c J o u r n a l 45 (March): 77 94.

. [1933] 1967. T h e E c o n o m i c O r g a n i z a t i o n . New York: Augustus M. Kelley.

Levine, Ross. 1997. Financial Development and Economic Growth: Views and Agenda. J o u r nal

of Economic Literature 35 (June): 688 726.

Libecap, Gary D. 2001. Review of The Mystery of Capital: Why Capitalism Triumphs in the West

and Fails Everywhere Else, by Hernando de Soto. Journal of Economic History 61, no. 4:

1166 168.

Marshall, Alfred. [1920] 1990. P ri nc ip l es of Ec o no mics. 8th ed. Philadelphia: Porcupine Press. McKinnon, Ronald I. 1973. Money and Capital in Economic Development. Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution. Meier, Gerald M., and James E. Rauch. 2005. Leading Issues in Economic Development. 8th ed. New York: Oxford University Press. Mill, John S. 1963 88. C o l l e c t e d W o r k s . 32 vols. Edited by J. M. Robson. Toronto: University

of Toronto Press. Miranda, Liliana. 2002. A New Mystery from de Soto? A Review of T h e Myst e ry of Ca pit a l.

E n v i r o n me n t a n d Ur b a n i za t i o n 14, no. 1 (April): 263 64.

Morris, Andrew P. 2007. Miners, Vigilantes, and Cattlemen: Property Rights on the Western Frontier. F r e e m a n 57, no. 3 (April): 25 30.

Pal, Anirban. 2003. Review of The Mystery of Capital: Why Capitalism Triumphs in the West and

Fails Everywhere Else, by Hernando de Soto. Development and Change 34, no. 1 (January):

19 3 94.

Perkins, Dwight H., Steven Radelet, and David Lindauer. 2006. Economics of Development. 6th ed. New Yor k: Nor ton. Pigou, A. C. 1927. I n d u s t r i a l F l u c t u a t i o n s . London: Macmillan. Ricardo, David. 1951 . W o r k s a n d Co r r e s p o n d e n c e . 10 vols. Edited by Pierro Sraffa. Cam

bridge, U.K.: Cambr idge University Press. Robinson, Joan. 1962. E c o n o mi c P h i l os o p h y . Harmondsworth, U.K.: Penguin. Rosenberg, Matthew J. 2002. Review of The Mystery of Capital: Why Capitalism Triumphs in

the West and Fails Everywhere Else, by Hernando de Soto. International Affairs 78, no. 1

(January): 174. Samuelson, Robert J. 2001. The Spirit of Capitalism. F o r e i g n A f f a i r s 80, no. 1 (January Feb

ruary): 205 11.

Smith, Adam. [1776] 1976. T h e W e a l t h o f Na t i o n s . 2 vols. Edited by E. Cannan. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Soros, George. 1998. T h e Cris is of Gl o b al Ca pit al is m. New York: Public Affairs. Sowell, Thomas. 2000. A Gem of a Book. Review of T h e M ys t er y o f Ca p i t a l , by Hernando de Soto. J e w i s h W o r l d R e v i e w (December 18 [21 Lislev 5761]) Available at: http:// www.jewishwor ldreview.com/cols/sowell121800.asp. Thomas, Jim. 2002. Review of The Mystery of Capital: Why Capitalism Triumphs in the West

and Fails Everywhere Else, by Hernando de Soto. Journal of Latin America Studies 34

TH E IN D E P E N D E N T RE V I E W

MY S T I F Y I N G T H E CO N C E P T O F CA P I T A L

79

(Februar y): 189 91.United Nations D evelopment Pr ogramme (UND P). 2005. H u m a n

Development Report 2005. New York: UNDP.

Van Tassel, Eric. 2004. Credit Access and Transferable Land Rights. Ox f o r d Ec o n o mi c P a p e r s 56: 151 66.

Woodruff, Christopher. 2001. Review of de Soto s The Mystery of Capital. Journal of Economic

L i t e r a t u r e 39, no. 4 (December): 1215 223.

World Bank. 2006. W o r l d De v el o p me n t Re p o r t 2 0 0 6 . Washington, D.C.: World Bank.

Acknowledgments: An earlier version of this article was presented at the Western Economic Association

International Conference, Seattle, June 29 July 3, 2007, and at the Workshop for Economic R esearch, Department of Economics, California State University, East Bay, November 14, 2007. I thank Scott Sambucci and other commentators at these presentations and two anonymous referees for their comments and suggestions, without implicating them in any errors that are mine. I also thank the College of Business and Econ om ics at C ali fo rni a Stat e Unive rsity , Ea st Bay, fo r a on e- c ours e r ele as e tim e that a ided th is research.

V OLUME X I I I , N UMBER 1 , S UMMER 2 0 0 8

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- Critiqueof de SotoDokumen27 halamanCritiqueof de SotoDavid Jonathan Rosado EscobarBelum ada peringkat

- ESFN AERUS Gilbert Mystery Capital PDFDokumen19 halamanESFN AERUS Gilbert Mystery Capital PDFJennifer NoelBelum ada peringkat

- Hernando de Soto The Mystery of Capital PDFDokumen7 halamanHernando de Soto The Mystery of Capital PDFJaime Andrade100% (4)

- The impact of Hernando de Soto's The Mystery of Capital after ten yearsDokumen8 halamanThe impact of Hernando de Soto's The Mystery of Capital after ten yearsireqBelum ada peringkat

- The Mystery of Capital PaperDokumen8 halamanThe Mystery of Capital PaperMatt LewisBelum ada peringkat

- How Formal Property Rights Can Help Developing EconomiesDokumen8 halamanHow Formal Property Rights Can Help Developing Economiesw.riskieBelum ada peringkat

- Goldfinch 2015. Property Rights and The Mystery of Capital. A Review of de Soto's Simplistic Solution To DevelopmentDokumen10 halamanGoldfinch 2015. Property Rights and The Mystery of Capital. A Review of de Soto's Simplistic Solution To DevelopmentneverwritBelum ada peringkat

- Summary of de SotoDokumen6 halamanSummary of de SotoUduak Ukpong100% (1)

- The Nation State in The Era of Globalization - Some ChallengesDokumen10 halamanThe Nation State in The Era of Globalization - Some ChallengesDannaiBelum ada peringkat

- Globalization PP 6 PagesDokumen13 halamanGlobalization PP 6 PagesRussell MonroeBelum ada peringkat

- Glover Property Rights PEPD 2023 - VfinalDokumen48 halamanGlover Property Rights PEPD 2023 - Vfinalalejandraoo221Belum ada peringkat

- The Mystery of Capital and the Construction of Social RealityDari EverandThe Mystery of Capital and the Construction of Social RealityBelum ada peringkat

- 1989 Evans - Predatory-Developmental - 1989Dokumen28 halaman1989 Evans - Predatory-Developmental - 1989Софья ВахрушеваBelum ada peringkat

- The Globalization Paradox Review of Dani Rodrik, The Globalization Paradox Democracy and The Future of The World EconomyDokumen4 halamanThe Globalization Paradox Review of Dani Rodrik, The Globalization Paradox Democracy and The Future of The World EconomyWesley SupervilleBelum ada peringkat

- Jeremy Clift Interviews Development Guru Hernando de SotoDokumen4 halamanJeremy Clift Interviews Development Guru Hernando de SotoPearl SkyBelum ada peringkat

- GLOBALIZACIÓN-Globalization, Inequalities and Justice-Elisabetta Di CastroDokumen15 halamanGLOBALIZACIÓN-Globalization, Inequalities and Justice-Elisabetta Di CastroNorman AlburquerqueBelum ada peringkat

- Kamla Nehru College Southcampus History-Assignment: Suneha Sharma MA Previous 2nd Sem Title-Dawn &dusk of EconomyDokumen5 halamanKamla Nehru College Southcampus History-Assignment: Suneha Sharma MA Previous 2nd Sem Title-Dawn &dusk of EconomyTaza KhabarBelum ada peringkat

- The Race To The Bottom Hypothesis: An Empirical and Theoretical ReviewDokumen20 halamanThe Race To The Bottom Hypothesis: An Empirical and Theoretical ReviewBenjamin Goo KWBelum ada peringkat

- The Mystery of Capital: Ruben AlvaradoDokumen6 halamanThe Mystery of Capital: Ruben AlvaradoRuben AlvaradoBelum ada peringkat

- Globalization and Darwinism: Limitations of Applying Biological Evolution to Economic ChangeDokumen9 halamanGlobalization and Darwinism: Limitations of Applying Biological Evolution to Economic ChangeAllen Salvador SaulongBelum ada peringkat

- Subjek Hukum InternasionalDokumen52 halamanSubjek Hukum InternasionalRizqi Bangun LestariBelum ada peringkat

- The Incredible Hoax (How Monetary System Causes World Catastrophes) (2003)Dokumen143 halamanThe Incredible Hoax (How Monetary System Causes World Catastrophes) (2003)Douglas Shearer100% (1)

- NWO-Summary FinalDokumen23 halamanNWO-Summary FinalRavi ShankarBelum ada peringkat

- Mysteries of Capital or Mystification of Legal Property?Dokumen6 halamanMysteries of Capital or Mystification of Legal Property?chanvierBelum ada peringkat

- W (H) Ither The Nation-State? National and State Identity in The Face of Fragmentation and GlobalisationDokumen24 halamanW (H) Ither The Nation-State? National and State Identity in The Face of Fragmentation and GlobalisationSimona CapslockBelum ada peringkat

- Literature Review GlobalizationDokumen7 halamanLiterature Review Globalizationlbiscyrif100% (1)

- Hernando de Soto - The Other PathDokumen11 halamanHernando de Soto - The Other PathJehan SiregarBelum ada peringkat

- Uncertainty and Orientation to the Future in Northeast BrazilDokumen13 halamanUncertainty and Orientation to the Future in Northeast BrazilCristóbal Karle SaavedraBelum ada peringkat

- Could The Blockchain Empower The Poor and Unlock Global Growth?Dokumen4 halamanCould The Blockchain Empower The Poor and Unlock Global Growth?api-302100826Belum ada peringkat

- The Deficit Myth: Modern Monetary Theory and The Birth of The People's EconomyDokumen20 halamanThe Deficit Myth: Modern Monetary Theory and The Birth of The People's EconomyjacintoBelum ada peringkat

- Unit 3 Changing Role of The State: Issues and Challenges: StructureDokumen18 halamanUnit 3 Changing Role of The State: Issues and Challenges: StructureSai Anil SBelum ada peringkat

- Don DeLillo's Critique of Rogue Capitalism in 'CosmopolisDokumen31 halamanDon DeLillo's Critique of Rogue Capitalism in 'CosmopolisSuerry ZhouBelum ada peringkat

- Rogerian EssayDokumen7 halamanRogerian Essayapi-638941697Belum ada peringkat

- Cultures of FinanceDokumen6 halamanCultures of Financeabc_2522Belum ada peringkat