Why Nations Fail theory fails to explain India and China

Diunggah oleh

scribd_728Judul Asli

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Why Nations Fail theory fails to explain India and China

Diunggah oleh

scribd_728Hak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Why Nations Fail And why India and China dont fit the story

Why Nations Fail by Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson is becoming a mustread for development economists. But this column argues that the central thesis of the book fails to explain two big development stories: those of India and China. Why Nations Fail, by Professors Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson has deservedly gained right of entry to the pantheon of big books on economic development. Like the pantheons other occupants, most recently Jared Diamonds Guns, Germs and Steel, and Ian Morriss Why the West Rules for Now, Acemoglu and Robinsons work tackles one of the biggest questions facing humanity: why some countries are rich and others poor. The book is daringly ambitious in the simplicity of its answer; and yet its scholarship is serious and it offers a deep and plausible insight about development. Why Nations Fail does not draw upon as breathtakingly broad a range of disciplines as those in either Diamonds or Morriss work. This stems from the different time scales of inquiry. Diamond starts the development clock around 13,000 BCE, and Morris more than a million years ago. But the Acemoglu and Robinson story begins only about 700-800 years ago, necessarily ruling out from their account evidence from genetics, evolution, paleo-biology, and archaeology, which are staples in both Diamond and Morris. Colonialism and development Why Nations Fail is both a derivative and a development of an academic paper that Acemoglu and Robinson co-authored in 2000 with MIT Professor Simon Johnson (full disclosure: Professor Johnson is my colleague and co-author). In The Colonial Origins of Comparative Development (Acemoglu et al. 2000), one of the most-widely cited and justly influential academic papers on economic development in the past fifteen years, the trio argued that the quality of economic institutions was the key long-term determinant of economic prosperity (measured broadly in terms of per capita GDP). Good economic institutions protected property rights and guaranteed the sanctity of contracts,

which are key prerequisites for private sector investment and entrepreneurship. In Why Nations Fail, however, Acemoglu and Robinson go one step further in arguing that economic institutions in turn are determined by politics. The more concentrated political power is, the more a small group in society tries to extract wealth for itself to the detriment of the rest: this is a world of extractive institutions. Conversely, dispersed political power as exists in democracies is conducive to contestability and competition, which create the conditions for broadly shared prosperity (a world of inclusive institutions). Thus, Acemoglu and Robinsons parsimonious explanation for the disparities in wealth across the world is: political institutions. There have been many insightful reviews and critiques of the book by Frank Fukuyama, Jared Diamond, Martin Wolf and the Economist1, as well as thoughtful responses from these authors on their respective blogs. My aim is not so much to review all aspects of the book as to offer one perspective on it. Why Nations Fail -- And why India and China dont fit the story Invoking the very spirit of Occams Razor that imbues the book, I would like to explain Why Nations Fail in light of the figure below: economic development (proxied by per capita GDP) is measured on a y-axis and that an index of political institutions (higher values denote more representative or inclusive ones) on the x-axis. The choice of axes is very important because the book asserts that causation runs from politics (the independent variable on the xaxis) to economic development (the dependent variable on the y-axis). The authors are unsympathetic to causation running the other way. That is, they reject the modernisation hypothesis, which asserts that improvements in standards of living will lead to more democratic politics, stemming for example, from increased demand for political freedom and participation. For Acemoglu and Robinson, political institutions bear the deep imprints of history, and although they are not immutable, their susceptibility to change induced by economic development is limited. Figure 1. Why Nations Fail in a single picture

This figure is based on a sample of 141 countries (excluding the major oil exporters). Data are for 2009. GDP per capita data are from the Penn World Tables (version 7), and data for the democracy index are from the Polity IV database. The upward-sloping line in our figure reflects a strong relationship (on average) between political institutions and economic development, validating the central argument of Why Nations Fail. However, India and China stand as outliers (they are far away from the line drawn by Acemoglu and Robinsons function). And the interesting thing is that each of these countries is an exception to, or even a challenge to, their thesis in opposite ways. India (which is way below the line) is too economically underdeveloped given the quality of its political institutions, and China (which is well above the line) is too rich given its lack of democratic institutions. Acemoglu and Robinson can mount two defenses. First, they can contend that all countries should be treated equally because every political unit is only one experiment, and thus one data point (regardless of size). After all, their thesis holds true for a vast majority of countries (that is why the line is upward sloping). Therefore the authors must be allowed some exceptions, given they have daringly embraced a mono-causal explanation of what is clearly a complex relationship between politics and economics. Still, at a basic level, explaining economic development while leaving out one-third of humanity from it is not entirely satisfying. Second, Acemoglu and Robinson can contend that theirs is a claim about the

medium to long run. These horizons are never clearly specified but would rule out criticisms based on relationships observed for only, say, 20 to 30 years. Reproducing the figure for 1980, for example, would show China near the line (although India would still be far from it). The Chinese anomaly is a result of the past 30 years of astonishingly rapid growth. Wait for another 20 years, Acemoglu and Robinson might plead, and the anomalies in the figure will fade away or at least move in the direction predicted in their book. This defense is more problematic. Suppose that we were to re-visit the book in 2030. What would have to happen to China and India for them to be consistent with the relationship predicted by Acemoglu and Robinson? India in 20 years would have to slide into authoritarian chaos and become the equivalent of countries such as Venezuela today politically, or it would have to boom to become the equivalent of countries such as China in terms of standards of living. Conversely, China would either have to become a near-Jeffersonian democracy or suffer a dramatic collapse in output (that is, post negative growth). None of these four outcomes is impossible, but none is likely either. Thus, even 20 years from now, China and India are unlikely to be adequately explained by Acemoglu and Robinsons thesis. But one could make an even stronger critique of the book. Even if China and India were to move rapidly in the direction predicted over the next 20 years, it would still beg the question of how China managed to sustain 30 to 50 years of historically unprecedented rapid growth (and poverty reduction) under repressive political conditions and how India squandered 30 or 40 years of democracy with its Hindu rate of growth. Of course, there are answers but the point is that they would have to be different from, and even orthogonal to, the central thesis of Why Nations Fail. In other words, the inability of Acemoglu and Robinson to explain the development trajectories of these two large countries is a fault not of their rich and excellent book but of the unusual, uncooperative reality of Chinese and Indian history. This column was originally published in American Interest. Notes: 1. Diamond (2012), Economist (2012), Fukuyama (2012) and Wolf (2012).

Further reading Acemoglu, D, S Johnson and J Robinson (2000), The Colonial Origins of Comparative Development: An Empirical Investigation, The American Economic Review, 91(5):1369-1401, published 2001. Acemoglu, D and J Robinson (2012), Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity and Poverty, Profile Books. Diamond, J (1998), Guns, Germs and Steel: A short history of everybody for the last 13,000 years, Vintage. Diamond, J (2012), What Makes Countries Rich or Poor?, The New York Review of Books, 7 June. Economist (2000), The Big Why [1], 10 March. Fukuyama, F (2012), Acemoglu and Robinson on Why Nations Fail, theamerican-interest.com, 26 March. Morris, I (2010), Why The West Rules For Now: The Patterns of History and what they reveal about the Future, Profile Books. Wolf, M (2012), The wealth of nations: Do political institutions hold the key to a countrys economic success?, Financial Times, 3 March.

1. http://www.economist.com/node/21549911

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- Book Review - ''THE UN IN EAST TIMOR - Building Timor Leste, A Fragile State by DR Juan Federer''Dokumen4 halamanBook Review - ''THE UN IN EAST TIMOR - Building Timor Leste, A Fragile State by DR Juan Federer''jf75Belum ada peringkat

- Regionalism - A Stepping Stone or A Stumbling Block in The Process of Global Is at IonDokumen18 halamanRegionalism - A Stepping Stone or A Stumbling Block in The Process of Global Is at IonAulia RahmadhiyanBelum ada peringkat

- Why Do States Pursue Nuclear Weapons? A Framework for Israel, Iran and Saudi ArabiaDokumen19 halamanWhy Do States Pursue Nuclear Weapons? A Framework for Israel, Iran and Saudi ArabiaSyeda Rija Hasnain Shah Treemze100% (1)

- Absolute Advantage: Origin of The TheoryDokumen5 halamanAbsolute Advantage: Origin of The TheoryactivenavaneethanBelum ada peringkat

- The State in Africa The Politics of The BellyDokumen27 halamanThe State in Africa The Politics of The BellymichellenadeemBelum ada peringkat

- Egypt's New Regime and The Future of The U.S.-Egyptian Strategic RelationshipDokumen62 halamanEgypt's New Regime and The Future of The U.S.-Egyptian Strategic RelationshipSSI-Strategic Studies Institute-US Army War CollegeBelum ada peringkat

- Actorsofinternationalrelations 120520143103 Phpapp01Dokumen19 halamanActorsofinternationalrelations 120520143103 Phpapp01Madeeha AnsafBelum ada peringkat

- USAID Fragile States StrategyDokumen28 halamanUSAID Fragile States Strategysachin_sacBelum ada peringkat

- GFPP2223 Foreign Policy: School of International Studies Universiti Utara MalaysiaDokumen26 halamanGFPP2223 Foreign Policy: School of International Studies Universiti Utara MalaysiaSultan MahdiBelum ada peringkat

- Failing, Failed, and Fragile States Conference ReportDokumen110 halamanFailing, Failed, and Fragile States Conference ReportestrellitaaliaBelum ada peringkat

- Corbett in Orbit - A Maritime Model For Strategic Space TheoryDokumen16 halamanCorbett in Orbit - A Maritime Model For Strategic Space TheoryCarlos Serrano FerreiraBelum ada peringkat

- Building Peace and Security in AfricaDokumen263 halamanBuilding Peace and Security in AfricaMuhammad Abdurrahman Ghofiqi0% (1)

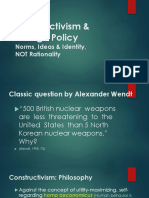

- 04-Constructivism - Foreign PolicyDokumen21 halaman04-Constructivism - Foreign PolicyIlham Dary AthallahBelum ada peringkat

- Yarger Chapter 3Dokumen10 halamanYarger Chapter 3BenBelum ada peringkat

- Theories of International Relations: ConstructivismDokumen18 halamanTheories of International Relations: ConstructivismMarienelle TalagonBelum ada peringkat

- Preventing Military InterventionsDokumen40 halamanPreventing Military InterventionsArmand G PontejosBelum ada peringkat

- 1890 - Alfred Thayer Mahan - On Sea PowerDokumen2 halaman1890 - Alfred Thayer Mahan - On Sea Poweroman13905Belum ada peringkat

- Sunset For The Two-State Solution?Dokumen8 halamanSunset For The Two-State Solution?Carnegie Endowment for International Peace100% (2)

- Boundary Disputes and State Failure A Case Study of SomaliaDokumen222 halamanBoundary Disputes and State Failure A Case Study of SomaliaScholar Akassi100% (1)

- Fukuyama's Approach to Measuring GovernanceDokumen19 halamanFukuyama's Approach to Measuring GovernanceAlex100% (1)

- Is Clausewitz Still Relevant To Today's Security Environment?Dokumen19 halamanIs Clausewitz Still Relevant To Today's Security Environment?Marta AliBelum ada peringkat

- Tumultuous Tides: Explaining and Understanding The Perpetuation of The South China Sea ConflictDokumen64 halamanTumultuous Tides: Explaining and Understanding The Perpetuation of The South China Sea ConflictJerome BernabeBelum ada peringkat

- Realism/Realist Theory (Chủ Nghĩa Hiện Thực)Dokumen34 halamanRealism/Realist Theory (Chủ Nghĩa Hiện Thực)Thư TrầnBelum ada peringkat

- US Hegemony in A Unipolar WorldDokumen4 halamanUS Hegemony in A Unipolar WorldZafar MoosajeeBelum ada peringkat

- Thayer Regional Security and Defence DiplomacyDokumen16 halamanThayer Regional Security and Defence DiplomacyCarlyle Alan Thayer100% (1)

- Mearsheimer Vs WaltzDokumen3 halamanMearsheimer Vs WaltzKelsieBelum ada peringkat

- Alesina, Alberto Et Al. (2010) - Fiscal Adjustments Lessons From Recent HistoryDokumen18 halamanAlesina, Alberto Et Al. (2010) - Fiscal Adjustments Lessons From Recent HistoryAnita SchneiderBelum ada peringkat

- Foreign Policy of Small States NoteDokumen22 halamanForeign Policy of Small States Noteketty gii100% (1)

- Actors Arnold WolfersDokumen16 halamanActors Arnold Wolferssashikumar1984Belum ada peringkat

- Identity Formation and The International StateDokumen14 halamanIdentity Formation and The International StateGünther BurowBelum ada peringkat

- 1 Rosenau Governance-in-the-Twenty-first-Century PDFDokumen32 halaman1 Rosenau Governance-in-the-Twenty-first-Century PDFAbigail AmestosoBelum ada peringkat

- British Media Control During the Falklands WarDokumen6 halamanBritish Media Control During the Falklands WarSean SmithBelum ada peringkat

- Realist Thought and Neorealist TheoryDokumen9 halamanRealist Thought and Neorealist Theoryapto123Belum ada peringkat

- Small States in The International System PDFDokumen4 halamanSmall States in The International System PDFLivia StaicuBelum ada peringkat

- ADDING HEDGING TO THE MENUDokumen56 halamanADDING HEDGING TO THE MENUchikidunkBelum ada peringkat

- Vietnam's Strategic Hedging Vis-A-Vis China - The Roles of The EU and RUDokumen21 halamanVietnam's Strategic Hedging Vis-A-Vis China - The Roles of The EU and RUchristilukBelum ada peringkat

- David Laven, Lucy Riall - Napoleon's Legacy - Problems of Government in Restoration Europe (2000)Dokumen307 halamanDavid Laven, Lucy Riall - Napoleon's Legacy - Problems of Government in Restoration Europe (2000)Yuri SilvaBelum ada peringkat

- Elements of National PowerDokumen20 halamanElements of National Powerzunaira Khalid100% (1)

- Failing To Mass: Shortfalls in The Joint Operational Planning Process (Davis)Dokumen12 halamanFailing To Mass: Shortfalls in The Joint Operational Planning Process (Davis)Ian DavisBelum ada peringkat

- ROTBERG - Robert I.the New Nature of Nation-State FailureDokumen12 halamanROTBERG - Robert I.the New Nature of Nation-State FailureCamilla RcBelum ada peringkat

- Neorealism and NeoliberalismDokumen18 halamanNeorealism and NeoliberalismFarjad TanveerBelum ada peringkat

- Recovering American LeadershipDokumen15 halamanRecovering American Leadershipturan24Belum ada peringkat

- The Youth Bulge in Egypt - An Intersection of Demographics SecurDokumen18 halamanThe Youth Bulge in Egypt - An Intersection of Demographics Securnoelje100% (1)

- Categories of PowerDokumen1 halamanCategories of PowerCEMA2009Belum ada peringkat

- FDR's First Inaugural Address: A Rhetorical Analysis of His Use of Ethos, Pathos and LogosDokumen10 halamanFDR's First Inaugural Address: A Rhetorical Analysis of His Use of Ethos, Pathos and LogosLauraBelum ada peringkat

- Kugler and Organski PDFDokumen13 halamanKugler and Organski PDFMauricio Padron100% (1)

- Exploring Indigenous Approaches To Peacebuilding: The Case of Ubuntu in South AfricaDokumen14 halamanExploring Indigenous Approaches To Peacebuilding: The Case of Ubuntu in South AfricaAbdul Karim Issifu100% (2)

- Campaigns: The Essence of Operational Warfare: Ronald M. D'AmuraDokumen11 halamanCampaigns: The Essence of Operational Warfare: Ronald M. D'AmuraWinston CuppBelum ada peringkat

- Pandora's Box: Youth at A Crossroad - Emergency Youth Assessment On The Socio-Political Crisis in Madagascar and Its ConsequencesDokumen29 halamanPandora's Box: Youth at A Crossroad - Emergency Youth Assessment On The Socio-Political Crisis in Madagascar and Its ConsequencesHayZara Madagascar100% (1)

- Girotra Vinay Civil-Military RelationsDokumen11 halamanGirotra Vinay Civil-Military Relationsvkgirotra100% (5)

- Conserving and Valuing Ecosystem Services and Biodiversity Economic Institutional and Social ChallengesDokumen433 halamanConserving and Valuing Ecosystem Services and Biodiversity Economic Institutional and Social ChallengesArdibel Villanueva100% (1)

- How Relevant Carl Von Clausewitz StrategDokumen8 halamanHow Relevant Carl Von Clausewitz StrategBagus SutrisnoBelum ada peringkat

- Medhene TadesseDokumen170 halamanMedhene TadesseSamson Wolde0% (1)

- Snyder Security Dilemma in AllianceDokumen2 halamanSnyder Security Dilemma in AlliancemaviogluBelum ada peringkat

- Globalization: The Paradox of Organizational Behavior: Terrorism, Foreign Policy, and GovernanceDari EverandGlobalization: The Paradox of Organizational Behavior: Terrorism, Foreign Policy, and GovernanceBelum ada peringkat

- Waltz 1979, p.123 Waltz 1979, p..124 Waltz 1979, p.125 Waltz 1979, p.125 Waltz 1979, p.127Dokumen5 halamanWaltz 1979, p.123 Waltz 1979, p..124 Waltz 1979, p.125 Waltz 1979, p.125 Waltz 1979, p.127TR KafleBelum ada peringkat

- Divided Dynamism: The Diplomacy of Separated Nations: Germany, Korea, ChinaDari EverandDivided Dynamism: The Diplomacy of Separated Nations: Germany, Korea, ChinaBelum ada peringkat

- Pakistan-The Most Dangerous Place in The WorldDokumen5 halamanPakistan-The Most Dangerous Place in The WorldwaqasrazasBelum ada peringkat

- Introduction To RealismDokumen4 halamanIntroduction To Realismayah sadiehBelum ada peringkat

- HCS AuditLogReferenceGuide hc2132Dokumen480 halamanHCS AuditLogReferenceGuide hc2132scribd_728Belum ada peringkat

- Baidu SSD PDFDokumen14 halamanBaidu SSD PDFscribd_728Belum ada peringkat

- How Trespassing Works Using ALUA (Failover Mode 4) On A VNXDokumen2 halamanHow Trespassing Works Using ALUA (Failover Mode 4) On A VNXscribd_728Belum ada peringkat

- Configure SNMPv2/v3 for Solarwinds MonitoringDokumen7 halamanConfigure SNMPv2/v3 for Solarwinds Monitoring2629326Belum ada peringkat

- EEE TCS Accenture QuestionsDokumen2 halamanEEE TCS Accenture Questionsscribd_728Belum ada peringkat

- Canadian Entrepreneurship & Small Business Management: Balderson and MombourquetteDokumen23 halamanCanadian Entrepreneurship & Small Business Management: Balderson and MombourquettePrerna AroraBelum ada peringkat

- Debate ScriptDokumen8 halamanDebate ScriptAnn PhungBelum ada peringkat

- Critical Theory: Marxist CriticismDokumen51 halamanCritical Theory: Marxist CriticismAiryn Araojo LoyolaBelum ada peringkat

- The Social Pillar: Investing in The People of KenyaDokumen44 halamanThe Social Pillar: Investing in The People of KenyaJerusha Kimani KoskeyBelum ada peringkat

- Emerson Rosaupan Calamity LoanDokumen3 halamanEmerson Rosaupan Calamity LoanErere RosaupanBelum ada peringkat

- Gap 4-6 PDFDokumen19 halamanGap 4-6 PDFShafiq RehmanBelum ada peringkat

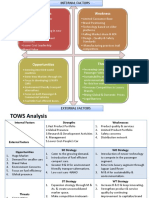

- Tata Motors SWOT TOWS CPM MatrixDokumen6 halamanTata Motors SWOT TOWS CPM MatrixTushar Ballabh50% (2)

- Parco Report (FINAL)Dokumen28 halamanParco Report (FINAL)haroonrashid00767% (3)

- Economics 11th Edition Michael Parkin Solutions Manual 1Dokumen29 halamanEconomics 11th Edition Michael Parkin Solutions Manual 1jackqueline100% (37)

- OB Group Assignment Group 7Dokumen9 halamanOB Group Assignment Group 7Rekik Solomon100% (3)

- 500 Banking Awarenes One LinerDokumen35 halaman500 Banking Awarenes One LinerLatta SakthyyBelum ada peringkat

- US Internal Revenue Service: 064602fDokumen6 halamanUS Internal Revenue Service: 064602fIRSBelum ada peringkat

- Start Making A Difference - How To Launch A Career in International Development PDFDokumen41 halamanStart Making A Difference - How To Launch A Career in International Development PDFAndry Yudha KusumahBelum ada peringkat

- Paper 5newDokumen625 halamanPaper 5newratikanta pradhan100% (1)

- Risk Management FrameworkDokumen32 halamanRisk Management FrameworkC.Ellena100% (1)

- Atkinson c08Dokumen27 halamanAtkinson c08mrlyBelum ada peringkat

- 10 Donors TaxDokumen39 halaman10 Donors TaxClaira LebrillaBelum ada peringkat

- Iimu Summer Placement Audited Report 2022 24 May 25Dokumen13 halamanIimu Summer Placement Audited Report 2022 24 May 25Mayank SukhaniBelum ada peringkat

- Don Eulogio de Guzman Memorial National High School: La Union Schools Division OfficeDokumen2 halamanDon Eulogio de Guzman Memorial National High School: La Union Schools Division OfficeMary Joy ColasitoBelum ada peringkat

- Tragakes Exam Practise Questions HL Paper 3Dokumen15 halamanTragakes Exam Practise Questions HL Paper 3api-260512563100% (1)

- Default notice promissory letterDokumen4 halamanDefault notice promissory letterAlyssa Pinar AñanaBelum ada peringkat

- Operations Management (TQM)Dokumen21 halamanOperations Management (TQM)2ndYEAR ARQUEROBelum ada peringkat

- Sec 34 Second Generation Data Quality SystemsDokumen20 halamanSec 34 Second Generation Data Quality Systemsapi-3699912Belum ada peringkat

- Amazon NordstormDokumen7 halamanAmazon NordstormyyyBelum ada peringkat

- What Is The Money MarketDokumen22 halamanWhat Is The Money MarketMuhammad HasnainBelum ada peringkat

- Pag-IBIG Data FormDokumen2 halamanPag-IBIG Data Formnelia_villarete3070Belum ada peringkat

- Investment Property and Cash Surrender ValueDokumen4 halamanInvestment Property and Cash Surrender ValueJoanne Jean Ibonia RosarioBelum ada peringkat

- Characteristics of Perfect CompetitionDokumen2 halamanCharacteristics of Perfect CompetitionJulie ann YbanezBelum ada peringkat

- The Rise and Fall of Phar-Mor Inc.Dokumen14 halamanThe Rise and Fall of Phar-Mor Inc.Louis Lebron100% (1)

- EEI Master Netting Agreement FaqDokumen3 halamanEEI Master Netting Agreement FaqOSRBelum ada peringkat