Exploring The Role of Leader Subordinate Interactions in The Construction of ORG Positivity

Diunggah oleh

tomor2Deskripsi Asli:

Judul Asli

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Exploring The Role of Leader Subordinate Interactions in The Construction of ORG Positivity

Diunggah oleh

tomor2Hak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Leadership

http://lea.sagepub.com Exploring the Role of LeaderSubordinate Interactions in the Construction of Organizational Positivity

Miguel Pina e Cunha, Rita Campos e Cunha and Armnio Rego Leadership 2009; 5; 81 DOI: 10.1177/1742715008098311 The online version of this article can be found at: http://lea.sagepub.com/cgi/content/abstract/5/1/81

Published by:

http://www.sagepublications.com

Additional services and information for Leadership can be found at: Email Alerts: http://lea.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Subscriptions: http://lea.sagepub.com/subscriptions Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Permissions: http://www.sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav Citations http://lea.sagepub.com/cgi/content/refs/5/1/81

Downloaded from http://lea.sagepub.com by Tomislav Bunjevac on May 4, 2009

Leadership

Exploring the Role of LeaderSubordinate Interactions in the Construction of Organizational Positivity

Miguel Pina e Cunha, Rita Campos e Cunha and Armnio Rego, Faculdade de Economia, Universidade Nova de Lisbon, Portugal and University of Aveiro, Portugal

Abstract In this article we discuss individual implicit theories of how positive and negative organizing unfold. The discussion is grounded in data collected from 89 individuals working in different organizational contexts. An inductive logic was followed, based on critical incidents of positive and negative processes and outcomes presented by participants, according to how they viewed their professional situation. Through a dialectical process of analysis, we extracted six dimensions that were present in different combinations among narratives provided by the participants: recognition/indifference, communication/silence, interaction/separation, condence/ distrust, loyalty/betrayal, and organizational transparency/organizational secrecy. We then analysed how these dimensions t together and discovered that they could be organized around four major patterns combining the clarity/secrecy of organizational rules and the considerate/detached behavior of leaders. We assert that positive leaders are essential in the creation of patterns of organizing, regardless of the features of the external context. Keywords leadership; organizational energy; positive organizing

Introduction

The notion of positive organizations has made a triumphant arrival on the scene of organization studies in very recent years (Cameron et al., 2003; Luthans, 2002; Luthans & Youssef, 2007; Nelson & Cooper, 2007; Spreitzer, 2006). Positive oriented researchers have focused on topics as unusual in the organizational literature as happiness (Wright, 2004), hope (Ludema et al., 1997), humility (Vera & RodriguezLopes, 2004), resilience (Sutcliffe & Vogus, 2003), positive deviance (Spreitzer & Sonenshein, 2004), compassion (Kanov et al., 2004), forgiveness (Cameron, 2007) and virtuosity (Gavin & Mason, 2004), to mention just a few. Accepting the challenge of positive psychologists such as Seligman and Csikszentmihalyi (2000), positive organizational scholars have suggested that the bias toward the negative (stress, work overload, worklife imbalance, unethical behaviour) should be counterbalanced with more attention to the virtuous side of organizing. With the present

Copyright 2009 SAGE Publications (Los Angeles, London, New Delhi, Singapore and Washington DC) Vol 5(1): 81101 DOI: 10.1177/1742715008098311 http://lea.sagepub.com

Downloaded from http://lea.sagepub.com by Tomislav Bunjevac on May 4, 2009

Leadership

5(1) Articles

work, we contribute to the eld of positive organization studies by discussing how the dynamics of positivity (and by contrast, negativity) unfold in organizational contexts. An inductive approach is applied to data collected from a sample of 89 individuals working in different jobs and organizations. We start with a brief and general introduction to positive organization studies.

What is positive organizing?

Organizations are often approached from a negative perspective, in both the theoretical and applied domains, as demonstrated by the imbalance between negative and positive papers published in the organizational behaviour and management literature (Luthans, 2002). Theories have been developed to explain how to manage stress and burnout, how to prevent bullying, how to deal with organizational cynicism and how to energize unmotivated people. Worklife imbalance, organizational misbehaviour, the consequences of massive layoffs and the breach of psychological contracts have also attained important places in the research agendas. On the contrary, the positive virtues and strengths of individuals and organizations have been taken as soft topics with minor relevance in the hypercompetitive world of organizations. Even in more applied domains, such as consulting, the negative model tends to prevail: companies are diagnosed according to a logic of disease and consultants mimic physicians with their prescriptions to cure the organization. Recently, however, important changes have been witnessed in the corporate as well as the academic landscapes. The eruption of corporate scandals in some of the worlds leading companies, the September 11th tragedy and the interest in topics such as positive psychology, positive organizational scholarship and appreciative inquiry, have contributed to the creation of a momentum for a positive approach to work and organization. Positive theories have ourished and positive forms of intervention have received increased attention, from both academic and popular authors. Interestingly, attention to both good and evil have characterized organizational research. Some authors have devoted attention to the dark side of organizational behavior (Grifn & OLeary-Kelly, 2004) and the executive psychopaths and snakes in suits (Morse, 2004; Spinney, 2004), whereas others have focused on the analysis of healing leaders and ofce angels (Frost, 2003; Kuper, 2004). We are interested in the development, rather than the outcomes, of both positive and negative organizational contexts. We suspect, considering previous research, that the outcomes generated by positive individual and organizational processes may be favourable (Fulmer et al., 2003; Judge et al., 2001) but make no claims about them. It is plausible that positive and negative processes mirror each other, but investigating such a notion demands further empirical analysis. Despite the relevance of this contrast, we embrace the positive movement and strive to contribute to a better understanding of how positivity grows in organizations. Hence our preferential focus on positive theories and interventions, while keeping an eye on the the negative, in order to avoid it.

Positive theories

Positive theories have been developed at several levels of analysis. The virtues of positive individuals have been extolled and individual traits have been shown to produce favourable results. The traits that constitute a positive self-concept have been

82

Downloaded from http://lea.sagepub.com by Tomislav Bunjevac on May 4, 2009

Leadership

Exploring the Role of LeaderSubordinate Interactions Cunha et al.

found, in a meta-analytic study conducted by Judge et al. (2001), to signicantly and positively impact job satisfaction and job performance. Humility has been presented as a trait of those leaders who create great companies (Collins, 2001). At the group level, psychologically safe teams where interactions are more honest and genuine have been demonstrated to be more conducive to learning (Edmondson, 1999). They constitute the holding environments that promote rich interpersonal relationships. These, in turn, facilitate collective learning and interpersonal trust (Kahn, 2005). The role of authentic leaders has also been scrutinized and the positive impacts of authentic leaders on their teams have been studied (Luthans & Avolio, 2003). At the organizational level scholars have investigated, for example, truly healthy organizations (Kriger & Hanson, 1999), authentizotic organizations (Kets de Vries, 2001; Rego & Cunha, 2008), virtuous organizations (Gavin & Mason, 2004) and organizational virtuousness (Cameron et al., 2004). In other words, organizations roughly corresponding to the prole of the best companies to work for have been held up as an ideal to pursue, and as being more effective economically (Cameron et al., 2004; Fulmer et al., 2003) than a comparable sample of rms.

Positive interventions

Diagnostic and intervention approaches usually seek to locate sources of mist and to reestablish a state of t in the organizational system. The logic of diagnosis is employed by Weisbord (1976), for example, to identify the sources of problems or mist and to solve them. Taking organizational systems as congurations, researchers and practitioners try to identify those subsystems that, for some reason, are not aligned with the conguration. In other words, they apply a disease model to their interventions. The positive appreciative inquiry logic, however, springs from a different perspective. Instead of looking at the problems with the organization, it stresses the best of the organizational system (Powley et al., 2004). It suggests the need to develop an imaginative and progressive view of organizations, based on their positive qualities (Cooperrider & Srivastva, 1987). This positive approach is expected to reinforce what the organization is already good at, and to trigger a virtuous spiral. Given appreciative inquirers assumptions that we create the world we later discover, this positive look at organizations will presumably end up producing positive organizations. After this generic introduction, and given the inductive logic followed in this research, we describe the research rst and discover the theory thereafter. We basically seek to answer the question: where does positivity come from?

Method

To analyse the dynamics of positive organizing, data were collected from 89 participants through snowballing. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with a diversity of people in different professions. The conversations were taped and transcribed in order to facilitate interpretation. Of the participants, 47 were male. Their ages ranged from 24 to 61, with a mean age of 34. They worked in a variety of organizations and industries (e.g. computers, banking, telecommunications, consulting, oil, central administration), holding a diversity of jobs (manager, controller, consultant, social worker, scientic director, director of human resources). They all conducted their professional activity in Portugal. Table 1 presents the characteristics of the sample.

Downloaded from http://lea.sagepub.com by Tomislav Bunjevac on May 4, 2009

83

Leadership

5(1) Articles Table 1 Description of participants

Participant 1 Age 26 Sex M Profession Manager Representative quote When they tell me that I have not reached the goals and when actually I was not informed about any goals, the question is . . . what exactly did I fail to achieve? It is you, with your initiative that build opportunities. We agreed a salary and thats what they pay me. They also promised me a portable computer, but Im still waiting for it. We have the civil sector career logic. I cannot change to the technical career. No surprises! Everything is very well dened . . . we all know the rules. There is a lack of balance between benets and responsibilities. People here do not put their hands in the re for you. There are no clear criteria for promotions . . . it depends if you are a yes man. . . . Threats are a constant. I always have the chance to give my opinion about things. There is no communication . . . we commit ourselves very much . . . we show up before our clients and then, nothing happens! This is all very unfair and demotivating. I always try to transmit the positive side of what we have to do. I would like my boss to give me spontaneous feedback. I have to constantly keep asking if everything is OK. The relationship with my supervisor is supercial: good morning, good afternoon, business issues. Recognition. More often than not it is all about recognition. Yes, Im happy. They are doing what theyve promised. I feel recognized by the organization. As being part of a family. He [the supervisor] is a very ambitious person. We were about 40 . . . when the third person left, everybody realized that something strange was going on. I feel, from the organizations hierarchy, that Im treated like a human being. He [the supervisor] talks to me through the others. There is a major concern with people . . . good working environment, interesting projects. We have an environment of trust, friendship and mutual esteem. It is difcult to improve anything, when your Director does not help you. On the weekend, I feel as Im on the clouds, but Sunday afternoon, I start feeling anxious. A supervisor must have the same criteria to be fair, whether it is good or bad for me. Theyve put me between a rock and a hard place: I should give up my studies to keep my job. It was something like a shock!

Continued

2 3

27 35

M F

Manager Journalist

4 5 6 7 8

49 39 31 32 29

F F M M M

Civil Servant Consultant MNC Business Unit Director Senior Consultant Salesperson, Pharmaceutical MNC Audiovisual Operator Superior Technician, Civil Servant

9 10

36 32

M F

11 12

54 29

F F

Manager Project Manager

13 14 15 16 17 18

45 28 30 27 24 42

F M M F F M

Accountant CRM Consultant IT Consultant Bank-branch employee Events Manager Manager, Consulting Firm Sales Director, Auto-company IT Technician Consultant Ballet Dancer Chemical Engineer Scientic Manager, MNC Pharmaceutical Physician Customer Support Technician, MNC IT

19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26

30 27 27 38 42 35 32 27

F F F F M F F M

84

Downloaded from http://lea.sagepub.com by Tomislav Bunjevac on May 4, 2009

Leadership

Exploring the Role of LeaderSubordinate Interactions Cunha et al. Table 1 (Continued)

Participant 27 Age 30 Sex M Profession Logistics Technician, MNC IT Project Manager Software Developer Representative quote Being recognized for my effort to help a customer led me to consider that it is better to trust people, rather than keeping a defensive attitude. If they [the results of performance evaluation] were published, that would create a lot of conicts. I know that sometimes I do a good job, others a bad one, and I recognize that I have been evaluated accordingly. I feel that Im treated with dignity and respect, that I am not just another one. He [supervisor] is rude, technically incompetent and personally unstable. It is impossible to enjoy working with him. The company does not motivate, does not give opportunities. . . . If the boss does not like you, you dont have a chance. I am fully satised. But I want more! Some people, with good connections, are beneted. I do not feel a lack of justice because Im doing nothing special: only my job. I think that what is missing is leadership. Leadership by a complete professional. Some people are not competent in some professional skills, such as interpersonal skills. Our credo is work can be fun! They have changed my ofce to a much worse place. I dont know why . . . we have no goals. I have two supervisors. Their behaviors are completely different. They are not an example. I have no doubt that this organization does not treat people the way it should. But sometimes your supervisor does. I was forced to align my thinking with him [the supervisor]. There is a constant concern with the satisfaction and preferences of workers. I got pregnant after six months in the company and I never heard any comments about it. The needs of the company are the only thing that counts. We are informed in due time about relevant decisions and changes. The way I was recruited was very impersonal. I should have noticed that. I was attracted by the organization, clarity and planning showed by this company. My supervisor is very direct. Sometimes some feedback may make you feel uncomfortable, but there is transparency though. I realized that some things that my Director told me were not really true. There are some general goals. They told me they wanted me to do this and that. They are realistic but require hard work. The management, after a merger with my company, clearly preferred the team from the company they came from.

Continued

28 29

33 30

F M

30 31

34 27

M M

Lawyer Quality Consultant

32

49

Middle Management, Central Administration High School Teacher Systems Analyst Systems Quality Technician Dental Health Technician Psychologist Manager Designer Accountant Manager

33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41

45 31 24 42 31 30 55 26 26

F F F M F M M F M

42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49

26 26 29 33 27 30 29 30

M F F F F M F F

Investment Banking Employee Bank Marketing Employee HR Technician Media Planner Controller Quality Department Coordinator Marketing Manager IT Technician

50 51

34 31

F M

Sustainable Development Manager Planning & Control Manager Chemical Engineer

52

30

Downloaded from http://lea.sagepub.com by Tomislav Bunjevac on May 4, 2009

85

Leadership

5(1) Articles Table 1 (Continued)

Participant 53 Age 30 Sex M Profession Computer Engineer Representative quote I remember my boss protected me. Well, not exactly protected me, but defended me in front of the marketing people. There is dialogue, we discuss things. Once, they listened to me. Now, it is only between them. There is no discrimination here. My predecessor in this job had a lighter workload and one person to help. It is important to feel that your commitment is rewarded. My new boss is harsh, rude, tends to disrespect people. Shes a bulldozer! I have many reasons to complain, since the geeographic separation. Im in Oporto and my supervisor in Lisbon. Dialogue is far from uid. Im ignored up there. Things often come dened from the top. . . . His role often consists in executing his orders. Every rule is clear. There are on-line documents, with warnings when things are not being done within the deadlines. Sincerity, in organizations? It is something that must be used in the right measure. Our supervisor rarely leaves her ofce to see how we are doing. Opportunities are well-publicized so that people may apply. He (the supervisor) rapidly discovered a favorite within the group I still give priority, the right of option, so to speak, to this company. If they assess us or not, I dont know. They say nothing about it. . . . Its all a mystery. People appreciate well-dened leadership. With clear ideas. Board members have consideration for my opinion. What they do to others, they may also do to you. So, its better to be careful. My supervisor is a great coach . . . fair, communicates very well, is very transparent, quite a role model! It was much like speaking to a wall . . . she blames me for her mistakes. There is no fair play, it is an open competition.

54 55 56 57 58 59 60

32 56 27 29 55 41 30

M F F F F M M

Inspector, Central Administration Management Assistant Finance Controller Project Manager Operations Manager Operations Director Sales Representative

61 62

30 43

M M

Controller Sales Director

63 64 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 72

35 33 36 28 29 61 31 30 29 27

M F F M M F F F M F

Sales Representative Nurse Nurse Financial Analyst IT Technician Social Services Worker Auditor Management Assistant Auditor Marketing Analyst, MNC Sales Representative, Pharmaceutical MNC Product Manager, Pharmaceutical Company University Researcher

73 74

27 36

M F

75

25

76 77

27 57

M F

Consultant Manager, State-owned Organization

I was really angry. I told who needed to be told. But among us there is no . . . I think each of us has his/ her work to do and thats all. I think that the whole context is highly stimulating. They spend a whole day listening to our input. But in the end, they have not accepted even a single suggestion.

Continued

86

Downloaded from http://lea.sagepub.com by Tomislav Bunjevac on May 4, 2009

Leadership

Exploring the Role of LeaderSubordinate Interactions Cunha et al. Table 1 (Continued)

Participant 78 Age 44 Sex M Profession Salesman Representative quote Yes, I trust the company. It is a stable company with a future, whose decisions take worker well-being into account. What is missing is dialogue, clear procedures. Job satisfaction is as low as possible. In contrast, the rms communication machine, or better, propaganda machine . . . works. It works so well that the company has been considered as one of the nations best companies to work for. This is the profession I chose. . . . Yes, yes, yes, I am a motivated person. There is a big annual survey aiming to collect peoples assessment of the rm. My supervisor often takes rabbits out of the hat. Its better to keep your mouth shut. You never know what his [supervisor] reaction will be. Im not saying that it is paradise, but the concern with people is genuine. We have a great proximity, we invade each others ofce. When I give my opinion, it tends not to be appreciated, in comparison with other peoples opinions. At the company they did not accept it [a debilitating disease] and didnt approve my visits to the doctor. His nomination was a big shock for me.

79 80

43 32

M M

Middle Management Consultant

81 82 83 84 85 86 87

50 27 30 46 40 28 26

M M M M M M M

Hospital Manager Consultant Engineer, Utility Engineer Consultant HR Manager, Banking Assistant to the Board, Private Hospital Financial Analyst

88 89

36 34

F M

Entrepreneur Engineer

The semi-structured interviews followed a predetermined but loose structure. The interviewing philosophy was, following Alvessons (2002) terminology, more romantic than neopositivist. In other words, we were looking for lived experience and deep meaning rather than for context-free truth. After a brief biographical sketch, participants were invited to think about their professional experience, to classify it as, generally speaking, positive or negative, and then to explain why, using a critical incident to illustrate their evaluation. With this critical incident approach we sought to understand the antecedents and the process leading to situations that people would qualify as positive or negative. We believe that the selection of critical incidents elicits events that are important to those who lived them. As such, our ndings are based on episodes having a major impact on peoples view of the paths to positivity/negativity. The retrieval of signicant events led to signs of emotionality, especially during the conversations on negative events. In some cases, people expressed the anger they were feeling toward the agent that triggered the negative dynamic and as we will discuss below their supervisor tended to prevail in this regard. A few people even said that they were only then realizing how unfair the situation was, even when it took place some time ago. As the incidents were being collected, the same stories were repeated over and over, and new information was not being reported to challenge the stability of the interpretation (Glaser & Strauss, 1967). Major sources for guiding data analysis included Flanagan (1954), Glaser and Strauss (1967), Mintzberg (1979), Roos (2002)

Downloaded from http://lea.sagepub.com by Tomislav Bunjevac on May 4, 2009

87

Leadership

5(1) Articles

and Alvesson and Deetz (2000). The procedure consisted of three major phases: (1) eliciting critical incidents on the dynamics of organizing; (2) comparing between theory and data until the adequate conceptual categories stabilized; and (3) deriving patterns associating the categories discovered in the previous phase. In analysing the transcribed interviews, we used a dialectical process (Weston et al., 2001), that is a recursive, iterative process in separating the conceptual categories from the critical incidents. The rst author developed an initial list of categories, which was then sent to the other two researchers. After revisiting the transcripts, we met to discuss the initial list of categories and, through consensus, some categories were dismissed and new categories were proposed, as well as interactions between them. The rst author used this new list to make another review of the transcripts and identify ner meanings and evidence to support or challenge the suggested categories. This revised list was fed back to the other researchers, followed by group discussion. The process was repeated until we felt condent that the set of categories, which by now had four meta-categories and six pairs of inherent dimensions, as well as relational patterns amongst them, had stabilized and this collective process of social construction was mature enough to lead to a sufciently comprehensive understanding of the dynamics of positive organizing. To improve the adequacy of our argument, several additional measures were taken. We used triangulation by collecting data from a very diverse sample, in terms of age, gender, economic sector, organization and type of job. Moreover, some participants were able and willing to read the rst draft of the paper and comment on or question the meaningfulness of our interpretation. Furthermore, the research was presented in workshops and executive education sessions. The interpretation was considered acceptable in these various feedback exercises. In the following section, we discuss the two major phases of the data analysis: Step 1: the extraction of conceptual categories from the critical incidents. Step 2: grounded theorizing for combining the themes extracted in Step 1, into patterns able to uncover the more salient explanations.

Results and discussion

We start this section with a presentation of the themes that emerged as the more salient and stable ones from the interviews.

Step 1: critical themes

Six themes emerged that captured the essence of most of the episodes positive and negative revealed by our subjects. Interestingly, they can be understood as pairs, with one of the elements typically appearing in positive elements, and the other in the negative ones. These conceptual pairs are, in no special order, recognition/ indifference, communication/silence, interaction/separation, condence/distrust, loyalty/betrayal and organizational transparency/organizational secrecy. Despite the variation in the stories we heard, some of the following elements were present in many episodes. As such, we interpreted this nding as an indication that they play a signicant role in how the paths to positivity and negativity progress.

88

Downloaded from http://lea.sagepub.com by Tomislav Bunjevac on May 4, 2009

Leadership

Exploring the Role of LeaderSubordinate Interactions Cunha et al.

Recognition/indifference This dimension refers to the feeling of being recognized as making a contribution to the organization versus the lack of interest of the supervisor toward what people viewed as a contribution. Recognition, both emotional and intellectual, has been indicated as associated with organizational justice and fair process (Kim & Mauborgne, 1998). When people feel that the organization does not provide the adequate recognition, they express some form of psychological suffering. The following quote is illustrative: I have worked hard, really hard, sometimes I didnt even have the time to have lunch or to take care of the family. . . . I feel Ive been used. My heart is bleeding (Participant number 57, or P57). Recognition, on the contrary, stimulates positive feelings: I feel from the hierarchy that Im treated as a human being, that what I do is appreciated. It all starts in the top managers themselves. They transmit in a very informal, yet very explicit way, the recognition for the effort people put in their work (P70). Communication/silence This dimension refers to how the supervisor communicates with people. Some supervisors use honest communication and provide valuable information and feedback, whereas others keep the group in a state of ignorance regarding relevant issues (e.g. the employees performance assessment). Communication is sometimes used constructively. As reported by a 27-year-old consultant in a large multinational consulting rm (P21), when feedback is based on rigorous facts, not on impressions, and when negative feedback is provided with constructive intentions (e.g. accompanied by coaching and support), people feel that the company really cares about them. The reason why clear and honest communication is valued has to do with the fact that it signals care, authenticity and transparency, limits competition and disputes inside the organization and fosters psychological safety (Brown & Leigh, 1996). In these situations, as a participant pointed out, people dont have to adopt defensive tactics. When silence prevails, people feel confused and lost: I have many reasons to complain, since the geographic separation. Im here and my supervisor 300km away. Dialogue is far from uid. Im ignored up there (P60). Interaction/separation This theme refers to the quality of the interpersonal relationships and describes the extent to which a leader is accessible and interacts frequently with team members. Some leaders are viewed as accessible, others as detached and isolated. Interaction with the supervisor translates organizational rules into daily practices. Good interactions buffer people from bad policies. Bad interactions amplify bad rules and neutralize the advantages of good ones (Cameron, et al., 2004); and small causes may turn into big consequences (Plowman et al., 2007). Consider, for example, the following case: My supervisor does not act like a leader. Recently, he sent an email to every salesperson saying that we are paid to sell and that if we do not sell, we will suffer the consequences. There are many ways to say this very same thing. He could have sent the same message with a positive tone. That way, the message would have a positive effect, it would have energized us, it would signal that he

Downloaded from http://lea.sagepub.com by Tomislav Bunjevac on May 4, 2009

89

Leadership

5(1) Articles

was on our side. Given the way he put things, we could only think that he was going to re us the next month. (P73) If sometimes managers actively produce negative results, on other occasions they do the same passively. This may occur when people approach managers looking for help and do not receive it something that tends to damage the relationship between supervisor and subordinate (Cunha, 2002). The same sales representative mentioned above described a conversation with his supervisor as speaking to a wall (P73). The most positive situations in terms of learning and feeling respected occur when results are not satisfactory but the treatment is perceived as fair and respectful. On the contrary, anger was triggered by unfair treatment and offences from above, a nding that supports the results of Fitness (2000) and the evidence about organizational justice (Colquitt et al., 2001; Cropanzano & Greenberg, 1997; Weiss et al., 1999). As a consequence, some companies slide into contexts that limit the commitment between people and their organizations. Condence/distrust This dimension describes the emotional atmosphere experienced during the process leading to the episode. Feelings of condence or ow contrasted with climates of distrust, fear and oppression. Repression works, said a 30-year-old controller in a construction company (P61). Invited to explain the meaning of repression he mentioned a constellation of factors such as the lack of clear goals, decit of communication with the supervisor, lack of clear criteria for evaluation, and the supervisors style, characterized as old school type. As a result, he reports situations such as the difculty in uncovering errors (If we were not afraid of repression, errors could be seen as a stimulus, we would report them easily and condently) and the discretionary use of power, namely in terms of performance assessment, where the momentary sensitivity of the supervisor plays a signicant role. Similar remarks about what an interviewee described as bulldozer-style leadership were cited (P59). The style often results, as a principal in a professional services company pointed out, in aggressive organizational climates: We are always waiting to be attacked (P84). The scientic director of a pharmaceutical rm said that her supervisor was so threatening that every Sunday afternoon she started to feel the anxiety (P24). As a consequence of this leadership behaviour, as one participant put it, I always try to protect myself from being beaten (P84). Other examples of leadership by fear suggest that some leader behaviours actually direct teams onto a negative path: He is not polite, is technically incompetent and lacks emotional intelligence. He is very insecure and is always defending himself. Sometimes he deceives people. For example, he appropriates other peoples merits. In that sense, he is dishonest (P31). Other subjects report their dissatisfaction with the lack of coaching and support from supervisors: They are only concerned with prots and the bottom line. Nothing else matters. They dont care about the quality of work, if things are well done or not. Technical support is zero (P12). These effects are in stark contrast with the consequences of condence: I have been treated fairly when I did something wrong. These situations have a special impact because they are the most valuable from a learning perspective (P29).

90

Downloaded from http://lea.sagepub.com by Tomislav Bunjevac on May 4, 2009

Leadership

Exploring the Role of LeaderSubordinate Interactions Cunha et al.

Loyalty/betrayal Two contrary types of attachment with the organization emerged: loyalty and betrayal. An interesting aspect of this dimension resides in the fact that the sense of loyalty or betrayal is often expressed toward the organization but is stimulated by the leaders role. Thus, feelings toward the leader may spill over to the organization. A consultant felt betrayed when his former supervisor left the rm to launch a new business with some of his former subordinates. This consultant was left behind. He later pointed out that, It was not being left behind. It was the lack of honesty. He [the supervisor] left and then people started to leave, one after the other (P18). He claims that the supervisor developed a sense of family within his team, and that the family was destroyed by the same person who created it. Another example: when the participant asked his supervisors permission to study management in a university programme at the end of the day, he met with strong resistance. He was surprised because the opportunity had been discussed before and approval was promised. This new attitude was perceived as a broken promise, a disruption of expectations, as evidence that the supervisor should not be trusted. Organizational cynicism, resulting from the perception that managers should not be trusted (Dean et al., 1998) also erupted as a result of the perception that the rules of the organization had been changed while people were playing the game. A consultant for a multinational professional services rm felt that the organizational climate in the company was negative because a new career system had been implemented. The system held back career movements and was perceived, again, as a broken promise (people worked hard because they expected rapid advancement). Additionally, people knew what to expect. After the new system was implemented, they did not: job satisfaction is as low as possible. In contrast, the rms communication machine, or better, propaganda machine . . . works. It works so well that the company has been considered as one of the nations best companies to work for (P80). In contrast, organizations may build good intentions and feelings of loyalty In my rst year in the company I was invited on the annual trip to Brazil, that year. . . . At the time, I did not deserve that prize, but the fact is that the company conquered me at that very moment. This feeling has lasted until today (P2). Organizational transparency/organizational secrecy This refers to the clarity of the organizations rules and polices. In some cases they were viewed as clear, whereas in others they were taken as obscure: everything is a mystery. We are simply not informed (P68), and she adds: everything could change with open communication. Presently, people are afraid to talk. Secrets and mysteries are also mentioned with regard to performance management. As an engineer in a utilities rm observed, the assessment process is merely theatrical and the result is dependent on the supervisors criteria (P83). As the process at the company level is viewed as merely bureaucratic, supervisors have a great deal of discretion. They do not have to justify their decisions and, as the same person remarked, sometimes they pull some rabbits out of the magic hat, meaning that they have access to information that no one else has and that this information can be used at will: when they tell me that I have not reached the goals and when actually I was not informed about any goals, the question is... what exactly did I fail to achieve? (P1).

Downloaded from http://lea.sagepub.com by Tomislav Bunjevac on May 4, 2009

91

Leadership

5(1) Articles

A man in a hygiene products company, who felt unfairly treated, said that the information he had access to was broadcast via the so-called Radio Corridor (P79). As a result, he informed his supervisor six years ago that he felt his salary should be increased. As a response he was told that the companys door is really big . . .. From that moment on he did not raise the issue again. He added that the above situation showed him that the company considered that my value is zero. When questioned about how he dealt with this, the answer was, I just dont care. The literature suggests that positive organizing thrives on clarity (Cohen and Prusak, 2001), not on mystery, as seems to be the case with the situations mentioned by these interviewees. Another consequence of the lack of clarity is the increase in organizational politicking. A product manager in a pharmaceutical company described how political games thrived in the absence of transparency: there is a lot of politics. Relationships are informal but not transparent. The atmosphere is really bad. But on the surface we have . . . la vie en rose. Everybody invites everybody for a coffee (P75). In other cases, the organization created clear rules and enforced their application. When these rules were perceived as aimed at benetting the employees, their effect could be especially positive: we have long and demanding work days. To reward our effort, the company gives us some extra days off. These days, once dened, cannot be changed. That is very important because in this business there is a lot of pressure to respect deadlines and therefore there is some tendency to align private life with the companys interest (P14).

Step 2: Patterns

Having described the major themes in our data, we next present the relational patterns amongst them. As stated in the method section, the iterative process we used to analyse the transcripts of the critical incidents, in which we collectively sought to nd the underlying dynamics of positive organizing, led us to the identication of pairs of dimensions associated with the six categories, as well as to the relational patterns amongst them. These patterns are not dissociated from the dimensions, but for clarity purposes, we must describe them separately. Four distinct relational patterns emerged, two leading to positivity and the other two to negativity. It is important to observe that the previous conceptual themes organize in a stable way: the themes mentioned by an interviewee tended to be strongly associated in terms of their sign. For example, recognition tended to be coupled with condence or loyalty, but not with fear or feelings of betrayal. In the same vein, indifference was associated with fear or betrayal but not with condence or loyalty. Organizational transparency or secrecy was not subjected to the same kind of relationship found in the other conceptual themes. In other words, more or less, transparency was not necessarily associated with positive or negative incidents. This allows us to consider that, broadly speaking, there is one organizational category (organizational transparency or secrecy) and ve leadership-related categories (Table 2) that reect a detached or a considerate style of leadership. The two main factors (leadership and organizational rules) can then be taken as independent, but the concepts composing each of these factors are interdependent (i.e. condence tends to appear together with loyalty, but not with isolation). We

92

Downloaded from http://lea.sagepub.com by Tomislav Bunjevac on May 4, 2009

Leadership

Exploring the Role of LeaderSubordinate Interactions Cunha et al. Table 2 Leadership behaviours and organizational rules: the two factors leading to positivity/negativity

Leadership Considerate Recognition Communication Interaction Condence Loyalty Detached Indifference Silence Isolation Distrust Betrayal Organizational rules Clear Organizational Transparency Secret Organizational Secrecy

continue the discussions with the presentation of the four patterns that were identied, which were the following: Path 1: clear rules + considerate leader positive organizing Path 2: clear rules + detached leader negative organizing Path 3: secretive rules + considerate leader positive organizing Path 4: secretive rules + detached leader negative organizing Path 1: clear rules + considerate leader positive organizing The situation identied as the most favourable by the participants was the one involving considerate leaders acting with clear and fair organizational rules. This pattern was characterized by the presence of most of the positive categories identied above: individual recognition, honest communication, easy interaction, condence, a sense of loyalty and clear rules. This dynamic has similarities with the contexts described by Lawler (2003) as virtuous spirals: considerate leaders apply a set of clear rules leading to a cycle where people feel energized, involved and sometimes in a state of ow, thus fostering organizational health (Quick & Macik-Frey, 2007) and collective thriving (Spreitzer & Sutcliffe, 2007). This was described by our interviewees as the situation that best utilized their skills and talents. This virtuous combination corresponds to what may be best described as positive organizing. People felt engaged by a common goal, the leader was viewed as a facilitator, politicking was not a major issue, and personal defenses were dormant. In other words, considerate leaders and clear rules create energetic and intensely positive environments. Path 2: clear rules + detached leader negative organizing A second path, associated with negativity, was characterized by the combination of clear rules and a detached leader. Despite the existence of clear organizational rules, people did not show such feelings as condence, loyalty and so forth. Relationships with the leader were distant and defensive. The result of this dynamic was perceived by people as frustrating and negative. Employees did not express a highly intense negative emotion but a mild negativity. This state can be interpreted according to the theories of organizational justice (Colquitt et al., 2001): rule clarity guaranteed a reasonable degree of procedural fairness, but the detached behaviour of the leader produced feelings of injustice due to the lack of interactional fairness.

Downloaded from http://lea.sagepub.com by Tomislav Bunjevac on May 4, 2009

93

Leadership

5(1) Articles

Path 3: secretive rules + considerate leader positive organizing The third path we identied was characterized by a combination of unclear, secretive organizational rules and a considerate leader. It mirrors the previous path: despite the lack of an adequate context, the leader does what he or she can to produce a positive organizational setting. Given the difculties of such a task, people tended to express appreciation toward the leader and the situation was labelled by interviewees as positive (P61). When this description was provided, people did not express a great enthusiasm toward the organization; hence, the energetic levels were low but, within the group, feelings of recognition, honest communication, easy interaction, condence and loyalty were expressed. People viewed the leader as a buffer, someone who defended the group against external adversity (Gabriel, 1999; see also quote of P5 in Table 1) and who provided adequate and fair explanations (Cropanzano & Greenberg, 1997). This created a positive attitude toward the leader and a sense of belonging to a team that prevailed over the secrecy of the rules and the context provided by the organization, which is congruent with data suggesting that interactional justice can reduce the negative impact of procedural injustice (Skarlicki and Folger, 1997). This pattern, and the previous one, reveal the role of leaders in the construction of positive organizations. Considerate leaders protect the group from a negative context, whereas detached leaders neutralize the positive context around them. Leaders, in this sense, may play a particularly important role in their subordinates construction of the positive organization. Given the ambiguity and symbolism associated with leadership (Pfeffer, 1977), peoples perceptions of positive or negative organizing may be a consequence of their interpretation of leader behaviour. Hence, the associations between good leaders/positive organizations and bad leaders/negative organizations. Path 4: secretive rules + detached leader negative organizing This is the situation that elicited negative emotionality during the interviews. Peoples stories and ex post reactions evoked the notion of destructive emotions produced by toxic leaders (Frost, 2003). When subjects felt that the situation was tainted with generalized injustice, their feelings were the most negative and, in some cases, surfaced during the interviews. There was, they said, no reason to express any kind of gratitude toward the organization or the leader. Secrecy was practiced by the immediate leader and dominated the organization. People expressed anger and, as mentioned above, sometimes the dormant feelings were clearly evident when the episode was narrated. The consequences of negativity have been explored by other authors: much employee disengagement and lack of performance results from feeling cheated, of feeling they have not been actively involved and consulted in decisions, such as those relating to benets, that they believe are crucial to them (Gratton, 2004: 23). Lack of participation and the feeling of being cheated were the source of negative attitudes and emotions and constituted an inevitable path to negativity. These four patterns resonate Bruch and Ghoshals (2003) description of the several forms of organizational energy. Clear rules and considerate leaders tend to focus peoples attention on goals. This may facilitate the creation of a productive or passionate organization. Clear rules and detached leaders may create a feeling of resignation, characterized by low intensity negative energy, at least in collectivist and

94

Downloaded from http://lea.sagepub.com by Tomislav Bunjevac on May 4, 2009

Leadership

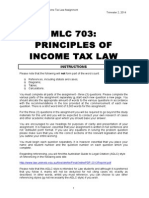

Exploring the Role of LeaderSubordinate Interactions Cunha et al. Figure 1 The Z path to positive organizing

Detached

Leadership

Considerate + ++

Opaque Organizational Rules

Clear

high-power distance cultures, such as the one in which this study was conducted, in which obeying a paternalistic leader may be more crucial than following specic procedures (McFarlin & Sweeney, 2001: 86). Secretive rules and considerate leaders may create a comfort zone: people feel protected but are not enthusiastic about the organization. Secretive rules and detached leaders create aggressive organizational climates, marked by high-intensity negative energy. If our interpretation is correct, organizational energy results from the way in which individuals read the organizational context, and particularly a highly salient element in that context: their immediate leader. Positive leaders are the agents of virtuous organizing. As depicted in Figure 1, the path from more negative to more positive zones can be a result of an increase in the levels of leadership consideration and organizational clarity. Their impact, however, may be leveraged or inhibited by the context surrounding the team, namely organizational policies and their impacts on feelings of justice or injustice.

Conclusion

Some organizations establish relationships with their members that are so negative that negativity can spread within the company even to non-work-related events. For example, one of our subjects attributed the dissolution of his marriage to the company: we worked so hard! Some days I almost didnt go home. Result: my marriage failed and my life lost its meaning (P23). Other companies, on the contrary, add meaning to the life of their members. According to our ndings, a major inuence on the development of a positive or negative process is leader behaviour. This is in line with research showing that the immediate supervisor is the major stimulus for positive or negative action (e.g., Bateman & Organ, 1983; Cardona, 2000; Moorman, 1991). Farh et al. (1990) also stressed that the supervisor has a determining or mediating role in many of the returns to the subordinate. He or she enacts both

Downloaded from http://lea.sagepub.com by Tomislav Bunjevac on May 4, 2009

95

Leadership

5(1) Articles

formal and informal procedures or organized activities that inuence a persons sense of fairness in the social contract. Supervisors behaviours are the main indicator used by employees to evaluate how the organization treats and appreciates them. As Wong and Lui (2007) pointed out, employees leave managers, not organizations. Leader behaviour is able to buffer the team from secretive rules or to neutralize the positive effects of clear rules. When leaders express a reduced willingness to listen to their team members, they create a process that may be difcult to reverse. When questioned about how they deal with situations that they perceive as negative, people often offer some variation on the following quotation: have I discussed the situation with my boss? He is not the kind of person open enough to this sort of discussion, as reported by an engineer (P83). The supervisor is the translator of organizational policies and rules. The way these are appropriated by the leader and transmitted to the team help to make differences between positive and negative organizing. One person in our sample mentioned that, even aware that his supervisor was applying the rules received from headquarters in another country, he was puzzled by the acritical acceptance of those orders that, in his view, were not adequate to the countrys culture. In terms of practice, we offer two major conclusions: rst, that leader behaviour is crucial in the creation of positive organizational contexts with good leaders being able to neutralize an inappropriate organizational context; and, second, that productive organizations, in the sense of the high-intensity positively energized organizations described by Bruch and Ghoshal (2003), are more likely to exist when the considerate leaders that create positive contexts are supported by clear organizational policies and rules that facilitate the creation of perceptions of organizational justice and foster organizational health (Quick & Macik-Frey, 2007). Some organizational processes have traditionally been conducted in secretive ways. Aram and Walochik (1996), for example, explained how the lack of clarity of performance management systems allowed managers to use their power in a discretionary way. This article makes several contributions to the organizational literature. It helps to understand peoples implicit theories of positive and negative organizing. We also add to the literature on how leaders affect the feelings of their followers, a research stream that Brief and Weiss (2002) qualied as embryonic. We provide evidence consistent with the idea that the main internal problems in rms arise from a feeling of not being fairly treated and respected by the organization (Vera & RodriguezLopez, 2004). We noticed that the leaders behaviour proves to be crucial for the evaluation of the rm as a whole: leaders personify the rm. In this sense, considering the extraordinary nature of leaders as represented by followers (Gabriel, 1997), they have a signicant emotional impact on their followers even when they do not expect it. As expressed by Alvesson and Sveningsson (2003), their mundane behaviour is submitted to a process of extra-ordinarization; hence, their substantive emotional impact. We make no inferences regarding employee performance in any of the extracted paths. Some research suggests that positive dynamics facilitate better performance (e.g. Cameron, 2003; Quick & Macik-Frey, 2007; Spreitzer & Sutcliffe, 2007), but we do not take any sides on that issue. As such, it should not be inferred from our study that positivity paths are necessarily superior in terms of performance results. However, it does not diminish the relevance of the conclusions, in our perspective,

96

Downloaded from http://lea.sagepub.com by Tomislav Bunjevac on May 4, 2009

Leadership

Exploring the Role of LeaderSubordinate Interactions Cunha et al.

given the importance of human relations in the workplace. With this research, we also contribute to the emerging topic of organizational energy. We found an interesting parallel between the four patterns uncovered here and Bruch and Ghoshals (2003) work on psychological energy. The ndings also help to understand the sources of collective thriving (Spreitzer & Sutcliffe, 2007). Some characteristics of the study should be taken as potential limitations. The results we have obtained should be read with caution regarding generalization. Data were collected in a national culture characterized by strong afliation needs, high femininity and high power distance, which may have inuenced sensitivity to leader behaviour (Hofstede, 1980; Jesuino, 2002; McClelland, 1961). As such, the prominent impact of leader behaviour should be interpreted with care before attempts of generalization. Some authors suggest, for example, that organizational and leadership secretiveness may be more common in some national contexts than in others, a proposition worthy of further research (Li & Yeh, 2007). Despite this cautionary note, the importance of transparent interaction with others has been considered in distinct cultural settings (Avolio et al., 2004). Other limitations of the study are a consequence of the sample, which is biased toward people with qualied professions. The validity of these interpretations to different samples should not be taken for granted, and future work is necessary to test that possibility. A third limitation, associated with the method, refers to the fact that people presented ex post narratives of events. We may not assume that these are objective descriptions of the events; people tend to retrospectively justify their action in order to preserve order and self-esteem. Events may have been biased perhaps inadvertently, or not in that regard. Another possible limitation emerged as the study proceeded. As one of our anonymous reviewers noted, the way in which most interviewees approach the question was that they over-emphasised the negative behaviours they accounted for in their leaders; and he/she pointed out the irony that a piece of research into positivity might have drawn most of its data from interviewees experiences of negativity. This is an important observation, and one that conrms the potentially greater signicance of negative events, something that may be studied in further research. Further research may also consider the fact that in many of the responses, the interviewees apparently articulated an implicit parentchild model of the relationship between them and their leaders: repression, waiting to be attacked, they are only concerned with prot and the bottom line and protecting myself from being beaten. The nature of these conceptualizations of the relationship between leaders and subordinates may also deserve attention.1 In this project, we were looking for meaning (Alvesson & Deetz, 2000), and we found our meaning in the meaning provided by others. But, again, this does not rule out the possibility of alternative plausible explanations, nor the possibility that the acceptability of our explanations resulted from a process of social construction woven together amongst ourselves, the participants and the audiences with whom we shared the ideas. To wrap this point up, we do not assume the relationship between data and the outside world to be unproblematic (Alvesson & Skoldberg, 2000). With this in mind, we hope to have contributed to the emerging literature on positive leadership studies, namely on the buffering and amplifying effects of positive leader behaviour (Caza et al., 2004), as well as on the likely positive consequences of authentic (Avolio et al., 2004), ethical (Trevio & Brown, 2007) and transcendental leadership (Cardona, 2000). Our analysis of the interaction between leaders and their

Downloaded from http://lea.sagepub.com by Tomislav Bunjevac on May 4, 2009

97

Leadership

5(1) Articles

organizational contexts in the construction of positive (or, for that matter, negative) states of organizing is one step in the direction of the micro-processes facilitating the emergence and persistence of psychological capital.

Acknowledgements

We thank Joo Vieira da Cunha for his comments and suggestions. Miguel Cunha gratefully acknowledges support from Instituto Nova Forum. And we are grateful for the helpful comments and suggestions received from the Leadership team.

Note

1. We are grateful to a reviewer for this suggestion.

References

Alvesson, M. (2002) Postmodernism and Social Research. Buckingham: Open University Press. Alvesson, M., & Deetz, S. (2000) Doing Critical Management Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE. Alvesson, M., & Skoldberg, K. (2000) Reexive Methodology: New Vistas for Qualitative Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE. Alvesson, M., & Sveningsson, S. (2003) Managers doing leadership: The extra-ordinarization of the mundane, Human Relations 56: 143559. Aram, J. D., & Walochik, K. (1996) Improvisation and the Spanish Manager, International Studies of Management and Organization 26: 7389. Avolio, B. J., Gardner, W. L., Walumbwa, F. O., Luthans, F., & May, D. R. (2004) Unlocking the Mask: A Look at the Process by which Authentic Leaders Impact Follower Attitudes and Behaviors, Leadership Quarterly 15: 80123. Bateman, T. S., & Organ, D. W. (1983) Job Satisfaction and the Good Soldier: The Relationship Between Affect and Employee Citizenship, Academy of Management Journal 26: 58795. Brief, A. P., & Weiss, W. M. (2002) Organizational Behaviour: Affect in the Workplace, Annual Review of Psychology 53: 279307. Brown, S. P., & Leigh, T. W. (1996) A New Look at Psychological Climate and its Relationship to Job Involvement, Effort, and Performance, Journal of Applied Psychology 81(4): 35868. Bruch, H., & Ghoshal, S. (2003) Unleashing Organizational Energy, MIT Sloan Management Review Fall: 4551. Cameron, K. S. (2003) Organizational Virtuousness and Performance, in K. S. Cameron, J. E. Dutton, & R. E. Quinn (eds) Positive Organizational Scholarship, pp.4865. San Francisco, CA: Berrett Koehler. Cameron, K. S. (2007) Forgiveness in Organizations, in D. Nelson & C. Cooper (eds) Positive Organizational Behavior, pp. 12942. London: SAGE. Cameron, K. S., Bright, D., & Caza, A. (2004) Exploring the Relationships Between Organizational Virtuousness and Performance, The American Behavioral Scientist 47(6): 76690. Cameron, K. S., Dutton, J. E., & Quinn, R. E. (eds) (2003) Positive Organizational Scholarship. San Francisco, CA: Berrett Koehler.

98

Downloaded from http://lea.sagepub.com by Tomislav Bunjevac on May 4, 2009

Leadership

Exploring the Role of LeaderSubordinate Interactions Cunha et al. Cardona, P. (2000) Transcendental Leadership, Leadership and Organization Development Journal 21(4): 2017. Caza, A., Barker, B. A., & Cameron, K. S. (2004) Ethics and Ethos: The Buffering and Amplifying Affects of Ethical Behavior and Virtuousness, Journal of Business Ethics 52: 16978. Cohen, D., & Prusak, L. (2001) In Good Company: How Social Capital Makes Companies Work. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press. Collins, J. C. (2001) Good to Great. New York: Harper. Colquitt, J. A., Conlon, D. E., Wesson, M. J., Porter, O. L. H., & Ng, K. Y. (2001) Justice at the Millennium: A Meta-Analytic Review of 25 Years of Organizational Justice Research, Journal of Applied Psychology 86(3): 42545. Cooperrider, D. L., & Srivastva, S. (1987) Appreciative Inquiry in Organizational Life, Research in Organizational Change and Development, Vol. 1, pp. 12969. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press. Cropanzano, R., & Greenberg, J. (1997) Progress in Organizational Justice: Tunneling through the Maze, in C. L. Cooper & I. T. Robertson (eds) International Review of Industrial and Organizational Psychology, Vol. 12, pp. 31772. Chichester: John Wiley and Sons. Cunha, M. P. (2002) The Best Place to Be: Managing Control and Employee Loyalty in a Knowledge Intensive Firm, Journal of Applied Behavioral Science 38: 40115. Dean, J. W., Brandes, P., & Dharwadkar, R. (1998) Organizational Cynicism, Academy of Management Review 23: 34152. Edmondson, A. C. (1999) Psychological Safety and Learning Behavior in Work Teams, Administrative Science Quarterly 44: 35083. Farh, J., Podsakoff, P. M., & Organ, D. W. (1990) Accounting for Organizational Citizenship Behavior: Leader Fairness and Task Scope versus Satisfaction, Journal of Management 16(4): 70521. Fitness, J. (2000) Anger in the Workplace: An Emotion Script Approach to Anger Episodes between Workers and their Superiors, Co-Workers and Subordinates, Journal of Organizational Behavior 21: 14762. Flanagan, J. C. (1954) The Critical Incident Technique, Psychological Bulletin 51: 32758. Frost, P. J. (2003) Toxic Emotions at Work. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press. Fulmer, I. S., Gerhart, B., & Scott, K. S. (2003) Are the 100 Best Better? An Empirical Investigation of the Relationship between Being A Great Place to Work and Firm Performance, Personnel Psychology 56: 96593. Gabriel, Y. (1997) Meeting God: When Organizational Members come Face to Face with the Supreme Leader, Human Relations 50: 31542. Gabriel, Y. (1999) Organizations in Depth. London. SAGE. Gavin, J. H., & Mason, R. O. (2004) The Virtuous Organization: The Value of Happiness in the Workplace, Organizational Dynamics 33(4): 37992. Glaser, B., & Strauss, A. (1967) The Discovery of Grounded Theory. Strategies for Qualitative Research. London: Wiedenfeld and Nicholson. Gratton, L. (2004) The Democratic Enterprise. London: Financial Times/Prentice Hall. Grifn, W., & OLeary-Kelly, A. M. (eds) (2004) The Dark Side of Organizational Behaviour, pp. 2361. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. Hofstede, G. (1980) Cultures Consequences. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE. Jesuino, J. C. (2002) Latin Europe Cluster: From South to North, Journal of World Business 37: 819. Judge, T. A., Bono, J. E., Thorensen, C. J., & Patton, G. K. (2001) The Job Satisfaction-Job Performance Relationship: A Qualitative and Quantitative Review, Psychological Bulletin 127: 376407.

Downloaded from http://lea.sagepub.com by Tomislav Bunjevac on May 4, 2009

99

Leadership

5(1) Articles Kahn, W. A. (2005) Holding Fast: The Struggle to Create Resilient Caregiving Organizations. Hove: Brunner-Routledge. Kanov, J. M., Maitlis, S., Worline, M. C., Dutton, J. E., Frost, P. J., & Lilius, J. M. (2004) Compassion in Organizational Life, American Behavioral Scientist 47: 80827. Kets de Vries, M. F. R. (2001) Creating Authentizotic Organizations: Well-Functioning Individuals in Vibrant Companies, Human Relations 54: 10111. Kim, W. C., & Mauborgne, R. (1998) Procedural Justice, Strategic Decision Making and the Knowledge Economy, Strategic Management Journal 19: 32338. Kriger, M. P., & Hanson, B. J. (1999) A Value-Based Paradigm for Creating Truly Healthy Organizations, Journal of Organizational Change Management 12: 30217. Kuper, S. (2004) Ofce Angels, FT Weekend December 31: 12. Lawler, E. E. (2003) Treat People Right! How Organizations and Individuals can Propel each other into a Virtuous Spiral of Success. San Francisco, CA: Jossey Bass. Li, S., & Yeh, K. S. (2007) Maos Pervasive Inuence on Chinese CEOs, Harvard Business Review December: 1617. Ludema, J. D., Wilmot, T. B., & Srivastva, S. (1997) Organizational Hope: Reafrming the Constructive Task of Social and Organizational Inquiry, Human Relations 50: 101552. Luthans, F. (2002) The Need for and the Meaning of Positive Organizational Behavior, Journal of Organizational Behavior 23: 695706. Luthans, F., & Avolio, B. (2003) Authentic Leadership Development, in K. S. Cameron, J. E. Dutton, & R. E. Quinn (eds) Positive Organizational Scholarship, pp. 24158. San Francisco, CA: Berrett Koehler. Luthans, F., & Youssef, C. (2007) Emerging Positive Organizational Behavior, Journal of Management 33(3): 32149. McClelland, D. C. (1961) The Achieving Society. Princeton, NJ: Van Nostrand. McFarlin, D. B., & Sweeney, P. D. (2001) Cross-Cultural Applications of Organizational Justice, in R. Cropanzano (ed.) Justice in the Workplace: From Theory to Practice, pp.6795. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. Mintzberg, H. (1979) An Emerging Strategy of Direct Research, Administrative Science Quarterly 24: 5809. Moorman, R. H. (1991) Relationship between Organizational Justice and Organizational Citizenship Behaviors: Do Fairness Perceptions Inuence Employee Citizenship?, Journal of Applied Psychology 76: 84555. Morse, G. (2004) Executive Psychopaths, Harvard Business Review October: 202. Nelson, D., & Cooper, C. (eds) (2007) Positive Organizational Behavior. London: SAGE. Pfeffer, J. (1977) The Ambiguity of Leadership, Academy of Management Review 2: 10412. Plowman, D. A., Baker, L. T., Beck, T. E., Kulkarni, M., Solansky, S. T., & Travis, D. V. (2007) Radical Change Accidentally: The Emergence and Amplication of Small Change, Academy of Management Journal 50(3): 51543. Powley, E. H., Fry, R. E., Barrett, F. J., & Bright, D. S. (2004) Dialogic Democracy Meets Command and Control: Transformation through the Appreciative Inquiry Summit, Academy of Management Executive 18(3): 6780. Quick, J. C., & Macik-Frey, M. (2007) Healthy, Productive Work: Positive Strength through Communication Competence and Interpersonal Interdependence, in D. L. Nelson & C. L. Cooper (eds) Positive Organizational Behavior, pp. 2539. London: SAGE. Rego, A., & Cunha, M. P. (2008) Perceptions of Authentizotic Climates and Employee Happiness: Pathways to Individual Performance?, Journal of Business Research 61(7): 739751. Roos, I. (2002) Methods of Investigating Critical Incidents: A Comparative Review, Journal of Services Research 4: 193204.

100

Downloaded from http://lea.sagepub.com by Tomislav Bunjevac on May 4, 2009

Leadership

Exploring the Role of LeaderSubordinate Interactions Cunha et al. Seligman, M. E. P., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2000) Positive Psychology: An Introduction, American Psychologist 55: 514. Skarlicki, D. P., & Folger, R. (1997) Retaliation in the Workplace: The Roles of Distributive, Procedural, and Interactional Justice, Journal of Applied Psychology 82: 43443. Spinney, L. (2004) Snakes in suits, New Scientist August 21: 403. Spreitzer, G. M. (2006) Leading to Grow and Growing to Lead: Leadership Development Lessons From Positive Organizational Studies, Organizational Dynamics 35: 30515. Spreitzer, G. M., & Sonenshein, S. (2004) Toward the Construct Denition of Positive Deviance, American Behavioral Scientist 47: 82847. Spreitzer, G. M., & Sutcliffe, K. (2007) Thriving in Organizations, in D. L. Nelson & C. L. Cooper (eds) Positive Organizational Behavior, pp. 7485. London: SAGE. Sutcliffe, K. M., & Vogus, T. J. (2003) Organizing for Resilience, in K. S. Cameron, J. E. Dutton & R. E. Quinn (eds) Positive Organizational Scholarship, pp. 94110. San Francisco, CA: Berrett Koehler. Trevio, L. K., & Brown, M. E. (2007) Ethical Leadership: A Developing Construct, in D. L. Nelson & C. L. Cooper (eds) Positive Organizational Behavior, pp. 10116. London: SAGE. Vera, D., & Rodriguez-Lopez, A. (2004) Strategic Virtues: Humility as a Source of Competitive Advantage, Organizational Dynamics 33(4): 393408. Weisbord, M. R. (1976) Diagnosing your Organization: Six Places to Look for Trouble with or without Theory, Group and Organization Studies 1: 43047. Weiss, H. M., Suckow, K., & Cropanzano, R. (1999) Effects of Justice Conditions on Discrete Emotions, Journal of Applied Psychology 84(5): 78694. Weston, C., Gandell, T., Beauchamp, J., McAlpine, L., Wiseman, C., & Beauchamp, C. (2001) Analyzing Interview Data: The Development and Evolution of a Coding System, Qualitative Sociology 24(3): 38193. Wong, Y.-T., & Lui, H.-K. (2007) How to Improve Employees Commitment to their Line Manager: A Practical Study in a Chinese Joint Venture, Journal of General Management 32(3): 6177. Wright, T. A. (2004) The Role of Happiness in Organizational Research: Past, Present and Future Directions, Research on Occupational Stress and Well Being 4: 22164.

Miguel Pina e Cunha is associate professor at the Faculdade de Economia, Universidade Nova de Lisboa. He holds a PhD in management from Tilburg University. [email: mpc@fe.unl.pt] Rita Campos e Cunha is associate professor at the Faculdade de Economia, Universidade Nova de Lisboa. She holds a PhD in management from The University of Manchester, institute of Science and Technology. [email: rcunha@fe.unl.pt] Armnio Rego is assistant professor at the Universidade de Aveiro, Portugal. He holds a PhD in management from ISCTE (Instituto Superior de Ciencias do Trabalho e da Empresa. [email: armenio.rego@ua.pt]

Downloaded from http://lea.sagepub.com by Tomislav Bunjevac on May 4, 2009

101

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (587)

- Taxonomy of Aptitude Test Items: A Guide For Item WritersDokumen13 halamanTaxonomy of Aptitude Test Items: A Guide For Item WritersCarlo Magno100% (5)

- Exploring Co Leadership TALK Through INTERACTIONAL SOCIOLinguisticsDokumen23 halamanExploring Co Leadership TALK Through INTERACTIONAL SOCIOLinguisticstomor2Belum ada peringkat

- 360 Degree FeedbackDokumen2 halaman360 Degree Feedbacktomor2Belum ada peringkat

- Psychological Aspects of Natural Language Use Our Words Our SelvesDokumen34 halamanPsychological Aspects of Natural Language Use Our Words Our Selvestomor2Belum ada peringkat

- Existetntial Communication and LEADERSHIPDokumen18 halamanExistetntial Communication and LEADERSHIPtomor2Belum ada peringkat

- The Politics of GOSSIP and Denial in INTERORGANIZATIONAL RelationsDokumen22 halamanThe Politics of GOSSIP and Denial in INTERORGANIZATIONAL RelationstomorBelum ada peringkat

- Brain Exercise SoftwareDokumen3 halamanBrain Exercise SoftwaretomorBelum ada peringkat

- Thinking Skills ReviewDokumen48 halamanThinking Skills ReviewZigmas BigelisBelum ada peringkat

- hOW TO wRITE gOOD tEST CASESDokumen34 halamanhOW TO wRITE gOOD tEST CASESRam_p100% (12)

- Humor and Group EffectivenessDokumen25 halamanHumor and Group EffectivenesstomorBelum ada peringkat

- Human CompetenciesDokumen18 halamanHuman CompetenciesKrishnamurthy Prabhakar100% (2)

- Evaluating Strategic Leadership in Org TransformationsDokumen27 halamanEvaluating Strategic Leadership in Org Transformationstomor2Belum ada peringkat

- hOW TO wRITE gOOD tEST CASESDokumen34 halamanhOW TO wRITE gOOD tEST CASESRam_p100% (12)

- Abstract ReasoningDokumen13 halamanAbstract Reasoningm.rose60% (10)

- 60 Yrs of Human RelationsDokumen17 halaman60 Yrs of Human Relationstomor2Belum ada peringkat

- A Scenario Based Examination of Factors Impacting Automated Assessment SystemsDokumen18 halamanA Scenario Based Examination of Factors Impacting Automated Assessment Systemstomor2Belum ada peringkat

- Performin LEADERSHIP Toewards A New Research Agenda in Leadership StudiesDokumen17 halamanPerformin LEADERSHIP Toewards A New Research Agenda in Leadership Studiestomor2Belum ada peringkat

- Living Leadership A Systemic Constructionist ApproachDokumen26 halamanLiving Leadership A Systemic Constructionist Approachtomor2Belum ada peringkat

- Negative Capability and The Capacity To Think in The Present MomentDokumen12 halamanNegative Capability and The Capacity To Think in The Present Momenttomor2Belum ada peringkat

- Post Millennial Leadership ReffrainsDokumen14 halamanPost Millennial Leadership Reffrainstomor2Belum ada peringkat

- Existetntial Communication and LEADERSHIPDokumen18 halamanExistetntial Communication and LEADERSHIPtomor2Belum ada peringkat

- MBA and The Education of LEADERS EtonDokumen18 halamanMBA and The Education of LEADERS Etontomor2Belum ada peringkat

- Presidents of The US On LEADERSHIPDokumen31 halamanPresidents of The US On LEADERSHIPtomor2Belum ada peringkat

- Strategic LEADERSHIP An Exchange of LettersDokumen19 halamanStrategic LEADERSHIP An Exchange of Letterstomor2Belum ada peringkat

- The Academy of Chief Executives Programmes in The North East of EnglandDokumen25 halamanThe Academy of Chief Executives Programmes in The North East of Englandtomor2Belum ada peringkat

- The Enchantment of The Charismatic LeaderDokumen16 halamanThe Enchantment of The Charismatic Leadertomor2Belum ada peringkat

- The Impact of Goal Orientation On The Association Between Leadership Style and FOLLOWER Performance Creativity and Work AttitudesDokumen25 halamanThe Impact of Goal Orientation On The Association Between Leadership Style and FOLLOWER Performance Creativity and Work Attitudestomor2Belum ada peringkat

- The Romance of LEADERSHIP SCALE Cross Cultural Testing and RefinementDokumen19 halamanThe Romance of LEADERSHIP SCALE Cross Cultural Testing and Refinementtomor2Belum ada peringkat

- The Org Story As LeadershipDokumen21 halamanThe Org Story As Leadershiptomor2Belum ada peringkat

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (399)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (73)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5794)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2219)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (344)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (265)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)