Daniel, Gilles and Sornette, Didier and Wohrmann, Peter - Look-Ahead Benchmark Bias in Portfolio Performance Evaluation (200708)

Diunggah oleh

Edwin HauwertHak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Daniel, Gilles and Sornette, Didier and Wohrmann, Peter - Look-Ahead Benchmark Bias in Portfolio Performance Evaluation (200708)

Diunggah oleh

Edwin HauwertHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Look-Ahead Benchmark Bias in Portfolio Performance Evaluation

Gilles Daniel1 , Didier Sornette1 and Peter Wohrmann2 1 ETH Z rich, Department of Management, Technology and Economics u 2 University of Z rich u Switzerland [August 30, 2007] [version 3]

Abstract: Performance of investment managers are evaluated in comparison with benchmarks, such as nancial indices. Due to the operational constraint that most professional databases do not track the change of constitution of benchmark portfolios, standard tests of performance suffer from the look-ahead benchmark bias, when they use the assets constituting the benchmarks of reference at the end of the testing period, rather than at the beginning of the period. Here, we report that the look-ahead benchmark bias can exhibit a surprisingly large amplitude for portfolios of common stocks while most studies have emphasized related survival biases in performance of mutual and hedge funds for which the biases can be expected to be larger. We use the CRSP database from 1926 to 2006 and analyze the running top 500 US capitalizations to demonstrate that this bias can account for a gross overestimation of performance metrics such as the Sharpe ratio as well as an underestimation of risk, as measured for instance by peak-to-valley drawdowns. [We suggest a simple practical approach for detecting the presence of such a bias in ones data, based on the construction of constrained random portfolios.]

[August 30, 2007]

[version 3]

Introduction

How does one estimate the performance of a mutual fund, of a hedge-fund or more generally of a nancial investment? How does one quantify the quality of an investment strategy? A time-honored approach consists rst in selecting the funds and/or strategies of interest and then in quantifying their past performance over some time horizon. A large literature has followed this route, motivated by the eternal question of whether some investors/strategies systematically outperform others, with its implications for market efciency and investment opportunities. These backtests of investment performance may appear straightforward and natural at rst sight. However, a signicant literature has unearthed, studied and tried to correct for two ex-post conditioning biases, which continue to pollute even the most careful assessments. The survivorship bias: many estimates of persistence in investment performance are based on data sets that only contain funds or stocks that are in existence at the end of the sample period; see, e.g. (Brown et al. 1992, Grinblatt and Titman 1992). The corresponding survivorship bias is caused by the fact that poor performing funds/stocks are less likely to be observed in data sets that only contain the surviving funds/stocks, because the survival probabilities depend on past performance. Perhaps less appreciated is the fact that stocks themselves have also a large exit rate. For instance, Knaup (2005) examines the business survival characteristics of all establishments that started in the United States in the late 1990s when the boom of much of that decade was not yet showing signs of weakness, and nds that, if 85% of rms survive more than one year, only 45% survive more than four years. Bartelsman et al. (2003) conrm that a large number of rms enter and exit most markets every year in a group of ten OECD countries: data covering the rst part of the 1990s show the rm turnover rate (entry plus exit rates) to be between 15 and 20 per cent in the business sector of most countries, i.e. a fth of rms are either recent entrants or will close down within the year. This phenomenon of rm exits is not conned to small rms. Indeed, in the exhaustive CRSP database of about 26900 listed US rms, covering the period from Jan. 1926 to Dec. 2006 (Center for Research in Security Prices, http://www.crsp.com/), we nd that on average 25% of names disappeared after 3.3 years, 75% of names disappeared after 14 years and 95% of names disappeared after 34 years. The look-ahead bias: the use of information in a simulation that would not be available during the time period being simulated, usually resulting in an upward shift of the results. An example is the false assumption that earnings data become available immediately at the end of a nancial period. Another

Look-Ahead Benchmark Bias

G. Daniel, D. Sornette and P. Wohrmann

[August 30, 2007]

[version 3]

example is observed in performance persistence studies, in which it is common to form portfolios of funds/stocks based upon a ranking performed at the end of a rst period, together with the implicit or explicit condition that the funds/stocks are still in the selected ranks at the end of the second testing period. In other words, funds/stocks that are considered for evaluation are those which survive a minimum period of time after a ranking period (Brown et al. 1992). This bias is not remedied even if a survivorship free data-base is used, because it reects additional constraints on ranking. More generally, the fact that a data set is survivorship free does not imply that standard methods of analysis do not suffer from ex-post conditioning biases, which in one way or another may use (often implicit or hidden) present information which would not have been available in a real-time situation. In certain scientic elds concerned with forecasting, such as in earthquake prediction for instance, the community has recently evolved to the recognition that only real-time procedures can avoid such biases and test the validity of models (Jordan 2006, Schorlemmer et al. 2007). Previous works have addressed both survivorship and look-ahead biases. Brown et al. (1992) have shown that survivorship in mutual funds can introduce a bias strong enough to account for the strength of the evidence favoring return predictability previously reported. Carpenter and Lynch (1999) nd, among other results, that look-ahead biased methodologies (which require funds to survive a minimum period of time after a ranking period) materially bias statistics. ter Horst et al. (2001) introduce a weighting procedure based upon probit regressions modeling how survival probabilities depend upon historical returns, fund age and aggregate economy-wide shocks, which provides look-ahead bias-corrected estimates of mutual fund performances. Baquero et al. (2005) apply the methodology of ter Horst et al. (2001) to hedge-fund performance, which requires a well-specied model that explains survival of hedge funds and how it depends upon historical performance. ter Horst and Verbeek (2007) extend the look-ahead bias correction method of Baquero et al. (2005) to hedge-funds by correcting separately for additional self-selection biases that plague hedge-fund databases (underperformers do not wish to make their performance known while funds that performed well have less incentive to report to data vendors to attract potential investors). Here, we present a dramatic illustration of a variant of the look-ahead bias, which surprised us by its large amplitude. We are not dealing with mutual funds or hedge-funds, for which survival biases and look-ahead biases have been suggested to lead to overestimating expected returns by as much as 8% per year. We document a look-ahead bias in performance of portfolios investing solely in regular stocks.

Look-Ahead Benchmark Bias

G. Daniel, D. Sornette and P. Wohrmann

[August 30, 2007]

[version 3]

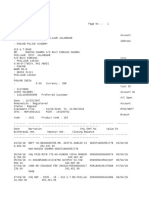

A classical example

In this context, the nature of the problem can be stated concretely as follows. Assume you want to back-test a given trading strategy on past data, namely on a pool of stocks such as the constituents of the S&P500 index on a given period, say January 2001 to December 2006. To do so, the natural approach would be the following: 1. Obtain the list of constituents of the S&P500 index at the present time (end of December 2006); 2. For each name (stock), retrieve the closing price time series for the given period; 3. Backtest the strategy on that data set, for instance by comparing it with the S&P500 benchmark. However, doing so introduces a formidable bias, and can easily lead to an erroneous analysis. Figure 1 dramatically illustrates the effect by comparing the performance of two investments. In the rst investment, which is subject to the look-ahead bias, we build $1 of an equally weighted portfolio invested in the 500 stocks constituting the S&P500 index at the end of the period (29 December 2006), and hold it from 1st January 2001 until 29th December 2006. Meanwhile, the second investment simply consists of buying $1 of the S&P500 index on 1st January 2001 and holding it until 29th December 2006. Both investments are buy-and-hold strategies and should have yielded similar performances if the constitution of the S&P500 index had not changed over this period.1 However, the list of constituents of the S&P500 index is updated, usually on a monthly basis, in order to include only the largest capitalizations of the US stock market at the current time. Consequently, this list of constituents cannot, by denition, contain a stock that for instance crashed in the recent past. Indeed, in such a case, the stock would have left the index and been replaced by another stock. The only difference in the two portfolios is that the rst investment uses a look-ahead information, namely it knows on 1st January 2001 what will be the list of constituents of the S&P500 index at the end of the period (29th December 2006). This apparently innocuous look-ahead bias leads to a huge difference in performance, as can be seen in Figure 1 and from simple statistics: the rst (respectively second) investment has an annual average compounded return of 6.4% (resp. 2.3%) and a Sharpe ratio (non-adjusted for

Since the S&P500 index is *not* equally weighted, we should expect a slight discrepancy between the evolution of portfolio 2 and the actual index.

1

Look-Ahead Benchmark Bias

G. Daniel, D. Sornette and P. Wohrmann

[August 30, 2007]

[version 3]

risk-free rate) of 0.4 (resp. 0.1). The rst investment has signicant better return but even more important smaller risks. Many managers would be happier to report Sharpe ratios in the range obtained for the rst investment. Investment strategies exhibiting this kind of performance would fuel interpretations in terms of evidence of departure from the efcient market hypothesis and/or of arbitrage opportunities. On the other hand, other pundits would observe that this look-ahead bias is really obvious, so that no one would fall in such a trivial trap. This quite reasonable assessment actually collides with one simple but often overlooked operational limitation: the change of constitution of nancial indices are most often not recorded in most standard professional databases, such as Bloomberg, Reuters, Datastream or Yahoo! Finance. As the standard goal for investment managers is at least to emulate or better to beat some index of reference, tests on comparative investments should use a dened set of assets on which to invest dened at the beginning of the period. However, because the list of constituents of the indices is unexpectedly challenging to retrieve2 , it is common practice to use the set of assets constituting the benchmarks of reference at the present time, rather than at the beginning of the period [Ref]. Then, necessarily, the kind of look-ahead bias that we report here will automatically pollute the conclusions, with sometimes dramatic consequences, as illustrated in Figure 1. We refer to this as the look-ahead benchmark bias. The rest of this note is devoted to a more systematic illustration of this lookahead bias over different periods, from 1926 to 2007.

The extent of the Look-Ahead Benchmark Bias

We use the data provided by the CRSP database, from which we extract the close price (daily), split factor (daily) and number of outstanding shares (monthly) for all US stocks from January 1926 to December 2006. This represents a total of 26892 different stocks. We decompose the time interval from January 1926 to December 2006 into 8 periods of 10 years each. For each period, we monitor the value of two portfolios. At the beginning of each ten-year period, the rst (resp. second) portfolio invests $1 equally weighted on the 500 largest stock capitalizations, as determined at the end (resp. start) of the ten-year period. The rst portfolio has by denition the look-ahead benchmark bias, while the second portfolio is exempt from it and

Standard & Poors themselves provide the list of constituents of the S&P500 index only since January 2000, while scripting Reuters, Bloomberg and Datastream returned only incomplete results. In fact, it appears that both the CRSP and Compustat databases are necessary to retrieve the list of constituents of the S&P500 index at any given point in time, and these databases are usually not accessible to practitioners.

2

Look-Ahead Benchmark Bias

G. Daniel, D. Sornette and P. Wohrmann

[August 30, 2007]

[version 3]

could have been implemented in real time. Figure 2 plots the time evolution of the value of the two portfolios. The inserted panels show that the Sharpe ratio and continuously-compounded average annual returns are much larger for portfolio 1 compared with portfolio 2. Figure 3 shows the time evolution of the value of an investment consisting of being long $1 in portfolio 1 and short $1 in portfolio 2. In other words, it shows the ratio of the value of portfolio 1 divided by the value of portfolio 2, for each of the 8 periods. By construction, this hedged long-short portfolio can be implemented only ex-post when backtesting, and not in real-time. Its performance is consistently good 3 over the 8 periods from 1926 to 2006, with a huge reduction of risks and better returns than the unbiased, ex-ante portfolio 2, thus demonstrating the signicance of the look-ahead bias. This result is robust with respect to the number of stocks selected in the two portfolios. The look-ahead benchmark bias documented here is related to the work of Cai and Houge (2007) who study how additions and deletions affect benchmark performance. Studying changes to the small-cap Russell 2000 index from 1979-2004, Cai and Houge (2007) nd that a buy-and-hold portfolio signicantly outperforms the annually rebalanced index by an average of 2.2% over one year and by 17.3% over ve years. These excess returns result from strong positive momentum of index deletions and poor long-run returns of new issue additions.

Only the 1937-1946 period exhibits a rather smaller gain, albeit still positive with a signicant reduction of risks.

Look-Ahead Benchmark Bias

G. Daniel, D. Sornette and P. Wohrmann

[August 30, 2007]

[version 3]

Constrained Random Portfolios

[Let us come back to the period from 1st January 2001 to 29th December 2006, shown in Figure 1 in order to test further the amplitude and robustness of the impact of the look-ahead benchmark bias. Investing on the 500 constituents of the S&P500 index at the end of the testing period (29th December 2006) amounts to bias the stock selection towards good performers. We illustrate that, as a consequence, non-informative random strategies exhibit very good to extremely good performance. We generate 10 portfolios, each of them implementing a random strategy. A random strategy opens only long positions (we buy rst, and sell later) on a subset of the 500 stocks, with an average leverage of 0.8 and an average duration per deal of 9 days which are common values. Given these constraints, the choice of the selected stock and the timing are random at each time step. We do not specify further the algorithm as all possible specic implementations give similar results. Figure 4 plots the time evolution of the value of $1 invested in each of these ten random portfolios on 1st January 2001. These random portfolios provide an average compounded annual return of (9.1 4)% with an excellent Sharpe ratio (with zero risk-free interest) of 2 0.8. The random portfolios (solid green lines) strongly outperform the S&P500 index (red dashed line), and simply diffuse around the look-ahead index (black dots) with an upward asymmetry. Similar results are obtained with other parameters of the random strategies.]

Look-Ahead Benchmark Bias

G. Daniel, D. Sornette and P. Wohrmann

[August 30, 2007]

[version 3]

Concluding remarks

We have reported a surprisingly large look-ahead benchmark bias, which results from an information on the future ranking of stocks due to their belonging to a benchmark index at the end of the testing period. We have argued that this lookahead benchmark bias is probably often present due to (i) the need for strategies or investments to prove themselves against benchmark indices and (ii) the nonavailability of the changes of composition of benchmark indices over the testing period. More generally, it is difcult if not impossible to completely exclude any look-ahead bias in simulations of the performance of investment strategies. As we reviewed in the introduction, one way to address these biases requires to rst recognize their existence, and then to model how survival probabilities depend on historical returns, fund age and aggregate economy-wide shocks. But, one can never be 100% certain that all biases have been removed. This is why other disciplines, such as in earthquake prediction for instance, have turned to real-time testing. Actually, real-time testing is a standard of the nancial industry, since cautious investors only invest in funds that have developed a proven track record established over several years. But as shown in the academic literature, success does not equate to skill and may not be predictive of future performance, as luck and survival bias can also loom large (Barras et al. 2007). There is a large and growing literature on how to test for data snooping and fund performance (see for instance (Lo and McKinlay 1990, Romano and Wolf 2005, Wolf 2006)). The problem is more generally related to the large issue of validating models ((Sornette et al. 2007) and references therein). Practitioners should be careful to test for the presence of such a look-ahead bias in their dataset prior to backtesting their trading strategy. [Here, we have proposed a simple and practical way to do so. Constrained random portfolios, which imitate as closely as possible the properties of the trading strategy about to be tested, such as its leverage, mean invested time and the turn-over, provide a straightforward approach to assess the probability that the performance of a given strategy can be attributed to chance.]

References

Baquero, G., J. ter Horst and M. Verbeek (2005) Survival, look-ahead bias, and the persistence in hedge fund performance, Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis 40 (3), 493-517. Barras, L., O. Scaillet and R. Wermers, False Discoveries in Mutual Fund Performance: Measuring Luck in Estimated Alphas, working paper (March

Look-Ahead Benchmark Bias

G. Daniel, D. Sornette and P. Wohrmann

[August 30, 2007]

[version 3]

2007) Bartelsman, E., Scarpetta, S., Schivardi, F. (2003) Comparative Analysis of Firm Demographics and Survival: Micro-level Evidence for the OECD Countries, OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 348, OECD Publishing, doi:10.1787/010021066480. Brown, S.J., W. Goetzmann, R. G. Ibbotson and S. A. Ross (1992) Survivorship bias in performance studies, Review of Financial Studies 5 (4), 553-580. Cai, J. and T. Houge (2007) Index Rebalancing and Long-Term Portfolio Performance, Available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=970839 Carpenter, J.N. and A. W. Lynch (1999) Survivorship bias and attrition effects in measures of performance persistence, Journal of Financial Economics 54 (3), 337-374. Grinblatt, M. and S. Titman (1992) The persistence of mutual fund performance, Journal of Finance 47, 1977-1984. Jordan, T. H. (2006) Earthquake Predictabillity: Brick by Brick, Seismological Research Letters 77 (1), 3-6. Knaup, A.E. (2005) Survival and longevity in the Business Employment Dynamics data, Monthly Labor Review, May 2005, 50-56. Lo, A.W. and A.C. McKinlay (1990) Data-snooping biases in tests of nancial asset pricing models, Review of Financial Studies 3 (3), 431-467. Romano, J.P. and M. Wolf (2005) Stepwise multiple testing as formalized data snooping, Econometrica 73 (4), 1237-1282. Schorlemmer, D., M. Gerstenberger, S. Wiemer, D.D. Jackson and D.A. Rhoades (2007) Earthquake Likelihood Model Testing, in Special Issue on Working Group on Regional Earthquake Likelihood Models (RELM), Seismological Research Letters 78 (1), 17. Sornette, D., A. B. Davis, K. Ide, K. R. Vixie, V. Pisarenko, and J. R. Kamm (2007) Algorithm for Model Validation: Theory and Applications, Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA 104 (16), 6562-6567. ter Horst, J.R., T.E. Nijman and M. Verbeek (2001) Eliminating look-ahead bias in evaluating persistence in mutual fund performance, Journal of Empirical Finance 8, 345-373. 9

Look-Ahead Benchmark Bias

G. Daniel, D. Sornette and P. Wohrmann

[August 30, 2007]

[version 3]

ter Horst, J. R. and M. Verbeek (2007) Fund Liquidation, Self-Selection and Look-Ahead Bias in the Hedge Fund Industry, Review of Finance, 1-28, doi:10.1093/rof/rfm012. Wolf, M. (2006) The Skill of Separating Skill from Luck, working paper Univ. Zurich (August).

Look-Ahead Benchmark Bias

10

G. Daniel, D. Sornette and P. Wohrmann

[August 30, 2007]

[version 3]

1.5 1.4 1.3 1.2 1.1 1 0.9 0.8 0.7 0.6 0.5 Jan01 exante (0.1, 2.3%) expost (0.4, 6.4%) S&P500 (0.1, 1.2%)

Portfolio value

Jan02

Jan03

Jan04 Date

Jan05

Jan06

Dec06

Figure 1: Evolution, from January 2001 to December 2006, of $1 invested in two equally weighted buy-and-hold portfolios made of the 500 constituents of the S&P500 index, respectively as in 1st January 2001 (ex-ante portfolio) and 29th December 2006 (ex-post portfolio). For reference, we also plot the historical value of the actual S&P500 index, normalised to 1 on 1st January 2001. The performance of the ex-ante and ex-post portfolios are reported in the upper left panel and measure respectively their Sharpe ratio (without zero risk-free interest rate) and continuously compounded average annual return.

Look-Ahead Benchmark Bias

11

G. Daniel, D. Sornette and P. Wohrmann

[August 30, 2007]

[version 3]

4.5 19271936: 19371946: 19471956: 19571966: 19671976: 19771986: 19871996: 19972006: (0.0, 0.6%) (0.1, 1.4%) (0.8, 9.6%) (0.8, 7.6%) (0.4, 4.6%) (1.0, 12.7%) (0.9, 14.3%) (0.7, 12.4%)

3.5 BuyandHold portfolio value

2.5

1.5

0.5

0 0

500

1000

1500 Trading days

2000

2500

3000

(a) biased, ex-post pickup

2.5 19271936: 19371946: 19471956: 19571966: 19671976: 19771986: 19871996: 19972006: (0.2, 5.0%) (0.0, 0.1%) (0.6, 6.4%) (0.4, 4.0%) (0.1, 1.2%) (0.6, 7.6%) (0.5, 6.7%) (0.3, 5.5%)

2 BuyandHold portfolio value

1.5

0.5

0 0

500

1000

1500 Trading days

2000

2500

3000

(b) ex-ante pickup

Figure 2: For each epoch of 10 years, we plot the evolution of portfolio 1 (upper panel) which invests $1 equally weighted on the 10 largest stock capitalizations, as determined at the end of the ten-year period and the evolution of portfolio 2 (lower panel) which invests $1 equally weighted on the 10 largest stock capitalizations, as determined at the start of the ten-year period. The inserts give the Sharpe ratio (with zero risk-free rate) and continuously-compounded average annual return. The discrepancy between these two gures helps us visualise the extent of the survival bias for the n=10 largest capitalizations throughout time. 12

Look-Ahead Benchmark Bias

G. Daniel, D. Sornette and P. Wohrmann

[August 30, 2007]

[version 3]

2.2 19271936: 19371946: 19471956: 19571966: 19671976: 19771986: 19871996: 19972006: (1.1, 5.9%) (0.7, 1.5%) (2.9, 3.0%) (2.3, 3.5%) (2.1, 3.4%) (2.6, 4.7%) (2.6, 7.2%) (2.0, 6.5%)

BuyandHold portfolio value

1.8

1.6

1.4

1.2

0.8 0

500

1000

1500 Trading days

2000

2500

3000

Figure 3: Time evolution of the value of an investment consisting in being long $1 in a portfolio 1 equally weighted on the 500 largest stock capitalizations at the end of each period and short $1 in a portfolio 2 equally weighted on the 500 largest stock capitalization at the end of each period, with compounding the returns. The inset shows the Sharpe ratios (with zero risk-free interest) and compounded annual return for the 8 periods.

Look-Ahead Benchmark Bias

13

G. Daniel, D. Sornette and P. Wohrmann

[August 30, 2007]

[version 3]

3 exante (0.1, 2.3%) expost (0.4, 6.4%) S&P500 (0.1, 1.2%) Random 2.5

Portfolio value

1.5

0.5 Jan01

Jan02

Jan03

Jan04 Date

Jan05

Jan06

Dec06

Figure 4: [As in Figure 1, with in addition 5 random portfolios.]

Look-Ahead Benchmark Bias

14

G. Daniel, D. Sornette and P. Wohrmann

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (121)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (588)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (266)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (399)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5794)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (344)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (895)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- Master Budget and Responsibility Accounting Chapter Cost Accounting Horngreen DatarDokumen45 halamanMaster Budget and Responsibility Accounting Chapter Cost Accounting Horngreen Datarshipra_kBelum ada peringkat

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- Risk Management TemplateDokumen72 halamanRisk Management TemplatehaphiBelum ada peringkat

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (73)

- Asset and Liability ManagementDokumen57 halamanAsset and Liability ManagementMayur Federer Kunder100% (2)

- Cost Accounting, 14e, Chapter 4 SolutionsDokumen39 halamanCost Accounting, 14e, Chapter 4 Solutionsmisterwaterr80% (15)

- Secret of Successful Traders - Sagar NandiDokumen34 halamanSecret of Successful Traders - Sagar NandiSagar Nandi100% (1)

- Carolan, C. (1998) - Spiral Calendar - TheoryDokumen21 halamanCarolan, C. (1998) - Spiral Calendar - Theorystummel6636100% (8)

- Disney Pixar Case AnalysisDokumen4 halamanDisney Pixar Case AnalysiskbassignmentBelum ada peringkat

- MAS-04 Relevant CostingDokumen10 halamanMAS-04 Relevant CostingPaupauBelum ada peringkat

- Jio Fiber Tax Invoice TemplateDokumen5 halamanJio Fiber Tax Invoice TemplatehhhhBelum ada peringkat

- Aquaponics: Fish and Crop Plants Share The Same Recycled Water in LaosDokumen1 halamanAquaponics: Fish and Crop Plants Share The Same Recycled Water in LaosAquaponicsBelum ada peringkat

- Test Bank For Supply Chain Management A Logistics Perspective 9th Edition CoyleDokumen8 halamanTest Bank For Supply Chain Management A Logistics Perspective 9th Edition Coylea385904759Belum ada peringkat

- Pfea 1Dokumen1 halamanPfea 1Von Andrei MedinaBelum ada peringkat

- 25Dokumen1 halaman25Edwin HauwertBelum ada peringkat

- 22Dokumen1 halaman22Edwin HauwertBelum ada peringkat

- 20Dokumen1 halaman20Edwin HauwertBelum ada peringkat

- 23Dokumen1 halaman23Edwin HauwertBelum ada peringkat

- 21Dokumen1 halaman21Edwin HauwertBelum ada peringkat

- 24Dokumen1 halaman24Edwin HauwertBelum ada peringkat

- POKER Science - Aay2400.fullDokumen13 halamanPOKER Science - Aay2400.fullEdwin HauwertBelum ada peringkat

- 19Dokumen1 halaman19Edwin HauwertBelum ada peringkat

- 10Dokumen1 halaman10Edwin HauwertBelum ada peringkat

- 8Dokumen1 halaman8Edwin HauwertBelum ada peringkat

- 18Dokumen1 halaman18Edwin HauwertBelum ada peringkat

- 9Dokumen1 halaman9Edwin HauwertBelum ada peringkat

- 11Dokumen1 halaman11Edwin HauwertBelum ada peringkat

- 6Dokumen1 halaman6Edwin HauwertBelum ada peringkat

- 2008H SornetteDokumen73 halaman2008H SornetteEdwin HauwertBelum ada peringkat

- 7Dokumen1 halaman7Edwin HauwertBelum ada peringkat

- 4Dokumen1 halaman4Edwin HauwertBelum ada peringkat

- 3Dokumen1 halaman3Edwin HauwertBelum ada peringkat

- CorporatePresentation Jan 2012Dokumen33 halamanCorporatePresentation Jan 2012Edwin HauwertBelum ada peringkat

- 5Dokumen1 halaman5Edwin HauwertBelum ada peringkat

- 2Dokumen1 halaman2Edwin HauwertBelum ada peringkat

- 1Dokumen1 halaman1Edwin HauwertBelum ada peringkat

- EAPC Kampala 2011Dokumen31 halamanEAPC Kampala 2011Edwin HauwertBelum ada peringkat

- Financial Management: Weighted Average Cost of CapitalDokumen11 halamanFinancial Management: Weighted Average Cost of Capitaltameem18Belum ada peringkat

- General Mills Prediction Market Thesis VDokumen106 halamanGeneral Mills Prediction Market Thesis VEdwin HauwertBelum ada peringkat

- Gundlach Mirror MirrorDokumen66 halamanGundlach Mirror MirrorEdwin HauwertBelum ada peringkat

- Lighthouse Special Report Who Moved My RecessionDokumen17 halamanLighthouse Special Report Who Moved My RecessionEdwin HauwertBelum ada peringkat

- Optimal Capital StructureDokumen14 halamanOptimal Capital StructuretomydaloorBelum ada peringkat

- Chalmers, Keryn G. and Godfrey, Jayne M. and Navissi, Farshid - The Systematic Risk Effect of Hybrid Securities' Classifications (2007)Dokumen26 halamanChalmers, Keryn G. and Godfrey, Jayne M. and Navissi, Farshid - The Systematic Risk Effect of Hybrid Securities' Classifications (2007)Edwin HauwertBelum ada peringkat

- BUSINESS Plan PresentationDokumen31 halamanBUSINESS Plan PresentationRoan Vincent JunioBelum ada peringkat

- Banking Management Chapter 01Dokumen8 halamanBanking Management Chapter 01AsitSinghBelum ada peringkat

- CHAPTER - 01 Agri. Business ManagementDokumen187 halamanCHAPTER - 01 Agri. Business Management10rohi10Belum ada peringkat

- Tutorial AnswerDokumen14 halamanTutorial AnswerJia Mun LewBelum ada peringkat

- Test Item File To Accompany Final With Answers2Dokumen247 halamanTest Item File To Accompany Final With Answers2Chan Vui YongBelum ada peringkat

- IME PRINT FinalDokumen18 halamanIME PRINT FinalNauman LiaqatBelum ada peringkat

- MCQ On Banking Finance & Economy-1Dokumen4 halamanMCQ On Banking Finance & Economy-1Shivarajkumar JayaprakashBelum ada peringkat

- Income DeterminationDokumen82 halamanIncome DeterminationPaulo BatholomayoBelum ada peringkat

- Accounting of Clubs & SocietiesDokumen13 halamanAccounting of Clubs & SocietiesImran MulaniBelum ada peringkat

- The Accounting Principles Board - ASOBATDokumen14 halamanThe Accounting Principles Board - ASOBATblindleapBelum ada peringkat

- GPNR 2019-20 Notice and Directors ReportDokumen9 halamanGPNR 2019-20 Notice and Directors ReportChethanBelum ada peringkat

- Course Outline For Bus Org IIDokumen6 halamanCourse Outline For Bus Org IIMa Gabriellen Quijada-TabuñagBelum ada peringkat

- Strategies To Reduce Supply Chain Disruptions in GhanaDokumen126 halamanStrategies To Reduce Supply Chain Disruptions in GhanaAlbert HammondBelum ada peringkat

- Interim and Continuous AuditDokumen4 halamanInterim and Continuous AuditTUSHER147Belum ada peringkat

- Research Proposal of Role of Cooperatives On Women EmpowermentDokumen9 halamanResearch Proposal of Role of Cooperatives On Women EmpowermentSagar SunuwarBelum ada peringkat

- Worksafe Construction Safety Survey HandoutDokumen2 halamanWorksafe Construction Safety Survey Handouthesam khorramiBelum ada peringkat

- 1538139921616Dokumen6 halaman1538139921616Hena SharmaBelum ada peringkat

- Tax AccountantDokumen2 halamanTax Accountantapi-77195400Belum ada peringkat

- AIS Cycle PDFDokumen25 halamanAIS Cycle PDFWildan RahmansyahBelum ada peringkat