2010 - Divergent Multipoint Strategies Within Competitive Triads PDF

Diunggah oleh

Nuno CoelhoDeskripsi Asli:

Judul Asli

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

2010 - Divergent Multipoint Strategies Within Competitive Triads PDF

Diunggah oleh

Nuno CoelhoHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Business Horizons (2010) 53, 4957

www.elsevier.com/locate/bushor

When strategies collide: Divergent multipoint strategies within competitive triads

John W. Upson a,*, Annette L. Ranft b

a b

Richards College of Business, University of West Georgia, Carrollton, GA 30118-3030, U.S.A. College of Business, Florida State University, Tallahassee, FL 32306-1110, U.S.A.

KEYWORDS

Competitive dynamics; Multipoint competition; Blind spots; Competitive release

Abstract As market barriers fall and market boundaries blur, rms are becoming increasingly broad in their scope of operations and markets. This expansion in a rms scope intensies competition as the interaction between rivals spreads across many markets. To succeed as a rm, managers must then take a multi-market approach to competition. Critical to success is an understanding of how rival contact across markets can affect a rms competitive behavior. This understanding exists for competition between two rms; however, few rms face only one rival across multiple markets. We expand the focus on one competitor and explore congurations of competitive triads. We explain why triadic competition is more dynamic and deviates somewhat from dyadic competition, and set the foundation for exploring competition among a broader set of competitors. # 2009 Kelley School of Business, Indiana University. All rights reserved.

1. An inconvenient guest

Technological innovations and globalization continue to change todays competitive landscape (Hitt, Keats, & DeMarie, 1998). Among these changes, industry barriers have fallen, allowing for easy entry by new competitors. Witness how traditional insurance providers State Farm and Allstate were quick to enter the investment brokerage industry following a change in government regulations. Industry boundaries have become blurred and difcult to dene. One may nd it difcult to precisely dene the boundaries of the cell phone, personal digital

* Corresponding author. E-mail addresses: jupson@westga.edu (J.W. Upson), aranft@cob.fsu.edu (A.L. Ranft).

assistant (PDA), and portable music player industries. The net effect of these landscape changes is that rms are increasingly meeting rivals in more and more markets (Korn & Baum, 1999). From this trend a phenomenon known as multipoint competition has emerged, and it reveals how the alignment of rivals across their respective markets can affect rm behavior (Chen, 1996). In considering multipoint competition, one must recognize that a rms competitive moves are not isolated within the markets where they occur, but rather are part of the rms overall strategy to compete with its rivals across all the markets in which they meet. One primary factor of multipoint competition that affects rms strategies is multimarket contact, or the degree to which rms meet competitors in more than one distinct market (Korn & Baum, 1999).

0007-6813/$ see front matter # 2009 Kelley School of Business, Indiana University. All rights reserved. doi:10.1016/j.bushor.2009.09.001

50 Studies have revealed that the level of multimarket contact between two rms affects each rms behavior as they compete for position across markets (Baum & Korn, 1999; Haveman & Nonnemaker, 2000). Much of what we currently know about multipoint competition comes from analysis of dyadic, or two rm, competition. However, one concern with studying dyadic competition is that it assumes a rms competitive moves are all targeted at a particular rival. Although dyadic competition occurs in some industries (e.g., in the soft drinks industry between The Coca-Cola Company and PepsiCo), rms normally face multiple rivals (Baum & Korn, 1999; Fu, 2003). For example, General Electric Company, Rolls Royce, and Pratt & Whitney all compete in the aircraft engine industry and meet in many product markets within the industry. Omitting any one of these rms in a study of competition would severely limit the results and might risk associating a competitive move with the wrong rival. To gain a better understanding of multipoint competition and help managers formulate their strategies, we acknowledge that rms do not compete with just one rival across product markets. The study of multiple rivals in a multimarket setting is a complicated task. We take a rst step toward understanding this complex phenomenon by investigating competitive behaviors among three rms, or triads, in competition. By triads, we mean the study of a rm and its two most frequent rivals across all product markets in which the rm competes. Our decision to study triads was based on two factors. First, managers dene their main rivals through a process of cognitive categorization (Reger & Huff, 1993). This is a form of sense making in which managers assess organizational similarities to subjectively dene their rivals (Porac & Thomas, 1990, 1994). Previously, when managers have been asked to identify their number of competitors, responses varied widely yet averages generally fell no lower than two competitors (Clark & Montgomery, 1998; Gripsrud & Gronhaug, 1985; Hauser & Wernerfelt, 1990; Narayana & Markin, 1975). This provided the motivation to move beyond the study of dyads and include greater numbers of competitors. Second, we limit our discussion to the number of competitors that are likely to have the greatest impact on competition. For guidance, we turned to the United States computer related manufacturing and software industries, where we found that the top three market share leaders within 139 product markets collectively own 91% market share on average. Accordingly, we chose to focus on a rm and its two most frequent multipoint rivals, or triads. By considering three rather than two rms in competition, we do not suggest that the third rm

J.W. Upson, A.L. Ranft is a recent entrant. Rather, the third rm is simply a multimarket rival that would be overlooked in a dyadic study. Also, in studying triads, we do not suggest that competition is limited to only three rms. We accept that rms may have many rivals. Focusing on triads allows for simplication of analysis while providing relevant points of discussion that are applicable to a broad range of managers. Next, we clarify the effects of competition between dyads in a multipoint competitive setting, and then explore triads.

2. One on one: Competitive dyads

Research in competitive dynamics generally accounts for rm level factors that affect competition (Hannan & Freeman, 1989; Porter, 1980). An underlying theme of this research is that the interdependence of rms is a key determinant of competition (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983). One rms success or failure is affected by another rm. Multipoint competition research is unique however, in that it explores the interdependence of rms across multiple product markets, and acknowledges that the competitive actions of rivals are not contained within a single product market but can spill over into other common product markets. Several studies have observed the effects of multimarket contact on the intensity at which rivals compete, and have found three competitive stances: indifference, aggression, and forbearance. Indifference occurs where there are few product markets in which rms meet. In this case, rms tend to be less aware of or threatened by one another, and so they do not actively compete. However, as multimarket contact increases, the likelihood of aggression increases. Firms become aware of each other, and ght aggressively to dene their competitive positions and stake their claims in markets (Baum & Korn, 1999; Haveman & Nonnemaker, 2000). Their competitive actions can include those that test a rivals capabilities, as well as defensive actions that display their rms unwillingness to be pushed around. At the highest levels of multimarket contact, a unique phenomenon occurs: rivals reduce their competition (Baum & Korn, 1999). At these highest levels of multimarket contact, mutual forbearance results. Mutual forbearance is a form of tacit collusion through which rms decrease their level of competition and take a sort of live and let live approach (Jayachandran, Gimeno, & Varadarajan, 1999). This collusion is benecial to each rm as they can realize increased performance in terms of higher prices, higher margins, and greater market share stability (Evans & Kessides, 1994;

When strategies collide: Divergent multipoint strategies within competitive triads Heggestad & Rhoades, 1978; Jans & Rosenbaum, 1996). However, one must not mistake the decrease in competition and associated benets as an indication that rms ignore one another. Rather, rms become intimately aware of their multipoint rivals actions and intentions in order to mutually forbear. There are two primary reasons that rms engage in mutual forbearance, and both center on the risks that a rm incurs by initiating an attack on a rival. First, a rm that initiates an aggressive action toward a multipoint rival is uncertain as to where the rival will retaliate; in other words, the rivals point of retaliation is unknown. The point of retaliation could occur in a product market in which losses to the aggressor are large, but losses to the retaliator are small (Karnani & Wernerfelt, 1985; Porter, 1980). Second, the aggressor is uncertain as to the retaliation scope, or the number of product markets that will be affected by the rivals retaliation. The scope of a rivals retaliation could be far reaching. Aggression toward a rival in one product market could prompt a rivals retaliation in several product markets (Edwards, 1955). An underlying concern is that competition could escalate into an all-out war and severely damage one or both rms. An example of a total war occurred in the early 1980s when Braniff Airlines initiated a price war against American Airlines, a much larger competitor. The intensity of the price war escalated, with both competitors rmly committed to holding their positions. The confrontation ended when Braniff was forced to shut down, ending 54 years of service (Ketchen, Snow, & Hoover, 2004; Sloan, 2005). Because there is a risk that an aggressive action could accidently escalate into an all-out war, rms refrain from even isolated battles with rivals of high multimarket contact (Porter, 1981). In addition to multimarket contact, there is one other primary factor that affects a rms competitive stance: rm scope, or the number of product markets in which a rm has presence. Scope is important because multimarket contact consists of the number of product markets shared with rivals divided by rm scope (Gimeno & Jeong, 2001). When rivals have different scopes, although the number of common product markets between them may be equal, their multipoint contact and resulting views of competition will differ. For an example of the effects of scope on multipoint competition, consider the rivalry between Hewlett-Packard (HP) and Dell. HP and Dell both compete in the desktop computer, laptop computer, and printer product markets, and also meet as rivals in several other product markets. However, their scopes differ. Dells scope is relatively narrow, and centers mainly on computers and peripherals.

51

HPs scope is broad, and includes computers and peripherals like Dell, but also includes such product markets as calculators, business services, commercial printers, and networking solutions. Between them, Dell meets HP in exactly the same number of product markets that HP meets Dell. However, differing scopes indicate a difference in multimarket contact. Given the number of common product markets shared with Dell, HewlettPackards broad scope suggests that it has relatively low multimarket contact with Dell. Dells multimarket contact with HP, on the other hand, is relatively high because of Dells narrower scope. This affects competition because if Dells multimarket contact is sufciently high, it will seek mutual forbearance with HP. Meanwhile, if HPs multimarket contact is in the mid-range, it will seek to compete aggressively against Dell. In summary, two rivals that share a given number of common product markets can each have unique competitive intentions based on their relative level of multimarket contact. It is worth noting that larger rms tend to compete in more product markets than smaller rms. A large difference in rivals scope may indicate a large difference in size, as well. If one rm is overly dominant, multimarket contact is of little consequence (Golden & Ma, 2003). While we highlight differences in scope and the resulting conict of strategy between rms, we limit our discussion to situations in which no difference in size or scope is so large as to omit any effect of multimarket contact. We have so far discussed the basics of competition in a multipoint setting as they are currently understood from research on competitive dyads. We seek next to enhance this knowledge by asking: How does the consideration of greater numbers of multipoint rivals affect the previously observed relationships in dyadic competition? In answering this question, we rst discuss briey some complexities of moving to a focus on triadic competition. Then we apply this knowledge to the study of specic congurations of triads.

3. No longer one on one: Considering a third player

Few competitive situations involve only two rms. The study of triads is important because it reveals how competition might change as the number of multipoint rivals increases above the traditional dyad. Drawing from classic industry-level analysis of competition (Scherer & Ross, 1990), we expect that triads will be more aggressive than dyads when their level of multimarket contact indicates

52 aggression. We also expect that triads will seek mutual forbearance at lower levels of multimarket contact than dyads. In addition, triadic competition highlights phenomena within the competitive dynamics literature that may not likely occur within dyadic competition. Two rivals may engage in intense competition and fail to monitor the third competitor. This occurred in the computer hardware industry, where International Business Machines Corp. (IBM) and HP were locked in intense competition and allowed Dell to gain signicant market share (Mateyaschuk, 1998). Also, two rivals may tacitly collude to stand up to the third competitor. For example, Williamson Medical Center and St. Thomas Health Services aligned forces to lobby the Health Services and Development Agency in opposition to HCAs proposed expansion in Nashville, Tennessee (Wood, 2006). In examining multimarket competition we suggest that each competitive conguration be considered individually, and considerations be made for the level of multimarket contact, rm scope, and respective rm strategy. In transitioning the focus of study from dyads to triads, one complexity that arises is with the calculation of multimarket contact. In dyadic competition, the gross number of common product markets is easily identied. However, triads are more complex. A simplied look at competition between the three United States automakers provides a good example. General Motors Corporation (GM), Ford Motor Company, and Chrysler all offer vehicles in the coupe, sedan, crossover, and SUV product markets. However, only GM and Ford compete in the product market for large SUVs, and only Chrysler competes in the product market for minivans. The complexity arises as to what qualies as triadic multimarket contact. One way to measure multimarket contact is to assume that each rm in a product market experiences the same degree of multimarket contact (Evans & Kessides, 1994; Hughes & Oughton, 1993). However, as is evident by the automaker example, each rm is actually unique in its multimarket contact with rivals. An alternative is to assume that each competitor within a product market has an equal impact on the focal rm (Gimeno & Woo, 1996). However, this measure is also incomplete as competitors vary in many of their characteristics. Suggesting that each competitor is the same dilutes the effects of any single rival. Finally, as discussed previously, multimarket contact has been viewed as a property of the unique relationship between two rms, or dyad (Baum & Korn, 1999). Again, this can lead to incomplete predictions, as we demonstrate by revisiting the automakers competition from the perspective of

J.W. Upson, A.L. Ranft Ford. Ford and GM compete in many of the same product markets. Perhaps managers at Ford consider their multimarket contact with GM to be high enough to seek mutual forbearance. Turning to Chrysler, it is unique in that it offers a minivan, which Ford does not; yet, Ford offers trucks, which Chrysler does not. Ford managers might consider their multimarket contact with Chrysler to be medium, and then seek to compete aggressively. However, in triadic competition across all their common product markets, it would be difcult for Ford to aggressively compete against Chrysler and forbear against GM. Because of the spillover effects of competition, Fords aggression toward Chrysler might disrupt its mutual forbearance against GM. These complexities suggest that dyadic competition is important, but it must not be considered in isolation. All of a rms dyadic relations are important but not independent. Triadic competitive scenarios must take into account the effects of each dyadic relationship in the product market, and also the interaction between these dyadic relationships. Next, we take a rst step in that direction by considering several triadic competitive scenarios.

4. Memorable games: Congurations of triads

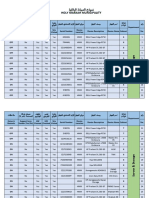

Being aware of the complexities involved in explaining competition among triads, we attempt to maintain simplicity in two ways. First, we consider only three levels of multimarket contact (low, medium, and high), and, respectively, three associated competitive stances (indifference, aggression, and forbearance). As discussed before, these relationships have been observed in dyadic competition and provide the basis for our discussion on triads. Second, we limit our discussion to only those triadic competitive congurations that are most likely to differ from dyadic competition. In triadic competition, there are ten unique competitive congurations that can exist among three competitors, each capable of having one of three competitive stances (Table 1). We investigated four of these congurations as listed in the uppermost portion of the table. The remaining six congurations were not considered, because at least one rm in each of these congurations realizes low multimarket contact, and subsequently is indifferent to competition with the other two rms. Firms that are indifferent toward rivals have little impact on competition (Haveman & Nonnemaker, 2000). In such situations, the level of competition is likely driven by the remaining rms in the triad, and these congurations were appropriately discarded. The four congurations that we focus on

When strategies collide: Divergent multipoint strategies within competitive triads

Table 1. Triadic Cong Triadic competitive congurations Firm 1 Firm 2 Firm 3 Effects Four congurations in which all three rms are aware of each other. Multimarket contact is an important factor of competition. Example Microsoft, Sony, and Nintendo are locked in intense competition over video game consoles. Proctor & Gamble, Johnson & Johnson, and Kimberly-Clark refrain from entering certain product markets where one of the rivals is present. Smaller industry participants Samsung and Motorola simultaneously dropped prices in attempts to take market share from industry leader Nokia. U-Haul and Budget Truck Rental have been locked in intense competition, allowing Penske to grow its industry presence without drawing serious retaliation. Three congurations in which only two rms are focused on each other. Their competitive intensity likely follows predictions from dyadic multipoint competition. Two congurations in which only one rm is focused on the others. The effects of multimarket contact are likely minor. One conguration in which no rm is focused on the others. Multimarket contact has little effect on competition.

53

Aggressive

Aggressive

Aggressive

Forbearance

Forbearance

Forbearance

Forbearance

Forbearance

Aggressive

Forbearance

Aggressive

Aggressive

5 6

Indifferent Indifferent

Aggressive Forbearance

Aggressive Forbearance

Indifferent

Forbearance

Aggressive

Indifferent

Indifferent

Aggressive

Indifferent

Indifferent

Forbearance

10

Indifferent

Indifferent

Indifferent

offer insight as to how triadic competition differs from dyadic competition. These are discussed next.

4.1. Playing for keeps

Studies of dyadic competition have observed that when two rms meet in several but not all product markets, they compete aggressively (Baum & Korn, 1999). The rms competitive actions are a means of dening their competitive positions and staking

claims to particular product markets (Haveman & Nonnemaker, 2000). A third rm, also experiencing medium multimarket contact, is likely a threat to, and threatened by, its two rivals. Tit-for-tat attacks increase as each rm tests the viability of the other. This effectively increases competition because each rm has an interest in establishing its presence in relation to its two rivals, and attempts to gain a superior position across their common product markets.

54 Applying the effects of triads to the relationship between multimarket contact and competitive intensity indicates that when all three rms realize medium multimarket contact, the peak of competitive intensity is higher for triads than it would be for dyads. This is consistent with traditional arguments from industrial organization economics in that the more competitors, the greater the competition (Scherer & Ross, 1990). Further, it would appear plausible that any increase in the number of competitors, also with an aggressive competitive stance, would increase the peak of competitive intensity. The dynamics of three aggressive multipoint rivals can be seen in the videogame industry, where Microsoft, Sony, and Nintendo are locked in intense competition over videogame consoles. Triadic level competition has risen to a high level, with each rm attempting to create blockbuster console releases. The intense competition has even affected their alliance relationships, and further increased competition. For example, software publishers are becoming less willing to sign exclusive deals with any of the videogame console manufacturers. Because there is no dominant console manufacturer, the income opportunities available to software developers are limited in exclusive relationships. Software publishers instead seek to make their games compatible with all console systems. The effect of this will be to increase competition among console manufacturers even further, as it will become more difcult for any rm to differentiate itself based on its selection of games.

J.W. Upson, A.L. Ranft an aggressive action, it risks receiving retaliation in any product market that it shares with J&J, Kimberly-Clark, or both. This increased risk causes triads characterized by high multimarket contact to be more adverse to aggression than dyads. The increased pressure to seek forbearance effectively causes rms in triadic competition to engage in mutual forbearance at lower levels of multimarket contact than they would in dyadic competition. In its product market overlap with rivals, a rm may not experience dyadic market commonality high enough to seek forbearance with any one rival. However, the combined effects of two rivals multimarket contact with a focal rm increases the rms risk of escalated confrontation across its product markets, and causes the rm to become less aggressive at high multimarket contact than it would in dyadic competition. Inspection of any supermarket inventory will reveal signs of mutual forbearance between Johnson & Johnson, Proctor & Gamble, and Kimberly-Clark. J&J, known as the baby company, does not make diapers, whereas P&G has its well-known Pampers brand and Kimberly-Clark has its Huggies brand. P&G, known as the soap and shampoo company, does not make baby shampoo, yet J&J and KimberlyClark do (DAveni, 2002). Finally, Kimberly-Clark has only a limited line of adult shampoo, whereas J&J and P&G have extensive lines. These rms overlap considerably in the other product markets where they compete, and have effectively reduced their level of aggressiveness to respect their rivals presence in certain product markets. In both of the cited competitive congurations, three aggressive rivals and three forbearing rivals, general predictions from dyadic competition hold to a greater degree: rms aggressively compete under medium multimarket contact and forebear under high multimarket contact. The next two competitive congurations discussed highlight unique situations that may only arise with more than two competitors. In these cases, competitors pursue divergent strategies: some forebear and some are aggressive.

4.2. A friendly match

Dyadic competitive studies have observed that two rivals experiencing high multimarket contact are reluctant to compete aggressively. Consequently, the rms mutually forbear. A third rival, also experiencing high multimarket contact, will cause competition to decrease further because each rm has more product markets at risk in triadic competition than in dyadic competition. For example, consider the competition between Proctor & Gamble (P&G), Johnson & Johnson (J&J), and Unilever. In dyadic competition, P&G encounters J&J in some product markets. By also considering its product market overlap with Kimberly-Clark, P&G has additional product markets at risk. Kimberly-Clark is in some of the product markets where both P&G and J&J are present, and is also present in product markets where P&G is present but J&J is not. In total, the number of product markets P&G has exposed to its rivals in triadic competition is greater than the number exposed to either rival in dyadic competition. If P&G chooses to initiate

4.3. Two play friendly and the third wants to battle

In dyadic competition, two rivals meeting in a relatively high percent of product markets will mutually forbear (Haveman & Nonnemaker, 2000). However, the presence of a third rm, having medium multimarket contact and a preference for aggression, will likely increase competition for two reasons. First, the high level of competition from the aggressive rm will cause the two forbearers to increase their aggression in order to defend themselves and

When strategies collide: Divergent multipoint strategies within competitive triads maintain their positions. Second, rms engaged in mutual forbearance tend to be very familiar with one another and their respective capabilities. Mutual forbearance is, after all, a form of tacit collusion. Facing a common rival, the two forbearers may pool their competitive efforts and gang-up on the aggressor. The phenomenon of gang-up has traditionally been presented as collusion between large market share owners that have little reason to compete directly, and instead seek an outlet for competition, or competitive release (Barnett, Greve, & Park, 1994). This outlet comes in the form of an inferior, smaller rm that acts as a target for the two dominant rms. But perhaps size is not the only factor. Firm scope might also determine when gangup occurs. For a given number of common product markets, smaller-scope rms may seek to forbear while larger-scope rms may seek aggression. This aggression from a larger-scope rm is likely not welcomed by the two smaller-scope forbearers. Having extensive knowledge of each other and the ability to tacitly collude, the forbearers may retaliate against the aggressor. By coordinating their efforts, the forbearers become a greater threat to the aggressor, because their combined scope is broader than either scope alone and allows for more points of attack against the aggressive rm. By targeting the aggressor and not each other, the forbearers might succeed in repelling the aggressor, thereby bringing about the stable environment they both seek. Such gang-up has occurred in the cell phone industry, where smaller industry participants Samsung and Motorola simultaneously dropped prices in attempts to take market share from industry leader Nokia.

55

4.4. Two clash and the third plays friendly

From the study of dyads, we understand that two rivals experiencing medium multimarket contact ercely compete in order to establish superiority (Baum & Korn, 1999). The presence of a third rm, which realizes high multimarket contact and seeks forbearance, will not notably affect competition for two reasons. First, the forbearer behaves so as not to draw attention from the two aggressors. Second, the two aggressors are not threatened by the forbearer because the forbearer presents less of a risk across product markets to the aggressors than vice versa. The reason is that for a given number of common product markets between rms, those rms that compete in few product markets realize higher multimarket contact than those rms that compete in many product markets. This indicates that the two aggressors have greater scopes than

the forbearer. In turn, due to its high level of multimarket contact, the forbearer has a greater percent of product markets at risk to retaliation than the aggressors, which only experience medium multimarket contact. However, in congurations of two aggressors and one forbearer, there might be an opportunity for the forbearer to increase aggression without considerably increasing risk. Because the two aggressors are locked in intense competition, they may overlook some of the forbearers actions. This provides an opportunity for the forbearer to take advantage of the aggressors blind spots (Zajac & Bazerman, 1991). Blind spots are judgmental mistakes resulting from strategic decision makers poor identication and faulty assumptions about competitors (Zahra & Chaples, 1993). Blind spots cause rms to inaccurately perceive the signicance of events, perceive events incorrectly, or perceive them very slowly (Porter, 1980). Traditionally, blind spots have been observed in larger rms and exploited by smaller rms. A prime example occurs when larger market share owners of a concentrated industry become complacent, tacitly collude, and lose their competitive edge. This creates weaknesses that are not apparent to them, but are visible to other smaller rms. However, this phenomenon may also occur between rms of large and small scope. In our case, two medium multimarket contact rms will focus their attention on one another because of their reciprocal aggressive competitive stances. This provides the opportunity for a third rm with smaller scope to identify and exploit potentially lucrative blind spots. This competitive conguration is present in the truck rental and leasing industry. Leaders U-Haul International Inc. and Avis Budget Group, Inc. (Budget Truck Rental) have been locked in intense competition. Each has diversied into self-storage facilities, moving supplies, and supply chain management, thereby increasing their scope. Meanwhile, Penske, with a limited scope, has been able to grow its presence in the industry without drawing serious retaliation from either industry leader.

5. Avoid leaving the court

As we have discussed, changes in the competitive landscape are breaking down barriers and changing competition. As competition becomes increasingly complex, both opportunities and threats await. It is important that managers understand the dynamics of competition so that they can use these changes to their advantage as they face more and different competitors.

56 Unfortunately, those rms whose managers cannot manage the complexity will be forced out of a product market. To survive within a product market, managers can benet by considering three important factors. First, competition is not limited to a particular product market, but extends to every point where rivals meet. Managers should therefore develop their rms strategy in any one product market as part of an overall strategy against its rivals across product markets. In formulating this strategy, it is important for managers to know which product markets are most critical to the rms overall success. Some considerations may be the product markets where the rm has the greatest share, product markets that allow the rm to exploit its core competencies, or product markets that have the greatest potential for future growth. Also important is knowledge as to which rivals a rm meets most frequently across product markets. These rivals likely know a lot about the rm, and vice versa. Therefore, they pose signicant mutual threats to each other. Finally, managers should be cognizant of the presence of key rivals in critical product markets. This may be especially concerning, but can also be an opportunity for mutual forbearance. The second factor that managers should consider is the reciprocal strategies of each rival, because one rms strategy affects anothers. By appreciating the perspective of ones rival, managers can gain insight into its strategy and use this knowledge in the creation of their own strategy. By correctly anticipating rival behavior and correctly modifying the rms strategy, managers can stay one step ahead of rivals. Third, although the cognitive limits of managers may control the extent to which they monitor rivals, we recommend that managers focus on more than one rival, and then consider the synergies with the rivals strategies. Because rivals may enter and leave product markets frequently, managers must continuously scan the competitive landscape to maintain a current understanding of product market participants and the threats they pose. However, the awareness should not end here. Managers must also take a collective view of their rivals strategies, and attempt to identify opportunities that may only exist between multiple competitors. We have highlighted gangup and blind spots as two opportunities that multicompetitor multipoint competition can present. These phenomena illustrate just two of the many ways in which competition between multiple rms may result in opportunities for those rms that take a holistic view of the product markets. The bottom line is that managers must learn to weave their rms strategy within and around

J.W. Upson, A.L. Ranft their collective rivals strategies so as to gain the most benet.

6. Final thoughts

The multipoint competition philosophy of competitive dynamics has gained many adherents. However, multipoint competition has been limited in its applicability to rms, especially when analyzing their competitor base. By considering multiple competitors, great opportunities await managers who are vigorous in their analysis. Given the challenges in todays competitive product markets, it is imperative that rms carefully analyze their specic competitive positions to verify that their current strategy toward a rival in a product market is in line with the rms overall strategy against its many rivals across many product markets. Without commitment and an understanding of the associated challenges and requirements, managers may be better off focusing their efforts and resources elsewhere. Managers must also seriously consider their potential to change as an organization. Awareness of ones competitors will do little unless managers are able to coordinate the rms actions across different product markets and internal divisions. Those rms that are dedicated to competitor analysis and strategy alignment will gain the most.

References

Barnett, W. P., Greve, H., & Park, D. Y. (1994). An evolutionary model of organizational performance. Strategic Management Journal, 15(Special Issue), 1128. Baum, J. A. C., & Korn, H. J. (1999). Dynamics of dyadic competitive interaction. Strategic Management Journal, 20(3), 251278. Chen, M.-J. (1996). Competitor analysis and inter-rm rivalry: Toward a theoretical integration. Academy of Management Review, 21(1), 100134. Clark, B. H., & Montgomery, D. B. (1998). Deterrence, reputations, and competitive cognition. Management Science, 44(1), 6282. DAveni, R. A. (2002, August 15). A forceeld to deect competitors. Financial Times Online. Retrieved February 2, 2009, from http://proquest.umi.com/pqdweb?index=1&did=149534371& SrchMode=2&sid=1&Fmt=3&VInst=PROD&VType=PQD&RQT= 309&VName=PQD&TS=1235143953&clientId=30336 DiMaggio, P., & Powell, W. (1983). The iron cage revisited: Institutionalized isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational elds. American Sociological Review, 48(2), 147160. Edwards, C. D. (1955). Conglomerate bigness as a source of power. In the National Bureau of Economics Research conference report, Business concentration and price policy (pp. 331352). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

When strategies collide: Divergent multipoint strategies within competitive triads

Evans, W. N., & Kessides, I. (1994). Living by the golden rule: Multimarket contact in the U.S. airline industry. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 109(2), 341366. Fu, W. W. (2003). Multimarket contact of U.S. newspaper chains: Circulation competition and market coordination. Information Economics and Policy, 15(4), 501519. Gimeno, J., & Jeong, E. (2001). Multimarket contact: Meaning and measurement at multiple levels of analysis. In Baum, J. A. C. & Greve, H. R. (Eds.), Multiunit organization and multimarket strategy: Advances in strategic management. (Vol. 18, pp.357408). Oxford, UK: JAI Press. Gimeno, J., & Woo, C. Y. (1996). Hypercompetition in a multimarket environment: The role of strategic similarity and multimarket contact in competitive de-escalation. Organization Science, 7(3), 322341. Golden, B. R., & Ma, H. (2003). Mutual forbearance: The role of intrarm integration and rewards. Academy of Management Review, 28(3), 479493. Gripsrud, G., & Gronhaug, K. (1985). Structure and strategy in grocery retailing: A sociometric approach. Journal of Industrial Economics, 33(3), 339347. Hannan, M. T., & Freeman, J. (1989). Organizational ecology. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Hauser, J. R., & Wernerfelt, B. (1990). An evaluation cost model of consideration sets. Journal of Consumer Research, 16(6), 393 408. Haveman, H. A., & Nonnemaker, L. (2000). Competition in multiple geographic markets: The impact on growth and market entry. Administrative Science Quarterly, 45(2), 232267. Heggestad, A. A., & Rhoades, S. A. (1978). Multimarket interdependence and local market competition in banking. Review of Economics and Statistics, 60(4), 523532. Hitt, M. A., Keats, B. W., & DeMarie, S. M. (1998). Navigating in the new competitive landscape: Building strategic exibility and competitive advantage in the 21st century. Academy of Management Executive, 12(4), 2242. Hughes, K., & Oughton, C. (1993). Diversication, multi-market contact, and protability. Economica, 60(238), 203224. Jans, I., & Rosenbaum, D. I. (1996). Multimarket contact and pricing: Evidence from the U.S. cement industry. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 15(3), 391412. Jayachandran, S., Gimeno, J., & Varadarajan, P. R. (1999). Theory of multimarket competition: A synthesis and implications for marketing strategy. Journal of Marketing, 63(3), 4966.

57

Karnani, A., & Wernerfelt, B. (1985). Multiple point competition. Strategic Management Journal, 6(1), 8796. Ketchen, D. J., Snow, C. C., & Hoover, V. L. (2004). Research on competitive dynamics: Recent accomplishments and future challenges. Journal of Management, 30(6), 779804. Korn, H. J., & Baum, J. A. C. (1999). Chance, imitative, and strategic antecedents to multimarket contact. Academy of Management Journal, 42(2), 171193. Mateyaschuk, J. (1998, September 21). Dell stakes success on build-to-order strategy. InformationWeek, 701, 134136. Narayana, C. L., & Markin, R. J. (1975). Consumer behavior and product performance: An alternative conceptualization. Journal of Marketing, 39(4), 16. Porac, J. F., & Thomas, H. (1990). Taxonomic mental models in competitor denition. Academy of Management Review, 15(2), 224240. Porac, J. F., & Thomas, H. (1994). Cognitive categorization and subjective rivalry among retailers in a small city. Journal of Applied Psychology, 79(1), 5466. Porter, M. E. (1980). Competitive strategy: Techniques for analyzing industries and competitors. New York: Free Press. Porter, M. E. (1981). The contributions of industrial organizations to strategic management. Academy of Management Review, 6(4), 609620. Reger, R. K., & Huff, A. S. (1993). Strategic groups: A cognitive perspective. Strategic Management Journal, 14(2), 103 123. Scherer, F. M., & Ross, S. (1990). Industrial market structure and economic performance (3rd ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifin. Sloan, C. (2005). Airchive timetables and route maps. Airchive. com. Retrieved May 19, 2007, from http://www.airchive. com/ SITE%20PAGES/TIMETABLES-AMERICAN.html Wood, E. T. (2006, May 5). Hospital competitors gang up against HCAs Spring Hill plan. Nashville Post. Retrieved February 2, 2009, from http://www.nashvillepost.com/news/2006/ 5/5/comment_hospital_competitors_gang_up_against_hcas_ spring_hill_plan Zahra, S. A., & Chaples, S. S. (1993). Blind spots in competitive analysis. Academy of Management Executive, 7(2), 728. Zajac, E. J., & Bazerman, M. H. (1991). Blind spots in industry and competitor analysis: Implications of interrm (mis)perceptions for strategic decisions. Academy of Management Review, 16(1), 3756.

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (399)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (266)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (588)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2259)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (344)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)

- HP Marketing MixDokumen8 halamanHP Marketing MixPruthvi RajaBelum ada peringkat

- Considerations For Choosing HP Agentless ManagementDokumen8 halamanConsiderations For Choosing HP Agentless ManagementkyntBelum ada peringkat

- 3103GF Halinski MichaelDokumen6 halaman3103GF Halinski MichaelrjjrerBelum ada peringkat

- Hewlett-Packard LTD Metro Park Cloughfern Avenue Newtownabbey BT37 0ZR WWW - hp.Com/Uk/SelbDokumen1 halamanHewlett-Packard LTD Metro Park Cloughfern Avenue Newtownabbey BT37 0ZR WWW - hp.Com/Uk/SelbsilvercrissBelum ada peringkat

- SM9 30 - EventServicesDokumen140 halamanSM9 30 - EventServicesSandesh KiraniBelum ada peringkat

- Making Your HP Glance Peak PerformDokumen25 halamanMaking Your HP Glance Peak PerformrahilsusantoBelum ada peringkat

- Compaq Was A Company Founded in 1982 That Developed, Sold, and SupportedDokumen4 halamanCompaq Was A Company Founded in 1982 That Developed, Sold, and SupportedMrunalkanta DasBelum ada peringkat

- Bluetooth Peripheral Device Driver For Windows 7 32 Bit Download For HPDokumen3 halamanBluetooth Peripheral Device Driver For Windows 7 32 Bit Download For HPkoko FLFLBelum ada peringkat

- HP Latex CatalogDokumen28 halamanHP Latex CatalogJerson OlarteBelum ada peringkat

- HP Spectre x360 Convertible 15-Eb0065nr: Undisputed PerformanceDokumen2 halamanHP Spectre x360 Convertible 15-Eb0065nr: Undisputed PerformanceFarrukh ShehzadBelum ada peringkat

- HP Troubleshooting AssessmentDokumen6 halamanHP Troubleshooting AssessmentViswaBelum ada peringkat

- P9000 Auto LUN User Guide P9500 Disk ArrayDokumen66 halamanP9000 Auto LUN User Guide P9500 Disk Arraybsie002Belum ada peringkat

- History of Meg WhitmanDokumen8 halamanHistory of Meg Whitman1990sukhbirBelum ada peringkat

- How To Disable Remote Firmware Upgrades - c03154309 - HP Business Support CenterDokumen4 halamanHow To Disable Remote Firmware Upgrades - c03154309 - HP Business Support CenterMaver XapBelum ada peringkat

- HP Bad Code ErrorDokumen2 halamanHP Bad Code Errorrachidi1Belum ada peringkat

- HP Installation and Startup Service For HP BladeSystem C Class InfrastructureDokumen7 halamanHP Installation and Startup Service For HP BladeSystem C Class InfrastructurenimdamskBelum ada peringkat

- HP UltraSlim Docking Station (D9Y32AA)Dokumen1 halamanHP UltraSlim Docking Station (D9Y32AA)stnt tgBelum ada peringkat

- Managing Global SystemDokumen29 halamanManaging Global SystemAashish ThoratBelum ada peringkat

- Servers - Preventive Maintenance Report 3 April 2023Dokumen7 halamanServers - Preventive Maintenance Report 3 April 2023Muhammad UsmanBelum ada peringkat

- What Is The Distinctive Competence of The Followin.Dokumen2 halamanWhat Is The Distinctive Competence of The Followin.farel ayengBelum ada peringkat

- PC - Magazine 11.april.2006Dokumen166 halamanPC - Magazine 11.april.2006LikinmacBelum ada peringkat

- HP-UX 11.0 Installation and Update GuideDokumen168 halamanHP-UX 11.0 Installation and Update GuideAgustin GonzalezBelum ada peringkat

- CMS Site Preparation and Installation ManualDokumen164 halamanCMS Site Preparation and Installation ManualRobson BarrosBelum ada peringkat

- Apple Incorporation (Case Analysis) : College of AccountancyDokumen54 halamanApple Incorporation (Case Analysis) : College of AccountancybeeeeeeBelum ada peringkat

- Add Print Model To Comments Field Release NotesDokumen4 halamanAdd Print Model To Comments Field Release NotescdaBelum ada peringkat

- RPCPPE June 30, 2022Dokumen23 halamanRPCPPE June 30, 2022Early RoseBelum ada peringkat

- SM9.2 Compatibility MatrixDokumen7 halamanSM9.2 Compatibility MatrixDinesh VelBelum ada peringkat

- Hewlett-Packard Global Soft Ltd.Dokumen6 halamanHewlett-Packard Global Soft Ltd.Suman JhaBelum ada peringkat

- Belarc Advisor 22 Oct 2015Dokumen14 halamanBelarc Advisor 22 Oct 2015Antonis HajiioannouBelum ada peringkat

- Luis Daniel Solano CastilloDokumen9 halamanLuis Daniel Solano CastilloOmar Benigno RodriguezBelum ada peringkat