READ 4534 Sample Paper

Diunggah oleh

Elizabeth Anderson SwaggertyHak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

READ 4534 Sample Paper

Diunggah oleh

Elizabeth Anderson SwaggertyHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

1 L.

RICHARDS: COMPREHENSION STRATEGY INSTRUCTION

Extending Comprehension Strategy Instruction through Think-Alouds, Guided Reading and Literature Discussions L. M. Richards Summer 2012

2 L. RICHARDS: COMPREHENSION STRATEGY INSTRUCTION

Extending Comprehension Strategy Instruction through Think-Alouds, Guided Reading and Literature Discussions The ultimate goal of reading is to construct meaning and understanding through comprehension. According to Pardo (2004), comprehension is, one of the most important skills for students to develop if they are to become successful and productive adults (p. 278). This skill does not just occur naturally in readers. In order for readers to learn how to comprehend text, they must be taught strategies for comprehension explicitly and directly (Pardo, 2004). However, it is not enough to simply teach students these strategies. In order for comprehension instruction to be successful, teachers need a framework where comprehension strategies can be modeled by the teacher, practiced by the students and extended through authentic student dialogue about text (Mariotti, 2010). The purpose of this paper is to provide teachers with a framework to increase the quality of their comprehension strategy instruction through the use of teacher thinkalouds, guided reading groups, and literature discussions. To better understand this framework for successful comprehension strategy instruction, one must first have an understanding for what it means to comprehend text. What is Comprehension? Comprehension is a complicated process and is one that has been explained and defined in numerous ways. Pardo (2004) defines comprehension in relation to teachers, explaining that it is a process of constructing meaning through text interaction that involves the readers prior knowledge and previous experience, information in the

3 L. RICHARDS: COMPREHENSION STRATEGY INSTRUCTION text, and the stance the reader takes in relationship to the text (p. 272). This definition indicates that many factors contribute to comprehension. Kucer and Rosenblatt (as cited in Pardo, 2004) conclude that comprehension is a transaction that occurs between a specific reader and a specific text. Many factors contribute to such a transaction. For example, the reader brings specific traits and characteristics that are uniquely his and that are applied with every text and reading situation (Pardo, 2004). Other factors that contribute to transaction with a text include the sociocultural context of each specific situation and the features of each text. It is when these factors come together that a transaction between the reader and the text can occur and meaning can emerge, or comprehension takes place (Pardo, 2004). It is up to the teacher to support the student in such a critical exchange. Teachers can support students in their comprehension by ensuring that every student has the specific skill knowledge needed to properly transact with text. This is where comprehension strategy instruction begins. Comprehension Strategy Instruction In a research study, Ness (2011) considered instruction to be comprehension based when teachers did any of the following: explicitly described a comprehension strategy along with when and how to use it, a teacher or student modeled a strategy, students practiced a strategy during guided reading using the gradual release of responsibility model, students used a strategy independently or a teacher focused on vocabulary instruction. Ness (2011) found that 25% of language arts instructional time was spent on explicit reading comprehension strategy instruction as listed above. This percentage is definitely an improvement over Durkins study in the late 1970s that found

4 L. RICHARDS: COMPREHENSION STRATEGY INSTRUCTION that 1% of such instructional time was spent on reading comprehension instruction (as cited in Ness, 2011, p. 109). However, there is still plenty of room for growth when it comes to teachers use of such comprehension strategies (Ness, 2011). Therefore, teachers must first be aware of proven, successful comprehension strategies. There are many reading comprehension strategies that teachers can choose to teach their students. Some of these strategies include predicting/prior knowledge, comprehension monitoring, visualizing, clarifying, asking questions and summarizing (Lang, 2009; Marcell, DeCleene, & Juettner, 2010; Ness, 2011). Teachers must also understand the importance of not teaching the above skills solely in isolation. Lloyd (2004) describes the importance of referring back to previously learned strategies when teaching new strategies and Marcell, DeCleene and Juettner (2010) discuss the importance of allowing students the opportunity to practice using such strategies simultaneously so that students learn to use multiple strategies while they are reading independently. After all, the goal of teaching reading comprehension strategies is that students can transfer the use of reading comprehension strategies to their independent reading. While it may seem overwhelming for teachers to find ways to teach these reading comprehension strategies to their students successfully, there are methods that many teachers have found to be extremely effective. The success behind such methods is the use of the Gradual Release of Responsibility Model (Lloyd, 2004). Once teachers understand how the gradual release of responsibility model works, they are able to use such a framework to guide their students to successful reading comprehension.

5 L. RICHARDS: COMPREHENSION STRATEGY INSTRUCTION The gradual release of responsibility model is a technique that involves shifting the responsibility of using comprehension strategies to the student from the teacher over the course of time. Lloyd (2004) proves this technique to be extremely successful when teaching reading comprehension strategies. When using this particular technique, the teacher begins with think-alouds and then moves on to guided reading groups. The model ends with students participating in authentic literature discussions (Lloyd, 2004). While it may seem daunting to many teachers to implement such a strategy, it is reassuring to know that it can be broken down into three separate, yet sequential activities including teacher think-alouds, guided reading groups and literature discussions. Implementing the Gradual Release of Responsibility Model Think-Alouds Within this particular framework, the first step is implementing a teacher thinkaloud. This is where the teacher first introduces, explains, and models a particular reading comprehension strategy (Lloyd, 2004). More specifically, Harris and Hodges define think-alouds as a metacognitive technique or strategy in which a teacher verbalizes thoughts aloud while reading a selection orally, thus modeling the process of comprehension (as cited in Block & Israel, 2004, p. 154). During the think-aloud, the teacher holds the majority of the responsibility for using the strategy while the students get a chance to listen to the teacher and learn from them. During this time, the students hold very little responsibility, but they may try the strategy while they listen to the teacher model it for them (Lloyd, 2004). It is during

6 L. RICHARDS: COMPREHENSION STRATEGY INSTRUCTION this activity that students get to observe the successful use of a particular comprehension strategy put into practice. Block and Israel (2004) describe highly-effective think-alouds as demonstrating how to select a reading comprehension strategy at a specific point in a text along with describing why it would be effective in helping the reader. Over time, students will begin to see how and when to use the reading comprehension strategies being modeled. Because comprehension strategies occur in the mind, it is not surprising that students actually want their teachers to model comprehension strategies for them (Block & Israel, 2004). One study by C.C. Block (2004) indicated that students actually wanted their teachers to better explain the reading processes and describe what their teachers did in their minds to help them comprehend what they read (as cited in Block & Israel, 204, p. 155). It can best be explained in the words of Walker (2005), Thinking aloud makes this internal process observable (p. 688). While this process can be difficult for teachers to model, it is has been proven to increase reading comprehension (Walker, 2005). The proven success of think-alouds makes it a necessary component to a teachers reading comprehension instruction. It is even more successful when followed by guided reading groups. Guided Reading We cannot expect our students to become proficient in using reading comprehension strategies independently unless they get a chance to practice using them under teacher guidance and scaffolding. During guided reading, the teacher still holds more responsibility than the student, but the students hold more than they did during the think-aloud (Lloyd, 2004). Ford and Opitz (2008) do a great job of describing

7 L. RICHARDS: COMPREHENSION STRATEGY INSTRUCTION this technique as being, less about modeling and more about coaching (p. 314). This is also a good time for the teacher to monitor and assess students as they practice using the strategies as suggested by Lloyd (2004). By assessing students during this time, teachers are able to see student progress with strategies and help those that are struggling with the current strategy at hand. Teachers implement guided reading groups by placing students in groups with other students that are on similar reading levels or that use similar processes (Fountas & Pinnell, 1996). The teacher then chooses a text that can be read at an instructional level with minimal support from the teacher and the students can use to practice a newly learned comprehension strategy (Fountas & Pinnell, 1996). This gives the students a chance to practice the comprehension strategy without having to spend a great deal of time struggling over individual words. Fountas & Pinnell (1996) advise that the teacher introduce a text to the small group, work briefly with individuals in the group as they read it, select one or two teaching points to present to the group following the reading, and ask the students to take part in an extension of the text. This type of structure that guided reading follows is called the Before, During, and After format. Before the reading, the teacher will introduce a text to the group and possibly ask some questions that will be answered through reading. This is when the teacher gets the students interested in the story and the children begin to ask questions. During the reading, the students read the story using the specific comprehension strategies and the teacher listens in to note the strategy usage of each student. The teacher will also provide scaffolding for students when appropriate. After reading, the teacher may revisit a few problem areas for

8 L. RICHARDS: COMPREHENSION STRATEGY INSTRUCTION teaching opportunities and all members discuss the story that was read. The teacher may also wish to engage the students in extending or responding activities such as journal writing (Fountas & Pinnell, 1996). One successful type of response activity that follows the gradual release of responsibility model is the use of literature discussion groups. Literature Discussions The last piece of this framework puzzle includes literature discussions. During these authentic discussions, the role of responsibility changes once again as the teachers release even more responsibility to the students as they read a particular text and independently use the comprehension strategies they have been previously practicing and then share those strategies as they discuss the text in their literature discussion groups (Lloyd, 2004). Mariotti (2010) makes clear the importance of providing students time for authentic talk about text which opens the door for deepened comprehension. Liang (2009) indicated that, When response activities and comprehension strategies are combined, classroom instruction can enhance student engagement and understanding of a text, enrich student response, and improve students awareness of their own strategic reading (p.330). Therefore, response activities such as literature discussions best benefit students when they include comprehension strategy discussion with actual text discussion. Teachers can implement two main types of literature circles in their classrooms that have shown to be effective for previous educators; those with assigned student

9 L. RICHARDS: COMPREHENSION STRATEGY INSTRUCTION roles and those without (Berne & Clark, 2008; Lloyd, 2004; Marcel et al., 2004). Both have been proven to be successful in different situations. Lloyd (2004) argues that the traditional literature circles that include specific assigned roles often lacked authentic discussion. Babbitt (2004) found that when roles were assigned most student talk was actually focused on classroom assignments (as cited in Lloyd, 2004, p. 115) Lloyd found that in her own classroom, students were more willing to have open, authentic talk about literature when they first were taught the questioning strategy. This kept the teacher from always having to ask the questions and made the discussions student-driven instead of teacher-driven. Keehn and Roser (as cited in Lloyd, 2004) found that as soon as students began to participate in asking questions, 26% of their sustained talk centered more on making inferences, 22% of the time they informed peers about discoveries in texts, and 20% of the time was spent interpreting newly discovered information to the group (p. 116). In other words, assigned roles simply were not needed. Authentic discussions were happening and comprehension strategies were being utilized. Berne and Clark (2008) also explain how such literature discussion groups provide a way for students to develop comprehension strategies. They describe how teachers can take literature discussion groups and require the students to explain the strategies they used to comprehend while reading the text. The students then share those strategies with their group members, all the while learning to think mtetacognitively about their own comprehension process. This is a great way for students to become fluent in using and recognizing these strategies (Berne & Clark,

10 L. RICHARDS: COMPREHENSION STRATEGY INSTRUCTION 2008). In other words, students will be able to take what they have learned and apply it to independent reading. Other educators may argue that the use of specific roles is beneficial to students when talking about text in literature discussion groups. Marcel, DeCleene and Juettner (2010) described a reciprocal teaching approach that involved four specific comprehension strategies: predicting, clarifying, asking questions and summarizing. Marcel created a successful construction site themed system in which she taught the previous four comprehension strategies and each student took one of the strategies to focus on while reading a particular text. The students then gathered in their groups and discussed the text according to their roles. After students became proficient in their roles, they would switch to a new one. At the end of the discussion, the students would discuss which comprehension strategy helped them the most and why. No matter which type of literature discussion a teacher chooses to implement in his/her classroom, it is important to remember that this is where the student carries the majority of the responsibility for comprehension. In other words, this is where the students talk more and the teacher talks less (Marcell, DeCleene & Juettner, 2010). While it may be hard for many teachers to give up that control, the above indicates that the release of student responsibility is proven to aid in comprehension strategy instruction and should be considered by all reading teachers. Conclusion If we want our students to be successful and productive adults, it is imperative that we teach them comprehension strategies explicitly and directly (Pardo, 2004). Ness (2010) cited numerous reasons why comprehension strategy instruction is necessary in

11 L. RICHARDS: COMPREHENSION STRATEGY INSTRUCTION the classroom. Therefore, it is also necessary that educators are aware of a framework for teaching such strategies. Such a framework is based off of the gradual release of responsibility model where the teacher first holds the majority of the responsibility for using a comprehension strategy and slowly releases it to the students. This framework begins with the use of teacher think-alouds, moves to guided reading groups and concludes with authentic literature discussions (Lloyd, 2004). After such instruction, it is the hope of every teacher that the student will be able to carry the use of the comprehension strategies into independent reading. Reflection Before researching information for this paper, I knew that comprehension strategy instruction was important, but I was reluctant about how to include it in my own future classroom. I had learned about teacher think-alouds, guided reading, and literature discussions in previous classes, but I did not understand how they could all fit together in to support comprehension instruction in my classroom. I now feel more confident that I can implement this framework in my own classroom successfully. I also better understand how it fits in the gradual release of responsibility model and buy into the statements made by Marcell, DeCleene, and Juettner (2010) related to students talking more and teachers talking less. I understand that students need to see me model specific comprehension strategies by speaking aloud what I am thinking internally while reading a text. After direct modeling, students need a chance to practice those same strategies under my guidance while reading a text. This gives them a chance to build the skill knowledge with proper scaffolding as needed. Lastly, students need authentic discussions with

12 L. RICHARDS: COMPREHENSION STRATEGY INSTRUCTION their peers about a text along with discussion about how they used those comprehension strategies while reading the text. This framework slowly releases responsibility to the student in such a way so that after literature discussions they can hopefully transfer the strategy use to successful independent reading. I really liked reading Loyds (2004) article the idea of literature discussion and cannot wait to implement this format in my classroom to foster student-led instruction and thinking about text. I honestly cannot wait to try comprehension instruction as I have described it in this paper in my own classroom. Earlier this semester, I read an article that sparked my interest for comprehension instruction. It is so extremely important that students know specific comprehension strategies and how to use them. If not, they are likely to go through their educational career without ever being able to truly extract meaning from a text. Therefore, it is my job as an educator to prepare my students for their future by teaching them such strategies in a successful framework.

13 L. RICHARDS: COMPREHENSION STRATEGY INSTRUCTION References Berne, J. I., & Clark, K. F. (2008). Focusing literature discussion groups on comprehension strategies. The Reading Teacher, 62(1), 74-79. doi:10.1598/RT.62.1.9 Block, C., & Israel, S. E. (2004). The ABCs of performing highly effective think-alouds. Reading Teacher, 58(2), 154-167. doi:10.1598/RT 58.24 Ford, M. P., & Opitz, M. F. (2008). A national survey of guided reading practices: What we can learn from primary teachers. Literacy Research & Instruction, 47(4), 309331. doi:10.1080/19388070802332895 Fountas, I., & Pinnell, G. (1996). Guided reading: Good first teaching for all children. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann. Liang, L., & Galda, L. (2009). Responding and comprehending: Reading with delight and understanding. Reading Teacher, 63(4), 330-333. doi:10.1598/RT.63.4.9 Lloyd, S. (2004). Using comprehension strategies as a springboard for student talk. Journal Of Adolescent And Adult Literacy, 48(2), 114-124. doi:10.1598/JAAL.48.2.3 Marcell, B., DeCleene, J., & Juettner, M. (2010). Caution! Hard hat area! Comprehension under construction: Cementing a foundation of comprehension strategy usage that carries over to independent practice. The Reading Teacher, 63(8), 687-691. doi:10.1598/RT.63.8.8 Mariotti, A. P. (2010). Sustaining students' reading comprehension. Kappa Delta Pi Record, 46(2), 87-89.

14 L. RICHARDS: COMPREHENSION STRATEGY INSTRUCTION Ness, M. (2011). Explicit reading comprehension instruction in elementary classrooms: Teacher use of reading comprehension strategies. Journal of Research in Childhood Education, 25(1), 98-117. doi:10.1080/02568543.2010.531076 Pardo, L. S. (2004). What every teacher needs to know about comprehension. Reading Teacher, 58(3), 272-280. doi:10.1598/RT.58.3.5 Walker, B. J. (2005). Thinking aloud: Struggling readers often require more than a model. Reading Teacher, 58(7), 688-692. doi:10.1598/RT.58.7.10

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (121)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (588)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (400)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5794)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2259)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (345)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (895)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (74)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- ACLS Instr Fac GuideDokumen43 halamanACLS Instr Fac GuideOnek KothaBelum ada peringkat

- Direct Method ApproachDokumen3 halamanDirect Method ApproachKatherine KathleenBelum ada peringkat

- Social and Emotional LearningDokumen22 halamanSocial and Emotional LearningCR Education100% (1)

- Adaptations Planner PDFDokumen4 halamanAdaptations Planner PDFGrade2 CanaryschoolBelum ada peringkat

- PPTDokumen59 halamanPPTsairam saiBelum ada peringkat

- An Index of Teaching & Learning Strategies: 39 Effect Sizes in Ascending OrderDokumen6 halamanAn Index of Teaching & Learning Strategies: 39 Effect Sizes in Ascending OrderterryheickBelum ada peringkat

- Teaching Resume1Dokumen2 halamanTeaching Resume1api-256635688Belum ada peringkat

- Diversity in The Classroom: How Can I Make A Difference?Dokumen47 halamanDiversity in The Classroom: How Can I Make A Difference?hemma89Belum ada peringkat

- Dollar General Literacy Foundation GrantDokumen8 halamanDollar General Literacy Foundation GrantlagreenleeBelum ada peringkat

- Philosophy of Education PaperDokumen6 halamanPhilosophy of Education Paperapi-541765087Belum ada peringkat

- Mercede ResumeDokumen1 halamanMercede Resumeapi-160000915Belum ada peringkat

- MM 320 Organisational Development and ChangeDokumen8 halamanMM 320 Organisational Development and ChangeHQMichelleTanBelum ada peringkat

- Lac-Plan-For-Rpms 2023-2024Dokumen2 halamanLac-Plan-For-Rpms 2023-2024floriejanedBelum ada peringkat

- 2012 Smart Reading Clinic BrochureDokumen2 halaman2012 Smart Reading Clinic BrochureMissy Lanius WallsBelum ada peringkat

- Lesson Plan Template 1-18 2Dokumen6 halamanLesson Plan Template 1-18 2api-378960179Belum ada peringkat

- Tiếng Anh 6 Smart World - Unit 2. SCHOOLDokumen25 halamanTiếng Anh 6 Smart World - Unit 2. SCHOOLHoàng Huy Trần NguyễnBelum ada peringkat

- Chapter 3 Part 2Dokumen8 halamanChapter 3 Part 2Adrian Perolino MonillaBelum ada peringkat

- English Punctuation S Lesson PlanDokumen2 halamanEnglish Punctuation S Lesson PlanjatinBelum ada peringkat

- Faculty Self Appraisal Report PDFDokumen5 halamanFaculty Self Appraisal Report PDFBhavik PrajapatiBelum ada peringkat

- Justification For Scheme of WorkDokumen1 halamanJustification For Scheme of WorkKit SquallBelum ada peringkat

- Constraints On The Development of A Learner-Centered Curriculum: A Case Study of EFL Teacher Education in Viet NamDokumen10 halamanConstraints On The Development of A Learner-Centered Curriculum: A Case Study of EFL Teacher Education in Viet Nambersam05Belum ada peringkat

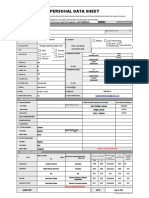

- CS Form No. 212 Personal Data SheetDokumen4 halamanCS Form No. 212 Personal Data SheetCheng ChengBelum ada peringkat

- Introduction To Lesson 1 Module in The Teaching Profession For Printing Copy Copy 2Dokumen19 halamanIntroduction To Lesson 1 Module in The Teaching Profession For Printing Copy Copy 2Iza SagradoBelum ada peringkat

- Russian Math HomeworkDokumen5 halamanRussian Math Homeworktvncsyhlf100% (1)

- LearnEx AcademyDokumen25 halamanLearnEx Academydarshanpanda216Belum ada peringkat

- AnhaltDokumen13 halamanAnhaltBettina TakácsBelum ada peringkat

- An Evaluation of Japan's 2013 Anti-Bullying LawDokumen11 halamanAn Evaluation of Japan's 2013 Anti-Bullying LawCharlotte E. RileyBelum ada peringkat

- Sample Midterm Examination: Ae2 WritingDokumen3 halamanSample Midterm Examination: Ae2 WritingYen Tho NguyenBelum ada peringkat

- ICT C&a Guide Updated eDokumen148 halamanICT C&a Guide Updated eAngelica WenceslaoBelum ada peringkat

- Mentor Teacher Conference Report 2020-2021 1Dokumen2 halamanMentor Teacher Conference Report 2020-2021 1api-510185013Belum ada peringkat