1 s2.0 S0920996401003759 Main

Diunggah oleh

Rizki 'qimel' AmeliaJudul Asli

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

1 s2.0 S0920996401003759 Main

Diunggah oleh

Rizki 'qimel' AmeliaHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Schizophrenia Research 58 (2002) 247 252 www.elsevier.

com/locate/schres

Depressive symptoms at baseline predict fewer negative symptoms at follow-up in patients with first-episode schizophrenia

Piet Oosthuizen a,*, Robin A. Emsley a, Mimi C. Roberts a, Jadri Turner a, Linda Keyter a, Natasha Keyter a, Martijn Torreman b

a

Department of Psychiatry, University of Stellenbosch, P.O. Box 19063, Tygerberg, 7505, Cape Town, South Africa b Janssen-Cilag B.V., Dr. Paul Janssenweg 150, 5026 RH, Tilburg, Netherlands Received 2 September 2001; accepted 12 October 2001

Abstract There is uncertainty regarding the prognostic value of depressive symptoms in schizophrenia, having previously been associated with both favourable and poor outcome. This study investigated the relationship between baseline depressive symptoms and treatment outcome at 6, 12 and 24 weeks in 80 subjects with first-episode schizophrenia or schizophreniform disorder in terms of PANSS total and subscale score changes. No significant association was found between baseline PANSS depression factor scores and PANSS total and subscore changes. However, a significant inverse correlation between baseline depression scores and negative scores at 6, 12 and 24 weeks was found ( p = 0.044, 0.023 and 0.012, respectively). Multiple regression analysis indicated that this finding could not be explained on the basis of age, gender or duration of untreated psychosis. These findings support previous work suggesting that high baseline depressive scores predict favourable outcome. D 2002 Elsevier Science B.V. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Depressive symptoms; Schizophrenia; Prognosis; First episode

1. Introduction Despite the fact that schizophrenia and the mood disorders are generally regarded as separate entities, symptoms of depression are common in patients with schizophrenia. Depending on criteria applied and samples studied, depressive symptoms have been reported to be present in between 7% and 70% of patients with schizophrenia (Birchwood et al., 2001), with a modal prevalence rate of 25% (Siris, 2000).

Corresponding author. E-mail address: pieto@samedical.co.za (P. Oosthuizen).

Previously thought to be uncommon in the acute phase of the illness, it was proposed that the florid symptoms of psychosis may mask depressive symptoms that persist, and are later revealed when the psychosis is successfully treated (Knights and Hirsch, 1981). However, it is now recognized that depressive symptoms are a key feature of the acute psychotic episode, and that the majority of these symptoms resolve with antipsychotic treatment (Koreen et al., 1993). There are various explanations for depressive symptoms in schizophrenia, such as a subjective reaction to the illness and its accompanying adverse life events (Birchwood et al., 1993), substance abuse (Steinberg, 1994), co-morbid major depressive disorder or anxiety

0920-9964/02/$ - see front matter D 2002 Elsevier Science B.V. All rights reserved. PII: S 0 9 2 0 - 9 9 6 4 ( 0 1 ) 0 0 3 7 5 - 9

248

P. Oosthuizen et al. / Schizophrenia Research 58 (2002) 247252

disorders, and neuroleptic-induced dysphoria (Harrow et al., 1994). In the stress diathesis context, depressive symptoms may themselves constitute a stressor that triggers a psychotic episode (Siris, 2000). It has also been suggested that the depressive symptoms experienced in acute psychosis are a core feature of the illness itself (Koreen et al., 1993). There have been conflicting reports regarding the relationship of depressive symptoms to treatment outcome. However, it would appear that their presence in the acute phase of the illness might be associated with a favourable outcome (Kay and Lindenmeyer, 1987), while persistent depressive symptoms appear to be negative prognostic indicators (Falloon et al., 1978; Mandel et al., 1982; McGlashan and Carpenter, 1976). This study examines the relationship between depressive symptoms accompanying the acute phase of first-episode schizophrenia and the response to treatment over a period of 6 months.

were no patients in this study sample who were diagnosed with this disorder. 2.2. Assessment Subjects were assessed by means of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, Patient Edition (SCID-P) (First et al., 1994). In addition, all patients were assessed with the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) (Kay et al., 1987) as well as Clinical Global Impression (CGI) (Guy, 1976). All patients were assessed for side-effects, either with the Extrapyramidal Symptom Rating Scale (ESRS) (Chouinard et al., 1980) (in the case of the RIS-INT35 patients), or with a combination Simpson-Angus Rating Scale (SAS) (Simpson and Angus, 1970), Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (AIMS) (Guy, 1976) and Barnes Akathisia Scale (BAS) (Guy, 1976) (all other patients). A physical examination was also performed. Symptoms were rated by three psychiatrists (PO, JT, LK) who had undergone training and interrater reliability testing for using the PANSS. Ratings were repeated at weekly intervals during the acute treatment phase and then at monthly and later at 3month intervals. PANSS ratings at baseline, 6 weeks, 3 and 6 months were included in the analysis. 2.3. Treatment procedure Patients in the RIS-INT-35 group were treated according to the study protocol. Patients in the open label protocol were treated with an initial dose of haloperidol 1 mg per day which was maintained for 4 weeks, unless there was a significant deterioration in the patients condition. Thereafter, slow upward titration by 1 mg per week was allowed, to a maximum of 10 mg per day. Dose reduction was allowed if side-effects developed. Lorazepam 1 to 2 mg orally or parenterally every 6 h when necessary could be prescribed for additional sedation throughout the study. Orphenadrine and benzhexol were allowed for treatment of extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS). Antidepressant medication was prescribed to patients with persistent, prominent depressive symptoms that did not respond to treatment with a neuroleptic alone. Depressive symptoms were measured by means of the depression factor identified by Kay in his original factor analysis of the PANSS (Kay, 1991). This factor

2. Subjects and method 2.1. Subjects Eighty patients with a first-episode psychosis (DSMIV (American Psychiatric Association, 1994) diagnosis of Schizophrenia or Schizophreniform Disorder) were included in the study. All of these patients form part of an ongoing study of first-episode psychosis by the Department of Psychiatry of the University of Stellenbosch, Cape Town, South Africa. A subset of 40 of these patients were included in the Janssen RIS-INT-35 Futuris Study, and therefore treated in a double-blind, randomized protocol with either low-dose risperidone or low-dose haloperidol. The other 40 patients were treated with low-dose haloperidol in an open protocol. The ethics committee of the University of Stellenbosch approved both studies and all participants provided written, informed consent. Three investigators (PO, JT, LK) were involved in the study, with regular inter-rater reliability training between all raters. Subjects, who were all aged between 18 and 65 years inclusive, had no significant medical conditions and did not meet the criteria for substance abuse. Although Schizoaffective Disorder was not an exclusion criterion for either study, there

P. Oosthuizen et al. / Schizophrenia Research 58 (2002) 247252

249

comprises the composite score for the PANSS items of somatic concern (G1), anxiety (G2), guilt feelings (G3), and depression (G6). Correlations were then sought between the baseline depression factor score and the following PANSS scores at baseline, 6 weeks, 3 and 6 months: PANSS total score, PANSS positive subscale score, PANSS negative subscale score, and composite score (PANSS positive score minus PANSS negative score). When a strong inverse correlation was found with the PANSS negative score, we performed a further analysis to determine if any particular item of the negative subscale of the PANSS was predominantly responsible for the significant inverse association with the baseline depression factor score. We also assessed the association between relapse and mood symptoms at the various time points. Finally, correlations were sought between the baseline depression factor score and gender, age of onset of psychosis, duration of untreated psychosis (DUP) and use of antidepressants throughout the trial.

3. Statistical analysis The Kolmogorov Smirnov test was used to test the significance of departures from normality. Since most of the data did not follow a normal distribution, nonparametric statistical methods were used in the initial univariate analyses. The Mann Whitney U-test was used to compare groups. Spearman rank correlation coefficients for the selected variables were calculated. After testing for normality of the dependent variable, a multiple regression analysis was performed to determine the significance of the relationship between negative symptom scores at follow-up (dependent variable) and baseline depression factor score (independent variable) after adjusting for other factors (age, gender, duration of untreated psychosis). Since the 6-week follow-up negative symptom score distribution was significantly different from normal, only the 12 and 24-week scores were used in this analysis. The significance level was set at 0.05.

4. Results The sample comprised 80 subjects of whom 41 (51%) were male and 39 (49%) were female. The mean

( F standard deviation) age was 27.45 ( F 7.57) years. Although all patients were from the same sample population, the fact that they were treated under two different protocols raised the possibility of significant differences between the two subsets of patients. To evaluate this, the two subsets of patients were compared on the following variables: age, sex, duration of untreated illness, baseline depression factor score, PANSS total mean score at baseline, percentage change in mean between baseline and endpoint of PANSS Total, PANSS positive score, PANSS negative score and composite score at endpoint, as well as dose of medication at each assessment point. There were no significant differences found in any of the parameters, except for dose of medication. As the RIS-INT-35 study was still blinded at the time this paper was written, we assumed, for the purposes of analyses, that 1 mg of risperidone equals 1 mg of haloperidol. Patients included in the RIS-INT-35 study received substantially higher doses of medication than patients in the open label haloperidol study ( p < 0.01). If, however, correlations were sought between dose of medication and outcome measures such as percentage change in PANSS score and subscale scores as well as changes in depression factor scores, no significant correlations were found. The median (and interquartile range) depression factor score on the PANSS was eight (8). Given that the PANSS depression factor identifies depressive symptoms rather than a depressive syndrome (Siris, 2000), we arbitrarily set a definition of caseness as a depression factor score of at least eight, i.e., a score of less than eight was considered as depressive symptoms not being present, and a score of eight or more as being present. Forty-five subjects (56%) met these criteria for caseness at baseline. Baseline depressive symptoms were significantly correlated with female gender ( p = 0.016), but not with age or duration of untreated psychosis. The depression factor score showed a positive correlation with the general psychopathology score (r = 0.4; p = 0.0003), but not with positive symptom score or negative symptom score. However, when the four items of the depression factor were removed from the General Psychopathology Score, this correlation was also no longer significant. There were no significant correlations between baseline depression factor scores and treatment response

250

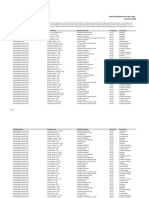

P. Oosthuizen et al. / Schizophrenia Research 58 (2002) 247252 Table 3 Correlations between baseline depression score and individual PANSS negative subscale items (only significant correlations are shown) Weeks 6 12 Factor N2-Emotional withdrawal N4-Passive social withdrawal N2-Emotional withdrawal N3-Poor rapport N6-Lack of spontaneity N7-Stereotyped thinking N2-Emotional withdrawal N3-Poor rapport N4-Passive social withdrawal N6-Lack of spontaneity

*

Table 1 Correlations between depression factor and PANSS negative score (all cases) N Baseline negative score 6-week negative score 12-week negative score 24-week negative score 80 72 67 58 Spearman r 0.07 0.24 0.28 0.33 P-level 0.559 0.044 * 0.023 * 0.012 *

Spearman r 0.25 0.24 0.28 0.31 0.27 0.37 0.28 0.30 0.29 0.36

P-level 0.03 * 0.04 * 0.02 * 0.01 * 0.02 * 0.002 * 0.03 * 0.02 * 0.03 * 0.006 *

* Significance at the 0.05 level. 24

as assessed by reduction in PANSS total scores at 6, 12 and 24 weeks. However, we found a significant inverse correlation between the baseline depression factor score and PANNS negative subscale score from 6 weeks onwards (see Table 1). There was also a significant correlation between the baseline depression factor score and composite score at 24 weeks (r = 0.35; p = 0.007). Exclusion of non-completers at 24 weeks did not influence the results significantly (Table 2) and made the correlation with the composite score even more pronounced (r = 0.43; p = 0.001). Patients were then stratified into two groups with either high (over eight) or low (less than eight) depression factor scores. We found a significant difference in composite score between the two groups at 6, 12 and 24 weeks ( p = 0.04; p = 0.049; p = 0.011; respectively) with patients in the high score group less likely to have a negative composite score. Because it could be argued that one specific item of the negative subscale could be responsible for the association between the baseline depression factor score and negative subscale scores, correlations were sought between individual items on the PANSS negative subscale and the baseline depression factor score. As shown in Table 3, there was a significant inverse correlation with emotional withdrawal at each assessment point. Also, progressively more items showed the

Significance at the 0.05 level.

Table 2 Correlations between depression factor and PANSS negative score (excluding non-completers) N Baseline negative score 6-week negative score 12-week negative score 24-week negative score

*

same significant inverse correlation with baseline depressive symptoms at each assessment point. To assess the contributions of age, gender, depression factor score and duration of untreated psychosis to predicting negative symptoms, multiple regression analysis was performed with PANSS negative subscale score at 12 and 24 weeks as the dependent variable and the other variables as predictor variables. The baseline depression factor was the only independent variable to be significantly related to the negative subscale score, both at 12 weeks (R2 = 0.1; p = 0.17; F(4,62) = 1.68; standard error of estimate = 5.22; p = 0.043) and 24 weeks (R2 = 0.14; p = 0.09; F(4,53) = 2.12; Standard error of estimate = 6.04; p = 0.039). (However, the relatively low R2 obtained in the regression analysis indicates that baseline depression factor scores can explain only a small proportion of the variation in negative symptoms at follow-up.) Antidepressant medication was prescribed for persistent, prominent depressive symptoms as follows: At 6 weeks, 2 of 68 patients; at 12 weeks, 3 of 67 patients; and at 24 weeks 10 of 58 patients. Patients who received antidepressants had significantly lower baseline negative subscale scores (n = 10; median = 19; IQR = 9) than those who were not placed on antidepressants (n = 48; median = 25.5; IQR = 10; p = 0.036).

Spearman r 0.034 0.264 0.309 0.329

P-level 0.802 0.045 * 0.018 * 0.007 *

58 58 58 58

5. Discussion In keeping with previous studies, we found depressive symptoms to be common in first-episode psy-

Significance at the 0.05 level.

P. Oosthuizen et al. / Schizophrenia Research 58 (2002) 247252

251

chosis (56% at baseline in this sample) and particularly in female patients (Birchwood et al., 2001; Emsley et al., 1999; Falloon et al., 1978). The median baseline score for the PANSS depression factor was consistent with what we previously found in firstepisode schizophrenia (Emsley et al., 1999). This once again does not support the notion that depression is only revealed once the psychosis remits (Knights and Hirsch, 1981), as depressive symptoms were prominent at the outset and diminished substantially as the psychotic symptoms improved. Also, our findings argue against the likelihood that depressive symptoms in schizophrenia are misdiagnosed negative symptoms (Tollefson et al., 1998)in which case a significant association between negative and depressive symptoms would have been expected. Finally, the baseline depressive symptoms identified in our sample are unlikely to be related to any pharmacological treatment or its side effects (De Arlacon and Carney, 1969), as the majority of subjects were medication-naive on entry to the study. The lack of a significant association between depression scores and positive symptoms in our study is surprising, given the fact that such an association has often been reported (Emsley et al., 1999; Koreen et al., 1993; Lysaker et al., 1995; Norman and Malla, 1994). The reasons for our failure to demonstrate such an association are not immediately apparent, as these symptoms are thought to co-occur in acute psychosis, and simultaneously improve with successful antipsychotic therapy (Koreen et al., 1993). Recent work indicates, however, that depressive symptoms may also emerge independent of positive symptoms. In a 12month prospective study of 105 subjects with schizophrenia, two course patterns of depressive symptoms were identifiedthose following the same course as positive symptoms during psychotic episodes, and those emerging de novo without a change in positive symptoms (Birchwood et al., 2001). The lack of a significant association between baseline depressive scores and baseline negative scores is consistent with most previous studies suggesting that depressive symptoms and negative symptoms are relatively independent of one another (Emsley et al., 1999; Lysaker et al., 1995; Norman and Malla, 1994), although Koreen et al. (1993) reported a significant correlation between depression and both positive and negative symptoms.

The present study failed to find any association between baseline depressive symptoms and treatment outcome in terms of PANSS symptom reduction. However, it does identify a previously unreported inverse relationship between acute depressive symptoms and persistent negative symptoms, i.e., higher acute depression scores being predictive of fewer negative symptoms later on. These findings cannot be explained by age or gender differences, duration of untreated psychosis, or effects due to drop-outs, since correlations remained significant even after taking these variables into account. Thus, although higher baseline depression scores did not predict better outcome in terms of greater reduction of PANSS total and subscale scores, our findings do suggest that the presence of depressive symptoms in the acute psychotic phase of the illness is a favourable prognostic indicator, given the well-established association between negative symptoms and poor overall outcome (Eaton et al., 1995; The Scottish Schizophrenia Research Group, 1988). In a recent study (Lancon et al., 2001), investigating relationships between depression and psychotic symptoms over the course of the illness, it was found that depressive symptoms in the acute phase were associated with positive symptoms only. However, depressive symptoms in the stable phase, in addition to being associated with positive symptoms, showed a positive correlation with negative symptoms. This finding, taken together with the results of our study, provides compelling evidence that symptoms of depression in the acute phase predict favourable outcome, while symptoms of depression that persist or emerge after the acute phase are predictive of poor outcome. Our findings are in keeping with the theory of symptom dimensions in psychosis as proposed by Shergill et al. (1999). According to these authors, a clear dichotomy between schizophrenia and mood disorders does not exist. Rather, the aetiology of psychosis can be explained by the interactive effects of two major types of risk factors; first, those conferring neurodevelopmental impairment and second, a genetic predisposition to react to adverse life events by developing psychotic symptoms. Mood symptoms tend to be more prominent at the life events/genetic predisposition end of the spectrum, and therefore, are presumably associated with a more favourable outcome. Conversely, negative symptoms are associated with neurodevelopmental impairment, and therefore poorer outcome. Our data support

252

P. Oosthuizen et al. / Schizophrenia Research 58 (2002) 247252 Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, Patient edn. (SCID-P), Version 2. New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research, New York. Guy, W., 1976. ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology: Publication ADM 76-338. US Department of Health, Education and Welfare, Rockville, MD. Harrow, M., Yonan, C.A., Sands, J.R., Marengo, J., 1994. Depression in schizophrenia: are neuroleptics, akinesia, or anhedonia involved? Schizophr. Bull. 20, 327 338. Kay, S.R., 1991. Positive and Negative Syndromes in Schizophrenia: Assessment and Research. Brunner/Mazel, New York. Kay, S.R., Lindenmeyer, J., 1987. Outcome predictors in acute schizophrenia: Prospective significance of background and clinical dimensions. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 175, 152 160. Kay, S.R., Fizbein, A., Opler, L.A., 1987. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 13, 261 267. Knights, A., Hirsch, S.R., 1981. Revealed depression and drug treatment for schizophrenia. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 38, 806 811. Koreen, A.R., Siris, S.G., Chakos, M., Alvir, J.M., Mayerhoff, D., Lieberman, J.A., 1993. Depression in first-episode schizophrenia. Am. J. Psychiatry 150, 1643 1648. Lancon, C., Auquier, P., Reine, G., Bernard, D., Addington, D., 2001. Relationships between depression and psychotic symptoms of schizophrenia during an acute episode and stable period. Schizophr. Res. 47, 135 140. Lysaker, P.H., Bell, M.D., Bioty, S.M., Zito, W.S., 1995. The frequency of associations between positive and negative symptoms and dysphoria in schizophrenia. Compr. Psychiatry 36, 113 117. Mandel, M.R., Severe, J.B., Schooler, N.R., Gelenberg, A.J., Mieske, M., 1982. Development and prediction of postpsychotic depression in neuroleptic-treated schizophrenics. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 39, 197 203. McGlashan, T.H., Carpenter, W.T., 1976. An investigation of the post-psychotic depression syndrome. Am. J. Psychiatry 133, 14 19. Norman, R.M.G., Malla, A.K., 1994. Correlation over time between dysphoric mood and symptomatology in schizophrenia. Compr. Psychiatry 35, 34 38. Shergill, S.S., van Os, J., Murray, R.M., 1999. Schizophrenia and depression: what is their relationship? In: Keck, P.E.J. (Ed.), Managing the Depressive Symptoms of Schizophrenia. Science Press, London, pp. 12 29. Simpson, G.M., Angus, J.W.S., 1970. A rating scale for extrapyramidal side effects. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 212, 11 19. Siris, S.G., 2000. Depression in schizophrenia: perspective in the era of atypical antipsychotic agents. Am. J. Psychiatry 157, 1379 1389. Steinberg, J.R., 1994. Substance abuse and psychosis. In: Ancill, R.J., Holliday, S., Higenbottom, J. (Eds.), Schizophrenia. Exploring the Spectrum of Psychosis. Wiley, Chichester, pp. 259 289. The Scottish Schizophrenia Research Group, 1988. The Scottish First Episode Schizophrenia Study: V. One-year follow-up. Br. J. Psychiatry 152, 470 476. Tollefson, G.D., Sanger, T.M., Lu, Y., Thieme, M.E., 1998. Depressive signs and symptoms in schizophrenia. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 55, 250 258.

this inverse relation between depressive symptoms and negative symptoms and provide a possible explanation for the previously reported positive prognostic effect of depressive symptoms in acute psychosis. In conclusion, we can thus say that patients present with depressive symptoms and signs at the first episode will have a milder course in terms of negative symptoms, at least over the first 6 months. The fact that this correlation was not found at baseline may reflect the masking of negative symptoms in the storm of positive and disorganization symptoms at the onset of illness.

Acknowledgements This work was supported by the Medical Research Council of South Africa, and the Harry and Doris Crossley Fund. The RIS-INT-35 Study is sponsored by the Janssen Research Foundation, which has also offered statistical and review support in the analyses of the data.

References

American Psychiatric Association, 1994. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Psychiatric Disorders, IV. American Psychiatric Press, Washington. Birchwood, M., Mason, R., Macmillan, F., Healy, J., 1993. Depression, demoralization and control over psychotic illness: a comparison of depressed and non-depressed patients with a chronic psychosis. Psychol. Med. 23, 387 395. Birchwood, M., Iqbal, Z., Chadwick, P., Trower, P., 2001. Cognitive approach to depression and suicidal thinking in psychosis: I. Ontogeny of post-psychotic depression. Br. J. Psychiatry 177, 516 521. Chouinard, G., Ross-Canard, A., Annable, L., Jones, B.D., 1980. The extrapyramidal symptom rating scale. Can. J. Neurol. Sci. 7, 233. De Arlacon, R., Carney, M.P., 1969. Severe depressive mood changes following slow release intramuscular fluphenazine injections. Br. Med. J. 3, 564 567. Eaton, W., Thara, R., Federman, B., Melton, B., Liang, K.-Y., 1995. Structure and course of positive and negative symptoms in schizophrenia. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 52, 127 134. Emsley, R.A., Oosthuizen, P.P., Joubert, A.F., Roberts, M.C., Stein, D.J., 1999. Depressive and anxiety symptoms in patients with schizophrenia and schizophreniform disorder. J. Clin. Psychiatry 60, 747 751. Falloon, I., Watt, D.C., Shepherd, M., 1978. A comparative controlled trial of pimozide and fluphenazine decanoate in the continuation therapy of schizophrenia. Psychol. Med. 8, 59 70. First, M.B., Spitzer, R.L., Gibbon, M., Williams, J.B.W., 1994.

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (895)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (266)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (400)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (74)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (345)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2259)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)

- TX Hosp Based Prac List 120120Dokumen975 halamanTX Hosp Based Prac List 120120David SantosBelum ada peringkat

- Daftar Pustaka: ND NDDokumen1 halamanDaftar Pustaka: ND NDCherylina GraceBelum ada peringkat

- Respiratory MCQDokumen24 halamanRespiratory MCQfrabziBelum ada peringkat

- ASPAK Alkes IGDDokumen2 halamanASPAK Alkes IGDAdra AdeBelum ada peringkat

- WHO - Weekly Epidemiological Update On COVID-19 - 22 February 2022Dokumen26 halamanWHO - Weekly Epidemiological Update On COVID-19 - 22 February 2022Adam ForgieBelum ada peringkat

- Overview of Anesthesia - UpToDateDokumen11 halamanOverview of Anesthesia - UpToDateFernandoVianaBelum ada peringkat

- Sean Benesh Resume 10-1-23Dokumen2 halamanSean Benesh Resume 10-1-23api-708800698Belum ada peringkat

- Public Health Approaches To Malaria: Source: National Library of MedicineDokumen24 halamanPublic Health Approaches To Malaria: Source: National Library of MedicineRahmalia Fitri RosaBelum ada peringkat

- The Icd - 10 DictionaryDokumen10 halamanThe Icd - 10 DictionarySeraphin MulambaBelum ada peringkat

- Nursing Theory FlorenceDokumen19 halamanNursing Theory FlorencesrinivasanaBelum ada peringkat

- DafpusDokumen4 halamanDafpusSyarifah Aini KhairunisaBelum ada peringkat

- CHN MidtermDokumen119 halamanCHN MidtermAbellon Maria PaulaBelum ada peringkat

- An Introduction To Tuberous Sclerosis ComplexDokumen20 halamanAn Introduction To Tuberous Sclerosis ComplexArif KurniadiBelum ada peringkat

- AcuteExpertSystem PDFDokumen3 halamanAcuteExpertSystem PDFMMHMOONBelum ada peringkat

- Apollo Hospitals FinalDokumen19 halamanApollo Hospitals Finalakash_shah_42Belum ada peringkat

- Case-Presentation OTITIS MEDIADokumen22 halamanCase-Presentation OTITIS MEDIAJean nicole GaribayBelum ada peringkat

- Stress WorkshopDokumen14 halamanStress Workshopapi-297796125Belum ada peringkat

- Treatment Planning 01Dokumen43 halamanTreatment Planning 01Amr MuhammedBelum ada peringkat

- DisabilityDokumen450 halamanDisabilityTony Kelbrat100% (1)

- Annual Meeting Program: CollaboratingDokumen330 halamanAnnual Meeting Program: CollaboratingSouhaila AkrikezBelum ada peringkat

- Strategic Plan ProposalDokumen27 halamanStrategic Plan ProposalMaya Fahel LubisBelum ada peringkat

- Haemodialysis Access UKDokumen19 halamanHaemodialysis Access UKmadimadi11Belum ada peringkat

- Ethics and Mental HealthDokumen15 halamanEthics and Mental Healthapi-3704513100% (1)

- Gloclav Eng Insert Oct 06 PDFDokumen4 halamanGloclav Eng Insert Oct 06 PDFbobkakaBelum ada peringkat

- Sensimatic 600SE User ManualDokumen8 halamanSensimatic 600SE User ManualduesenBelum ada peringkat

- Tangcay Tenorio. Teves Group 4 C1 Concept Map On Hydatidiform MoleDokumen11 halamanTangcay Tenorio. Teves Group 4 C1 Concept Map On Hydatidiform MoleJoi Owen TevesBelum ada peringkat

- 10 Squamouspapilloma-ReportoftwocasesDokumen7 halaman10 Squamouspapilloma-ReportoftwocasesAyik DarkerThan BlackBelum ada peringkat

- (JURNAL, Eng) A Retrospective Cohort Review of Prescribing in Hospitalised Patients With Heart Failure Using Beers Criteria and STOPP RecommendationsDokumen7 halaman(JURNAL, Eng) A Retrospective Cohort Review of Prescribing in Hospitalised Patients With Heart Failure Using Beers Criteria and STOPP RecommendationsAurellia Annisa WulandariBelum ada peringkat

- (RADIO 250) LEC 09 Basic Ultrasound PDFDokumen9 halaman(RADIO 250) LEC 09 Basic Ultrasound PDFSharifa AbdulghaffarBelum ada peringkat

- Draw Cardiac Arrest Algorithm (Aha)Dokumen21 halamanDraw Cardiac Arrest Algorithm (Aha)Thanyun YunBelum ada peringkat