William Davidson Institute - Case Study

Diunggah oleh

Daksh SethiHak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

William Davidson Institute - Case Study

Diunggah oleh

Daksh SethiHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

December 30, 2009

case 1-428-987

Bringing Safe Water to Indias Villages and Communities: The Naandi Foundation

A recent survey of national opinion revealed that when asked what would make respondents proud of India, a staggering 73% said that availability of safe drinking water to all our people would truly make them proud of being an Indian Indian Prime Minister Dr. Manmohan Singh

1

Water and Poverty

India suffers a particularly large health burden due to poor water quality. The WHOs Safe Water, Better Health report in 2008 suggested that 780,000 deaths in India are directly a result of poor water and 4 sanitation . Diarrhea alone causes more than 1,600 deaths each daymore than any other disease. It is estimated that 37.7 million Indians are affected by waterborne diseases annually and 73 million working days are lost due to waterborne disease each year. WaterAid estimates an economic burden of $600 million

Published by GlobaLens, a division of the William Davidson Institute at the University of Michigan. 2010 William Davidson Institute. This case was written by Josh Katz and Sheel Mahnat under the supervision of Allen Hammond with Jim Koch and Sherill Dale as the basis for class discussion rather than to illustrate either effective or ineffective handling of an administrative situation. This case study was supported by a generous grant from the Skoll Foundation.

Unauthorized reproduction and distribution is an infringement of copyright. Please contact us for permissions: Permissions@GlobaLens.com or 734-615-9553.

DO

According to the World Water Development Report (WWDR), problems of poverty are, on most occasions, inextricably linked with those of water its availability, its proximity, its quantity, and its quality. Worldwide, over 1 billion people lack access to a reliable supply of clean water. The problem is especially acute in the developing world, with waterborne ailments accounting for 80% of disease and deaths and an estimated 2 2% drag on developing countries GDP . It is beyond debate that improving the access of poor people to safe water has the potential to make a major contribution toward poverty eradication. In fact, access to 3 clean water has factored into each of the eight United Nations Millennium Development Goals , and top technologists have begun searching for improved technological solutions.

NO T

In 2002, Dr. K. Anji Reddy, Naandis chairman and founder, was staying at the Imperial Hotel in Tokyo when he was struck by the sight of a sign that said, simply: the tap water in this toilet is potable. He then came back to India and found the same sign at an Oberoi property in India. Realizing that the affluent people of India have access to clean and drinkable water even in the toilet, yet the majority of Indias public health expenditure goes to treating waterborne diseases, Dr. Reddy became determined to bring safe drinking water to Indias villages. As a doctor and a farmers son, Dr. Reddy was also acutely aware how many problems stem from unsafe water.

CO PY

Bringing Safe Water to Indias Villages and Communities: The Naandi Foundation

1-428-987

in India each year. The Indian constitution proclaims safe water as a fundamental right of its citizenry, yet provides no explicit provision for making that right a reality for the majority. As Indias population and wealth (and per capita water demand) grow so will the strain on the countrys natural resources and infrastructure. According to a 2006 World Bank report, by 2020 Indias water demand 5 will exceed all sources of its supply . Exacerbating this problem is water pricing. Where piped water is available, it is significantly underpriced, far below both developed and developing country prices. Where not piped, pricing can fall on the other end of the spectrum with monopolistic practices, greed, and corruption 6 playing an additional role.

History of Water Development Policy

As early as the 16th century, philosopher Sir Francis Bacon wrote extensively about desalination in his compilation A Natural History of Ten Centuries. He mentioned that seawater could be purified if allowed to percolate through sand, though sand filtration was not utilized successfully until the 17th century when Italian physician Lucas Antonius Portius desalinated water with three pairs of sand filters. Municipal water treatment began in Scotland and England in the early 1800s. Slow sand filtration was the primary method used in these early water treatment plants, eventually adding charcoal filtration to improve taste. In places where these slow sand filters were used around London, officials noticed a decrease in cholera deaths during the epidemics of 1849 and 1853, the first established relationship between clean drinking water and health. After London officials realized contaminated water had been the culprit in these disease outbreaks, London enacted the Metropolitan Water Act of 1852, which required the filtration of all water supplied to the London area. This legislation is one of the first instances of government regulation of a water supply. As municipal water treatment facilities sought to increase the quality and healthfulness of public water supplies, more and more cities began to implement chlorine into their water treatment process. 8 This application of chlorine resulted in a sharp decline in deaths from typhoid as well. After the tremendous success of drinking water chlorination in England, chlorination was instituted in New Jersey and soon spread through the entire United States. Chlorination of drinking water, combined with the use of sand water filters, resulted in the virtual elimination of such waterborne diseases as cholera, typhoid, and dysentery in the developed world. Chlorine was so effective at eliminating the outbreak and spread of waterborne diseases that Life magazine in 1997 named water chlorination as probably the most 9 significant public health advance of the millennium. Safe drinking water came on the agenda of multilateral institutions in the 1950s and 1960s, after the decolonization period created government-owned boards for several sectors including agriculture, water, power, and utilities. The multilateral institutions provided funding and loans for capital-intensive projects such as trunk sewers, water pipes, large-scale irrigation, large dams, and river basin development in developing nations. In the 1970s, the World Bank began to make serious efforts in expanding water development to rural areas. In a 1973 speech to the Board of Governors of the World Bank, Robert McNamara said: The basic problem of poverty and growth in the developing world can be stated very simply. The

2

DO

NO T

CO PY

The desire for pure drinking water is not a modern phenomenon. Nomadic tribes based their entire life around following water supplies, and the father of medicine, Hippocrates, invented Hippocrates sleeve, which was a cloth bag and used for water purification, which was helpful in removing hardness and bad odors from the water. The Greeks and Romans too developed various methods for treating water in order to 7 control tastes and odor.

Bringing Safe Water to Indias Villages and Communities: The Naandi Foundation

1-428-987

growth is not equitably reaching the poor. And the poor are not significantly contributing to growth. Development of major irrigation works is not enough. Too many small farmers would be left unaffected. 10 Tube-wells, low-lift pumps, and small dams can make major contributions to productivity. The UN and World Bank began supporting the use of pumps to give rural areas access to groundwater, and began projects to dig tube-wells around the world. Millions of tube-wells were dug in Bangladesh and West Bengal, India, financed by UNICEF and the World Bank in an effort to provide enough water for 11 agricultural purposes and to combat poor quality surface drinking water that was causing fatal diarrhea. In 1976, the UN Decade for Women was declared, and access to safe drinking water was a part of the declaration. In 1977, the UN held its first conference on water, in Mar del Plata, Argentina. At the conference, the UN officially recognized water as both a human right and a basic need that requires economic instruments for efficiency. The 1980s were declared the UN Drinking Water Supply and Sanitation Decade with an initial goal of providing every person with access to water of safe quality and adequate 12 quantity, along with basic sanitary facilities, by 1990. During the decade, the proportion of households with access to drinking water rose from 38% to 66% in Southeast Asia, from 66% to 79% in Latin America, and from 32% to 45% in Africa. In total, during the International Drinking Water Supply and Sanitation Decade (1981-1990), an additional 1.2 billion people gained access to safe water, and about 770 million to adequate sanitation. This trend continued into the 1990s and by 1994 an additional 780 million gained 13 access to water. In the 1990s, it was found that the wells dug by the UN and World Bank in Bangladesh were dug without testing for metal impurities in the environment, as the tests were not mandatory until years later and the wells became contaminated with arsenic. Around 75 million people were exposed to arsenic-laden 14 water and 200,000 to 270,000 deaths from cancer will be seen in the future, thought to be the worst mass poisoning in history. This had an effect on development, as it was realized that hand-pump water is not necessarily safe, and new methods were needed to tackle the issue of safe drinking water. The United Nations again addressed the topic in the 1992 Report of the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development, in Rio de Janeiro. Participants affirmed the need to develop environmentally tailored legislation that would aid in human development, extending to water management. This is where the UN and World Bank began to diverge. The World Banks stated goal is a strategy based on sustainable water resources management. It realized that the governments and international aid agencies could not maintain the millions of hand-pumps around the world, and made a shift in thinking toward market-oriented reforms, decentralization, and disengagement of state infrastructure/privatization. The UN and the World Bank continue to see water differently. The UN sees water as a basic human right vs. the World Banks view of water as an economic good. In that manner, the World Bank has significantly encouraged privatization of water facilities, even making it a requirement for new loans under the structural adjustment programs. Current thinking is relatively balanced regarding public versus private provisions (both are accepted as long as they are efficient and recover costs). However, the past 20 years has seen massive growth in private investment into safe drinking water, and governments are increasingly ceding control of water, either through partial or full divestures, management contracts, or Build Operate Transfer schemes. Despite the significant gains in private interest in water, investment remains far below that made in other private infrastructure needs (see Exhibit 14). Although commercial approaches to water treatment have been on the rise, commercial urban-scaled water treatment facilities have encountered many difficulties in reaching beyond the city limits and into rural areas, where many of the worlds poor reside. On the other end of the spectrum are point-of-use water

3

DO

NO T

CO PY

Bringing Safe Water to Indias Villages and Communities: The Naandi Foundation

1-428-987

systems, designed to serve an individual or household. Technologies such as the LifeStraw portable purifier 15 and sachet-based purification tables have gained some traction. For consistent use, those technologies are yet to prove cost-effective, and there remain significant distribution challenges for both the devices as well as the replacement filters. A new wave of social entrepreneurs is tackling the problem at an in-between, community scale, with products and services aimed to fulfill the needs of a community or village. Their efforts in bringing down technology-related costs, working closely with local governments and with communities to influence the way they relate to this resource, have resulted in willingness to pay for clean water even in very poor communities, as experiences in India and rural Africa have shown. Naandi is a leader in this space. (For a summary of the three models of clean water filtration and distribution, along with pros and cons, see Exhibit 15.)

The Naandi Foundation

Naandis ultimate vision is eradicating poverty. The Naandi Foundation, a nonprofit organization, was founded in 1998 by Mr. Chandrababu Naidu, then chief minister of Andhra Pradesh province, with Dr. Anji Reddy, the driving force behind Dr. Reddy Labs, a NYSE-listed pharmaceutical company, as its cofounder and chairman. Naandi, which means new beginning in Sanskrit, has developmental efforts in three sectors: child rights, safe drinking water, and sustainable livelihoods. Naandis ideology revolves around building sustainable models within the social sector that deliver critical services efficiently and equitably to underserved communities. Naandi works together with governments, communities, corporate entities and NGOs to channel their financial, technical, and human capital resources. The aim is to create sustainable, yet affordable, public-private partnership models to create new approaches to solve widespread poverty-related issues across the country by making efficient use of funds. While a nonprofit by its constitution, Naandi is run like a corporation with business principles in mind. Its chief operating officer, Amit Jain, maintains an entrepreneurial environment and has spearheaded efforts to establish business processes through the documenting of standard operating procedures and the consistent measurement of impact and results. Naandi is guided and overseen by a very prominent Board of Trustees that includes Mr. Anand Mahindra, the vice chairman of one of Indias largest automobile, farm equipment, and infrastructure companies; Dr. Isher Judge Ahluwalia, a leading Indian development economist; Mr. Rajendra Prasad, chairman of Soma Enterprises, a leading infrastructure firm with a number of public-private partnership projects; and Dr. Chiranjeevi, a renowned Telugu film star.

Naandi Safe Water Program

Water provision in India is the mandate of state governments and is often perceived by the general public as a public responsibility. Despite the general failure of the public sector to provide quality services, the high level of government intervention and control and the political risks associated with the sector have led few private players to step in and fill the gap. Private initiatives have focused on household-level products for middle- and high-income urban households, such as with Eureka Forbes and its Aquasure filters. The few players working to provide safe water at the community level have primarily focused on commercial segments and have struggled to attract professional talent and funding. The Naandi Safe Water Program was created in 2006, aiming to encourage villagers to drink and use clean water daily. The partnership between Naandi Foundation and US-based Water Health International that began in 2006 was a turning point. Focusing on the underserved, they developed a replicable design for

4

DO

NO T

CO PY

Bringing Safe Water to Indias Villages and Communities: The Naandi Foundation

1-428-987

water plants and identified a viable PPP model combining their own funding, donations, and contributions by local communities. The provision of safe water has several recognized health and societal benefits, including improved daily productivity, minimized time lost by illness, and overall improvement of the immediate and long term health prospects of communities. The Naandi model integrates the purification and distribution of chemical-free and pathogen-free water with education on health and hygiene. Naandi develops a community-scale water treatment whereby villages each have a clean water point where municipal water is cleaned using either reverse osmosis (with Tata Projects, Malthe Winje Norway, and Permionics India as technical partners) or UV technology (with WaterHealth India as technical partner), and then sold to customers at very affordable prices through a subscription model. The subscription model ensures that customers use safe water daily, reducing the risk that they will mix contaminated water with their clean water. By not allowing customers to buy single servings or small quantities, Naandis subscription model nudges consumers to consistently use clean water and therefore gain the benefits of using safe water. Naandi identifies villages based on various factors such as demography, purchasing power of the villagers, quality of current water available to the villagers, health epidemics in the village, and the availability of support (financial and non-financial) from the community and other donors. Naandi has dubbed its model The Tripartite Partnership Model, with the Gram Panchayat (the village council) and donor primarily providing the physical assets except for the technology, Naandi leading promotion, distribution, and education, and a technical partner providing technology, maintenance, and quality assurance. The community must support Naandis efforts, providing water, land, and general support. Technology, quality assurance, and, in some cases, financing, come from private sector partners. Naandi coordinates all parties while also mobilizing the community and external funding sources, and uses its expertise in social marketing to ensure that community members subscribe. Key for this model to work is an effective relationship with the local village governing body, called the Gram Panchayat in India. The Gram Panchayat officials, headed by the Sarpanch, are elected every five years. In the Naandi model, the Panchayat is responsible for providing Naandi with land to set up the water treatment unit and distribution center, access to a local water source, and access to electricity. In exchange, Naandi will not only provide safe, clean water at affordable prices but, in some states, will actually turn over the business to the Gram Panchayat after five to seven years. Maintaining positive relations and providing a financial incentive to the Gram Panchayat are essential factors in enabling Naandi to scale at such a pace. The unit draws water from the local water resource, purifies it of contaminants and offers it to households 16 at a fee of 0.1 rupee (0.2 cents) per liter, typically in increments of 20 liters per day. Villagers purchase 17 monthly subscription cards that entitle them to 20 liters of clean water every day, for 60 rupees. Customers must bring their own container, which they fill at one of the taps (typically six-eight) located on the outside of the Naandi building. Initially at floor level, the taps and receptacle platform are now raised off the ground, an adjustment made after observation and customer feedback reported difficulty in filling and lifting the container. The majority of customers arrive by bicycles and motorbikes. Naandi encourages the use of food-grade 20-liter jerry cans, which Naandi also sells to customers at cost (~150 rupees). In some cases, Naandi will offer an installment payment plan for the jerry can to ease the upfront cash requirement. The fee charged to fill water makes the project sustainable, as all maintenance and servicing of the plant, including the salary of the staff (plant operator and safe water promoter, both recruited from the village), 18 are covered by the revenues of the project.

5

DO

NO T

CO PY

Bringing Safe Water to Indias Villages and Communities: The Naandi Foundation

1-428-987

The model would not be successful simply by offering safe drinking water at affordable rates. To create a long-term reduction in exposure to environmental risks that lead to waterborne diseases, it is essential to market the importance of safe water. To that end, Naandi creates intensive campaigns on health and personal hygiene to educate rural communities on the need to store water carefully, adopt hygienic sanitation practices and avoid contaminating water resources. This helps to influence conventional rural mindsets to adopt safe water and creates demand from villages/Panchayats to implement the Safe Water Program for their villages. Each plant employs a safe water promoter (SWP), typically a woman from the village community, who ensures that villagers are made aware of the plant and service (see Exhibit 11.2 for FAQ) and who encourages them to make the transition to safe drinking water. The SWP is also responsible for promoting hygienic sanitation practices among villagers through an Information, Education, and Communication campaign (IEC). Experimentation and Innovation at Naandi Experimentation is a deliberate piece of the culture that COO Amit Jain has instilled. He has developed a charged up environment, that backs experimenters ensuring against failure. The jerry can Refining the jerry can has been an ongoing project for Naandi since the inception of the clean water initiative. Naandis jerry can is designed such that cups or ladles cannot easily be dipped in the vessel, reducing the risk of contamination. The 20-liter size is also deliberately heavy enough that men are more likely to collect the water, reducing the burden on village women. However, the current rectangular design with a built-in handle is being refined. Villagers have found that it is not shaped comfortably to be carried or used in the home. Naandi has partnered with IDEO, the San Franciscobased design firm, to pilot a newly redesigned jerry can called the whistle, so named because of its shape. RFID Remote Site Naandi also encourages experimentation with improvements among its operators and staff. For example, in June 2009, a pilot site was launched in Punjab that uses RFID-based cards to dispense water. This remote site, located more than one kilometer away from a water purification plant, will eventually automatically dispense water to customers without the need of an operator present. Customers will add credit to their smart card in the same one-month allotments and scan the card at the remote site, which will automatically dispense water. The site contains a 2,000-liter storage tank that is filled daily from a vehicle that brings water from the nearby plant. The project was initiated in partnership with US-based Acumen Fund, a nonprofit global venture fund that uses entrepreneurial approaches to solve the problems of global poverty. Delivery In evaluating why villagers are not subscribers to the Safe Water Program, Naandi has found that the pickup from the water point is the primary reason for not subscribing. In some villages, Naandi has established relationships with locals to deliver the water to subscribers. By becoming Naandi deliverers, the drivers are able to increase usage of their autorickshaws (or other transportation vehicles) and supplement their income. Customers are typically charged between two and three rupees for delivery.

19

DO

NO T

6

CO PY

Bringing Safe Water to Indias Villages and Communities: The Naandi Foundation

1-428-987

Achieving Scale

Naandi has consistently surpassed its aggressive growth targets. To achieve and continue this trajectory, Amit Jain, COO, points to four attributes required for scale. First, an organizational structure that supports growth yet continues to allow for experimentation and the sharing of best practices including a strong performance review mechanism (See Exhibit 5 for a complete organizational chart). Second, Naandis constantly refined marketing effort implemented by experienced rural marketers continues to expand the customer base and improve penetration. Third, by enhancing Naandis visibility through partnerships (technical and non-technical) and public relations, the Safe Water Program is able to expand its partner and funding base. Fourth, by proving the concept that community-scale drinking water at affordable subscription rates can be successful, Naandi is able to expand its relationship with the public sector. As Naandi considers expansion to additional states, positive relationships and success stories will be essential to gain favor with new public sector partners.

Technology

There are three types of contaminants that Naandi seeks to eliminate to create safe water: Bacterial: pathogens, viruses, and microorganisms not seen by the eye Chemical: fluoride, dissolved solids, nitrates, sulfates, pH, odor, color Biological: visible organisms carcasses, flies, etc.

The technologies commonly used to deal with these contaminants are ultraviolet (UV), ultra filtration (UF), nano-filtration, and reverse osmosis (RO), and each presents a unique set of advantages. Each of them handles biological contamination and they have varying levels of success with filtering out bacterial and chemical contaminants. Ultraviolet completely filters out bacterial contaminants but does not address the chemical contaminants, making it suitable for areas where bacterial contamination is of greatest concern. Ultraviolet light inactivates the microorganisms in the water, freeing it of pathogen contamination. UF takes care of both bacterial and chemical contaminants, though it fails to fully address the total dissolved solids. Nano-filtration is not as commercially developed, though it may emerge as the future of water filtration. Reverse osmosis technology addresses both bacterial and chemical contaminants, though it has higher up-front and maintenance costs than most ultraviolet systems. At the outset of the Safe Water Program, Naandi exclusively partnered with WaterHealth International and deployed its ultraviolet technology systems. The technology was first piloted in 2005 in the Bomminampadu village in the coastal Krishna district of Andhra Pradesh. The village had a history of waterborne diseases and contaminated water-linked debilities, and for generations, residents of the village have been dependant

7

DO

NO T

Naandis mission is to provide safe drinking water to as many people as possible, and to that end, the organization is technology neutral, and has experimented with different technologies in different areas in an aim to provide the most appropriate technology at the best price.

CO PY

Bringing Safe Water to Indias Villages and Communities: The Naandi Foundation

1-428-987

on pathogen-contaminated village water sources such as wells, tanks, and canals. The UV technology supplied by WaterHealth allows the villagers access to drinking water that is 99.9% bacteria free. As Naandi began to expand away from the coastal region of Andhra Pradesh and into northern regions like Punjab and Haryana, it began to face the issue of brackish water with high concentrations of dissolved solids. Because the UV process does not reduce the dissolved solids of brackish water, Naandi began looking for another solution. Naandi decided to partner with Tata Projects Limited in the use of a reverse osmosis plant. Reverse osmosis (RO), also known as hyper-filtration, is a purification process used in desalination plants to eliminate concentrated solutions like dissolved minerals and salts in water. Tata Projects installs and maintains the plants for the first year of operation. The plants use whatever water is available in the region, typically either pond water or bore-wells. The RO technology helps Naandi provide drinking water free of chemical contamination to villagers. In addition to providing a much cleaner bottled water-like taste, the RO system addresses arsenic, nitrate, sulfate, and other chemical contaminations.

In building the reverse osmosis system, three main parameters are used to determine the right system for a village, categorized as follows:

Village population <2,500 <5,000

<8,000

Plant flow requirement in liters per hour (a function of population as well as whether the village is located near highways, train stations, etc.) 250 500 1,000 1,500 2,000 3,000 5,000

Total dissolved solids in available village water (parts per million) <2k Low 2k-3k 3k-6k 6k-10k Brackish >10k Seawater Medium High

Based on information from the preliminary information report, Naandi sends the parameters to its partners, who design and deliver a plant best suited to the village.

Marketing

Naandi has recognized that instrumental to the success of the water program is behavioral change for the customers. For many, paying for water is a new idea, and the linkage between poor health and their current water source is not clear. Naandis Safe Water Program team is built around social marketers with experience ranging from rural sales of fast-moving consumer goods to well-recognized product brands to public health awareness about condoms. They have brought their experience in rural campaigns to develop the activities Naandi is using in Safe Water Program promotion. Pre-Launch Activities Marketing begins before the plant is inaugurated. Each village has a dedicated marketing program, designed based on the outcome of a community survey and a preliminary information report. With an understanding of the communitys demographics, entertainment profile, and additional data, the communications team spends one to two weeks planning its marketing approach.

8

DO

NO T

CO PY

<10,000 >10,000

Naandi does not deploy the same plant in every location; there are a number of village parameters that are considered, and each plant is customized to the individual village.

Bringing Safe Water to Indias Villages and Communities: The Naandi Foundation

1-428-987

All programs include school and community programs, film screenings, and a general information campaign. The school programs typically target elementary schools and are very interactive. For example, after a short lesson on illness and the difference between contaminated and clean water, children are asked to draw pictures representing the two different types. In other cases, children are directed through a play using masks showing the benefits of clean water. Naandi will also typically host two film screenings and provide the content to the local cable operator. The films, translated into the local language, discuss the benefits of clean water and speak more broadly about the Naandi Foundation. Included in the films is a feature newscast done by TV9 about Naandis Clean Water Initiative, which establishes credibility by a third party. Following the film session is a question and answer session hosted by the safe water promoter (SWP).

Naandi has also begun providing funds for wall paintings and other visual advertisements to raise awareness and act as a reminder and reinforcement media. Post-Launch Activities Post launch, the SWP becomes the primary figure in the marketing campaign. S/he will continue to interact with self-help groups, schools, and door to door contacts, working with families who are either not registered users, dropouts, or infrequent users. S/he performs demonstrations, answers questions (often covered on the Naandi FAQ worksheet). Using standardized surveys, ongoing assessments are conducted with customers to understand their needs, especially those that have chosen to not subscribe to date. Analytics and multivariable assessments of customers are used to refine and target campaigns to increase adoption rates. In addition, post-launch activities are being refined at a national level to become more interactive. The overall goal is to both increase the number of households using the safe drinking water and to encourage existing customers to use the water for more than just drinking. For example, demonstration manuals for cooking classes are under development that will showcase the benefits of using safe water in both cooking and washing of the food. One immediately demonstrable benefit is the reduced boiling time of water with fewer dissolved solids and higher digestibility of food.

Project Financing

Naandi has a diversified approach to locating start-up capital, working with a broad range of partners. In the Naandi model, nearly all capital and startup costs for the projects are raised before project initiation, with the operating revenue covering operational expenses. Startup funds come from four main sources: Naandi (typically around 2030% and funded internally or through debt), community contributions (typically a minimum of 10%), external donors, and technical partners (as in the case of WaterHealth India) and in some cases lenders. Individuals such as wealthy non-resident or resident Indians donate to support development in their native place or as part of their planned giving.

DO

NO T

9

CO PY

The structure itself is painted bright blue, which attracts new customers. In most units, the water purification unit is clearly visible, demonstrating to customers the high technology in place to create the product. In the village, this creates further excitement around the Naandi Safe Water Program and positions the product as aspirational even for those earning an average income of under $2 per day.

Bringing Safe Water to Indias Villages and Communities: The Naandi Foundation

1-428-987

Major external partnerships for start-up capital include:

20

FRANK Water UK-based charity FRANK Water supports clean water projects in the developing world. Founded by Katie Alcott after she had contracted dysentery by drinking dirty water in a visit to India, FRANK donates the profits from its affiliated bottled water business in the UK to support community access to safe water in rural areas. FRANK donates to specific sites based on village demographics, water quality, and health/ hygiene conditions. FRANK projects tend to target the most challenging areas. To date, FRANK funds have supported over 60 sites.

Debt Financiers Naandi is increasingly using debt financing to fund startup capital costs, paying back the debt over the five to six years that each project is Naandi operated. Revenue from operations would service and pay down the debt. Naandi has tentative agreements in place with an Indian Agricultural Bank and a foreign lender 23 that will fund multiple sites.

DO

Local Government Funds In addition to funds raised by the community, local governments in some cases contribute funds for the construction of the Naandi water plant. Local elected officials will allocate funds as part of the capital costs of the project, either directly from legislative assembly funds or through an affiliated NGO.

NO T

10

State Government Funds In Punjab and Haryana states, Naandi projects are largely financed with state funds. Expansion in those two northern states has been aggressive because of the strong public private partnership (PPP). Naandi replied to open tender offers published by the state governments requesting bids for safe water projects in various blocks throughout the states. To date, Naandi has won two out of three bids submitted. The government pays Naandi the majority of the startup cost 15 days after the site has been inaugurated. After five years, the plants become property of the state, rather than the Gram Panchayat as is the case elsewhere.

CO PY

Global Giving Through its website, individuals around the world donate to specific projects. Naandi water projects are posted on this website and aggregated funds have supported several projects, primarily in Punjab at this stage. The initial project aimed to provide safe drinking water to 25,000 Indians in ten sites in Andhra 21 Pradesh and close to $100,000 was raised for the projects. The World Bank Global Partnership and Output Based Aid (GPOBA) The World Banks GPOBA program has provided a grant of $850,000 to support 25 coastal sites in Andhra Pradesh, using exclusively UV technology. The program began in May 2007. Also in partnership in the program is WaterHealth International, the UV technology supplier and provider of a $200,000 supporting 22 loan, which will be repaid from user fees. The communities are also contributors to the project, providing 20% of the startup costs in each village. The World Bank disperses funds to Naandi upon completion of three milestones, linked to service delivery: plant inauguration, registration of a set number of below-poverty-line users, and continued use by a set number of users. In the interim, Naandi financed the projects through commercial borrowing, using the World Bank agreement as collateral.

Bringing Safe Water to Indias Villages and Communities: The Naandi Foundation

1-428-987

Pre-Launch Activities

A member of the project management team oversees the installation and inauguration of the plant. Despite rapid decline in costs over the last several years, the typical installation requires an average of 675,000 rupees (USD 13,500) in startup costs. The project manager oversees the following activities: Installation of the Reverse Osmosis or UV Unit Sourced from one of Naandis partners and acquired typically at below market rate pricing, these units range from 500 liters per hour capacity up to 5,000 liters per hour at the largest sites. Selection of the appropriate unit is based upon the results of an initial water sampling after site selection. Recently, Naandi has favored reverse osmosis technology as discussed above. Costs for units have fallen rapidly over the past several years, especially for RO units.

Installation of the Plumbing and Tanks Along with the purification unit itself, each water point requires two tanks, piping, and a disbursement area. Tanks range in size based on expected demand and can be upgraded or a tank can be added should it be required. Though early sites used stainless steel and other materials for tanks, current tanks are typically made of polyethylene, chosen because it is readily available, lightweight, strong, and hygienic. The tank for pre-filtered water is placed on the roof of the structure, while the clean water tank is housed inside the structure.

Pre-Launch Marketing

Described in detail above, social marketing about the benefits of clean water begins before the project is completed. Naandi budgets 50,000-100,000 rupees in initial project costs for marketing materials, depending on the project area. Operational Roles and Requirements After the launch of the product, retail sales managers oversee the function of all units, with reports coming from assistant managers, who are in turn informed by field coordinators. Operators and SWPs are reporting to the field coordinators and drawing upon them when maintenance or other needs arise. While Naandi continues to expand, overhead costs are not yet allocated to sites individually, as executive attention is focused on the rapid scaling.

11

DO

NO T

The design of the structures has evolved since Naandis first project in 2005. For example, initially the ceiling height was such that the storage tank could be cleaned only after removing it from the facility. With more ceiling height, this monthly cleaning could be done inside the structure, simplifying the process markedly.

CO PY

Construction of the Structure for Storefront and Unit Housing Naandi will place units in either pre-fabricated or complete locally built structures. Pre-fabricated structures require a locally built basement, which requires roughly 10 days to construct and costs between 48,000 and 55,000 rupees. The pre-fabricated structure is then delivered and erected in two days, at a cost of 150,000 to 170,000 rupees. In the case of a complete locally built structure, expected construction time is 45 days, with more variation during monsoon season. Costs are slightly lower, typically around 200,000 for the complete civil structure. Naandi accepts bids from local contractors to construct several units and selects its partner based on price and reputation.

Bringing Safe Water to Indias Villages and Communities: The Naandi Foundation

1-428-987

The Operator At each site, an operator runs the plant, conducts routine maintenance and tests, maintains the customer book, and oversees sales. He (the operator is typically male) opens the plant typically from 7 to 11 a.m. and from 4 to 7 p.m., seven days per week. He is responsible for ensuring that there is sufficient clean water available to customers and must adjust his schedule accordingly. In many villages, power can be intermittent or only during certain hours. The operator may have to run the plant during off hours to ensure a supply of water for the following day. Operators are also monitoring and logging the performance of the unit, logging daily outputs from the system and customer files. These are compiled into weekly reports given to their field coordinator. Safe Water Promoter (SWP) As discussed in the post-launch marketing section, the SWP has a set of duties to increase the number of registered families and the usage of those already registered. She will work closely with the operator as well to understand customers and their needs. SWPs are paid a salary equivalent to operators as well as incentives based on increases in the number of households over the initial baseline. Electricity Powering the unit requires a significant amount of electricity. The Gram Panchayat is required to provide the Naandi facility with an electricity connection but does not cover the cost of electricity. In India, electricity prices vary dramatically. In Andhra Pradesh, a typical 1,000 liter per hour (LPH) plant requires about 1,000 rupees per month of electricity. The same plant in Punjab, for example, costs nearly 2,0002,500 rupees per month in electricity.

Impact

Consistent with its professionalism, Naandi is not content with anecdotal evidence that clean water is eradicating poverty and improving lives. Naandi is conducting surveys before and after a plant is installed and in adjacent communities without plants to establish control groups for comparison. In the surveys, Naandi will establish baselines and track improvements in five categories: 1) health; 2) aspirations; 3) school attendance; 4) medical expenses; and 5) loss of wages. The surveys are being conducted by external partners to ensure independence and accuracy.

DO

In addition, the water from each unit is tested monthly at a lab in Hyderabad to assess the waters purity. Samples are sent through the field coordinators back to Hyderabad where a private lab conducts tests. Each test costs approximately 400 rupees (USD 8).

NO T

12

Routine Maintenance The operator is trained to perform routine maintenance on the filter. He will change filter cartridges when certain levels are noted on the instrument panel. The frequency of changes varies based on the condition of the incoming water. Each cartridge costs about 300 rupees and on average a cartridge lasts about two weeks. Non-routine maintenance is performed by dedicated professionals when needed, including the changing of membranes after three years for an RO system. Membrane replacements cost roughly 10,000 rupees each, with six required for a 1,000 LPH plant. Thus, after three years of operation, 60,000 rupees in membrane replacement charges is expected.

CO PY

Bringing Safe Water to Indias Villages and Communities: The Naandi Foundation

1-428-987

Discussion Questions

1. What is the Naandi value proposition and how does its value chain work through the pre-launch, operating, and ongoing maintenance phases of its activities? 2. What strategic resources and organizational competencies does Naandi need to execute its business plan? What knowledge, skills, and abilities does Naandi require to achieve its rapid growth plans? What additional partnerships should it consider? How should it structure and manage those partnerships? 3. What alternatives could Naandi pursue for its financial structure? Should it consider developing a franchise model like Piramal Water? Should it consider becoming a hybrid organization that combines a nonprofit structure for capitalizing new plant expansion with for-profit status for its operating units? Should Naandi consider taking on additional debt to support its plans for accelerating growth?

5. How would you adapt this model to fit local conditions in other countries? Urban or semi-urban areas?

DO

13

NO T

CO PY

4. Is the cost model sustainable when considering overhead and indirect expenses? What scale or adjustments are necessary for the model to be sustainable?

Bringing Safe Water to Indias Villages and Communities: The Naandi Foundation

1-428-987

Appendices

Appendix 1

Financial Analysis

The Naandi Safe Water Program has grown incredibly rapidly and has proven results in improving the lives of its customers. But are its financial structure and business model sustainable? Under what conditions is it truly possible to deliver safe drinking water to millions of people? Though Naandi is a nonprofit, this analysis evaluates its model as if were a for-profit entity, looking at revenue and cost structure and its scalability. Naandis Safe Water Program is almost entirely a fixed cost business. With the exception of some added costs of electricity for running a plant longer or potential additional membrane and cartridge replacements, all costs are fixed (salaries, plant deployment, corporate overhead, etc). It is therefore a volume business, not only for each plant in its water sales but also when overheada significant fixed costis considered. Therefore scale is essential on two levels. First, each plant must sell enough subscriptions to cover fixed costs, and the overall organization must have enough plants to sufficiently spread its overhead. The below analysis assesses Naandis revenue model and cost structure in more depth. The most straightforward way to analyze the business from a financial perspective is by examining the business at the plant level and then conducting an overhead cost analysis to charge each plant. As in any distributed business, there are variations and ranges of costs across regions and localities based on local conditions, and therefore this analysis is based on average figures. In future site selection, financial feasibility should be a first level consideration.

Plant Revenue

NO T

14

To date, Naandis revenue comes from one source: safe water subscriptions. As a result, Naandis revenue is a simple function of the price of water and quantity of sales. Naandis success to date has 25 been a direct result of its ability to achieve high customer penetration rates in each village. Naandi has done so with its sophisticated, highly specialized marketing campaigns. However, Naandi has not adjusted the other input of the equation, price. The elasticity of demand for the water is not known, though anecdotal evidence hints that non-subscribers are less concerned by the price than convenience of the plant. Assuming that anecdotal evidence is true, Naandi could increase price to raise revenue, making the model more financially viable. The below table shows the revenue effects of a rise in price and/or a rise in the number of customers. Raising prices could be viewed as antithetical to the overall mission of Naandi, eradicating poverty. Any price increase has an opportunity cost for the Naandi customers, who could have used those funds for another purpose. Or, if increased price means that certain customers can no longer afford Naandis safe water, then again financial targets are in conflict with the mission. Pricing the poor out of the market does not eradicate poverty.

Costs

Direct Costs The structure of direct costs is considered using the example plant in Exhibit 9. For this analysis, a single year is the unit of analysis because costs are constant for the life of the plant. For the membrane replacement, 26 equivalent annual cost is used with a 10% cost of capital and an assumed five-year lifespan.

DO

CO PY

24

Bringing Safe Water to Indias Villages and Communities: The Naandi Foundation

1-428-987

While salary and maintenance costs are generally consistent and stable, electricity costs can vary markedly by region. In Punjab, electricity rates and requirements can result in costs three times those listed. As explained below, this variation is not as financially material as changes in debt quantity or scale (for overhead reasons). Debt Financing The portion of the initial financing paid for using debt and the rate have material impact on the financial viability of a plant. For a 675,000 plant, 30% debt financing at 10% paid over the five years of operations costs over 50,000 rupees per year, more than the salary of one of the workers and equivalent to more than one-third of operating costs. Thus the startup costs and the structure of the payment are essential in determining viability. The chart below shows annual payment for debt based on size of the loan and interest rate, assuming a five-year repayment schedule. Percent equivalent debt financing is also shown for a 675,000 plant. The quantity of debt required to finance a project is the most important factor in determining financial viability. The interest rate is important, but pales in comparison to total debt burden. Naandi has typically used internal funds (or debt) to cover roughly 30% of up-front costs. Overhead The final major cost to consider is overhead. Because this analysis is at the plant level, an overhead equivalent should be determined based on a) a cost structure for corporate and managerial time, and b) the number of plants. In this analysis, every 12 plants are overseen by one field coordinator and 60 sites per regional manager. This analysis assumes a static corporate cost structure and a fixed cost for four state-level operations. Because of the requisite corporate and state level employee base, scale must be achieved to make the model viable. The below chart demonstrates the declining overhead charge based on an increased number of plants. (See Exhibit 11 for assumptions used and details.)

Summary The Naandi model is viable at scale and with limited debt burden. Direct operating costs account for a viable portion of revenues--roughly half. Increases in certain components of operating costs such as electricity or salaries unless sizable will not undercut the success of the model as written. However, quantity of debt (and interest rate) requires careful attention. A 675,000 plant financed with 30% debt, the typical Naandi contribution, requires annual payments just about 50,000 Rs, or one-fifth of revenue. Adding direct costs and debt burden, roughly 75,000 rupees are available to cover overhead costs (assuming

15

DO

NO T

CO PY

Bringing Safe Water to Indias Villages and Communities: The Naandi Foundation

1-428-987

the goal is break even). For burden rates to fall to that level, Naandi must achieve scale of over 1,000 plants, which it is slated to do in 2010. The model is viable but only if Naandi can continue its success in achieving scale both in penetration rates at the plant level and scaling out the number of plants to spread the overhead costs.

DO

16

NO T

CO PY

Bringing Safe Water to Indias Villages and Communities: The Naandi Foundation

1-428-987

Exhibits

Exhibit 1

India Country Profile

2000 Population, total (millions) Population growth (annual %) GNI, Atlas method (current US$) (billions) GNI per capita, Atlas method (current US$) GNI per capita, PPP (current international $) GDP (current US$) (billions) GDP growth (annual %) Inflation, GDP deflator (annual %) Agriculture, value added (% of GDP) Industry, value added (% of GDP) Services, etc., value added (% of GDP) Exports of goods and services (% of GDP) Imports of goods and services (% of GDP) Gross capital formation (% of GDP) Revenue, excluding grants (% of GDP) Cash surplus/deficit (% of GDP) Time required to start a business (days) Market capitalization of listed companies (% of GDP) Merchandise trade (% of GDP) 1,015.92 1.7 458.08 450 1,510 Economy 460.18 4.0 3.5 23 26 50 13 14 24 2005 1,094.58 1.4 805.64 740 2,210 808.71 9.2 4.1 19 29 52 20 23 35 2006 1,109.81 1.4 914.74 820 2,470 916.25 9.7 5.6 18 29 52 22 25 36 2007 1,123.32 1.2 1,069.43 950 2,740 1,170.97 9.0 4.3 18 29 53 21 24 38 .. .. 33 155.4 31

NO T

32.2 20

Source: World Bank World Development Indicators database, September 2008

Exhibit 2

Selected Water Standards

Allowable Particulates

DO

World Health Organization 1 45 50 1,500

Flouride (milligram/liter) Nitrates (milligram/liter)

CO PY

11.9 12.6 12.6 -3.9 -3.3 -2.7 .. 71 68.4 30 35 89.4 32 Bureau of Indian Standards (requirement) 1 45 300 500 Bureau of Indian Standards (permissible) 1.5 100 600 2,000 17

Naandi Water

1 45 300 500

Total Hardness (As CaCo3, milligram/liter) Total Dissolved Solids (miligram/liter)

Bringing Safe Water to Indias Villages and Communities: The Naandi Foundation

1-428-987

Exhibit 3

Diagram of Naandi RO Water Purification Technology

Tata Projects Limited Reverse Osmosis System RO technology uses a membrane that is semi-permeable, which allows only pure water to pass through it. During the process it rejects large contaminants passing through the membrane. Quality RO systems use a process known as crossflow, which allows the membrane to continually clean itself. RO requires a driving force to push the fluid through the membrane and, as some of the fluid passes through, the rest continues downstream, thereby sweeping the rejected contaminants away from the membrane. The unit, which is skid-mounted and designed for indoor installation, comprises a raw water pump that supplies water to the micron cartridge water filtration system and to the high pressure pump. Micron cartridge filters control the silt density before water enters into the membrane. The high pressure pump exists to boost water pressure as required.

DO

18

NO T

CO PY

Bringing Safe Water to Indias Villages and Communities: The Naandi Foundation

1-428-987

Exhibit 4

Naandis Safe Drinking Water Model

Community Level

Water source Land Support for education

Private Sector Partner

Technology Part financing Quality assurance

Naandi

Community mobilization Distribution Social marketing Mobilizing funds

Health communication

Source: Naandi Safe Drinking Water Business Plan. Available at http://www.nextbillion.net/lib/assets/documents/Naandi_Summary.pdf

DO

19

NO T

CO PY

Bringing Safe Water to Indias Villages and Communities: The Naandi Foundation

1-428-987

Exhibit 5

Naandi Safe Water Program Organization Structure

Behind the expansion of Naandi is an office team divided by region and function, supporting the growth of Naandi across India. There are national level managers in each of the function areas, and mirroring positions for each state. The state level managers report to both their state director and the national managers.

DO

20

NO T

CO PY

Bringing Safe Water to Indias Villages and Communities: The Naandi Foundation

1-428-987

State Directors Each state has a single director who reports to the national director. This individual manages the full team of state level managers. Retail Manager The primary point of contact for the assistant manager, the retail manager is responsible for the states units during their operation. Business Development Manager This individual is in charge of securing capital for the expansion of the number of sites. S/he works to find and secure funding from all available sources. Project Implementation Manager With a site selected and funds committed, the project implementation manager oversees the entire setup of a plant from soup to nuts. At the inauguration of the plant, the role of the project implementation manager is complete for that plant. Marketing Manager This individual oversees all communications, campaign, and public relations required to increase customers at the plant. S/he will target communications to each site while also working with the national marketing manager to develop new materials. Maintenance Part of the technical team, the maintenance manager ensures the consistent operation of all plants across his/her state. To date, much of the maintenance has been performed by Naandis technical partners (i.e. Tata Projects Limited, WaterHealth International, Malthe Winje), partially because the first year of maintenance is typically included in the price of the RO or UV unit. However, going forward, maintenance on units will become a challenge for Naandi. Consideration of the launch of a separate water system service entity, possibly for profit, which could service both Naandis and other companies units, is under way. Assistant Manager The intermediary between headquarters and the field coordinators, the assistant manager works with field coordinators overseeing collections, maintenance calls, and support to plants as needed. Each assistant manager is responsible for several districts and multiple field coordinators.

DO

Field Coordinator (FC) For each 12 plants (on average), a field coordinator is appointed to oversee the activities at the sites. The field coordinator serves as an intermediary with reports directly to an assistant manager, who liaises with state level. The FC is expected to visit two villages per day, checking in and collecting the weeks subscription payments. These payments are deposited daily at the local bank. FCs are hired locally, staying typically in the larger town in the region. In some cases FCs also serve as translators between village-level dialects and Naandi headquarters.

NO T

21

CO PY

Bringing Safe Water to Indias Villages and Communities: The Naandi Foundation

1-428-987

Exhibit 6

Naandi Safe Water Program Growth

Exhibit 7

Naandi Safe Water Program Pro Forma Income Statement

Projected Income Statement (thousands USD) 2008 # of plants Population of villages served Revenue from sales Total expenses Net income Capex required Naandi contribution Ending cash 300 1,500,000 1,782 2009 2010 1,000 2,200

CO PY

2011 2012 ,4300 4,300 9,000,000 15,765 8,492 7,273 15,000,000 37,469 17,411 20,058 52,408 31,445 (10,054) 6,522 37,469 20,893 16,576 27,225 16,335 (9,149)

2013 4,300 37,469 25,071 12,398

NO T

6,358 2,161 4,871 (379) 1,487 5,625 14,438 4,219 9,096 (1,677) (5,532)

4,000,000

18,920

Notes Capex per village estimated to increase because of materials costs and other factors Naandi contribution includes debt financing

DO

Naandi Foundation Community Contribution Private Donor (NRI)

Exhibit 8

Naandi Example Plant Sources and Uses

Example 1000 Liter Per Hour Naandi Plant, Startup Sources and Uses (Rupees) Sources 202,500 Plant & Machinery 100,000 Civil Structure 372,500 Storage Tanks & Piping Project Coordination & Community Mobilization Uses 375,000 175,000 75,000 50,000 675,000

Total

675,000 22

Bringing Safe Water to Indias Villages and Communities: The Naandi Foundation

1-428-987

Exhibit 9

Naandi Example Plant Pro Forma Income Statement

Assumptions Startup Costs (Rs) Sales (l/d) Price (Rs/l) SWP Salary (Rs/year) Operator Salary (Rs/year) Electricity Cost (Rs/year) Cartridges (Rs/year) Membrane Replacement (Rs) Information Education Communication Program Miscellaneous % Financed by Naandi Debt Total Debt Interest Rate Term (years) Year Revenue Liters Sold Rs/l Total Revenue SWP Salary 0.1 1 Field Coordinator Apportionment (Rs/year) 675,000 6,500 0.1 36,000 36,000 12,000 12,000 75,000 36,000 6,000 12,000

2,372,500 2,372,500 237,250

NO T

237,250 36,000 36,000 36,000 36,000 12,000 12,000 12,000 12,000 36,000 36,000 6,000 12,000 6,000 12,000 (150,000) (150,000) 87,250 (53,419) 33,831 87,250 (53,419) 33,831 23

Direct Operating Costs Operator Salary Electricity Cost Cartridges

Membrane Replacement IEC Program

DO

Miscellaneous

Field Coordinator Appointment

Total Operating Costs Annual Gross Profit Debt Payment Due Net

CO PY

30% 10 5 202,500 2 3 4 5 2,372,500 2,375,500 0.1 237,500 36,000 36,000 12,000 12,000 75,000 36,000 6,000 12,000 36,000 6,000 12,000 36,000 6,000 12,000 (150,000) 87,250 (53,419) 33,831 2,372,500 0.1 0.1 237,500 36,000 36,000 12,000 12,000 0.1 237,500 36,000 36,000 12,000 12,000 (150,000) (150,000) 12,250 (53,419) (41,169) 87,250 (53,419) 33,831

Bringing Safe Water to Indias Villages and Communities: The Naandi Foundation

1-428-987

Exhibit 10

Naandi Overhead Calculation Per Plant

Annual Overhead Charge Per plant (Lakh Rupees) Number of Plants 200 400 600 800 1000 1500 2000 2500 3000 3500 4000 4500 Number of Assistant Managers 4 7 10 14 17 25 34 42 50 59 67 75 Number of Field Coordinators 17 34 50 67 84 125 167 209 250 292 334 375 Overhead Impact/ Plant 3.575 1.903 1.342 1.069 0.901 0.677 0.568 0.500 0.455 0.424 0.400 0.381

DO

24

NO T

CO PY

Bringing Safe Water to Indias Villages and Communities: The Naandi Foundation

1-428-987

Exhibit 11

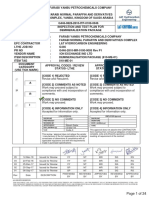

Selected Naandi Documents 11.1: Primary Information Report

DO

25

NO T

CO PY

Bringing Safe Water to Indias Villages and Communities: The Naandi Foundation

1-428-987

DO

26

NO T

CO PY

Bringing Safe Water to Indias Villages and Communities: The Naandi Foundation

1-428-987

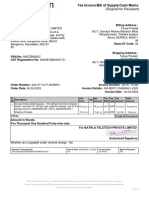

11.2: Frequently Asked Questions Used by Safe Water Promoters (selected)

DO

NO T

CO PY

27

Bringing Safe Water to Indias Villages and Communities: The Naandi Foundation

1-428-987

DO

NO T

28

CO PY

Bringing Safe Water to Indias Villages and Communities: The Naandi Foundation

1-428-987

Exhibit 12

Piramal Water Profile28

Piramal Water Private Limited is another community-scale water provider in India and is running a model similar to Naandis. The company was established in mid-2008, with a for-profit aim to find viable mass-market solutions to Indias drinking water crisis. Piramal Water operates under the brand Sarvajal. The enterprise has its roots in the work of the Piramal Foundation, a charitable trust established by Ajay G. Piramal. The foundation initially piloted the Bagar Drinking Water Initiative as part of the nonprofit group Indicorps Grassroots Development Laboratory in the Shekhawati region of Rajasthan, where fluoride contamination in drinking water has led to many premature health problems. The successful pilot in Bagar proved to the Piramal family that development interventions could work via a sustainable business model.

Piramal Water owns, installs, services, and maintains the water purification plants that are customized by location and source water quality. They currently employ reverse osmosis systems that have been sourced from a global supply chain. Franchisees are water entrepreneurs who are trained to operate the units, ensure the highest standards of hygiene, and promote the benefits of pure drinking water to their communities. As a part of their franchise fee, they are provided with a business startup kit that includes health promotion materials, operations manuals, marketing collateral, branding tools, and business development resources. In addition, a Sarvajal representative is available to assist new franchisees on-call and on-site during the first few months of operation to ensure that each outlet generates a reliable customer base by promoting the benefits of clean drinking water. Like Naandi, Sarvajal is testing out new technologies to improve the experience for the consumer as well as helping to make the low-cost, distributed business model viable for its deployment conditions. This includes developing cutting-edge technological solutions that help keep track of Sarvajal machinery, the performance of each franchisee, and the way end customers use the products and services.

DO

29

NO T

CO PY

Piramal Waters operations rely on a franchise model (there are both entrepreneur-owned and companyowned outlets) that enables rural entrepreneurs to start businesses that provide purified drinking water to their communities. Customers purchase prepaid cards in 10L and 20L denominations; they come to the outlet to purchase water either in their own containers or in jerry cans purchased from Sarvajal. Some franchise locations also offer economical daily delivery of water.

Bringing Safe Water to Indias Villages and Communities: The Naandi Foundation

1-428-987

Exhibit 13

Water Treatment Plant Projects with Private Participation in Developing Countries by Region, 19902008

Source: World Bank and PPIAF, PPI Project Database

Exhibit 14

Private Investment in Developing Countries by Sector

DO

Source: World Bank and PPIAF, PPI Project Database

NO T

30

CO PY

Bringing Safe Water to Indias Villages and Communities: The Naandi Foundation

1-428-987

Exhibit 15

Treatment of Contaminated Waters for Human Consumption Overview of Alternatives

Source: Hammond, Al, Jim Koch, and Francisco Noguera. Safe Water Drinking for All. The Global Social Benefit Incubator. Santa Clara University and New Ventures, World Resources Institute. November 2008. p. 5. <http://www.nextbillion.net/lib/assets/documents/Safe_Drinking_Water_for_All.pdf>.

DO

31

NO T

CO PY

Bringing Safe Water to Indias Villages and Communities: The Naandi Foundation

1-428-987

Endnotes

1

Excerpted from a speech of Dr Manmohan Singh at the Conference of Ministers in Charge of Rural Drinking Water Supply and Sanitation. January 2006. <http://pmindia.nic.in/speech/content.asp?id=271>. Hull, Jeff. Water, Water, Everywhere. Fast Company. <http://www.fastcompany.com/magazine/132/water-water-everywhere.html>. <http://www.unesco.org/water/wwap/facts_figures/mdgs.shtml>. Prss-stn, A., R. Bos, F. Gore, and J. Bartram. Safer water, better health: costs, benefits and sustainability of interventions to protect and promote health. World Health Organization. Geneva: 2008. Briscoe, John. India's Water Economy: Bracing for a Turbulent Future. The World Bank. 2006. <http://go.worldbank.org/ QPUTPV5530>. Ferguson, Kevin. Indias Water Woes, Continued. The New York Times. 17 July 2009. <http://greeninc.blogs.nytimes. com/2009/06/17/indias-water-woes-continued/>. Building From the Past. National Driller. 1 Dec. 2000. <http://www.nationaldriller.com/Articles/Cover_Story/ c9275bc6c6197010VgnVCM100000f932a8c0>. Ibid. <http://www.juerg-buergi.ch/Archiv/.../McNamara_Nairobi_speech.pdf>.

2 3 4

8 9 10 11

Mehovich, Jasmin, and Janaki Blum. "Arsenic Poisoning in Bangladesh." South Asia Research Institute for Policy and Development. 8 Sept. 2004. <http://www.sarid.net/sarid-archives/04/040908-arsenic-poisoning.htm>. <http://www.worldwatercouncil.org/index.php?id=708&L=0%2C24%25%252>. <http://www.unicef.org/sowc96/1980s.htm>.

12 13 14 15

Gilbert, Steven G. "A Small Dose of Toxicology: The Health Effects of Common Chemicals." CRC Press. New York: 2004. Additional information on LifeStraw is available at <http://www.vestergaard-frandsen.com/lifestraw.htm>. PUR, a division of Procter & Gamble, has developed a sachet of chemicals for purification for individual and small-scale use. Additional information is available at <http://www.cdc.gov/safewater/publications_pages/pubs_pur.htm and http://www.pghsi.com/pghsi/safewater/>. 20 liters was chosen because it allows an average family of five to have four liters of water each per day. Because of the varying needs of families, Naandi is currently experimenting with 5- and 15-liter subscription plans in some districts.

16 17 18

19

Academic research has shown that education and awareness have nearly equal effect as price in purchasing decisions of drinking water. See for example Jalan, Jyotsna, et al. Awareness and Demand for Environmental Quality: Drinking Water in Urban India. Indian Statistical Insitute. September 2003. <http://www.isid.ac.in/~planning/workingpapers/dp03-05.pdf>. This is not an exhaustive list. There are several other partners not mentioned, including The Eleos Foundation, Global Water Challenge, The Coca-Cola Foundation, AAPICF & APMGUSA, various state governments, members of Parliament and legislative assemblies, as well as Rotary Club International. <http://www.globalgiving.com/projects/village-india-water-supply/>. <http://www.gpoba.org/activities/details.asp?id=46>. See also the GBOPA Note, Output-Based Aid in India: Community Water Project in Andhra Pradesh, available at <http://www.gpoba.org/docs/OBApproaches21_IndiaWater.pdf>. Early projects partnered with WHI did use a form of debt. At that time, WHI would borrow money from a local bank to pay for the startup cost of the project. WHI controlled collections at the site after plant inauguration and used collected funds to pay back the initial loan. Naandis role was largely social marketing toward the use of safe water in the villages. In certain cases, the Acumen Fund would guarantee a portion of the loan. For further detail, see the Institute for Financial Management and Research case study Community-owned Safe Water ProjectNaandi, WHI and ICICI, available at <http://www.ifmr.ac.in/pdf/casestudy/1/ Naandi_CSNov06.pdf>. Naandi also sells jerry cans but essentially at cost. For the purpose of this analysis, that revenue is ignored. In the future, Naandi may be able to increase revenue and profits by increasing the number of products and services on offer by either selling through the storefront directly or through partnerships with other vendors. Rate of adoption in the village is an additional factor to consider, though not included in this analysis. Naandi has achieved high penetration in villages fairly quickly, limiting the potential impact on revenue of adoption times. However, in other circumstances, this could significantly impact the cash flow of the plant. Equivalent annual cost is used because when scaling this analysis to the multiple plants, replacements should spread more evenly across years. The membrane life is also closer to three years on average. However, the initial unit includes a membrane and because the plant is handed off after five years, only one replacement is needed. <http://www.naandi.org/provide_drinking_water/ReverseOsmosis.aspx>. <http://www.sarvajal.com/> and company executive interviews.

20

21 22

23

24

25

26

27 28

DO

NO T

32

This will of course vary by village because of input costs and number of customers. See Exhibit 9 for a model pro forma income statement of a plant.

CO PY

Chlorine Disinfectants Critical to Combating Global Infectious Diseases. American Chemistry Council. 2 May 2005.

Bringing Safe Water to Indias Villages and Communities: The Naandi Foundation

1-428-987

Notes

DO

33

NO T

CO PY

Bringing Safe Water to Indias Villages and Communities: The Naandi Foundation

1-428-987

Notes

DO

34

NO T

CO PY

Bringing Safe Water to Indias Villages and Communities: The Naandi Foundation

1-428-987

Notes

DO

35

NO T

CO PY

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- AJMRSP1009Dokumen16 halamanAJMRSP1009manujsriBelum ada peringkat

- Tcs Bancs On SbiDokumen9 halamanTcs Bancs On SbiSushil GoyalBelum ada peringkat

- AJMRSP1009Dokumen16 halamanAJMRSP1009manujsriBelum ada peringkat

- AJMRSP1009Dokumen16 halamanAJMRSP1009manujsriBelum ada peringkat

- Creating A New Industry: Click To Edit Master Subtitle StyleDokumen4 halamanCreating A New Industry: Click To Edit Master Subtitle StyleDaksh SethiBelum ada peringkat

- SBI TransformationDokumen8 halamanSBI TransformationReaderrBelum ada peringkat

- Dell Case 2Dokumen10 halamanDell Case 2Daksh SethiBelum ada peringkat

- SBI TransformationDokumen8 halamanSBI TransformationReaderrBelum ada peringkat

- CH 12Dokumen20 halamanCH 12Daksh SethiBelum ada peringkat

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (344)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (73)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2259)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (120)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)

- The Entrepreneurial ProcessDokumen13 halamanThe Entrepreneurial ProcessNgoni Mukuku100% (1)

- Pages From g446 0828 2810 Itp 0100 0046 Rev 05 Final Approved 2Dokumen4 halamanPages From g446 0828 2810 Itp 0100 0046 Rev 05 Final Approved 2Vinay YadavBelum ada peringkat

- ICI Vol 43 29-11-16Dokumen32 halamanICI Vol 43 29-11-16PIG MITCONBelum ada peringkat

- Shivani Singhal: Email: PH: 9718369255Dokumen4 halamanShivani Singhal: Email: PH: 9718369255ravigompaBelum ada peringkat

- Medical Devices and Ehealth SolutionsDokumen76 halamanMedical Devices and Ehealth SolutionsEliana Caceres TorricoBelum ada peringkat

- Eco-Bend: CNC Hydraulic Press BrakeDokumen9 halamanEco-Bend: CNC Hydraulic Press Brakehussein hajBelum ada peringkat

- (70448314976) 08112022Dokumen2 halaman(70448314976) 08112022DICH THUAT LONDON 0979521738Belum ada peringkat

- Recruitment, Selection, Induction, Training and Development ProcessDokumen4 halamanRecruitment, Selection, Induction, Training and Development ProcessMayurRawoolBelum ada peringkat

- Strategy Implementation - ClassDokumen56 halamanStrategy Implementation - ClassM ManjunathBelum ada peringkat

- TCI Letter To Safran Chairman 2017-02-14Dokumen4 halamanTCI Letter To Safran Chairman 2017-02-14marketfolly.comBelum ada peringkat

- CR 2015Dokumen13 halamanCR 2015Agr AcabdiaBelum ada peringkat

- Share Holders Right To Participate in The Management of The CompanyDokumen3 halamanShare Holders Right To Participate in The Management of The CompanyVishnu PathakBelum ada peringkat

- McMurray Métis 2015 - Financial Statements - Year Ended March 31, 2015Dokumen13 halamanMcMurray Métis 2015 - Financial Statements - Year Ended March 31, 2015McMurray Métis (MNA Local 1935)Belum ada peringkat

- Corporation Law DigestsDokumen18 halamanCorporation Law DigestsDonnBelum ada peringkat

- Sr. No. Name of Institution Address Board Line Fax No.: 1 Allahaba D BankDokumen9 halamanSr. No. Name of Institution Address Board Line Fax No.: 1 Allahaba D Banksaurs2Belum ada peringkat

- Competitors and CustomersDokumen2 halamanCompetitors and Customerslk de leonBelum ada peringkat

- River Eye Fashion CompanyDokumen11 halamanRiver Eye Fashion Companyriver eyeBelum ada peringkat