Eco-Before The Model

Diunggah oleh

Pramesh ChandDeskripsi Asli:

Judul Asli

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Eco-Before The Model

Diunggah oleh

Pramesh ChandHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Oil Price Fluctuations: Related Policies and their Impact on India

Submitted To : Prof. Chandan Sharma

PGP28237 - Aishwarya Kirthivasan PGP28239 - Bharti Yadav PGP28240 - Muhammed Rijas PGP28249 - Sruti Pujari PGP28250 - Anju R. Gothwal PGP28271 - Nisha Bachani PGP27276 - Pramesh Chand GROUP-8 |Section E |IIM Lucknow, 2012-14

I.

Abstract

This project report analyses the effect of transmission of international oil prices and domestic oil price pass-through policy on major Indian macroeconomic variables. The three prime channels of transmission viz. import channel, price channel, and fiscal channel are explored with the help of a structural macroeconomic framework. A macroeconomic policy simulation model is used for the analysis. The policy of deregulation of domestic oil prices in the premise of occurrence of a one-time shock in international oil prices as well as no oil price shock situation is analyzed through its impact on growth, inflation, fiscal balances and external balances during the 12th Plan period of 2012-13 to 2016-17. The simulation results reveal that in the short run the deregulation policy would have adverse impact on the growth and inflation. But if complemented with the policy of switching of subsidy bill to capital expenditure it might result in positive growth effects in the medium and long run. Given, the current pass-through policy, one-time oil shock has adverse impact on growth and inflation in the year of shock while it mitigates slowly over time. The model shows that with the oil shock and with current partial pass-through regime, a 10 percent rise in oil prices result in a 0.6 percent fall in growth while in the full pass-through situation, it can reduce the growth by 0.9 percent. The pass-through policy has differential impact on growth and inflation over the 12th Plan period. Hence, the policy of oil price deregulation must be carefully weighed and prioritized.

II.

Rationale Behind The Analysis

International oil prices have seen frequent sharp increases since 2002, spiking to more than $140 per barrel in mid-2008. UNCTAD (2008) calculations showed that in developed countries the fuel import bill increased from 1.6 percent of their GDP in 2002 to 3.6 percent in 2007. In developing countries, the fuel import bill rose from 2.7 percent of GDP in 2002 to about 5 percent in 2007. These ratios were estimated to amount to about 6 percent of GDP and 8 percent respectively at an average oil price of $ 125 per barrel in 2008 in the same study. In India, similarly, the net oil import to GDP ratio has gone up from less than 3 percent in 2003-04 to more than 5 percent during 2008-09. Though oil prices fell in the interim, current trends again show significant increases, with analysts predicting high oil prices in the foreseeable future (IMF 2011). Combined with the world-wide slowdown in economic activity and political instability in the MENA countries, the implications of a further rise in international oil prices could be alarming for oil importing economies. While the oil importing countries, even large ones like India are price-takers in the international oil market, countries usually exercise discretion in passing on international price shocks to domestic prices. In India the administered price system has traditionally offered a mechanism to cushion the international price changes and achieve domestic policy objectives on inflation, growth and equity. The administered price system for oil is supported by budgetary expenditures (subsidies), even as revenues from oil constitute a significant portion of the overall revenues for the government. The pass-through policy, presently on the reform agenda, thus has important implications for the way international oil price changes impact the macroeconomy.

As the entire country, particularly the poor people, are reeling under heavy pressure of inflation, the UPA government has hiked the prices of diesel, kerosene and LPG by Rs 3 per litre, Rs 2 per litre and Rs 50 per cylinder respectively. The reasons given for this move can be broadly categorized as follows: 1. The prices have merely moved in tandem with the international prices. 2. The government could not take the burden for it more than what it already takes in the form of heavy subsidies for various petroleum products. 3. There is a case for deregulation of prices of these three products on the lines of petrol as it is becoming unsustainable for the exchequer and the public sector oil companies who are facing 'under-recoveries' for a long time. This step is a forward movement in that direction. 4. In a period of inflation, such increase in prices would bring the demand down and, hence, would put a downward pressure on inflation. This note attempts to analyze these arguments by presenting both the factual picture and the economic logic behind these arguments. In this regard, there are four major findings. Firstly, it is found that despite deregulation of petrol, the prices in India are significantly higher than the world prices. Secondly, a large portion of the retail prices that the consumers end up paying consists of taxes levied by both the central and state governments. Thirdly, the government is heavily subsidizing the petroleum products and hence deregulation is the only way forward. In fact, we find that government's receipts through taxes are markedly higher than the subsidies that they provide on petro-products. Lastly, we address the last point mentioned above that this step would help ease inflation.

III.

Introduction

International Crude Oil prices have risen steadily over the past two years. If one were to visualize the web of interactions among the relevant variables one would have to consider the Dollar Value and Volumes of Crude Oil imports, Forex rates, Household consumption, Private Investments, Government Investments and Consumption, Net Exports (Exports minus Imports), Inflation, Interest rates besides other factors like business sentiments, fiscal deficit, etc. Aggregate Demand is composed of four components, namely Household Consumption (C), Government Consumption & Investments (G), Private Investments (I) and Net Exports (X).

(a)

Impact on Net Exports (X)

The first direct impact of Crude Oil price rise has been to increase the cost of imports. As Crude Oil forms a large part of the Indian import basket (approx. 30-32%), any price rise in crude has a sizeable impact on the cost of imports. In the past 2 years, the quantity of Crude Oil imports has more or less remained constant (refer Graph 4) but it is important to note that imports account for around 80% of Indias Crude Oil requirement, the remaining being sourced from domestic crude oil sources. Crude Oil demand has remained inelastic in the past two years as tendency has been to maintain the growth momentum causing the cost of Crude Oil imports to increase. As Crude Oil procurement in international markets is Dollar driven, this has led to a higher Dollar demand leading to depreciation of the Indian Rupee. It is important to note that although Crude Oil has been a major contributor to depreciation, other factors like Gold imports and reduced FII inflows (as a result of persistently high fiscal deficit leading to reduced Dollar supply) have also played a part in the downslide of the rupee. The downward pressure on the rupee would ideally make exports more competitive at the expense of imports but in light of the of recession-like conditions prevailing in EU and US, the export demand itself has taken a hit leading to

overall decrease in value of exports. Thus, the net impact of exchange rate has been to increase the cost of imports although the quantity imported has not increased. In fact, recent imports trend shows that from July `11 onwards the overall Indian imports have (on average) remained stagnant at around $38- $40 billion, barring some volatility, while the Rupee has depreciated by approximately 27% (~Rs 44/$ to Rs 56/$) (refer Graphs 1 & 2). Therefore, in Rupee terms, imports have increased reducing the Net Exports (X) component of aggregate demand.

(b)

Impact on Household Consumption (C)

The second impact of the Crude Oil price rise has been to increase the cost of production. Considering that Crude Oil fractions have wide-ranging applications, like in diesel for trucks and railway locomotives, fertilizers and pesticides for agriculture, plastic-manufacturing, it would not be difficult to understand the reason for increased cost of production of a wide ranging set of goods and services dependent on various

crude oil fractions. This increase has been a major contributor to Cost -Push Inflation as, in such cases; producers tend to protect their margins by offsetting the increase in cost of production by increasing the prices. High inflation coupled with the negative sentiments attached to uncertainty of future prices have led to reduction in Household Consumption (C). It is important to note here that the complete price rise is not transferred to the consumer.

(c)

Impact on Government Consumption (G)

The Government cushions the impact through various fuel subsidies, also called the Administe red Pricing Mechanism, which increases the Governments Revenue Expenditure. However, contrary to popular notion, there is practically no subsidy burden of Crude Oil on the Government as the Revenue Receipts from Crude Oil, in the form of Sales Tax, VAT, Excise and Customs duty, more than offset the subsidy. Although partial pass-through of price rise cushions the fall in household disposable income, which has a positive impact on Aggregate Demand, this approach may not be sustainable in the long run considering the supply side bottlenecks and the fiscal deficit. It would, therefore, be advisable for the Government to reallocate the money used for subsidy to more productive channels, like incentivizing the search for Crude Oil sources domestically or long-term capital formation through infrastructure development. Moreover, the government should decrease its dependency on Crude Oil, especially Petrol, as a revenue-generating mechanism considering the fact that a sizable portion of the cost to consumer is due to the plethora of taxes. A case in point is the cut in VAT on Petrol by the Goa state government (effective 2nd April`12) from 20% to 0.1% bringing the prices down from approximately Rs 65 to Rs 55. Obviously, such actions would reduce revenues for the state but an effort needs to be made to find viable alternatives for income generation. For example, the Government could look at increasing its stake in profit-generating PSUs instead of disinvesting, along with working towards increasing realizations from other existing taxes.

(d)

Impact on Private Investment (I)

Finally, private investment has reduced due to negative business expectations from the future due to decreasing Aggregate Demand and persistently high interest rates.

Overall Impact and RBIs Monetary Policy stance

The overall impact of the Crude oil price rise, therefore, has been to reduce the GDP growth rate which would lead to higher involuntary unemployment levels. The accompanying Cost-Push Inflation has hit the people at the bottom-of-the-pyramid the hardest. This peculiar situation, where the GDP growth is decreasing but inflation is high, is called stagflation. RBIs traditional stance has been to give priority to curbing inflation in the trade -off between inflation and growth, causing it to pursue a tight monetary policy. To curb the high inflation rates in FY`10-11, RBI increased policy rate by 525 basis points (bps) from 3.25% in March `10 to 8.5% in March`11. More than 13 hikes in the Repo Rate along with increase in CRR in the past two years has led to reduced lending and therefore, reduced investments. RBIs thought -process seems to be that by sucking liquidity from the system, Aggregate Demand will decrease sufficiently to curb inflation. However, in the current scenario where inflation faced is Cost-Push and not Demand-Pull, the rationale behind continued rate hikes is not apparent. In Indias case, the major contributors to inflation are Crude Oil and Food inflation, so unless the supply side constraints are addressed, monetary policys impact on inflation will be minimal. RBI has justified its actions by citing both supply and demand-side pressures (following postrecession recovery), their rationale being that many manufactures have taken the alibi of increased production costs by passing on the complete increase to the consumer instead of decreasing the mark-up. By assuming a tight monetary policy, RBI aims to send a consistent signal into the market that it will not buckle under pressure and that inflation being the priority, RBI will not shy away from increasing rates to curb demand. This would force manufacturers to reduce their mark-up to drive sales, thereby decreasing prices to a certain degree.

IV.

Review of Literature

(A) Oil shock and its transmission through the supply side

A key insight from prior studies on oil and the macroeconomy is that the magnitude of the effect of oil price shock on gross output must be small. Assuming an aggregate production function with three inputs (labour, capital, and oil) at full employment equilibrium, marginal productivity of oil equals the ratio of oil to output prices, i.e., the marginal cost of oil measured in terms of domestic product. An increase in price of oil raises its cost above marginal product leading to a cutback in amount of oil used in the production. In the process, marginal productivity of labour and capital declines and there is a fall in output. Lower the elasticity of substitution between oil and other inputs, larger will be the fall in GDP. These models predict only small changes in output when applied to real data, and are unable to explain why oil price shock should trigger downturns as sharp as those of the 1970s. A one percent reduction in oil usage reduces gross output by a percentage corresponding to the cost share of oil. 2 This share of oil in output is thought to be no larger than 4 percent and may be much smaller. Thus, a 10 percent increase in oil prices, for example, should result in a less than 0.5 percent reduction in gross output (Rotemberg and Woodford, 1996). However, following the Suez crisis in 1956, the drop in US real GDP was 2.5 percent, and the 1973 oil shock produced a 3.2 percent drop in US real GDP (Hamilton, 2003). To explain the much higher real drop in GDP, researchers have turned to additional transmission mechanisms by which oil price shocks might contribute to lower growth, e.g., capital equipment utilisation; uncertainty and investment pauses; labour markets; sectoral shocks. Besides extending the number of channels through which the oil shocks play out, many of the models have invoked the theory of imperfect competition to explain the facts. The intuitive idea behind most of these models, as discussed below, is that an increase in the price of energy works like a negative technology shock to generate contraction in economic activity. Finn (2000) develops a model with perfectly competitive markets, but incorporates energy as an essential input for the utilisation of capital. This creates an indirect channel, working through the capital stock, in addition to the usual direct production function channel, for transmitting the impact of fluctuations in energy usage to the macroeconomy. Oil price increases depress the future marginal product of capital, thereby reducing investment and the future capital stock, and thus can have long-term effects on output. Using this model, Finn was able to arrive at much larger quantitative effects than the traditional studies in this area. A different class of explanations emphasises the frictions in reallocating labour or capital across different sectors that may be differentially affected by an oil shock. For example, one common consequence of an oil price shock is a sudden drop in demand for certain kinds of cars, which leads to lower capacity utilisation at affected plants (Bresnahan and Ramey, 1993). Because labour and capital can move to alternative productive activities only at a cost, the result is idle resources that can significantly multiply the effects described above.

Some of the channels described above have not been subjected to rigorous empirical testing, so caution is required in generalising from these results. Also, the very different response of real output and prices in recent episodes of oil price increases (IMF, 2007; Blanchard and Gali, 2009) requires fresh research on the theoretical and empirical relationship between oil price shocks and gross output. (B) Oil shock in a demand constrained economy

The following survey explores the impact of an oil-price rise for an economy with less than fullemployment output, and with high levels of involuntary unemployment. Trade channel Given the preponderance of oil imports in the import basket of the developing countries and their growing energy needs, an increase in oil price would lead to a worsening of trade balance, given a fixed exchange rate. The decline in trade balance works through movements in terms of trade. Rakshit (2005) points out that for examining the effect of an oil shock in terms of an open economy macro model we need to distinguish between two price ratios or terms of trade: (a) ratio of oil price to the domestic price level; and (b) the ratio of the price level of non-oil importables to that of domestic goods. The countrys trade balance is negatively related to (a), but im proves with an increase in (b). Since the proportional rise in the domestic price level is less than that in crude oil prices, an oil shock raises (a), but lowers (b). Thus, the result relating to worsening of the trade balance and the consequent fall in aggregate demand and GDP through the foreign trade multiplier is clear cut. The assumption here is that the nominal exchange rate is fixed, so that a rise in domestic prices, ceteris paribus, results in real exchange rate appreciation. However, if the nominal exchange rate is flexible, oil importing countrys currencies will depreciate, while oil exporters currencies will appreciate in response to their real income gains. Over time, the initial oil trade deficit will decrease, and the non-oil trade balance will increase. Thus the fall in real output, or at least a part of it, might be temporary in the oil-importing economy. The theoretical case for flexible exchange rates rests on the ability of flexible exchange rates to absorb adverse oil shocks that obviates the need for a prolonged adjustment through excess demand in the goods and labour markets to push prices and wages to the new equilibrium. This hypothesis was tested and affirmed by Al-Abri (2007) for nine major OECD countries between 1973 and 2004. Consumption and investment channel In a recent survey on the effects of energy price shocks, Hamilton (2008) stresses that a key mechanism through which energy price shocks affect the economy is the disruption in consumers and firms spending on goods and services other than energy. This view is consistent with evidence from industry as most U.S. firms perceive energy price shocks as shocks to the demand for their products rather than shocks to the cost of producing these products.

There are four complementary mechanisms by which energy price changes may directly affect consumer expenditures (see, Edelstein and Kilian, 2009). 1. First, higher energy prices reduce discretionary income, as consumers have less money to spend after paying their energy bills. Other things being equal, this discretionary income effect will be larger the less elastic the demand for energy. But even with perfectly inelastic energy demand, the magnitude of the effect of a unit change in energy prices is bounded by the energy share in consumption. 2. Second, changing energy prices may create uncertainty about the future path of the price of energy, causing consumers to postpone purchases of consumer durables (see, Bernanke, 1983). Unlike the first effect, which applies to all forms of consumption, this uncertainty effect is limited to consumer durables. 3. Third, consumption may fall in response to energy price shocks, as consumers increase their precautionary savings. 4. Finally, consumption of durables that are complementary in that their operation requires energy will tend to decline even more, as households delay or forego purchases of energy-using durables. Contractionary tendencies could be strengthened by a hardening of interest rates due to the rise in prices and by investors turning extra cautious because of concerns about heightened uncertainty. Financial channel It is useful to distinguish the traditional channels of external adjustment, the trade channel, and the financial (or valuation) channel of adjustment. The trade channel works through changes in the quantities and prices of goods exported and imported; whereas the financial channel works through changes in external portfolio positions and asset prices. The financial channel could either cushion or exacerbate the effect of oil price increases on oilimporting countries external balances. A decrease in asset prices and dividends in oil-importing countries in response to an oil price increase will affect all asset owners, including residents of oil exporting countries. Conversely, asset prices in oil exporting countries will increase, again affecting all asset owners, including residents of oil importing countries. As a result, capital gains and income flows may blunt the impact of oil-price changes on the current account and on net foreign assets (NFA) changes. Bond and equity prices and exchange rates typically respond much faster than the prices and quantities of goods (and faster than portfolio positions). In practice, the response will depend on the precise configuration of countries portfolios, and the extent to which these portfolios can be rebalanced effectively. With certain portfolio configurations, the financial consequences of the shock could even completely offset the need for short-term external adjustment. A case in point is the US, which mostly has fixed income liabilities denominated in its own currency, while equity and foreign direct investment holdings are denominated in foreign currency. Using the Lane-Milesi-Ferretti net foreign asset data set, Kilian et. al (2007) show the presence of large and systematic valuation effects in response to oil shocks, not only for the United States, but also for other oilimporting economies and for oil exporters. Their estimates suggest that increased international 8

financial integration will tend to cushion the effect of oil shocks on NFA positions for major oil exporters and for the United States, but may amplify it for other oil importers. What should be the monetary policy response? Faced with an oil shock and higher prices, the monetary authorities have often tightened monetary policy. Bernanke, Gertler, and Watson (1997) have shown that the Federal Reserve, when faced with potential or actual inflationary pressures triggered by a positive oil price shock, responds by raising the interest rate, amplifying the decline in real output associated with oil price shocks. In assessing the effect of this policy response from vector autoregressive (VAR) models, Bernanke, Gertler, and Watson postulated a counterfactual in which the Federal Reserve holds the interest rate constant. In other words, the Fed is not responding to any of the effects of the oil price shock on the economy. They conclude that the Fed's systematic and anticipated response to oil price shocks is the main cause of the recessions that tend to follow oil price shocks and that these recessions could have been avoided (at the cost of higher inflation) by holding the interest rate constant. Bernanke, Gertler, and Watsons results have not remained unchallenged. Hamilton and Herrera (2004) showed that their estimates are sensitive to the choice of the VAR lag order. They also demonstrated that implementing a constant interest rate policy would have required policy changes so large to be unprecedented historically and hence not credible in light of the Lucas critique, a point acknowledged by Bernanke, Gertler, and Watson (2004). It is obvious that in a demand constrained economy the tendency of the central banks to tighten monetary policy when faced with an oil shock will result in further losses in output and employment though it can neutralise the cost-push effect of the shock on the price level. In figure 1, the shift in aggregate supply from AS1 to AS2 begins a chain of adjustment that creates an upward pressure on price level and a decline in real output. If the monetary policy is tightened, the aggregate demand curve will shift inwards from AD1 to AD2 and real output contract from y to y, which is more than what would have resulted had there been no monetary policy intervention. In fact, the shock results in a shift from one equilibrium to another so that policymakers are not confronted with a output-inflation trade-off or any danger of an unabated rise in prices. Unless a good case for the existence of a wage-price spiral can be made, oil price shocks would not be expected to cause sustained inflation.

Hence monetary (or fiscal) contraction for curbing prices cannot be an optimal response to an oil price shock in a demand deficient economy. Nakov and Pescatori (2010) demonstrate that a welfare-maximising central banker should not respond to increases in the price of oil. As long as the monetary policy regime is credible, the central bank may allow for drift in the price level without jeopardizing the objective of stable medium-term inflation. Since the 20032008 oil price shock reflected a shift in the real scarcity of resources, there is nothing a central bank could or should have done in response, beyond making sure that inflation expectations remained anchored by way of following say, an interest rate rule, in the face of inflationary pressures arising from both oil and industrial commodity prices is Kilians (2009) view.

10

V.

Macroeconomic Transmission Mechanism of International Oil Price Rise: The Indian Situation

Here we study the impact of an increase in international oil prices on Indian economy outlining the various transmission mechanisms. These mechanisms take into account some of the important macroeconomic relationships as relevant to the Indian economic context and the administered nature of domestic oil price in India.

The three broad channels through which the international oil prices have a deep impact on the economy a) Import Channel b) Price Channel c) Fiscal Channel

A)Import Channel India is a Net Oil Importing country , thus this leaves it susceptible to higher import Bill in the case of rise in international oil prices. Under the reasonable assumption of low price elasticity of demand for oil, ceteris paribus, the trade balance will worsen due to an increase in international oil price. Rise in inflation due to increase in oil prices means that the growth in real GDP is even lower. The compression in aggregate domestic demand dampens growth.

11

INDIAS FOREIGN TRADE - US DOLLARS

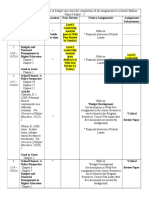

(US $ million) Year Oil 1990-91 1991-92 1992-93 1993-94 1994-95 1995-96 1996-97 1997-98 1998-99 1999-00 2000-01 2001-02 2002-03 2003-04 2004-05 2005-06 2006-07 2007-08 2008-09 2009-10 2010-11 2011-12 522.7 414.7 476.2 397.8 416.9 453.7 481.8 352.8 89.4 38.9 1869.7 2119.1 2576.5 3568.4 6989.3 11639.6 18634.6 28363.1 27547.0 28192.0 41480.0 55603.5 Exports Non-Oil 17622.5 17450.7 18061.0 21840.5 25913.6 31341.2 32987.9 34653.7 33129.3 36783.5 42690.6 41707.6 50142.9 60274.1 76546.6 91450.9 107779.5 134541.1 157748.0 150559.4 209656.2 249020.0 Total 18145.2 17865.4 18537.2 22238.3 26330.5 31794.9 33469.7 35006.4 33218.7 36822.4 44560.3 43826.7 52719.4 63842.6 83535.9 103090.5 126414.1 162904.2 185295.0 178751.4 251136.2 304623.5 Oil 6028.1 5324.8 6100.0 5753.5 5927.8 7525.8 10036.2 8164.0 6398.6 12611.4 15650.1 14000.3 17639.5 20569.5 29844.1 43963.1 56945.3 79644.5 93671.7 87135.9 105964.4 154905.9 Imports Non-Oil 18044.4 14085.7 15781.6 17552.7 22726.5 29149.5 29096.2 33320.5 35990.1 37059.3 34886.4 37413.0 43772.6 57579.6 81673.3 105202.6 128790.0 171794.7 210024.6 201237.0 263804.7 334511.5 Total 24072.5 19410.5 21881.6 23306.2 28654.4 36675.3 39132.4 41484.5 42388.7 49670.7 50536.5 51413.3 61412.1 78149.1 111517.4 149165.7 185735.2 251439.2 303696.3 288372.9 369769.1 489417.4 Oil -5505.4 -4910.1 -5623.8 -5355.7 -5510.9 -7072.0 -9554.4 -7811.2 -6309.2 12572.5 13780.4 11881.2 15063.0 17001.1 22854.8 32323.5 38310.7 51281.4 66124.7 58943.9 64484.4 99302.4 Trade Balance Non-Oil -421.9 3365.0 2279.4 4287.8 3187.1 2191.7 3891.7 1333.1 -2860.8 -275.8 7804.2 4294.6 6370.3 2694.5 -5126.7 13751.7 21010.5 37253.6 52276.6 50677.6 54148.5 85491.5 Total -5927.3 -1545.1 -3344.4 -1067.9 -2323.8 -4880.4 -5662.7 -6478.1 -9170.0 -12848.3 -5976.2 -7586.6 -8692.7 -14306.5 -27981.5 -46075.2 -59321.2 -88535.0 -118401.3 -109621.5 -118632.9 -184793.9

Note : Data for 2010-11 are revised and for 2011-12 are provisional. Source : Directorate General of Commercial Intelligence and Statistics.

In the figure explaining the linkages, the import channel is indicated by the link from international oil prices to current account balance to nominal GDP. Although managed float, the nominal exchange rate in India is observed to be determined solely by the capital account and not by the current account in the present Indian context. The second order adjustment to higher import bill and worsened trade balance occurs only through contraction in aggregate demand and decline in imports and it does not occur through movements in exchange rate (depreciation).

12

Finally, the slowdown in economic growth would subsequently reduce the demand for imports which, in turn, would partially mitigate the adverse impact of high international oil prices on trade balance.

B) Price Channel The price channel links the international prices to domestic inflation. For a typical developing country like India facing an oil price hike in the international market, an unhindered passthrough of oil price increase leads to a jump in the general price level on account of direct use of oil at higher prices plus increase in costs of production of final goods using oil as an input. Modelling the pass through of oil prices through an input-output system, Jha and Mundle (1987) estimated that in India if the administered prices of crude oil, gas and petroleum products increase by 7 per cent, the overall WPI increases by 1 per cent (i.e. the total elasticity to be 0.14). Recently the Reserve Bank of India (2011) has estimated that every 10 per cent increase in global crude prices, if fully passed through to domestic prices, could have a direct impact of 1 percentage point increase in overall WPI inflation and the total impact could be about 2 percentage points over time as input cost increases translate to higher output prices across sectors. Greater the share of fuel in total consumption basket, larger would be the influence of international commodity prices on inflation. In India, a large proportion of the international oil price increase has traditionally been absorbed by the government (and shared with public sector oil producing and retailing companies). The objectives for regulation of price of oil have been three-fold: (a) To protect the domestic economy from volatility in international oil prices (b) To provide merit goods to all households, e.g., clean cooking fuels like LPG, natural gas and Kerosene to replace use of biomass-based fuels such as firewood and dung (c) To protect poor consumers so that they may obtain kerosene (through PDS) and LPG at affordable prices. In the recent years, there has been a change in the oil pricing policy with a move towards market determined oil prices. The extent of price regulation varies across products in the oil basket, with minimum control existing for petrol and very little passthrough for LPG and kerosene The domestic price of oil is administered, which is essentially a policy decision, and thereby determines the degree of pass-through of the change in international prices to domestic oil prices. In figure explaining the linkages between the channels, the price channel is indicated by the link from international oil prices to increase in administered prices to WPI inflation C) Fiscal Channel The third channel of transmission of oil price shock considered here is the fiscal channel. In the absence of a complete pass-through, an international oil price increase will raise the subsidy on oil and therefore the revenue expenditure of the government. Furthermore, in India, the oil prices are subsidised, but they also generate substantial tax revenues both for the centre and the states. A rise in the international price of oil would entail higher revenue receipts because of an increase in ad valorem tax collections on oil and petroleum

13

products that would have to be netted out to arrive at the net addition to oil subsidy given by the government. Contribution of Petroleum Sector in Government Exchequer On the revenue side, the contribution of the petroleum sector to the exchequer of both Central and the State governments combined was 2.8 percent of GDP in 2009-10, with more than 60 percent share of the Central exchequer. The Central governments earning from this sector has been higher than the total revenue expenditure of the Central government in this sector. Although, the direct subsidy figures vary widely from source to source, the bulk of the revenue expenditure of the Central government on petroleum consists of petroleum subsidy. In 2009-10, the total revenue expenditure in petroleum was less than 0.4 percent of GDP. Even if we include the issue of special securities in lieu of subsidies to the oil marketing companies, it does not exceed 0.55 percent of GDP during 2009-10. Clearly, the contribution of this sector in exchequer has always been much higher than the sum of total revenue expenditure on petroleum and the petroleum bonds. Thus, in effect there is no net subsidy accruing to this sector. Also, it is important to note here that the total revenue expenditure has always been lower than the net profit (after tax) of the public sector oil companies including the upstream, downstream companies and the stand alone refineries barring the exceptional year of 2008-09, when the international price of oil touched historic peak

In terms of the transmission mechanism, the impact of an oil price change on sales tax collection would be much more direct in case of full pass-through and would be realised both through quantity and prices of imported oil (or the value of net imports). On the other hand, international oil price change will not directly affect the revenue generated from excise and customs duties because of the specific nature of these taxes, but only indirectly through its effect on the quantity of oil imported, which is a function of the level of economic activity. The fiscal channel as indicated in figure of linkages brings together both the revenue and expenditure effects of oil price change on the macro economy. There are two policy levers acting here: the administered price of oil (and hence subsidy) and the indirect tax rates on oil and petroleum products. The former determines the pass-through ratio that denotes how much of the change in international oil price change is to be passed on to domestic consumers as change in domestic oil price, and therefore the subsidy. The revenue from oil is a function of tax rates and the oil import quantity or value depending on the type of indirect tax. 14

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- Eco 1Dokumen25 halamanEco 1Sruti PujariBelum ada peringkat

- Effect of Oil Prices On EconomyDokumen10 halamanEffect of Oil Prices On EconomySaqib Mushtaq100% (1)

- Relationship between Crude Oil Prices & Inflation in IndiaDokumen17 halamanRelationship between Crude Oil Prices & Inflation in IndiaVilas p Gowda100% (1)

- Petrol Prices in IndiaDokumen24 halamanPetrol Prices in IndiaRakhi KumariBelum ada peringkat

- Task 7: Sreejith E M Jr. Research Analyst Intern 22FMCG30B15Dokumen23 halamanTask 7: Sreejith E M Jr. Research Analyst Intern 22FMCG30B15Sreejitha EmBelum ada peringkat

- An Effort To Devise A Strategy For Pricing of Petroleum ProductsDokumen12 halamanAn Effort To Devise A Strategy For Pricing of Petroleum ProductsHimanshu SharmaBelum ada peringkat

- Macroeconomic Effects of Petroleum Price HikeDokumen7 halamanMacroeconomic Effects of Petroleum Price Hikemd yousufBelum ada peringkat

- An Analytical View of Crude Oil Prices and Its Impact On Indian EconomyDokumen6 halamanAn Analytical View of Crude Oil Prices and Its Impact On Indian EconomyRohan SharmaBelum ada peringkat

- SubsidyDokumen22 halamanSubsidySam SaBelum ada peringkat

- Crude Oil Price, Monetary Policy and Output: Case of PakistanDokumen15 halamanCrude Oil Price, Monetary Policy and Output: Case of PakistanƁiLдL дhmed RajpootBelum ada peringkat

- MPRA Paper 104145Dokumen45 halamanMPRA Paper 104145Thùy LinhhBelum ada peringkat

- Impact of Oil Prices on Indian EconomyDokumen7 halamanImpact of Oil Prices on Indian EconomyMayank RajBelum ada peringkat

- Crude Oil Prices Impact on Pakistan InflationDokumen13 halamanCrude Oil Prices Impact on Pakistan InflationMuhammad Jahanzaib ShafiqueBelum ada peringkat

- Bom Project: Oil Price Decontrol inDokumen14 halamanBom Project: Oil Price Decontrol inRupali RoyBelum ada peringkat

- 6504 16164 1 PB PDFDokumen6 halaman6504 16164 1 PB PDFYew Wen KhangBelum ada peringkat

- Inflation: Alok Singh Ambesh Kumar SrivastavaDokumen24 halamanInflation: Alok Singh Ambesh Kumar Srivastavaambesh Srivastava100% (15)

- Aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaa A Aaa A Aaaaaaaaaaaa Aa A Aa A Aa Aaa A A A ADokumen3 halamanAaaaaaaaaaaaaaaa A Aaa A Aaaaaaaaaaaa Aa A Aa A Aa Aaa A A A AM Kashif RazaBelum ada peringkat

- Economic Outlook, Prospects, and Policy Challenges: Source: Central Statistics OfficeDokumen1 halamanEconomic Outlook, Prospects, and Policy Challenges: Source: Central Statistics OfficeSagargn SagarBelum ada peringkat

- Research ReportDokumen13 halamanResearch ReportShahroz AslamBelum ada peringkat

- RRL 3isDokumen6 halamanRRL 3isdevlinjoypabataoBelum ada peringkat

- Controls On PricesDokumen18 halamanControls On PricesSam SaBelum ada peringkat

- Factor Influencing Inflation Rate in The UAEDokumen4 halamanFactor Influencing Inflation Rate in The UAEDavid WilliamsBelum ada peringkat

- 1 - 38 - A416 - OmotoshoDokumen38 halaman1 - 38 - A416 - OmotoshomuhammadBelum ada peringkat

- Macro Factors Key Oil & Gas PricesDokumen9 halamanMacro Factors Key Oil & Gas Prices10manbearpig01Belum ada peringkat

- Oil PricingDokumen6 halamanOil PricingAnonymous mErRz7noBelum ada peringkat

- Organisation of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) International Energy Association (IEA)Dokumen3 halamanOrganisation of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) International Energy Association (IEA)Yogesh BohraBelum ada peringkat

- Monetary Policy Module 5Dokumen6 halamanMonetary Policy Module 5Idyelle Princess Salubo MalimbanBelum ada peringkat

- Oil Price Volatility and Its Impact On Economic Growth in PakistanDokumen15 halamanOil Price Volatility and Its Impact On Economic Growth in PakistanMUHAMMAD -Belum ada peringkat

- Factors Determineing Oil PriceDokumen9 halamanFactors Determineing Oil PriceRanu ChouhanBelum ada peringkat

- The Impact of Oil Sector On Saudi Arabian EconomyDokumen30 halamanThe Impact of Oil Sector On Saudi Arabian EconomyaliBelum ada peringkat

- It Also Reported That Sustained $10/ BBL Increase in The Price of Oil Would Lower World GDP by at Least 0.5 Per Cent in A YearDokumen18 halamanIt Also Reported That Sustained $10/ BBL Increase in The Price of Oil Would Lower World GDP by at Least 0.5 Per Cent in A YearAbhimanyu KumarBelum ada peringkat

- Final Prenstation of Economics by DynoDokumen30 halamanFinal Prenstation of Economics by DynolibradynoBelum ada peringkat

- 02 Rafay and Farid FINALDokumen14 halaman02 Rafay and Farid FINALShahid MushtaqBelum ada peringkat

- Oil ScarcityDokumen2 halamanOil ScarcityAngel ZainabBelum ada peringkat

- Term Paper Pakistan EconomyDokumen36 halamanTerm Paper Pakistan EconomyKhola ShahidBelum ada peringkat

- Research Proposal Oil02Dokumen9 halamanResearch Proposal Oil02Chirag RajuBelum ada peringkat

- Rising Fuel PricesDokumen2 halamanRising Fuel PricesstudentBelum ada peringkat

- Rising Fuel PricesDokumen2 halamanRising Fuel PricesununBelum ada peringkat

- Oil Price Impact on PakistanDokumen8 halamanOil Price Impact on PakistanMalik RohailBelum ada peringkat

- Oil Price Volatility Impact on Kenya's GDPDokumen9 halamanOil Price Volatility Impact on Kenya's GDPMUKUND BANSALBelum ada peringkat

- Oil Price DissertationDokumen7 halamanOil Price DissertationDoMyPaperForMeUK100% (1)

- Me Review Assignent - Arunima Viswanath - m200046msDokumen4 halamanMe Review Assignent - Arunima Viswanath - m200046msARUNIMA VISWANATHBelum ada peringkat

- Task 7 - Abin Som - 21FMCGB5Dokumen17 halamanTask 7 - Abin Som - 21FMCGB5Abin Som 2028121Belum ada peringkat

- Inflation in MalaysiaDokumen6 halamanInflation in MalaysiaPrince DesperadoBelum ada peringkat

- Impact of Oil Prices On Pakistan's EconomyDokumen8 halamanImpact of Oil Prices On Pakistan's Economydevilsprey_87Belum ada peringkat

- Effects of Rising Oil Prices on Global EconomyDokumen20 halamanEffects of Rising Oil Prices on Global EconomyJunaid MughalBelum ada peringkat

- Kaushik & Indranil (2001)Dokumen8 halamanKaushik & Indranil (2001)zati azizBelum ada peringkat

- Petroleum Subsidies: A Case Against SubsidiesDokumen25 halamanPetroleum Subsidies: A Case Against Subsidiesanmol_bajajBelum ada peringkat

- Proposal Draft 2Dokumen9 halamanProposal Draft 2ashfBelum ada peringkat

- Petroleum Economics Assignemnt No.1Dokumen3 halamanPetroleum Economics Assignemnt No.1Saad FaheemBelum ada peringkat

- Inflation-Pattern Over 1991-2011 Reasons and Impact (India)Dokumen38 halamanInflation-Pattern Over 1991-2011 Reasons and Impact (India)Vinayak PadwalBelum ada peringkat

- Vietnam vegetable oil tariff protects domestic producersDokumen7 halamanVietnam vegetable oil tariff protects domestic producersPreet kotadiyaBelum ada peringkat

- Report On Edible Oil PriceDokumen19 halamanReport On Edible Oil PriceRakibul RonyBelum ada peringkat

- Economics of rising fuel prices: Impacts and solutionsDokumen6 halamanEconomics of rising fuel prices: Impacts and solutionsTwinkle MounamiBelum ada peringkat

- Lecture 1 - Energy Reforms in IndiaDokumen15 halamanLecture 1 - Energy Reforms in IndiaAakansha DBelum ada peringkat

- Lecture 1 - Energy Reforms in IndiaDokumen15 halamanLecture 1 - Energy Reforms in IndiaAakansha DBelum ada peringkat

- Economic Slowdown and Macro Economic PoliciesDokumen38 halamanEconomic Slowdown and Macro Economic PoliciesRachitaRattanBelum ada peringkat

- Business Economics: Business Strategy & Competitive AdvantageDari EverandBusiness Economics: Business Strategy & Competitive AdvantageBelum ada peringkat

- New ECA Applicants (Form)Dokumen3 halamanNew ECA Applicants (Form)Pramesh ChandBelum ada peringkat

- Avatar'13 Concept DocumentDokumen4 halamanAvatar'13 Concept DocumentPramesh ChandBelum ada peringkat

- Icici Imobile - Mobile Banking at Its BestDokumen9 halamanIcici Imobile - Mobile Banking at Its BestPramesh ChandBelum ada peringkat

- GE - Decision SheetDokumen1 halamanGE - Decision SheetPramesh ChandBelum ada peringkat

- RALRDokumen2 halamanRALRPramesh ChandBelum ada peringkat

- Presented by : Ronak Vijayvergia Sanjay Kumar Sahoo Sadu Chaitanya Reddy Siba VinithDokumen17 halamanPresented by : Ronak Vijayvergia Sanjay Kumar Sahoo Sadu Chaitanya Reddy Siba VinithPramesh ChandBelum ada peringkat

- Presented by : Ronak Vijayvergia Sanjay Kumar Sahoo Sadu Chaitanya Reddy Siba VinithDokumen17 halamanPresented by : Ronak Vijayvergia Sanjay Kumar Sahoo Sadu Chaitanya Reddy Siba VinithPramesh ChandBelum ada peringkat

- LakDokumen11 halamanLakPramesh ChandBelum ada peringkat

- Organizational Culture Of: Based On The Factors That Influencing NOKIA To Become A Successful OrganizationDokumen11 halamanOrganizational Culture Of: Based On The Factors That Influencing NOKIA To Become A Successful OrganizationPramesh ChandBelum ada peringkat

- Internship Application Form: You Can Submit This Information in The Following FormatsDokumen2 halamanInternship Application Form: You Can Submit This Information in The Following FormatsPramesh ChandBelum ada peringkat

- Costs For The ServiceDokumen2 halamanCosts For The ServicePramesh ChandBelum ada peringkat

- LakshyaDokumen15 halamanLakshyaPramesh ChandBelum ada peringkat

- Annual Report 10 11Dokumen117 halamanAnnual Report 10 11Aditya RanaBelum ada peringkat

- HR Q5e6tew4uestion Bank 2012 PDFDokumen2 halamanHR Q5e6tew4uestion Bank 2012 PDFPramesh ChandBelum ada peringkat

- Answer 3Dokumen2 halamanAnswer 3Pramesh ChandBelum ada peringkat

- Symbiosis Centre For Management & HRDDokumen5 halamanSymbiosis Centre For Management & HRDPramesh ChandBelum ada peringkat

- Marquest V5.0: Selected TeamsDokumen3 halamanMarquest V5.0: Selected TeamsPramesh ChandBelum ada peringkat

- HR Q5e6tew4uestion Bank 2012 PDFDokumen2 halamanHR Q5e6tew4uestion Bank 2012 PDFPramesh ChandBelum ada peringkat

- Auto Auto CompDokumen94 halamanAuto Auto Compsivakumar118Belum ada peringkat

- A ReviewDokumen17 halamanA ReviewPramesh ChandBelum ada peringkat

- Chap 11 WEDokumen11 halamanChap 11 WEPramesh ChandBelum ada peringkat

- Table ShopkeeperDokumen1 halamanTable ShopkeeperPramesh ChandBelum ada peringkat

- KolaveriDokumen5 halamanKolaveriPramesh ChandBelum ada peringkat

- IT SectorDokumen12 halamanIT SectorPramesh ChandBelum ada peringkat

- Team Performance AssessmentDokumen20 halamanTeam Performance Assessmentfrankrl86Belum ada peringkat

- Ifrs Usgaap NotesDokumen38 halamanIfrs Usgaap Notesaum_thai100% (1)

- Portage Public Schools 19.20 BudgetDokumen10 halamanPortage Public Schools 19.20 BudgetKayla MillerBelum ada peringkat

- Risk ManagementDokumen16 halamanRisk ManagementMarieBelum ada peringkat

- FINAL EXAM REVIEWDokumen6 halamanFINAL EXAM REVIEWgamerfoxyBelum ada peringkat

- Assignment Managerial FinanceDokumen29 halamanAssignment Managerial FinancesdfdsfBelum ada peringkat

- Public Finance and Taxation IntroductionDokumen35 halamanPublic Finance and Taxation IntroductionMetoo ChyBelum ada peringkat

- Audit & Compliance Department: General Guidelines & Original Bill Policy Check ListDokumen2 halamanAudit & Compliance Department: General Guidelines & Original Bill Policy Check ListFarooq MaqboolBelum ada peringkat

- Week Reading Discussion Peer Review Future Assignments Assignment SubmissionsDokumen3 halamanWeek Reading Discussion Peer Review Future Assignments Assignment SubmissionsUchenduOkekeBelum ada peringkat

- The Average Inflation Rate For 2009 Was 3.2 Percent Compared With 9.3 Percent in 2008, and Is Projected atDokumen5 halamanThe Average Inflation Rate For 2009 Was 3.2 Percent Compared With 9.3 Percent in 2008, and Is Projected atCharlene LeynesBelum ada peringkat

- New Liquidation FormDokumen51 halamanNew Liquidation FormPergie Acabo TelarmaBelum ada peringkat

- Revised Guidelines for Utilizing the Agricultural Competitiveness Enhancement FundDokumen44 halamanRevised Guidelines for Utilizing the Agricultural Competitiveness Enhancement FundrengabBelum ada peringkat

- Petroskills Economics of Worldwide Petroleum Production BookDokumen20 halamanPetroskills Economics of Worldwide Petroleum Production BooksaadalamBelum ada peringkat

- Costing Formulas PDFDokumen86 halamanCosting Formulas PDFsubbu100% (3)

- Guiding Principles of Sound Management Fiscal SystemsDokumen32 halamanGuiding Principles of Sound Management Fiscal SystemsMark Jayson Yamson PinedaBelum ada peringkat

- Project Cost Management Project Cost Management Determine Project Budget Determine Project BudgetDokumen36 halamanProject Cost Management Project Cost Management Determine Project Budget Determine Project BudgetFahad MushtaqBelum ada peringkat

- Financial ManagementDokumen254 halamanFinancial Managementkimringine50% (2)

- Government Accounting Manual For National Government Agencies Volume IDokumen27 halamanGovernment Accounting Manual For National Government Agencies Volume IKath Hidalgo100% (1)

- L 3 QCF Cnl99 - Unit 2 - BR - Assignment BriefDokumen12 halamanL 3 QCF Cnl99 - Unit 2 - BR - Assignment BriefRajiv VyasBelum ada peringkat

- TOP 40 SAP FICO TRANSACTION CODESDokumen3 halamanTOP 40 SAP FICO TRANSACTION CODESmittalmistry629931100% (1)

- Chapter 09 & 10 Engineering Economic Analysis and Profitability Analysis - ModifiedDokumen42 halamanChapter 09 & 10 Engineering Economic Analysis and Profitability Analysis - ModifiedIbrahim Al-HammadiBelum ada peringkat

- Oil and Natural Gas Corporation LTDDokumen92 halamanOil and Natural Gas Corporation LTDPreeti BhaskarBelum ada peringkat

- Cost AccountingDokumen197 halamanCost AccountingKenadid Ahmed OsmanBelum ada peringkat

- Cebu Committee Approves Ronda Municipality BudgetDokumen3 halamanCebu Committee Approves Ronda Municipality BudgetttunacaoBelum ada peringkat

- How Large Is Its Cyclically Adjusted Budget Deficit HowDokumen4 halamanHow Large Is Its Cyclically Adjusted Budget Deficit HowCharlotteBelum ada peringkat

- Practice MCQDokumen6 halamanPractice MCQsaiBelum ada peringkat

- 092514the Star NewsDokumen38 halaman092514the Star NewsThe Star NewsBelum ada peringkat

- Ecs2602 MCQ Testbank PDFDokumen74 halamanEcs2602 MCQ Testbank PDFPaula kelly100% (1)

- Eric Woon Kim Thak: Education/QualificationDokumen1 halamanEric Woon Kim Thak: Education/Qualificationeric woonBelum ada peringkat

- Chapter 14Dokumen19 halamanChapter 14Yuxuan Song100% (1)