Spiral Curriculum

Diunggah oleh

Rhan AlcantaraHak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Spiral Curriculum

Diunggah oleh

Rhan AlcantaraHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Modern educational theories are as abundant as the theorists proposing them, so it is often difficult to determine which theories are

worthy of consideration. One of the more common and important theories comes from Jerome Bruner and teaches an intuitively appealing approach to education. Bruner's model of the spiral curriculum is an element of educational philosophy suggesting that students should continually return to basic ideas as new subjects and concepts are added over the course of a curriculum. This is done in order to solidify understanding over periodic intervals. The idea behind the method is for students really to learn, rather than simply memorizing equations to pass a test.The spiral curriculum theory revolves around the understanding that human cognition evolved in a step-by-step process of learning, which relied on environmental interaction and experience to form intuition and knowledge. In simpler terms, one learns best through the repeated experience of a concept. Over the course of development, behaviors and pieces of knowledge are reinforced by outcomes, and Bruner's model of the spiral curriculum seeks to match that learning process in the classroom. The concept goes along with Bruner's theory of discovery learning, which posits that students learn best by building on their current knowledge. Bruner also emphasized learning motivated by interest in the material, rather than by objective means like grades or punishments. Many of the ideas proposed by Bruner were met with resistance by fearful conservatives and religious types because they encouraged questioning aspects of society like morality and belief systems. The most unpopular aspect of Bruner's theories, however, was in regard to the evolutionary foundation from which the theory was drawn. While the theory happens to find a basis in evolution, it is ultimately about common experiences observed in daily life. Bruner proposed the basic theory of spiral learning, and the ramifications of this theory continue to impact the education process to this very day.

he concept of a spiral curriculum has changed the way I teach. I suspect that the concept will change the way most teachers teach before too much longer. And special needs students will benefit from that. Let me compare a spiral curriculum to the more traditional approach to teaching that people are used to. The basic idea behind the traditional approach is that the time has come for something: fractions, gerunds, state capitals, the Third Law of Thermodynamics - whatever. Because the time has come, we're going to learn it. Maybe that means we're going to memorize it (like with state capitals). Maybe that means we're going to develop a skill with it (like the addition of fractions with like denominators). Maybe that means we're going to grasp how it affects us. But whatever it means, the time is now - for everyone. We're going to work on it for a while. The kids are going to learn it now. And then we're going to move on to the next thing that the time has come for... In contrast, a spiral curriculum begins with the assumption that children are not always ready to learn something. Readiness to learn is at the core of a spiral curriculum. And instead of focusing for relatively long periods of time on some narrow topic whose time has come, a spiral curriculum tries to expose students to a wide varies of ideas over and over ago. For a select few, the time for gerunds and infinitives has already arrived by the second grade. And for a few, algebra and geometry make perfect sense by grade three. A spiral curriculum, by moving in a circular pattern from topic to topic within a field like, say, math, seeks to catch kids when they first become ready to learn something and pick up

the other kids, the ones not ready to learn yet, later - the next time we spiral around to that topic. Why isn't a spiral curriculum a circular curriculum? Because it doesn't stay at the same difficulty level as time goes by.... It is with math that I became involved in a spiral curriculum. My school district began recently implementing a curriculum developed at the University of Chicago called Everyday Math. From the very early grades students are introduced to ideas from algebra, geometry, statistics, measurement, patterns, and so on. The challenge for the teacher? Simple: stay on track. The first time you try and explain what a variable is, no one gets it. You spend the day that the book says to on it and you move on. And that is hard for someone from a traditional background. Looking at a group of kids and saying, "No one understood. Some of them will get it next time..." is hard for someone from a traditional teaching background. But there will be a next time. And a next time after that. So if Billy or Suzie isn't ready for converting improper fractions to mixed numbers this week, right now, that's okay.

The medical spiral curriculum Many modern medical training institutions have adapted Jerome Bruner's [7] concept of the "spiral curriculum," and use it in their medical teaching [8-13]. Also sometimes referred to as the "spiral of learning" [14] the spiral curriculum is based upon "an iterative revisiting of topics, subjects or themes throughout the course. A spiral curriculum is not simply the repetition of a topic taught. It requires also the deepening of it, with each successive encounter building on the previous one [10]." Levels of difficulty and sophistication are increased, new learning is related to previous learning, and the students' competency is increased [10]. To provide added value, whilst maintaining the continuity in the spiral, "vertical themes" [2] or "golden threads" [15] are often developed throughout the curriculum. The spiral is practiced in different ways at different institutions, but, essentially it recognises that courses in an undergraduate medical degree are components of a larger whole, and that, in addition to fitting together like pieces of a puzzle, they build up progressively, adding to student learning by building upon previously acquired knowledge. There is an assumption made,

however that previously learned material is retained and built upon: the spiral is not solely a repository for revision material. The university of Cape Town The University of Cape Town's (UCT) Faculty of Health Sciences currently uses an LMS (WebCT) to support its medical curriculum [16-18]. The medical degree is divided into 12 semesters across 6 years. The first 2 1/2 years follow the Problem-Based Learning (PBL) approach, while the rest of the degree resembles the more traditional clinical rotation years. In their first year, students also take a 2-semester multi-professional course [19]. The Faculty emphasises the concept of the spiral in the medical curriculum, and highlights it in documentation, aimed at both staff and students. For example, the Web site of Obstetrics and Gynaecology discusses the spiral curriculum [20], and the student handbook reinforces this by saying that the block "builds on the introduction provided in Semester 6 [3rd year] programme and forms part of a progressive spiral curriculum that runs through to the final year [21]." In addition, official curriculum documents discuss the use of the spiral [22], and educators in the faculty have described it in published papers [23]. There is also a great deal of informal reference to the spiral some assessments make specific reference to the "spiral-based problem-based learning curriculum," and staff and students refer to the spiral in the LMS discussion boards. One such posting, by a student, complained that a section of the course had been trimmed, and, as a result, "spiral of learning won't develop fully." Previous studies Probably because allowing students access to previous courses is not standard practice, no literature on the reasons for student usage of previous course material could be found. There are, however, some general figures and some evidence of institutional and students' difficulties when disengaging from their online course environment [24-27]. In a previous study [28], one of the authors (KM) examined medical students' access to previous courses, and found that an average of 69% of students had accessed the previous courses after

they had officially ended, and that access continued for several years into the degree (albeit as low as 7% of the class). That study, however, did not tell anything about the students' activities in those courses, and whether or not the students were aware of their activities as participating in a spiral curriculum. The problem There is little doubt that medical education is dynamic; new innovations lead to new course developments, varied teaching technologies and novel assessment procedures. Courses rarely stand still and frequently change year upon year. Although little is known of its degree, it is not unusual for course material to be replaced year upon year, often with the replacement of previous online courses in the LMS. How this then interacts or even interferes with the spiral curriculum is open to debate: the spiral's revisiting of previous material implies that students need to refer to previous work, but the previous work may no longer exist, often substituted by new material or material relevant only to the present student. To determine the scope of the problem and attempt a solution, we need to answer two questions: Firstly, does the spiral curriculum really exist? While the spiral curriculum exists as an institutional policy and goal, and the curriculum map will tell us that the staff are revisiting and deepening the information, how do we know that the students are seeing and experiencing it as such, rather than merely seeing the later years as completely new and unrelated material? Is there a "hidden curriculum" [29] in which we believe that we have a successful approach, yet which is completely ignored by teaching staff and students, as "they find themselves unexpectedly trapped by grades (and grading), competition for success and the rewards that accompany it, and institutionalisation [29]." As Lowrie warns: "It is not enough merely to define the teaching content of a course. What teachers teach and what students learn may not be the same [30]." Reference has already been made to a student's posting regarding the spiral, but this might be an isolated incident. If the spiral exists in the majority of the students' minds, there would be ample evidence that they are actually revisiting previous materials, and for the purposes of developing the spiral as they approach new material later in their degree.

To answer this question, we aimed to determine the reasons for students' returning to the previous courses, and the benefits they perceived in having access to the previous courses. This information would be used to judge the students' awareness of the spiral curriculum and the value they attached to having the material available. Secondly, by implication, if the LMS is to support the spiral curriculum, what does this say of the practice of archiving and replacing previous courses in the LMS? This paper attempts to answer the two questions by closely investigating student activities in courses that allow them to access previous materials in the LMS. The answers will have implications for other institutions that have spiral curricula and LMSs supporting their face-toface activities.

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- What Are The Implications of Learning Theories For Classroom TeachersDokumen2 halamanWhat Are The Implications of Learning Theories For Classroom TeacherszieryBelum ada peringkat

- Lesson 2 Recalling Experiences: Type of Stories Why You Liked? Why You Disliked? Animal StoriesDokumen6 halamanLesson 2 Recalling Experiences: Type of Stories Why You Liked? Why You Disliked? Animal StoriesMaricel Viloria100% (1)

- Learning Style Inventory DRDokumen4 halamanLearning Style Inventory DRapi-458312837Belum ada peringkat

- Direct, Purposeful ExperiencesDokumen25 halamanDirect, Purposeful ExperiencesJason Bautista100% (1)

- Writing ObjectivesDokumen13 halamanWriting ObjectivesAlan RaybertBelum ada peringkat

- Theories J Rationale and Evidence Supporting MTB-MLE Developmental Learning TheoriesDokumen2 halamanTheories J Rationale and Evidence Supporting MTB-MLE Developmental Learning TheoriesChanie Lynn MahinayBelum ada peringkat

- Math ExercisesDokumen7 halamanMath ExercisesFilma Poliran SumagpaoBelum ada peringkat

- DLP 2nd To 4thDokumen13 halamanDLP 2nd To 4thRowena Anderson100% (1)

- ELED-107-Module Unit-I-Lesson-2Dokumen4 halamanELED-107-Module Unit-I-Lesson-2ethan philasiaBelum ada peringkat

- Bloom's Taxonomy ExplainedDokumen20 halamanBloom's Taxonomy Explainedhazreen othmanBelum ada peringkat

- Worksheet 3 Module 1.Dokumen2 halamanWorksheet 3 Module 1.April RodriguezBelum ada peringkat

- Global Literacy's ImportanceDokumen3 halamanGlobal Literacy's ImportanceElma SintosBelum ada peringkat

- MOTHER TONGUE EDUCATION REVIEWDokumen2 halamanMOTHER TONGUE EDUCATION REVIEWJuliet Marie Mijares100% (1)

- Demonstration Lesson Plan For Multigrade ClassesDokumen9 halamanDemonstration Lesson Plan For Multigrade ClassesIrish Cheska EspinosaBelum ada peringkat

- CEBU TECHNOLOGICAL UNIVERSITY College of EducationDokumen3 halamanCEBU TECHNOLOGICAL UNIVERSITY College of Educationcaryl lawas100% (1)

- Components of Physical Education and Health in The Elementary GradesDokumen11 halamanComponents of Physical Education and Health in The Elementary GradesMaria Angelica Mae BalmedinaBelum ada peringkat

- Erin Kyle WK 6 Metacognitive Lesson PlanDokumen3 halamanErin Kyle WK 6 Metacognitive Lesson Planapi-357041840100% (1)

- Reviewer CTPDokumen4 halamanReviewer CTPCjls KthyBelum ada peringkat

- Comparative StudiesDokumen66 halamanComparative StudiesJasmin CaballeroBelum ada peringkat

- Comparing Adjectives Lesson for StudentsDokumen9 halamanComparing Adjectives Lesson for StudentsMarbie Centeno OcampoBelum ada peringkat

- GED 109 EXAMS-WPS OfficeDokumen20 halamanGED 109 EXAMS-WPS OfficeShaina Joy Moy SanBelum ada peringkat

- 1.1 A Five Dimensional Framework For Authentic AssessmentDokumen23 halaman1.1 A Five Dimensional Framework For Authentic AssessmentCường Nguyễn MạnhBelum ada peringkat

- Who Is John LockeDokumen5 halamanWho Is John LockeAngelica LapuzBelum ada peringkat

- Integrating Learning Styles and Multiple IntelligencesDokumen9 halamanIntegrating Learning Styles and Multiple IntelligencesJefferson PlazaBelum ada peringkat

- PunctuationsDokumen5 halamanPunctuationsPrincess De VegaBelum ada peringkat

- Decoding Descriptive AdjectivesDokumen15 halamanDecoding Descriptive AdjectivesKathleen Hipolito YunBelum ada peringkat

- Flexible Learning Options for All StudentsDokumen3 halamanFlexible Learning Options for All StudentsJunelyn Gapuz VillarBelum ada peringkat

- Curriculum Evaluation Through Learning AssessmentDokumen35 halamanCurriculum Evaluation Through Learning AssessmentJenechielle LopoyBelum ada peringkat

- The Role of ComputersDokumen21 halamanThe Role of ComputersGarth GreenBelum ada peringkat

- Benefits of Play in Childhood Cognitive DevelopmentDokumen1 halamanBenefits of Play in Childhood Cognitive DevelopmentJaphet BagsitBelum ada peringkat

- LAS Math1 Q1 W5 - (M1NS-Id-5)Dokumen14 halamanLAS Math1 Q1 W5 - (M1NS-Id-5)Nelsie MayBelum ada peringkat

- Review of Related LiteratureDokumen23 halamanReview of Related LiteratureZhelBelum ada peringkat

- Strategies for Inspiring Student EngagementDokumen10 halamanStrategies for Inspiring Student Engagementjanang janangBelum ada peringkat

- AiL2 Group 2 ReportDokumen18 halamanAiL2 Group 2 ReportSharlene Cecil PagoboBelum ada peringkat

- Enhanced Math CG PDFDokumen351 halamanEnhanced Math CG PDFPearl CharisseBelum ada peringkat

- En6G-Iig-7.3.1 En6G-Iig-7.3.2: Test - Id 32317&title Prepositional PhrasesDokumen15 halamanEn6G-Iig-7.3.1 En6G-Iig-7.3.2: Test - Id 32317&title Prepositional PhrasesKenia Jolin Dapito EnriquezBelum ada peringkat

- Detailed Lesson Plan in Module 19Dokumen6 halamanDetailed Lesson Plan in Module 19Sheejah SilorioBelum ada peringkat

- Kent Marianito-WPS OfficeDokumen12 halamanKent Marianito-WPS OfficeKent Andojar MarianitoBelum ada peringkat

- My Final Lesson PlanDokumen4 halamanMy Final Lesson PlanMaria Rose Giltendez - BartianaBelum ada peringkat

- A Detailed Lesson Plan in Grade II EnglishDokumen6 halamanA Detailed Lesson Plan in Grade II EnglishAxel VirtudazoBelum ada peringkat

- Theories On Factors Affecting Motivation: Prepared By: Jenny Jane F. Perez Rolando Jose RamosDokumen15 halamanTheories On Factors Affecting Motivation: Prepared By: Jenny Jane F. Perez Rolando Jose RamosLysander GarciaBelum ada peringkat

- Lesson Plan For Final Demo - March 6,2018Dokumen3 halamanLesson Plan For Final Demo - March 6,2018ARJELYN DATANGBelum ada peringkat

- Learner Development Theories ReviewDokumen5 halamanLearner Development Theories ReviewBena Joy AbriaBelum ada peringkat

- Lets ReviewDokumen11 halamanLets ReviewMarino De Manuel BartolomeBelum ada peringkat

- Lesson 1. Mathematics and Mathematics Curriculum in The Primary GradesDokumen5 halamanLesson 1. Mathematics and Mathematics Curriculum in The Primary GradesKaren ArmentaBelum ada peringkat

- This Study Resource Was: Multigrade Lesson Plan IN ScienceDokumen3 halamanThis Study Resource Was: Multigrade Lesson Plan IN ScienceCrescent AnnBelum ada peringkat

- Organizing The Physical Envirinment Managing STudents BehaviorDokumen7 halamanOrganizing The Physical Envirinment Managing STudents Behaviorrruanes02Belum ada peringkat

- Lesson 1: The Curriculum Guide ObjectivesDokumen48 halamanLesson 1: The Curriculum Guide ObjectivesGodwin Jerome ReyesBelum ada peringkat

- Lesson 5 - RhythmicDokumen8 halamanLesson 5 - RhythmicRochel PalconitBelum ada peringkat

- 5e Lesson PlanDokumen3 halaman5e Lesson Planapi-257169466Belum ada peringkat

- Wikis and BlogsDokumen13 halamanWikis and BlogsTrixia Ann ColibaoBelum ada peringkat

- Research Connection Read A Research or Study Related To Students' Diversity in Motivation. Fill Out The Matrix BelowDokumen4 halamanResearch Connection Read A Research or Study Related To Students' Diversity in Motivation. Fill Out The Matrix BelowNog YoBelum ada peringkat

- Astronomy - : The Goals and Scope of AstronomyDokumen7 halamanAstronomy - : The Goals and Scope of AstronomyMarjon SubitoBelum ada peringkat

- Sir AñoDokumen12 halamanSir AñoMa Eloisa Juarez BubosBelum ada peringkat

- Guimaras State College: States, Universities and Colleges Mclain, Buenavista, GuimarasDokumen17 halamanGuimaras State College: States, Universities and Colleges Mclain, Buenavista, GuimarasJamaica Roie T. RicablancaBelum ada peringkat

- TS JenielynCanar DLP OutputDokumen5 halamanTS JenielynCanar DLP OutputJenielyn CanarBelum ada peringkat

- Students Diversity in MotivationDokumen1 halamanStudents Diversity in MotivationLeonivel Ragudo100% (1)

- Curriculum and Its DevelopementDokumen31 halamanCurriculum and Its DevelopementDherick RaleighBelum ada peringkat

- Curriculum NotesDokumen21 halamanCurriculum Notescacious mwewaBelum ada peringkat

- Unit I The Teacher and The School CurriculumDokumen13 halamanUnit I The Teacher and The School CurriculumJimuel AntonioBelum ada peringkat

- Agricultural Revolution: Historical Development of BiotechnologyDokumen24 halamanAgricultural Revolution: Historical Development of BiotechnologyRhan AlcantaraBelum ada peringkat

- History of BiotechnologyDokumen90 halamanHistory of BiotechnologyrahuldtcBelum ada peringkat

- Lesson Plan Template For CotDokumen2 halamanLesson Plan Template For CotRhan Alcantara100% (4)

- Biotechnology Grade 8 2019-2020 Ms. April Estrella Vale: Subject Grade Level School Year Teacher Subject DescriptionDokumen5 halamanBiotechnology Grade 8 2019-2020 Ms. April Estrella Vale: Subject Grade Level School Year Teacher Subject DescriptionRhan AlcantaraBelum ada peringkat

- Lesson Plan Template For CotDokumen2 halamanLesson Plan Template For CotRhan AlcantaraBelum ada peringkat

- Biology Test Cell StructureDokumen7 halamanBiology Test Cell Structuredee.aira29550% (1)

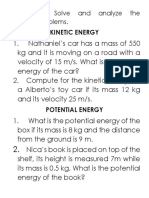

- Kinetic and Potential Energy ProblemsDokumen2 halamanKinetic and Potential Energy ProblemsRhan AlcantaraBelum ada peringkat

- CriteriaDokumen1 halamanCriteriaRhan AlcantaraBelum ada peringkat

- UK Chemistry Olympiad Round 1 Mark Scheme 2016Dokumen11 halamanUK Chemistry Olympiad Round 1 Mark Scheme 2016Rhan AlcantaraBelum ada peringkat

- MechanicsDokumen5 halamanMechanicsRhan AlcantaraBelum ada peringkat

- Dolly: The Science Behind Cloning's Most Famous SheepDokumen7 halamanDolly: The Science Behind Cloning's Most Famous SheepRhan AlcantaraBelum ada peringkat

- SKDFHVJN, C: Alakdsal CX, MN, ADokumen1 halamanSKDFHVJN, C: Alakdsal CX, MN, ARhan AlcantaraBelum ada peringkat

- CNBP 027038Dokumen9 halamanCNBP 027038Camha NguyenBelum ada peringkat

- SKDFHVJN, C: Alakdsal CX, MN, ADokumen1 halamanSKDFHVJN, C: Alakdsal CX, MN, ARhan AlcantaraBelum ada peringkat

- Ann 123 OuncementDokumen1 halamanAnn 123 OuncementRhan AlcantaraBelum ada peringkat

- A AaaaaaaaaaaaDokumen1 halamanA AaaaaaaaaaaaRhan AlcantaraBelum ada peringkat

- Asian Countries AfghanistanDokumen1 halamanAsian Countries AfghanistanRhan AlcantaraBelum ada peringkat

- Aaaaaaaaaaaaaaa AaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaDokumen1 halamanAaaaaaaaaaaaaaa AaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaRhan AlcantaraBelum ada peringkat

- Observation SheetDokumen5 halamanObservation SheetBeulah Asilo Viola100% (6)

- Ict ReactionDokumen2 halamanIct ReactionPaul Aldrin OlaeraBelum ada peringkat

- RHGP Intro For NTO1TDokumen20 halamanRHGP Intro For NTO1TAlbinMae Caroline Intong-Torres Bracero-Cuyos100% (1)

- 2022-2023 Classroom Procedures and ExpectationsDokumen3 halaman2022-2023 Classroom Procedures and Expectationsapi-290946677Belum ada peringkat

- Monitoring ChecklistDokumen8 halamanMonitoring ChecklistElenor May Chantal MessakaraengBelum ada peringkat

- Basava SOPDokumen4 halamanBasava SOPRajiv Ranjan DundaBelum ada peringkat

- A Thesis - PadmaningtyasDokumen303 halamanA Thesis - PadmaningtyasNgurah ArikBelum ada peringkat

- Instructional Planning Detailed Lesson Plan (DLP) FormatDokumen32 halamanInstructional Planning Detailed Lesson Plan (DLP) FormatShyrra AndersonBelum ada peringkat

- Als Ila 2020Dokumen36 halamanAls Ila 2020JULIA PoncianoBelum ada peringkat

- Final Long Paper - School Readiness AssessmentDokumen13 halamanFinal Long Paper - School Readiness Assessmentapi-258682603Belum ada peringkat

- Ad Copy Editor Writer in Skokie IL Resume Kurt DiClementiDokumen2 halamanAd Copy Editor Writer in Skokie IL Resume Kurt DiClementiKurtDiClementiBelum ada peringkat

- Advance Educational Planning and Management-Issues and Challenges in Improving Quality EducationDokumen3 halamanAdvance Educational Planning and Management-Issues and Challenges in Improving Quality EducationNikki Joya - CandelariaBelum ada peringkat

- Globalization & Asean Integration: Presented By: Renalyn B. GalgoDokumen36 halamanGlobalization & Asean Integration: Presented By: Renalyn B. GalgoLalaine GalgoBelum ada peringkat

- Internal Quality Assurance Cell (IQAC) and Submission of Annual Quality Assurance Report (AQAR) by Accredited InstitutionsDokumen33 halamanInternal Quality Assurance Cell (IQAC) and Submission of Annual Quality Assurance Report (AQAR) by Accredited InstitutionsrupalBelum ada peringkat

- TimetableDokumen7 halamanTimetableJohn Murphy AlmarioBelum ada peringkat

- DISS Week 1 Nov7 11 2022Dokumen14 halamanDISS Week 1 Nov7 11 2022Maricris AtienzaBelum ada peringkat

- Master Teacher KRAs and MOVsDokumen5 halamanMaster Teacher KRAs and MOVsSimonette CastrenceBelum ada peringkat

- Mary Mount School Standards-Based Improvement PlanDokumen39 halamanMary Mount School Standards-Based Improvement PlanTeàcher Peach100% (4)

- Examples and Situations. 1. Biographical Jigsaw ActivityDokumen2 halamanExamples and Situations. 1. Biographical Jigsaw ActivityArnold CimzBelum ada peringkat

- Synthesis Chapter 6 Philosophy and Aims of EducationDokumen7 halamanSynthesis Chapter 6 Philosophy and Aims of EducationRosanna Arias ManzuetaBelum ada peringkat

- Gordano School - Published ReportDokumen12 halamanGordano School - Published ReportOz GoffBelum ada peringkat

- Guru Gobind Singh Indraprastha University: (Sponsored by Vasavi Academy of Education)Dokumen12 halamanGuru Gobind Singh Indraprastha University: (Sponsored by Vasavi Academy of Education)ramu023Belum ada peringkat

- CHED strategic plan guides PH higher edDokumen18 halamanCHED strategic plan guides PH higher edPeter Jonas DavidBelum ada peringkat

- Reading Intervention PROJECT PROPOSAL-4P'sDokumen7 halamanReading Intervention PROJECT PROPOSAL-4P'sRyan S. EbronBelum ada peringkat

- HUMSS - Culminating Activity CG - 1 PDFDokumen3 halamanHUMSS - Culminating Activity CG - 1 PDFJonna Marie Ibuna100% (1)

- Narrative ReportDokumen46 halamanNarrative ReportGINA F. GALOS100% (19)

- Persuasive Essay 2Dokumen5 halamanPersuasive Essay 2api-280215821100% (1)

- Job Description and Duties of A Computer TeacherDokumen2 halamanJob Description and Duties of A Computer TeacherBenjaminJrMoronia100% (1)

- CUS3701 Tutorial LetterDokumen52 halamanCUS3701 Tutorial LetterLuane Van Zyl LubbeBelum ada peringkat

- Social, Psychological & Philosophical Issues in EducationDokumen2 halamanSocial, Psychological & Philosophical Issues in EducationSonny Matias100% (4)