Microfinance

Diunggah oleh

Manas Ranjan MahantaJudul Asli

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Microfinance

Diunggah oleh

Manas Ranjan MahantaHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Project Report On Analysis of Microfinance Industry in India PROJECT WORK PAPER NO.

XXXVII (OPTION B) TERM PAPER SUBMITTED BY: Ashish Chopra College Roll No. 5221 B. Com (H) - III Year Academic Year: 2010-11 Hans Raj College University of Delhi The project has been submitted to the DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE and has been made u nder the guidance of MS. REETIKA JAIN 1 Certificate This is to certify that the project report titled Analysis of Microfinance Indust ry in India has been carried out by Ashish Chopra, Roll No. 5221, Batch 2010-11 f or the partial fulfilment of the Bachelor of Commerce (Honours). Ashish Chopra B. Com (H) III Year College Roll No. 5221 Hans Raj College Mr. Rakesh Aggarwal Teacher In charge Department of Commerce Hans Raj College Ms. Reetika Jain Mentor Department of Commerce Hans Raj College 2 Declaration I, Ashish Chopra, hereby declare that the project report titled Analysis of Micro finance Industry in India is my original piece of work and is based on my underst anding of the subject. It has not been copied from any published source or websi te. Ashish Chopra B. Com (H) III Year College Roll No. 5221 Hans Raj College 3 Acknowledgement As a student of commerce, I have gone through a vast amount of literature and ma terial available on the topic Microfinance. I feel indebted to several authors and researchers who helped me a lot in understanding various issues relating to my topic. I owe many thanks and gratitude to Ms. Reetika Jain, my mentor and guide for the project. The guidelines laid down by her have been very instrumental in the suc cessful completion of the project. I felt motivated and exceedingly encouraged u nder her supervision. She guided me to a wide range of resources that became a c atalyst in the project development. In addition, I sincerely thank my family and friends who provided me their suppo rt. Ashish Chopra B. Com (H) III Year College Roll No. 5221 Hans Raj College 4 Index

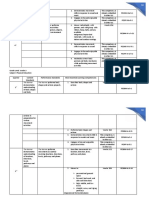

Certificate..................................................................... ............................................. 2 Declaration..................... ................................................................................ ........... 3 Acknowledgement................................................... .................................................. 4 Section 1: An overview of the Indian Microfinance Industry 1. Introduction to Microfinance 1.1. Microfinance Definitions................... ............................ 7 1.2. Functions of Microfinance Institutions...... .................... 7 1.3. Structures of Microfinance Institutions............. ............ 8 1.4. Who are clients of Micro-finance?........................... ...... 8 1.5. Inception of Microfinance......................................... ..... 9 1.6. Need in India...................................................... ............ 9 2. Models of Microfinance 2.1 Self Help Group (SHG) Bank Linkage Model.................. 11 2.2 Microfinance Institution (MFI) Model............. .............. 12 2.3 Legal Forms of MFI........................................ ................ 14 2.4 Regulation of Interest Rates............................ .............. 15 3. Principles of Microfinance................................. ........................................ 16 4. History of Microfinance in India 4.1 Focus on Financing the Poor......................................... 17 4.2 Rise of Self Help Groups................................................ 17 4.3 SHG Bank Linkage Model in India................................. 18 4.4 Summary of Strategic Policy Initiatives in India............ 20 5. Demand of Micro-credi t or Micro-finance in India.................................... 21 6. Scope of M icrofinance and its role in India 6.1 Microfinance: A game changer.............. ....................... 22 6.2 Role and Activities of Microfinance.............. ................ 23 7. Issues related to Microfinance in India 7.1 Problems face d by Borrowers...................................... 24 7.2 Problems faced by Le nders.......................................... 26 5 Section 2: Major Players particularly SKS Microfinance Ltd. CRISIL Ratings of Top MFIs...................................................... .. 29 Profile of Top 4 MFIs..................................................... ............ 31 o Asmitha Microfin Ltd.......................................... ........... 32 o Share Microfin Ltd............................................. ............ 33 o Spandana Sphoorthy Financial Ltd.............................. .. 34 o SKS Microfinance Ltd.................................................... . 35 The SKS Microfinance Ltd. Story............................................ ... 36 SKS Microfinance and its models of operation......................... 37 o Operations.................................................................... . 37 o Awards................................................................... ........ 38 o Models of Operation............................................... ....... 38 Conclusion........................................................... ................................................. 40 References................. ................................................................................ ........... 41 6 Section 1: An overview of the Indian Microfinance Industry Introduction Microfinance is the provision of financial services to low-income clients, inclu ding consumers and the self-employed, who traditionally lack access to banking a

nd related services. More broadly, it is a movement whose object is "a world in which as many poor and near-poor households as possible have permanent access to an appropriate range of high quality financial services, including not just cre dit but also savings, insurance, and fund transfers." Those who promote microfin ance generally believe that such access will help poor people out of poverty. Mi crofinance in India has had a significant shift from the days when microfinance was being discussed as the next big innovation to address the poverty issues in India to being discussed in terms of the next big investment opportunity. The la nguage of microfinance has undergone a fundamental change in the two decades of its evolution. Microfinance started with the recognition that poor people had th e capability to lift themselves out of poverty if they had access to affordable loans. High repayment rates in the industry have changed the perception that the poor are not credit worthy. With the right opportunities, the poor have proved themselves to be productive and capable of borrowing, saving and repaying, even without collateral. Bibi Hanifa is a successful micro entrepreneur from Hubli, Karnataka who has set up an incense-stick unit along with a group of women in her neighbourhood. Earl ier they worked as daily wage labor at a nearby factory and earned a meagre inco me. Today, thanks to the simple system of taking loans and repaying them, these women manage a successful enterprise and dream of a better and more prosperous t omorrow 7 Microfinance Definitions: According to International Labor Organization (ILO), Microfinance is an economic development approach that involves providing financial services through institut ions to low income clients. In India, Microfinance has been defined by The Nationa l Microfinance Taskforce, 1999 as provision of thrift, credit and other financial services and products of very small amounts to the poor in rural, semi-urban or urban areas for enabling them to raise their income levels and improve living st andards. "The poor stay poor, not because they are lazy but because they have no access to capital." The dictionary meaning of finance is management of money. The management of money denotes acquiring & using money. Micro Finance is buzzing wo rd, used when financing for micro entrepreneurs. Concept of micro finance is eme rged in need of meeting special goal to empower under-privileged class of societ y, women, and poor, downtrodden by natural reasons or men made; caste, creed, re ligion or otherwise. The principles of Micro Finance are founded on the philosop hy of cooperation and its central values of equality, equity and mutual self-hel p. At the heart of these principles are the concept of human development and the brotherhood of man expressed through people working together to achieve a bette r life for themselves and their children. Microcredit or Microfinance is the pro cess of granting small loans to poor people, primarily to women, who have no col lateral and are marginalised. These women tend to use their income to benefit th eir households and children. The process is accomplished through a microfinance institution. Functions of a Microfinance institution: recruits and trains responsible, appropriate borrowers, each of whom establishes her small business helps them form groups that are accountable for each others loans distributes funds for loans meets with groups of borrowers to collect loa n repayments and to guide their endeavours 8

Examples of enterprises established include, buying a buffalo to sell its milk; starting a kirana store; manufacturing sweets; selling soft drinks; grinding spi ces; sewing; candle making; collecting fallen hair for wigs and extensions; repa iring watches; tea or petty shops; vegetable stands; bicycle repair; carpentry a nd welding shop or an auto rickshaw. Structures of a Microfinance Institution Microfinance institutions broadly operate under a wide range of legal structures . They could be registered as1. NGO, 2. Trusts, 3. Sec 25 Companies, 4. Cooperat ive Societies, 5. Cooperative Banks, 6. Regional Rural Banks, 7. Local Area Bank s, 8. Public and Private Sector banks, 9. Business Correspondents and 10. Non-Ba nking Finance Companies. For instance, SKS Microfinance is registered with the R BI as a non-deposit taking NBFC and is regulated by the RBI. Who are the clients of micro finance? The typical micro finance clients are low-income persons that do not have access to formal financial institutions. Micro finance clients are typically self-empl oyed, often household-based entrepreneurs. In rural areas, they are usually smal l farmers and others who are engaged in small income-generating activities such as food processing and petty trade. In urban areas, micro finance activities are more diverse and include shopkeepers, service providers, artisans, street vendo rs, etc. Micro finance clients are poor and vulnerable non-poor who have a relat ively unstable source of income. India has 800 million poor people who live on t he brink of subsistence. This is one of the largest populations of poor in the w orld. The bottom 5% of Indias poor, considered ultra poor, face even deeper levels of chronic hunger, persistent poor health and illiteracy. 9 To cope with their vulnerability, the poor have no choice but to take loan for c onsumption and income generation from money lenders that charge exploitative rat es of interest. This can put the poor in a debt trap. If poor people can access loans with fair interest rates, they could break out of the cycle of poverty. Bu reaucracy, corruption, illiteracy and challenging logistics prevent the poor fro m accessing loans from banks and the government. Inception of Microfinance Microfinance in India started in 1974 in Gujarat as Shri Mahila SEWA (Self Emplo yed Womens Association) Sahakari Bank. Registered as an Urban Cooperative Bank, t hey provided banking services to poor women employed in the unorganised sector. Microfinance later evolved in the early 1980s around the concept of informal Sel fHelp Groups (SHGs) that provided deprived poor people with financial services. From modest origins, the microfinance sector has grown at a steady pace. Now in a strong endorsement of microfinance, the National Bank for Agriculture and Rura l Development (NABARD) and Small Industries Development Bank of India (SIDBI) ha ve committed themselves to developing microfinance. The microfinance sector has been "witnessing a tremendous growth" during the last few years in India in term s of loan portfolio, geographical area and outreach. With Indias GDP growing at t he rate of 7.1 % the countrys socio-economic pyramid is turning around the story with millions of poor people becoming entrepreneurs. The Need in India India is said to be the home of one third of the worlds poor; official estimates range from 26 to 50 percent of the more than one billion population. About 87 pe rcent of the poorest households do not have access to credit. The demand for mic rocredit has been estimated at up to $30 billion; the supply is less than $2.2 b illion combined by all involved in the sector. Due to the sheer size of the popu lation living in poverty, India is strategically significant in the global effor ts to alleviate poverty and to achieve the Millennium Development Goal of halvin g the worlds poverty by 2015. Microfinance has been present in India in one form

or another since the 1970s and is now widely accepted as an effective poverty al leviation strategy. Over the last five years, the microfinance industry has achi eved significant growth in part due to the participation of 10 commercial banks. Despite this growth, the poverty situation in India continues to be challenging. As we broaden the notion of the types of services micro finan ce encompasses, the potential market of micro finance clients also expands. It d epends on local conditions and political climate, activeness of cooperatives, SH G & NGOs and support mechanism. For instance, micro credit might have a far more limited market scope than say a more diversified range of financial services, w hich includes various types of savings products, payment and remittance services , and various insurance products. For example, many very poor farmers may not re ally wish to borrow, but rather, would like a safer place to save the proceeds f rom their harvest as these are consumed over several months by the requirements of daily living. Central government in India has established a strong & extensiv e link between NABARD (National Bank for Agriculture & Rural Development), State Cooperative Bank, District Cooperative Banks, Primary Agriculture & Marketing S ocieties at national, state, district and village level. 11 Models of Microfinance in India 1. Self Help Group (SHG) Bank Linkage Model: The microfinance movement started i n India with the introduction of the SHGBank Linkage Programme in the 1980s by N GOs that was later formalized by the Government of India in the early 1990s. Pur suant to the programme, banks, which are primarily public sector regional rural banks, are encouraged to partner with SHGs to provide them with funding support, which is often subsidized. A self help group, or SHG, is a group of 10 to 20 po or women in a village who come together to contribute regular savings to a commo n fund to deposit with a bank as collateral for future loans. The group has coll ective decision making power and obtains loans from the partner bank. The SHG th en loans these funds to its members at terms decided by the group. Members of th e group meet on a monthly basis to conduct transactions and group leaders are re sponsible for maintaining their own records, often with the help of NGOs or gove rnment agency staff. NABARD is presently operating three models of linkage of ba nks with SHGs and NGOs: Model 1: In this model, the bank itself acts as a Self H elp Group Promoting Institution (SHPI). It takes initiatives in forming the grou ps, nurtures them over a period of time and then provides credit to them after s atisfying itself about their maturity to absorb credit. About 16% of SHGs and 13 % of loan amounts are using this model (as of March 2002). Model 2: In this mode l, groups are formed by NGOs (in most of the cases) or by government agencies. T he groups are nurtured and trained by these agencies. The bank then provides cre dit directly to the SHGs, after observing their operations and maturity to absor b credit. While the bank provides loans to the groups directly, the facilitating agencies continue their interactions with the SHGs. Most linkage experiences be gin with this model with NGOs playing a major role. This model has also been pop ular and more acceptable to banks, as some of the difficult functions of social 12 dynamics are externalized. About 75% of SHGs and 78% of loan amounts are using t his model. Model 3: Due to various reasons, banks in some areas are not in a pos ition to even finance SHGs promoted and nurtured by other agencies. In such case s, the NGOs act as both facilitators and micro- finance intermediaries. First, t hey promote the groups, nurture and train them and then approach banks for bulk loans for on-lending to the SHGs. About 9% of SHGs and 13% of loan amounts are u

sing this model 2. Micro Finance Institution (MFI) Model: The MFI model has gained significant m omentum in India in recent years and continues to grow as the viable alternative to SHGs. In contrast to an SHG, an MFI is a separate legal organization that pr ovides financial services directly to borrowers. MFIs have their own employees, record keeping and accounting systems and are often subject to regulatory oversi ght. MFIs require borrowers from a village to organize themselves in small group s, typically of five women, that have joint decision making responsibility for t he approval of member loans. The groups meet weekly to conduct transactions. MFI staff travel to the villages to attend the weekly group meetings to disburse lo ans and collect repayments. Unlike SHGs, loans are issued by MFIs without collat eral or prior savings. MFIs now exist in a variety of legal forms, including tru sts, societies, cooperatives, non-profit NBFCs registered under Section 25 of th e Companies Act, 1956, or Section 25 Companies, and NBFCs registered with the RB I. Trusts, cooperatives and Section 25 companies are regulated by the specific a ct under which they are registered and not by the RBI. Attempts have been made b y some of the associations of MFIs like Sa-Dhan to capture the business volume o f the MFI sector. As per the Bharat Micro Finance Report of Sa-Dhan, in March 20 09, the 233 member MFIs of Sa-Dhan 13 had an outreach of 22.6 million clients with an outstanding microfinance portfol io of INR 117 billion (USD 2.5 billion). Legal Forms of MFIs in India * The estimated number includes only those MFIs, which are actually undertaking lending activity. Adapted from www.nabard.org 14 Regulation of Interest Rates The interest rates are deregulated not only for private MFIs but also for formal banking sector. In the context of softening of interest rates in the formal ban king sector, the comparatively higher interest rate (12 to 24 per cent per annum ) charged by the MFIs has become a contentious issue. The high interest rate col lected by the MFIs from their poor clients is perceived as exploitative. It is a rgued that raising interest rates too high could undermine the social and econom ic impact on poor clients. Since most MFIs have lower business volumes, their tr ansaction costs are far higher than that of the formal banking channels. The hig h cost structure of MFIs would affect their sustainability in the long run. Lend ing small amounts to the poor is expensive and is the reason so many rural poor have been excluded from the mainstream financial system for so long. In order to operate in hard to reach areas, provisioning such small loans, MFIs must charge higher interest rates, which currently average 28% to 33%, to cover their costs . While higher than mainstream banks loaning to richer customers, these rates ar e much lower than those levied by local moneylendersoften the rural poors only oth er option. 15 Principles of Microfinance Some principles that summarize a century and a half of development practice were encapsulated in 2004 by Consultative Group to Assist the Poor (CGAP): Poor peop

le need not just loans but also savings, insurance and money transfer services. Microfinance must be useful to poor households: helping them raise income, build up assets and/or cushion themselves against external shocks. Microfinance can pa y for itself. Subsidies from donors and government are scarce and uncertain, and so to reach large numbers of poor people, microfinance must pay for itself. Micr ofinance means building permanent local institutions. Microfinance also means in tegrating the financial needs of poor people into a countrys mainstream financial system. The job of government is to enable financial services, not to provide t hem. Donor funds should complement private capital, not compete with it. The key bot tleneck is the shortage of strong institutions and managers. Donors should focus on capacity building. Interest rate ceilings hurt poor people by preventing micr ofinance institutions from covering their costs, which chokes off the supply of credit. Microfinance institutions should measure and disclose their performance both financially and socially.

These principles were endorsed by the Group of Eight leaders at the G8 Summit on June 10, 2004. 16 A Brief History of Microfinance Microfinance has evolved over the past quarter century across India into various operating forms and to a varying degree of success. One such form of microfinan ce has been the development of the self-help movement. Based on the concept of se lfhelp, small groups of women have formed into groups of ten to twenty and operat e a savings-first business model whereby the members savings are used to fund loa ns. The results from these self-help groups (SHGs) are promising and have become a focus of intense examination as it is proving to be an effective method of po verty reduction. Focus on Financing the Poor The post-nationalization period in the banking sector, circa 1969, witnessed a s ubstantial amount of resources being earmarked towards meeting the credit needs of the poor. There were several objectives for the bank nationalization strategy including expanding the outreach of financial services to neglected sectors. As a result of this strategy, Credit came to be recognized as a remedy for many of the ills of the poverty. While the objectives were laudable and substantial pro gress was achieved, credit flow to the poor, and especially to poor women, remai ned low. This led to initiatives that were institution driven that attempted to converge the existing strengths of rural banking infrastructure and leverage thi s to better serve the poor. The pioneering efforts at this were made by National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development (NABARD), which was given the tasks of framing appropriate policy for rural credit, provision of technical assistanc e backed liquidity support to banks, supervision of rural credit institutions an d other development initiatives. Rise of Self Help Groups This lead to the rise of Self Help Groups and more formal SHG Federations couple d now with SHG Bank Linkage have made this a dominant form of microfinance in ad dition to microfinance institutions (MFI). The policy environment in India has b een extremely supportive for the growth of the microfinance sector in India. Par ticularly during the International Year of Microcredit 2005, significant policy announcements 17

from the Government of India (GoI) and the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) have serv ed as a shot in the arm for rapid growth. SHGs have spread rapidly due to their ease of replication. SHG Bank Linkage has provided the capacity for SHGs to incr ease their capital base to fund more members and bigger projects. Today, it is e stimated that there are at least over 2 million SHGs in India. In many Indian st ates, SHGs are networking themselves into federations to achieve institutional a nd financial sustainability. Cumulatively, 1.6 million SHGs have been bank-linke d with cumulative loans of Rs. 69 billion. In 2004-05 alone, almost 800,000 SHGs were bank-linked. While no definitive date has been determined for the actual c onception and propagation of SHGs, the practice of small groups of rural and urb an people banding together to form a savings and credit organization is well est ablished in India. In the early stages, NGOs played a pivotal role in innovating the SHG model and in implementing the model to develop the process fully. In th e 1980s, policy makers took notice and worked with development organizations and bankers to discuss the possibility of promoting these savings and credit groups . Their efforts and the simplicity of SHGs helped to spread the movement across the country. State governments established revolving loan funds which were used to fund SHGs. By the 1990s, SHGs were viewed by state governments and NGOs to be more than just a financial intermediation but as a common interest group, worki ng on other concerns as well. The agenda of SHGs included social and political i ssues as well. The spread of SHGs led also to the formation of SHG Federations w hich are a more sophisticated form of organization that involve several SHGs for ming into Village Organizations (VO) / Cluster Federations and then ultimately i nto higher level federations (called as Mandal Samakhya (MS) in AP or SHG Federa tion generally). SHG Federations are formal institutions while the SHGs are info rmal. Many of these SHG federations are registered as societies, mutual benefit trusts and mutually aided cooperative societies. SHG Bank Linkage Model in India A most notable milestone in the SHG movement was when NABARD launched the pilot phase of the SHG Bank Linkage programme in February 1992. This was the first ins tance of mature SHGs that were directly financed by a commercial bank. The infor mal thrift and credit groups of poor were recognised as bankable clients. Soon a fter, the RBI advised commercial banks to consider lending to SHGs as part of th eir rural credit operations thus creating SHG Bank Linkage. The linking of SHGs with the 18 financial sector was good for both sides. The banks were able to tap into a larg e market, namely the low-income households, transactions costs were low and repa yment rates were high. The SHGs were able to scale up their operations with more financing and they had access to more credit products. The institutionalisation of self help groups (SHGs) and their recognition by the banking system as a sav ing and effective credit delivery mechanism in 1990s was an important step in fi nancial inclusion of the relatively less banked or unbanked rural areas. More so , because it was built on a premise that the SHG mechanism would instil credit d iscipline in the members and one day empower them to become individual clients o f banks. What followed was a proliferation of the SHG-Bank Linkage Programme (SH G-BLP) to unprecedented heights (albeit not equitable). After the pilot testing phase from 1992 to 1995, the Reserve Bank of India advised banks that lending to SHGs should be treated as a normal banking activity in 1996. This led to the se cond phase (mainstreaming) of the programme as banks started financing SHGs on a relatively larger scale. During 1998-99, there was a quantum jump in the number of SHGs that had availed of loans from the banking system to 18,678 from 5,719 during 1997-98.This was the beginning of the growth and expansion phase (see gra phic). As on March 31, 2009 42.24 lakh SHGs had loans outstanding with the banki ng system, which included 9.77 lakh SHGs under Swaranjayanti Gram Swarozgar Yoja

na (SGSY). The loan outstanding to the banking system, of non SGSY SHGs, was Rs 16,818 crore. 19 Summary of Strategic Policy Initiatives in India Some of the most noteworthy strategic policy initiatives in the area of Microfin ance taken by the government and regulatory bodies in India are: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Working group on credit to the poor through SHGs, NGOs, NABARD, 1995 The Nationa l Microfinance Taskforce, 1999 Working Group on Financial Flows to the Informal Sector (set up by PMO), 2002 Microfinance Development and Equity Fund, NABARD, 2 005 Working group on Financing NBFCs by Banks- RBI 20 Demand for Micro-credit or Microfinance In terms of demand for micro-credit or micro-finance, there are three segments, which demand funds. They are: 1. At the very bottom in terms of income and asset s , are those who are landless and engaged in agricultural activities on a seaso nal basis, and manual labourers in forestry, mining, household industries and co nstruction. This segment requires, first and foremost, consumption credit during those months when they do not get labour work, and for contingencies such as il lness. They also need credit for acquiring small productive assets, such as live stock, using which they can generate additional income. The next market segment is small and marginal farmers and rural artisans, weavers and those self-employe d in the urban informal sector as hawkers, vendors, and workers in household mic ro-enterprises. This segment mainly needs credit for working capital, a small pa rt of which also serves consumption needs. This segment also needs term credit f or acquiring additional productive assets, such as irrigation pumpsets, borewell s and livestock in case of farmers, and equipment (looms, machinery) and workshe ds in case of non-farm workers. The third market segment is of small and medium farmers who have gone in for commercial crops such as surplus paddy and wheat, c otton, groundnut, and others engaged in dairying, poultry, fishery, etc. Among n on-farm activities, this segment includes those in villages and slums, engaged i n processing or manufacturing activity, running provision stores, repair worksho ps, tea shops, and various service enterprises. These persons are not always poo r, though they live barely above the poverty line and also suffer from inadequat e access to formal credit. 2. 3. 21 Scope of Microfinance and its Role in India Microfinance Institutions (MFIs) are uniquely positioned to facilitate financial inclusion, and provide financial services to a clientele poorer and more vulner able than the traditional bank clientele. There is no comprehensive regulatory f ramework for the microfinance sector in India: MFIs exist in many legal forms. M any mid-sized and large MFIs are, however, acquiring and floating new companies to get registered as non-banking financial institutions (NBFCs), which will help them achieve scale. Microfinance: A game changer Microfinance began in India in the 1990s as a way of alleviating poverty, by enc ouraging income generating activities by poor households. Since then, the outrea

ch of microfinance institutions (MFIs) in India has crossed 30 million poor hous eholds as at the end of March 2010. This is very commendable. However, there are two issues need to be addressed how to reduce interest rates and the net impact of microcredit. Let me take the example of BASIX (headquartered in Hyderabad, A ndhra Pradesh), which is working with over a million poor households. For the fi rst five years since inception in 1996, BASIX took the approach of primarily del ivering micro-credit to its customers. After five years of pursuing this approac h, BASIX carried out an impact assessment the year 2001. The results of this wer e rather disappointing. Only 52% of the customers, who had received at least thr ee rounds of micro-credit from BASIX, showed a significant increase in their inc ome (compared to a control group), 25% reported no change in income levels and 2 3% reported decline in their income levels. BASIX then carried out a detailed st udy of those who had had no increase or even a decline in income and found that the reasons for this could be clubbed into three factors: (1) Un-managed risk in their lives and livelihoods (2) Low productivity, in terms of poor yields and h igher costs, and (3) Unfavourable terms in input and output market transactions. This showed that there is a need for risk mitigation, yield enhancement, cost r eduction, and bringing rural producers together for better bargaining at the mar ket place. Hence in 2002, BASIX revised its strategy, to provide a comprehensive set of 22 livelihood promotion services to rural poor households. BASIX reaffirmed that cr edit is a necessary but not sufficient condition for livelihood promotion. Its r evised Livelihood Triad Strategy included provision of financial services beyond c redit such as insurance; provision of agricultural, livestock and non-farm enter prise development services; and institutional development services for producer organisations. Role and Activities of Microfinance: Microcredit: It is a small amount of money loaned to a client by a bank or other institution. Microcredit can be offered, often without collateral, to an indivi dual or through group lending. Micro savings: These are deposit services that al low one to save small amounts of money for future use. Often without minimum bal ance requirements, these savings accounts allow households to save in order to m eet unexpected expenses and plan for future expenses. Micro insurance: It is a s ystem by which people, businesses and other organizations make a payment to shar e risk. Access to insurance enables entrepreneurs to concentrate more on develop ing their businesses while mitigating other risks affecting property, health or the ability to work. Remittances: These are transfer of funds from people in one place to people in another, usually across borders to family and friends. Compa red with other sources of capital that can fluctuate depending on the political or economic climate, remittances are a relatively steady source of funds

23 Issues related to Microfinance in India Problems faced by Borrowers 1. Coercion One of the most important moral issues being raised in relation to m icrofinance is that of coercion. After 54 people killed themselves in the state of Andhra Pradesh in October 2010, Indian authorities placed microfinance instit utions (MFI) under a microscope, and drafted new rules the MFI companies must fo llow. The farmers were reportedly deep in debt to microfinance institutions (MFI

s). "Microfinance institutions charge exorbitant interest rates. The poor are dr iven to take their own lives because of their burden of debt and the brutal meth ods used to call in the loans", the chief minister of Andhra Pradesh said. 2. Brutal and Aggressive Debt-Collection Tactics "The people calling in the loan s are often not aware of the code of conduct of the MFIs. Many of the MFIs have b een resort to brutal methods for collection of debt from these borrowers. News i tems like the one below are quite common in India. Unable to repay Rs. 235, Farm er kills self MFI Loan Suicide, Hyderabad News A farmer committed suicide by con suming pesticides, allegedly after being harassed by the collection agents of a microfinance institution at in Nalgonda district, Andhra Pradesh. 3. Joint Micro finance Joint microloans are granted to a group of people who are jointly respon sible for repaying the loan. Individual failures to pay (due to illness or a bad week) are avoided and group pressure serves as a strong incentive in ensuring res ponsible behavior by making loans to individuals within a lending circle. The in dividuals meet regularly, ostensibly creating a self-help group. In reality, all the borrowers in the group are responsible for making the loan repayment if a m ember defaults, so peer pressure is a very strong factor." 24 However, in case of default either due to business failures, unproductive expend iture or greed to consume more, all members are troubled. 4. High Interest Rates Many in the urban centres would commit suicide if the banks start charging us 2 4 per cent rate of interest. Even at 8.5 per cent rate of interest, those who ha ve drawn housing loans, find it difficult to make monthly EMI payments. Imagine the stress and threat under which the poor in the rural areas are being made to borrow at 24 per cent rate of interest. Whatever the justification for charging 24 per cent rate of interest, how can human beings exploit a hungry stomach in t he name of a successful business model? 5. Not aimed at lifting people out of po verty Micro finance serves not to lift people out of poverty but, assist those n ear or slightly above the poverty line. Money is given to those people who have a possibility of returning the principle amount. This leads to the fact that len ding money to these people is feasible and sustainable, while lending to the poo rest of the poor is not. 6. Poverty alleviation mission has now been reduced to a Money making tactic of MNCs Micro finance has now, become a weapon for multina tional companies to sell their products, by collaborating with such institutions . This in turn, is destroying the spirit of micro credit. For instance: Recently a mobile phone manufacturer offered a micro financing scheme on a pilot basis i n Andhra Pradesh and Karnataka, to sell their handset to the poorest. Under this project, the company was offering an easy payment scheme of Rs 100 per week ove r a period of time. Andhra Pradesh has promulgated an ordinance to check malprac tices in microfinance institutions (MFIs). The state should not throw out the ba by with the bathwater: it should check malpractices without checking MFI growth. Globally, MFIs have expanded at phenomenal rates largely because they lend with out loan scrutiny to groups of women, and peer pressure of the group keeps defau lts below 2% despite the absence of any collateral or legal procedures for loan 25 recovery. MFIs are, in effect, benevolent moneylenders, charging interest rates of around 30% to cover high operational costs. They are a great improvement on m oneylenders charging 60% and using force to seize assets. However, the AP media accuse some MFIs of using force too, and claim that some suicides have been caus ed by such coercion. Proving the connection is difficult: Persons commit suicide for several reasons, ranging from psychological to financial issues. The global suicide rate is 14 per lakh persons, it is even higher in rich countries like F inland and Japan which have no MFIs. No rules or regulations can end suicides. B ut rules should certainly be framed to stop forcible loan recovery. The top MFIs agree on the need to ensure there is no coercion, and have adopted a code of co

nduct on this. But while bad apples among MFIs must be dealt with firmly, care m ust be taken not to create new regulations that encourage corruption or crimp le gitimate and desirable MFI lending. Proposals to prevent members of self-help gr oups from borrowing from MFIs are terribly wrong, and will penalise poor borrowe rs and hit financial inclusion. People should be free to borrow from all sources , and members of self help groups should not require a no-objection certificate before applying for an MFI loan it will be one more avenue for corruption and ha rassment. The use of force is an issue that must not be mixed up with the separa te question of how the RBI should regulate MFIs. MFIs have reached 20 million pe ople in a few years, a success owing something to light regulation that facilita ted much innovation and experimentation. Some MFIs have become large institution s, and large ones need tougher regulation. But care should be taken to give MFIs , especially smaller ones, continued scope for innovation and experimentation. Problems faced by Lenders 1. Sustainability The first challenge relates to sustainability. MFI model is co mparatively costlier in terms of delivery of financial services. An analysis of 36 leading MFIs by Jindal & Sharma shows that 89% MFIs sample were subsidy depen dent and only 9 were able to cover more than 80% of their costs. This is partly explained by the fact that while the cost of supervision of credit is high, the loan volumes and 26 loan size is low. It has also been commented that MFIs pass on the higher cost o f credit to their clients who are interest insensitive for small loans but may not be so as loan sizes increase. It is, therefore, necessary for MFIs to develop s trategies for increasing the range and volume of their financial services. 2. La ck of Capital The second area of concern for MFIs, which are on the growth path, is that they face a paucity of owned funds. This is a critical constraint in th eir being able to scale up. Many of the MFIs are socially oriented institutions and do not have adequate access to financial capital. As a result they have high debt equity ratios. Presently, there is no reliable mechanism in the country fo r meeting the equity requirements of MFIs. The IPO issue by Mexico based Comparta mos was not accepted by purists as they thought it defied the mission of an MFI. The IPO also brought forth the issue of valuation of an MFI 3. Financial service delivery Another challenge faced by MFIs is the inability to access supply chai n. This challenge can be overcome by exploring synergies between microfinance in stitutions with expertise in credit delivery and community mobilization and busi nesses operating with production supply chains such as agriculture. The latter p layers who bring with them an understanding of similar client segments, ability to create microenterprise opportunities and willingness to nurture them, would b e keen on directing microfinance to such opportunities. This enables MFIs to inc rease their client base at no additional costs. Those businesses that procure fr om rural India such as agriculture and dairy often identify finance as a constra int to value creation. Such businesses may find complementarities between an MFIs skills in management of credit processes and their own strengths in supply chai n management. ITC Limited, with its strong supply chain logistics, rural presenc e and an innovative transaction platform, the e-choupal, has started exploring s ynergies with financial service providers including MFIs through pilots with veg etable vendors and farmers. Similarly, large FIs such as Spandana foresee a larg er role for themselves in the rural economy ably supported by value creating par tnerships with players such as Mahindra and Western Union Money Transfer. 27 ITC has initiated a pilot project called pushcarts scheme along with BASIX (a micr ofinance organization in Hyderabad). Under this pilot, it works with twenty wome n head load vendors selling vegetables of around 10- 15 kgs per day. BASIX exten ds working capital loans of Rs. 10,000/- , capacity building and business develo

pment support to the women. ITC provides support through supply chain innovation s by: 1. Making the Choupal Fresh stores available to the vendors, this avoids t he hassle of bargaining and unreliability at the traditional mandis (local veget able markets). 2. Continuously experimenting to increase efficiency, augmenting incomes and reducing energy usage across the value chain. For instance, it has f orged a partnership with National Institute of Design (NID), a pioneer in the fi eld of design education and research, to design user-friendly pushcarts that can reduce the physical burden. 3. Taking lessons from the pharmaceutical and telec om sector to identify technologies that can save energy and ensure temperature c ontrol in push carts in order to maintain quality of the vegetables throughout t he day. The model augments the incomes of the vendors from around Rs.30-40 per d ay to an average of Rs.150 per day. From an environmental point of view, push ca rts are much more energy efficient as opposed to fixed format retail outlets 28 Section 2: Major Players particularly SKS Finance In late 2009, CRISIL which is Indias leading ratings, research and risk advisory company released its list of top 50 microfinance institutions in India. The repo rt titled Indias Top 50 Microfinance Institutions presents an overview of leading players in Indias microfinance institution (MFI) space. This is the first inaugu ral issue and includes additional commentary analysing the key strengths and cha llenges of different microfinance players in the sector. The publication is part of CRISILs enabling role in the structured evolution of the MFI sector in India. CRISIL launched MFI grading as early as in 2002 and has since then become the w orlds first mainstream rating agency to develop a separate methodology and scale to assess MFIs. Currently CRISIL has assessed more than 140 MFIs, and is current ly the most preferred rating agency in the Indian microfinance space. In light o f SKS Microfinances proposed IPO in the coming days the CRISIL report is presente d below for the benefit of the readers of this blog. Market sources reveal that some of these microfinance institutions which figure in the top 50 are in talks with merchant bankers and investors to tap the primary markets and want to gauge the response to SKS Microfinances IPO before they fast track their own listing p lans. The four MFIs chosen for the research based on the CRISIL data are: 1. SKS Microfinance [SKS] 2. Spandana Spoorthy Financials Limited [Spandana], 3. Share Microfin Limited [SML] 4. Asmitha Microfin Limited [AML] 29 Based on the CRISIL data, each of these four institutions serve more than 8,00,0 00 customers, have a loan portfolio of more than US$ 100 million and an asset si ze of more than US$ 170 million each by the year end 2009. Of the four instituti ons listed above, three [except Asmitha] have followed a similar path in terms o f the original organizational structure, incorporation into a commercial format and the methodology of moving from a charitable construct to the commercial constru ct. Unlike the international counterparts of BancoSol and BC the legal framework in India did not permit the NGOs to take an equity position in for-profit financ e companies. The promoters of each of these institutions possibly did not have t he resources to meet the initial capitalization requirements of Rs. 2 Crore to s et up a for-profit finance company at that time. While this is not explicit, the nature of initial capitalization and the later movement gives enough reason to believe that personal resources were indeed a problem. Given the legal framework of non-profit societies which were operating in the microfinance space, it was impossible to shift the portfolio without the new company providing consideratio n in cash.

30 This posed a significant challenge because residual claims on current income and on liquidation cannot be applied for such purposes; the promoters had to look a t innovative mechanisms of utilizing the investments made in the non-profits in a meaningful manner. If we were to look at a legal mechanism to overcome this th ere could have been only two options: 1. Ensure that the residual claims are so low, by skimming resources above the line. This could be done by paying an exorb itant salary to the promoter and enrich him or her to generate personal wealth i n a legal manner to invest in the next wave of the business. It appears that thi s was not a route that these promoters preferred at that time, because all of th e promoters genuinely came from a developmental background. 2. The second option for these entities was to look at ways of distributing the un- distributable th e residual claims themselves the excess of income over expenditure as well as th e grant funds held in the books of the not-forprofits. When we look at each of t he four firms listed above, at least three of them resorted to the second option of using the grant funding sought in the not-for-profit organization to capital ize the for-profit operations of NBFCs. This possibly was done with a fairly ben ign intention at that time as it was seen as genuinely involving the community m embers who were also borrowers in the capital structure of the companies that we re being promoted. In fact this was honourably called transformation and all the se MFIs had no problems in sharing the details of the process with the world at large. The profiles of these Four Biggest Microfinance Institutions in India have been discussed in the following pages. 31 Position 4: Asmitha Microfin Ltd. 32 Position 3: Share Microfin Ltd. 33 Position 2: Spandana Sphoorthy Financial Ltd. 34 Position 1: SKS Microfinance Ltd. 35 The SKS MICROFINANCE LTD. Story

It was merely a coincidence that the year after C K Prahalads bestseller, The For tune at the Bottom of the Pyramid: Eradicating Poverty through Profits (2004), t hat Vikram Akula returned to SKS Microfinance, leaving a consultancy job at McKi nsey & Company in Chicago that he took a year earlier. Akula, a Fulbright Schola r researching poverty and a student of arts, had founded SKS Microfinance as a n on-profit venture in late 1997 with funding close to $52,000 raised from 357 peo ple. He converted it into a for-profit company in 2005 during his second stint. Success came rather swiftly. In 2006, Akula was named by Time magazine as one of the worlds 100 most influential people. In less than a decade, SKS emerged as th e largest micro-finance institution (MFI) in the country. Profits after tax (PAT ) increased from Rs 2 crore in FY07 to Rs 80 crore in FY09, and Rs 174 crore in FY10. Little wonder, then, that the companys recent initial public offering (IPO) attracted high-profile investors like billionaire George Soros, and was oversub scribed 13.69 times, even with the price fixed at the highest band of Rs 985 a s hare. After SKS success, more microfinance public issues are on the horizon The countrys second-largest MFI, Spandana Sphoorty Financial, which will decide o n whether to go for an IPO in the next month, is not far behind SKS. In fact, as an NGO, both SKS and Spandana started in 1998 in Andhra Pradesh. As on July 31, Spandana had loan outstandings of Rs 4,205 crore, against SKSs Rs 4,321 crore as in March. Moreover, Spandana is the most profitable MFI at Rs 203 crore the las t financial year. Along the lines of SKS, Spandana was started by NGO worker Pad maja Reddy at Chilakalurpet in Guntur District of Andhra Pradesh. She was workin g on local development projects funded predominantly by grants, when a woman rag -picker inspired her to strike out on her own. In the first two years (1998-2000 ), Spandana crossed the Rs 1-crore disbursement mark with around 2,000 clients. 36 SKS Microfinance and its Models of Operation SKS Microfinance was started in 1998 as non-profit SKS Society. It was funded by individual and institutional donations and focused on markets within its home s tate of Andhra Pradesh. In 2005 SKS decided to pursue an aggressive growth plan and transformed into a Non-Banking Financial Company (NBFC) named SKS Microfinan ce and regulated by the Reserve Bank of India (RBI). Since transformation, SKS h as been successful in creating a for-profit model of microfinance using commerci al funds that is scalable. Delivering services at the doorsteps of its members a nd following clearcut processes, SKS has been able to ensure a repayment rate of over 99 % on its loans. SKS Microfinance is Indias largest and one of the worlds fastest-growing microfinance organizations. Its mission is to empower the poor b y providing them collateral-free loans for income generation. SKS Microfinance h as 5.8 million clients (2010) in 1,627 branches in 19 states across India and to tal assets worth $897.9 million (Sept.09.) SKS charges an annual effective inte rest rate ranging from 26.7% to 31.4% Operations Its borrowers include agricultural laborers, mom-and-pop entrepreneurs, street v endors, home based artisans, and small scale producers, each living on less than $2 a day. It works on a model that would allow micro-finance institutions to sc ale up quickly so that they would never have to turn poor person away. Borrowers (mostly women) take loans for a range of income-generating activities, includin g livestock, agriculture, trade (such as vegetable vending), production (from ba sket weaving to pottery) and new age business (photography to beauty parlours). SKS also provides members with interest-free loans for emergencies as well as li fe insurance and loan cover insurance to borrowers. It leverages its equity to r aise debt from public sector, private sector and multinational banks operating i n India. This capital has helped the organisation scale up operations and reach

out to millions of poor households across the length and breadth of India. In ad dition to rapid expansion, SKS leads the industry in technology innovation and t ransparency. It is one of the first MFIs in the world to have a fully automated MIS 37 that streamlines operations and helps reduce transaction costs. It is setting up an ERP system that will ensure quick data transfers, data mining, data recovery facilities which will improve operational efficiencies and response times. Awards SKS was ranked as the Number 1 MFI in India and number 2 in the world by MIX Mar ket. Business Week has rated SKS as one of the most influential companies. SKS h as received numerous awards including the CGAP Pro-Poor Innovation Award, the AB N-Ambro/ Planet Finance Process Excellence Award, Citibank Information Integrity Award, the Digital Partners SEL Award, SHG Foundation funding and the Grameen F oundation USA Excellence Award. SKS is the only MFI in India to receive the MIX Transparency Certification. Models Its model is based on 3 principles1. Adopt a profit-oriented approach in order t o access commercial capitalStarting with the pitch that there is a high entrepre neurial spirit amongst the poor to raise the funds, SKS converted itself to forprofit status as soon as it got break even and got philanthropist Ravi Reddy to be a founding investor. Then it secured money from parties such as Unitus, a Sea ttle based NGO that helps promote micro-finance; SIDBI; and technology entrepren eur Vinod Khosla. Later, it was able to attract multimillion dollar lines of cre dit from Citibank, ABN Amro, and others. 2. Standardize products, training, and other processes in order to boost capacity- They collect standard repayments in round numbers of 25 or 30 rupees. Internally, they have factory style training m odels. They enroll about 500 loan officers every month. They participate in theo ry classes on Saturdays and practice what they have learned in the field during the week. They have shortened the training time for a loan officer to 2 months t hough the average time taken by other industry players is 4-6 months. 3. Use Tec hnology to reduce costs and limit errors- It could not find the software that su ited its requirements, so it they built their own simple and user friendly appli cations that a computer-illiterate loan officer with a 12th grade education can easily understand. The system is also internet enabled. 38 Given that electricity is unreliable in many areas they have installed car batte ries or gas powered generators as back-ups in many areas. Scaling up Customer Loyalty Instead of asking illiterate villagers to describe their seasonal pattern of cas h flows, they encourage them to use colored chalk powder and flowers to map out the village on the ground and tell where the poorest people lived, what kind of financial products they needed, which areas were lorded over by which loan shark s, etc. They set peoples tiny weekly repayments as low as $1 per week and health and whole life insurance premiums to be $10 a year and 25 cents per week respect ively. They also offer interest free emergency loans. The salaries of loan offic ers are not tied to repayment rates and they journey on mopeds to borrowers villa ges and schedule loan meetings as early as 7.00 A.M. Deep customer loyalty ultim ately results in a repayment rate of 99.5%. Leveraging the SKS brand Its payoff comes from high volumes. They are growing at 200% annually, adding 50

branches and 1,60,000 new customers a month. They are also using their deep dis tribution channels for selling soap, clothes, consumer electronics and other pac kaged goods. 39 Conclusion Microfinance refers to a movement that envisions a world in which many poor and n ear-poor households, have permanent access to an appropriate range of high quali ty financial services, including not just credit but also savings, insurance and fund transfers. The microfinance sector in India has developed a successful and sustainable business model which has been able to overcome challenges traditiona lly faced by the financial services sector in servicing the low income populatio n by catering to its specific needs, capacities and leveraging pre-existing comm unity support networks. The concept has grown over the past two decades. Over th e years, major commercial banks and multinational corporations have decided to s ponsor it. However, this type of financing has a darker side too. Most of studie s are qualitative which tell that more than 90 per cent of the people who receiv e micro credit are poor and most of them succeed in businesses started with thes e loans. But the suicides committed by Indian farmers after being harassed by th e microfinance institutions (MFIs) for their inability to repay the debt have ra ised serious moral and ethical issues against the institutions. The aggressive d ebt-collection tactics of these MFIs have left us wondering if the government ha s been playing ignorant to the modus operandi of MFIs. Moreover, the interest ra tes charged by micro financing institutions are usurious. Today, MFIs pay little attention to the core concerns of the poor. For them the critical concern is to sustain services against emerging odds. Weve seen a major mission drift in micro finance, from being a social agency first, to being primarily a lending agency that wants to maximise its profit. Thus, there is a great need to set out rules limiting interest rates and stipulating legal consequences for the MFIs who badg er/ harass borrowers for payments. 40 References Online 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. Sksindia.com http://www.editor ialjunction.com/opinions/mfis-yes-coercion-no/ http://business-standard.com/indi a/news/after-sks-success-moremicrofinance-public-issues-arethe-horizon/406417/ h ttp://www.nabard.org/microfinance/mf_institution.asp http://www.microfinanceinsi ghts.com/blog-details.php?bid=223 http://www.scribd.com/doc/1194640/Micro-Financ e CRISIL ratings India- top 50 MFIs The Financial Express- Microfinance World: A pr-June 2010 http://www.portalmicrofinanzas.org/p/site/s/template.rc/1.1.8214/?p age 1=print http://www.digitaljournal.com/article/299621 http://indiamicrofinanc e.com/micro-finance-also-leads-to-suicides-inrural-areas.html http://mifin.wordp ress.com/ http://www.rnw.nl/english/article/stricter-rules-microfinance-after-in diasuicides Newspapers 1. 2. 3. 4. Times of India Business Standard Economic Times The Hindu 41

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (345)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (121)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- Power Curbers, Inc. v. E. D. Etnyre & Co. and A. E. Finley & Associates, Inc., 298 F.2d 484, 4th Cir. (1962)Dokumen18 halamanPower Curbers, Inc. v. E. D. Etnyre & Co. and A. E. Finley & Associates, Inc., 298 F.2d 484, 4th Cir. (1962)Scribd Government DocsBelum ada peringkat

- Iaea Tecdoc 1092Dokumen287 halamanIaea Tecdoc 1092Andres AracenaBelum ada peringkat

- Phylogeny Practice ProblemsDokumen3 halamanPhylogeny Practice ProblemsSusan Johnson100% (1)

- Ritesh Agarwal: Presented By: Bhavik Patel (Iu1981810008) ABHISHEK SHARMA (IU1981810001) VISHAL RATHI (IU1981810064)Dokumen19 halamanRitesh Agarwal: Presented By: Bhavik Patel (Iu1981810008) ABHISHEK SHARMA (IU1981810001) VISHAL RATHI (IU1981810064)Abhi SharmaBelum ada peringkat

- Soil NailingDokumen6 halamanSoil Nailingvinodreddy146Belum ada peringkat

- Chemistry Investigatory Project (R)Dokumen23 halamanChemistry Investigatory Project (R)BhagyashreeBelum ada peringkat

- Pulmonary EmbolismDokumen48 halamanPulmonary Embolismganga2424100% (3)

- Airport & Harbour Engg-AssignmentDokumen3 halamanAirport & Harbour Engg-AssignmentAshok Kumar RajanavarBelum ada peringkat

- PE MELCs Grade 3Dokumen4 halamanPE MELCs Grade 3MARISSA BERNALDOBelum ada peringkat

- Report FinalDokumen48 halamanReport FinalSantosh ChaudharyBelum ada peringkat

- Poetry UnitDokumen212 halamanPoetry Unittrovatore48100% (2)

- Roxas City For Revision Research 7 Q1 MELC 23 Week2Dokumen10 halamanRoxas City For Revision Research 7 Q1 MELC 23 Week2Rachele DolleteBelum ada peringkat

- Google Tools: Reggie Luther Tracsoft, Inc. 706-568-4133Dokumen23 halamanGoogle Tools: Reggie Luther Tracsoft, Inc. 706-568-4133nbaghrechaBelum ada peringkat

- Aliping PDFDokumen54 halamanAliping PDFDirect LukeBelum ada peringkat

- Csu Cep Professional Dispositions 1Dokumen6 halamanCsu Cep Professional Dispositions 1api-502440235Belum ada peringkat

- Virtual Assets Act, 2022Dokumen18 halamanVirtual Assets Act, 2022Rapulu UdohBelum ada peringkat

- Ring and Johnson CounterDokumen5 halamanRing and Johnson CounterkrsekarBelum ada peringkat

- HepaDokumen1 halamanHepasenthilarasu5100% (1)

- Project Management TY BSC ITDokumen57 halamanProject Management TY BSC ITdarshan130275% (12)

- Mathematics Mock Exam 2015Dokumen4 halamanMathematics Mock Exam 2015Ian BautistaBelum ada peringkat

- Production of Bioethanol From Empty Fruit Bunch (Efb) of Oil PalmDokumen26 halamanProduction of Bioethanol From Empty Fruit Bunch (Efb) of Oil PalmcelestavionaBelum ada peringkat

- Experiment - 1: Batch (Differential) Distillation: 1. ObjectiveDokumen30 halamanExperiment - 1: Batch (Differential) Distillation: 1. ObjectiveNaren ParasharBelum ada peringkat

- (Campus of Open Learning) University of Delhi Delhi-110007Dokumen1 halaman(Campus of Open Learning) University of Delhi Delhi-110007Sahil Singh RanaBelum ada peringkat

- Siemens Rapidlab 248, 348, 840, 845, 850, 855, 860, 865: Reagents & ControlsDokumen2 halamanSiemens Rapidlab 248, 348, 840, 845, 850, 855, 860, 865: Reagents & ControlsJuan Carlos CrespoBelum ada peringkat

- Lesson Plan For Implementing NETSDokumen5 halamanLesson Plan For Implementing NETSLisa PizzutoBelum ada peringkat

- Toh MFS8B 98B 003-11114-3AG1 PDFDokumen92 halamanToh MFS8B 98B 003-11114-3AG1 PDFDmitry NemtsoffBelum ada peringkat

- Smart Protein Plant Based Food Sector Report 2Dokumen199 halamanSmart Protein Plant Based Food Sector Report 2campeon00magnatesBelum ada peringkat

- Notes On Antibodies PropertiesDokumen3 halamanNotes On Antibodies PropertiesBidur Acharya100% (1)

- Data StructuresDokumen4 halamanData StructuresBenjB1983Belum ada peringkat

- NABARD R&D Seminar FormatDokumen7 halamanNABARD R&D Seminar FormatAnupam G. RatheeBelum ada peringkat