Corporate Ethics Statements - Murphy.1007 - BF00872326

Diunggah oleh

Carlos MonakosDeskripsi Asli:

Judul Asli

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Corporate Ethics Statements - Murphy.1007 - BF00872326

Diunggah oleh

Carlos MonakosHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Corporate Ethics Statements" Current Status and Future Prospects

Patrick E. Murphy

ABSTRACT. This paper reports on a stud,/ of large U.S. based corporations concerning the status of formal ethics statements. Almost all responding firms (9t%) have promulgated a formal code of ethics while one-half have published values statements and about one-third have a corporate credo. Analysis of these statements concentrated on to whom they are communicated; whether codes of ethics contain information pertinent to the industry, include sanctions for violations and provide specific guidance regarding gifts. Conclusions and implications for managers and researchers are drawn.

The late 1980s and early 1990s have seen much discussion of corporate ethical policies. Ma W companies have issued or revised public statements regarding their firm's ethical posture. These documents generally fall into three categories: corporate credos, codes of ethics and values statements. CEOs and other top corporate executives sometimes publicly proclaim their company's commitment to ethics by making reference to them. Some proclamations are surely for public relations purposes, but more serious attention now seems to be devoted to ethical decision making throughout major U.S. corporations. This emphasis on ethics is not new, however, among a few of the best known American firms. Patrick E. Murphy is Professor and Chairman of the Department of Marketing at the University of Notre Dame. He is coauthor ('with G. R. Laczniak) of Ethical Marketing Decisions: The Higher Road, Altyn & Bacon, 1993. His research interestsfocus on ethical and public policy issues facing marketing and business. He serves on the editorial review boards of several marketing and ethicsjournals.

For instance, the J.C. Penney Company promuigated a basic code of conduct, more appropriately labeled a credo, in I913. The Penney Idea consists of seven statements that reflected the founder's corporate philosophy (Oliverio, 1989). Although somewhat dated in its phrasing, the last point relates directly to ethics: "To test our every policy, method and act in this wise: Does it square with what is right and just?" Another noteworthy company, Johnson & Johnson, inaugurated its corporate ethics statement in the 1940s. Many firms responded to the growing criticism of their international operations and other domestic problems in the t970s by instituting formal ethics codes and policies. For example, Caterpillar introduced its well known code in t974. Since that time, other corporations have invested a substantial amount o f energy in revising their ethics statements. Several arguments, ranging from purely moralistic ones to essentially legal reasons, have been offered as a rationale for corporate ethics statements. Some observers believe that business is a profession similar to law or medicine and should regulate itself through codes of conduct. Two informed commentators have argued that the market mechanism and legal system are inadequate to regulate business behavior. The Nobel laureate economist, Kenneth Arrow (1974), indicated that externalities and information imbalances in business mean that society should impose restrictions of an ethical nature on business behavior. In his book, Where the Law Ends, lawyer and professor Christopher Stone (1975) postulated that the market and legal systems have limitations that must be overcome with more emphasis on ethical principles. The purpose of this research was to investigate

Journal of Business Ethics 14: 727-740, 1995. 1995 Kluwer Academic Publishers. Printed in the Netherlands.

728

Patrick E. Murphy

Corporate credo A corporate credo delineates a company's ethical responsibility to stakeholders and is usually a several paragraph statement outlining its ethical posture (Murphy, 1989). Probably the best known and most widely acclaimed corporate credo is Johnson & Johnson's. The J&J Credo discusses the company's responsibility to four stakeholder groups - customers (doctors, nurses and patients), employees, communities and stockholders. The aforementioned Penney Idea represents another good example of a corporate credo as well as one put forth by Champion International. The ten point "Champion Way" was created in 1981 as a statement of the corporate culture and was proposed as a guide for policy and action throughout the organization (McCoy and Twining, 1988). This credo helped guide that company through a recent restructuring and the firm was able to honor the credo's explicit call for commitment to employees by not firing anyone (Barrett, 1988). Corporate credos can serve as a benchmark document for firms which desire a cohesive corporate culture. A spirit of strong communication is essential if the credo's ideals are to be transmitted throughout the firm. One author (Murphy, 1989) has cautioned that a corporate credo is not usually precise enough to offer guidance for large multinational companies facing complex ethical issues and would probably not be useful for recently merged companies with disparate divisions.

the current status of corporate ethics statements of U.S.-based companies. The existence of such statements, when they were most recently revised and certain characteristics about them, was sought. Companies can demonstrate their commitment to ethics by both introducing ethics statements and using them as guideposts for corporate decisions. The paper is organized into four remaining parts. The first deals with background literature on value statements, corporate credos and codes o f ethics. The following sections cover the study's methodology and results. Conclusions and implications from this project regarding ethics statements are then offered.

Values statements A number of companies have set out their corporate values in a succinct statement that makes reference to quality, customer safety and employee issues. Values statements often stem from the firm's mission and give direction to it. While these statements are not exclusively devoted to ethics, they do provide an insight into how companies view ethical issues in relation to their operating principles. Bechtel Corporation's values statement provides a good illustration. It advocates that: "Values are the bedrock o f our corporate culture and reflect the organization's personality characteristics. They represent our corporate character reflecting the attitude of all the people of Bechtel." This preamble is followed by three points outlining corporate and employee values. Directives such as being ethical, reliable and fair; an emphasis on teamwork; mutual trust; and an open communicative environment are stressed. General Mills and Hewlett Packard also have a well-known corporate values statement. Values statements are intended to set out the guiding principles of the firm. If they are communicated widely, these values should be known throughout the organization. Companies like McDonalds, which espouse consistent values over time (usually based on the founder's ideals), are likely to be the ones where these statements will have the most impact.

Codes o f ethics These ethical statements are more detailed discussions of a firm's ethical policies. Codes commonly address issues like conflict of interest, relationships with competitors, privacy matters, gift giving and receiving, and political contributions. Most large U.S. companies have ethics codes in place and have revised them in recent years. These codes range in length from pamphlet size documents o f a couple pages to extensive booklets of over fifty pages (e.g., Boeing). Substantially greater analysis of ethics codes has

Ethics Statements: Current Status and Future Prospects

occurred than for either values statements or credos. Therefore, this section examines codes from several different viewpoints. First, the extensiveness of codes of ethics is discussed. Then, empirical studies of ethics codes are reviewed. Third, conceptual discussions and paradigms for designing effective codes are analyzed. Finally, the limitations and criticisms o f codes are noted.

729

Extensiveness of codes of ethics

In early surveys regarding the adoption of codes o f ethics, between 15 and 40 percent o f large companies had ethics codes in the 1950s and 60s (Futmer, 1969). Studies in the 1970s and 80s found that three-fourths of large companies had instituted formal ethics codes. The well cited Brenner and Molander (1977) update o f the classic Baumhaurt study indicated that 75 percent of their respondents endorsed ethical codes for their industries and firms. The Ethics Resource Center (1979) also found that about 75 percent of the responding companies did have codes, but generally they were lacking in specificity. White and M o n t g o m e r y (1980) determined that approximately 75 percent o f the firms they surveyed had a formal code of ethics. The Center for Business Ethics at Bentley College (1986) found that ninety-three percent of large corporations had a code in place. A Conference Board Survey (Berenbain, 1987) also reported that 76 percent o f companies had codes. In an update of their earlier surveys, the Center for Business Ethics (1992) found a consistent 93 percent of companies with an ethics code. The Conference Board's (Berenbain, 1992) results stood at 83 percent for firms in N o r t h America and Europe. It is safe to say that codes of ethics are c o m m o n place in almost all U.S. based large companies.

Empirical anaI},ses

Several projects have been conducted which examine various aspects of codes of ethics. White and M o n t g o m e r y (1980) found that a m u c h higher percentage of the biggest (defined as over

4 billion or more) companies had a code. In a content analysis of these codes, general statements of ethics and philosophy were covered in approximately 80% of the codes while conflict of interest was the most frequently addressed topic in the codes with over 70% having explicit discussion of this issue. Other frequently m e n tioned areas included compliance with applicable laws, political contributions, acceptance of gifts, and inside information. The authors concluded that much remained to be learned about designing and administering codes to measure their effectiveness. In a hard hitting analysis of late 1970s ethics codes introduced in response to Watergate and SEC investigations, Cressey and Moore (1983) argued that they had neither relieved organizational pressure to be unethical nor convinced opinion leaders that corporations have become more socially responsible. Their assessment was that few codes stress the importance o f senior management as role models. Furthermore, they contended that most code writers have greater confidence in their ability to administer surveillance procedures than in their abilities to generate an environment in which unethical conduct is practically unthinkable. During the late 1980s researchers in marketing examined codes to determine the extent o f marketing content in these documents. Hite et al., (1988) found that the topics covered most often in codes of conduct were misuse of funds/ improper accounting, conflicts of interest, political contributions, and confidential information. O f their top ten most frequently m e n t i o n e d topics, only one (business gifts/courtesies) could be interpreted as explicitly marketing related. O f these ten, four are really illegal rather then unethical activities. Their summary assessment was that only about 10% o f the codes they examined were labeled as excellent in terms of being very comprehensive and specific. R o b i n and his colleagues (1989) analyzed the content o f over 80 ethics codes and found three clusters: (1) Be a dependable organizational citizen; (2) Don't do anything unlawful or improper that will harm the organization; and (3) Be good to our customers. It is interesting to note that the classic "marketing concept" is one

730

Patrick E. Murphy

A professional manager should assist in maintaining the integrity and confidence of the business community. A professional manager should preserve the confidential nature of business and customer information. A professional manager should place the interests of the company ahead of any private interests and should disclose the facts in any situation where a conflict of interest may appear. A professional manager should avoid even the appearance of impropriety in business matters. A professional manager should be honest in dealing with the public and with the company's officers, directors, employees, experts and customers (Harris, 1978, pp. 355-378). Several other authors, all writing in the Journal of Business Ethics in the late 1980s, offered certain suggestions for improving codes o f ethics. Molander's (i987) extensive analysis presented a comprehensive list o f corporate arguments for an ethical code. He contended that a code should be communicated to all employees and organizational major client groups as welt as have a definite mechanism for enforcement. Weller (1988) proposed several testable hypotheses which emphasized priority setting, publicizing, and reporting violations to the code. He encouraged academics to examine codes and test his hypotheses. Within the context o f an article on "implementing business ethics," M u r p h y (1988) advocated that corporate codes should be: specific, public documents, blunt and realistic, and revised periodically. Benson (t989) provided a blueprint for improving usefulness o f codes o f ethics. His summary points were as follows: First, codes should be written in a manner designed to give the reasons for each order. Second, codes need beginnings and perhaps conclusions which try to secure support of the corporation or bureau team in a cooperative effort to keep the organization's actions strictly 'above board'. Third, codes would be welcome if they included provisions which recognized the responsibilities of management as well as the responsibilities of employees.

o f the three dominant clusters in ethics codes. For example, the Texaco code stated that the c o m p a n y strives "to deliver to customers only products o f proven high quality at fair prices and to serve t h e m in such a m a n n e r as to earn their continuing respect, confidence, and loyalty, both before and after the sale." These authors conclude that most codes are rule-based (e.g., legalistic in tone) rather then value-based. O n e other recent project (Edmonson, 1990) examined one hundred codes o f ethics. He found that the five most frequently appearing areas in codes o f ethics were: privacy and c o m m u n i c a tion; conflict o f interest; political contributions in the U.S.; company records; and gifts, favors and entertainment. Privacy issues n o w seem to have supplanted conflicts o f interest ( M o n t g o m e r y and White, 1980) as the most often discussed ethical issue in codes. Marketing topics such as relations with competitors, suppliers and customers are covered in over one-third o f these ethics codes. Additional marketing related concerns m e n t i o n e d in less than 20% o f these codes were products/service quality, the e n v i r o n m e n t and energy, and health/safety issues.

Conceptual analyses

M a n y academic and corporate spokespersons have c o m m e n t e d u p o n the efficacy and effectiveness o f w r i t t e n ethics codes. O n e o f the earliest and most insightful observers was then Harvard Business School D e a n R o b e r t Austin. He pointed out in t961 that a negative code o f ethics ("thou shah not") poses a n u m b e r o f problems: suspicion in the eyes o f the public; conflict o f interest for the manager; and the potential for finding loopholes. He argued for more specificity in codes o f conduct. In the most detailed conceptual examination o f codes o f ethics to date, Harris (1978) proposed a workable business code o f ethics modeled on the American Bar Association rules o f conduct and the American Medical Association code. He listed five cannons o f business responsibility support6d by ethical principles and rules o f conduct. The cannons were as follows:

Ethics Statements: Current Status and Future Prospects

Fourth, as codes become better means of ethical education, they should be publicized more, especially in areas near company factories or administrative headquarters. Fifth, the usefulness of codes depends on boards of directors and top management who want to keep their organizations ethical. In their recent book on ethics in marketing, Laczniak and Murphy (1993) offered five suggestions for an ideal code of ethics. Any code o f ethics should be: communicated (both to employees and to external stakeholders), specific (in terms of guidance), pertinent (to the industry), enforced (contain sanctions), and revised (updated periodically).

731

no enforcement mechanism is operative. The Ethics Resource Center (1990) has developed a list o f questions that companies should follow regarding the enforcement of codes. Codes witl no doubt be criticized in the future, but it does appear that firms have positively responded to these criticisms. More recent code revisions have attempted to overcome some of the limitations noted here.

Method

Instrument

'The method for examining the pervasiveness of ethics statements in U.S. corporations was a mail survey. Since a relatively large amount of information was desired from a national sample, a mail questionnaire was the only viable alternative. A four-page questionnaire was developed and pretested with a random sample o f corporate executives. Two respondents provided extensive comments for revising the instrument. The survey contained a combination of multiple choice, scaled and open-ended questions. They provided not only factual information about the existence of a code, credo or value statement, but also data regarding corporate training programs in ethics and demographic information about company size in terms of sales, number of employees and industry in which it operates.

Limitations and criticisms of codes of ethics

Codes of ethics have long been criticized for several reasons. First, many- of the early codes were critiqued for being too platitudinous or just " M o m and apple pie" statements. Some companies, unfortunately, believed that the public relations value was the most important aspect of their codes of ethics. A second criticism states that some codes are rather general and discuss topics that are not pertinent to its industry. Specifically, a generic code could be used interchangeably by ma W different firms because they cover virtually the same topics in a similar manner. A third criticism justifiably points out that no code can account for every conceivable ethical violation. Therefore, codes need to be specific and give examples of possible ethical violations but should be directive rather than inclusive. Another criticism is that codes tend to be too legalistic and just codify rules rather than provide moral guidance. A final criticism of codes of ethics is that they are not enforced. The comment, "they aren't worth the paper that the}, are printed on" is leveled at codes when meaningful sanctions do not exist. Anywhere from 10 to 30% o f companies who have codes of ethics do not have systems in place for dealing with violations (Leigh and Murphy; 1993). Therefore, companies and their codes are properly criticized if

Sample

The sample was contacted using the list of the Forbes 500 directory that was published in the April 27, 1992 issue of Forbes magazine. There were approximately 800 companies that made up this list. A personalized cover letter was addressed to the CEO of each company and signed by the researcher. The CEO was asked to route the survey to the person responsible for ethics training and code development in the firm. The packet included a cover letter directed to the respondent, the survey, a postage-paid reply envelope, and return postage-paid postcards to request an executive summary of the study for both the CEO and respondent.

732

Patrick E. Murphy

TABLE I Characteristics of responding companies

T h e survey was sent in early August o f 1992 and after an approximate cut-off o f two months 235 surveys were returned. In addition, 19 letters were received by the researcher from companies indicating they do not respond to any survey due to the large number o f requests. Three completed surveys were received after the cut-off date. The total response rate then was 257. This translates into a response rate o f approximately 32% in total with the usable response rate o f almost 30%. N o precontracts or reminders were used for cost reasons. This rate is approximately twice as high as several surveys conducted in recent years on the subject o f corporate ethics (Berenbeim, 1987, 1992; Touche Ross, 1988).

Major business category

Consumer packaged goods Diversified financial corporation Consumer products (durables) manufacturer Services corporation Industrial products manufacturer Retail corporation Other 6% 25% 3.5% 26.5% 20% 7% 12% 26% 16.5% 30% 17% 11.5% 27% 24% 28.5% 20.5% 39% 20% 19% 7% 6% 9%

Number of employees

Under 5 000 5 001-10 000 10 001-30 000 30 001-80 000 Over 80 000

Respondent characteristics

Table I lists the characteristics o f the responding firms and individuals. T h e responding firms tended to be concentrated more heavily in the services and financial industries. These c o m panies tend to be very large with the majority employing over 10 000 people. The responding firms are split almost evenly b e t w e e n those having under $4 billion in sales and those with more than that amount. Furthermore, the areas with responsibility for ethics seems to be primarily in the human resources and training areas, but a significant minority o f firms do house their ethics program within the legal department. To test for nonresponse bias, forty companies from the Forbes list were contacted via telephone. These nonresponding firms were slightly smaller in size (54% had less than 10 000 employees) and in terms o f sales (30% with $1 billion or less). Almost as many o f these firms had a formal code (86%) as the firms w h o responded to the survey (91%). Therefore, responding companies do not appear to be significantly different from those w h o did not reply.

Approximate annual sales

$1 billion or less $2-3 billion $4-9 billion $10 billion or more

Functional responsibility

Human resources Legal Training Auditing Ombudsman Other

Results a n d discussion

Table II shows this study's results regarding the existence and perceived characteristics o f corporate ethics statements. As expected, a very

large percentage (91%) o f these companies have a written code o f ethics. In addition, just over half o f these firms have a values statement (53%), while about one-third have a corporate credo (34%). O f the 235 responding companies, a total o f 49 indicated that they have all three. Values statements tend to be relatively new documents in the majority o f companies with half o f t h e m introduced in the last five years and almost 80% within the past ten years. A r o u n d forty percent o f the credos were introduced less than five years ago, but it is interesting to note that about 20% have been in existence for over 20 years. This means that Johnson & Johnson and J.C. Penney were not the only firms to recognize early on that adopting a credo was a way to institutionalize corporate ethics. About twothirds o f the codes were introduced during the

Ethics Statements: Current Status and Future Prospects

733

TABLE II Corporate ethics statements in U.S. firms

Does" your company have a formal written

Corporate credo Code of ethics Values statement

When were these documents first introduced? C~do Code

34% 91 53

Valu~ statement

Less than 5 years ago 5-10 years ago 11-20 years ago Over 20 years ago

When were they most recently revised?

41% 23 14 22 19% 25 25 31

18.5% 34.5 31.5 15.5 18% 14 31 37

51% 27.5 13.5 8 17% 18 32 33 53% 47

Before '90 90 91 92

How are they communicated?

Only to employees Both internally and external

Does your written code of ethics

Yes 36% 80 84

~ro

Emphasize mostly information pertinent to your industry rather than general issues Include sanctions (e.g., reprimand to loss of job) for violating the code Contain specific guidance on gift giving and receiving ($ amounts or other detailed information)

64% 2O 16

1970s and 80s. These companies appeared to respond either to the well publicized business scandals o f that era or the need to set d o w n explicit ethical policies during this growth period for most firms. A n o t h e r topic covered in Table II pertains to w h e n these d o c u m e n t s were most recently revised. Just under 20% stated that their credo, code or values statement had been revised prior to 1990. The 1990s have seen substantial revision activity for all three types o f ethics statements with over 30% o f the responding firms' ethics statements being revised in 1992. T h e importance o f communicating the formal policy statements on ethics to employees and stakeholders was noted by several writers (Benson, 1989; Molander, 1987; Murphy, 1988). Table II also shows that just over half o f these firms (53%) communicate their corporate ethics statements only to employees while the remain-

ing companies make them available to outsiders as well. Several (four) respondents wrote on tile survey that they share the documents just with their vendors. It is somewhat surprising to see that the majority o f firms still treat ethics staternents as exclusively internal documents. Since codes o f ethics are the best k n o w n and most extensively studied (see codes section) type o f ethics statements, more information was sought about them. The results from three characteristics o f codes are shown at the b o t t o m o f Table ti. Codes have long been criticized for being too general and containing primarily "boilerplate" information. It appears that this criticism still holds because only 36% o f the responding firms indicated that the information in the codes is pertinent to their industry. O n the other hand, 80% do include explicit reference to sanctions for code violations. A n even greater percentage (84%) give specific guidance about

734

Patrick E. Murphy Pertinent

Table IV shows the responses pertaining to whether the code emphasizes information pertinent to the industry or relies primarily on general issues. Only the business category and functional responsibility areas yielded significant results. Companies classified as other (e.g., conglomerates w h o tabel themselves diversified companies) and consumer packaged goods firms were least likely to include information pertinent to their industry. Also, w h e n the legal department or other areas whose focus is not on human resources (i.e., ombudsman, corporate secretary, auditing, operations or public relations) have responsibility- for the code, it is probably more general in scope. This finding may be due to the fact that personnel and training people see greater value in having more pertinent information available in order to give the employee explicit direction in matters of ethics. It should be noted that in only one category in Table IV (retail corporations) did the affirmative response exceed 50 percent and may represent an understanding by these firms that their industry does have several unique characteristics that should be reflected in the code.

gift giving and receiving. This practice was selected because virtually all codes make reference to this practice and code writers have been chastised in the past for not offering useful directions to employees on this c o m m o n business custom. Further analysis was conducted on the information shown in Tables I and II. Specifically, the results were analyzed using business category, number o f employees, annual sales and job responsibility of the respondent as the independent variables. No differences were found using these variables for the existence or absence of a credo, code and values statement, and the time period when these documents were first introduced. Since the findings were so similar for the revision of these statements, further analysis was not undertaken because any differences would not be meaningful. The balance of this section investigates several suggested ideal characteristics for ethics statements: communicated, pertinent, enforced (sanctions) and specific.

Communicated

Table III depicts the responding companies' policies regarding communication of these statements. A significant difference was found for three of the four organizational characteristics. In the business category, financial institutions are the least likely to publicly disseminate their ethics statements. The largest firms are slightly more prone to communicating their ethics policies both internally and externally. As one would expect, if the legal department has jurisdiction for the ethics function, it is likely to be communicated only within the company. T h e disparity between the legal and training areas' views toward communication is dramatic. This finding probably reflects a philosophical difference between the legalistic approach where companies should be careful not to divulge corporate documents to the public and the training approach which often promotes openness in communication.

Enforced

Table V indicates that annual sales and functional responsibility are related to the inclusion of sanctions for code violations. Most responding companies (80%) state that they do have sanctions in place. Somewhat interestingly, it is the $4-$9 billion firms that are most likely to have such enforcement policies and the largest companies ($10 billion or more) were least likely to have them. It may be that once a firm gets to be so large that it is difficult to produce meaningful sanctions that can be administered companywide. Those firms where the legal department has functional responsibility are somewhat more likely to include sanctions. This finding would seem to follow from their more legalistic interpretation of codes.

Ethics Statements: Current Status and Future Prospects

TABLE III Communication of ethics statements Employees only

735

Both internal and external

Major business category

Consumer packaged goods Diversified financial corporation Consumer products (durables) manufacturer Services corporation Industrial products manufacturer Retail corporation Other 33% 77 50 50 37 40 60 67% 23 50 50 63 60 40 X 2 = 20.5 ~ 39% 35 50 56 63 X 2 = 7.4 d 45% 43 54 58 X 2 = 2.5 49% 28 61 52 X 2 = 9.5 b

Number of employees

Under 5 000 5 001-10 000 10 001-30 000 30 001-80 000 Over 80 000 61% 65 50 44 37

Approximate annual sales

$1 billion or less $2-3 billion $4-9 billion $10 billion 55% 57 46 42

Functional responsibility

Human resources Legal Training Other 51% 72 39 48

Significant at 0.001 level. b Significant at 0.01 level. c Significant at 0.05 level. d Significant at 0.1 level.

Speci c

Table VI lists the results regarding whether the code contains specific guidance on gift giving and receiving. Only for the annual sales variable were the results significant. O n c e again (recall Table V), the $4-$9 billion firms were the most likely (96%) to offer specific guidelines. In this instance, the largest firms did follow closely behind with 90% providing guidance while the smaller firms were least likely to give it. It is

n o t e w o r t h y to m e n t i o n that 100% o f the responding c o n s u m e r durabtes manufacturers (n = 7) and retailers (n = 14) answered this question affirmatively. W h i l e the number o f respondents is small, it does give an indication that firms in these industries feel that such guidance is helpful for their marketing and other personnel. For example, the retail buyer, w h o is expected to do m u c h entertaining and travel, is a position w h e r e companies likely need to formalize their policies in the code.

736

Patrick E. Murphy

TABLE IV Codes emphasized pertinent industry statements Yes No

Major business category

Consumer packaged goods Diversified financial corporation Consumer products (durables) manufacturer Services corporation Industrial products manufacturer Retail corporation Other 18% 45 29 45 30 54 12 82% 55 71 55 70 46 88 X 2 = 14.9 b 51% 69 67 72 72 X 2 = 6.3 60% 73 75 66 X 2 = 3.07 55% 73 59 80 X 2 = 8.9 ~

Number of employees

Under 5 000 5 001-10 000 10 001-30 000 30 001-80 000 Over 80 000 49% 3t 33 28 28

Approximate annual sales

$1 billion or less $2-3 billion $4-9 billion $10 billion 40% 27 25 34

Functional responsibility

Human resources Legal Training Other 45% 27 41 20

Significant at 0.001 level. b Significant at 0.01 level. c Significant at 0.05 level. d Significant at 0.1 level.

Conclusions and implications

Several conclusions from this study can be drawn. T h e y are: 1. Corporate ethics statements are being revised (Table I). C E O s and other high level company executives n o w appear to realize that credos, codes and value statements are not the Ten C o m m a n d m e n t s and need to be updated to reflect the changing

and complex competitive world o f the 1990s. . Ethics policies are not widely disseminated beyond the firm. Since less than half o f the responding companies share their code w i t h external stakeholders, one could conclude that these documents emphasize legal restrictions and company procedures rather than ethical issues. W h e n the legal department has jurisdiction for the ethics statements (Table II), they are usually

Ethics Statements: Current Status and Future Prospects

TABLE V Inclusion of sanctions for code violation Yes No

737

Major business category

Consumer packaged goods Diversified financial corporation Consumer products (durables) manufacturer Services corporation Industrial products manufacturer Retail corporation Other 73% 83 71 83 74 79 84 27% 17 29 17 26 21 16 X 2 ~- 2.5 15% 25 16 20 36 X 2 = 5.9 20% 25 10 37 X 2 = 10.0 b 24% 7 27 23 X 2 _~ 5.98 a

Number of employees

Under 5 000 5 001-10 000 10 001-30 000 30 001-80 000 Over 80 000 85% 75 84 80 64

Approximate annual sales

$1 billion or less $2-3 billion $4-9 billion $10 billion 80% 75 90 63

Functional responsibility

Human resources Legal Training Other 76% 93 73 77

Significant at 0.001 level. b Significant at 0.01 level. c Significant at 0.05 level. d Significant at 0.1 level.

shared only with employees. Therefore, they may be more appropriate labeled "legal" rather than "ethical" codes. . Most codes are not tailored to industry issues. This finding (see Tables I and IV) lends credence to the view that codes are still rather broad in scope and to not deal directly with industry-specific problems. If these codes are to offer guidance for marketing and other personnel, they should go beyond generic issues like conflict o f

interest and confidentiality and deal with return policies for mail order firms and advertising issues (i.e., media selection) for consumer products' companies. . Most codes contain some reference to sanctions for violating it (Tables I and V). N o t surprisingly, legal departments appear to be most likely to make certain that their company's code is enforced. A troubling finding here is that 20 percent o f the firms do not have sanctions in place. Lack o f a

738

Patrick E. Murphy

TABLE VI Specific guidance on gifts Yes No

Major business category

Consumer packaged goods Diversified financial corporation Consumer products (durables) manufacturer Services corporation Industrial products manufacturer Retail corporation Other 73% 87 100 78 81 100 84 27% 13 0 22 19 0 16 X 2 = 7.1 15% 25 16 20 36 X 2 = 5.9 34% 21 4 10 X 2= 16.8" 19% 5 16 16 X 2 = 4.29

Number of employees

Under 5 000 5 001-10 000 10 001-30 000 30 001-80 000 Over 80 000 85% 75 84 80 64

Approximate annual sales

$1 billion or less $2-3 billion $4-9 billion $10 billion 66% 79 96 90

Functional responsibility

Human resources Legal Training Other 81% 95 84 84

Significant at b Significant at Significant at Significant at

0.001 level. 0.01 level. 0.05 level. 0.1 level.

proper enforcement mechanism indicates that the codes "lack teeth" and in certain instances may be guilty o f the charge that they are primarily still public relations documents. . Codes do offer specific guidance in terms o f gift giving and receiving (Tables I and VI). This situation appears to be an improvement over the past w h e n employees were often encouraged to not give or take gifts o f more than a " n o m i n a l " amount.

T h e question remains, however, w h e t h e r this specific guidance carries over to other areas o f the firm's operation. Implications w h i c h follow from these conclusions can also be drawn for managers and researchers. Managerial Implications - Companies should continue to revise and update their ethics statements. The evaluation of these documents should occur throughout the firm. Furthermore, efforts

Ethics Statements: Current Status and Future Prospects

should be undertaken to disseminate codes to all stakeholders. A benefit to broader availability is that such action pubticly demonstrates a commitment to ethics. By not communicating them beyond the firm, it looks like the company may have something to hide. Executives should also examine their codes in terms of its pertinence to the industry. A good exercise would be to procure several competitors codes and ones from other well known companies. If they all look the same, the code should undergo substantial revision. Ira firm's code does not contain sanctions, they should be included. A range of sanctions should be offered. For example, padding an expense account for the first time should probably warrant a reprimand while sharing confidential information with a cornpetitor might warrant dismissal. Finally, managers should offer specific guidance where possible to help the employees understand the position of the firm on gifts and other matters. Research Implications - Researchers could extend this study in several ways. First, the extensiveness of ~he revisions to the ethics statements should be studied. Are these recent revisions just slight modifications or wholesale revisions? How often are serious revisions done? Second, to which stakeholders do companies disseminate their codes? If they are onIy communicated to employees, why is this policy followed? Third, why do most firms resist making their codes more pertinent to their line of business? Is it too difficult or are top managers .just more comfortable with broad, general codes? Fourth, what is the experience of firms with code enforcement? Is it more difficult for firms who do not have sanctions included to get their codes to be taken seriously? Fifth, what other areas in addition to gift giving warrant specific treatment in codes? Are these guidelines useful or constraining for international operations? Finally, can companies realistically use just a single ethics statement to cover all global operations (Robertson and Schlegelmitch, 1993)? Are revisions or adjustments necessary to conduct business in certain markets? tn the final analysis, there are several positive results from this survey - most companies have codes or other ethics statements, they have been recently revised, and they do usually contain sanctions and specific guidance regarding gifts. However, the fact that these documents are not widely communicated and do not contain extensive pertinent industry i n f o r m a t i o n in t h e m

739

means that there is still room for improvement in the corporate ethics statements. C o n t i n u e d discussion and analysis o f the ethics policies not only w i t h i n executive suites but also plant locations t h r o u g h o u t the world should lead to better statements and more ethical corporate cultures in the future.

References

Arrow, K. J.: 1973, 'Social Responsibility and Economic Efficiency', Public Policy 21, 303-317. Austin, R. W.: 1961, 'Code of Conduct for Executives', Har~ard Business Review (Sept.-Oct.), 53-61. Barrett, T.: i988, 'Business Ethics for Sale', .Newsweek (May 9), 56. Bennett, A.: 1988, 'Ethics Codes Spread Despite Skepticism', The Wall Street Journal (July 15), 13. Benson, G. C. S.: 1989, 'Codes of Ethics', Journal of Business Ethics (May), 317-318. Berenbeim, R. E.: 1987, Corporate Ethics, New York: The Conference Board, Report No. 900. Berenbeim, R. E.: 1992, Corporate Ethics Practices, New York: The Conference Board, Report No. 986. Brenner, S. N. and E. A. Molander: 1977, 'Is the Ethics of Business Executives Changing?', Harvard Business Review 55 (Jam-Feb.), 57-71. Business Roundtabte: 1988, Corporate Ethics: A Prime Business Asset, New York. Center for Business Ethics: 1986, 'Are Corporations Institutionalizing Ethics?' Journal of Business Ethics 5, 85-91. Center for Business Ethics: 1992, 'Instilling Ethical Values in Large Corporations', .Journal of Business Ethics 11 (Nov.), 863-868. Cressey, D. R. and C. A. Moore: 1983, 'Managerial Values and Corporate Codes of Ethics', California Management Review 25 (Summer), 53-77. Edmonson, W. E: 1990, A Code of Ethics: Do Corporate Executives And Employees Need It? (Itawamba Community College Press, Fulton, MS). Ethics Resource Center: 1979, Codes of Ethics in Corporations and Trade Associations and the Teaching of Ethics in Graduate Business Schools (Opinion Research Corporation, Princeton, NJ). Ethics Resource Center: 1990, Creating a Workable Company Code of Ethics. Fulmer, R. M.: 1969, 'Ethical Codes for Business', Personnel Administration (May-June), 49-57.

740

Patrick E. Murphy

Instructions for Marketers', Journal of Business Ethics 11 (Dec.), 921-930. Oliverio, M. E.: 1989, 'The Implementation of a Code of Ethics: The Early Effort of One Entrepreneur',Journal of Business Ethics 8, 367-374. Robertson, D. C. and B. B. Schlegelmilch: 1993, 'Corporate Institutionalization of Ethics in the United States and Great Britain', Journal of Business Ethics 12 (April), 301-312. Robin, D., M. Giallourakis, F. R. David, and T. E. Moritz: 1989, 'A Different Look at Codes of Ethics', Business Horizons ~an.-Feb.), 66-73. Stone, C.: 1975, Where the Law Ends (Harper & Row: New York), pp. 88-110. Tsalikis, J. and D. J. Fritzsche: 1989, 'Business Ethics: A Literature Review with a Focus on Marketing Ethics', Journal of Business Ethics 8, 695-743. Touche R.: 1988, Ethics in American Business, New York, January. Weller, S.: 1988, 'The Effectiveness of Corporate Codes of Ethics', Journal of Business Ethics 7 (May), 389-396. White, B. J. and B. R. Montgomery: 1980, 'Corporate Codes of Conduct', California Management Review (Winter), 80-87.

Harris, C. E.: 1978, 'Structuring A Workable Business Code of Ethics', University of Florida Law Review 30, 310-382. Hite, R. E., J. A. Bellizzi and C. Fraser: 1988, 'A Content Analysis of Ethical Policy Statements Regarding Marketing Activities',Journal of Business Ethics 7 (Oct.), 771-776. Hyman, M. R., R. Skipper and R. Tansey: 1990, 'Ethical Codes are Not Enough', Business Horizons (March/April), 15-22. Laczniak, G. R. and P. E. Murphy: 1993, Ethical Marketing Decisions: The Higher Road (Allyn & Bacon, Boston). Leigh, J. H. and P. E. Murphy: 1993, 'The Role of Formal Policies and Informal Culture on Ethical Decision Making by Marketing Managers', Working paper, Texas A & M University. McCoy, C. S. and F. N. Twining: 1988, 'The Corporate Values Program at Champion International', in Corporate Ethics: A Prime Business Asset (The Conference Board, New York), pp. 21-30. Molander, E. A.: 1987, 'A Paradigm for Design, Promulgation and Enforcement of Ethical Codes', Journal of Business Ethics 6 (Nov.), 619-632. Murphy, E E.: 1988, 'Implementing Business Ethics', Journal of Business Ethics 7 (Dec.), 907-916. Murphy, P. E.: 1989, 'Creating Ethical Corporate Structures', Sloan Management Review 30 (Winter), 61-67. O'Boyle, E. J. and L. E. Dawson, Jr.: 1992, 'The American Marketing Association Code of Ethics:

University of Notre Dame, Department of Marketing, Notre Dame IN, 46556, U.S.A.

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5794)

- Nakajima - Use of Sky BrightnessDokumen15 halamanNakajima - Use of Sky BrightnessCarlos MonakosBelum ada peringkat

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- First Record - Silva 200Dokumen3 halamanFirst Record - Silva 200Carlos MonakosBelum ada peringkat

- Purification of C-PhycocyaninDokumen11 halamanPurification of C-PhycocyaninCarlos MonakosBelum ada peringkat

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- Review Essay: Working With CynicismDokumen5 halamanReview Essay: Working With CynicismCarlos MonakosBelum ada peringkat

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (895)

- 08 oDokumen11 halaman08 oCarlos MonakosBelum ada peringkat

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (344)

- 19 Antibodies To West Nile Virus in Equinesv23n4a07Dokumen9 halaman19 Antibodies To West Nile Virus in Equinesv23n4a07Carlos MonakosBelum ada peringkat

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (399)

- Net - of - Faith by Peter ChelcickýDokumen166 halamanNet - of - Faith by Peter ChelcickýCarlos MonakosBelum ada peringkat

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (588)

- 06 Mamiferos Selva de ZoqueDokumen17 halaman06 Mamiferos Selva de ZoqueCarlos MonakosBelum ada peringkat

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- 07 Terrestrial and Aquatic Mammals of The PantanalDokumen14 halaman07 Terrestrial and Aquatic Mammals of The PantanalCarlos MonakosBelum ada peringkat

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (266)

- 03 LIMA, Regina Aparecida Garcia De. Palliative CareDokumen2 halaman03 LIMA, Regina Aparecida Garcia De. Palliative CareCarlos MonakosBelum ada peringkat

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- Net - of - Faith by Peter ChelcickýDokumen166 halamanNet - of - Faith by Peter ChelcickýCarlos MonakosBelum ada peringkat

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- A Solemn Review of The Custom of War by Noah WorcesterpdfDokumen14 halamanA Solemn Review of The Custom of War by Noah WorcesterpdfCarlos MonakosBelum ada peringkat

- 10662241211199960Dokumen19 halaman10662241211199960Carlos MonakosBelum ada peringkat

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (73)

- Non-Resistance Asserted by Daniel MusserDokumen63 halamanNon-Resistance Asserted by Daniel MusserCarlos MonakosBelum ada peringkat

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- Non-Resistance Asserted by Daniel MusserDokumen63 halamanNon-Resistance Asserted by Daniel MusserCarlos MonakosBelum ada peringkat

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- The Early Christian Attitude To War by C. J. CadouxDokumen186 halamanThe Early Christian Attitude To War by C. J. CadouxCarlos MonakosBelum ada peringkat

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2259)

- The 3CDokumen4 halamanThe 3CPankaj KumarBelum ada peringkat

- MGMT 324 Midterm Study Guide Summer 2018Dokumen12 halamanMGMT 324 Midterm Study Guide Summer 2018أبومراد أبويوسفBelum ada peringkat

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- TrimaxdrhpDokumen348 halamanTrimaxdrhpArjun ArikeriBelum ada peringkat

- Strategic Management ModelsDokumen24 halamanStrategic Management ModelsAnubhav DubeyBelum ada peringkat

- One Point LessonsDokumen27 halamanOne Point LessonsgcldesignBelum ada peringkat

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- Jis B 1196Dokumen19 halamanJis B 1196indeceBelum ada peringkat

- Paying Quantities Key & Charest - CLE - Oil and Gas Disputes 2019Dokumen22 halamanPaying Quantities Key & Charest - CLE - Oil and Gas Disputes 2019Daniel CharestBelum ada peringkat

- DNV GL enDokumen2 halamanDNV GL enSreegith ChelattBelum ada peringkat

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- Students Satisfaction On The Services Provided by The School Canteens in Catanduanes State UniversityDokumen31 halamanStudents Satisfaction On The Services Provided by The School Canteens in Catanduanes State UniversityAnthony HeartBelum ada peringkat

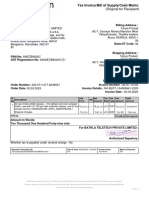

- InvoiceDokumen1 halamanInvoicetanya.prasadBelum ada peringkat

- Exclusive Legislative ListDokumen4 halamanExclusive Legislative ListLetsReclaim OurFutureBelum ada peringkat

- TCI Letter To Safran Chairman 2017-02-14Dokumen4 halamanTCI Letter To Safran Chairman 2017-02-14marketfolly.comBelum ada peringkat

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (120)

- Pricing Concepts & Setting The Right PriceDokumen33 halamanPricing Concepts & Setting The Right PriceNeelu BhanushaliBelum ada peringkat

- Kabushi Kaisha Isetan Vs IacDokumen2 halamanKabushi Kaisha Isetan Vs IacJudee Anne100% (2)

- CAS 610 Using Internal Auditor PDFDokumen11 halamanCAS 610 Using Internal Auditor PDFLIK TSANGBelum ada peringkat

- Bookkeeping Problems Batch 1Dokumen2 halamanBookkeeping Problems Batch 1lanz kristoff racho100% (1)

- Poliform Kitchens Aust (855KB) PDFDokumen12 halamanPoliform Kitchens Aust (855KB) PDFsage_9290% (1)

- Test 1 MCQDokumen3 halamanTest 1 MCQKarmen Thum50% (2)

- Utility BillDokumen1 halamanUtility BillIsaiah Kipyego0% (1)

- CASESTUDYDokumen21 halamanCASESTUDYLouise Lopez AlbisBelum ada peringkat

- Contract For Services Law240Dokumen5 halamanContract For Services Law240Izwan Muhamad100% (1)

- Eco-Bend: CNC Hydraulic Press BrakeDokumen9 halamanEco-Bend: CNC Hydraulic Press Brakehussein hajBelum ada peringkat

- A Study On Consumer Behavior Regarding Investment On Financial Instruments at Karvy Stock Broking LTDDokumen88 halamanA Study On Consumer Behavior Regarding Investment On Financial Instruments at Karvy Stock Broking LTDBimal Kumar Dash100% (1)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)

- Case StudyDokumen4 halamanCase Studychandu1113Belum ada peringkat

- El 1204 HHDokumen6 halamanEl 1204 HHLuis Marcelo HinojosaBelum ada peringkat

- Coursera Branding and Customer ExperienceDokumen1 halamanCoursera Branding and Customer Experienceambuj joshiBelum ada peringkat

- Database PanteneDokumen4 halamanDatabase PanteneYahya CahyadiBelum ada peringkat

- Capital Gains TaxDokumen5 halamanCapital Gains TaxJAYAR MENDZBelum ada peringkat

- Employee Motivation and Retention ProgrammeDokumen2 halamanEmployee Motivation and Retention ProgrammeHarish Kumar100% (1)

- Lilly Ghalichi, Lilly Lashes Sued For 10 Million DollarsDokumen33 halamanLilly Ghalichi, Lilly Lashes Sued For 10 Million DollarsAll Glam Everything100% (1)