The Relationship Between The Big Five Personality Traits and Academic Motivation

Diunggah oleh

paradiseseeker35Deskripsi Asli:

Judul Asli

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

The Relationship Between The Big Five Personality Traits and Academic Motivation

Diunggah oleh

paradiseseeker35Hak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Personality and Individual Dierences 39 (2005) 557567

www.elsevier.com/locate/paid

The relationship between the big ve personality traits and academic motivation

Meera Komarraju

a b

a,*

, Steven J. Karau

b,*

Department of Psychology, Southern Illinois University, Carbondale, IL 62901-6502, United States Department of Management, Southern Illinois University, Carbondale, IL 62901-4627, United States Received 29 April 2004; received in revised form 14 December 2004; accepted 14 February 2005 Available online 12 April 2005

Abstract Understanding the relationship between personality characteristics and academic motivation may be central to developing more eective teaching strategies. The current research examined the relationship between the Big Five personality traits and individual dierences in college students academic motivation. Individuals (172 undergraduates) were asked to complete the NEO Five Factor Inventory (Costa & McCrae, 1992) and the Academic Motivations Inventory (AMI; Moen & Doyle, 1977). Results revealed a complex pattern of signicant relationships between the Big Five traits and the 16 subscales of the AMI. Stepwise (forward) multiple regressions further claried the relationships between personality and three core factors of the AMI (engagement, achievement, and avoidance). Specically, engagement was best explained by Openness to experience and Extraversion. Achievement was best explained by Conscientiousness, Neuroticism, and Openness to experience. Finally, avoidance was best explained by Neuroticism, Extraversion, and by an inverse relationship with Conscientiousness and Openness to experience. Results are interpreted in terms of creating an appropriate t between teaching modalities and individual dierences in students academic motivation due to personality traits. Directions for future research and educational practice are considered. 2005 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Big ve; Personality traits; Academic motivation

Corresponding authors. Tel.: +1 618 453 3543; fax: +1 618 453 3563 (M. Komarraju). E-mail addresses: meerak@siu.edu (M. Komarraju), skarau@cba.siu.edu (S.J. Karau).

0191-8869/$ - see front matter 2005 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2005.02.013

558

M. Komarraju, S.J. Karau / Personality and Individual Dierences 39 (2005) 557567

1. Introduction Individuals dier in their learning styles and educational preferences. These individual dierences provide important clues about how best to design educational oerings. Students also dier in the level of motivation they display in the classroom. Some approach learning opportunities with enthusiasm and an intrinsic desire to know more while others seem bored and uninterested. There are various factors, both personal and contextual, that explain these dierences (Stipek, 2002). While a number of studies have examined individual dierences in learning styles, thinking styles, academic achievement, and academic success, few have focused on individual dierences in academic motivation. Yet, academic motivation is a key determinant of academic performance and deserves closer attention (Linnenbrink & Pintrich, 2002). The current research was designed to examine how the Big Five personality traits may relate to individual dierences in academic motivation. 1.1. Theoretical background Several general perspectives on learning suggest reasons why personality should relate to motivation. First, research has demonstrated that students can be either intrinsically or extrinsically motivated, with some students displaying intellectual curiosity and others remaining disengaged (Deci & Ryan, 1985). Second, research on individual dierences in learning styles (e.g., Biggs, 1993) suggests that students approach learning with either a surface, deep, or achieving style. Third, Dweck and Leggett (1988) have oered a theory suggesting implicit theories of intelligence inuence students academic performance goals. Similarly, Elliot and McGregor (1999) have emphasized that anxiety can aect learning goals and performance. Finally, research regarding multiple types of intelligence (e.g., Gardner, 1983; Sternberg, Tor, & Grigorenko, 1998) suggests that students who are taught in a way that matches their abilities are likely to achieve at higher levels. These views converge to suggest that the degree of match between the academic environment and student learning preferences related to personality should be related to academic motivation. 1.2. Literature review While a number of studies have examined individual dierences in academic performance, most have focused on academic achievement rather than motivation. Moreover, much of the existing motivation research has focused on elementary, middle, and high school students rather than college students. The relevant research on academic issues that may be related to personality and motivation in college students has focused on: (a) personality and academic performance, (b) personality and learning styles, and (c) personality and motivation. Personality and academic performance. Prior research indicates that the Big Five traits (Neuroticism, Extraversion, Openness, Conscientiousness, and Agreeableness) reect core aspects of human personality and have strong inuences on behavior (Costa & McCrae, 1992). Some studies have specically examined the role of the Big Five in predicting academic success. Conscientiousness has consistently and positively predicted examination performance (Chamorro-Premuzic & Furnham, 2003), as well as grade point average (GPA) and academic success (Busato, Prins,

M. Komarraju, S.J. Karau / Personality and Individual Dierences 39 (2005) 557567

559

Elshout, & Hamaker, 2000). Openness is positively related to nal grades, with high scorers using learning strategies that emphasize critical thinking (Lounsbury, Sundstrom, Loveland, & Gibson, 2003). In addition, Neuroticism is related to reduced academic performance (Chamorro-Premuzic & Furnham, 2003), whereas Agreeableness is positively associated with grades (Farsides & Woodeld, 2003). Entwistle and Entwistle (1970) found that stable introverts using good study methods achieved higher performance than extraverts or emotionally unstable students, whereas Furnham and Medhurst (1995) showed a signicant positive correlation between sociability and performance in a seminar class. Other studies have focused on additional personality traits, as well as on emotional and social factors. Pritchard and Wilson (2003) report that perfectionists had higher GPAs and tended to stay in school, whereas students with low self-esteem were more likely to drop out. Other studies have also found a negative correlation between emotional instability and academic performance (Furnham & Mitchell, 1991; Heaven, Mak, Barry, & Ciarrochi, 2002). Work drive has been reported to account for signicant variance in GPA, beyond that explained by intelligence and the Big Five traits (Lounsbury et al., 2003). Additional research has identied achievement, dominance, exhibitionism, and self-control as signicant predictors of classroom performance (Rothstein, Paunonen, Rush, & King, 1994; Wolfe & Johnson, 1995). In an interesting meta-analysis, Ackerman and Heggestad (1997) found some modest relationships between personality and intellectual ability measures. For example, Openness was positively related to intellectual ability, whereas Neuroticism, psychoticism, and test anxiety were negatively related to intellectual ability. These researchers concluded that intellectual abilities, interests, and personality are interrelated and that intellectual ability level and personality traits determine success, whereas interest determines task motivation. Personality and learning styles. A few studies have examined the importance of self-condence and self-esteem in explaining individual dierences in learning styles. Abouserie (1995) and Schmeck and Geisler Brenstein (1991) found that students with high self-esteem and high achievement motivation preferred a deep processing learning style. In contrast, students with low self-esteem and self-doubt preferred a surface processing style. Similarly, Livengood (1992) found that students who had high condence in their intelligence preferred learning rather than performance goals and preferred professors who emphasized learning. Several studies highlight the importance of adjusting the learning environment to match individual dierences. Furnham (1992) found that extraverts tend to be more active than reective, whereas introverts are more reective. Individuals high on psychoticism preferred to evaluate information intuitively, whereas individuals low on psychoticism used systematic processing. Zhang (2002, 2003) found that conscientious and open individuals preferred a deep learning style emphasizing mastery, whereas neurotic students preferred a surface learning style. Agreeableness was negatively associated with an achieving style emphasizing high grades. Regarding thinking styles, Openness was positively associated with thinking styles emphasizing being open-minded and perceptive, whereas Neuroticism was strongly associated with thinking styles emphasizing structured environments. Additional research also highlight the importance of matching preferred learning strategies with complementary teaching techniques (e.g., De Raad & Shouwenburg, 1996; Riding & Wigley, 1997; Vermetten, Lodewijks, & Vermunt, 2001). Personality and motivation. Some studies have examined personality variables that may be related to aspects of academic motivationsuch as achievement motivation, performance goals,

560

M. Komarraju, S.J. Karau / Personality and Individual Dierences 39 (2005) 557567

and test anxietyand related these variables to academic performance. For example, Heaven (1989) reported that achievement motivation was positively correlated with extraversion, and negatively correlated with impulsiveness and psychoticism among high school students. Busato, Prins, Elshout, and Hamaker (1999) reported that conscientious and extraverted students were more achievement oriented and preferred meaning, reproduction, and application directed learning styles. In contrast, students high on Neuroticism and fear of failure had low achievement motivation, exhibited an undirected learning style, and had diculty in identifying and processing what material was important. Focusing on adaptive and maladaptive behaviors of students in performance settings, Dweck and Leggett (1988) found that students who viewed intelligence as a xed entity adopted performance-related goals and gave up when faced with obstacles, whereas students who viewed intelligence as malleable adopted learning goals and persisted in the face of diculties. Kanfer, Ackerman, and Heggestad (1996) found that need for achievement was positively correlated with a composite measure of motivation, and test anxiety was positively correlated with Neuroticism. Finally, in examining test anxiety as a trait in relation to performance-approach and performance-avoidance goals, Elliot and McGregor (1999) found students adopting performance-avoidance goals were more likely to perform poorly on exams and that worry mediated this relationship. 1.3. The current study Although prior research has provided valuable information on relationships between various personality traits and selected aspects of academic motivation, such as performance goals and learning styles, very little research has examined the relationship between the Big Five traits and multiple academic motives. The current study was designed to address this need by directly assessing the relationship between the Big Five personality traits and academic motivation. To allow us to measure multiple aspects of academic motivation, we used the Academic Motivations Inventory (AMI, Doyle & Moen, 1978; Moen & Doyle, 1977), which includes 16 subscales assessing a wide variety of academic motivations. We based our predictions on the logic that students would be most motivated by academic environments that provide a good t with their personality traits. This logic is consistent with prior research and theory on intrinsic motivation (Deci & Ryan, 1985), individual dierences in learning styles (e.g., Biggs, 1993), implicit theories of intelligence (Dweck & Leggett, 1988), and multiple types of intelligence (Gardner, 1983). Our specic hypotheses regarding each Big Five dimension and academic motivation were based both on an analysis of how the characteristics already known to reect these dimensions (e.g., Costa & McCrae, 1992) would logically relate to matching educational domains or preferences, as well as on prior research on personality and other aspects of motivation. Using this approach, we developed the following specic hypotheses. First, given that Neuroticism is characterized by emotional distress and poor impulse control, we expected students high in Neuroticism to have diculty in coping with academic challenges and dealing with setbacks (cf. Elliot & McGregor, 1999). Thus, we predicted that Neuroticism would be positively related with the AMI motives of debilitating anxiety, withdrawing, disliking school, and discouraged about school. Second, extraverted individuals are warm, socially-oriented, and assertive. Similarly, agreeable individuals tend to be trusting and cooperative, and may be receptive to collaborative

M. Komarraju, S.J. Karau / Personality and Individual Dierences 39 (2005) 557567

561

learning (De Raad & Shouwenburg, 1996). Therefore, we predicted that Extraversion and Agreeableness would both be positively related with approval and aliating motives. Because assertiveness is an element of Extraversion (Costa & McCrae, 1992), we also predicted that Extraversion would be related with inuencing motives. Third, given that individuals high in Openness seek novel experiences, are intellectually curious, and may be more receptive to novel educational experiences (Lounsbury et al., 2003), we predicted that Openness would be positively related with thinking and desire for self-improvement. Finally, conscientious individuals are generally organized, disciplined, and hard working, and have been found to achieve greater academic success (Busato et al., 2000). Hence, we predicted that Conscientiousness would be positively related with persisting, achieving, and desire for self-improvement. Conscientiousness may also be positively related with demanding or facilitating anxiety motives. Neither our relative t logic nor the prior literature provides the basis for clear predictions regarding economic or grades orientation motives.

2. Method One hundred and seventy two undergraduates (85 men and 87 women, primarily psychology or business majors), were asked to complete questionnaires containing the Five Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI, Costa & McCrae, 1992), the Academic Motivations Inventory (AMI, Moen & Doyle, 1977), and demographic information. The 60-item NEO-FFI measures ve personality traits. Neuroticism refers to emotional stability, impulse control, and ability to cope with stress. Extraversion refers to sociability, assertiveness, and talkativeness. Openness involves intellectual curiosity and preferring variety. Agreeableness involves being sympathetic, helpful, trusting, and cooperative. Conscientiousness refers to being organized, purposeful, and self-controlled. The

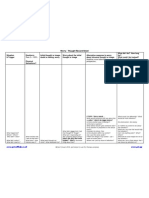

Table 1 Brief descriptions and coecient alphas for AMI subscales Motive (brief description) Thinking (enjoys thinking, analyzing) Persisting (tends to keep working until done) Achieving (enjoys hard work and doing well) Facilitating anxiety (anxiety that helps learning) Debilitating anxiety (anxiety that interferes with learning) Grades orientation (desires good grades) Economic orientation (focuses on career development) Desire for self-improvement (desire to increase competence) Demanding (wants good teaching) Inuencing (enjoys arguing with and inuencing others) Competing (wants to do better than others) Approval (seeks to do well to get praise from others) Aliating (enjoys being with others in school) Withdrawing (prefers to work alone) Disliking school (lack of interest in school) Discouraged about school (feels school is too hard) No. of items 9 3 5 3 5 7 4 6 5 4 3 9 4 6 4 7 Alphas .76 .68 .88 .54 .72 .78 .55 .68 .53 .63 .66 .82 .45 .69 .77 .71

562

M. Komarraju, S.J. Karau / Personality and Individual Dierences 39 (2005) 557567

NEO-FFI is the most widely used measure of personality traits, and has good reliability, internal consistency, and validity (Costa & McCrae, 1992). The Cronbach alpha values for the present study were 0.83 (Neuroticism), 0.65 (Extraversion), 0.66 (Openness), 0.66 (Agreeableness), and 0.82 (Conscientiousness). The 90-item AMI assesses individual dierences in 16 academic motivations. Prior research indicates that the AMI has acceptable reliabilities on almost all the scales for research purposes (Doyle & Moen, 1978), and oers evidence of concurrent validity against similar instruments and academic performance (Church & Katigbak, 1992; Church, Moen, & Doyle, 1985; Doyle & Moen, 1978; Moen & Doyle, 1977). Table 1 provides a brief description and current-study alpha values for each subscale.

3. Results 3.1. Correlation analysis Correlation analyses revealed a number of signicant relationships between Big Five traits and the 16 AMI subscales, consistent with predictions (see Table 2). Specically, conscientiousness was positively related with thinking, persisting, achieving, grades orientation, inuencing, and aliating motives, and was negatively related with debilitating anxiety, disliking school, and feeling discouraged. Similarly, openness to experience was positively related with thinking, persisting, achieving, desire for self-improvement, inuencing, and aliating, and was negatively related

Table 2 Correlations between big ve dimensions and subscales of the AMI AMI subscale Thinking Persisting Achieving Facilitating Anxiety Debilitating Anxiety Grades Orientation Economic Orientation Self-Improvement Demanding Inuencing Competing Approval Aliating Withdrawing Dislike School Discouraged Neuroticism .11 .13 .10 .15* .48** .19* .22** .01 .15 .16* .05 .22** .05 .41** .15 .46** Extraversion .14 .27** .07 .17* .02 .16* .21** .23** .09 .31** .08 .12 .40** .22** .12 .01 Openness to experience .45** .19* .21** .11 .03 .11 .18* .40** .02 .28** .03 .09 .26** .31** .17* .17* Agreeableness .05 .17* .10 .05 .06 .19* .08 .23** .02 .08 .19* .10 .16* .02 .08 .11 Conscientiousness .22** .60** .56** .15 .18* .36** .10 .09 .01 .21** .15 .01 .17* .10 .57** .35**

Note. N ranges from 167 to 172. * p < .05. ** p < .01.

M. Komarraju, S.J. Karau / Personality and Individual Dierences 39 (2005) 557567

563

with economic orientation, withdrawing, disliking school, and feeling discouraged. Neuroticism was positively associated with debilitating anxiety, economic orientation, approval, and withdrawing from school, and was negatively associated with facilitating anxiety and inuencing. Extraversion was positively related with persisting, facilitating anxiety, grades orientation, economic orientation, desire for self-improvement, inuencing, and aliating, and was negatively related with withdrawing. Finally, agreeableness was positively related with persisting, grades orientation, desire for self-improvement, and aliating, and was negatively related with competing. 3.2. Factor analysis To pursue a more parsimonious understanding of the complex pattern of signicant correlations, we conducted a principal components factor analysis of the sixteen subscales of the AMI. Three factors emerged (with eigenvalues of 4.94, 2.79, and 1.71), explaining 59% of the variance. The resulting subscales were labeled avoidance (six subscales, a = .75), engagement (six subscales a = .79), and achievement (four subscales, a = .80). Avoidance incorporates the subscales of debilitating anxiety, economic orientation, demanding, withdrawing, disliking school, and discouraged about school. Engagement includes the subscales of thinking, facilitating anxiety, desires self-improvement, inuencing, approval, and aliating. Finally, achievement consists of the subscales of persisting, achieving, grades orientation, and competing. 3.3. Regression analyses To help identify which elements of the Big Five traits were most strongly related with each of our three motivation factors, we conducted forward multiple regressions. We used the Big Five traits as well as gender and race as predictors, and treated each of the three academic motivation factors as dependent variables. This was done so that the predictors with the most explanatory power would be included rst in the model. The signicant predictors from each regression model are shown in Table 3. Neither gender nor race had any signicant inuence on these results.

Table 3 Forward multiple regression results with big ve dimensions regressed on academic motivation factors Factor Avoidance Step 1 2 3 4 1 2 1 2 3 Predictor Neuroticism Extraversion Conscientiousness Openness Openness Extraversion Conscientiousness Neuroticism Openness Beta .42** .20** .17** .15* .34** .32** .60** .22** .15* R2 .21 .24 .27 .29 .13 .23 .29 .32 .34 Change in R2 .21 .03 .03 .02 .13 .10 .29 .03 .02

Engagement Achievement

* **

p < .05. p < .01.

564

M. Komarraju, S.J. Karau / Personality and Individual Dierences 39 (2005) 557567

For avoidance, 29% of the variance was explained by four personality traits (Neuroticism, Extraversion, Conscientiousness, and Openness), F(4, 166) = 16.6, p < .001, adjusted R2 = .27. Neuroticism and Extraversion were positively related with avoidance, whereas Conscientiousness and Openness were negatively related with avoidance. Neuroticism was the strongest predictor, explaining 21% of the variance in avoidance. For engagement, 23% of the variance was explained by two personality traits (Openness and Extraversion), F(2, 168) = 25.3, p < .001, adjusted R2 = .22. Openness was the strongest predictor, explaining 13% of the variance in engagement. For achievement, 34% of the variance was explained by three personality traits (Conscientiousness, Neuroticism and Openness), F(3, 167) = 29.23, p < .001, adjusted R2 = .33. Conscientiousness was the strongest predictor, explaining 29% of the variance in achievement.

4. Discussion Our results indicate that personality is strongly related to academic motivation. Our correlation analyses show that personality was signicantly related with a wide variety of academic motivations. Our factor analysis of the subscales on the AMI yielded three particularly strong underlying academic motives: Avoidance, engagement, and achievement. Avoidant students tend to feel discouraged about school, worry about failure, withdraw in the classroom, and take courses for extrinsic reasons. In contrast, engaged students enjoy the process of learning, seek knowledge for self-improvement, and enjoy sharing ideas. Lastly, achievement oriented students put in eort to excel and enjoy outperforming others. Interestingly, these three subscales are somewhat consistent with the factor structure of the other major scale used to assess academic motivation, the AMS (Vallerand et al., 1992), which has extrinsic, intrinsic, and amotivation as its three major factors. Our regression analyses further clarify the nature of the relationships between the Big Five traits and the three key underlying academic motives. First, avoidance was positively related with both Neuroticism and Extraversion, and was negatively related with both Conscientiousness and Openness, with Neuroticism explaining the most variance. These results may suggest that neurotic students tend to avoid many aspects of academic life and view education as a means to an end rather than an intrinsically fullling enterprise. Similarly, extraverts may be more concerned with social aspects of college life. In contrast, conscientious and open students are less likely to be avoidant in their motivation. Second, students with higher levels of Openness and Extraversion were more engaged in learning, with Openness explaining the most variance. This suggests that students who are sociable and enjoy exposure to new ideas are likely to be engaged in the educational experience and may benet from discussion and interactive learning. It is interesting that Extraversion was related with both engagement and avoidance, suggesting that sociability may lead students to be both more involved in the learning processes and more concerned with social and economic consequences of learning. Third, students who were more conscientious, neurotic, and open to experience scored higher on achievement with Conscientiousness explaining the most variance. These results suggest that students who are responsible and intellectually curious may be more achievement oriented,

M. Komarraju, S.J. Karau / Personality and Individual Dierences 39 (2005) 557567

565

hard-working, and competitive. It is interesting that neuroticism was related with achievement. Although future research is needed to clarify this relationship, it is possible that compulsive preparation due to anxiety about failure may play a role. Taken as a whole, our multiple regression results suggest that dierences in student motivation levels that are often readily apparent in the classroom may be related to basic personality dierences. Hence, teachers may be able to enhance student learning by matching course activities to the motivational preferences held by students with diering personalities. Along with prior research showing that personality is related with more general aspects of learning (e.g., Zhang, 2003), our results about academic motivation suggest that general personality traits are strongly related with learning styles, preferences, and motivation. One clear implication of our ndings is that educators need to be aware that students are not homogenous in their levels of academic motivation or in their personalities. Therefore, it makes sense to match delivery modes and activities to the likely preferences of students. However, this could be dicult, especially in large classes. One option for teachers is to employ a variety of techniques and activities to increase the chances that they are reaching all students at least some of the time. For example, instructors who rely mostly on traditional lectures could supplement their courses with discussion, team activities, and experiential exercises. Teachers who are able to develop a wide repertoire of techniques are more likely to engage a larger number of students. Our results also suggest that educators who nurture the qualities of Openness and Conscientiousness may be able to increase the engagement and achievement levels of their students. This could be done by rewarding students for thinking beyond the connes of the topic and also making linkages to other elds. For example, students could be given assignments that focus on broad exposure and integration of ideas. Students could also be rewarded for showing conscientious behavior such as being organized and self-disciplined. The curriculum might also emphasize the importance of these qualities for success. Instructors could also employ clear norms and expectations early in the course that creative thought and high eort levels are valued. Training programs for new instructors could also emphasize the importance of individual dierences among students and the use of multiple teaching modalities. Our research also contributes valuable information about the factor structure of the AMI. The instrument was designed to measure 16 distinct subcomponents of overall academic motivation. However, the internal consistency for some subscales is low or marginal, and researchers may not be interested in examining all 16 components for some projects. Our factor analytic results show that these subscales can be subsumed into three organizing factors that appear to represent avoidance, engagement, and achievement. Moreover, each of these three factors has good internal consistency. Our analysis of the relationship between these three key factors and personality further suggests that they represent distinct aspects of academic motivation. Hence, researchers might consider using this three-factor version of the AMI in future research, especially for projects where the distinction between avoidance, engagement, and achievement is likely to play a central role. Readers should keep in mind that this study does have limitations that might be addressed in future research. First, additional individual dierence variables such as learning styles, thinking styles, or ability measures could be examined in relation to academic motivation. Second, other measures of academic motivation could be employed. Although the AMI (Moen & Doyle, 1977) has the benets of examining many aspects of academic motivation, the AMS (Vallerand

566

M. Komarraju, S.J. Karau / Personality and Individual Dierences 39 (2005) 557567

et al., 1992) is a briefer measure with good psychometric properties that may reect a somewhat dierent motivational landscape. Convergence of results across both measures, would add to our condence in drawing more specic conclusions for teachers. Finally, a wider variety of samples could be studied that dier in features such as culture, location, and type or size of school. Until additional research on these issues has been conducted, the current results must be considered somewhat tentative. However, the current study takes the important rst step of documenting that fundamental aspects of personality are strongly related to distinct aspects of academic motivation. We hope that this research stimulates additional exploration of the relationships between personality and academic motivation. References

Abouserie, R. (1995). Self-esteem and achievement motivation as determinants of students approaches to studying. Studies in Higher Education, 20, 1926. Ackerman, P. L., & Heggestad, E. D. (1997). Intelligence, personality, and interests: Evidence for overlapping traits. Psychological Bulletin, 121, 219245. Biggs, J. B. (1993). What do inventories of students learning processes really measure? A theoretical review and clarication. British Journal of Psychology, 63, 319. Busato, V. V., Prins, F. J., Elshout, J. J., & Hamaker, C. (1999). The relation between learning styles, the big ve personality traits, and achievement motivation in higher education. Personality and Individual Dierences, 26, 129140. Busato, V. V., Prins, F. J., Elshout, J. J., & Hamaker, C. (2000). Intellectual ability, learning style, personality, achievement motivation and academic success of psychology students in higher education. Personality and Individual Dierences, 29, 10571068. Chamorro-Premuzic, T., & Furnham, A. (2003). Personality traits and academic examination performance. European Journal of Personality, 17, 237250. Church, A. T., & Katigbak, M. S. (1992). The cultural context of academic motives: A comparison of Filipino and American college students. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 23, 4058. Church, A. T., Moen, R., & Doyle, K. O., Jr. (1985). Toward clarication of the structure and dynamics of academic motivations as measured by the Academic Motivation Inventory (AMI). University of Minnesota, Measurement Services Center, Minneapolis, MN, unpublished manuscript. Costa, P. T., & McCrae, R. R. (1992). NEO PI-R: Professional manual: Revised NEO PI-R and NEO-FFI. Florida: Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc. Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. New York: Plenum Press. De Raad, B., & Shouwenburg, H. C. (1996). Personality in learning and education. European Journal of Personality, 10, 303336. Doyle, K. O., Jr., & Moen, R. (1978). Toward the denition of the domain of academic motivation. Journal of Educational Psychology, 70(2), 231236. Dweck, C. S., & Leggett, E. L. (1988). A social-cognitive approach to motivation and personality. Psychological Review, 95, 256273. Elliot, A. J., & McGregor, H. A. (1999). Test anxiety and the hierarchical model of approach and avoidance achievement motivation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 76, 628644. Entwistle, N. J., & Entwistle, D. (1970). The relationships between personality, study methods, and academic performance. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 40, 132143. Farsides, T., & Woodeld, R. (2003). Individual dierences and undergraduate academic success: The roles of personality, intelligence, and application. Personality and Individual Dierences, 33, 12251243. Furnham, A. (1992). Personality and learning style: A study of three instruments. Personality and Individual Dierences, 13, 429438.

M. Komarraju, S.J. Karau / Personality and Individual Dierences 39 (2005) 557567

567

Furnham, A., & Medhurst, S. (1995). Personality correlates of academic seminar behavior: A study of four instruments. Personality and Individual Dierences, 19, 197208. Furnham, A., & Mitchell, J. (1991). Personality, needs, social skills and academic achievement: A longitudinal study. Personality and Individual Dierences, 12, 10671073. Gardner, H. (1983). Frames of mind: The theory of multiple intelligences. New York: Basic Books. Heaven, P. L. (1989). Attitudinal and personality correlates of achievement motivation among high school students. Personality and Individual Dierences, 11, 705710. Heaven, P. L., Mak, A., Barry, J., & Ciarrochi, J. (2002). Personality and family inuences on adolescent attitudes to school and self-rated academic performance. Personality and Individual Dierences, 32, 453462. Kanfer, R., Ackerman, P. L., & Heggestad, E. D. (1996). Motivational skills and self-regulation for learning: A trait perspective. Learning and Individual Dierences, 8, 185204. Linnenbrink, E. A., & Pintrich, P. R. (2002). Motivation as an enabler for academic success. The School Psychology Review, 31, 313327. Livengood, J. L. (1992). Students motivational goals and beliefs about eort and ability as they relate to college academic success. Research in Higher Education, 33, 247261. Lounsbury, J. W., Sundstrom, E., Loveland, J. M., & Gibson, L. W. (2003). Intelligence, Big Five personality traits, and work drive as predictors of course grade. Personality and Individual Dierences, 35, 12311239. Moen, R., & Doyle, K. O., Jr. (1977). Construction and development of the academic motivations inventory (AMI). Educational and Psychological Measurement, 37, 509512. Pritchard, M. E., & Wilson, G. S. (2003). Using emotional and social factors to predict student success. Journal of College Student Development, 44, 1828. Riding, R. J., & Wigley, S. (1997). The relationship between cognitive style and personality in further education students. Personality and Individual Dierences, 23, 379389. Rothstein, M. G., Paunonen, S. V., Rush, J. C., & King, G. A. (1994). Personality and cognitive ability predictors of performance in graduate business school. Journal of Educational Psychology, 86, 516530. Schmeck, R., & Geisler Brenstein, E. (1991). Self-concept and learning: The revised-inventory of learning processes. Educational Psychology, 11, 343363. Sternberg, R. J., Tor, B., & Grigorenko, E. L. (1998). Teaching triarchically improves school achievement. Journal of Educational Psychology, 90, 374384. Stipek, D. (2002). Motivation to learn: Integrating theory and practice. Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon. Vallerand, R. J., Pelletier, L. G., Blais, M. R., Briere, N. M., Senecal, C., & Vallieres, E. F. (1992). The academic motivation scale: A measure of intrinsic, extrinsic, and amotivation in education. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 52, 10031017. Vermetten, Y. J., Lodewijks, H. G., & Vermunt, J. D. (2001). The role of personality traits and goal orientations in strategy use. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 26, 149170. Wolfe, R. N., & Johnson, S. D. (1995). Personality as a predictor of college performance. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 55, 177185. Zhang, L. (2002). Measuring thinking styles in addition to personality traits? Personality and Individual Dierences, 33, 445458. Zhang, L. (2003). Does the big ve predict learning approaches? Personality and Individual Dierences, 34, 14311446.

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- Relationship Between MBTI and Career Success - Yu 2011Dokumen6 halamanRelationship Between MBTI and Career Success - Yu 2011alanwilBelum ada peringkat

- The Trait Approach To Personality Is One of The Major Theoretical Areas in The Study of PersonalityDokumen17 halamanThe Trait Approach To Personality Is One of The Major Theoretical Areas in The Study of PersonalityClaire RoxasBelum ada peringkat

- MBTI Types and Executive Coaching 2006Dokumen9 halamanMBTI Types and Executive Coaching 2006Nilesh WarBelum ada peringkat

- StartingDokumen2 halamanStartingMuhammad Yusuf PilliangBelum ada peringkat

- DWYA Counselor HandbookDokumen23 halamanDWYA Counselor HandbookNafizAlamBelum ada peringkat

- Still Believe in The MBTI Personality Type Theory? Think AgainDokumen3 halamanStill Believe in The MBTI Personality Type Theory? Think AgainJennifer WilsonBelum ada peringkat

- Stress Management For Every Type: Carol Sommerfield, PH.D., PMP, SPHR, GCDFDokumen26 halamanStress Management For Every Type: Carol Sommerfield, PH.D., PMP, SPHR, GCDFsddsppBelum ada peringkat

- Article - Big Five Factor Model, Theory and StructureDokumen10 halamanArticle - Big Five Factor Model, Theory and StructureMaria RudiukBelum ada peringkat

- TypologyDokumen4 halamanTypologyNuur LanaBelum ada peringkat

- Toward A New Approach To The Sutyd of Personality in CultureDokumen11 halamanToward A New Approach To The Sutyd of Personality in Culturewyh1919100% (1)

- Nature, Goals, Definition and Scope of PsychologyDokumen9 halamanNature, Goals, Definition and Scope of PsychologyNikhil MaripiBelum ada peringkat

- Creativity: Creativity Is A Process Involving The Generation of New Ideas or Concepts, orDokumen13 halamanCreativity: Creativity Is A Process Involving The Generation of New Ideas or Concepts, orhghjjjBelum ada peringkat

- Ecofeminism Thoughts: The Effective Analysis Based On Mother ArchetypeDokumen6 halamanEcofeminism Thoughts: The Effective Analysis Based On Mother ArchetypereviewjreBelum ada peringkat

- Do What You Are Handbook 2008Dokumen23 halamanDo What You Are Handbook 2008q12345q6789Belum ada peringkat

- A Dialogue of Unconsciouses PDFDokumen10 halamanA Dialogue of Unconsciouses PDFIosifIonelBelum ada peringkat

- Guilford Structure of Intellect ModelDokumen2 halamanGuilford Structure of Intellect ModelIkram KhanBelum ada peringkat

- HOWARD Pierce The Big Five Quickstart PDFDokumen27 halamanHOWARD Pierce The Big Five Quickstart PDFCarlos VenturoBelum ada peringkat

- Excellence Success: Understand Yourself Using MBTIDokumen3 halamanExcellence Success: Understand Yourself Using MBTIMuhammad Qamarul HassanBelum ada peringkat

- Ocs DmsDokumen12 halamanOcs Dmsrhea dhirBelum ada peringkat

- Historical Developments of Social PsychologyDokumen2 halamanHistorical Developments of Social PsychologyAnjali Manu100% (1)

- Theories of MotivationDokumen19 halamanTheories of MotivationvaibhavBelum ada peringkat

- NEO PI SummaryDokumen12 halamanNEO PI Summaryanitnerol0% (1)

- Detection of Myers-Briggs Type Indicator Via Text Based Computer-Mediated CommunicationDokumen4 halamanDetection of Myers-Briggs Type Indicator Via Text Based Computer-Mediated CommunicationanilaisuigresBelum ada peringkat

- Eysenck Personality To CommunicateDokumen48 halamanEysenck Personality To CommunicateYenni RoeshintaBelum ada peringkat

- You Want To Measure Coping But Your Protocol's Too Long: Consider The Brief COPEDokumen9 halamanYou Want To Measure Coping But Your Protocol's Too Long: Consider The Brief COPEGon MartBelum ada peringkat

- Basic Concepts of The SelfDokumen4 halamanBasic Concepts of The SelfMargaret Joy SobredillaBelum ada peringkat

- Flow The Psychology of Optimal ExperienceDokumen6 halamanFlow The Psychology of Optimal ExperienceJdalliXBelum ada peringkat

- Abpc1203 Psychological Tests and MeasurementsDokumen14 halamanAbpc1203 Psychological Tests and MeasurementsSiva100% (1)

- Meanning and Nature of SelfDokumen5 halamanMeanning and Nature of SelfJaqueline Benj OftanaBelum ada peringkat

- Mbti-Presentation Phone InterpretationDokumen17 halamanMbti-Presentation Phone Interpretationapi-339838665Belum ada peringkat

- Attribution TheoryDokumen4 halamanAttribution TheoryShanmuga VadivuBelum ada peringkat

- TAT (Thematic Apperception Test)Dokumen36 halamanTAT (Thematic Apperception Test)ChannambikaBelum ada peringkat

- Chapter 8 Motivation and EmotionDokumen5 halamanChapter 8 Motivation and EmotionMaricris GatdulaBelum ada peringkat

- DR Garima Rogers Theory of PersonalityDokumen19 halamanDR Garima Rogers Theory of PersonalitySatchit MandalBelum ada peringkat

- Academic OptimismDokumen23 halamanAcademic OptimismJay Roth100% (1)

- UNIT 2 Research Method in Psychology IGNOU BADokumen15 halamanUNIT 2 Research Method in Psychology IGNOU BAashish1981Belum ada peringkat

- 4.1 Social InteractionDokumen20 halaman4.1 Social Interactionsabahat saeed100% (1)

- Big 5 FactorDokumen12 halamanBig 5 FactoryashBelum ada peringkat

- Theories F PersonalityDokumen6 halamanTheories F Personalitykay100% (1)

- Gergen and Gergen, Narratives of The Self, 1997 PDFDokumen13 halamanGergen and Gergen, Narratives of The Self, 1997 PDFAlejandro Hugo GonzalezBelum ada peringkat

- HOPE Scales (A Few)Dokumen9 halamanHOPE Scales (A Few)Mike F MartelliBelum ada peringkat

- Constructivist and Narrative Approaches To Career DevelopmentDokumen13 halamanConstructivist and Narrative Approaches To Career Developmentemanuel morales100% (1)

- Holism & Reductionism: Issues and DebatesDokumen30 halamanHolism & Reductionism: Issues and Debatesh100% (1)

- Behavior and Attitudes: Components of Attitude or The Abc of AttitudeDokumen2 halamanBehavior and Attitudes: Components of Attitude or The Abc of AttitudeJeri-Mei CadizBelum ada peringkat

- The in Uence of Superhero Comic Books On Adult Altruism: December 2016Dokumen25 halamanThe in Uence of Superhero Comic Books On Adult Altruism: December 2016Claudio SanhuezaBelum ada peringkat

- 6 Thesis With Revisions PDFDokumen88 halaman6 Thesis With Revisions PDFApple GonzalesBelum ada peringkat

- Tennessee Self-Concept ScaleDokumen9 halamanTennessee Self-Concept ScaleJosé SantosBelum ada peringkat

- Notes On MurrayDokumen8 halamanNotes On MurrayBenjamin Co100% (2)

- Five Factors of PersonalityDokumen12 halamanFive Factors of PersonalityCristina M. PascariBelum ada peringkat

- Lecture 1 Experimental Psychology (Psychophysics)Dokumen10 halamanLecture 1 Experimental Psychology (Psychophysics)sumaira_m89Belum ada peringkat

- Course Information Uts Converted Converted 1Dokumen7 halamanCourse Information Uts Converted Converted 1Jhunuarae AlonzoBelum ada peringkat

- Statistics-: Data Is A Collection of FactsDokumen3 halamanStatistics-: Data Is A Collection of FactsLonnieAllenVirtudesBelum ada peringkat

- Personality Theory PaperDokumen6 halamanPersonality Theory PaperSundra Flash Fab BlingBelum ada peringkat

- Workplace Emotions and AttitudesDokumen27 halamanWorkplace Emotions and AttitudesDr Rushen SinghBelum ada peringkat

- Development of The Emotional Intelligence Scale PDFDokumen13 halamanDevelopment of The Emotional Intelligence Scale PDFFrancisco MuñozBelum ada peringkat

- Perspectives in Modern PsychologyDokumen10 halamanPerspectives in Modern PsychologyCaissa PenaBelum ada peringkat

- Humanistic Perspectives On Personality - Boundless PsychologyDokumen11 halamanHumanistic Perspectives On Personality - Boundless PsychologySubhas RoyBelum ada peringkat

- To What Extent Can The Big Five and Learning Styles Predict Academic AchievementDokumen9 halamanTo What Extent Can The Big Five and Learning Styles Predict Academic AchievementJeremyBelum ada peringkat

- Final Siop Lesson Plan 2Dokumen11 halamanFinal Siop Lesson Plan 2api-242470619Belum ada peringkat

- Motivation and Performance: Prof. Sidra Lecture#5Dokumen19 halamanMotivation and Performance: Prof. Sidra Lecture#5azamtoorBelum ada peringkat

- Person-Job Fit or Person-Organisation FitDokumen2 halamanPerson-Job Fit or Person-Organisation FitssimukBelum ada peringkat

- Endler I Kocovski 2001Dokumen15 halamanEndler I Kocovski 2001Bojana DjuricBelum ada peringkat

- A 90 Minutes' Sample Lesson Plans On The Method Multiiple IntelligencesDokumen3 halamanA 90 Minutes' Sample Lesson Plans On The Method Multiiple IntelligencesOmar MunnaBelum ada peringkat

- My Reflection About SelfDokumen1 halamanMy Reflection About SelfBernie OrtegaBelum ada peringkat

- Edfd 116 1st Sem 2012 WITH DATESDokumen4 halamanEdfd 116 1st Sem 2012 WITH DATESLikhaan PerformingArts HomeStudioBelum ada peringkat

- Tasjunique Graham Final PaperDokumen2 halamanTasjunique Graham Final Paperapi-238334599Belum ada peringkat

- Read and Retell 3 Students BookDokumen83 halamanRead and Retell 3 Students BookEkaterina Rybakova100% (2)

- Assessing 21st Century SkillsDokumen1 halamanAssessing 21st Century Skillsapi-227888640Belum ada peringkat

- Lesson Plan - Quarter Note RestDokumen4 halamanLesson Plan - Quarter Note Restapi-262606032100% (2)

- Scared YouthDokumen2 halamanScared Youthnarcis2009Belum ada peringkat

- Student Learning Outcomes Self Assessment ErwcDokumen2 halamanStudent Learning Outcomes Self Assessment Erwcapi-359540365Belum ada peringkat

- 10) Performance Management and FeedbackDokumen17 halaman10) Performance Management and FeedbackDanna ClaireBelum ada peringkat

- Let's Read and Answer. (Textbook Page: 44) : Rancangan Pengajaran HarianDokumen4 halamanLet's Read and Answer. (Textbook Page: 44) : Rancangan Pengajaran HarianElisha PaulBelum ada peringkat

- Jquap - Clinical Field Experience B Aligning LessonsDokumen7 halamanJquap - Clinical Field Experience B Aligning Lessonsapi-524975964Belum ada peringkat

- Review For LET Values Education Part 3Dokumen2 halamanReview For LET Values Education Part 3jenalynBelum ada peringkat

- Assignment 2Dokumen2 halamanAssignment 2Aishwarrya NanthakumarBelum ada peringkat

- EDUC 101 Facilitating LearningDokumen10 halamanEDUC 101 Facilitating LearningLeidi Kyohei NakaharaBelum ada peringkat

- How To Diagnose Mixed Features Without Overdiagnosing BipolarDokumen4 halamanHow To Diagnose Mixed Features Without Overdiagnosing Bipolardo leeBelum ada peringkat

- Yyyyy Yyy Yy Yyyy Y Yyy Yyy Yyyyyyy Yy YyyyyyyyDokumen6 halamanYyyyy Yyy Yy Yyyy Y Yyy Yyy Yyyyyyy Yy YyyyyyyyRasika JadhavBelum ada peringkat

- Lesson Plan Template Letter PDokumen3 halamanLesson Plan Template Letter Papi-296883339Belum ada peringkat

- GAD Thought Record SheetDokumen1 halamanGAD Thought Record SheetpanickedchickBelum ada peringkat

- Reflection of Psychology 1010Dokumen2 halamanReflection of Psychology 1010api-270635734Belum ada peringkat

- PA 214 Case Study No 3Dokumen2 halamanPA 214 Case Study No 3Hazel Mae JumaaniBelum ada peringkat

- Action Plan in EnglishDokumen3 halamanAction Plan in EnglishBrylleEscrandaEstradaBelum ada peringkat

- Detailed Lesson Plan (DLP) : Nature and Elements of CommunicationDokumen2 halamanDetailed Lesson Plan (DLP) : Nature and Elements of CommunicationJesslyn Mar GenonBelum ada peringkat

- Assessment Rubric Task 1Dokumen1 halamanAssessment Rubric Task 1api-233572018Belum ada peringkat

- Department of Education: Republic of The PhilippinesDokumen3 halamanDepartment of Education: Republic of The PhilippinesAlvin Echano AsanzaBelum ada peringkat