Barrett's Esophagus

Diunggah oleh

Si vis pacem...Deskripsi Asli:

Judul Asli

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Barrett's Esophagus

Diunggah oleh

Si vis pacem...Hak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

COVER ARTICLE

Barretts Esophagus

MARK D. SHALAUTA, M.D., University of California, San Diego, School of Medicine, San Diego, California RICHARD SAAD, M.D., University of Michigan Medical School, Ann Arbor, Michigan Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is a condition commonly managed in the primary care setting. Patients with GERD may develop reflux esophagitis as the esophagus repeatedly is exposed to acidic gastric contents. Over time, untreated reflux esophagitis may lead to chronic complications such as esophageal stricture or the development of Barretts esophagus. Barretts esophagus is a premalignant metaplastic process that typically involves the distal esophagus. Its presence is suspected by endoscopic evaluation of the esophagus, but the diagnosis is confirmed by histologic analysis of endoscopically biopsied tissue. Risk factors for Barretts esophagus include GERD, white or Hispanic race, male sex, advancing age, smoking, and obesity. Although Barretts esophagus rarely progresses to adenocarcinoma, optimal management is a matter of debate. Current treatment guidelines include relieving GERD symptoms with medical or surgical measures (similar to the treatment of GERD that is not associated with Barretts esophagus) and surveillance endoscopy. Guidelines for surveillance endoscopy have been published; however, no studies have verified that any specific treatment or management strategy has decreased the rate of mortality from adenocarcinoma. (Am Fam Physician 2004;69: 2113-8,2120. Copyright 2004 American Academy of Family Physicians.)

mation handout on Barretts esophagus, written by the authors of this article, is provided on page 2120.

O A patient infor-

arretts esophagus was first described in 1950 by Norman Barrett, who reported a case of chronic peptic ulcer in the lower esophagus that was covered by epithelium.1 Barretts esophagus can be defined simply as columnar metaplasia of the esophagus. Patients who have columnar epithelium that measures 3 cm or more from the gastroesophageal junction are said to have traditional, or long-segment, Barretts esophagus, while patients with a measure less than 3 cm have short-segment Barretts esophagus.2 In 1998, the American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) defined Barretts esophagus as a change in the esophageal epithelium of any length that can be recognized at endoscopy and is confirmed to have intestinal metaplasia by biopsy of the tubular esophagus and excludes intestinal metaplasia of the cardia.3 Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD)

See editorials on pages 2060 and 2061.

See page 2043 for definitions of strength-ofrecommendation labels.

is a condition commonly evaluated and managed in the primary care setting. Surveys suggest that approximately 20 percent of U.S. adults have symptoms of GERD at least once a week.4 A subgroup of patients with GERD develop severe complications that include erosive esophagitis, stricture formation, Barretts esophagus, and adenocarcinoma of the esophagus. Because Barretts esophagus is thought to be associated with the development of adenocarcinoma, it is imperative that primary care physicians be familiar with Barretts esophagus, its association with GERD, and its diagnosis and management. The overall prevalence of Barretts esophagus in the general population is difficult to estimate, because approximately 25 percent of persons with Barretts esophagus have no symptoms of reflux.5 It is known, however, that the incidence of adenocarcinoma of the esophagus has risen sharply in the past few decades. The results of one study6 note that the incidence of adenocarcinoma in white men has increased by more than 350 percent since the mid-1970s. Identification of patients at risk for adenocarcinoma of the

Downloaded from the American Family Physician Web site at www.aafp.org/afp. Copyright 2004 American Academy of Family Physicians. For the private, noncommercial use of one individual user of the Web site. All other rights reserved. Contact copyrights@aafp.org for copyright questions and/or permission requests.

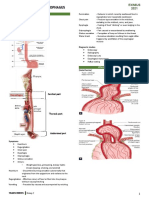

Progression of Squamous Epithelium

Normal epithelium Esophagitis Metaplasia/Barretts esophagus

esophagus is fairly poor. In fact, only 5 percent of patients who had resection of esophageal adenocarcinoma were known to have Barretts esophagus before the resection, highlighting the fact that current screening techniques are relatively ineffective.7 Perhaps by increasing awareness of Barretts esophagus, we can better target screening of high-risk patients. Pathophysiology and Diagnosis Progression from GERD to adenocarcinoma is thought to follow a stepwise process. It is believed that exposure of the esophageal epithelium to acid damages the lining, causing chronic esophagitis. The damaged area then heals in a metaplastic process in which abnormal columnar cells replace squamous cells. This abnormal intestinal columnar epithelium, which is called specialized intestinal metaplasia, can then progress to dysplasia, ultimately leading to carcinoma8 (Figure 1). The incidence of Barretts esophagus progressing to adenocarcinoma is estimated to be 0.5 per 100 patient-years (i.e., one in 200 patients developing carcinoma per year).9 Barretts esophagus is diagnosed by endoscopy and histology. The line at which the columnar epithelium transitions to the squamous epithelium (i.e., the squamocolumnar junction) is known as the Z-line. Normally, the Z-line corresponds to the The Authors

MARK D. SHALAUTA, M.D., is assistant clinical professor in the Department of Family and Preventive Medicine at the University of California, San Diego, School of Medicine. He received his medical degree from George Washington University School of Medicine and Health Sciences in Washington, D.C., and completed a residency in family practice at Kaiser Permanente in Woodland Hills, Calif. RICHARD SAAD, M.D., is a fellow in the Division of Gastroenterology, Department of Internal Medicine, at the University of Michigan Medical School, Ann Arbor. He received his medical degree from Jefferson Medical College of Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, and completed a residency in internal medicine at Brooke Army Medical Center in San Antonio. Dr. Saad was a general internist in the U.S. Army for four years before beginning his fellowship. Address correspondence to Mark D. Shalauta, M.D., UCSDScripps Ranch, 9909 Mira Mesa Blvd., Suite 200, San Diego, CA 92131 (e-mail: mshalauta@ucsd.edu). Reprints are not available from the authors.

Low-grade dysplasia High-grade dysplasia Adenocarcinoma

FIGURE 1. Progression of squamous epithelium to adenocarcinoma of the esophagus.

gastroesophageal junction. In patients with Barretts esophagus, the columnar epithelium extends proximally up the esophagus (Figure 2). As mentioned previously, long-segment Barretts esophagus measures 3 cm or more from the gastroesophageal junction, while short-segment Barretts esophagus is less than 3 cm from the gastroesophageal junction. It is unknown whether the natural course or pathogenesis varies between these two entities or whether short-segment Barretts esophagus progresses to long-segment disease. It makes sense that more metaplasia would predispose to more cancer, and one study10 has shown this to be the case. However, current guidelines recommend managing longand short-segment Barretts esophagus in the same manner.3 Screening Given the high prevalence of GERD, it is physically and financially impossible to screen all patients with GERD symptoms for the development of Barretts metaplasia. Obviously, patients with alarm symptoms such as dysphagia, odynophagia, bleeding, or weight loss should be referred promptly for endoscopy. In patients without alarm symptoms, screening guidelines for Barretts esophagus are somewhat problematic. Symptoms of GERD are usually the reason a patient is referred for evaluation for Barretts esophagus but, as previously mentioned, many patients are asymptomatic.5 Currently, there is little evidence that screen-

2114-AMERICAN FAMILY PHYSICIAN

www.aafp.org/afp

VOLUME 69, NUMBER 9 / MAY 1, 2004

The American College of Gastroenterology states that patients with chronic symptoms of GERD are those most likely to have Barretts esophagus and should undergo upper endoscopy.

FIGURE 2. Barretts esophagus. Reddish, columnar epithelium extends above the gastroesophageal junction (long arrow). Squamocolumnar junction (Z-line) (short arrow).

ing for Barretts esophagus decreases the rate of mortality from adenocarcinoma.11 Several possible reasons for this finding include the older age of patients being studied and the relatively low absolute risk of adenocarcinoma of the esophagus. Current studies lack adequate power to show statistical significance. Nevertheless, the ACG states that patients with chronic GERD symptoms are those most likely to have Barretts esophagus and should undergo upper endoscopy.3 With this general guideline in mind, other elements of the risk assessment for Barretts esophagus and esophageal adenocarcinoma may be considered (Table 1). For instance, symptom severity alone is not an accurate marker; however, patients with a long history of reflux are at greater risk. Patients who had symptoms of GERD more than three times per week for more than 20 years have a 40-fold increased risk of developing adenocarcinoma.12 The incidence of Barretts esophagus is

TABLE 1

much higher in whites and Hispanics, compared with rates among blacks and Asians.13 Epidemiologic data also indicate that men are at greatest risk and, although Barretts esophagus can be found at any age, the prevalence increases with advancing age until a plateau is reached in the 60s.14 Other possible risk factors include tobacco use and obesity. Cigarette smoking, in particular, is associated with an approximately twofold increase in adenocarcinoma compared with the rate in nonsmokers, and this risk persists for years after smoking cessation.15,16 The question of whom to screen remains. One recent study17 suggests once-in-a-lifetime endoscopy screening in 50-year-old white men with GERD. In patients without dysplasia, even those with Barretts esophagus, further screening was not performed. This strategy appeared to be reasonable and cost-effective because the rate of conversion to adenocarcinoma is so low.17 A reasonable interpretation of the ACG recommendations might be to perform endoscopy in a patient with a combination of risk factorsalthough which risk factors will depend on clinical judgment and conversations with the patientas well as symptoms occurring three or more times per week for several years. Unfortunately, there will be many variations on these parameters until further information is available. Treatment Treatment of Barretts esophagus is aimed at decreasing reflux of acid into the esophagus. Although GERD is the primary risk factor for developing esophageal adenocarcinoma,5 it is unclear whether GERD predisposes patients to malignancy by causing Barretts esophagus or by affecting carcinogenesis in patients with established Barretts esophagus.18 Both medical and surgical therapies have proved effective in controlling symptoms.19 However, symptom control does not seem to correlate with complete acid control. A study20 of esophageal pH monitoring showed that symptom relief using conventional dosages of proton pump inhibiAMERICAN FAMILY PHYSICIAN-2115

Factors Associated with Barretts Esophagus and Adenocarcinoma

GERD, especially of long duration White or Hispanic race Male sex Advancing age (reaching a plateau in the 60s) Smoking Obesity

NOTE:

Listed from most to least clinically significant.

GERD = gastroesophageal reflux disease.

MAY 1, 2004 / VOLUME 69, NUMBER 9

www.aafp.org/afp

TABLE 2

ACG Surveillance Recommendations for Patients with Barretts Esophagus

Patients with Barretts esophagus should undergo surveillance endoscopy with biopsies. GERD should be treated before endoscopy to minimize inflammation, which can make interpretation more difficult. Patients with two consecutive negative surveillance endoscopies showing no dysplasia may undergo subsequent surveillance every three years. Patients with dysplasia should have the diagnosis confirmed by another expert pathologist. Patients with low-grade dysplasia should receive annual surveillance endoscopy. Patients with high-grade dysplasia can receive short-interval endoscopy (i.e., every three months) or intervention (e.g., esophagectomy), depending on the extent of the dysplasia. ACG = American College of Gastroenterology; GERD = gastroesophageal reflux disease. Information from reference 3.

tors (PPIs) does not necessarily correlate with suppression of acid reflux into the esophagus. Although aggressive medical treatment with PPIs and histamine H2 receptor antagonists to produce near-complete achlorhydria has been advocated, this approach remains controversial.2 The efficacy of surgical therapy in preventing adenocarcinoma also remains unclear. Recent evaluations of surgical therapy such as fundoplication showed no significant decrease in the risk of adenocarcinoma compared with medical therapy.21 Given the lack of adequate data to support more aggressive measures, the ACG recommends that, in patients with Barretts esophagus, GERD be managed in the same manner as in patients with GERD who do not have Barretts esophagus: the control of symptoms of GERD and the maintenance of healed mucosa.3 Antireflux therapy (medical or surgical) should not be prescribed beyond that needed for healing signs and symptoms of reflux esophagitis.3 Surveillance Once Barretts esophagus is discovered, the question of how to follow affected patients arises. Surveillance of Barretts esophagus is a relatively unproven area of study. As in screening, no evidence has shown that surveillance improves mortality rates.2,22,23 Proponents of surveillance endoscopy claim that previous studies included elderly patients who fre2116-AMERICAN FAMILY PHYSICIAN

quently died from unrelated causes, and that younger patients would likely benefit from surveillance.24 Others suggest that, given the low rate at which Barretts esophagus progresses to adenocarcinoma (0.5 percent per year), low-risk asymptomatic patients (i.e., Asians and blacks, women of any age), patients older than 75 years, and those with precarious health conditions do not need routine surveillance if the initial endoscopy showed no dysplasia.25 Published guidelines for the surveillance of Barretts esophagus suggest different intervals for surveillance endoscopy, depending on histologic findings of previous endoscopy.3 The ACG recommendations are summarized in Table 2.3 Recommendations for endoscopy every three years in patients without dysplasia were based on adenocarcinoma incidence rates of 1 to 2 percent per year. With more recent studies reporting the true incidence of 0.5 percent per year, a less frequent endoscopy interval of three to five years is also reasonable.2 As already mentioned, once-in-a-lifetime endoscopy may be sufficient in patients without dysplasia.17 The cost of surveillance has been analyzed. In the United Kingdom, it would cost an estimated $23,000 to detect one case of esophageal cancer in men, compared with $65,000 in women.26 A U.S. study27 estimated the cost for men and women to be approximately $38,000. To compare, detecting one case of breast cancer using mammography was estimated to cost about $55,000. It is important to note that the incidence rates used in these studies were higher than current estimates, so the cost of surveillance actually may be higher. There are several limitations to surveillance in patients with dysplasia. The histologic properties of dysplasia may be difficult to evaluate, because inflamed and healing epithelium may be similar in appearance. In addition, sampling errors (e.g., missed areas from random sampling) and lack of interobserver agreement of histologic specimens (especially in

www.aafp.org/afp

VOLUME 69, NUMBER 9 / MAY 1, 2004

Barretts Esophagus

low-grade dysplasia) make this process less than perfect. By the time high-grade dysplasia is noted, many of these patients already have invasive carcinoma.2 Future modalities include the use of other markers of cancer risk and different endoscopic techniques, such as employing cytology as an adjunct to biopsy, chromoendoscopy (i.e., use of vital dyes such as methylene blue), and spectroscopic biopsy techniques, which may improve the diagnostic accuracy of Barretts esophagus screening and surveillance.28 Approaches to high-grade dysplasia include esophagectomy or, possibly, surveillance, as noted in the ACG guidelines. Other societies recommend that all relatively healthy patients with high-grade dysplasia be considered for esophagectomy.2 Other options include endoscopic ablation with thermal or photodynamic therapy. Photodynamic therapy is a nonthermal means of ablating tissue, using visible light, a photosensitizer, and oxygen. The photosensitizer is absorbed preferentially by premalignant or malignant tissue, followed by light activation via laser. Photofrin (porfimer sodium) currently is the only agent approved in the United States.29 Limitations of ablative therapy include esophageal stricture and incomplete ablation of dysplastic tissue. Helicobacter pylori and Barretts Esophagus Helicobacter pylori infection tends to cause inflammation in the stomach, which may lead to gastric metaplasia and carcinoma; however, infection does not occur in the esophagus. Some data suggest that H. pylori infection actually decreases the risk of GERD, Barretts esophagus, and adenocarcinoma of the esophagus. One proposed mechanism is that chronic gastritis may interfere with acid production and increase gastric pH.30 Despite these associations, little is known about the relationship between H. pylori and GERD and its complications. Currently, guidelines do not recommend testing for or treating H. pylori infection in patients with GERD and its complications.31

A reasonable interpretation of the ACG recommendations for Barretts esophagus would be to perform endoscopy in patients with a combination of risk factors as well as symptoms occurring three or more times per week for several

Final Comment Barretts esophagus is an acquired condition that results from injury of the squamous epithelium of the esophagus through repetitive exposure to gastric acid. Although Barretts esophagus is associated with adenocarcinoma of the esophagus, no studies show a decrease in mortality from adenocarcinoma in the way the condition is managed currently. Nonetheless, management guidelines, which seem to make intuitive sense, do exist. It is important to closely monitor patients with GERD and to educate them to return for medical advice if symptoms persist despite treatment; endoscopy is indicated in these patients. Once a diagnosis of Barretts esophagus is made, surveillance guidelines may be helpful; however, it is important to remember that no current data show that surveillance decreases the rate of mortality. Further study and future treatments may bring more answers and, perhaps, better outcomes.

The authors indicate that they do not have any conflicts of interest. Sources of funding: none

Strength of Recommendations

Key clinical recommendation Patients with chronic GERD symptoms are those most likely to have Barretts esophagus and should undergo upper endoscopy. Recent evaluations of surgical therapy, such as fundoplication, showed no significant decrease in the risk of adenocarcinoma compared with medical therapy. As in screening, no evidence has shown that surveillance favorably affects mortality. Strength of recommendation C References 3

21

22,23

MAY 1, 2004 / VOLUME 69, NUMBER 9

www.aafp.org/afp

AMERICAN FAMILY PHYSICIAN-2117

Barretts Esophagus

reported.

REFERENCES 1. Barrett NR. Chronic peptic ulcer of the oesophagus and oesophagitis. Br J Surg 1950;38:175-82. 2. Spechler SJ. Clinical practice: Barretts esophagus. N Engl J Med 2002;346:836-42. 3. Sampliner RE, for the Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. Updated guidelines for the diagnosis, surveillance, and therapy of Barretts esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol 2002;97:1888-95. 4. Locke GR 3d, Talley NJ, Fett SL, Zinsmeister AR, Melton LJ 3d. Prevalence and clinical spectrum of gastroesophageal reflux: a population-based study in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Gastroenterology 1997;112:1448-56. 5. Gerson LB, Shetler K, Triadafilopoulos G. Prevalence of Barretts esophagus in asymptomatic individuals. Gastroenterology 2002;123:461-7. 6. Devesa SS, Blot WJ, Fraumeni JF Jr. Changing patterns in the incidence of esophageal and gastric carcinoma in the United States. Cancer 1998;83: 2049-53. 7. Dulai GS, Guha S, Kahn KL, Gornbein J, Weinstein WM. Preoperative prevalence of Barretts esophagus in esophageal adenocarcinoma: a systematic review. Gastroenterology 2002;122:26-33. 8. Weston AP, Banerjee SK, Sharma P, Tran TM, Richards R, Cherian R. P53 protein overexpression in low grade dysplasia (LGD) in Barretts esophagus: immunohistochemical marker predictive of progression. Am J Gastroenterol 2001;96:1355-62. 9. Shaheen NJ, Crosby MA, Bozymski EM, Sandler RS. Is there publication bias in the reporting of cancer risk in Barretts esophagus? Gastroenterology 2000;119:333-8. 10. Gopal DV, Lieberman DA, Magaret N, Fennerty MB, Sampliner RE, Garewal HS, et al. Risk factors for dysplasia in patients with Barretts esophagus (BE): results from a multicenter consortium. Dig Dis Sci 2003;48:1537-41. 11. Spechler SJ. A 59-year-old woman with gastroesophageal reflux disease and Barrett esophagus. JAMA 2003;289:466-75. 12. Lagergren J, Bergstrom R, Lindgren A, Nyren O. Symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux as a risk factor for esophageal adenocarcinoma. N Engl J Med 1999;340:825-31. 13. Bersentes K, Fass R, Padda S, Johnson C, Sampliner RE. Prevalence of Barretts esophagus in Hispanics is similar to Caucasians. Dig Dis Sci 1998;43:103841. 14. Cameron AJ, Lomboy CT. Barretts esophagus: age, prevalence, and extent of columnar epithelium. Gastroenterology 1992;103:1241-5. 15. Lagergren J, Bergstrom R, Nyren O. Association between body mass and adenocarcinoma of the esophagus and gastric cardia. Ann Intern Med 1999;130:883-90. 16. Gammon MD, Schoenberg JB, Ahsan H, Risch HA, 17.

18. 19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25. 26. 27.

28. 29. 30.

31.

Vaughan TL, Chow WH, et al. Tobacco, alcohol, and socioeconomic status and adenocarcinomas of the esophagus and gastric cardia. J Natl Cancer Inst 1997;89:1277-84. Inadomi JM, Sampliner R, Lagergren J, Lieberman D, Fendrick AM, Vakil N. Screening and surveillance for Barrett esophagus in high-risk groups: a costutility analysis. Ann Intern Med 2003;138:176-86. Spechler SJ. Barretts esophagus and esophageal adenocarcinoma: pathogenesis, diagnosis, and therapy. Med Clin North Am 2002;86:1423-45. Spechler SJ, Lee E, Ahnen D, Goyal RK, Hirano I, Ramirez F, et al. Long-term outcome of medical and surgical therapies for gastroesophageal reflux disease: follow-up of a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2001;285:2331-8. Ouatu-Lascar R, Triadafilopoulos G. Complete elimination of reflux symptoms does not guarantee normalization of intraesophageal acid reflux in patients with Barretts esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol 1998;93:711-6. Corey KE, Schmitz SM, Shaheen NJ. Does a surgical antireflux procedure decrease the incidence of esophageal adenocarcinoma in Barretts esophagus? A meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol 2003; 98:2390-4. Hurschler D, Borovicka J, Neuweiler J, Oehlschlegel C, Sagmeister M, Meyenberger C, et al. Increased detection rates of Barretts oesophagus without rise in incidence of oesophageal adenocarcinoma. Swiss Med Wkly 2003;133:507-14. Conio M, Blanchi S, Lapertosa G, Ferraris R, Sablich R, Marchi S, et al. Long-term endoscopic surveillance of patients with Barretts esophagus. Incidence of dysplasia and adenocarcinoma: a prospective study. Am J Gastroenterol 2003;98:1931-9. Eckardt VF, Kanzler G, Bernhard G. Life expectancy and cancer risk in patients with Barretts esophagus: a prospective controlled investigation. Am J Med 2001;111:33-7. Lambert R. Barretts oesophagus: better left alone? Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2001;13:627-30. Wright TA, Gray MR, Morris AI, Gilmore IT, Ellis A, Smart HL, et al. Cost effectiveness of detecting Barretts cancer. Gut 1996;39:574-9. Streitz JM Jr, Ellis FH Jr, Tilden RL, Erickson RV. Endoscopic surveillance of Barretts esophagus: a cost-effectiveness comparison with mammographic surveillance for breast cancer. Am J Gastroenterol 1998;93:911-5. Falk GW. Barretts esophagus. Gastroenterology 2002;122:1569-91. Eisen GM. Ablation therapy for Barretts esophagus. Gastrointest Endosc 2003;58:760-9. Graham DY, Yamaoka Y. H. pylori and cagA: relationships with gastric cancer, duodenal ulcer, and reflux esophagitis and its complications. Helicobacter 1998;3:145-51. DeVault KR, Castell DO, for the Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. Updated guidelines for the diagnosis and

2118-AMERICAN FAMILY PHYSICIAN

www.aafp.org/afp

VOLUME 69, NUMBER 9 / MAY 1, 2004

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- MiraLax (Polyethylene Glycol)Dokumen1 halamanMiraLax (Polyethylene Glycol)E100% (2)

- Whipple ProcedureDokumen8 halamanWhipple ProcedureDae AhmadBelum ada peringkat

- Enteral Stenting: How, Why and When?Dokumen25 halamanEnteral Stenting: How, Why and When?Nikhil BhangaleBelum ada peringkat

- Esofago de Barret - Lectura SemanalDokumen16 halamanEsofago de Barret - Lectura SemanalMauricio Alamillo BeuretBelum ada peringkat

- Propedeutics - Barrett's Esophagus - SMSDokumen18 halamanPropedeutics - Barrett's Esophagus - SMSSafeer VarkalaBelum ada peringkat

- Barrett EsophagusDokumen19 halamanBarrett Esophaguslaura correaBelum ada peringkat

- Barrett EsophagusDokumen12 halamanBarrett Esophaguseztouch12Belum ada peringkat

- Barrett's Esophagus (British English: Oesophagus) (Sometimes Called Barrett's Syndrome, CELLODokumen3 halamanBarrett's Esophagus (British English: Oesophagus) (Sometimes Called Barrett's Syndrome, CELLOMarlon CalatravaBelum ada peringkat

- Barrett Esophagus: Ekaterine Labadze MDDokumen13 halamanBarrett Esophagus: Ekaterine Labadze MDsushant jainBelum ada peringkat

- Barrett's Esophagus: Identifying The Squamocolumnar (SC) and Gastroesophageal (GE) Junctions EndoscopicallyDokumen10 halamanBarrett's Esophagus: Identifying The Squamocolumnar (SC) and Gastroesophageal (GE) Junctions Endoscopically1234chocoBelum ada peringkat

- Barretts EsofagusDokumen6 halamanBarretts EsofagusardiannwBelum ada peringkat

- Barrett's EsophagusDokumen10 halamanBarrett's EsophagusaryadroettninguBelum ada peringkat

- 13 Whitson2015Dokumen17 halaman13 Whitson2015Natalindah Jokiem Woecandra T. D.Belum ada peringkat

- Esophageal Cancer PDFDokumen16 halamanEsophageal Cancer PDFAJ AYBelum ada peringkat

- Barrett's Esophagus - Pathogenesis and Malignant Transformation - UpToDateDokumen12 halamanBarrett's Esophagus - Pathogenesis and Malignant Transformation - UpToDateyessyBelum ada peringkat

- Esophageal CarcinomaDokumen11 halamanEsophageal CarcinomaFRM2012Belum ada peringkat

- Biomarkers in Barrett's Esophagus and Esophageal Adenocarcinoma: Predictors of Progression and PrognosisDokumen13 halamanBiomarkers in Barrett's Esophagus and Esophageal Adenocarcinoma: Predictors of Progression and PrognosisCarlos HidalgoBelum ada peringkat

- Barrett'S Esophagus: Minesh Mehta, PGY-4 University of Louisville Department of GastroenterologyDokumen54 halamanBarrett'S Esophagus: Minesh Mehta, PGY-4 University of Louisville Department of Gastroenterologymadhumitha srinivasBelum ada peringkat

- Barrett Esophagus Rapid Evidence Review - AAFP 2022Dokumen5 halamanBarrett Esophagus Rapid Evidence Review - AAFP 2022ANDREA LORENA GALINDO ORELLANABelum ada peringkat

- Acid Related DisordersDokumen18 halamanAcid Related DisordersMinto SanjoyoBelum ada peringkat

- Who De®nes Barrett's Oesophagus: Endoscopist or Pathologist?Dokumen3 halamanWho De®nes Barrett's Oesophagus: Endoscopist or Pathologist?Servio CordovaBelum ada peringkat

- Rge ShackelfordDokumen14 halamanRge ShackelfordLuis FelipeBelum ada peringkat

- Barrett OesephegusDokumen22 halamanBarrett Oesephegusnour mohammadBelum ada peringkat

- Cancer de EsófagoDokumen12 halamanCancer de EsófagoJuan Jose Sanchez HuamanBelum ada peringkat

- Gastric VolvulusDokumen6 halamanGastric VolvulusIosif SzantoBelum ada peringkat

- Gastric CancerDokumen100 halamanGastric CancerJunior Más FlowBelum ada peringkat

- 1 s2.0 S1015958416302019 MainDokumen6 halaman1 s2.0 S1015958416302019 MainrosianaBelum ada peringkat

- Esophageal Cancer - Current Diagnosis and Management - Journal of Clinical Outcomes ManagementDokumen20 halamanEsophageal Cancer - Current Diagnosis and Management - Journal of Clinical Outcomes ManagementAstrini Retno PermatasariBelum ada peringkat

- BarrettDokumen6 halamanBarrettdbhangui6528Belum ada peringkat

- Barrett 'S EsophagusDokumen3 halamanBarrett 'S EsophagusI'Jaz Farritz MuhammadBelum ada peringkat

- ACG 2015 Barretts Esophagus GuidelineDokumen21 halamanACG 2015 Barretts Esophagus GuidelineFabrizzio BardalesBelum ada peringkat

- Esofago de BarretDokumen22 halamanEsofago de BarretJERSON SAMUEL ALCANTARA RAMOSBelum ada peringkat

- 2019 NatureReviews BarrettDokumen22 halaman2019 NatureReviews BarrettNicol OrtegaBelum ada peringkat

- 5) EndosDokumen12 halaman5) EndospbchantaBelum ada peringkat

- Pathophy ExplanationDokumen5 halamanPathophy ExplanationNicolette LeeBelum ada peringkat

- Barrett's Esophagus: Stuart Jon Spechler, M.DDokumen38 halamanBarrett's Esophagus: Stuart Jon Spechler, M.DMike AndrewBelum ada peringkat

- Barrett's Esophagus: Clinical PracticeDokumen9 halamanBarrett's Esophagus: Clinical PracticeHugo MarizBelum ada peringkat

- Gastroesophageal Reflux DiseaseDokumen4 halamanGastroesophageal Reflux DiseasemariatheressamercadoBelum ada peringkat

- Achalasia CardiaDokumen3 halamanAchalasia CardiaAnonymous KaJImISFBelum ada peringkat

- 1 s2.0 S0889855315000412 MainDokumen5 halaman1 s2.0 S0889855315000412 MainLeslie De La CruzBelum ada peringkat

- DiverticularDiseaseoftheColon PDFDokumen12 halamanDiverticularDiseaseoftheColon PDFAdrian MucileanuBelum ada peringkat

- ACG Guideline GERD March 2013 Plus CorrigendumDokumen22 halamanACG Guideline GERD March 2013 Plus Corrigendumdwifit3Belum ada peringkat

- Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease and Non-Esophageal CancerDokumen6 halamanGastroesophageal Reflux Disease and Non-Esophageal Cancerfernando herbellaBelum ada peringkat

- Barretts EsophagusDokumen7 halamanBarretts EsophagusRehan khan NCSBelum ada peringkat

- Esophageal Malignancy: A Growing Concern: ISSN 1007-9327 (Print) ISSN 2219-2840 (Online) Doi:10.3748/wjg.v18.i45.6521Dokumen6 halamanEsophageal Malignancy: A Growing Concern: ISSN 1007-9327 (Print) ISSN 2219-2840 (Online) Doi:10.3748/wjg.v18.i45.6521Agus KarsetiyonoBelum ada peringkat

- Gastric Adenocarcinoma Surgery and Adjuvant TherapyDokumen39 halamanGastric Adenocarcinoma Surgery and Adjuvant Therapyeztouch12Belum ada peringkat

- Epidemiology, Genetics and Screening For Oesophageal and Gastric CancerDokumen14 halamanEpidemiology, Genetics and Screening For Oesophageal and Gastric CancerLuis FelipeBelum ada peringkat

- Jurnal Esophageal CancerDokumen12 halamanJurnal Esophageal Cancerazza khalidahBelum ada peringkat

- Liver Abscess DissertationDokumen4 halamanLiver Abscess DissertationPayForAPaperAtlanta100% (1)

- JGastr10 GERDDokumen8 halamanJGastr10 GERDEnderBelum ada peringkat

- Managing Chronic Diarrhea With Colorectal Cancer: Symptom Management SeriesDokumen7 halamanManaging Chronic Diarrhea With Colorectal Cancer: Symptom Management SeriescindyBelum ada peringkat

- Esophageal CancerDokumen8 halamanEsophageal CancerSakthiswaran RajaBelum ada peringkat

- Cancro GastricoDokumen6 halamanCancro GastricoDani SBelum ada peringkat

- Gastric CancerDokumen9 halamanGastric CancerResya I. NoerBelum ada peringkat

- Journal of Gastroenterology and HepatologyDokumen9 halamanJournal of Gastroenterology and HepatologyKyla OcampoBelum ada peringkat

- Tugas GerdDokumen6 halamanTugas GerdMarc Chagall René MagritteBelum ada peringkat

- Ce 48 291Dokumen6 halamanCe 48 291Siska HarapanBelum ada peringkat

- Background: Anatomic AspectsDokumen19 halamanBackground: Anatomic AspectszgothicaBelum ada peringkat

- Torlutter2018 (Risk Factors)Dokumen7 halamanTorlutter2018 (Risk Factors)askhaeraniBelum ada peringkat

- Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease Control of Symptoms, Prevention of ComplicationsDokumen9 halamanGastroesophageal Reflux Disease Control of Symptoms, Prevention of ComplicationsTiurma SibaraniBelum ada peringkat

- Barrett’s Esophagus, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsDari EverandBarrett’s Esophagus, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsBelum ada peringkat

- Ureteral CalculiDokumen177 halamanUreteral CalculiSi vis pacem...Belum ada peringkat

- Historical Linguistics 2010Dokumen51 halamanHistorical Linguistics 2010Si vis pacem...Belum ada peringkat

- BASH Intermediate Care GuidanceDokumen21 halamanBASH Intermediate Care GuidanceBeboh PhotowindyBelum ada peringkat

- BASH Guidelines 2007Dokumen52 halamanBASH Guidelines 2007markspencerwhitingBelum ada peringkat

- Dictionary - Hebrew To EnglishDokumen789 halamanDictionary - Hebrew To EnglishPantoş Emilian Sergiu100% (1)

- A Student Vocabulary For Biblical HebrewDokumen113 halamanA Student Vocabulary For Biblical HebrewSi vis pacem...100% (1)

- 2007 Esh Esc GuidelinesDokumen83 halaman2007 Esh Esc GuidelinesSi vis pacem...Belum ada peringkat

- Trigeminal NeuralgiaDokumen6 halamanTrigeminal NeuralgiamimirkuBelum ada peringkat

- Incidental Renal and Adrenal MassesDokumen7 halamanIncidental Renal and Adrenal MassesSi vis pacem...Belum ada peringkat

- Evaluation of MacrocytosisDokumen6 halamanEvaluation of MacrocytosisSi vis pacem...Belum ada peringkat

- Alpha and Beta ThalassemiaDokumen6 halamanAlpha and Beta ThalassemiaSi vis pacem...100% (1)

- P 663Dokumen10 halamanP 663Si vis pacem...Belum ada peringkat

- Bladder Cancer LancetDokumen11 halamanBladder Cancer LancetYesenia HuertaBelum ada peringkat

- Dysuria in AdultsDokumen8 halamanDysuria in AdultsSi vis pacem...Belum ada peringkat

- Ectopic Pregnancy-American Family PhysicianDokumen8 halamanEctopic Pregnancy-American Family PhysicianSi vis pacem...Belum ada peringkat

- Common Anorectal Conditions:: Part I. Symptoms and ComplaintsDokumen8 halamanCommon Anorectal Conditions:: Part I. Symptoms and ComplaintsSi vis pacem...Belum ada peringkat

- Psychiatric Medications During PregnancyDokumen8 halamanPsychiatric Medications During PregnancySi vis pacem...Belum ada peringkat

- Congenital ToxoplasmosisDokumen8 halamanCongenital ToxoplasmosisSi vis pacem...Belum ada peringkat

- Chronic Vulvovaginal CandidiasisDokumen6 halamanChronic Vulvovaginal CandidiasisSi vis pacem...Belum ada peringkat

- Hepatitis ADokumen7 halamanHepatitis ASi vis pacem...Belum ada peringkat

- Review Scolio Am Fam Phys 2001Dokumen6 halamanReview Scolio Am Fam Phys 2001Raimundo Vial IrarrázavalBelum ada peringkat

- Chronic PancreatitisDokumen10 halamanChronic PancreatitisMichael WongBelum ada peringkat

- C Difficile DiarrheaDokumen12 halamanC Difficile DiarrheaSi vis pacem...Belum ada peringkat

- Chronic Shoulder Pain - Part I Evaluation & DiagnosisDokumen8 halamanChronic Shoulder Pain - Part I Evaluation & Diagnosisgozjasa100% (1)

- Urticaria - Evaluation and Treatment - May 1, 2011 - American Family PhysicianDokumen8 halamanUrticaria - Evaluation and Treatment - May 1, 2011 - American Family PhysicianSi vis pacem...Belum ada peringkat

- Gout An UpdateDokumen8 halamanGout An UpdateSi vis pacem...Belum ada peringkat

- Allergen ImmunotherapyDokumen8 halamanAllergen ImmunotherapyIswahyudi AlamsyahBelum ada peringkat

- FIGURE 3-332 Approach To The Unconscious Patient. ABG, Arterial Blood Gas ALT, Alanine Aminotransferase ASTDokumen8 halamanFIGURE 3-332 Approach To The Unconscious Patient. ABG, Arterial Blood Gas ALT, Alanine Aminotransferase ASTSi vis pacem...Belum ada peringkat

- PericarditisDokumen8 halamanPericarditisSi vis pacem...Belum ada peringkat

- Nursing Care Plan - FormatDokumen6 halamanNursing Care Plan - FormatKyle VargasBelum ada peringkat

- Care of Adults 27 Gastrointestinal ManagementDokumen33 halamanCare of Adults 27 Gastrointestinal ManagementGaras AnnaBerniceBelum ada peringkat

- Gastroenterology EsophagusDokumen2 halamanGastroenterology EsophagusJayanthBelum ada peringkat

- JaundiceDokumen18 halamanJaundiceafeefa.gbgBelum ada peringkat

- Digestion Rate On FishDokumen8 halamanDigestion Rate On FishMellya RizkiBelum ada peringkat

- The Anatomy, Histology and Development of The Stomach PDFDokumen7 halamanThe Anatomy, Histology and Development of The Stomach PDFredderdatBelum ada peringkat

- Science: Revision Guide by MalaikaDokumen7 halamanScience: Revision Guide by MalaikamalaikaBelum ada peringkat

- Dis LiverDokumen40 halamanDis LiverPrem MorhanBelum ada peringkat

- Hirschsprung Disease Case Study: Maecy P. Tarinay BSN 4-1Dokumen5 halamanHirschsprung Disease Case Study: Maecy P. Tarinay BSN 4-1Maecy OdegaardBelum ada peringkat

- Daftar ISI JurnalDokumen3 halamanDaftar ISI JurnalmarcoBelum ada peringkat

- Dr. Mochamad Aleq Sander, M.Kes., SP.B., FINACS: Sertifikasi Dosen: 12107102411578Dokumen31 halamanDr. Mochamad Aleq Sander, M.Kes., SP.B., FINACS: Sertifikasi Dosen: 12107102411578Alif riadiBelum ada peringkat

- MCQsDokumen32 halamanMCQsamBelum ada peringkat

- AppendicitisDokumen38 halamanAppendicitisEmaan Tanveer100% (1)

- Síndrome de MirizziDokumen5 halamanSíndrome de MirizziOmar DorantesBelum ada peringkat

- Diseases of Esophagus.Dokumen3 halamanDiseases of Esophagus.Isabel Castillo100% (2)

- Med Surg 2 - 8 Malabsorption Syndromes and Nursing Care of Clients With Hepatic DisordersDokumen8 halamanMed Surg 2 - 8 Malabsorption Syndromes and Nursing Care of Clients With Hepatic DisordersMaxinne RoseñoBelum ada peringkat

- Studi Kasus Kegagalan Pada HatiDokumen34 halamanStudi Kasus Kegagalan Pada HatiMarLeniRN100% (1)

- Foreign - Bodies - in - The - GI - Tract by DR Kassahun GirmaDokumen67 halamanForeign - Bodies - in - The - GI - Tract by DR Kassahun GirmaKassahun Girma GelawBelum ada peringkat

- Causes of Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding in Adults - UpToDateDokumen37 halamanCauses of Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding in Adults - UpToDateAline MoraisBelum ada peringkat

- FMG Marathon Surgery 17-12-22Dokumen58 halamanFMG Marathon Surgery 17-12-22Sumit GuptaBelum ada peringkat

- Radio - GitDokumen19 halamanRadio - GitVon HippoBelum ada peringkat

- Ulcerative Colitis 1. Chief ComplaintDokumen5 halamanUlcerative Colitis 1. Chief Complaintdrnareshkumar3281Belum ada peringkat

- Lactose Intolerance - Symptoms, Causes and Precautions - Dr. Samrat JankarDokumen4 halamanLactose Intolerance - Symptoms, Causes and Precautions - Dr. Samrat JankarDr. Samrat JankarBelum ada peringkat

- Hemorrhoids and Anal ProblemsDokumen64 halamanHemorrhoids and Anal ProblemsAhmed Noureldin Ahmed100% (3)

- Gastrointestinal Assessment PDFDokumen15 halamanGastrointestinal Assessment PDFJinaan MahmudBelum ada peringkat

- Script BGDDokumen2 halamanScript BGDTrina CardonaBelum ada peringkat

- Nasogastric Tube FeedingDokumen7 halamanNasogastric Tube FeedingVina Empiales100% (1)

- Anatomi & Fisiologi Sal CernaDokumen29 halamanAnatomi & Fisiologi Sal Cernabeni kurniawanBelum ada peringkat