Leseprobe01

Diunggah oleh

Fadli NoorJudul Asli

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Leseprobe01

Diunggah oleh

Fadli NoorHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

One

The Election of a Lifetime

Mitchell S. McKinney and Mary C. Banwart

he most important election of our lifetime was a claim heard repeatedly throughout the 2008 campaign from candidates and media pundits, to citizens of all ages. While many presidential elections become nothing more than a mere footnote in history, the 2008 campaign and election changed history. Certainly, Barack Obamas nomination and eventual election as the nations first black president was a momentous feature of the historic 2008 campaign. Yet, beyond Obamas election as the 44th president of the United States, other important elements of this historic electoral contest are worth noting, andfor students and scholars of political communicationworthy of careful examination. For example, candidate gender played a significant role in campaign 2008, including Hillary Rodham Clintons primary candidacy that resulted in 18 million cracks in that highest, hardest glass ceiling (Millbank, 2008), as well as Sarah Palins vice presidential candidacyonly the second time in U.S. politics that a majorparty ticket included a female candidate. Even John McCains selection as the Republican presidential nominee was historic, as McCain, had he been victorious in November of 2008, would have become the oldest person ever inaugurated president of the United States. As if this litany of firsts were not enough, the electoral performance of young citizens provided yet another history-making element to campaign 2008. The Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning and Engagement (CIRCLE) reports that approximately 51% of young citizens (18- to 29-year-olds)

2 Mitchell S. McKinney and Mary C. Banwart

cast a ballot in 2008, the third highest rate of participation by young voters in a presidential election since 1972 (New Census Data Confirm Increase in Youth Voter Turnout, 2009).1 In fact, the 2008 election is the third presidential election in a row in which the percentage of young voter turnout has risen (with a 40% turnout of 18-to 29-year-olds in 2000 followed by 49% in 2004). While young voters increased their 2008 turnout, the rate of older citizens voting (those 30 and over) actually declined from their 2004 level of participationthe very first time since 1972, when 18-year-olds first voted in a presidential election, that young voter participation rose while older citizens participation decreased. Finally, in 2008, 18- to 29-year old African American voters achieved the highest turnout ever recorded (58%) by any racial or ethnic group of young citizens; and 2008 was the very first time the percentage of registered young African American voters outnumbered young white voters (New Census Data Confirm Increase in Youth Voter Turnout, 2009). Young voters overwhelming support for the Democratic candidate Barack Obama offers yet another notable feature of the 2008 vote. Across all age groups (see figure 1), young citizens provided Obama with his widest margin of support as these voters, by more than two to one (68% to 32%), chose Obama over John McCain. What was it that attracted so many of our youngest citizens to Barack Obama? Indeed, throughout the election much was made of team Obamas ability to identify with, organize, and turn out this generation of digital nativescitizens for whom digital technologies have been part of their entire livesby devel-

Figure 1: Voter Preference by Age

Source: Young Voters in the 2008 Presidential Election (www.civicyouth.org)

The Election of a Lifetime 3

oping campaign messages and appeals that used the very communicative practices and language of these young citizens (Palfrey & Gasser, 2008). The New York Times went so far as to label his loyal following Generation O (as in Obama). The multitude of young Obama supporters exhibited a seemingly personal relationship with their candidate, forged by a steady stream of digital communication as typified in the exchange that took place just seconds after the networks called the election for Barack Obama. Even before he addressed the nation and the world to herald his historic victory, the president-elect first texted his throng of digital followers with a text signed simply Barack and informing them Im about to head to Grant Park to talk to everyone, but I wanted to write to you first. All of this happened because of you... we just made history (Cave, 2008). From YouTube to Twitter, to blogs, texting, and social networking, a variety of new forms and channels of communication emerged as a key feature of campaign 2008. Historian Max Friedman (2009, p. 343) concluded, this was the election in which new media played a more important role than ever before in American history. The Pew Internet and American Life Project (2008) found that nearly half of all Americans (46%) reported using the Internet to get news about the 2008 campaign. Clearly, in the emerging era of digital politics, this election demonstrated that candidates campaign communication must now meet the expectations and communicative practices of a growing number of netizens whose political engagement is increasingly performed through various forms of digital messaging. In describing the leading candidates technologized images, Friedman (2009) suggests we might best comprehend the publics 2008 presidential decision by understanding: . . . the hip sensibility of Obamas campaign versus the old-school consultants around the Clinton machine, and it becomes clear why the leading Democratic campaigns were sometimes compared to the clash between Apple and Microsoft. Obama was the Mac, of course: youthful, creative, nimble, forward-looking, and sleekly stylish; Clinton was the PCmassive, corporate, sitting atop a huge pile of capital and a legacy of brand recognition and market share that favored a conventional, risk-averse strategy struggling to patch over the basic flaws in its original design. John McCain, though... who had never sent an e-mail... was an IBM Selectric. (p. 344) The central thesis of this book is not to suggest that Barack Obama became president of the United States simply because he was more skillful than his opponents in adopting the Internet and digital technologies as a campaign communication tool. Presidential campaigns are won and lost based on a myriad of reasons, including, among other factors, candidates abilities to successfully frame

4 Mitchell S. McKinney and Mary C. Banwart

their message (the crafting of a vision and development of image) while also attempting to frame their opponent in desired ways, the ability to strategically craft and target appropriate messages for particular audiences, the ability to mobilize ones base supporters, and, of course, the ability to raise the hundreds of millions of dollars now needed to wage a successful presidential campaign. We hope it is clear that our conceptulazation of a presidential campaign is grounded in communication, a process that includes communicator (candidate) crafting persuasive appeals (message/image) for desired audiences (targeted voters) and delivered via appropriate communication channels or media. In the end, we do believe that winning and losing an election has much to do with a candidates ability to communicate effectivelyor not. As one traces the history of American campaigning and elections, a parallel history of the development of communication media and technologies is useful (see, for example, Schudsons The Good Citizen, 1998). From handbills and broadsides, to party parades and the rise of the partisan press, to Lincoln and Douglas debating, FDRs radio chats, Eisenhowers televised campaign spots, Kennedy and Nixons televised debates, to Bill Clintons boxers or briefs on MTV and saxophone and shades on Arsenio Hall, political leaders and candidates have long sought innovative ways, often adopting the latest in communication media and technologies, to reach the public with their pleas. Our abbreviated chronicling of these few highand perhaps some lowpoints in political communication history demonstrates the evolutionary nature of political campaign communication. We realize, too, that the arrival of the so-called digital revolution in political communicating did not instantaneously emerge in campaign 2008. For well over a decade, the Internet and so-called new digital technologies were evolving as an increasingly important part of our political communication landscape. After very limited use of the just emerging Internet during his 1992 campaign, Bill Clinton launched the first White House web site in 1994 (Whillock, 1997); and within the next few years, and certainly by 2000, web sites and e-mail lists were common communication tools and practices for political office holders and candidates at all levels. Perhaps as a prelude to campaign 2008, Howard Deans 2004 Democratic presidential primary bid demonstrated the Internets social networking utility for political campaigning as thousands of supporters were organized through meet ups and mobilized as Dean campaign volunteers. The Dean campaign also established the Internets effectiveness as a tool for raising campaign cash (Trippi, 2004). Finally, before Obama Girl went viral in 2008, or even before Hillary Clintons primary campaign was spoofed in 2007 with the Hillary 1984 Apple parody ad (titled Vote Different), the power of citizengenerated video in political campaigns was discovered by U.S. Senate candidate George Allen in 2006 when he was filmed at a rural Virginia campaign rally by

The Election of a Lifetime 5

a staffer working for his opponent who uploaded Allens macaca moment to a video-sharing web site that had been in existence for just over a year, YouTube. Thus, by 2008, the digital revolution in presidential campaign communication was ripe, and BarackObama.com was there to lead the revolution. Friedman (2009, p. 345) provides this description of Obamas digital campaign operation: ninety paid staffers on the Obama Internet team, who built a 13 million address e-mail list, sending out more than 1 billion e-mail messages by election day, maintaining an Obama presence on fifteen different social networking sitessuch as MySpace, Facebook, and BlackPlanetwith over 2 million supporters profiles created on MyBarackObama.com, with these volunteers organizing approximately 200,000 meet up events, and, on election day alone, Obamas Facebook friends sent over 5 million messages reporting they had just cast their ballot for Barack Obama and urging their friends to do the same. Our focus on Barack Obamas use of digital technologies in campaign 2008, and his apparent success in attracting young voters to his cause, serves as illustration to support the two central themes developed throughout this volume of campaign communication studies. First, the 2008 campaign, we feel, provides an excellent case studyperhaps something of a turning point in campaign communicationfor us to carefully examine the emerging role of digital political media. Second, as documented earlier in this chapter, available data also suggest a continuing renewal in young citizens electoral engagement. Again, after young citizens recorded their lowest level of voting in 1996 (at 39%), weve now witnessed three successive presidential elections in which the number of young citizens who vote has increased; and, during this same period, the gap between more older vs. fewer younger citizens voting has diminished with each election since 2000 (New Census Data Confirm Increase in Youth Voter Turnout, 2009).2 Thus, with more young citizens voting, particularly during the emerging era of digital politics, can we conclude that this revival of young citizen engagement is fueled by our first generation of digital natives responding to political campaigning that utilizes this generations common communicative practices and language? In fact, we have little empirical evidence to help us understand ifand perhaps even more importantly howvarious forms of digital campaign communication might work to engage young citizens in the electoral process. The research studies that follow examine the content and effects of various sources of political information, with particular emphasis on the wide range of political digital media and how such campaign communication influences young citizens. The books first sectionCommunication for & by Digital Natives in Campaign 2008features a series of studies examining various forms of digital campaign communication as well as the communicative behaviors of young citizens. In Chapter 2, The Complex Web: Young Adults Opinions about Online Campaign Messages, John Tedesco reports the results of an experimental study

6 Mitchell S. McKinney and Mary C. Banwart

evaluating the effects of specific Internet web and video campaign messages on young citizens political information efficacy and political engagement; in Chapter 3, Viral Politics: The Credibility and Effects of Online Viral Political Messages, Monica Ancu, also through experimental analysis, assesses the perceived credibility of YouTube viral political videos, and determines how viral Internet ads affect viewers perceptions of political candidates; in Chapter 4, Talking Politics: Young Citizens Interpersonal Interaction during the 2008 Presidential Campaign, Leslie Rill and Mitchell McKinney report the results of a longitudinal study examining young citizens political talk throughout the 2008 campaign season, including how often individuals engage in political talk during the ongoing presidential campaign, with whom they most frequently talk politics, and the relationship between these young citizens political media diet and their political talk behaviors; in Chapter 5, A Different Kind of Inter-media Agenda Setting: How Campaign Ads Influenced the Blogosphere in the 2008 U.S. Election, Sumana Chattopadhyay and Molly Greenwood compare the issue agendas of traditional and digital campaign media, including campaign issues featured in Barack Obama and John McCains YouTube ads, the issues discussed by the candidates during their televised presidential debates, and campaign issues discussed by citizens posts to partisan Internet blogs; and, finally, in Chapter 6, Political Advertising, Digital Fundraising and Campaign Finance in the 2008 Election, Clifford Jones provides a detailed case analysis of Barack Obamas digital fundraising operation that resulted in Obama raising more than $745 million, an unprecedented amount in presidential campaign history. While a major focus of this book is an examination of digital campaign media, more traditional modes and forms of campaign communication continue to be an important element of candidates campaign communication repertoire. The studies found in section two, Candidate Messages & Images in Campaign 2008, analyze both content and effects of presidential advertising, debates, stump speeches, and news coverage. In Chapter 7, The Cumulative Effects of Televised Presidential Debates on Voters Attitudes across Red, Blue, and Purple Political Playgrounds, Yun and colleagues analyze assessments of Obama and McCains debate performances and, utilizing experimental data collected nationally, they investigate the influence of debate viewers geopolitical statuswhether one hails from a battleground (purple), Obama (blue) or McCain (red) state; in Chapter 8, Political Engagement through Presidential Debates: Attitudes of Political Engagement throughout the 2008 Election, McKinney and colleagues report the results of a panel study that first tests the effects of young citizens exposure to presidential debates, and then tracks these same citizens and their attitudes of democratic engagement throughout the course of the 2008 campaign; in Chapter 9, Can YOU Hear Me Now? Identifying the Audience in 2008 Primary and General Election Presidential Political Advertisements, Jerry Miller content analyzes several hundred

The Election of a Lifetime 7

(n = 374) primary and general election presidential ads from the 2008 campaign, examining the extent to which these ad messages contribute to a dividing of the electorate through the rhetoric of othering; in Chapter 10, Talking to Millennials: Policy Rhetoric and Rhetorical Narratives in the 2008 Presidential Campaign, Alison Howard and Donna Hoffman examine the campaign speeches of John McCain and Barack Obama and the specific rhetorical strategies and appeals used to target young citizens; and, finally, in Chapter 11, Snap Judgments: A Study of Newsmagazine Photographs in the 2008 Presidential Campaign, Karla Hunter and colleagues conduct a visual content analysis of nearly 700 photographs from major U.S. newsmagazines, evaluating the medias visual portrayal of Hillary Clinton, Barack Obama and John McCain and examining the extent to which visual bias was present in the medias photographic coverage of the leading presidential candidates. As we noted earlier, candidate gender played a significant role in campaign 2008, including Hillary Rodham Clintons primary candidacy, as well as Sarah Palins vice presidential candidacy. Section three, Female Candidates in Campaign 2008, features three studies that focus on candidate gender. First, in Chapter 12, Running Down Ballot: Reactions to Female and Male Candidate Messages, Benjamin Warner and colleagues study young voters evaluations of female and male congressional candidates campaign ads, specifically examining how these voters sexist beliefs, identification with ones own gender, and identification with the gender of the candidate influence their evaluations of the candidates; in Chapter 13, Videostyle 2008: A Comparison of Female vs. Male Political Candidate Television Ads, Dianne Bystrom and Narren Brown continue Bystroms longstanding content analytic work examining candidates political advertising videostyle an ads verbal, non-verbal, and film/video production techniquesanalyzing 236 campaign ads from mixed gender (male and female) races as well as races featuring two female candidates, with specific attention given to the videostyles used by candidates in four notable 2008 campaigns, including Hillary Clinton and Barack Obamas Democratic presidential primary contest, Elizabeth Dole and Kay Hagens North Carolina U.S. Senate race, Jeanne Shaheen and John Sununus New Hampshire U.S. Senate race, and Beverly Perdue and Pat McCrorys North Carolina gubernatorial campaign; and, finally, in Chapter 14, Motherhood, God & Country: Sarah Palins 68 Days in 2008, Julia Spiker explains the role played by Sarah Palin in the McCain presidential campaign, and through rhetorical analysis of Palins key campaign speeches describes Palins rhetorical style and most common appeals incorporated in her campaign discourse. The last section of this book, International Perspectives on Campaign 2008, recognizes that the election of a U.S. president, and particularly the 2008 ObamaMcCain contest, is an event heard round the world. The four studies in this section provide analysis of international medias coverage of the U.S. election,

8 Mitchell S. McKinney and Mary C. Banwart

international citizens perceptions of the U.S. and its 2008 presidential candidates, and also a case study of international journalists coverage of the U.S. presidential election. In Chapter 15, Perceptions of the U.S. and the 2008 Presidential Election from Young Citizens Around the World, Lynda Kaid and colleagues report the results of their multi-country (18-nation) survey of young citizens attitudes toward the U.S. and also these citizens evaluations of Barack Obama and John McCain; in Chapter 16, International Medias Love Affair with Barack Obama: Anti-Americanism and the Global Coverage of the 2008 Presidential Campaign, Jesper Strmbck and colleagues examine how the worlds press covered the 2008 U.S. presidential election, providing results of their content analysis of election stories found in the leading newspapers of 10 nations characterized by their varying levels of anti-American sentiment; in Chapter 17, German Press Coverage of the 2004 and 2008 U.S. Presidential Election Campaigns, Christian Holtz-Bacha and Reimar Zeh compare German press coverage of the last two U.S. presidential campaigns, with content analysis of election reporting from Germanys two most important daily newspapers, the liberal Sddeutschen Zeitung and the conservative Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung; and, finally, in Chapter 18, The Emerson Election Project: Indonesian Journalists Visit the U.S. during the 2008 Presidential Election, J. Gregory Payne and Efe Sevin provide a case study of the Emerson Election Project, a public diplomacy program sponsored by the U.S. Department of State, in which prominent journalists from Indonesiawhere Barack Obama lived and attended school for a short period during his youthcame to the U.S. during the final weeks of the presidential election and filed news reports for Indonesian audiences from several battleground states and major cities while they shadowed U.S. journalists. The wide-ranging studies that make up this book provide a comprehensive examination of a truly historic political campaign and election. While findings from the numerous empirical analyses offer revealing answers regarding the content and effects of various forms of political campaign communication, many more questions and possibilities for future research are raised. We know that todays new modes and practices of political communication will soon be replaced by tomorrows newest innovations in campaign communication. This, of course, is what makes our work both challenging and exciting. Indeed, we look forward to many more elections of a lifetime!

Endnotes

1. When 18-year-olds were first allowed to vote in 1972, young voters (18 to 29) achieved their high-water mark of electoral participation at 55.4%. In 1992, with an increase in young citizens turning out to vote for Bill Clinton, youth voting was at 52% (New Census Data Confirm Increase in Youth Voter Turnout, 2009).

The Election of a Lifetime 9 2. In 2000, voter turnout for 18- to 29-year olds was 40.3%, compared to 54.6% for citizens 30 and older (a 24.3% gap); in 2004, younger voters rate of voting was 49%, compared to older voters at 67.7% (an 18.7% gap); finally, in 2008, younger voters recorded a 51.1% rate of participation, compared to older voters 67% (a gap of 15.9%).

References

Cave, D. (2008, November 9). Generation O gets its hopes up. The New York Times, p. ST1. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2008/11/09/fashion/09boomers. html Friedman, M. P. (2009). Simulacrobama: The mediated election of 2008. Journal of American Studies, 43(2), 341356. Millbank, D. (2008, June 8). A thank-you for 18 million cracks in the glass ceiling. The Washington Post. Retrieved from http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/ article/2008/06/07/AR2008060701879.html New Census Data Confirm Increase in Youth Voter Turnout. (2009, April 28). The Center for Information & Research on Civic Learning & Engagement. Retrieved June 15, 2009 from www.civicyouth.org Palfrey, J., & Gasser, U. (2008). Born digital: Understanding the first generation of digital natives. New York: Basic Books. Pew Internet and American Life Project. (2008, June 15). The Internet and the 2008 election. Retrieved July 15, 2009 from www.pewinternet.org Schudson, M. (1998). The good citizen. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Trippi, J. (2004). The revolution will not be televised: Democracy, the Internet, and the overthrow of everything. New York: HarperCollins. Whillock, R. K. (1997). Cyber-politics: The online strategies of 96. American Behavioral Scientist, 40(8), 12081225. Young Voters in the 2008 Presidential Election. (2008, November 28). The Center for Information & Research on Civic Learning & Engagement. Retrieved January 15, 2009 from www.civicyouth.org

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (121)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (588)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (400)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (266)

- Tactical Radio BasicsDokumen46 halamanTactical Radio BasicsJeff Brissette100% (2)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5795)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (345)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (895)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- Writing White PapersDokumen194 halamanWriting White PapersPrasannaYalamanchili80% (5)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (74)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- Whats It All About - Framing in Political ScienceDokumen41 halamanWhats It All About - Framing in Political ScienceFadli NoorBelum ada peringkat

- Remedies FlowDokumen44 halamanRemedies Flowzeebeelo100% (1)

- Single Line DiagramDokumen1 halamanSingle Line DiagramGhanshyam Singh100% (2)

- XXX RadiographsDokumen48 halamanXXX RadiographsJoseph MidouBelum ada peringkat

- IEC947-5-1 Contactor Relay Utilization CategoryDokumen1 halamanIEC947-5-1 Contactor Relay Utilization CategoryipitwowoBelum ada peringkat

- EU MDR FlyerDokumen12 halamanEU MDR FlyermrudhulrajBelum ada peringkat

- Difference Between Art. 128 and 129 of The Labor CodeDokumen3 halamanDifference Between Art. 128 and 129 of The Labor CodeKarl0% (1)

- Manaloto V Veloso IIIDokumen4 halamanManaloto V Veloso IIIJan AquinoBelum ada peringkat

- Pecson Vs CADokumen3 halamanPecson Vs CASophiaFrancescaEspinosaBelum ada peringkat

- Lawson Borders 2005Dokumen13 halamanLawson Borders 2005Fadli NoorBelum ada peringkat

- In Genta 893Dokumen25 halamanIn Genta 893Fadli NoorBelum ada peringkat

- Out of The GateDokumen35 halamanOut of The GateFadli NoorBelum ada peringkat

- Five Things We Need To Know About Technological Change Neil PostmanDokumen5 halamanFive Things We Need To Know About Technological Change Neil PostmangpnasdemsulselBelum ada peringkat

- Viewpoint 090002Dokumen17 halamanViewpoint 090002Fadli NoorBelum ada peringkat

- Press/Politics The International Journal ofDokumen26 halamanPress/Politics The International Journal ofFadli NoorBelum ada peringkat

- CH 1Dokumen12 halamanCH 1Fadli NoorBelum ada peringkat

- Use of Public Record Databases in Newspaper and Television NewsroomsDokumen16 halamanUse of Public Record Databases in Newspaper and Television NewsroomsFadli NoorBelum ada peringkat

- Henderson Paradise Journal of Public RelationsDokumen22 halamanHenderson Paradise Journal of Public RelationsFadli NoorBelum ada peringkat

- The State, Democracy and The Limits of New Public Management: Exploring Alternative Models of E-GovernmentDokumen14 halamanThe State, Democracy and The Limits of New Public Management: Exploring Alternative Models of E-GovernmentFadli NoorBelum ada peringkat

- The Changing Face of Incumbency Joe Liebermans Digital Presentation of SelfDokumen25 halamanThe Changing Face of Incumbency Joe Liebermans Digital Presentation of SelfFadli NoorBelum ada peringkat

- Uses and Effects of New Media On Political Communication in The United States of America, Germany, and EgyptDokumen9 halamanUses and Effects of New Media On Political Communication in The United States of America, Germany, and EgyptFadli NoorBelum ada peringkat

- 60, Southwell, Interpersonal in Mass Media, 2007Dokumen34 halaman60, Southwell, Interpersonal in Mass Media, 2007Fadli NoorBelum ada peringkat

- 28 HirstDokumen5 halaman28 HirstFadli NoorBelum ada peringkat

- Jane MarceauDokumen36 halamanJane MarceauFadli NoorBelum ada peringkat

- Industrial Clusters and Establishment of Mit Fablab at Furuflaten, NorwayDokumen5 halamanIndustrial Clusters and Establishment of Mit Fablab at Furuflaten, NorwayFadli NoorBelum ada peringkat

- IhrkeDokumen26 halamanIhrkeFadli NoorBelum ada peringkat

- 2 Days Meat Processing Training Program (Kalayaan Laguna)Dokumen2 halaman2 Days Meat Processing Training Program (Kalayaan Laguna)Jals SaripadaBelum ada peringkat

- Contoh CV Pelaut Untuk CadetDokumen1 halamanContoh CV Pelaut Untuk CadetFadli Ramadhan100% (1)

- Aling MODEDokumen29 halamanAling MODEBojan PetronijevicBelum ada peringkat

- Revised Full Paper - Opportunities and Challenges of BitcoinDokumen13 halamanRevised Full Paper - Opportunities and Challenges of BitcoinREKHA V.Belum ada peringkat

- Soal Ujian SmaDokumen26 halamanSoal Ujian SmaAyu RiskyBelum ada peringkat

- Apples-to-Apples in Cross-Validation Studies: Pitfalls in Classifier Performance MeasurementDokumen9 halamanApples-to-Apples in Cross-Validation Studies: Pitfalls in Classifier Performance MeasurementLuis Martínez RamírezBelum ada peringkat

- The US Navy - Fact File - MQ-8C Fire ScoutDokumen2 halamanThe US Navy - Fact File - MQ-8C Fire ScoutAleksei KarpaevBelum ada peringkat

- Mid Semester Question Paper Programming in CDokumen8 halamanMid Semester Question Paper Programming in CbakaBelum ada peringkat

- GB Programme Chart: A B C D J IDokumen2 halamanGB Programme Chart: A B C D J IRyan MeltonBelum ada peringkat

- Sample Lesson Plan Baking Tools and EquipmentDokumen3 halamanSample Lesson Plan Baking Tools and EquipmentJoenel PabloBelum ada peringkat

- Claims Reserving With R: Chainladder-0.2.10 Package VignetteDokumen60 halamanClaims Reserving With R: Chainladder-0.2.10 Package Vignetteenrique gonzalez duranBelum ada peringkat

- Vishnu Institute of Technology: V2V CommunicationsDokumen22 halamanVishnu Institute of Technology: V2V CommunicationsBhanu PrakashBelum ada peringkat

- Spice Board BBLDokumen24 halamanSpice Board BBLvenkatpficoBelum ada peringkat

- sb485s rs232 A rs485Dokumen24 halamansb485s rs232 A rs485KAYCONSYSTECSLA KAYLA CONTROL SYSTEMBelum ada peringkat

- Namma Kalvi 12th Maths Chapter 4 Study Material em 213434Dokumen17 halamanNamma Kalvi 12th Maths Chapter 4 Study Material em 213434TSG gaming 12Belum ada peringkat

- Cronbach's AlphaDokumen4 halamanCronbach's AlphaHeide Orevillo Apa-apBelum ada peringkat

- SamanthavasquezresumeDokumen1 halamanSamanthavasquezresumeapi-278808369Belum ada peringkat

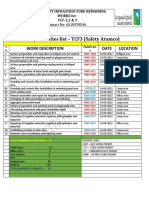

- Daily Activities List - TCF3 (Safety Aramco) : Work Description Date LocationDokumen2 halamanDaily Activities List - TCF3 (Safety Aramco) : Work Description Date LocationSheri DiĺlBelum ada peringkat

- CM760 E-Brochure HemobasculaDokumen6 halamanCM760 E-Brochure Hemobasculajordigs50Belum ada peringkat

- Case Study 1Dokumen2 halamanCase Study 1asad ee100% (1)