Speech & Language Therapy in Practice, Winter 2001

Diunggah oleh

Speech & Language Therapy in PracticeHak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Speech & Language Therapy in Practice, Winter 2001

Diunggah oleh

Speech & Language Therapy in PracticeHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Evaluation

Reflective diaries

User involvement

Seeking the whole truth

Objective assessment

Research report

Collaboration

Joint training

In my

experience

Making learning

meaningful

Expressive arts

A P O T E N T C O M B I N A T I O N

ISSN 1368-2105

vlNTER oo+

http://www.speechmag.com

How I use

music in

therapy

My top

resources

School aged

children

Winter 2001 speechmag

Reprinted articles to complement the

Winter 2001 issue of Speech & Language

Therapy in Practice

Putting parents perceptions first.

(October 1989, 5 (5))*

Linda Banks explains how the therapist-parent relationship

can get off to a good - or bad - start. She argues that

the first visit is a momentous occasion and deserves our

fullest consideration.

New skills are needed in adult mental

handicap. (January 1989, 4 (5))*

With the return of adults with learning difficulties into

the community, Susan Dobson found that skills needed

in this field had to be re-assessed.

Drake music project strikes the right note

for communication. (Nov/Dec 1995, 5 (1))**

The Drake Music Project aims to enable disabled people to

make music through technology. Adele Drake, Diane

Paterson and Leon Clowes describe their work.

Also on the site - contents of back issues and news about

the next one, links to other sites of practical value and

information about writing for the magazine. Pay us a

visit soon and try out our search facility.

Remember - you can also

subscribe or renew online

via a secure server!

From Speech Therapy in Practice*/Human

Communication**, courtesy of Hexagon Publishing, or

from Speech & Language Therapy in Practice***

w

w

w

.

s

p

e

e

c

h

m

a

g

.

c

o

m

READER OllERS

vn vorkng

wth Dysphaga

The caseloads of speech

and language therapists

are increasingly includ-

ing work with clients

with dysphagia. This

practical text by Lizzy

Marks and Deirdre

Rainbow is suitable for

a range of client

groups including those

with acquired neuro-

logical disorders and

those with learning

difficulties.

Reflecting current practice in the UK, the contents

include subjective and objective assessment, tra-

cheostomies and ventilators, and legal, health and

safety and ethical issues. Multidisciplinary working is

discussed, as is training other professionals.

Working with Dysphagia normally retails at 35.00

but Speechmark Publishing Ltd (formerly Winslow

Press) is making FIVE copies available FREE to lucky

readers of Speech & Language Therapy in Practice.

To enter, simply send your name and address marked

Speech & Language Therapy in Practice - WWD offer to

Su Underhill, Speechmark, Telford Road, Bicester, OX26

4LQ. The closing date for receipt of entries is 25th January

and the winners will be notified by 31st January.

Working with Dysphagia is available, along with a

free catalogue, from Speechmark, tel. 01869 244644.

Congratulations to Angela Abell, K. McGuigan, Miss

R. Surridge and Ellen Hesketh who won

Speechmarks The Selective Mutism Resource

Manual in an Autumn 2001 reader offer.

Also to Mrs Linda Robinson, Helen E. Bruce and K.

McGuigan (again!) who won Music Factory, courtesy

of Widgit Software, an offer in the same issue.

R

E

A

D

E

R

O

l

l

E

R

R

E

A

D

E

R

O

l

l

E

R

R

E

A

D

E

R

O

l

l

E

R

Speech & Language Therapy in Practice is pleased to report that, in spite of increasing production

costs and minimal advertising revenue, subscription prices are being held yet again for 2002.

This means that:

for only 25, you have all the advantages of a personal UK subscription

UK part-timers (5 or fewer sessions) will continue to enjoy these advantages for 16 per cent less

UK students and those on a career break will continue to enjoy these advantages for 28 per cent less

UK departments and other groups, including those outside the UK, will continue to benefit from our exceptional bulk rates

everyone can continue to access our regularly updated website with online payment facility.

We work to drive up standards and keep costs low so that you benefit in every way.

Remember, the more people who subscribe to the magazine, the longer we will be able to keep subscription rates at their present low level - so why not recommend

it to a friend? They will benefit from 5 issues for the price of 4 in their first year of subscribing, and you will get an extra 3 months FREE (see back inside cover for details.)

- every ones a winner!

Inside cover

Winter 01 speechmag

Reader offer

A chance to win Working with Dysphagia from Speechmark.

2 News / Comment

4 Evaluation

Without the reflective diary and contemporaneous

records of discussions, the speech and language

therapist and the group leader would have only had

the option of feeling, Havent we done well?

(which could have occurred just because the very

large project had finally finished).

The shift away from one-to-one direct intervention

presents extra challenges when we try to

demonstrate effectiveness. Sue Dobson reports on

the value of a reflective diary for a feelings project

with adults with learning disabilities.

7 Further reading

User involvement, stroke, stammering / Parkinsons

disease, mutism, aphasia.

8 User involvement

... use of this method [a questionnaire] has the

potential to explain why some services are accepted

while others are declined, and by whom. In these

days of limited resources, it is hard to overestimate

the importance of maximising the uptake of services

provided and cooperation with therapy.

Evidence-based practice should

include evidence of the acceptabili-

ty as well as the effectiveness of

health care services. Margaret

Glogowska and colleagues found

out what parents thought of their

childs speech and language thera-

py, and how services could improve

as a result.

11 Research

report

There is clearly a need for a non

invasive, easily transportable system

which will be both well tolerated by

infants and allow objective and

simultaneous assessment of several

aspects of infant feeding.

Anthea Masarei and colleagues detail

the progress of the Great Ormond

Street Measurement of Infant Feeding (GOSMIF) which

provides objective assessment of babies fed via a bottle.

19 Reviews (cont. p24)

Voice, stammering, acquired disorders, semantics,

paediatric dysphagia, multiple sclerosis, child language,

language and literacy.

SPEECH & LANGUAGE THERAPY IN PRACTICE WINTER 2001 1

20 In my experience:

Making learning meaningful

The first time a teaching colleague asked me to get

involved in a maths lesson, I replied, Me? Me, who

struggled endlessly with maths at school? OK, so I got

a B grade at O level, but I never really totally

understood what I was doing! Now...I realise it is the

comprehension of mathematical language concepts

that gives meaning to the subject.

In a discussion which has relevance to our role whatever

the client group, Wendy Rinaldi shows how a language-

based approach to school curriculum subjects improves

collaboration with education staff and gives more

meaningful learning opportunities to children with

language impairment.

22Collaboration

By studying together with teachers, speech and language

therapists will be enabled to understand different

approaches to teaching methods and will also develop a

greater awareness of how children think and learn, while

teachers will gain a better understanding of speech, lan-

guage and communication needs and how intervention

can be used to help children overcome their difficulties.

Ruth Paradice explains what a new Joint Professional

Development Framework should mean for speech and

language therapists, teachers and children with

speech, language and communication needs.

25 How I use music in therapy

Using music in this way feels genuinely therapeutic as

it involves creating opportunities and offering time,

support and feedback. It demands

of the therapist the very

basic skill of really tuning

in and of being

fundamentally

facilitative...

Claire Finlay, Helen

Bruce and Wendy

Magee with Susan

Farrelly & Sophie

MacKenzie inspire us to

turn on, tune in and sing

out with all client groups.

Back cover

My Top

Resources

Audited benefits of

Johansen Sound Therapy

include improvements in

concentration, comprehension, reading and spelling,

and, in particular, in maximising the benefits of the

teaching and therapy they are already receiving.

Nicola Robinson and Camilla Leslie work with

children at primary and secondary school stages who

present with specific speech and language /

communication difficulties, with or without associated

difficulties with reading and spelling.

WINTER 2001

(publication date 26th November)

ISSN 1368-2105

Published by:

Avril Nicoll

33 Kinnear Square

Laurencekirk

AB30 1UL

Tel/fax 01561 377415

e-mail: avrilnicoll@speechmag.com

Production:

Fiona Reid

Fiona Reid Design

Straitbraes Farm

St. Cyrus

Montrose

Website design and maintenance:

Nick Bowles

Webcraft UK Ltd

www.webcraft.co.uk

Printing:

Manor Creative

7 & 8, Edison Road

Eastbourne

East Sussex

BN23 6PT

Editor:

Avril Nicoll RegMRCSLT

Subscriptions and advertising:

Tel / fax 01561 377415

Avril Nicoll 2001

Contents of Speech & Language

Therapy in Practice reflect the views

of the individual authors and not

necessarily the views of the publish-

er. Publication of advertisements is

not an endorsement of the adver-

tiser or product or service offered.

Any contributions may also appear

on the magazines internet site.

Contents

WINTER 2001

Cover picture by Paul Reid.

Thanks to Helen Gowland and

Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art

and Design.

See page 11.

www.speechmag.com

IN FUTURE ISSUES

PAEDIATRIC FEEDING AAC ETHICS IN DYSPHAGIA

AUTISM HEARING IMPAIRMENT CLINICAL EDUCATION

14 Expressive arts

Same people altogether - similar but different,

like being pals. The people helping too were

awfully good. That first year I wouldnt have

gone because at that time I was thinking I

would still be alright - doing a lot to try to help

myself. The worst thing was coming to, youre

not going to be the way you want - youve got

to change your heads way. Even now, its hard.

Avril Nicoll meets participants in the

Expression project, a collaborative venture in

printmaking involving people with aphasia.

She hears their unique and often surprising

stories about life, change, services, aphasia -

and speech and language therapy.

COVER STORY

Benefit

plea

A charity which supports families

who care for children with disabili-

ties and special needs is calling on

community health professionals to

help increase the uptake of benefits.

Contact a Family has found that

nearly half of all children and young

people with disabilities in the UK are

not receiving Disability Living

Allowance. The purpose of this bene-

fit - which can mean as much as

93.95 extra income a week - is to

meet the extra costs which arise

from having a disability. It is not

affected by savings and can be paid

on top of any other benefits or

income. The charity wants health

professionals in the community to

encourage parents to ring its new

helpline number to see if they are

eligible and to get a free informa-

tion pack.

Contact a Family Helpline,

freephone 0808 808 3555

(Mon-Fri, 10am-4pm);

www.cafamily.org.uk.

Conductive education

pioneer

The director of the birthplace and world centre of conductive education has died at home in Budapest.

In the late eighties, following the the BBC TV documentary Standing up for Joe, Mria Hri opened the doors

of the Peto Institute to foreign children and their families. She became a Trustee of the Foundation for

Conductive Education, the Birmingham-based national charity created specifically to bring Conductive

Education to the UK.

Conductive Education, an approach to managing children and adults with motor disorders such as cerebral

palsy, was developed in Budapest after the Second World War by Andrs Peto. Mria Hri was a medical student

who worked with Peto as an unpaid volunteer, and devoted her life to this work, increasingly as an educator

rather than a physician. After Peto died in 1967, she succeeded him as director and was chiefly responsible for

developing the role of conductors.

Andrew Sutton, Director of the Foundation for Conductive Education, said, Mria Hri grew up under

Fascism, qualified as a doctor under Socalism and steered the Institute

right through into Capitalism. She was a pragmatist and survivor. She

never married and leaves no surviving relatives. But there are now

nearly two hundred places around the world where conductors prac-

tise their craft and professional training courses in the UK, Israel,

Germany, Austria and the United States. That is her living memorial.

news

SPEECH & LANGUAGE THERAPY IN PRACTICE WINTER 2001 2

Black Sheep Press - an

apology from the editor

Black Sheep Press made two more

great Reader Offers in the Autumn

01 issue of Speech & Language

Therapy in Practice, for the CD Time

to Sing and Concepts in Pictures

material. Unfortunately, I printed the

companys old address. Mail re-direc-

tion ensured all entries arrived, but I

would like to apologise for my error

and to advise you of the new

address:

Black Sheep Press, 67 Middleton,

Cowling, Keighley, W.Yorks BD22

0DQ, tel. 01535 631346,

www.blacksheep-epress.com.

Society moves

The British Geriatric Society (specialist

medical society for health in old age) has

moved to Marjory Warren House, 31 St

Johns Square, London EC1M 4DN, tel. 020

7608 1369, www.bgs.org.uk.

Older people

misplaced and

forgotten

Older people with learning disabilities

are too frequently misplaced in nurs-

ing and residential homes for older

people which do not meet their needs.

According to research from the

Foundation for People with Learning

Disabilities, people with learning dis-

abilities are around 20 years younger

than other residents, staff have little or

no training in supporting them, and

there are few opportunities for daytime

activities, particularly outside the home.

David Thompson, GOLD (Growing

Older with Learning Disabilities) pro-

ject manager, said, Fifty per cent of

people with learning disabilities now

have the same life expectancy as the

general population, but services just

arent meeting their needs. Instead,

people find themselves cut off from

day services, with little opportunity to

maintain friendships and relationships

outside the residential home, which we

know to be a safeguard against abuse,

and often overlooked by specialist

learning disabilities services.

The research report recom-

mends a review of all place-

ments of people with learn-

ing disabilities in older peo-

ples homes by learning dis-

ability care management. It

also calls on local authorities

to hold registers of people with

learning disabilities, and services

to pay more attention to helping

maintain older peoples social net-

works and family relationships.

Misplaced and Forgotten, 10 + p&p,

Foundation for People with Learning

Disabilities, tel. 020 7535 7441, or

download it free from www.learning

disabilities.org.uk.

Disabled young people face social exclusion

Action for autism

The UKs leading autism charity intends to mark

its 40th anniversary in 2002 with its biggest cam-

paign to date.

Action for Autism will see the National Autistic

Society working to raise public awareness, taking

a lead role in encouraging integrated working

across agencies, and raising 4 million to support chil-

dren and adults with autism. Initially established in 1962 by

a small group of parents frustrated by the lack of appropriate

provision for their children, the Society provides education, care and sup-

port services for those with the disability and their families.

www.nas.org.uk

Not being listened to, having no friends, and finding

it difficult to go shopping, to the cinema or out club-

bing are some of the problems faced by disabled 15-

20 year olds.

Young disabled people interviewed for a leading dis-

ability charity also identified a lack of control over money,

feeling a burden and being harrassed and bullied as part

of their social exclusion. In a new report, Scope calls on

service providers and policy makers to tackle the issue as,

despite social exclusion being on the mainstream policy

agenda, the experience of young disabled people with

high level support needs is not generally addressed.

Richard Parnell, Head of Research and Public Policy at

Scope says, Scope wants policy and service providers

to look again at their policy and service objectives. We

want them to ensure that they go beyond the physical

and basic needs of these young people and take into

account their views and opinions on how they wish to lead

their lives if they are ever to achieve true equality.

That kind of life is 3 to individuals and aid users and 12.50

to professionals and organisations, tel. 020 7619 7341.

www.scope.org.uk.

Benchmarking

New benchmark statements for health care professions including speech

and language therapy will help in the design and review of education

and training programmes.

Covering both the academic and practice elements of health care pro-

grammes, the statements were drafted by groups including practitioners

and representatives of professional bodies. Benchmark statements repre-

sent general expectations of the attributes and capabilities that those

possessing a qualification should be able to demonstrate.

The Quality Assurance Agency for Higher Education reports that - as

work progressed on dietetics, health visiting, midwifery, nursing, occupa-

tional therapy, orthoptics, physiotherapy, podiatry, prosthetic and

orthotics, radiography and speech and language therapy - it became clear

that a common health professions framework was emerging.

http://www.qaa/ac/uk/crntwork/benchmark/nhsbenchmark/benchmarking.htm.

~

~

~

~

SPEECH & LANGUAGE THERAPY IN PRACTICE WINTER 2001 3

news & comment

A potent

combnaton

How many of us describe spending time being creative - whether through art,

music or movement - as therapeutic? In a profession so dependent on words,

turning to other methods of self-expression and communication provides

welcome relief. The actual doing enables us to say things we had previously

found difficult to put into words while, at the same time, words inform and

help us improve our creative skills.

This potent combination of expressive arts and words can be harnessed in

speech and language therapy to great effect and enjoyment for all

concerned, as is shown in How I use music in therapy (p.25) In the Expression

project (p.11) the creative process of printmaking allied with facilitated

discussion, at a time when they were ready to reflect, enabled the

participants to explore their aphasia and its implications, and describe this

verbally and non-verbally. Margaret Glogowska and colleagues (p.8) also

amply demonstrate how giving people an opportunity to reflect on services in

a way that is meaningful to them produces a wealth of information so these

services can develop in a user-friendly way. Sometimes changes needed are so

small or subtle that they can be incorporated very easily into our everyday

practice. At other times, as Anthea Masarei et al (p.17) have discovered, a

full-scale research and development project is needed.

Sue Dobson (p.4) and her key worker colleague ran a group with adults with

learning disabilities, with Sue as the speech and language therapist working

in a supportive but gradually less direct way. The key worker used a reflective

diary which proved useful for gathering qualitative information on outcomes,

and provided motivation for her to persevere. The collaborative aspect of the

approach to the group was crucial, particularly the speech and language

therapist continuing to do as well as to be involved in the reflection.

We so often want to work collaboratively but need to address this both from

a top down, strategic and a bottom up, clinical governance perspective. The

new Joint Professional Development Framework (p.22) seeks to provide an

impetus and a context for individuals to work more collaboratively but leaves

the creative detail to the individuals concerned. Wendy Rinaldi (p.20) suggests

an overall approach to working more effectively with teachers and several

ways of creating these opportunities, and this issues My Top Resources provides

some very specific practical ideas for working on language and literacy.

As loyal readers you already know that Speech & Language Therapy in

Practice values that potent combination of doing and reflecting. I am

delighted to tell you that subscription rates are again being held at their

current low level, and I look forward to your continued custom in 2002.

With best wishes for the New Year,

...comment...

Avr Nco,

Edtor

Knnear Square

laurencekrk

ABo +Ul

te/ansa/ax o++

;;(+

e-ma

avrncoQspeechmag.com

Earlybird

An innovative centre for children with autism

spectrum disorder and their families has entered

its fifth year with a new director.

Jo Stevens, who has taken over the helm of the

National Autistic Societys EarlyBird Centre, is a

teacher and licensed user of the programme

which she has been running in Lincolnshire.

The EarlyBird Centre continues to offer three

day training courses for teams of at least two pro-

fessionals wishing to become licensed users of the

programme. The centre has found this skill shar-

ing amongst teams of different disciplines and

agencies is an appropriate and effective way to

help parents cope with the pervasive effects of

autism spectrum disorder.

NAS EarlyBird Centre, 3 Victoria Crescent West,

Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S75 2AE. Tel: 01226 779218.

Technology in the community

A multidisciplinary team specialising in the assess-

ment of electronic technology for severely disabled

people is taking its service into the community.

Speech and language therapy, occupational

therapy and rehabilitation engineering staff making

up the core Compass team are from the Royal

Hospital for Neuro-disability, a national medical

charity. Assessments for communication aids,

computers, environmental controls and powered

wheelchairs for clients who require simple switches

to operate the equipment can now be carried out in

the community, nursing homes and other hospitals.

The Compass team can also draw on other services

at the Royal Hospital if extra help is needed with

setting up equipment or with support and training.

Details: Compass Project Coordinator Gary

Derwent, tel. 020 8780 4500 ext. 5237.

Speaking out about stroke

A new report shows how far health services have

to improve before they can be seen to provide a

reasonable stroke service.

Although treatment in stroke units reduces

death and disability by 25 per cent, the Stroke

Association survey found that only 22 per cent of

respondents were treated in a stroke unit. Further

difficulties arose over discharge and rehabilita-

tion arrangements.

The charity is now carrying out a survey of NHS

hospitals in England and Wales on their specialist

stroke services as the government does not collect

this information centrally. It plans to use evidence

of gaps to lobby for improvements.

Speaking Out About Stroke Services from the

Stroke Association, tel. 01604 623 933.

Implant improvements

Children receiving a cochlear implant are set to

benefit from a technique which reduces scarring,

psychological trauma and infection rates.

The Queens Medical Centre in Nottingham is

pioneering the insertion of a cochlear implant

through a small, 3cm incision behind the ear. The

childs hair can be pinned back while the opera-

tion takes place and there are no stitches to

remove afterwards.

evaluation

SPEECH & LANGUAGE THERAPY IN PRACTICE WINTER 2001 4

you want to

do ess hands-on

therapy

montor quatatve

change

share your enthusasm

or communcaton

evauaton

When

effectiveness

is hard to

prove

Changes in the way speech and language therapy

is delivered means therapists are improving their

skills in facilitating, teaching and joint working.

Although welcome, this shift away from one-to-

one direct intervention presents extra challenges

when we try to demonstrate effectiveness. Could

reflective diaries be a useful method?

Sue Dobson reports on a feelings project with

adults with learning disabilities.

here are considerably fewer speech

and language therapists employed to

work with adults with learning disabil-

ities since the closure of the larger

institutions and the advent of commu-

nity care (Dobson & Worral, 2001). This factor,

together with changes in working practices to a

more advisory / consultative role (Money, 2000),

has led to a difficulty in measuring the effective-

ness of recommended interventions.

An episode of communication intervention is

now usually delivered and led by the day-care

workers or residential staff in the community

(Purcell et al, 2000). The role of the speech and

language therapist has become more of a facilita-

tor, supporter, trainer, and joint planner of inter-

ventions rather than to deliver hands-on therapy.

This means the therapists concerned often have

difficulty in evaluating the outcomes of their

action, as they cannot control many of the vari-

ables that influence the delivery of the therapeu-

tic process. Communication is viewed in the con-

text of the perspective and influence of the com-

munication partners - staff, peers and significant

others. Interventions therefore have to focus on

influencing:

1. the staff group

2. the activity

3. how it will be organised and delivered

4. using an appropriate tool to evaluate its effect.

The programmes, therefore, do not lend them-

selves to standard evaluation packages or meth-

ods. Some detailed quantitative evaluations may

take longer than the actual delivery of the inter-

vention itself; the danger then becomes that the

programmes are rarely fully monitored or

reviewed. So, different styles of effective methods

of evaluation need to be explored.

This article concentrates on the intervention

offered to a lady with autism spectrum disorder.

The intervention, which spanned a twelvemonth

period, focused on her emotional distress and her

inability to express it in a socially acceptable way.

As a project, it included all her peers and aimed to

develop an evaluation method which would be

useful to all those participating - peers and staff.

Qualitative changes

The initial three month period of joint working

with the group of service users involved was a

matter of routine style of evaluation: joint plan-

ning of each session, end of session discussions,

and monitoring and recording of individual and

group outcomes against the stated aims and

objectives. The second stage, of monthly visits to

the group by the speech and language therapist

and generalisation of the service users skills, and

the final stage of monthly meetings and discussion

with the group leader, presented greater difficulties.

The main focus of the work - qualitative changes

in communication, social interactions and the

environment - was evaluated using a reflective

diary written after each session by the group leader.

This was supplemented by records of facilitated

Read this

T

s

e

e

w

w

w

.

s

p

e

e

c

h

m

a

g

.

c

o

m

in

s

id

e

fr

o

n

t

c

o

v

e

r

SPEECH & LANGUAGE THERAPY IN PRACTICE WINTER 2001 5

evaluation

reviews of progress during the joint monthly dis-

cussions. Reflective diaries have become a com-

mon feature in accredited courses at universities

for nurses, therapists and social workers. They can

also be used in the personal development log of

registered speech and language therapists, and

are regarded as acceptable evidence within clinical

governance activities.

Our client, R, was 29 years old with severe learn-

ing disabilities and autism spectrum disorder. A

lot of her speech was echoing commonly used

staff phrases. She was very emotionally volatile

and often became distressed about disruptions in

her routine or her inability to obtain items about

which she was currently obsessed. When this

occurred she shouted using repetitive phrases.

When extremely distressed she abused herself by

throwing herself violently on the floor or against

walls. Her general demeanour was that of

extreme anxiety. She constantly prowled around

the day centre looking for things to collect and

making excessive amounts of noise. It was diffi-

cult to engage her in activities and she rarely

interacted with her peers. It was felt her lack of

adaptability and poor level of social

competence were major factors in her

continuing distress.

Rs key worker reflected on referring

her for speech and language therapy:

Id been poorly for quite sometime

and when I returned to work, I felt Id

lost touch with my group. One of my

students was bouncing off walls and

screaming, one was shouting and

interrupting over the top of everyone.

Two of my students were always in

tears and one hid others belongings just to upset

them. Another student scratched herself and oth-

ers until they bled and the final one was very

withdrawn.

The agreed years plan was to establish a discus-

sion group which focused on emotions and creat-

ed a feelings communication book for each stu-

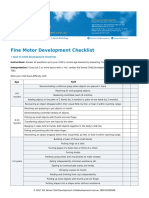

dent (sample pages in figure 1). The first months

led to the following comments by the group

leader:

For weeks we have cut out happy arms, happy

eyes, happy bodies! Weve made lists of things

which make us happy, temperature charts about

how happy we are and what we would say and

when wed say it...Its evident that its hard work for

them to see from our faces what we are feeling.

Transition

In the fourth month the therapist stopped attend-

ing every group but remained in close weekly con-

tact with the group leader for discussion. She also

supported the making of charts, symbolic material,

or social stories about situations in the centre. The

group leader was recording at this time of transi-

tion in delivery of the planned intervention:

At the beginning I felt I was preaching. Now

some of the group are beginning to think this

work applies to them. If they miss a group theyre

saying Im sorry to let you down. I was worried

about some aspects of the emotions such as cross

and that it would cause me problems but its been

a realisation. Its allowed the group to wave feel-

ings that they have had to keep quiet about. They

feel what they say is important If one of them

misses a group the others are passing on the best

of what we did to let them know too.

Individual records also showed that R had spon-

taneously approached the group to apologise for

screaming. Other group members were interrupt-

ing less frequently or volunteering comments

without prompts. One of the more withdrawn

group members was getting materials out in

preparation for the group without being asked.

The group leader felt:

This work has given the group a lot of order

which we didnt have before ... they are staying

on the section and joining in more.

There were also records about how some emo-

tions seemed to cause more difficulty than others.

Sadness had posed particular problems. However,

when R was seen to be crying two days after the

session the group leader recorded:

She was so distressed she hardly

noticed when I sat next to her. I

said, Oh dear, you are sad. Whats

the matter, love? She answered

me very quietly saying, I want my

mum. After a bit she used a much

louder voice and said, Enough

now, much better now and gave

me a cuddle and got up and left.

Some feelings, such as tired,

seemed to affect the groups imme-

diate physical behaviour. R

wrapped herself in a blanket and went to sleep

when tiredness was the topic. They found those

feelings which had clear physical symptoms easier

to describe; for example, tiredness was described

in terms of yawning, aching legs, and difficulty in

keeping your eyes open. Certain sessions were of

more relevance to some of the group. When this

happened they showed greater interest, made

more comments and participated to a higher

degree than usual. One of the group who is often

seen as lethargic described tiredness as:

If you are tired you can look ill. You may feel

cross for no reason, get in a muddle and find it

hard to talk.

Another woman, who was seen as energetic,

showed a complete lack of interest in this topic.

On the day tiredness was discussed she increased

her rate of interrupting and talked over the top

of others to a point where they objected.

Throughout this time R had always been pre-

sent, but never sat at the table with the group.

She had usually been seated in a corner of the

room. She came to the table when it was her turn

and participated but then returned to her space.

The group had started in a small but quiet room.

R had found this too confining so eventually the

group returned to the larger, key worker section

which was less private and noisier. After the

At the beginning

I felt I was

preaching. Now

some of the group

are beginning to

think this work

applies to them.

Figure 1 Sample pages from feelings communication book.

evaluation

SPEECH & LANGUAGE THERAPY IN PRACTICE WINTER 2001 6

moves, the level of discussion improved. The

leader recorded in her diary:

It was as if home ground made it easier to

discuss sensitive topics.

They send their love

Despite distancing herself from the group physi-

cally, it became clear R was listening and process-

ing what was being discussed. The leader had

noted, when being loved had been the groups

topic, that love seemed to be equated by all par-

ticipants with presents, and that most of the

group had really failed to fully understand the

concept. However, two weeks later, R forgot to

bring her home-to-centre communication book.

When the group leader expressed her disappoint-

ment at this, R offered the alternative and con-

textually appropriate reply of, They send their

love. This script had been used within the group.

Later, during the groups discussion of mischief, R

approached the table when it was not her turn in

the discussion, took the group leaders plan for

the group, screwed it up and put it in the bin. She

then said, Only kidding. The group leader was

by this time making short notes at the end of

groups such as a very productive session.

A month before the group finished, the leader

was noting R was now joining in the group on

occasions when it was not her turn. Her comments

were recorded as calm, quiet and appropriate.

The group leaders reflections indicated that R no

longer seemed threatened by the situation and

that her general manner in the centre was qui-

eter, and she was less often seen to be upset. She

reflected:

Its almost full circle now and we still need to do

anger. They have never discussed what it looks

like or how it feels and although Ive discussed

anger as a side effect of a lot of the situations

weve discussed, theyve always avoided it Some

clearly struggle to see the difference between

angry, jealous and sad I think they are scared of

showing it or talking about it They are expected

to be happy, angry isnt acceptable.

The record for the last group talked about the

need to build up trust and feel safe within the

group before being able to say anything about

anger or say what they could do to help each

other in angry situations. The last entry in the

reflective diary listed what had happened to the

service users over the year. The lady who hid other

peoples things touchingly discussed her feelings

of how she couldnt enjoy life as she wanted

because of her medical conditions. The lady who

hit and scratched herself was able to say she

wished to leave the centre and, once in control of

her anger, was able to attend another centre. The

lady who was withdrawn started to say what she

didnt like. The student who cried most of the

time told the group how lonely she was, how too

much was asked of her, and how much she liked

praise. The service user who interrupted all the

time now has an awareness of it, and she does it

less frequently and is seen as being prepared to

listen to other points of view. Finally R who, to

start with,

was bouncing off walls finds it easier to express

herself... she repeats less and has much better eye

contact. She shows her sense of humour.

Spontaneous

R was recorded as using more spontaneous utter-

ances which were longer and had a higher level of

structure; for example, Louise, Look at me,

mince pie please, when a promise had been for-

gotten. She was also using a wider range of com-

municative functions. Prior to the group, most of

her utterances had been requests for objects or

immediate needs. Some of her utterances now

also reflected the work on scripts for communica-

tion of feelings and emotions, such as, Oh my

god, its David! on seeing someone she found

frightening.

The group leader felt

running the group had

been a great learning

experience but, best of all,

I feel I understand my stu-

dents better and the issues

that are important to them.

It was truly a communication

breakthrough for every-

one.

Her initial intention had

been to use the group

work to help her complete

individual communication

profiles for the group

members. She stated that

this group had enabled

her to understand and

describe the quality of

their communication and

their needs in much greater depth. In the group

leaders evaluation of the therapy service and its

support she described that in the beginning shed

been sceptical and unsure of what the planned

group was likely to achieve. All she had initially

wanted was to create good communication pro-

files for each service user in the group. However,

the value of having someone to share both the

frustrations and the real breakthroughs with had

been important. The support of having someone

to prepare the necessary material, create the com-

munication books and record the work from an

outside perspective had been helpful. Her feeling

was that, without this kind of support, the group

would have stagnated and fizzled out. Part of the

pleasure of running it and completing the inter-

vention was the excitement of sharing what the ser-

vice users felt, their achievements and the books

they had created.

Reflective diaries are most often used as a medi-

umfor staffs personal development. It seems, how-

ever, that they can also provide useful informa-

tion about the service users development. In the

case of this group, only measuring their perfor-

mance against the aims and objectives of the

intervention plan would have left a lot of the

qualitative changes unrecorded. How, for exam-

ple, do you define a sense of fun or an aware-

ness of hurting others feelings? The group

leaders regular record keeping in the form of a

reflective learning log for herself meant it was

possible to look back and compare her impres-

sions of how much the participants understood

and applied their new knowledge. Without the

reflective diary and contemporaneous records of

discussions, the speech and language therapist

and the group leader would have only had the

option of feeling, Havent we done well?

(which could have occurred just because the very

large project had finally finished).

This method of recording change also enabled

the inclusion of Rs peers progress in a lively and

interesting format. The log includes some heart

touching insights into the

frustrations experienced by

the participants in everyday

situations and the similarity

of the kind of everyday

annoyances which affect us

all. The group leader put it

in her final entry in the log:

/ have noticed a distinct

change in my relationship

with them, We have grown

closer and more trusting of

each other, student to stu-

dent and students to me. ...

Our sameness has modified

our behaviour. Although the

groups finished I can still

hear the work coming back

to me in the scripts we

planned together.

Sue Dobson is a specialist speech and language

therapist with the clinical liaison team at Horton

Park Health Centre, 99 Horton Park Avenue,

Bradford BD7 3EG, tel. 01274 228900, e-mail dob-

son@bcht.northy.nhs.uk.

Acknowledgement

Thanks to Linda Thresher, Bradford Social Services,

for making this study possible.

References

Dobson, S. & Worrall, N. (2001) The way we were

... Bulletin of the Royal College of Speech and

Language Therapists. May 589, 7-9.

Money, D. (1997) A comparison of three

approaches to delivering a speech and language

therapy service to people with learning disabilities.

European Journal of disorders of Communication

32 (4) 446-449.

Purcell, M., McConkey, R. & Morris, I. (2000) Staff

communication with people with intellectual dis-

abilities: the impact of a work based training pro-

gramme. International Journal of Language and

Communication Disorders 35 (1) 147-158.

Do I actively seek

useful methods of

evaluating everyday

practice?

Do I make use of a

reflective diary for my

personal and

professional

development?

Do I recognise that my

support can be as

crucial to a project

continuing as it is to it

starting?

Reflections

SPEECH & LANGUAGE THERAPY IN PRACTICE WINTER 2001 7

further reading

APHASlA

Yasuda, K., Nakamura, T. & Beckman, B. (2000) Comprehension and storage of four seri-

ally presented radio news stories by mild aphasic subjects. Brain Lang 75 (3) 399-415.

The present study investigated aphasic subjects ability to comprehend and store serially

presented discourse. Sixteen mild aphasic subjects, eight age-matched normals, and eight

younger normals listened to four serially presented radio news stories and a single radio

news story. Half of the aphasic subjects performed as well as age-matched normals in a sin-

gle-news-story comprehension task. However, they demonstrated a drastic deterioration

in performance when asked to listen to a series of four news stories. Age-matched nor-

mals, and aphasic subjects, to a lesser extent, showed an impairment in the comprehen-

sion and storage of the news story heard last in a series of four news stories. These results

were discussed in terms of the comprehension and storage resources of working memory.

lURTHER

READlNG

Ths reguar eature

ams to provde

normaton about

artces n other

journas whch may

be o nterest to

readers. The Edtor

has seected these

summares rom a

Speech 8 language

Database comped

by Bomedca

Research lndexng.

Every artce n

over thrty journas

s abstracted or

ths database,

suppemented by a

monthy scan o

Nedne to pck out

reevant artces

rom others.

To subscrbe to the

lndex to Recent

lterature on

Speech 8

language contact

hrstopher Norrs,

Downe, Badersby,

Thrsk, North

Yorkshre YO; (PP,

te. o+; (o8,

ax o+; (o.

Annua rates are

Ds (or vndows

,):

lnsttuton L,o

lndvdua Lo

Prnted verson:

lnsttuton Lo

lndvdua L(.

heques are

payabe to

Bomedca

Research lndexng.

u

r

t

h

e

r

r

e

a

d

n

g

u

r

t

h

e

r

r

e

a

d

n

g

u

r

t

h

e

r

r

e

a

d

n

g

u

r

t

h

e

r

r

e

a

d

n

g

USER lNVOlVENENT

Dixon-Woods, M. (2001) Writing wrongs?

An analysis of published discourses

about the use of patient information

leaflets. Soc Sci Med 52 (9) 1417-32.

Much has been written about how to com-

municate with patients, but there has been

little critical scrutiny of this literature. This

paper presents an analysis of publications

about the use of patient information

leaflets. It suggests that two discourses can

be distinguished in this literature. The first

of these is the larger of the two. It reflects

traditional biomedical concerns and it

invokes a mechanistic model of communica-

tion in which patients are characterised as pas-

sive and open to manipulation in the interests

of a biomedical agenda. The persistence of the

biomedical model in this discourse is contrast-

ed with the second discourse, which is smaller

and more recent in origin. This second dis-

course draws on a political agenda of patient

empowerment, and reflects this in its choice of

outcomes of interest, its concern with the use

of leaflets as a means of democratisation, and

its orientation towards patients. It is suggested

that the two discourses, though distinct, are

not entirely discrete, and may begin to draw

closer as they begin to draw on a wider set of

resources, including sociological research and

theory, to develop a rigorous theoretically

grounded approach to patient information

leaflets. (141 References)

NUTlSN

Gordon, N. (2001) Mutism: elective or selective, and acquired. Brain Dev 23 (2) 83-7.

When a child does not speak, this may be because there is no wish to do so (elective

or selective mutism), or the result of lesions in the brain, particularly in the posterior

fossa. The characteristics of the former children are described, especially their shyness;

and it is emphasized that mild forms are quite common and a definitive diagnosis

should only be made if the condition is significantly affecting the child and family.

In the case of mutism due to organic causes, the commonest of these is trauma to

the cerebellum. Operations on the cerebellum to remove tumours can be followed

by mutism, often after an interval of a few days, and it may last for several months

or longer, to be followed by dysarthria. Other rarer causes are discussed, and also

the differential diagnosis. The so-called posterior fossa syndrome consists of mutism

combined with ataxia, cranial nerve palsies, bulbar palsies, hemiparesis, cognitive

impairment and emotional lability, but the post-operative symptoms are often dom-

inated by the lack of speech. The most accepted cause for the condition is vascular

spasm with involvement of the dentate nucleus and the dentatorubrothalamic tracts

to the brain-stem, and subsequently to the cortex. Diaschisis may be involved in

causing the loss of higher cerebral functions, and possibly, complicating hydro-

cephalus. The treatment of elective mutism is reviewed, either using a psychotherapeutic

approach or a variety of drugs, or both. These may well be ineffective, and it must

be remembered that the condition often resolves on its own. The former treatment

must concentrate on the training of social skills and activities of daily life and must

be targeted to both the child, the family, and the school. Also, all kinds of punishment

and insistence on speech must be discouraged. The drug, which seems to be most

effective, is fluoxetine. Discovering more about the causes of mutism due to organic

causes may well depend on studies using such techniques as magnetic resonance

imaging and single photon emission tomography. (42 References)

STROKE

Sundin, K., Norberg, A. & Jansson, L. (2001)

The meaning of skilled care providers

relationships with stroke and aphasia

patients. Qual Health Res 11 (3) 308-21.

Little is known about the reciprocal influ-

ence of communication difficulties on the

care relationship. To illuminate care

providers lived experiences of relationships

with stroke and aphasia patients, narrative

interviews were conducted with providers

particularly successful at communicating

with patients. A phenomenological

hermeneutic analysis of the narratives

revealed three themes: Calling forth

responsibility through fragility, restoring

the patients dignity, and being in a state of

understanding. The analysis disclosed car-

ing with regard to the patients desire,

which has its starting point in intersubjec-

tive relationship and interplay, in which

nonverbal communication is essentialthat

is, open participation while meeting the

patient as a presence. Thus, care providers

prepare for deep fellowship, or commu-

nion, by being available. They described an

equality with patients, interpreted as fra-

ternity and reciprocity, that is a necessary

element in presence as communion. The

works of Marcel, Hegel, Stern, and Ricoeur

provided the theoretical framework for the

interpretation.

STANNERlNG / PARKlNSONS DlSEASE

Shahed, J. & Jankovic, J. (2001) Re-emergence of childhood stuttering in

Parkinsons disease: a hypothesis. Mov Disord 16 (1) 114-8.

OBJECTIVE: To characterize speech patterns in patients with Parkinsons disease (PD) who

have a history of childhood stuttering. BACKGROUND: Childhood stuttering usually

resolves, but it re-emerges in some patients after stroke or other brain disorders. This phe-

nomenon of recurrent stuttering has not been characterized in childhood stutterers who

later develop PD. METHODS/PATIENTS: Twelve patients with a history of childhood stut-

tering that remitted and subsequently recurred were included in the study. A structured

interview was administered to seven patients, and six were able to answer questions

about childhood stuttering. The Johnson Severity Scale (JSS) (range 0-7) and a Situation

Avoidance Scale (SAS) were used to rate stuttering severity (range 0-15) and avoidance

(range 0-15). RESULTS: The mean age at onset of childhood stuttering was 6.2 years (range

5-10), the mean latency from the onset of childhood stuttering to adult stuttering was

46.1 years, and the stuttering recurred on average 5.9 years (range 0-21) after the onset

of PD. The stuttering characteristics in childhood and adulthood included repetitions of

sounds and syllables at the beginnings of words, blocks and interjections, physical tension,

and a worsening of symptoms with stress. The patients rated themselves as having mild-

to-moderate childhood stuttering by the JSS (mean 3.0, range 2-4) and mild-to-moderate

stuttering and avoidance by the SAS (mean stuttering score 5.3, range 3-7, mean avoid-

ance score 4.2, range 3-6). There was no apparent association between the severity of

childhood stuttering and the severity of PD, but those patients who had higher Unified

Parkinsons Disease Rating Scale scores tended to have more and worse symptoms of stut-

tering. CONCLUSION: Our patients provide evidence for the hypothesis that childhood

stuttering may re-emerge in adulthood with the onset of PD. (45 References)

user involvement

SPEECH & LANGUAGE THERAPY IN PRACTICE WINTER 2001 8

he need to involve clients in health

care decisions and the evaluation of

services is now widely acknowledged.

In recent years the participation of

parents in their childrens speech and

language therapy has increased. There has, how-

ever, been little attempt to investigate parents

opinions of the services they receive.

There have been some attempts to use clients

perceptions as a measure for audit (van der Gaag

et al, 1993; van der Gaag et al, 1998), but formal

measures of consumer satisfaction have rarely

been built into research designs evaluating treat-

ments for early speech and language delays.

When a randomised controlled trial to evaluate

the effectiveness of community-based speech and

language therapy for speech/language delayed

preschool children (described in Roulstone et al,

1999; Glogowska et al, 2000) was initiated, a

questionnaire was designed to investigate

parental views of the interventions. We hoped

that, by improving our understanding of why dif-

ferent people choose to accept or decline therapy,

we could gather ideas for planning services and

approaching parents in a way that would max-

imise uptake and cooperation.

The questionnaire was aimed at the parents of

159 pre-school speech/language delayed children

who participated in the randomised controlled

trial. The children were initially randomised to

receive either immediate treatment (Therapy

Now) or to watchful waiting for a period of 12

months before receiving therapy (Therapy Later).

The Therapy Now children received the same

intervention that would have been available to

them outside the trial. The parents of the Therapy

Later children were given general advice only but

could start receiving treatment for their children

at any point over the 12 month period if they

wished. All the children in the trial were re-

assessed at 6 months and 12 months post-ran-

domisation. The questionnaire was administered

at the 12 month re-assessment point, when the

childrens involvement in the trial ended.

Altogether, 147 parents participated in the survey

- a response rate of 92.5 per cent.

T

Evidence

based practice:

seeking the whole truth

Convenient

In the questionnaire, parents were asked to

respond to closed questions about organisational

aspects of the service. Open questions were also

included where parents could raise their own

issues. With regard to the location of appoint-

ments, usually the local community clinic, 140 par-

ents (95 per cent) found it convenient. However,

attendance was difficult for some, especially

when parents relied on public transport.

Appointment times were acceptable, with 133

parents (90 per cent) rating them as convenient.

However, in the open sections of the question-

naire, parents mentioned difficulties in attending

when they worked full-time. The time allowed for

the appointments was considered satisfactory,

with 126 parents (86 per cent) rating the length of

appointments as about right. (Routine data

available from the speech and language therapy

services being evaluated in the trial showed that

the length of sessions ranged from thirty minutes

to one-and-a-half hours). However, some parents

(4 per cent) considered the length of the appoint-

ment too long, particularly where the childs con-

centration span was short.

Parents were asked about the number of

appointments they had received. While 96 par-

ents (65 per cent) said the number of appoint-

ments was about right, 32 parents (22 per cent)

said they had received too few. Likewise, when

questioned on the gap between appointments,

103 parents (70 per cent) said the gap was about

right but 27 parents (18 per cent) said it was too

long. The responses of Therapy Now and Therapy

Later parents were compared in these areas but

no difference was found between the groups.

Routine data collected from the speech and lan-

guage therapy services involved showed that, on

average, Therapy Now children attended 7.7

appointments (the range was 0 to 17) during their

involvement in the trial and, on average, were

seen monthly (the range was from once weekly to

once every two months). Post-randomisation,

Therapy Later children were seen for re-assess-

ment after six months and for final re-assessment

after a further six months. The number and fre-

quency of appointments were major differences

between them. However, this suggested that,

even where children received intervention, par-

ents still did not feel that the amount of speech

and language therapy provision was adequate.

In the questionnaire, 130 parents (88 per cent)

responded that the therapist had given them an

explanation of their childs difficulty which was

helpful and 128 parents (87 per cent) felt that the

therapists understanding of the childs difficulties

had been good. Also, 132 parents (90 per cent)

found the therapists advice helpful and 135 par-

ents (92 per cent) said they were able to make use

of the advice. The open question on the question-

naire, What has the speech and language thera-

pist done? prompted a wide range of positive

responses from parents of both Therapy Now and

Therapy Later children, including helped the childs

talking, improved their confidence, given parents

guidance about helping, given parents reassurance

and increased parents understanding of the childs

difficulty. A few parents, again of both Therapy

Now and Therapy Later children, did not feel that

the therapist had done anything to help.

Feeling better

Parents were asked whether speech and language

therapy had made them feel better about their

child, themselves and the difficulties experienced

by the child. While 100 parents reported that

speech and language therapy had made them

feel better about their childs difficulties (68 per

cent), 50 parents reported that speech and lan-

guage therapy had made them feel better about

the child (34 per cent) and 27 parents reported

that speech and language therapy had made

them feel better about themselves (18 per cent).

Parents could give negative responses to the

above statements too, although few did. Parents

were also asked about how the child and the fam-

ily had coped with the communication difficulty

over the period of their involvement in the trial.

Broadly, parents of children in both groups

answered that the child and the family had coped

well with any difficulties and that positive

changes in the childs relating to others had

s

e

e

w

w

w

.

s

p

e

e

c

h

m

a

g

.

c

o

m

in

s

id

e

fr

o

n

t

c

o

v

e

r

SPEECH & LANGUAGE THERAPY IN PRACTICE WINTER 2001 9

user involvement

Are you frustrated when people fail to attend

or seem ambivalent about their childs therapy?

As Margaret Glogowska and colleagues

discovered, better communication between

therapists and parents and more flexible services

could make a difference.

occurred.

Parents were questioned about their views on

changes in their childrens difficulties over the

course of the year. For 139 parents (95 per cent)

there had been improvement in their childs diffi-

culty, with five parents responding that the diffi-

culty had stayed the same or got worse. Of those

parents who felt that there had been positive

change in their child, 104 parents (71 per cent)

felt that speech and language therapy provision

had contributed to the change. All the parents

were also questioned about their perceptions of

the childs need for further therapy, with 103 par-

ents (70 per cent) feeling that their child contin-

ued to be in need of therapy.

The questionnaire showed that both interven-

tion strategies were acceptable to differing sets of

parents. Many of the Therapy Now parents (96

per cent) were happy with the help they had

received and attributed their childrens improve-

ment to the treatment: Made a great difference

with his speech as he can now use short sen-

tences; Improved my sons speech and put my

mind at rest. Some parents (56 per cent) of the

children who had waited for therapy had found

the monitoring condition satisfactory: I wasnt

terribly concerned so I wasnt too worried about

waiting; I didnt mind as I wanted to see how

my child developed on his own; It gave us

chance to use the advice given to help him. For

some parents, Therapy Later was the intervention

strategy they would have chosen for themselves.

This was particularly true where the family was

experiencing difficult circumstances. For example,

one mother found it increasingly difficult to bring

her child for regular therapy, as she was also car-

ing for a terminally ill relative at the time.

Another mother explained that postponing her

childs therapy would have made life easier for her

as she was heavily pregnant with a second child,

had no car and found using public transport to

attend clinic very inconvenient.

Therapy Later was not universally acceptable,

however, as these comments show: I thought he

was not talking as well as he should; We felt he

was falling behind because of his ability to com-

municate with other children; I was concerned

about him starting school. When asked what

immediate therapy could have done, 46 parents

(71 per cent) of Therapy Later children felt that it

would have helped the difficulty. When asked

how having therapy straightaway

would have made them feel, 33 par-

ents (51 per cent) reported that it

would have made them worry less

about their childs difficulty.

However, a further 20 parents (31

per cent) felt that therapy would

have made no difference to their

concerns and 3 parents (5 per cent)

felt that therapy would have caused

them to worry more about their

childs difficulty.

Helpful

When asked about the games and activities pro-

vided in therapy, 71 parents (87 per cent of those

who received intervention) rated them as good.

Likewise, rating the strategies given them during

the therapy sessions, 68 parents (83 per cent)

found them to be good. A number of parents

made comments in the questionnaire about these

aspects: I was provided with lots of pictures and

given advice of games to play; The games and

activities that we did with her were very helpful.

When questioned about what aspects of the ser-

vice they were particularly happy with, several

parents singled out treatment activities and being

able to carry these on outside the clinic: General

advice and worksheets given in order to work

with at home; The way I was able to encourage

him at home with our sheets we were given.

However, not all parents perceived the activities

as constructive and helpful - the most common

negative perception of parents was that they

wished something more specific could have been

worked on: I felt I was guided by the speech

therapist on what to or not to do with him. I

would have liked tasks to be more specific, ie.

work on this group of words and well see how he

has got on with them next time; No answers for

the problems. Never felt it was very positive or

reassuring. Thought it would be more construc-

tive than assessments. A number of parents

expressed dissatisfaction over the lack of informa-

tion given to them about what they could do with

their child at home: The guidance was long-

winded and applicable ideas were

few; Games/activities were very lim-

ited. I would have benefited from a

few more suggestions.

Overall, parents expressed positive

views about the organisation of the

services they received. Parents them-

selves often seemed to benefit from

the provision offered because they felt

something was being done and that

their concerns about their childs

development were being taken seri-

ously. They had the opportunity to dis-

cuss the emotional aspects of having a

child with a communication difficulty and receive

support. Also, they felt they were being given the

means to help the child themselves.

The questionnaire, however, revealed areas of

difficulty for parents which might affect their sat-

isfaction with the service and even influence

whether they were prepared to attend therapy.

These included practical difficulties with getting

to clinic, the need for flexibility in arranging

appointment times, and the parents desire for

more frequent appointments. Greater awareness

of these on the part of speech and language ther-

apist and providing the opportunity for parents to

discuss these issues with the therapist might help

to increase parental adherence to therapy.

The acceptability of watchful waiting to cer-

tain parents is also of importance for speech and

language therapists. The acceptability of defer-

ring treatment to some parents will come as little

surprise to therapists. They may well have encoun-

tered families who do not cooperate with therapy

offered because they do not appreciate the sever-

ity of their childs difficulties, or because they find

it difficult to organise their lives. On the other

hand, therapists may feel disappointed and

threatened by parents who, aware of the degree

of their childs problems, are not persuaded that

They had the

opportunity to

discuss the

emotional aspects

of having a child

with a

communication

difficulty

you want to

take account o users

vews

encourage uptake o

your servce

target mted resources

Read this

user involvement

SPEECH & LANGUAGE THERAPY IN PRACTICE WINTER 2001 10

therapy should be undertaken and prefer a

watchful waiting option.

Need for discussion

The questionnaire demonstrated that, even

where parents felt immediate therapy might help,

it was not always the intervention strategy of

their choice and would not have necessarily alle-

viated their concerns. However,

the choice to delay therapy

became more explicable in the

light of the explanations dis-

closed by parents on the ques-

tionnaire. This highlights the

need for discussion with parents

about what other events may be

currently happening or about to

happen in their lives which may

interfere with regular atten-

dance at the clinic and make

speech and language therapy

seem less of a priority in their eyes. Taking into

account family circumstances should help the par-

ent and therapists to determine the best course of

action, weighing up the needs of the child and the

rest of the family in a realistic and manageable

way. Even where a parent attends clinic regularly

and willingly, it should not be taken for granted

that the family is not under severe stress.

The comments of some of the parents revealed

a large perceptual gap between them and the

therapists they saw in the area of treatment activ-

ities. One parent perceived that the play activities

undertaken by the therapist with her child were

merely ongoing assessment and therefore did not

constitute treatment for her childs difficulties.

Clearly, what the therapist aimed to achieve was

not transparent to the parent. This highlights the

need for therapists to make explicit to parents the

therapy they give. Others complained of the lack

of specific, applicable ideas. They sometimes felt

that the ideas passed on to them by therapists

were common sense or what they were already

doing with their children, to no noticeable effect.

For this reason, a check from the therapist to find

out what parents were already doing to try to

help their child, what ideas they had gleaned

from books, magazines or other media, or what

advice they had already received from friends,

family and professionals might have avoided this.

The trend towards evidence-based practice calls

for evidence of the acceptability as well as the

effectiveness of health care services. The study

reported here investigated parents response to

speech and language therapy provision for their

children alongside a trial of the clinical effective-

ness of the intervention. While the randomised

controlled trial provided information about the

progress of the children in Therapy Now and

Therapy Later, the questionnaire was designed to

show the limitations and advantages of the two

intervention strategies and to investigate other

aspects of the service from the viewpoint

of the parents whose children participat-

ed.

As a means of evaluating the accept-

ability of speech and language therapy

services, the questionnaire should be

regarded in speech and language thera-

py as a valuable tool. As this report

demonstrates, use of this method has

the potential to explain why some ser-

vices are accepted while others are

declined, and by whom. In these days of

limited resources, it is hard to overesti-

mate the importance of maximising the uptake of

services provided and cooperation with therapy.

Margaret Glogowska and Sue Roulstone are

speech and language therapists at the Speech and

Language Therapy Research Unit, Frenchay

Hospital in Bristol. Rona Campbell and Tim J. Peters

are based in the Department of Social Medicine at

the University of Bristol. Pam Enderby is at the

School of Health and Related Research in Sheffield.

References

Glogowska, M., Roulstone, S., Enderby, P., &

Peters, T.J. (2000) Randomised controlled trial of

community-based speech and language therapy

for pre-school children. BMJ 321: 923-926.

Roulstone, S., Glogowska, M., Enderby, P. & Peters,

T. (1999) Issues to consider in the evaluation of

speech and language therapy for pre-school chil-

dren. Child: Care, Health and Development 25(1),

141-155.

van der Gaag, A., Glass, K. & Reid, D. (1993) Audit:

A manual for speech and language therapists.

London: College of Speech and Language

Therapists.

van der Gaag, A., McCartan, P., McDade, A. &

Reid, D. (1998) An audit tool for health visitors

and speech and language therapists working with

the pre-school population. Proceedings of the

Royal College of Speech and Language Therapists

Conference, International Journal of Language

and Communication Disorders, 33: 37-41.

1. Find out family circumstances and priorities.

2. Check what carers are already doing to help.

3. Discuss pros and cons of starting or delaying intervention.

4. Offer advice that is as specific as possible.

5. Make sure people understand what you are doing and why at every stage.

Five steps to better practice

Taking into

account family

circumstances

should help the

parent and

therapists to

determine the

best course of

action

Career initiatives

A pioneering cadet scheme is opening up a career

in speech and language therapy to more people

from black and minority ethnic backgrounds.

The Birmingham programme offers a new way

into the profession for people who may not

have followed a traditional route through edu-

cation, but understand the language and cul-

ture of the diverse communities living there.

The cadets, supported and mentored by quali-

fied speech and language therapists, start by

obtaining a Btec in speech and language thera-

py, an NVQ in therapy skill and higher level

study skills, before going on to the three year

speech and language therapy graduate course

at the University of Central England.

The cadet scheme is funded by the West Midlands