Cross Road Blues by Robert Johnson

Diunggah oleh

Bettinamae Ordiales De MesaHak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Cross Road Blues by Robert Johnson

Diunggah oleh

Bettinamae Ordiales De MesaHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

De Mesa 1

Bettina De Mesa Eiland English103 (H) September 24, 2012 Crossroad Blues Unlike the slowly growing urban metropolises of the 1930s, the Depression era south possessed a provincial perspective towards the treatment of African Americans. In observation of that period, Mississippian Robert Johnson demonstrated his ability as a songwriter to portray the African American injustice prevalent in the south while simultaneously cementing his notoriety. Through the use of various critical perspectives, Johnsons Cross Road Blues ultimately shows the injustices and unwarranted human desires that people were prone to possessing in the 1930s. Dissecting Johnsons Crossroad Blues through a historical eye emphasizes the discri mination and societal injustice towards African Americans rooted in the stanzas of the lyrics. At the end of the Civil War, African Americans slowly garnered power through means of literacy, enfranchisement and a galvanizing political clout. With a deep seated fear embedded in African Americans to their white counterparts, the civil rights movement moved at a lethargic pace. The protagonist in the song trying to flag a ride (Johnson 4-5) before the night fell is referencing the sun down laws that were in effect during the 1930s, which restricted African Americans from being outdoors once darkness came about. These discriminatory rules inconvenienced the Black community to an insurmountable degree as many of them found difficulty in gaining transportation. Stemming from the memoirs of writer Patricia Adams, she recalled her activist mother stating that if blacks were not out of town before sundown, they were harassed by the police, and sometimes they were picked up and dropped at the city limits. Some of them lost their jobs (Adams). Johnson then introduced this aspect of social discrimination through the line

De Mesa 2

didn't nobody seem to know me, babe, everybody pass me by (Johnson 6) assumingly ascribing to the white bus drivers who preferred to ignore black travelers (Sugrue). Referring back to Patricia Adams narrative, she could recall an event where working class Black maids were purposefully overlooked by a white bus driver: The bus driver was driving as though he was in a hurry. When we got to the Rossmoyne district, the bus driver sped up even more, passing the first bus stop. A Black maid was left standing on the curb two elderly Black maids were standing on the curb, waiting for the bus. The bus driver wasn't slowing down. (Adams) From Adams personal anecdote, it is evident that blacks needed to follow these rules to in a strict manner in order to maintain the peaceful co-existence that they resided in. However, most blacks at that time were too poor to pay for transportation and relied heavily on switching freight trains and hitching rides (Weingroff). In short, if you were a nonwhite motorist you were expected to stay in your place as a second-class citizen. The etiquette says, when on wheels, do as you would on foot (Kennedy). In further elaboration, it has been shown that a black man living in Mississippi at that time had to encounter the fear of lynching and arbitrary violence every day. He alluded to this aforementioned fear in the line, you can run, you can run, tell my friend Willie Brown (Johnson 10-11) as a cry for help since night fall is soon approaching, leaving him with a greater likelihood of being beaten. Within the Deep South, lynching proved to be a common occurrence as its participants truly believed that blacks were beginning to gain too much freedom. In Trudier Harris study of burning rituals, she had concluded that Lynching was equated with guilt and punishment ensued to restore the threatened white society to its former status of superiority. The punishments, according to the black writers, become a way in which whites consolidate themselves against all possible encroachments upon their territory by blacks. (Harris 6)

De Mesa 3

To preserve the solemnity of the ritual, when the slave finally died, women drank the warm blood; the body was cut up and roasted, and the most distinguished members of the community received "delicacies" such as fingers or the fat around the liver or heart(Parker). The act itself bonded the predominantly Christian Southerners who felt that they must have committed some great sin for that bunch of feckless, effete Northerners to defeat them, casting out the blacks to symbolically cast out sin (Parker). When the sun sets, the ritual of the hunt begins, explaining the fear that Johnson exemplified in the lines standin' at the crossroad, baby, risin' sun goin' downAnd I went to the crossroad, mama, I looked east and west (Johnson 13-14) portraying his growing awareness to the surrounding dangers within the environment. Since the Jim Crow laws stated that blacks could not leave their homes after 10 p.m., the sun goin down (Johnson 14) demonstrates the anxiety of the sun setting due to the fact that for each hour he does not find transportation before the curfew, hes putting himself at greater risk for death (Packard). Using a historical perspective, it is shown that these symbolic rituals were everyday occurrences to African Americans in the South, accenting the civil rights issues that were gravely ignored at the time. Analyzing this song through a biographical perspective demonstrates the notoriety that Johnson gained by weaving myth and reality into an obscure folklore stating his negotiation with the devil. Most blacks, including Johnson, were limited to working on plantations and other agricultural jobs (Schuster). After working at the sharecropping fields, Johnson relaxed at juke joints, entertainment made for dancing, which popularized the ragtime beat that became well associated with the blues. Within those clubs, great artists like Charley Patton, Son House, and Willie Brown had made appearances to play guitar at the Saturday Night Balls. Enamored by the playing styles of Patton, Johnson began following the musicians in the late 1920s. Johnson had referenced his friendship with Willie Brown through the line you can run, you can run, tell my friend Willie Brown (Johnson 12-13) representing the closeness between the mentor-student relationship they had formed while performing together. One of Johnsons close mentors, Son House recounted of when hed slip off and come over to where we wereand sit downand watch (Rucker). Browns influence on Johnson had greatly impacted his musical styles and

De Mesa 4

teachings that Johnson he had referred to him in the song as an immediate source for help. Johnson had a propensity towards traveling from one area to another, as to escape the hardships of plantation life. Shown by the lyrics tried to flag a ride (Johnson 3-4) Johnsons penchant for the vagabond lifestyle had kept him enthralled by the thrill of wandering. According to his companion, Johnny Shines, the lauded blues musician, said Johnson would just pick up and walk off and leave you standing there playing. And you wouldn't see Robert no more maybe in two or three weeks.... So Robert and I, we began journeying off. I was just, matter of fact, tagging along (Bianco 3-5). In an interview with Jas Obrecht, Shines had stated that in order to gain money traveling they would: Work in the streets. Id go over here and start playing, and hed go over there and start playing. Hed draw his gang; Id draw mine Just try to find out where the black neighborhood was. Whichever side we find the black kids on, thats the side we go, cause that was the black side. (Johnny Shines: The Complete Living Blues Interview) It was his constant traveling that kept him from developing a relationship with his son, Claude Johnson. In a 1997 interview, the acclaimed blues singers son recalled his grandparents remarks about Johnson: They told my daddy they didn't want no part of him. They said he was working for the devil. I stood in the door, and he stood on the ground, and that is as close as I ever got to him. He wandered off, and I never saw him again. (Bragg) In analyzing Johnsons work, its apparent that his wanderlust and propensity for music had led him living a secluded and isolated lifestyle that made him into a blues legend. Adopting an archetypal perspective towards Cross Road Blues, the main protagonist in Johnsons lyrics relates closely to the representation of the shadow figure. According to Jung, most individuals are naturally disconnected from their true self, harboring a mask to correspond within the standards of society. The shadow is the dissociated second personality of a character which represents their impulses, taboo desires and unfulfilled aspirations (Fraim). Paralleled to the reality of natural human

De Mesa 5

psyches, this classification tends to show the rambunctiousness and impulsivity that most humans are eager to possess, but are unwilling to admit (Young). Unfortunately there can be no doubt that man is, on the whole, less good than he imagines himself or wants to be. Everyone carries a shadow, and the less it is embodied in the individual's conscious life, the blacker and denser it is. If inferiority is conscious, one always has a chance to correct it. Furthermore, it is constantly in contact with other interests, so that it is continually subjected to modifications. But if it is repressed and isolated from consciousness, it never gets corrected. (Jung) This archetype embodies the characters true wants within him and the ideals of society. The persona within the character is divided, with one side pleading for forgiveness and the other contemplating on his Faustian deal. The protagonist described in the lyrics went to the crossroad (Johnson 1-2), a path that most individuals encounter at some point of their lives. It marks the pivotal moment where a conflicting decision needs to be made. This perpendicular road could be seen as a visual cross. The horizontal axis marking the representation of the visual world similar to most individuals faade while the vertical axes demonstrates the unknown and mysterious, concurrent with the shadow archetype. The point where these paths meet facilitates the symbol of neutrality, where our unconscious desires and our mask intersect. With reference to the aforementioned path, the protagonist in the lyrics fell down on [his] knees (Johnson 1-2), representing his surrender to the desires of his shadow and the temptations of the devil. Soon after, the symbolism of darkness appears with risin sun goin down (Johnson 7-9). Either way, darkness is frequently associated with negative emotions fear, hatred, anger, pain, etc. As probably the most Primal Fear in the human psyche, don't expect darkness to be pleasant, even when it's not actively malevolent. (Anatomy of a Soul) Not only is a shadow formed by the contrast of shade and light, the darkness associated with it dates back to the most primitive fears of the human psyche such as anger, confusion as well as countless others. The

De Mesa 6

connection between shadows and darkness are intertwined as both are uncharted territories in an individuals psyche. Rather than diminishing the importance of the shadow it could be used to gain valuable personal knowledge, untapped by previous suppressions. However, the character mentioned in the lyrics had resorted to grieving over his loss of persona over the gain of catharsis through revealing his true desires. With further elaboration on the archetypal perspective, it is evident that the characters negotiation with the Devil asserts his descent from Gods good graces. This fall is characterized with the decline of ones being, from a higher to a lower state, usually involving spiritual corruption or dissolution of innocence. The role of the devil is useful as the character must divide the conscience against good and evil, to later reach the state of heightened knowledge. It involves an experience that changes a persons outlook and way of thinking. Jung viewed that: The fall is the necessary and unavoidable consequence of the evolution of the psyche, basically a positive process to acknowledge horror for the evil of ones sins in general and achieve enlightenment. (Becker 115) Within Cross Road Blues it is apparent that the character has already fallen into the depths of evil as he states I went to the cross road, fell down to my knees (Johnson 1-2) in order to appeal to Gods forgiving nature. As the religious expression of the unconscious, the Lord represents the force or reason and its ideal of perfection and fulfillment (Becker 116). In contrast, the first son of God, Lucifer, must show the dark, amoral cause of nature, energy, drives and evolution through division and conflict (Becker 116). In short, the characters slippage in morality had incited for a redefinition of ones self, similar to many aspects of the human persona. He is pleading with the lord to have mercy, now save poor Bob, if you please (Johnson 3). His naivet towards his actions had disappeared, although it appeared to be futile as his soul had already been sinkin' down (Johnson 9), signifying that his search for enlightenment and redemption had failed.

De Mesa 7

Through the medium of music, Johnson was able to create a composition that portrayed the inequality that African Americans faced in that particular era. Johnson simultaneously garnered a reputation of being the original creator of the blues, often being lauded by acclaimed musicians such as Eric Clapton and Keith Richards. The speculation over Johnsons deal with the devil had incited the Faustian bargain motif within the Blues and Rock and Roll Industry. The message that this song brings is effective in fueling Johnsons story, but also speaks out for the average African American.

De Mesa 8

Works Cited Adams, Patricia. "The Sundown Laws of the 1930's." Broowaha.com. Broowaha, Feb.-Mar. 2012. Web. 20 Oct. 2012. "Anatomy of the Soul." Casting a Shadow. TV Tropes, n.d. Web. 02 Oct. 2012. Armour, Steve. "British Rednerings of American Blues." Thesis. Georgia College State Univarsity, 2010. Print. Becker, Ken. Unlikely Companions: C.G. Jung on Spritual Exercise. Vol. 1. N.p.: Gracewing, 2001. Print. Bianco, David. "Artist Biography: Robert Johnson." On Line. World Wide Web. Bragg, Rick. "Court Rules Father of the Blues Has a Son." The New York Times. The New York Times, 17 June 2000. Web. 02 Oct. 2012. DiGiacomo, Frank. "Searching for Robert Johnson." VanityFair.com. Vanity Fair, Nov.-Dec. 2008. Web. 02 Oct. 2012. Fraim, John. "Jungian Theories." Symbolism.Org: Symbolism of Place: 2. Natural Places. Great House Company, n.d. Web. 27 Sept. 2012. Grazian, David. Blue Chicago: The Search for Authenticity in Urban Blues Clubs. Chicago: University of Chicago, 2003. Print. "Growing Up Black in the 1930s." Interview by Claudia D. Johnson. ThinkQuest. Oracle Foundation, 1993. Web. 26 Sept. 2012. Harris, Trudier. "Exorcising Blackness: Historical and Literary Lynching and Burning Rituals." Google Books. India University Press, n.d. Web. 24 Sept. 2012. "Johnny Shines: The Complete Living Blues Interview." Interview by Jas Obrecht. Johnny Shines: The Complete Living Blues Interview. Jasobrecht.com, n.d. Web. 24 Oct. 2012.

De Mesa 9

Johnson, Robert. "Cross Road Blues Lyrics." Cross Road Blues Lyrics. STLyrics, n.d. Web. 27 Sept. 2012. Jung, Carl. "Psychology and Religion." Jung: On The Shadow. Psychology and Religion, 1938. Web. 02 Oct. 2012. Kennedy, Stetson. Jim Crow Guide to the U.S.A.: The Laws, Customs and Etiquette Governing the Conduct of Nonwhites and Other Minorities as Second-class Citizens. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama, 2011. Print. Lawson, R. A. Jim Crow's Counterculture: The Blues and Black Southerners, 1890-1945. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State UP, 2010. Print. Packard, Jerrard. "A Brief History of Jim Crow." Constitutional Rights Foundation. Constitutional Rights Foundation, 2002. Web. 02 Oct. 2012. Parker, Susan G. "Right Now - Lynching as Human Sacrifice, November-December 1996." Right Now Lynching as Human Sacrifice, November-December 1996. Harvard Magazine, 1996. Web. 26 Sept. 2012. Rucker, James. Robert Johnson and the Roots of the Delta Blues. Rep. Rhonda Hucker, n.d. Web. Sept.Oct. 2012. Sugrue, Thomas J. "Driving While Black:"Drivin' down the Freeway"" Driving While Black:"Drivin' down the Freeway" University of Michigan, n.d. Web. 27 Sept. 2012. Wald, Elijah. Escaping the Delta: Robert Johnson and the Invention of the Blues. 1st ed. Vol. 1. New York: Amistad, 2004. Print. Weingroff, Richard. "Adapting Transportation to Jim Crow -The Road to Civil Rights - Highway History - FHWA." Adapting Transportation to Jim Crow -The Road to Civil Rights - Highway History FHWA. U.S. Department of Transportation, 7 Apr. 2011. Web. 26 Sept. 2012.

De Mesa 10

White, Walter. "Investigating Lynchings." Http://nationalhumanitiescenter.org. American Mercury, n.d. Web. Aug.-Sept. 2012. Winborn, Mark. "Deep Blues: Human Soundscapes for the Archetypal Journey." Google Books. Fisher King Press, Sept.-Oct. 2011. Web. 02 Oct. 2012. Young-Eisendrath, Polly, and Terence Dawson. The Cambridge Companion to Jung. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge UP, 2008. Print.

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- Beyond the Crossroads: The Devil and the Blues TraditionDari EverandBeyond the Crossroads: The Devil and the Blues TraditionPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (2)

- Discrimination in The City Race Class AnDokumen8 halamanDiscrimination in The City Race Class AnIsha NisarBelum ada peringkat

- Mask Maker, Mask Maker: The Black Gay Subject in 1970S Popular CultureDokumen30 halamanMask Maker, Mask Maker: The Black Gay Subject in 1970S Popular CultureRajan PandaBelum ada peringkat

- What Is Jazz in Toni Morrison'sDokumen8 halamanWhat Is Jazz in Toni Morrison'sAnonymous SPi3X6MBelum ada peringkat

- Creepy Crawling: Charles Manson and the Many Lives of America's Most Infamous FamilyDari EverandCreepy Crawling: Charles Manson and the Many Lives of America's Most Infamous FamilyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (5)

- A Biographical Literary Analysis of Langston Hughes' "The Blues I'm Playing"Dokumen5 halamanA Biographical Literary Analysis of Langston Hughes' "The Blues I'm Playing"Horus94Belum ada peringkat

- Insane Clown Pantheon: Comparative Mythology and the Dark Carnival. Carnival of Carnage and AzazelDari EverandInsane Clown Pantheon: Comparative Mythology and the Dark Carnival. Carnival of Carnage and AzazelPenilaian: 5 dari 5 bintang5/5 (2)

- A Spectacular Secret: Lynching in American Life and LiteratureDari EverandA Spectacular Secret: Lynching in American Life and LiteratureBelum ada peringkat

- The Man Who Saw a Ghost: The Life and Work of Henry FondaDari EverandThe Man Who Saw a Ghost: The Life and Work of Henry FondaBelum ada peringkat

- Seems Like Murder Here: Southern Violence and the Blues TraditionDari EverandSeems Like Murder Here: Southern Violence and the Blues TraditionPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2)

- Gwendolyn Brooks Study GuideDokumen6 halamanGwendolyn Brooks Study GuideLhamo RichoeBelum ada peringkat

- 22avant-Garde Identity 22 by Blake KeisterDokumen6 halaman22avant-Garde Identity 22 by Blake Keisterapi-678581580Belum ada peringkat

- Fires in The Mirror Is A 1992 Play by Anna Deavere Smith That Dramatizes Interviews ThatDokumen12 halamanFires in The Mirror Is A 1992 Play by Anna Deavere Smith That Dramatizes Interviews Thatapi-302478457Belum ada peringkat

- King Kong Race, Sex, and Rebellion: by David N. RosenDokumen5 halamanKing Kong Race, Sex, and Rebellion: by David N. RosenBode OdetBelum ada peringkat

- Manson Exposed: A Reporter’s 50-Year Journey into Madness and MurderDari EverandManson Exposed: A Reporter’s 50-Year Journey into Madness and MurderPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1)

- Discrimination in "The City": Race, Class, and Gender in Toni Morrison's JazzDokumen9 halamanDiscrimination in "The City": Race, Class, and Gender in Toni Morrison's Jazzsalman777Belum ada peringkat

- 63-Article Text-142-1-10-20180830Dokumen17 halaman63-Article Text-142-1-10-20180830Mihaela GurzunBelum ada peringkat

- Robert Johnson Devils PactDokumen10 halamanRobert Johnson Devils PactRizal Judawinata100% (2)

- Rainbringer: Zora Neale Hurston Against The Lovecraftian MythosDari EverandRainbringer: Zora Neale Hurston Against The Lovecraftian MythosBelum ada peringkat

- Dw2majorassignment4 ResearchDokumen4 halamanDw2majorassignment4 Researchapi-440084977Belum ada peringkat

- The Autobiography of An Ex Coloured ManDokumen4 halamanThe Autobiography of An Ex Coloured ManParthiva SinhaBelum ada peringkat

- Fences - Critical, Dramatic Theory PaperDokumen20 halamanFences - Critical, Dramatic Theory PaperMaimouna CamaraBelum ada peringkat

- Equality: What Do You Think About When You Think of Equality?Dari EverandEquality: What Do You Think About When You Think of Equality?Belum ada peringkat

- Jazz in the Time of the Novel: The Temporal Politics of American Race and CultureDari EverandJazz in the Time of the Novel: The Temporal Politics of American Race and CultureBelum ada peringkat

- Beloved - Slavery HauntingDokumen28 halamanBeloved - Slavery HauntingkevnekattBelum ada peringkat

- The Nazis Next Door: How America Became a Safe Haven for Hitler's MenDari EverandThe Nazis Next Door: How America Became a Safe Haven for Hitler's MenPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (26)

- The Real Ambassadors: Dave and Iola Brubeck and Louis Armstrong Challenge SegregationDari EverandThe Real Ambassadors: Dave and Iola Brubeck and Louis Armstrong Challenge SegregationBelum ada peringkat

- Bumpy JohnsonDokumen4 halamanBumpy JohnsonPerfectKey21100% (1)

- 21 Books To Read in 2018Dokumen15 halaman21 Books To Read in 2018charanmann9165Belum ada peringkat

- Homo Homini LupusDokumen12 halamanHomo Homini LupusHonny Pigai ChannelBelum ada peringkat

- A Politics of Intimacy Jericho Browns THDokumen3 halamanA Politics of Intimacy Jericho Browns THChaimae Zineb BERRIBelum ada peringkat

- Bryan Stevenson: The Lens of Gordon Parks: A Different Picture of Crime in AmericaDokumen3 halamanBryan Stevenson: The Lens of Gordon Parks: A Different Picture of Crime in AmericaivanespauloBelum ada peringkat

- Jazz by Toni Morrison (Title, Themes, Characters)Dokumen4 halamanJazz by Toni Morrison (Title, Themes, Characters)Husnain AhmadBelum ada peringkat

- Damaged Heritage: The Elaine Race Massacre and A Story of ReconciliationDari EverandDamaged Heritage: The Elaine Race Massacre and A Story of ReconciliationBelum ada peringkat

- From Bourgeois to Boojie: Black Middle-Class PerformancesDari EverandFrom Bourgeois to Boojie: Black Middle-Class PerformancesBelum ada peringkat

- Letters to Osama: Old and New Musings on Foreign and Domestic Terrorism...And Other MattersDari EverandLetters to Osama: Old and New Musings on Foreign and Domestic Terrorism...And Other MattersBelum ada peringkat

- RetrieveDokumen14 halamanRetrievealanm0721amBelum ada peringkat

- American Renaissance: A White Teacher Speaks OutDokumen16 halamanAmerican Renaissance: A White Teacher Speaks Out'Hasan ibn-Sabah'Belum ada peringkat

- Crossing Bar Lines: The Politics and Practices of Black Musical SpaceDari EverandCrossing Bar Lines: The Politics and Practices of Black Musical SpaceBelum ada peringkat

- Portrait of a Phantom: The Story of Robert Johnson's Lost PhotographDari EverandPortrait of a Phantom: The Story of Robert Johnson's Lost PhotographBelum ada peringkat

- 3-K.Valarmathi Bluest Eye, FeminismDokumen6 halaman3-K.Valarmathi Bluest Eye, FeminismOntiBelum ada peringkat

- Research EssayDokumen10 halamanResearch Essayapi-437181578Belum ada peringkat

- 1275616KDokumen5 halaman1275616KHerodBelum ada peringkat

- BELOVEDDokumen6 halamanBELOVEDroonil wazlibBelum ada peringkat

- America, Goddam: Violence, Black Women, and the Struggle for JusticeDari EverandAmerica, Goddam: Violence, Black Women, and the Struggle for JusticeBelum ada peringkat

- Rose Colored LensesDokumen2 halamanRose Colored LensesBettinamae Ordiales De MesaBelum ada peringkat

- How To Pray The RosaryDokumen5 halamanHow To Pray The RosaryBettinamae Ordiales De MesaBelum ada peringkat

- 212 - Problem Sets Complete NEWDokumen20 halaman212 - Problem Sets Complete NEWBettinamae Ordiales De MesaBelum ada peringkat

- Bettina de Mesa Ochem 221L Fall 2014 December 5 2014 Bromination and DebrominationDokumen2 halamanBettina de Mesa Ochem 221L Fall 2014 December 5 2014 Bromination and DebrominationBettinamae Ordiales De MesaBelum ada peringkat

- Equilibrium ConstantDokumen4 halamanEquilibrium ConstantBettinamae Ordiales De MesaBelum ada peringkat

- Dante Discussion PaperDokumen2 halamanDante Discussion PaperBettinamae Ordiales De MesaBelum ada peringkat

- Voltaire AnalysisDokumen7 halamanVoltaire AnalysisBettinamae Ordiales De MesaBelum ada peringkat

- Formation of Gay Rights in Los AngelesDokumen15 halamanFormation of Gay Rights in Los AngelesBettinamae Ordiales De MesaBelum ada peringkat

- Calorimetry (Formal)Dokumen17 halamanCalorimetry (Formal)Bettinamae Ordiales De Mesa0% (1)

- Desire by Bob DylanDokumen16 halamanDesire by Bob DylanBettinamae Ordiales De MesaBelum ada peringkat

- Hamlet's SoliloquyDokumen4 halamanHamlet's SoliloquyBettinamae Ordiales De MesaBelum ada peringkat

- To The Virgins, To Make Much of TimeDokumen1 halamanTo The Virgins, To Make Much of TimeBettinamae Ordiales De MesaBelum ada peringkat

- Coronation of The Virgin MaryDokumen5 halamanCoronation of The Virgin MaryBettinamae Ordiales De MesaBelum ada peringkat

- Preachin' The Blues: The Life and Times of Son HouseDokumen217 halamanPreachin' The Blues: The Life and Times of Son HouseElmo R100% (3)

- The Origins of The Mississippi Delta BluesDokumen10 halamanThe Origins of The Mississippi Delta BluesDave van BladelBelum ada peringkat

- Cross Road Blues by Robert JohnsonDokumen10 halamanCross Road Blues by Robert JohnsonBettinamae Ordiales De MesaBelum ada peringkat

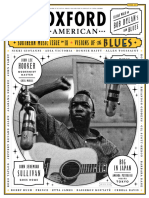

- Oxford American Vol.18 Winter 2016Dokumen164 halamanOxford American Vol.18 Winter 2016Γιάννος ΚυριάκουBelum ada peringkat

- This Content Downloaded From 161.45.205.103 On Sun, 04 Apr 2021 11:29:53 UTCDokumen35 halamanThis Content Downloaded From 161.45.205.103 On Sun, 04 Apr 2021 11:29:53 UTCmidnightBelum ada peringkat

- John Scanlan - Easy Riders, Rolling Stones - On The Road in America, From Delta Blues To 70s Rock (2015, Reaktion Books)Dokumen254 halamanJohn Scanlan - Easy Riders, Rolling Stones - On The Road in America, From Delta Blues To 70s Rock (2015, Reaktion Books)Annie B.Belum ada peringkat

- Christopher Handyside - A History of American Music. Blues (2006)Dokumen53 halamanChristopher Handyside - A History of American Music. Blues (2006)Γιάννος ΚυριάκουBelum ada peringkat

- Richard Daniels - Blues Guitar Inside OutDokumen160 halamanRichard Daniels - Blues Guitar Inside OutBouchaib Lbriki63% (8)