jssisiVolVIIPartLIII 247254

Diunggah oleh

texas_peteJudul Asli

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

jssisiVolVIIPartLIII 247254

Diunggah oleh

texas_peteHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

1878,]'

By Robert Goodbody, Esq.

247

see no signs of it. The great excess of imports, as compared with exports, is confidently appealed to as an undoubted proof that it is; and it would not come within the scope of the paper to examine how the national account is balanced. The state of the exchanges, however, do ; and they show no signs of an unfavourable state of things. Two or three bad harvests, the shutting up of the Black Sea, combined with a good harvest|in |the States, have naturally stimulated the demand for American corn, yet the exchange shows no signs of going to a point which would cause gold to flow to New York. But, it is said, we have been paying in bonds, and so lessening our capital. I do not believe it. The whole import from Europe has not been so very large, and I believe we have imported almost as much of American bonds from the continent as we have sent to New York; and even if some have gone on balances, the indications now are that America will have to begin to export gold; and every day, as the receipts of corn and cotton fall off, these indications may be expected to increase. And in the meantime there is no demand for gold for the continent, except for Germany, against silver. This silver has been going to India, where we have been lending money. But, say the alarmists, the reason that gold does not go to Paris is that there is an increasing quantity of French money attracted here by the higher rates existing as compared with Paris. Up to last June or July money was dearer in Paris than in London, and no doubt English money went to Paris, yet we never heard that that was a proof we were getting richer. On the contrary, we were then told that the case was hopeless, for the French could afford to pay more for money for trade purposes than we could. Now it is hopeless, because we pay more than the French do. I will not weary you further with such absurdities. The wealth of any country depends on its people, where nature has done so much as she has for England. Has any proof been given that English enterprise, English honesty, English capacity has declined1? Until there has, we may leave the national wealth to take care of itself, convinced that if we each do whatever we find to do with all our might, our country will not be behind in the race for success, but will maintain the proud position she has reached by centuries of toil.

IV. On Banks and Banking in Ireland. By James Connolly, Esq.

[ftead 25th June, 1878.]

I AM not aware that any paper has ever been read before the Statistical Society on this very important subject. This is, perhaps, not very surprising. In fact public banks have gradually come into existence one by onecommencing in a very quiet way, with a comparatively small capital, and confining their operations in the first instance to one locality, such as Dublin or Belfast. In this way the Bank of Ireland was established, now nearly a

248

Banks and Banking in Ireland,

{July,

century ago, by an Act of the Irish Parliament, with a capital of 600,000 late currency. It commenced issuing notes to about the same amount. From the very commencement it did a quiet, steady business; but it did not extend its operations beyond Dublin for nearly half a century. In 1824, an Act of Parliament having been passed repealing certain laws which prevented the establishment of joint-stock banks, the Hibernian, Provincial, and Northern Banks came into existence; and then the Eank of Ireland began to open branch banks in the provinces. There are now no less than 409 banking establishments in Ireland. There are besides a large number of sub-offices, where business is carried on weekly, and also, generally speaking, on fair days. In fine, I believe it is no exaggeration to say that there is scarcely a good village in Ireland unprovided with banking accommodation. The only exceptions I know of to this are some of the suburban and watering places in the neighbourhood of Dublin. The explanation to this seems to be, that the professional and business men residing in those places usually come into town every day, where they have their offices and business premises, and that they naturally also bank in the city. ' I conclude from this, that I believe I am justified in saying that no country is so well provided with banking accommodation as thisexcepting, perhaps, England and Scotland ; and notwithstanding occasional complaints which are sometimes heard to the contrary, I verily believe that our banks are at least as liberal as those of any other country. In fine, banks in rural districts give farmers advances, to enable them to seed their lands and reap their crops, which many persons would consider ridiculously small. They even grant loans to labouring men to enable them to plant their potatoes, and to assist them in tiding over the slack season, when labour is scarce. However, it is very satisfactory to find that all the joint-stock banks in the country are reaping the reward of their public spirit and good management; and I find that they are all dividing amongst their shareholders dividends varying from eight (as a minimum) to twenty per cent, on their paid-up capital. The aggregate capital, paid up, of the nine banks, amounts to 6,800,000; the total reserve fund, to 2,700,000. Nor should we overlook the valuable privilege possessed by six of those banksof issuing notes. Assuming their average circulation to be 7,000,000, and deducting two and a-half millions of bullion which the law obliges them to hold, they will still have four and a-half millions for banking purposes free of interest. Besides capital, reserve fund, and the privilege of issuing notes, the banks have also very valuable freehold and leasehold property, consisting of their bank premises, which, if valued one with another at only 2,000 each, would represent over 800,000. In a word, so highly are our banks looked to as safe investments for capital, that the common quotation of the shares is from two and a-half to four-fold the amount of the paid up capital; and the aggregate value of them all round must be nearly, if not quite, three. fold. At all events, I think we may safely put down the total, in

1878.]

By James Connolly, Esq.

249

round numbers, as value for twenty millions sterling. The average total profits of the nine banks must considerably exceed one million sterling, as I find they divide nearly that amount annually in dividends and bonuses, besides which, they carry large sums over to the reserve funds, which I believe have been exclusively formed in that way. I think that I have now pretty well exhausted the banking statistics which are public ; but to my mind the most interesting and most instructive, and, statistically speaking, the most important banking operations lie concealed in the bank ledgers. I here allude to the daily, weekly, monthty, and yearly receipts and payments made through the banks. And here it may be well to prepare the reader for a surprise. We are so accustomed from infancy to have the poverty of the country dinned into our ears, that if we suddenly get a glimpse at the daily financial operations in the interior of our banks, we may imagine we are dreaming, or are taking part in some Arabian tale. Working to a certain extent in the dark, without the required statistics, we must in the first place enquire who are the clients of the banks. It is a matter of notoriety that all merchants and wholesale traders keep current accounts at their bankers, and that as a rule all their cash payments are made by means of cheques; also, that all their legitimate bills are usually made payable at their bankers. Merchants and traders, likewise, generally send into their bankers, bills received by them in the course of trade, for collection. Moreover, they make all remittances to distant places through their bankers. The same is applicable to the pecuniary transactions of all respectable shopkeepers. It is almost needless for me to add that all companies, such as railway, insurance, limited liability companies, etc., all have their bank accounts. The same applies to agents, brokers, salesmasters, millers, solicitors, and professional men of all kinds: likewise to private gentlemen, graziers, and even farmers of the better class now have current accounts in banks. Ladies, tooeven ladies of small meansfind the comfort and security of having their half-year's income securely lodged, instead of running the risk of having their houses broken into and robbed. And here I may state an undoubted and very curious fact which I heard on the best authority. The overwhelming majority of the clients of the Royal Bank, Kingstown, are ladies. This, I think, will surprise both the friends and opponents of the rights of women; and shows that, in matters financial at least, they are silently asserting their emancipation. In a word, " everybody " has now a current account in some bank. Hence I infer that almost always whenever there is a pecuniary payment of any importance, there will be at the very least one bank transaction. I say at least one, because such is the custom now of doing business through agentsI care not whether they are called brokers, factors, salesmasters, auctioneers, land agents, or solicitorsthat one change of stock, property, or rnerchandise commonly involves two, three, or perhaps four different payments through banks. One of the most important statistical facts I found relative to the commercial activity of Ireland, is in Thorn's Directory, under the

250

Banks and Banking in Ireland,

[July,

head of " Belfast." This informs us that in the year 1866 the imports of that city were valued at 12,417,000, and the exports at 11,915,000. Now Belfast is, as everyone knows, the most progressive city in Ireland, and I find that Between the years 1862 and 1872 no less than 17,000 new buildings were erected there. The city valuation was increased from 352,703 in 1866, to 503,686 in 1876. The population, too, increased from 150,000 in 1868, to 210,000 in 1876, or equivalent to forty per cent, in eight years.Vide Belfast Directory, So that it is very evident that the tide of prosperity continues to flow, although the staple manufacture has of late years been very dull. Now, supposing the whole of that trade of 24,000,000 to have been liquidated by means of cheques and bills passing through the * banks, it is very obvious that that immense sum represents but a small portion of the financial operations of those establishments. To explain my meaning, it is only necessary to observe that for every great staple, whether it be a raw material or a manufactured article of commerce, there are always speculators who deal, or as many would say, gamble in them; but, call it what you please, the goods and raw materials pass through their hands, often through many such unproductive hands, and this involves as many payments by cheques or by bills passing through the banks as there are sales. But independent of such jobbing, which appears inevitable in all mercantile transactions, there are the legitimate sub-divisions of trade and manufacture, involving at least one financial action for each change of hand. To illustrate this proposition, almost any article of commerce may be taken at random. As we are now alluding to the trade of Belfast, we cannot do better than see how that staple article of commerce and manufactureflax, passes from hand to hand. The foreign merchant sends it to a consignee, who probably disposes of it to a speculator, who, anticipating a rise in the market, buys up all he has the means of securing. It is by no means improbable that the latter, as soon as he sees his way of securing a fair return for his money, sells it to another jobber who may have idle money on hands, or, what is still more probable, good credit with his bankers. The next change very probably sends the raw material to a spinning factory. It then passes on to a weaving factory. This does not exhaust the processes through which the now partially-manufactured article has to go. It next passes to the bleacher; and I believe there is another branch of linen manufacture, which however, is sometimes united with- the latter, called the finishing. The now completely manufactured linen is, I believe, usually sold to a wholesale merchant, called, if I mistake not, a warehouseman, who passes it to retailers, or perhaps the freight merchant. This tedious detail of the staple manufacture of Belfast. I thought necessary, least it might be thought that my conclusions were far-fetched and exaggerated with respect to the financial operations of the banks in that city. But before going into the latter it is necessary to take a general survey of the commercial activity of that place. I find that ship-building, distilling, brewing, milling (corn), foundry works, and above all the building trade, are in great activity and prosperity. Belfast, top, as the capital of the north, and the terminus of the

1878.]

By James Connolly, Esq.

251

railway in the north, supplies a large district, far and wide, with the necessaries and luxuries of life, which are only to he had in a large city. Finally, Belfast is the financial centre of the province, having six great banks there, three of which were founded in that city and have their boards of directors there. Taking all these matters into consideration, I think it is doing violence to one's better judgment, in order to make my estimate of the financial action of the Belfast banks as moderate and unsensational as possible, if we conclude that it must be at the very least equal to four times Thorn's estimate of the annual imports and exports in 1866, since which the city has increased by 40 per cent. This would give in round numbers one hundred millions a-year as the annual turn-over. This sum, I fully admit, appears prodigious for one city of a small country supposed to be wholly pastoral and agricultural. But if we divide this sum by six, the number of banks in Belfast, and again by 300, which is about the number of banking days in the year, we shall find that it will only be necessary for each to turn over on an average ,55,000 per day to exhaust the whole amount. Now I submit that the sum last mentioned is a very small estimate as the limit to the operations of a great bank in a commercial city of such importance. My own private opinion is that I have very greatly underestimated the financial importance of the capital of the north; for I am sure that any merchant would declare the impossibility of carrying on the trade given by Thorn with the payments implied by my figures. Compared to Belfast, Dublin possesses many advantages. If we add to it the suburbs and watering places at the seaside, where the citizens Teside, and which receive most of their supplies of all kinds from the trading establishments, shops, and markets of the cityin fact, by taking in the metropolitan police district, we shall have a population of over 300,000, or just double that of the former city in 1868. The situation, too, is far more central, and may be described as the terminus of all the Irish railways, and by far the most important port in the country, both for British and foreign trade; it is likewise the chief port for passenger communication. Moreover, it is the seat of the law courts, and the head-quarters of the army and the civil service; and as the residence of the Viceregal court, a large number of the gentry reside here more or less permanently. Distilling, milling, brewing, printing, and foundry works are carried on very extensively; and the annual tonnage of the port, which is rapidly increasing, is considerably more than 1,000,000 tons over that of Belfast,' and about double the tonnage of Belfast in 1866. The building trade is most flourishing both in the city and in the suburbs, and gives most lucrative employment, directly and indirectly, to some thousands of persons. Finally, Dublin is the financial as well as the state capital of Ireland, the seat of many public boards of directors, as well as of the principal, I might perhaps say the only stock exchange in the country, which gives, I believe, a far greater stimulus to banking business than any other trade or profession. Lastly, there are no less than sixteen public and three private banks within the city. With all these facts before us, I cannot, I think, be accused of making any exaggerated calculation, in estimating the annual bank

252

Banks and Banking in Ireland,

[July,

action of Dublin as double that of Belfast. This would give a minimum of 200,009,000; but, according to my private judgment, it would be just as impossible to carry on the financial business of the city within that sum of money(the reader will perceive that this was a slip of my penwe are here speaking of bank operations, ninetenths of which are carried on without any cash payments)vast as it undoubtedly is, as to limit the bank circulation of Belfast, in imagination, to half that amount. Compared to Dublin and Belfast, the trade and commerce of the other cities are small3 but in the aggregate, taking them all together say thirty towns, seventeen of which are seaportsthey undoubtedly carry on a large and flourishing trade. Most of them have mills, breweries, saw mills, foundries, tanneries, and other considerable industries and manufactures, requiring much banking accommodation. I find that the aggregate tonnage of the seventeen ports mentioned, amounts to no less than 5,691,000, which represents nearly a million and a quarter more than that of the port of Dublin. Many of them, especially in Ulster, have spinning and weaving factories, and also bleaching establishments. Those thirty towns must have fully 100 banks, which at the lowest calculation, I conceive, must turn over at least 500,000 each, great and small. Of course for the banks of such towns as Limerick, Cork, Londonderry, etc., this estimate would be ridiculously low. This will amount to fifty millions for the one hundred banks per annum. My private impression is that 50 per cent, might be safely added to that sum. We now come to what I suppose may be called the third class of banks, situated for the most part in small country towns. They are no less than 287 in number. My idea with respect to them is, to give each a circulation of 150,000 per annum, amounting in all to 43,500,000. I trust here again I have kept well within the mark. Thiswould give a total circulation, for the4O9banks,of 393,500,000, or say 400,000,000. I think all this shows that the banks of this country are the mediums through which capital flows through every branch of trade and commerce; and that so far from having produced an artificial scarcity of money, as we frequently hear alleged, the}7 on the contrary do more in the way of facilitating the transactions of business and industry of every description than any other institution whatever. And it is very apparent that, though the banks are compelled, from the downright impossibility of finding suitable investments in this country for their surplus capital, to send a portion of it over to London, the financial capital of the world, to put it out at interest, still it cannot be said that in so doing the country suffers any loss; on the contrary, it is very evident that unless they so acted, they could not afford to pay even the small interest which they at present give on deposits. But even this latter course would be preferable to " locking up," as it is termed, their deposits in investments which cannot be realised within a short period, to meet engagements in case of a sudden crisis or run on the bank. The locking up of capital has been, it is well known, one of the most fruitful causes of banking disasters in England and ^ elsewhere. .But if we take a more enlarged Yiew of tb e matter, we shall

1878.]

'

By James Connolly, Esq.

253

see how utterly impossible it would be to carry on the financial operations I have endeavoured to describe without the agency of banks. Nor should it be forgotten, those financial institutions, being in the enjoyment of the most unbounded credit, are able to carry on by far the greater part of their banking business without having either to receive or pay in gold or bank notes. In fact, the great phenomenon of modern banking is credit, developed to an extent hitherto perfectly unknown. The rational conclusion to draw from this is, that though the banks send out of this country some millions for investment, which they can make no use of at homestill, so far from their causing, by so doing, a scarcity of money in the country, they on the contrary, by their wonderful credit, combined with the whole system of banking, actually create what may be called an artificial plenty of capital. It will be seen that the popular theory, making the farmers the chief clients of the banks, has not been adopted by me. Quite the contrary. My calculations all tended to prove that three-fourths of the banking business of the country is done in some hundred and twenty banks, situated in about thirty of the chief towns, where the farmers' accounts, whether deposit or current, must, I should say, count for very little in comparison with those of the rest of the community at large. I also remarked that, even in rural districts, the largest and best customers of the banks were not of the farming class. The local manufacturers, such as millers, brewers, distillers, maltsters, and builders, together with the resident gentry, agents, solicitors, auctioneers, and shopkeepers, are the persons who keep the accounts most prized by bankers. My object in making those remarks was to correct what I consider a popular fallacyattributing all the wealth and prosperity of the country to that doubtless most important branch of the community, the working farmers. In conclusion, I natter myself that, whatever may be the shortcomings of this essay, all the facts and figures quoted by me, tend, one more strongly than another, to prove to demonstration the one great fact which I have had all through before methe great importance of a statis'tical paper, giving an authentic account of the financial operations of the public banks, and drawn up from official returns from the banks. As there are only nine such companies in Ireland, and as they are all known to be in a highly flourishing state, it appears to me that, so far from having anything to conceal, it would be directly to their advantage to publish to the world the extent and the nature of their transactions which are the causes of their pros-" perity. Hence, I conclude that any member of the Statistical Society undertaking to procure the accounts I have mentioned, would be in a position to contribute a most interesting and important paper to the Society. If he could at the same time procure a classification of the clientsI mean as to their numbers and professions, not forgetting the number and supposed occupations of the lady clientshe would add greatly to the interest of his communication. Another most important item of bank statistics is that of remittances to and out of Ireland, distinguishing, if possible, commercial from private transactions. This, if obtained, would throw a great light on a sub-

254

Banks and Banking in Ireland.

ject much spoken and written about, but of which there is no accu-' rate knowledgeI allude to the absentee drain. In my opinion this is much larger than is usually supposed.

V.Notice of some points in Irish Agricultural Statistics. By James Connolly, Esq.

[Read 25th June, 1878.]

I NOW wish to make a brief communication of a most important and interesting discovery, if I may so call it, which I think I have made with regard to agricultural statistics. In poring over Thorn's article on the latter, I noticed, to my great surprise, that no mention whatever is made of the annual wool clip. Seeing that there are upwards of 4,500,000 sheep in the country, the value must be very considerable. In my opinion, it cannot on an average be less than .1,500,000 at the lowest. I may here observe that, owing to the present universal dulness of trade, there is this year a very heavy fall in the value of this article, as compared to the average of the lastsay eight or tenyears. But a still greater omission is that with regard to dairy farming. This may be said to be one of the great industries of the country. Thorn states that there are upwards of 1,500,000 milch cows in Ireland. If we value them at 13 each on an average, which I consider would be a low estimate, we shall find that the capital invested must be 20,000,000, or thereabouts. Considering the dangerous nature of this stock, which is more liable to disease than any other, and considering also the high rents for grass lands of the best quality, and the expense of artificial feeding in winter, I conclude that a dairy farmer could scarcely save himself, much less make a profit, unless his cows brought him in, one with another, 20 per annum at the very least. This would make the enormous sum of 30,000,000 per annum. The only reference Thorn makes to wool, is by giving the annual export of that article. For dairy farming, he only gives the export of butter, but makes no allusion to the consumption of milk or butter in the country, although both are very largely consumed by the whole population, leaving but a comparatively small portion of the latter for exportation. I am sensible to the fact that thirty millions is an enormous sum, especially if, as I believe, it has hitherto been overlooked, to account for. In fine, I am well aware that the person advancing such a statement will be heard with the greatest distrust. All things considered, I think the simplest way of proving the correctness of my estimate is to take nothing into account but the average price of milk all over the country, and the average quantity produced by cows throughout the year. To this must be added the value of a calf. It is well known that a good cow will give, during

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- Money Answer All ThingsDokumen76 halamanMoney Answer All ThingsJose Artur PaixaoBelum ada peringkat

- Elements of Foreign Exchange: A Foreign Exchange PrimerDari EverandElements of Foreign Exchange: A Foreign Exchange PrimerBelum ada peringkat

- Banks and Their Customers: A practical guide for all who keep banking accounts from the customers' point of viewDari EverandBanks and Their Customers: A practical guide for all who keep banking accounts from the customers' point of viewBelum ada peringkat

- 1947 - The Absurdity of The National Debt - Duke of Bedford PDFDokumen8 halaman1947 - The Absurdity of The National Debt - Duke of Bedford PDFOktubre RojoBelum ada peringkat

- Brunt - Country Banks As Proto-Venture CapitalistsDokumen24 halamanBrunt - Country Banks As Proto-Venture CapitalistsdifferenttraditionsBelum ada peringkat

- The History of BanksDokumen78 halamanThe History of BanksvgowruBelum ada peringkat

- Monetary Reform: Gold and Bills of ExchangeDokumen10 halamanMonetary Reform: Gold and Bills of ExchangeThijs TheunisBelum ada peringkat

- Brief Observations Concerning Trade and Interest of MoneyDokumen11 halamanBrief Observations Concerning Trade and Interest of Moneypedro augustoBelum ada peringkat

- Duke of Bedford - Poverty and Over TaxationDokumen48 halamanDuke of Bedford - Poverty and Over TaxationSxxxxx BxxxxxBelum ada peringkat

- England's Treasure Through Foreign TradeDokumen1 halamanEngland's Treasure Through Foreign TraderadinstiBelum ada peringkat

- History of Banks HildrethDokumen166 halamanHistory of Banks HildrethrahulhaldankarBelum ada peringkat

- The Money MastersDokumen93 halamanThe Money MastersSamiyaIllias100% (1)

- Lecture No.1 (Intro To Money & Banking)Dokumen17 halamanLecture No.1 (Intro To Money & Banking)Usama MubasherBelum ada peringkat

- 021 BisDokumen10 halaman021 BisMax EneaBelum ada peringkat

- Economic Agent OrangeDokumen3 halamanEconomic Agent OrangeTim PriceBelum ada peringkat

- The Swearer’s Bank by Jonathan Swift - Delphi Classics (Illustrated)Dari EverandThe Swearer’s Bank by Jonathan Swift - Delphi Classics (Illustrated)Belum ada peringkat

- Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, Volume 56, Number 350, December 1844Dari EverandBlackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, Volume 56, Number 350, December 1844Belum ada peringkat

- An Example of Communal Currency: The facts about the Guernsey Market HouseDari EverandAn Example of Communal Currency: The facts about the Guernsey Market HouseBelum ada peringkat

- Top GearingDokumen5 halamanTop GearingTim PriceBelum ada peringkat

- An Essay Towards Regulating the Trade, and Employing the Poor of This Kingdom: Whereunto is Added, an Essay Towards Paying Off the Publick DebtsDari EverandAn Essay Towards Regulating the Trade, and Employing the Poor of This Kingdom: Whereunto is Added, an Essay Towards Paying Off the Publick DebtsBelum ada peringkat

- An Essay on the State of England: In Relation to Its Trade, Its Poor, and Its Taxes, for Carrying on the Present War Against FranceDari EverandAn Essay on the State of England: In Relation to Its Trade, Its Poor, and Its Taxes, for Carrying on the Present War Against FranceBelum ada peringkat

- Hume (1752), Political Discourses. of The Balance of TradeDokumen3 halamanHume (1752), Political Discourses. of The Balance of TradebigdigdaddyyBelum ada peringkat

- Seventeen Talks on the Banking Question: Between Uncle Sam and Mr. Farmer, Mr. Banker, Mr. Lawyer, Mr. Laboringman, Mr. Merchant, Mr. ManufacturerDari EverandSeventeen Talks on the Banking Question: Between Uncle Sam and Mr. Farmer, Mr. Banker, Mr. Lawyer, Mr. Laboringman, Mr. Merchant, Mr. ManufacturerBelum ada peringkat

- Chronicle of A Death ForetoldDokumen3 halamanChronicle of A Death ForetoldTim PriceBelum ada peringkat

- The University of Pennsylvania Law ReviewDokumen15 halamanThe University of Pennsylvania Law ReviewAntonio JairBelum ada peringkat

- Full Test Bank For Essentials of Investments 11Th Edition Zvi Bodie Alex Kane Alan Marcus PDF Docx Full Chapter ChapterDokumen34 halamanFull Test Bank For Essentials of Investments 11Th Edition Zvi Bodie Alex Kane Alan Marcus PDF Docx Full Chapter Chapterjuliejordanrjnspqamxz100% (8)

- London Philatelist:: The Forthcoming ExhibitionDokumen28 halamanLondon Philatelist:: The Forthcoming ExhibitionVIORELBelum ada peringkat

- Business Hints For Men and WomenDokumen114 halamanBusiness Hints For Men and WomenBirhanu GebrekidanBelum ada peringkat

- The South Sea BubbleDokumen3 halamanThe South Sea BubbleRAIYYAN COSAINBelum ada peringkat

- A Stiptick for a Bleeding Nation: Or, a safe and speedy way to restore publick credit, and pay the national debtsDari EverandA Stiptick for a Bleeding Nation: Or, a safe and speedy way to restore publick credit, and pay the national debtsBelum ada peringkat

- Summary of Matthew C. Klein & Michael Pettis's Trade Wars Are Class WarsDari EverandSummary of Matthew C. Klein & Michael Pettis's Trade Wars Are Class WarsBelum ada peringkat

- The London Philatelist - Journal of the Philatelic SocietyDokumen40 halamanThe London Philatelist - Journal of the Philatelic SocietyVIORELBelum ada peringkat

- American Banks and American Foreign TradeDokumen8 halamanAmerican Banks and American Foreign TradesreenBelum ada peringkat

- The Story of The Commonwealth BankDokumen16 halamanThe Story of The Commonwealth BankA & L BrackenregBelum ada peringkat

- Financial and Managerial Accounting 6th Edition Wild Test BankDokumen26 halamanFinancial and Managerial Accounting 6th Edition Wild Test BankAngelaMartinezpxjd100% (55)

- London United Kingdom TipsDokumen13 halamanLondon United Kingdom TipsBuen VecinoBelum ada peringkat

- Offshore Banking PDFDokumen54 halamanOffshore Banking PDFSeema Paranjape Bhagwat80% (15)

- (1747) The London Tradesman (Campbell)Dokumen3 halaman(1747) The London Tradesman (Campbell)naokiyokoBelum ada peringkat

- Best Answer - Chosen by VotersDokumen7 halamanBest Answer - Chosen by VotersAshwini MadankarBelum ada peringkat

- Inter TradeDokumen86 halamanInter TradeIriana Salome Hernandez DelgadoBelum ada peringkat

- The Origins of Modern Banking: GoldsmithsDokumen38 halamanThe Origins of Modern Banking: GoldsmithsVaibhav DixitBelum ada peringkat

- Chambers's Edinburgh Journal, No. 445volume 18, New Series, July 10, 1852 by VariousDokumen37 halamanChambers's Edinburgh Journal, No. 445volume 18, New Series, July 10, 1852 by VariousGutenberg.orgBelum ada peringkat

- 1892 Feb 28Dokumen3 halaman1892 Feb 28Eszter FórizsBelum ada peringkat

- Francis - Bacon - of - Usury PDFDokumen3 halamanFrancis - Bacon - of - Usury PDFÁngel MolinaBelum ada peringkat

- Code of Practice For Wind Energy Development in Ireland - Guidelines For Community EngagementDokumen10 halamanCode of Practice For Wind Energy Development in Ireland - Guidelines For Community Engagementtexas_peteBelum ada peringkat

- A House in The Country - 2004 - Rhys-ThomasDokumen3 halamanA House in The Country - 2004 - Rhys-Thomastexas_peteBelum ada peringkat

- RAPEX Alert - SPAX Concrete ScrewsDokumen2 halamanRAPEX Alert - SPAX Concrete Screwstexas_peteBelum ada peringkat

- Foreword: Fire Safety in Pre-SchoolsDokumen47 halamanForeword: Fire Safety in Pre-Schoolstexas_peteBelum ada peringkat

- GM Guide Insulating SheathingDokumen30 halamanGM Guide Insulating Sheathingtexas_peteBelum ada peringkat

- Home Security - DoorsDokumen2 halamanHome Security - Doorstexas_peteBelum ada peringkat

- Irish National Survey of Housing Quality 2001 2002Dokumen14 halamanIrish National Survey of Housing Quality 2001 2002texas_peteBelum ada peringkat

- Assessing Slip Resistance of Resin FloorsDokumen4 halamanAssessing Slip Resistance of Resin Floorstexas_peteBelum ada peringkat

- Climate Action Plan 2019: InfographicDokumen4 halamanClimate Action Plan 2019: Infographictexas_peteBelum ada peringkat

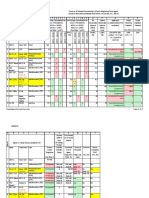

- Annex of Actions 2019Dokumen90 halamanAnnex of Actions 2019texas_peteBelum ada peringkat

- Fire Doors Curtains & Shutters - General Overview & RequirementsDokumen12 halamanFire Doors Curtains & Shutters - General Overview & Requirementstexas_peteBelum ada peringkat

- Interim Climate Actions 2021Dokumen144 halamanInterim Climate Actions 2021texas_peteBelum ada peringkat

- REC Factsheet April 2016Dokumen4 halamanREC Factsheet April 2016texas_peteBelum ada peringkat

- Modern Methods of Construction for BrickworkDokumen16 halamanModern Methods of Construction for Brickworktexas_peteBelum ada peringkat

- Ireland's 2019 Climate Action Plan to Tackle Climate BreakdownDokumen150 halamanIreland's 2019 Climate Action Plan to Tackle Climate Breakdowntexas_peteBelum ada peringkat

- Construction Product Regulation - Questions & Answers For ClientsDokumen3 halamanConstruction Product Regulation - Questions & Answers For Clientstexas_peteBelum ada peringkat

- EirGrid Group Transmission System Geographic Map Sept 2016Dokumen1 halamanEirGrid Group Transmission System Geographic Map Sept 2016texas_peteBelum ada peringkat

- Insulating Historic Solid WallsDokumen17 halamanInsulating Historic Solid Wallstexas_peteBelum ada peringkat

- Blue Guide - 2014 - en PDFDokumen134 halamanBlue Guide - 2014 - en PDFjasonBelum ada peringkat

- Protect your familyDokumen2 halamanProtect your familytexas_peteBelum ada peringkat

- Irc First Aid A2 Poster 09.2013 PDFDokumen1 halamanIrc First Aid A2 Poster 09.2013 PDFtexas_peteBelum ada peringkat

- SK-701 Compliant and Noncompliant Meter Box LocationsDokumen1 halamanSK-701 Compliant and Noncompliant Meter Box Locationstexas_peteBelum ada peringkat

- Safety Advice For Working in The Vicinity of Natural Gas Pipelines A5Dokumen24 halamanSafety Advice For Working in The Vicinity of Natural Gas Pipelines A5texas_peteBelum ada peringkat

- Construction Product Regulation - Questions & Answers For ClientsDokumen3 halamanConstruction Product Regulation - Questions & Answers For Clientstexas_peteBelum ada peringkat

- Ireland's Gas Network: Delivering A Reliable and Secure Gas SupplyDokumen6 halamanIreland's Gas Network: Delivering A Reliable and Secure Gas Supplytexas_peteBelum ada peringkat

- Avoiding Danger From Overhead Electricity LinesDokumen88 halamanAvoiding Danger From Overhead Electricity LinesRonnie Delos SantosBelum ada peringkat

- BS7543Dokumen7 halamanBS7543texas_peteBelum ada peringkat

- Tool Box Talks ConstructionDokumen12 halamanTool Box Talks Constructiontexas_peteBelum ada peringkat

- ESB Construction SafetyDokumen12 halamanESB Construction Safetytexas_peteBelum ada peringkat

- Guide To Insulating Sheathing: Revised January 2007Dokumen30 halamanGuide To Insulating Sheathing: Revised January 2007texas_peteBelum ada peringkat

- Digital Communication Quantization OverviewDokumen5 halamanDigital Communication Quantization OverviewNiharika KorukondaBelum ada peringkat

- FALL PROTECTION ON SCISSOR LIFTS PDF 2 PDFDokumen3 halamanFALL PROTECTION ON SCISSOR LIFTS PDF 2 PDFJISHNU TKBelum ada peringkat

- Sekolah Menengah Kebangsaan Ss17 JALAN SS17/1, Subang Jaya English Scheme of Work Form 3Dokumen11 halamanSekolah Menengah Kebangsaan Ss17 JALAN SS17/1, Subang Jaya English Scheme of Work Form 3Rohana YahyaBelum ada peringkat

- Boiler Check ListDokumen4 halamanBoiler Check ListFrancis VinoBelum ada peringkat

- Learning Stations Lesson PlanDokumen3 halamanLearning Stations Lesson Planapi-310100553Belum ada peringkat

- Lanegan (Greg Prato)Dokumen254 halamanLanegan (Greg Prato)Maria LuisaBelum ada peringkat

- Clean Agent ComparisonDokumen9 halamanClean Agent ComparisonJohn ABelum ada peringkat

- Exor EPF-1032 DatasheetDokumen2 halamanExor EPF-1032 DatasheetElectromateBelum ada peringkat

- Binomial ExpansionDokumen13 halamanBinomial Expansion3616609404eBelum ada peringkat

- Colour Ring Labels for Wireless BTS IdentificationDokumen3 halamanColour Ring Labels for Wireless BTS Identificationehab-engBelum ada peringkat

- 5 Important Methods Used For Studying Comparative EducationDokumen35 halaman5 Important Methods Used For Studying Comparative EducationPatrick Joseph63% (8)

- NameDokumen5 halamanNameMaine DagoyBelum ada peringkat

- The Product Development and Commercialization ProcDokumen2 halamanThe Product Development and Commercialization ProcAlexandra LicaBelum ada peringkat

- Ramdump Memshare GPS 2019-04-01 09-39-17 PropsDokumen11 halamanRamdump Memshare GPS 2019-04-01 09-39-17 PropsArdillaBelum ada peringkat

- Fong vs. DueñasDokumen2 halamanFong vs. DueñasWinter Woods100% (3)

- Test Bank For Core Concepts of Accounting Information Systems 14th by SimkinDokumen36 halamanTest Bank For Core Concepts of Accounting Information Systems 14th by Simkinpufffalcated25x9ld100% (46)

- Unit 1 Writing. Exercise 1Dokumen316 halamanUnit 1 Writing. Exercise 1Hoài Thương NguyễnBelum ada peringkat

- PREMIUM BINS, CARDS & STUFFDokumen4 halamanPREMIUM BINS, CARDS & STUFFSubodh Ghule100% (1)

- Afu 08504 - International Capital Bdgeting - Tutorial QuestionsDokumen4 halamanAfu 08504 - International Capital Bdgeting - Tutorial QuestionsHashim SaidBelum ada peringkat

- Clogging in Permeable (A Review)Dokumen13 halamanClogging in Permeable (A Review)Chong Ting ShengBelum ada peringkat

- Um 0ah0a 006 EngDokumen1 halamanUm 0ah0a 006 EngGaudencio LingamenBelum ada peringkat

- 2016 Mustang WiringDokumen9 halaman2016 Mustang WiringRuben TeixeiraBelum ada peringkat

- General Separator 1636422026Dokumen55 halamanGeneral Separator 1636422026mohamed abdelazizBelum ada peringkat

- Biomotor Development For Speed-Power Athletes: Mike Young, PHD Whitecaps FC - Vancouver, BC Athletic Lab - Cary, NCDokumen125 halamanBiomotor Development For Speed-Power Athletes: Mike Young, PHD Whitecaps FC - Vancouver, BC Athletic Lab - Cary, NCAlpesh Jadhav100% (1)

- sl2018 667 PDFDokumen8 halamansl2018 667 PDFGaurav MaithilBelum ada peringkat

- SEO Design ExamplesDokumen10 halamanSEO Design ExamplesAnonymous YDwBCtsBelum ada peringkat

- Material Safety Data Sheet Lime Kiln Dust: Rev. Date:5/1/2008Dokumen6 halamanMaterial Safety Data Sheet Lime Kiln Dust: Rev. Date:5/1/2008suckrindjink100% (1)

- Miami Police File The O'Nell Case - Clemen Gina D. BDokumen30 halamanMiami Police File The O'Nell Case - Clemen Gina D. Barda15biceBelum ada peringkat

- IntroductionDokumen34 halamanIntroductionmarranBelum ada peringkat

- Sieve Shaker: Instruction ManualDokumen4 halamanSieve Shaker: Instruction ManualinstrutechBelum ada peringkat