Felner - A Toolkit To Monitor The Realization of ESC Rights PDF

Diunggah oleh

Cibelle ColmanettiDeskripsi Asli:

Judul Asli

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Felner - A Toolkit To Monitor The Realization of ESC Rights PDF

Diunggah oleh

Cibelle ColmanettiHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Closing the Escape Hatch: A Toolkit to Monitor the Progressive Realization of Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights

EITAN FELNER Abstract

Downloaded from http://jhrp.oxfordjournals.org/ at Fundao Getlio Vargas/ RJ on August 13, 2012

A basic paradox underlies much work on economic, social, and cultural rights. At the level of theory, there is widespread recognition among experts and advocates that the obligation to progressively realize these rights to the maximum of a states available resources is at the heart of their realization. However, at the practical level in terms of monitoring efforts, eld investigations, and adjudication by courts this key obligation has largely been sidelined, and the focus instead has been on various immediate obligations related to these rights, which are not dependent on resource availability. This article argues that while this focus has been effective in many ways, circumventing the standard of progressive realization has severely constrained the ability of the human rights movement to hold governments accountable for policies and practices that turn millions of people into victims of avoidable deprivations such as illiteracy, malnutrition, preventable diseases, and homelessness. The article then proposes a methodological toolkit to monitor the obligation of progressive realization. This toolkit has two components: (1) a basic framework of three steps, each with its own simple methods; (2) a set of more sophisticated tools that have been developed in recent years by various researchers or used by civil society organizations. These methods can be powerful tools of social change, allowing us to expand the areas of government policy that come under scrutiny and accountability and to provide objective validity to claims that often the issue is not resource availability but rather resource distribution. Admittedly, addressing issues subject to progressive realization is not easy. It requires grappling with difcult normative and policy problems related to resource constraints and trade-offs, as well as delving into data. These are not typically areas of human rights expertise. Nevertheless, the human rights movement is now mature enough to overcome these challenges.

Keywords: accountability; available resources; economic and social rights; monitoring; progressive realization; quantitative methods Introduction A basic paradox underlies much work on economic, social, and cultural (ESC) rights. At the level of theory, there is widespread recognition among experts and advocates that the obligation to progressively realize these rights to the maximum of a states available resources is at the heart of their realization.1

1 As Philip Alston and Gerard Quinn point out, the concept of progressive achievement is the lynchpin of the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights

Journal of Human Rights Practice Vol 1 | Number 3 | 2009 | pp. 402 435 DOI:10.1093/jhuman/hup023 # The Author (2009). Published by Oxford University Press. All rights reserved.

403 Monitoring Progressive Realization of ESC rights

However, at the practical level in terms of monitoring efforts by UN Treaty Bodies of specic State Parties, eld investigations by NGOs, and adjudication by courts of concrete cases this key obligation has been largely put aside. Instead, the primary focus has been on various immediate obligations related to this set of rights, which are not dependent on resource availability.2 These obligations include the duty to respect, which requires states to refrain from interfering with peoples exercise of a right; the duty to protect, which requires states to prevent human rights violations by third parties,3 as well as the most tangible aspects of the duty to guarantee the exercise of rights without discrimination, particularly discriminatory laws or practices carried out by public ofcials, such as doctors, teachers, etc. This focus on immediate obligations has been effective in many ways, strengthening the legitimacy of the concept of ESC rights, as well as facilitating work in this area by human rights monitoring bodies, NGOs, national human rights institutions, and courts. However, sidestepping the standards of resource availability and progressive realization has severely constrained the ability of the human rights movement to address broader issues of public policy that have a huge impact on the realization of ESC rights. Millions of people around the world are victims of avoidable deprivations such as illiteracy, preventable diseases, malnutrition, and homelessness that cannot be attributed to violations of the duties to respect or protect human rights. Whether these people can effectively enjoy their ESC rights depends to a large extent on whether they have access to essential services such as adequate health care or quality education, and such access largely (albeit not only) depends on the availability of resources. For instance, to ensure the effective enjoyment of the right to education, there is often a need for enhancing school services, such as improving school infrastructure, providing better training to teachers, and paying them an adequate salary to encourage qualied people to become teachers and to remain in the educational system. There is also a need for demand-side programmes aimed at encouraging children, particularly those from poor families, to come to, and remain in, school. Such programmes could include providing school meals and granting scholarships in the form of cash transfers or in-kind (e.g. free

(ICESCR): Upon its meaning turns the nature of state obligations. Most of the rights granted depend in varying degrees on the availability of resources and this fact is recognized and reected in the concept of progressive achievement(Alston and Quinn, 1987: 172). On the centrality of this obligation for economic and social rights, see also Craven (1995: 129 130) and Roberston (1994: 694). This approach was coined several years ago by Audrey Chapman as a violations approach for monitoring ESC rights (see Chapman, 1996). In addition to these two types of obligations, states are also bound to fulll economic and social rights. This third type of state obligation, which includes promoting rights, facilitating access to rights, and providing for those unable to provide for themselves, requires active intervention on the part of the State and is subject to progressive realization according to the maximum of available resources.

Downloaded from http://jhrp.oxfordjournals.org/ at Fundao Getlio Vargas/ RJ on August 13, 2012

2 3

Eitan Felner 404

uniforms and textbooks) to offset both the direct costs of education and its opportunity costs.4 Therefore, elucidating the precise meaning of the notions of progressive achievement and maximum available resources, and having effective tools to monitor compliance of any state with these obligations in concrete situations, is essential to give real meaning to these rights for many people who are deprived of the most basic needs. Moreover, without such tools, advocacy efforts could be severely undermined. Governments may use the notion of progressive realization as an escape hatch, to avoid complying at all with their human rights obligations (Leckie, 1998: 94), claiming, for instance, that the lack of progress is due to insufcient resources when, in fact, the problem is often not the availability but rather the distribution of resources. The need for these tools is more acute nowadays with the global economic crisis, which is reducing the ability of many poor countries to mobilize adequate resources for the realization of ESC rights; and this at a time when the most vulnerable people in all countries will inevitably be most affected by the crisis and therefore would need increased protection from the state (for instance, in the form of social safety nets). Under these circumstances, it is to be expected that many governments may invoke the concept of progressive realization to explain why they have not made sufcient progress (or have altogether regressed) in such goals as reducing child mortality, increasing the proportion of children nishing primary school, or closing the gap in malnutrition between various segments of their population. Without appropriate tools to assess the standard of progressive realization, it would be virtually impossible to determine the validity of such arguments. This article proposes a methodological toolkit to monitor the obligation of progressively achieving the full realization of ESC rights to the maximum of a states available resources, with regard to specic rights in concrete situations. It argues that quantitative tools are crucial for monitoring the impact of public policies related to resource allocation and distribution on the enjoyment and realization of ESC rights. While the methods proposed here focus primarily on the rights to health and education, they could be readily adaptable to monitor other rights as well. The toolkit proposed here for monitoring the standard of progressive realization is part of a larger project that I am working on, the aim of which is to develop a set of qualitative and quantitative tools that would enable the human rights movement to address broader issues of public policy that have a huge impact on the realization of ESC rights and expand the areas of government policy that we can submit to human rights scrutiny and accountability (Felner, 2008).

4 The opportunity costs in this context refer to the cash earnings or other contributions that a household sacrices in order to keep a child in school rather than in work.

Downloaded from http://jhrp.oxfordjournals.org/ at Fundao Getlio Vargas/ RJ on August 13, 2012

405 Monitoring Progressive Realization of ESC rights

The article begins with a short discussion about the meaning of the notions of progressive realization and maximum available resources and then analyzes reasons why, for all practical purposes, the human rights movement has so far largely ignored these key principles in the eld of ESC rights. Then, it examines a number of approaches that human rights experts and monitoring bodies have suggested and sporadically used to monitor compliance with this obligation. The main part of the article sets out the methodological toolkit proposed to monitor the obligation of progressive realization. This toolkit has two components. First, a basic framework of three steps, each with its own simple methods, which could potentially be used by virtually anybody interested in monitoring ESC rights. Then, a short description of some more sophisticated tools that have been developed in recent years by various researchers or used by civil society organizations. Finally, the conclusions suggest why the time is ripe to adopt tools that will enable us to systematically assess the standard of progressive realization and how these methods could be powerful tools of social change. Why Has the Human Rights Movement Sidelined the Notion of Progressive Realization? Article 2(1) of the ICESCR (hereafter the Covenant) states: Each State Party to the present Covenant undertakes to take steps, individually and through international assistance and co-operation, especially economic and technical, to the maximum of its available resources, with a view to achieving progressively the full realization of the rights recognized in the present Covenant by all appropriate means, including particularly the adoption of legislative measures.5 The UN Committee on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights (the body responsible for monitoring compliance with the Covenant hereafter the Committee) has stressed the importance of this clause for the overall understanding of the legal obligations imposed by the Covenant, noting that Article 2(1) is of particular importance to a full understanding of the Covenant and must be seen as having a dynamic relationship with all of the other provisions. It describes the nature of the general legal obligations undertaken by States Parties to the Covenant.6

5 Similar provisions about progressive realization are set out in Article 4 of the Convention on the Rights of the Child; Article 4(2) of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities; and Article 26 of the American Convention on Human Rights. CESCR. General Comment 3: The Nature of States Parties Obligations. 1990. Available at http://www.unhchr.ch/tbs/doc.nsf/(Symbol)/94bdbaf59b43a424c12563ed0052b664? Opendocument (retrieved 1 August 2009).

Downloaded from http://jhrp.oxfordjournals.org/ at Fundao Getlio Vargas/ RJ on August 13, 2012

Eitan Felner 406

The obligation of progressive realization reects the recognition that adequate resources are a crucial condition for the realization of ESC rights.7 In fact, the notion of progressive realization reects the contingent nature of a states obligations regarding this set of rights, insofar as the level of a countrys economic development determines the level of its obligations with regard to any of the rights of the Covenant (Alston and Quinn, 1987: 177). These concepts introduce a exible element to the obligations pertaining to ESC rights. As Paul Hunt points out:

Downloaded from http://jhrp.oxfordjournals.org/ at Fundao Getlio Vargas/ RJ on August 13, 2012

Both phrases progressive realization and resource availability have two crucial implications. Firstly, they imply that some (but not necessarily all) States Parties obligations under the Covenant may vary from one State to another. Second, they imply that, in relation to the same State Party, some (but not necessarily all) obligations under the Covenant may vary over time. (Hunt, 1998: para. 4) In other words, although all State Parties to the Covenant assume the same treaty obligation, a rich State Party would be expected to be able to secure a higher level of rights realization than a poorer State Party. It is in light of these inherently exible elements that we should understand the ongoing reluctance of human rights advocates to use these standards in their practical work, preferring as they usually do to focus primarily on immediate obligations. This reluctance is related to a number of factors. First, the focus on immediate obligations has to be seen in the context of the ongoing efforts of the human rights movement to reinforce the legitimacy of ESC rights as real rights, against repeated critiques (Dowell-Jones, 2004). Such critiques are largely based on the inevitable uncertainty introduced by the exible elements of the obligation of progressive realization with regard to the nature and extent of the legal obligations imposed by the Covenant. Opponents of the idea of ESC rights often claim that the fact that these rights are subject to progressive realization turn them into merely aspirational goals, too vaguely dened to impose clear obligations on states. Much of their criticism hinges on what they see as inherent distinctions between the two sets of rights. In the view of the critics, civil and political rights have the characteristics of real rights they are negative in nature, requiring only state abstention; they are cost-free; and they could be immediately implemented whereas, in contrast, ESC rights lack all of these

7 This is supported by empirical evidence that has generally shown strong linkages between the wealth of countries and the level of enjoyment of ESC rights by their citizens. For instance, a review of the literature on health concludes that There is no doubt that economic growth has been a major factor underlying the long-term improvements in health outcomes. And there can be little doubt that slow economic growth has meant slow progress on health outcomes. It has been estimated, for example, that half a million child deaths would have been averted in Africa in 1990 alone if the continents economic growth in the 1980s had been 1.5 percentage points higher (Wagstaff and Claeson, 2004: 71 72).

407 Monitoring Progressive Realization of ESC rights

characteristics they are positive in nature; require state involvement; depend upon resources; and can only be secured over time. In countering these arguments, human rights experts have rightly insisted that at the level of theory, both sets of rights have more similarities than are often recognized. They both impose negative and positive duties which sometimes require signicant resources and sometimes do not, and which can sometimes be implemented immediately and sometimes not. At the same time, in their eagerness to strengthen the legitimacy of ESC rights, human rights advocates have focused, on a practical level, on those aspects of ESC rights that are typically associated with civil and political rights namely on those aspects that impose negative obligations of state abstention, that can be immediately implemented, and where duties are not subject to resource availability and therefore do not vary according to levels of economic development. This strategy has been particularly useful in strengthening the justiciability of ESC rights. Several courts around the world have issued decisions about violations of immediately effective duties, such as discriminatory legislation or practices, forced labour, or violations of the right to fair remuneration. Conversely, it is more difcult to bring to court cases regarding progressive realization, which are typically related to resource prioritization, since judges are often reluctant to adjudicate on such issues which they often considered as a prerogative of the political branches of a state. Such cases are also difcult to bring to court because they often require relying on empirical data to prove causal links between inadequate progress on the enjoyment of a specic right and state action or inaction, and such causal links may not always be admissible in courts (ICJ, 2008: 29). A focus on immediate obligations, such as issues related to direct interference by a state with the enjoyment of ESC rights (the duty to respect) or manifest discriminatory practices, is also the preferred approach of many NGOs whose primary working methodology is related to naming and shaming specic states and their governments for human rights violations (Roth, 2004). Although states can also commit human rights violations with regard to progressive realization,8 it is easier to establish a violation when dealing with breaches of immediate duties, which typically involve eventbased violations, than to prove violations of duties subject to progressive realization, which are usually related to structural issues and public policies.9 Another reason why human rights advocates have been reluctant to focus on issues subject to progressive realization is, as noted above, their fear that this notion could be misused by many governments as an excuse to avoid all

8 9 Maastricht Guidelines. 1997. Maastricht Guidelines on Violations of Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. Maastricht, 2226 January 1997 Guidelines 14(f) and 15(e). In fact the violations approach was originally proposed as an alternative paradigm to the standard of progressive realization for assessing state compliance with ESC rights (Chapman, 1996: 23 24).

Downloaded from http://jhrp.oxfordjournals.org/ at Fundao Getlio Vargas/ RJ on August 13, 2012

Eitan Felner 408

obligations imposed by the Covenant, since such governments can always postpone implementing their obligations, arguing that the rights enumerated by the Covenant are subject to progressive realization and therefore do not require immediate implementation. Additionally, they could argue that whatever progress they are making towards the realization of these rights is sufcient to comply with their obligations, since these are subject to the maximum of available resources. The variable nature of the obligations subject to progressive realization also complicates any monitoring effort. Neither the Covenant, nor the Committee, provide specic guidance or benchmarks for judging whether a state is making sufcient progress given its levels of available resources or for assessing the sufciency of resources made available to realize rights. This makes it difcult to assess if governments have met this obligation, particularly since such assessment requires a methodology that integrates statistical indicators and quantitative tools that could track progress over time and assess resource availability. Typically, these tools are not part of human rights organizations research toolkit, which in many cases were originally developed to monitor civil and political rights.10 Current Approaches to Monitoring Progressive Realization Given all these challenges, it is not surprising that as several commentators have pointed out, little progress has been made in elucidating the precise meaning of these duties, or in developing appropriate monitoring tools to assess compliance with these obligations in concrete situations. Already 15 years ago, Robert Roberston, in one of the only articles focusing on the obligation to devote the maximum of available resources to realize ESC rights, noted that debate on this question remains at a high level of generality, adding that little progress has been made in creating a set of workable standards which are detailed, systematic, and authoritative and, as of yet, there is no answer to the question: What resources must be devoted to realizing ICESCR rights? (Roberston, 1994: 703). More recently, one of the most comprehensive studies on the nature of the obligations under the Covenant made a similar argument: The indicators developed by the Committee to measure compliance with the obligation to devote the maximum of available resources need to be further improved. So far, these indicators have enabled the Committee only to make general statements and they tend to use rather weak language. Moreover, the Committee has not applied them in a

10 A few notable exceptions include the work of several NGOs that have been engaged in assessing economic and social rights using budget analysis, such as Fundar in Mexico, the Childrens Budget Project at the Institute for Democracy in South Africa, and DISHA in India, as well as the use of epidemiology in research conducted by Physicians for Human Rights.

Downloaded from http://jhrp.oxfordjournals.org/ at Fundao Getlio Vargas/ RJ on August 13, 2012

409 Monitoring Progressive Realization of ESC rights

consistent and strict manner to all States in the same circumstances. (Sepulveda, 2003: 319) Nevertheless, some attempts have been made to overcome the difculties in accurately monitoring state compliance with the obligation of progressive realization according to maximum available resources. For this purpose, human rights experts and monitoring bodies have suggested and sporadically used a number of approaches to monitor compliance with this obligation. What follows is a short description and analysis of the main suggestions. Use of Indicators One frequent recommendation has been to employ statistical indicators.11 For instance, the UN Special Rapporteur on the Realization of Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights observed in 1990 that [. . .] indicators probably provide the most effective means of measuring the progressive achievement of the rights found in the Covenant.12 In 1993, the World Conference on Human Rights recommended that a system of indicators be developed to measure progress in the realization of ESC rights as did the Committee on several occasions.13 In recent years, the Ofce of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) has spearheaded the systematization of the work on human rights indicators, in response to a request by the Chairpersons of the UN Treaty Bodies. With the help of a panel of experts, OHCHR has developed a conceptual and methodological framework for using quantitative indicators to monitor the implementation of ESC, as well as civil and political, rights. On the basis of this proposed framework, OHCHR put forward a sample list of indicators for selected human rights, thereby contributing to the translation of the normative content of substantive rights into quantitative indicators (see OHCHR, 2008) Nevertheless, it remains to be seen how this framework will address the most difcult challenge for measuring the obligation of progressive realization, namely, to suggest specic methods through which the UN Treaty

11 12 13 An indicator can be dened as a fact that indicates the state or level of something (e.g. literacy rates). UN Special Rapporteur on the Realization of ESCR (Danilo Tu rk). 1990. Realization of Economic, Social and Cultural Rights Progress Report. E/CN.4/Sub.2/1990/19. Vienna Declaration and Programme of Action. World Conference on Human Rights, Vienna, 1415 June 1993, A/CONF.157/23. See, for example, CESCR. General Comment 12, The Right to Food. 1999, para. 43. Available at http://www.unhchr.ch/ tbs/doc.nsf/(Symbol)/3d02758c707031d58025677f003b73b9?Opendocument (retrieved 1 August 2009); and CESCR. General Comment 13, The Right to Education. 1999, para 52. Available at http://www.unhchr.ch/tbs/doc.nsf/(Symbol)/ ae1a0b126d068e868025683c003c8b3b?Opendocument (retrieved 1 August 2009).

Downloaded from http://jhrp.oxfordjournals.org/ at Fundao Getlio Vargas/ RJ on August 13, 2012

Eitan Felner 410

Bodies (or other actors engaged in human rights monitoring, such as national human rights institutions or national and international NGOs) can determine whether the progress made by a State Party over a period of time on any given socio-economic indicator has been sufcient to be in compliance with the obligation of progressive achievement according to the maximum of available resources. Use of Benchmarks

Downloaded from http://jhrp.oxfordjournals.org/ at Fundao Getlio Vargas/ RJ on August 13, 2012

One complementary method that has been repeatedly suggested to deal with this challenge is combining the use of indicators with the use of benchmarks.14 According to this approach, monitoring bodies, such as the Committee, request states to set their own benchmarks for key indicators (e.g. child mortality or adult literacy) to be achieved over a period of time. Progress against these benchmarks can then be monitored and assessed by those monitoring bodies. To ensure that states set realistic, but sufciently ambitious, benchmarks for the progressive realization of rights, a process of scoping has been suggested, whereby the Committee would discuss with the State Party the benchmarks against which progress is to be evaluated over a reporting period.15 Despite its merits, the benchmark approach has proved difcult to implement until now. Thus, although this approach has been proposed frequently by the Committee, beginning with its rst General Comment in 1989,16 to date it has not actually been used to monitor compliance of any specic State Party. This may be partly attributed to the fact that, as Danilo Tu rk suggested when he served as the UN Special Rapporteur on the Realization of Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights, most states are wary of making explicit public commitments towards the realization of ESC rights. 17

14 In the human rights literature, benchmarks are targets relating to a given human rights indicator (e.g. child mortality rates) to be achieved over a period of time (e.g. halve the child mortality rates in 10 years). CESCR. General Comment 14: The Right to the Highest Attainable Standard of Health. 2000, para. 58. Available at http://www.unhchr.ch/tbs/doc.nsf/(Symbol)/ 40d009901358b0e2c1256915005090be?Opendocument (retrieved 1 August 2009); CESCR. General Comment 15: The Right to Water. 2003, para 54. Available at http:// www.unhchr.ch/tbs/doc.nsf/0/a5458d1d1bbd713fc1256cc400389e94/$FILE/ G0340229.pdf (retrieved 27 August 2009). The benchmark approach is currently being further developed by Eibe Riedel, a member of the Committee, in co-operation with FIAN International the project is called IBSA (Indicators, Benchmarking, Scoping, and Assessment). See http://ibsa.uni-mannheim.de/. CESCR. General Comment 1: Reporting by State Parties. 1989, para. 6. Available at http:// www.unhchr.ch/tbs/doc.nsf/(symbol)/CESCR+General+comment+1.En?OpenDocument (retrieved 27 August 2009). UN Special Rapporteur on the Realization of ESCR (Danilo Tu rk). 1992. Realization of Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, Final Report. E/CN.4/Sub.2/1992/16 para. 129.

15

16

17

411 Monitoring Progressive Realization of ESC rights

However, the limited use made so far of the benchmark approach as a means to assess progress may also be related to inherent problems in its implementation. Thus, even states that are in principle willing to make explicit public commitments towards the realization of ESC rights may be in no better position than the Committee to set benchmarks that realistically reect the use of maximum available resources for the progressive realization of these rights. More importantly, it is not clear how the use of nationally set benchmarks would solve the problem we noticed regarding the indicators approach, namely the lack of clear criteria and guidance by which to judge whether benchmarks set by governments are sufciently challenging. As Siddiqur Osmani points out: [. . .] when indicators and benchmarks are used to assess the progressive realization of rights, the question inevitably arises of how to determine what would be a realistic and reasonable pace of progress in the light of the available resources [. . .] the problem is how can we know that the plan adopted and implemented by a State does actually represent the best possible use of available resources? What if the State deliberately adopts too unambitious a plan, spending relatively few resources for the enhancement of peoples rights to food, health and education, and yet claims that it is moving towards progressive realization of rights to the best of its ability given the resource constraint? Similarly, when a plan fails to be implemented in full and the State claims that the shortfall was caused by factors beyond its control, how can we be sure that there was indeed nothing more the State could possibly do? To put it bluntly, how can we make sure that the State does not cheat? (Osmani, 2000: 291) Osmani adds that one might think that an expert body, like the Committee on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights, could ensure this by carrying out an independent economic analysis of the resource constraints facing a State Party, but as Audrey Chapman points out, the Committee has neither the time nor the expertise to engage in such an exercise (Chapman, 2007: 161).18 Expenditure Allocation to Specic Sectors Another approach often adopted by the Treaty Bodies to assess state compliance with the obligation to devote the maximum available resources consists of the analysis of macro-level budget information, particularly the percentage

18 Osmani rejects the idea of relying on the Committee for carrying out an analysis of resource constraints facing a State party based on other grounds: resource constraint entails trade-offs, and trade-offs involve value judgments, and value judgments are not in the domain of independent experts (Osmani, 2000: 291).

Downloaded from http://jhrp.oxfordjournals.org/ at Fundao Getlio Vargas/ RJ on August 13, 2012

Eitan Felner 412

of the national budget allocated to a specic social sector (e.g. health, education, etc.). For such purposes, the guidelines for periodic reports adopted by the Treaty Bodies request states to provide information on resources allocated to such sectors. The importance afforded to this type of indicator for the purpose of measuring the obligation to devote the maximum of available resources is reected by the following statement by the Committee on the Rights of the Child: No State can tell whether it is fullling childrens economic, social and cultural rights to the maximum extent of . . . available resources [ . . . ], unless it can identify the proportion of national and other budgets allocated to the social sector and, within that, to children, both directly and indirectly.19 Based on this type of information, the monitoring bodies have made critical observations on various occasions about the compliance of State Parties to their human rights obligations. For instance, in the Concluding Observations of the Second Periodic Report of the Republic of Korea, the Committee noted with concern the high level of defence [sic] expenditure is in contrast with the shrinking budget for key areas of economic, social and cultural rights.20 Similarly, in its Concluding Observations on the state of implementation of the Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights in Kenya made after many years in which this State Party failed to submit a report to the Committee the Committee expressed concern about the fact that government expenditure on health care appears to be constantly decreasing.21 Obviously, increased budget allocation to social sectors does not guarantee adequate provision of quality services. However, all too often, the effective use of additional resources in these sectors can indeed be crucial to increase the availability, affordability, or quality of these services. Nevertheless, although the percentage of budgetary allocations of a state to a specic social sector could indeed, in many circumstances, be an indication of the level of government commitment to promoting that sector, it should not be used as a single indicator for assessing compliance (or lack thereof) of its obligation to the progressive realization of the relevant right. This is because there are multiple factors related to the availability of resources in any state

19 Committee on the Rights of the Child, General Comment 5. General Measures of Implementation of the Convention on the Rights of the Child. 2003, para 51. Available at http://www.unhchr.ch/tbs/doc.nsf/898586b1dc7b4043c1256a450044f331/ 3bba808e47bf25a8c1256db400308b9e/$FILE/G0345514.pdf (retrieved 27 August 2009). CESCR. Concluding Observations on the Second Periodic Report of Korea. 2001 (E/ C.12/1/Add.59) para. 9. Available at http://www.unhchr.ch/tbs/doc.nsf/(Symbol)/E.C. 12.1.Add.59.En?Opendocument (retrieved 27 August 2009). CESCR. Concluding Observation on the State of Implementation by Kenya. (E/1994/23) para. 83. Available at http://www.bayefsky.com/html/kenya_t4_cescr.php (retrieved 27 August 2009).

Downloaded from http://jhrp.oxfordjournals.org/ at Fundao Getlio Vargas/ RJ on August 13, 2012

20

21

413 Monitoring Progressive Realization of ESC rights

that bear upon the progressive realization of ESC rights other than the budget proportion that a state allocates to a specic social sector. These factors include: (a) Impact of economic growth on the expenditure spent per person on a given social sector If the overall size of its economy increases, a state can devote more resources to social sectors like education, health, or food security without necessarily allocating a bigger proportion of its economic resources to these sectors. As a study on the relationship between the levels of economic development, health outcomes, and health expenditure noted: The most important source of increased health expenditure is economic growth. Even if the share of health spending in GDP remains constant, economic growth translates into more spending on health (Preker, 2003: ii). Therefore, a monitoring exercise that only looks at the proportion of expenditure allocated to social sectors, without also looking at the levels of economic growth or expenditure per capita, may reach the conclusion that such a state is not complying with its obligation to devote the maximum of available resources. However, the additional resources allocated to a given sector as a result of economic growth may be sufcient to adequately full its obligations of progressive realization, and therefore such a conclusion about this states compliance with its obligation may be unfair. (b) Impact of extra-sectoral spending on the realization of ESC rights The resources that a state should use for the progressive realization of ESC rights are not limited to those devoted to specic sectoral ministries or agencies (e.g. Ministry of Health or Education). In fact, often the policy interventions required, such as the creation of access roads to overcome obstacles of physical accessibility to essential services for people living in remote rural areas, need to come from other budget lines. Therefore, as a World Bank study on government health expenditure and health outcomes points out: even if extra funds are applied extensively to health care (e.g. more staff at hospitals, adequate stocking of medications), but complementary services, both inside and outside the health sector, are not there (e.g. lack of roads or transportation to hospitals and clinics, subsidized prices for medication, etc.) the impact of extra government health expenditures may be little or none (Bokhari et al., 2007: 258).22

Downloaded from http://jhrp.oxfordjournals.org/ at Fundao Getlio Vargas/ RJ on August 13, 2012

22

For an example outlining the impact of the lack of adequate spending on infrastructure for education and health in rural areas, see Behrman et al. (2002: 20 21).

Eitan Felner 414

(c) Regressive patterns of social spending In many countries where the poor are deprived of primary health care and basic education, the state spends most of its social spending on the non-poor. As a study on basic social services observed: More is spent on highly specialized hospital care than on basic health care, even though substantial numbers of people have no access to the most basic health clinic. The same applies to the continuing emphasis on secondary and university spending in countries where most children do not complete even ve years of formal schooling. (Mehrotra, 1996: 13) Therefore, a monitoring exercise that looks only at the levels of expenditure for a particular social sector, without looking at the composition of that expenditure, may reach a misleading conclusion about the use of maximum available resources for the progressive realization of ESC rights. (d) Inefciency in the use of resources Increasing the allocation of resources will not meet the obligation of progressive achievement if these resources are not used efciently.23 One obvious form of inefciency involves corruption. Another form of inefciency involves the frequent tendency of government agencies to overspend on expenditure items towards the end of a budgetary year in order to prevent having budget lines reduced the following year. A Proposed Toolkit Before setting out the toolkit proposed to monitor the obligation of progressive realization, some preliminary comments should be made. First, the inextricable link between the obligation of progressive realization and the use of maximum available resources has clear implications for any monitoring method meant to assess compliance with this obligation. Because of this link, it is not sufcient for any monitoring exercise just to assess whether a state has made progress over time in the realization of any right. To comply with its human rights obligations, the pace of progress has to be reasonable in light of the states available resources. The crucial and difcult question is how to determine what levels of progress on ESC rights would be sufcient for any country to comply with the obligation of progressive realization, given the level of economic growth that a given country has had over a period of time. Any proposed methodology should address this crucial issue. Second, there is a need to use more than one method for monitoring the obligation of progressive realization. This is not only because no single

23 As the Limburg Principles point out, The obligation of progressive achievement. . . requires effective use of the resources available (The Limburg Principles on the Implementation of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, UN doc. E/CN.4/ 1987/17, para 23; see also para 27).

Downloaded from http://jhrp.oxfordjournals.org/ at Fundao Getlio Vargas/ RJ on August 13, 2012

415 Monitoring Progressive Realization of ESC rights

assessment tool can capture the multiple policy factors that affect the level of resources that a state devotes to the progressive achievement of ESC rights. It is also because the monitoring tools need to be adapted according to the purpose and scope of the monitoring exercise, which in turn would depend on the type of user. For example, the quantitative tools that a human rights monitoring body would use to monitor compliance with an International Treaty would probably be very different from those used by an international development agency interested in assessing human rights progress by individual countries in order to determine its aid priorities. The use of quantitative tools by a government committed to integrating human rights principles into its public policies would be quite different from those used by a human rights advocacy NGO that is interested in exposing, and perhaps naming and shaming, a government that is unwilling to adopt policies in line with its human rights obligations. In the choice of tools there is a need to recognize that there is often a tradeoff between comprehensiveness and simplicity: the more detailed and comprehensive the methods, in order to fully capture the complexity of the issues related to resource allocation and progressive achievement, the less simple they typically are to use and to convey to non-experts, and vice versa. In an effort to strike a balance between simplicity and comprehensiveness, and taking into account that different users and monitoring purposes call for varying degrees of complexity in the tools used, I rst propose a basic framework for monitoring the obligation of progressive realization, which consists of a set of simple methods that could potentially be used by virtually anybody interested in monitoring ESC rights. This basic framework is then complemented by the description of some more sophisticated tools that have been developed in recent years by various researchers or used by civil society organizations. The relevance of each of these tools will vary according to circumstances, depending on the purpose and scope of the monitoring exercise for which they are put to use and the level of technical expertise of the potential users. Basic Framework The basic framework proposed to monitor the progressive realization of ESC rights consists of three consecutive and complementary steps, each one containing some simple methods. These methods are meant to complement and build on the existing approaches described in the previous section. These tools are user-friendly and lend themselves to be displayed in visual forms, thus maximizing advocacy capacity. At the same time, these tools are not meant to give a comprehensive picture, nor provide conclusive evidence, of a countrys compliance with these obligations. Rather, they ag some possible concerns which could be subsequently assessed by other methods. For instance, these methods could help monitoring bodies to identify some specic concerns that could serve as

Downloaded from http://jhrp.oxfordjournals.org/ at Fundao Getlio Vargas/ RJ on August 13, 2012

Eitan Felner 416

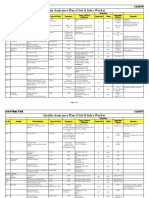

a basis for a more substantive dialogue with the relevant State Party. Or they could be used by an NGO as an initial assessment in a more comprehensive research effort, which may include using methods that are technically more sophisticated, such as those briey discussed later in this article. Step 1: Comparing Social Indicators with GDP Per Capita This rst step enables one to measure human rights progress over time according to the level of a countrys development. The simplest method is to compare a social indicator over time, such as primary school completion rates or child malnutrition (as a proxy for the enjoyment of some aspects of a specic right) with GDP per capita (as a proxy for available resources). This method is helpful in cases where a country experiences a reversal in a social indicator during a period of signicant economic growth, as illustrated in Figure 1. In these circumstances, such reversals would indicate, prima facie, a state is not complying with its obligation to progressively realize key rights according to available resources.

Downloaded from http://jhrp.oxfordjournals.org/ at Fundao Getlio Vargas/ RJ on August 13, 2012

Figure 1. Primary completion rate versus GDP per capita Jamaica (1990 2005).

Nevertheless, cases in which social indicators actually deteriorate over time are relatively rare. In fact, most countries make (more or less) progress over time.24 In such cases, comparing changes in a single country over time of a

24 For instance, among 117 developing countries for which data are available, 80 countries increased their net primary enrolment rates from 1990 to 2005, while only 36 countries decreased their primary enrolment rates over this period (one country maintained the same rate). Over the same period, 120 countries decreased their rate of child mortality while the rate increased in only 17 countries (United Nations Millennium Development Goal Database (http://millenniumindicators.un.org).

417 Monitoring Progressive Realization of ESC rights

Downloaded from http://jhrp.oxfordjournals.org/ at Fundao Getlio Vargas/ RJ on August 13, 2012

Figure 2. Primary completion rate versus GDP per capita Tanzania (1990 2006).

relevant outcome indicator against changes in GDP per capita is not very helpful. Its limitations become apparent when looking at Figure 2. With these data alone, it is not possible to assess whether Tanzanias progress in primary completion rates between 1990 and 2006 is adequate to the level of economic growth experienced by the country during the same period. When progress is made, a different method is necessary to determine whether this progress is adequate or too slow relative to the change in resources. One such method is to compare the performance of the focus country with that of similar countries. This can be done using a crosscountry comparison of per capita incomes with social indicators.25 Such comparisons of the performance of the focus country can provide an objective benchmark against which actual performance may be judged. As an illustration, comparing Figure 3 with Figure 4, the Center for Economic and Social Rights showed that while India had an income growth of 58 percent between 1995 and 2005 one of the highest in the world its child mortality rate reduction during the same period was one of the lowest in South Asia (CESR, 2008). Indias underperformance in reducing child mortality is

25 When making such a comparison, one may want to control for other factors that could have an impact on the social outcome, independent of GDP. For instance, when studying the effect of governance on poverty, Mick Moore controlled for population density, guring that a country with a higher population density can more efciently provide services than a larger country with lower population density (Moore, 2003). In a similar study, Frances Stewart controlled for whether or not a country was heavily dependent on oil extraction for its economic well-being (Stewart, 1985). To avoid controlling for a whole set of possible relevant factors such as weather/climate, conict spillovers, and cultural beliefs which would require making the quantitative tools proposed here more complex it is possible to just make comparisons across countries of the same geographic region, a standard practice used as a simple alternative to controlling for multiple potentially relevant factors.

Eitan Felner 418

Downloaded from http://jhrp.oxfordjournals.org/ at Fundao Getlio Vargas/ RJ on August 13, 2012

Figure 3. Decrease in under-ve mortality rates 19952005.

Figure 4. GDP per capita PPP* growth 19952005. *Purchasing Power Parity (PPP) is a method to calculate exchange rates which is commonly used to compare countries standard of living or per capita GDP.

apparent when compared with Bangladesh. Despite a signicantly lower level of income and lower economic growth than India, Bangladesh had a markedly greater reduction in under-ve child mortality rates. These differences matter. Had India matched Bangladeshs rate of reduction in child mortality over the past decade, 732,000 fewer children would have died (UNDP, 2005). Since this method only shows the level of progress made over a given period of time and not the overall current level of enjoyment with regard to that social indicator it should be used together with another method that can compare the most recent data about indicator levels with the levels of GDP per capita. Such a comparison may reveal that countries that had made relatively good progress in the realization of a relevant right are still lagging behind when compared with other countries with similar development levels, or even poorer countries, in the same region. For instance, Figure 5 compares the Education for All Development Index (an index of key

419 Monitoring Progressive Realization of ESC rights

Downloaded from http://jhrp.oxfordjournals.org/ at Fundao Getlio Vargas/ RJ on August 13, 2012

Figure 5. Education for all index and GDP per capita, Latin America and the Caribbean, 2006.

education outcomes, developed by UNESCO as a proxy for the status of education in a given country) with the level of economic development for countries in Latin America.26 This gure clearly shows that relative to its level of economic development, Guatemala is under-performing in education outcomes when compared with other countries in the region, even lagging behind poorer countries such as Bolivia, Paraguay, and Honduras. Step 2: Analysis of Resource Allocations27 Consistent with the principle of national sovereignty, human rights law affords states a margin of discretion in selecting the appropriate measures necessary for realizing ESC rights.28 This includes making decisions on the use of resources at their disposal and setting budget priorities accordingly. However, the extent of a states discretion is limited by the human rights obligations it has committed to uphold.29 It is therefore appropriate for any monitoring effort to assess the reasonableness of the budgetary priorities in light of human rights standards. Analysing the magnitude, composition, and distribution of resources allocated to social sectors (e.g. the educational or health systems) is crucial for

26 27 28 29 This Index combines four basic dimensions of education: universal primary education, adult literacy, the quality of education, and gender parity. This section is partially based on Felner (2008). Maastricht Guidelines, footnote 8, para. 8. See, for example, CESCR. General Comment 12, footnote 13, para. 21; CESCR. General Comment 14, footnote 15, para 53.

Eitan Felner 420

assessing whether a state is devoting the maximum of its available resources to the progressive realization of ESC rights. An in-depth budget analysis is optimal for this purpose. Some pioneering NGOs have made important inroads in this regard, integrating rigorous budget analysis into a human rights framework.30 However, most human rights activists do not have the technical skills, time, or resources required to undertake complex budget analysis. Nevertheless, it is possible to use simple quantitative tools to assess the adequacy and distributional equity of resources devoted to the realization of ESC rights. First of all, a snapshot of the extent of a states commitment to a particular economic and social right can be obtained by looking at the proportion of the GDP of that state allocated to the relevant social sector. Let us take, for example, the right to education. The relevant indicator would be the primary education expenditure ratio, measured by the expenditure on primary education as a percentage of GDP. Imagine that, during Step 1 of the proposed framework, one nds that in the focus country primary completion rates are lower than those observed in other countries of the same region with similar or lower levels of GDP per capita. In such a case, if this country has a lower primary education expenditure ratio than other countries in the same region with similar needs and overall income, this would suggest that the focus country is failing to comply with its obligation to devote the maximum of available resources to the progressive achievement of the right to education since it is devoting a smaller proportion of GDP to primary education than these other countries, despite having a larger proportion of its children that do not enjoy this basic right. In turn, the level of public spending on basic social services is determined by a set of policy decisions, ranging from scal policies to the distribution of resources within a specic social sector. Three key policy decisions are particularly relevant: (1) the level of aggregate public expenditure (as a proportion of GDP); (2) the scal priority assigned to the relevant social sector (e.g. the education or health sector); and (3) the priority of basic social services within total social sector expenditure. A set of three ratios, adapted from a set of ratios proposed by the United Nations Development Program to analyse public spending on human development (UNDP, 1991, 1996), can help identify which of these policy decisions may generate a bottleneck in the nancing of essential services, thereby hindering the realization of ESC rights. UNDP suggests that these ratios are a powerful operational tool that allows policy makers who want to restructure their budgets to see existing imbalances and the available options (1991: 39). However, these ratios could also be a powerful monitoring tool allowing human rights advocates to identify when

Downloaded from http://jhrp.oxfordjournals.org/ at Fundao Getlio Vargas/ RJ on August 13, 2012

30

See footnote 10, above, for examples of such organizations.

421 Monitoring Progressive Realization of ESC rights

A government appears not to raise sufcient revenues to adequately fund competing needs; A government devotes insufcient resources to an area related to a specic right (education, health, food security, etc.); A government allocates disproportionately few resources to budgetary items within a social sector that should be a priority from a human rights perspective. (e.g. disproportionate spending on tertiary versus primary education, or on metropolitan hospitals as opposed to rural primary health care services); There are manifest disparities in the allocation of resources for a particular sector among specic groups or regions. Figure 6 uses the right to education to illustrate this set of expenditure ratios. The gure shows that the public expenditure ratio is the result of three expenditure ratios the Public expenditure ratio, the Education allocation ratio, and the Primary education priority ratio which reect three key decisions in the budgeting process. (a) Public expenditure ratio government share of GDP This ratio is the percentage of national income (using GDP as a proxy) that goes into public expenditure. It reects the size of a governments budget in relation to the size of its economy. It also indicates the size of the pie of resources a government has at its disposal to undertake all its functions. Since taxation is generally a major funding source for public expenditure, this ratio often depends largely on taxation levels. Although possibilities for

Downloaded from http://jhrp.oxfordjournals.org/ at Fundao Getlio Vargas/ RJ on August 13, 2012

Figure 6. Expenditure ratios.

Eitan Felner 422

raising taxes may partially depend on state capabilities, they also depend to varying degrees on state policy decisions. If this ratio is too high and a large proportion of national income is drawn into the public sector, this might depress private investment and restrict economic growth (UNDP, 1991: 40), which could jeopardize the sustainability of ESC rights realization.31 If this ratio is too low, the state is weakened, making it difcult to adequately provide resources for many competing and often essential functions. A persistently low ratio can reect a structural problem, for instance, an economic elite able to prevent any substantial tax increases, 32 or a widespread pattern of tax evasion,33 that could seriously impair a states ability to realize its ESC rights obligations. (b) Education allocation ratio education share of government spending This ratio refers to the percentage of public expenditure allocated to education. It reects the relative priority given to education among competing budgetary needs. The extent to which a low education allocation ratio is problematic from a human rights perspective depends on the circumstances. The level of enjoyment of a specic right is crucial. A state where most of the population is literate and practically all children enjoy access to primary education might be justied in reducing its education spending and re-allocating funds to another social sector with pressing needs. Since a state has a margin of discretion to determine its budgetary priorities, it could still be legitimate to allocate relatively more resources on housing or on health than on education, even if these other sectors are not worse off than the education sector. However, if there is a high level of illiteracy or great disparities in the primary school completion rates of boys and girls, a low education allocation ratio would not be justied. Thus, this ratio can help expose and challenge cases in which a government might make spurious arguments about lack of sufcient resources to discharge its duty of progressive achievement when, in fact, the problem is not resource constraints but rather the preference of that government to use available resources for extravagant spending, squandering state resources in unnecessary areas.34

31 32 33 The relation between promoting ESC rights and promoting economic growth is a complex one, worthy of separate analysis, but it is beyond the scope of this article. See for instance, Center for Economical and Social Rights (CESR) and Instituto Latinoamericano Para Estu dios Fiscales (ICEFI) (2009). In its Concluding Observations on Georgia, the Committee on the Rights of the Child recognized the impact of tax evasion on the issue of maximum available resources. See Committee on the Rights of the Child. Georgia. CRC/C/97 (2000) 18, para 94. One example was analysed by the Kenya National Commission on Human Rights in its report Living Large: Counting the Cost of Ofcial Extravagance in Kenya (2005). This report showed that Kenyas government has spent more than $12 million on new cars for

Downloaded from http://jhrp.oxfordjournals.org/ at Fundao Getlio Vargas/ RJ on August 13, 2012

34

423 Monitoring Progressive Realization of ESC rights

The relevance of this ratio for monitoring compliance with the obligation to devote maximum available resources is illustrated by the fact that, as a study about the work of the Committee on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights noted, this Committee sometimes expressed satisfaction when a State Party began giving priority to the realization of these rights instead of allocating resources to public beautication projects (Sepulveda, 2003: 335). (c) Primary education priority ratio primary education share of education spending This ratio, which refers to the percentage of the total education expenditure allocated to primary education, reects priorities within a given educational system. The interpretation of low levels of this ratio will depend once again on the examination of circumstances. Countries that have already achieved high standards of primary education may be justied in prioritizing higher education levels.35 However, in countries where a signicant proportion of the population is illiterate or many children are deprived of the most basic forms of education, a low primary education priority ratio could be interpreted as a violation of a states minimum obligations regarding the right to education. This is precisely the case in those countries where many of the poor are deprived of basic education or primary health care, yet the state spends most of its social spending on the non-poor. The combination of having a signicant proportion of the poorest population deprived of minimum essential levels of ESC rights, while regressive spending patterns disproportionately benet more afuent groups, is quite common in developing countries.36 How to use the ratios: It is possible to determine if ratio levels in a given country are relatively high or low by comparing the levels with a reference point or objective standard against which it can be judged. Specically, ratio levels can be compared with the following: (i) State commitment, such as a constitution, national plans, or political agreements. For instance, in its 1996 Guatemala Peace Agreements, the

senior government ofcials enough money to send 25,000 children to school for eight years. This was, for instance, the case of Vietnam. A cross-country study of current spending on basic social services found that although this country had low spending on basic education as a proportion of its education budget, it had a long history of investment in education, and enjoyed high literacy and low dropout rates, as well as near-universal primary school enrolment. Therefore, the researchers concluded that spending on education appears to have been increasingly devoted to higher levels of education without impeding primary level enrollments (Harrington et al., 2001: 194). A regressive pattern of spending may also be considered a covert form of discrimination where, for example, investments disproportionately favor expensive curative health services which are often accessible only to a small, privileged fraction of the population, rather than primary and preventive health care beneting a far larger part of the population (CESCR, General Comment 14, footnote 15, para. 19).

Downloaded from http://jhrp.oxfordjournals.org/ at Fundao Getlio Vargas/ RJ on August 13, 2012

35

36

Eitan Felner 424

government of Guatemala committed itself to step up public spending on education as a proportion of gross domestic product by at least 50 per cent over its 1995 level (Presidential Peace Commission, 1996). (ii) The level of the same ratio in other countries in the same region.37 (iii) A suggested standard based on empirical evidence. For instance, when originally proposing its set of ratios as a means to analyse public spending from a human development perspective, UNDP suggested what the ideal levels of these ratios should be (UNDP, 1991: 40). Similarly, the WHO has set a global minimum target of ve percent of Gross National Product (GNP) for health expenditure (World Bank, 1993: 312, quoted by Chapman, 2007: 157). Step 3: Analysis of Expenditure Per Capita An analysis of the overall resources allocated by a state to specic social sectors has to be complemented by an analysis of the expenditure per capita on those sectors. Obviously, how much a state spends per capita on any sector depends not only on factors related to government policies and priorities (i.e. those reected in the ratios described in Step 2) but also on the level of economic growth (or contraction) and the size of the population two factors over which any government has, at best, only partial control. Therefore, since states only commit violations of ESC rights when their actions or omissions reect an unwillingness to comply with their human rights obligations, and not when they are unable to carry them out,38 the level of expenditure per capita that any state spends on areas such as education or health cannot in itself serve as an indicator of compliance (or lack thereof) in the progressive realization of ESC rights. Using this indicator for such a purpose would be unfair towards poor countries since per capita expenditure is closely related to a countrys level of income and, therefore, it would necessarily lead to the conclusion that the richest countries are in compliance with their obligations, while the poorest are not. Nevertheless, the analysis of per capita expenditure is still crucial for monitoring purposes. Such an analysis can help identify common policy problems that may hinder the progressive achievement of these rights. It can also help to determine the types of policy strategies a government should adopt to address these problems. For instance, the case of a state with a low level of nancial commitment to a social sector (reected in low levels of the ratios

37 For instance, the Committee compared the money spent by a state on the implementation of a specic Covenant right and that which is spent for the same item by other states with the same level of development to assess its compliance with its obligation of using the maximum available state resources. For example, when examining the Second Periodic Report of the Dominican Republic, the Committee noted with great concern that State expenditure on education and training as a proportion of total public spending was less than half the average in Latin America (Sepulveda, 2003: 317). Maastricht Guidelines, footnote 8, para 13.

Downloaded from http://jhrp.oxfordjournals.org/ at Fundao Getlio Vargas/ RJ on August 13, 2012

38

425 Monitoring Progressive Realization of ESC rights

described in Step 2) that also has a low level of expenditure per person in that sector, suggests a violation of that states obligation to devote its maximum available resources to the progressive achievement of the relevant right. As unit costs are not a major constraint to increasing overall spending on the sector, progressive achievement of the relevant right could reasonably have been within the states reach if it had shown a stronger commitment to devoting resources to that purpose. On the other hand, the case of a state with a low level of expenditure per person in a social sector, despite a high level of nancial commitment to that sector (reected in relatively high per cent of expenditure on that sector as a portion of its GDP), would suggest that a key strategy that such a state should adopt to raise the level of realization of ESC rights is an effort to accelerate its economic growth.39 An analysis of expenditure per capita could also help reveal deeply embedded inefciencies in the use of resources which, as we saw above, could amount to a failure of discharging the obligation of devoting maximum available resources. Thus, due to an inefcient use of resources, a state may in some cases actually be spending too much money per person on a social sector (such as health) or essential service (such as primary schooling). This phenomenon is well illustrated by a study on primary schooling in Sub-Saharan Africa that shows that in most of the countries with low school enrolment, despite the overall adequacy of their spending allocation (as measured by the public spending on primary education as a percentage of GDP), high unit costs of schooling (measured by the amount of money spent per pupil in the primary school system) were a critical constraint on the ability of governments to universalize primary education (Colclough et al., 2003). For instance, Ethiopia was spending 1.7 percent of its GDP on primary education nearly the average in Sub-Saharan Africa (1.9 per cent) but it spent the equivalent of almost 40 percent of per capita income on each pupil (while the average for Sub-Saharan Africa was only 13.6 percent). Given this exorbitantly high level of unit cost of schooling and taking into account Ethiopias school enrolment rates, the researchers of this study calculated that achieving universal public education would have required an allocation of around seven percent of GDP annually, a virtually impossible commitment to expect from such a poor country (Colclough et al., 2003: 98 100). Additional Tools Although the basic methodological framework may be sufcient for the needs of some monitoring exercises, some users who have sufcient technical

39 At the same time, if the gap between how much this state spends per capita on education or health and how much it should spend to ensure the equal enjoyment of ESC rights is too large, this would indicate that such a country cannot guarantee the enjoyment of these rights without international assistance.

Downloaded from http://jhrp.oxfordjournals.org/ at Fundao Getlio Vargas/ RJ on August 13, 2012

Eitan Felner 426

skills and are undertaking more ambitious monitoring projects may want to use more sophisticated monitoring methods. The following are some methods developed in recent years by researchers from different disciplines. While some of these methods were specically designed to monitor the obligation of progressive realization or, more generally, the various types of obligations pertaining to ESC rights others were originally designed for other purposes, but could easily be adapted for monitoring progressive realization.

Downloaded from http://jhrp.oxfordjournals.org/ at Fundao Getlio Vargas/ RJ on August 13, 2012

Alternative Methods to Compare Social Indicators with GDP Per Capita Several methods have been used or proposed to compare social indicators with GDP per capita. Many of these tools add some dimension of complexity to the simple tools presented in the basic framework. The following are just two illustrative examples. One method compares the absolute levels of a social indicator and the GDP per capita of several countries at different points in time. As Figure 7 shows, this enables one to get information simultaneously about the pace of progress made by several countries with regard to that indicator over a given period of time (against the level of GDP growth) along with the absolute levels of those indicators, thereby combining the type of information obtained by Figures 3, 4, and 5.40

Figure 7. Child mortality rate versus GDP per capita (19902006). Sub-Saharan Africa selected countries. Authors design based on WDI 2008.

Figure 7 shows that while most countries in Sub-Saharan Africa have made progress in reducing their child mortality rates from 1990 to 2006, Kenya increased its child mortality rates. As a result, at the end of this period,

40 This method is taken from a report produced by the Economic Commission for Latin America, where it is used with other indicators and for different purposes (ECLAC, 2001: gure IV.4b)

427 Monitoring Progressive Realization of ESC rights

Kenya had levels of mortality rates similar to poorer countries such as Malawi and Tanzania, but still lower levels than richer Nigeria. Another method, proposed as part of an effort to build a composite index of ESC rights fullment, consists of using an Achievement Possibility Frontier (APF) approach to measuring ESC rights fullment. This frontier determines the maximum level of achievement for any ESC right at a given per capita income threshold, based on the highest level of the indicator historically achieved by any country at the same per capita GDP (Fukuda-Parr et al., 2008). As the proponents of this approach point out, the main advantage of the APF approach is the possibility of assessing a states fullment of its obligation of progressive realization based on the level at which a country at a given per capita GDP could perform. This clearly enables one to obtain more accurate results regarding the compliance of a given country with its obligation of progressive realization than the simpler tool illustrated in Figure 5, which assesses a states fullment of this obligation based only on a comparison with the performance of other countries of the same level of development at a particular point in time. To illustrate the difference between approaches, Figure 5 showed that using this simple method, Peru appeared to fare relatively well in 2005 in terms of its obligation of the progressive realization of the right to education, having achieved better education outcomes (as reected in the Education for All Index) than other countries with similar levels of GDP per capita. However, using the APF approach could perhaps reveal that in the past one or more countries with the same per capita GDP level that Peru had in 2005 were able to achieve signicantly better levels of education outcomes than Peru. This would suggest that given this level of economic development, Peru could perform better in the realization of this right, a conclusion that could not be obtained by using the simpler method. At the same time, as the proponents of the APF method acknowledge, a key drawback of this method is that it is not as easy to grasp as the simpler method, which makes it more opaque to policy makers (Fukuda-Parr et al., 2008: 20) and potentially less powerful as an advocacy tool.41 Budget Analysis As mentioned above, some pioneer civil society organizations around the world have begun to integrate rigorous budget analysis into a human rights framework. Such analysis enables organizations to identify and challenge different types of leakages and bottlenecks in the budgeting process that prevent the allocation of the maximum available resources to progressive

41 For other methods that compare social indicators with economic growth, see references from footnote 25 above, and Figures 8 and 9 and the accompanying explanation in a study on Pakistan by Easterly (2003).

Downloaded from http://jhrp.oxfordjournals.org/ at Fundao Getlio Vargas/ RJ on August 13, 2012

Eitan Felner 428

realization, and which cannot be detected using the simple tools suggested in the analysis of resource allocation and expenditure per capita set out in the basic framework. A case study on the right to health in Mexico, carried out by Fundar, a Mexican centre for analysis and research, illustrates how budget analysis can be a very powerful tool in helping to assess a governments compliance with its ESC rights obligations (including the obligation of progressive realization) and holding a government accountable for these commitments.42 For instance, examining the gap between budgeted spending and actual spending, the study found that while the Ministries of Finance, Tourism, and Foreign Affairs each spent more during the course of the year than was allocated in the budget, this was not the case with the Ministry of Health. From this, Fundar was able to deduce that when extra resources became available, they were not allocated to the health programme (Fundar et al., 2004: 37 38). Moreover, comparing the budget for specic health programmes with other programmes throughout the budget, the Fundar study found that the additional spending in the Ministries of Finance, Tourism, and Foreign Affairs, above and beyond the amount originally allocated in the budget, was 2.3 times the total budget of a health care programme aimed at 10 million Mexicans in extreme poverty (ibid: 37 39). These ndings raise questions about Mexican commitment to use the maximum of available resources for the progressive achievement of ESC rights. Fundar also examined the composition of the health budget. Mexico has two parallel health systems: the social security system that provides health care to individuals who are legally employed and their families and the public health system that provides health services to people who lack formal employment and are therefore not eligible for social security. In the study, Fundar compared what percentage of the total budget goes to each of the two systems and found that although each of them roughly served half of the Mexican population, the social security system was allocated nearly double the spending of the public health system. Such inequitable spending patterns, where the people lacking formal employment and are therefore less likely to be able to afford private health services are those that benet less from state spending on health services, could be interpreted as a clear violation of the requirement to use the maximum available resources for the progressive achievement of ESC rights. The Analysis of Macro-economic Policies Balakrishnan and Elson (2008) have recently proposed a methodology to assess the effects of macro-economic policies such as scal and monetary policies, taxation, and international trade on the progressive realization of the peoples economic and social rights. On the basis of this methodology,

42 A detailed description of this case study can be found in Fundar (2004).

Downloaded from http://jhrp.oxfordjournals.org/ at Fundao Getlio Vargas/ RJ on August 13, 2012

429 Monitoring Progressive Realization of ESC rights