26 Woolterton Marinova Davis Stocker

Diunggah oleh

francoisedonzeau1310Deskripsi Asli:

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

26 Woolterton Marinova Davis Stocker

Diunggah oleh

francoisedonzeau1310Hak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Wooltorton, S. and Marinova, D. (Eds) Sharing wisdom for our future.

Environmental education in action: Proceedings of the 2006 Conference of the Australian Association of Environmental Education

Chapter 26 Adopt a Beach: Educational Praxis for Sustainability John Davis and Laura Stocker Institute for Sustainability and Technology Policy, Murdoch University 1. Introduction In this paper we analyse the role of coastal stewardship as educational praxis for sustainability, using the Adopt a Beach programme as an example. Marine and coastal stewardship has become a popular practice among coast-dwelling Australians, for many of whom the beach is a defining feature in their identity. The coast forms a legal and biophysical commons so it offers a portal into an ethical framework for caring for our shared environmental heritage and legacy. We suggest that stewardship is an ethical framework which models environmental citizenship in terms of responsibility for place and accountability to future generations for our current actions. The scope, scale and aims of Adopt a Beach programmes in their various forms are examined and we present two detailed case studies which show their potential for developing capacity for environmental stewardship. At the core of any transition from un-sustainability to sustainability lie not technologies nor even institutional arrangements, but values and worldview (Barns, 1991; Reed, 2006). In spite of our heavy investment in innovative environmental technologies, insufficient attention has been paid to development of world-views and ethical praxis which give priority to ecological sustainability. Stewardship provides a creative alternative to the dominant paradigm of private ownership and consumption on one hand and apathy towards public good on the other hand. Sustainability can be described as the re-ordering of the relationships between humans and the non-human elements of our world in ways that make possible ecological integrity and human fulfilment (Bell, 2003: vi). The UN Decade of Education for Sustainable Development emphasises the importance not just of good science for sustainability education but also ethical principles and attention to the cultural dimension and quality education (UNESCO, 2006) Education for sustainability is therefore potentially transformative in the sense that it seeks to shape values and equip the learner to move to a more sustainable way of living. The Western Australian State Sustainability Strategy describes four phases of education for sustainability: Awareness raising Does it matter to me? Shaping of values Should I do something about it? Developing knowledge and skills How can I do something about it? Making decisions and taking action What will I do? Government of Western Australia (2003: 245)

Education for sustainability which takes place in the framework of stewardship of place brings together the sciences of the environment, culture of place and ethical values required for the transition to a more sustainable society.

239

Wooltorton, S. and Marinova, D. (Eds) Sharing wisdom for our future. Environmental education in action: Proceedings of the 2006 Conference of the Australian Association of Environmental Education

Stewardship may simply be defined as the management of something on behalf of another, or as Rodin (2000: 28) neatly reformulated the classical Christian use of stewardship, handling with integrity the resources of another. The notion of accountability is introduced by this definition. Coyles (2005: 34) description of environmental ethics as what people do on a day-to-day personal level to benefit the environment explains it in plain language. The role of steward is closely linked to the idea of trustee. A stewardship ethic values taking care of the present and future welfare of natural and built objects and places, and of people too (O'Riordan, 1998: 103). In the process of taking care two key elements of stewardship are clear: it is both action and an ethical position. We suggest it is a form of praxis1 in that while the ethical dimension informs the action, the precise nature of what is required in a given situation needs to be explored in the community, in a place, through the process of implementation, conditioned by the circumstances (Freire, 1992). Stewardship ethics have been criticised for their anthropocentrism by those who argue for a more eco-centric eco-philosophy (Saner and Wilson, 2003: 6). However, the present discourse about global climate change provides a good example of why, in current times, the stewardship concepts offer an option even amenable to ecocentric concerns. A core issue for international environmental politics in 2006 is whether there will be universal international acceptance of anthropogenic causes of climate change and then acceptance of responsibility for the problem and commitment to ameliorate or reverse it. Similarly, an interpreter at a Dolphin Discovery Centre eloquently expressed: Dolphins dont need our management to exist, but we have such a huge impact on them and their habitat that we need to manage our impacts. The role of steward is needed to ensure the current and future integrity of the natural world in the face of local and global threats from the humans within the ecosystem. Adopt a Beach programmes described in this paper provide a case study in education for stewardship. The adoption metaphor expresses similar meanings to stewardship and enables students to explore some of the ambiguity of stewardship, which also corresponds to the existential dilemmas of human society. In particular, the potential for paternalism, arrogance, and control needs to be seen against awareness of our dependence on the ecosystem in which we live and the need to recognise our place as fellow members of the community of life (Leopold, 1949). 2. Stewardship of Place We have become very familiar with the saying, think global, act local. Cairns (2003: 2) puts it this way: there must be a global strategy for sustainability, but also a strategy that considers the unique issues and ecosystems for each bioregion. This suggests that place responsiveness must be integral to any strategy and any education for sustainability, developing the capacity of citizens/the community to relate the specifics of a particular place to the wider issues (for example climate change and biodiversity).

Praxis can be described as action which arises from moral disposition to act truly and rightly in situations where one does not truly know what is the proper form or technique for actions. Subsequent reflection on the activity then leads into an action-learning cycle (Smith, 1999). 240

Wooltorton, S. and Marinova, D. (Eds) Sharing wisdom for our future. Environmental education in action: Proceedings of the 2006 Conference of the Australian Association of Environmental Education

Place relationships are important in practice of environmental education (Cameron, 2003: 110) and even, in the formation of ethics (Smith, 2001). Leigh (2005) argues that the local experience and a locally grounded ethic provide the basis for effective response to the large global problems facing our time. Place-based education is hardly a new concept: historically, much childhood learning for life was inherently linked to place and daily practice, often including stewardship. However within the contemporary western schooling, place-based education is an attempt to re-contextualise learning. Place-based education in this sense has emerged as a significant pedagogy in the last 10 years with the aim of linking a school to its community and to the landscape in which it is located. It highlights the significance of place and related ethic values to the development of meaningful understandings. Place-based educators puts forward that by grounding education in the local community, students can see the relevance of what they are learning and become more engaged in the process of learning (Powers, 2004). It can be linked to Freires (1992) emancipatory notion of critical pedagogy. Freire argued that all people and learners exist in a situation, and emancipatory education helps them learn to perceive social, political and economic contradictions and to take action against the oppressive elements of reality (Freire, 1992: 17). Place-based education can also play a part in the transformational educational response to institutional and ideological domination (Gruenewald, 2003). At the same time place-based education can also complement the widespread trend towards national standards-based education by embedding place-based curriculum into educational standards (Jennings et al., 2005). Powers (2004) reviews a range of place-based education programmes whose goals typically include: enhanced school connections with the community; increased understanding of the local places; increased connection to it; increased awareness of ecological concepts; enhanced civic engagement; enhanced stewardship behaviour; improvement of the local environment; improved academic performance; and better use of the schoolyard habitat as a teaching space. What is significant about the model, however early a conceptualisation, is the role of stewardship in linking understanding of place to healthier communities, via both increased skills and changed attitude or feelings. 3. Beach Adoption Programmes When a group adopts a beach it becomes a focus for stewardship and learning, and the group provides a service to the wider community on whose behalf, inter alia, they act. Programmes which use the Adopt a beach label can be found in the United Kingdom, the United States of America, the Republic of South Africa and New Zealand. Table 1 lists some of the programmes found by Internet search using the English language. Many of these programmes are based around litter removal or cleanup programs. The clean-up programmes range from one to four or more times per year. The educational component of beach clean-up events rests in both the experiential element of being on the coast and immersed in the environment, and an analytical element in which participants sort, catalogue and quantify the collected

241

Wooltorton, S. and Marinova, D. (Eds) Sharing wisdom for our future. Environmental education in action: Proceedings of the 2006 Conference of the Australian Association of Environmental Education

litter. Sponsoring organisations assist by providing guidelines and sometimes equipment to assist this process and even collecting data. Figure 1: Change theory for place-based education: a working model (from Powers (2004)

Understanding of place (knowledge, experience) Opportunities for school/community interplay Skills to act (knowledge, practice)

Attachment to place (attitude)

Enhanced competence and self-efficacy

Civic engagement/Community participation/Stewardship (behaviour change)

Community and social capital broadens and deepens

Healthier social and natural communities

At the other end of the beach adoption spectrum are those who encourage or facilitate the adopting group to learn in depth about the beach, collect data and in some cases submit monitoring data to an environmental monitoring programme such as State of the Environment reporting (WESSA, 2005: 1). Examples of this type have operated in the UK, USA and South Africa (Table 1). In Western Australia, with a number of schools interested in adopting-a-beach in 1997, the South-West Coastal Management Coordinating Committee received Coastwest/Coastcare funding for materials to assist schools to develop stewardship of a beach or section of the coast as environmental education. Three schools were quite involved, primarily due to the enthusiasm of individual teachers. The Coastwest/Coastcare grant funded limited production of an Adopt-a-Beach Manual which showed how teachers could relate coastal activities to their curriculum and

242

Wooltorton, S. and Marinova, D. (Eds) Sharing wisdom for our future. Environmental education in action: Proceedings of the 2006 Conference of the Australian Association of Environmental Education

included copies of sections of the newly published Marine and Coastal Monitoring Manual (MCMM). The MCMM was recently revised and in 2006 the Adopt-A-Beach manual is also being considered for revision. Some weaknesses of the manual in aiding placed-based education included the extra work it required of busy teachers. At a wider level, a steady ratcheting up of perceptions of risk and fears of public accident liability have imposed increasing levels of risk management protocols on school excursions, especially those involving water. At a meeting to discuss revising Adopt-a-Beach one teacher commented that schools have become allergic to activities involving water. Those meeting, who suggested that beach or coast-based education activities were difficult and therefore unattractive sparked this preliminary research into examples of schools which have Adopted-a-Beach. The two examples described here have a strong element of rehabilitation in their activities, whereas the Adopt-a-Beach Manual emphasizes observing, learning and litter removal. These cases also contrast to the example described by Netherwood et al. (2006) which was a stewardship project outside of Adopt-A-Beach, and broader in its scope. Table 1 Adopt-a-beach programmes around the world Country UK US US R.S.A. US US US US US Cook Islands US Virgin Islands US NZ Host/sponsor Marine Conservation Society Adoptabeach.com California Coastal Commission WESSA for Dept Env. Affairs & Tourism Alliance for the Great Lakes (Chicago) New Jersey Dept of Env. Protection Adopt a beach Hawaii- a Division of Hydromex Hawaii Inc. South Carolina Dept Health & Env Control, Ocean & Coastal Resource Mgmt Texas General Land Office Roratonga Environment Awareness Program Puerto Rico Natural Resources Dept Friends of Virgin Islands National Park Adopt a Beach (non-profit org) Washington State Min. for Environment Sustainable Management Fund Main activity 4 Litter surveys and collections /yr Advertising on rubbish barrels Year-round beach cleanup programme Cleanup, surveys & monitoring Beach assessment, water monitoring, litter collection & monitoring, revegetation Twice yearly litter collection Promote recycling of waste in Hawaii by selling sponsorship of collection bins Beach clean-up and keeping clean Remove debris from beaches & coastal waters, incr. public awareness about litter. Litter cleanup Keep beaches clean Primarily cleanup Training and Monitoring estuaries around Puget Sound with EPA. Funds Adopt-a Schemes

243

Wooltorton, S. and Marinova, D. (Eds) Sharing wisdom for our future. Environmental education in action: Proceedings of the 2006 Conference of the Australian Association of Environmental Education

4. Case Study: Mandurah Mandurah is a rapidly growing regional centre historically famous as a seaside and estuary resort. It has a Coastcare Committee and has organised its coastline into six distinct Coastcare zones of management. One of the nine staff responsible for environmental matters on the City Council is a Community Landcare Officer whose role is to educate and train on ways of living on the land. This person also works closely with the Coastcare Committee for issues related to coastal matters. The City produced an activity book called Sun, Surf and Sand to help children to make good decisions about their personal safety across a wide range of coastal environments while also addressing ethics of conservation of the coastal environment (Huston and Huston, 2000: 1). The cooperation between the City Council, community coordinating committee and local Coastcare groups and a school adopting its local beach attracted us to this case. The Community Landcare Officer and one Coastcare coordinator were interviewed about the role of adopting a specific place in environmental education. A local Coastcare coordinator in a semi-rural settlement described adopting a beach as: Identifying a bit of beach which you can access easily, or that you are very interested in and looking after it, and going through any channel you can to help you. In this case the coordinator homed in on a Primary School close to the beach for which he was responsible and asked if they wanted to do anything to do with the coast, marine studies, horticulture and then specifically suggested what about me coming in and organising a guest speaker and some brushing down on the beach? This suggestion was welcome and the first speaker made a good impression, so the programme got under way. The coordinator favours the rehabilitation element in education. I do it because its great for boys in education, who like to get out and be hands-on and physical and have meaningful activities I had a particularly bad Year 4 class one year [previous to Adopt-a-Beach] and that when I really kicked in the horticulture, outside-type activities My boys particularly [love it] because we get out there digging holes and using drills and lugging logs around. At the end of the day we are out of school, so thats fun to start with, but theyve actually had input into the community and theyve enjoyed themselves and theyve got ownership. Its theirs now. The learning experience described here is rich in its use of sensory pathways, embodied learning, sense of achievement and of course fun! The sense of ownership described is similar to the idea of trustee or steward described in the introduction to this paper. It is a theme that also emerged in discussions with participants the second case study. The teacher is a special needs teacher, who became involved in these education projects because they offered approaches suited to those students. Powers (2004: 26) observed that community-based learning emerged as very important for special needs students, even though this was not a focus of her study.

244

Wooltorton, S. and Marinova, D. (Eds) Sharing wisdom for our future. Environmental education in action: Proceedings of the 2006 Conference of the Australian Association of Environmental Education

5. Case Study: Adopt-a Coastline Joondalup, a metropolitan City Council in Western Australia organised its own Adopta-Coastline programme through which it assists local schools provide place-based environmental education. The programme has now been running for six years and in 2006 is considered by its coordinators to be a very effective programme, enabling students [to] participate in a lifelong learning project about caring for the coast into the future. Originating as a contract arrangement to educate students at a beach site, the programme now offers a structured programme. It brings together the States Curriculum Framework in the areas of Science, Society and Environment and Active Citizenship, and the Citys own Strategic Plan for lifelong learning and active citizenship in a programme of activities on a coastal site and back in the participating school. The City works with schools to deliver an eight-week programme during the second term of the school year. The class/es make four visits (fortnightly intervals) to a field site where they spend about 90 minutes. After an initial orientation, they examine survival of plants from the previous year, remove tree guards and over the remaining visits plant out tube seedlings. City staff participate in the activities on site by training the young children in transplanting techniques using seedlings raised jointly with the school over the preceding months. The staff also help students observe plants, animals and coastal processes, and are competent to answer the many questions that arise in the field. Each year applications are invited from schools and the programme has run for six years with 4 schools at a time. There are 64 schools in the City. The City Council staff adapt the programme to the needs of each school and the teachers involved: we can tailor it to the school it is really about active citizenship and taking part in their community. Teachers involved say the programme offers a thematic approach to all learning areas, across the whole curriculum. It is articulated with the curriculum especially because it articulates with the overarching statements. However, it is not just at the higher levels of outcome statements. Another teacher commented: We approached the experience initially from a Science or Science and Environment viewpoint. We incorporated Maths, English, T and E and Art. Values statements from all the learning areas supplied the main philosophical rationale or viewpoints. The breadth of learning areas which the teachers integrated into the programme exhibits the strengths of place-based education, yet the teachers themselves were not all familiar with this term. The teachers surveyed for this research suggested that learning outside the class is an important supplement to class activity and that education needs to allow multiple intelligences to emerge1. Organisers of Adopt-a-Coast observed that:

Howard Gardner (1983) coined this term when arguing that there is a spectrum of intelligences or capacities that enable to people to develop in life. Focus on the particular capacities measured by IQ testing have limited our understanding of intelligence, and in education has reduced opportunity for the 245

Wooltorton, S. and Marinova, D. (Eds) Sharing wisdom for our future. Environmental education in action: Proceedings of the 2006 Conference of the Australian Association of Environmental Education

Watching the children, the students, there is a social aspect to it where they were forming teams and some leaders emerged at such a young age, and took care of some of the other students coming to an agreement of who was going to do what job. Teachers educational goals for the programme included helping the students to become less aware of self and more aware of the environment. The picture that emerges from their comments is one in which the opening up of the students to the other brings together both human and non-human elements in their environment. 6. Restoration in Placed-based Education Leigh suggests that community-based restoration is beneficial to both community and environment in that: The practice brings communities together, promotes a conservation ethic, and develops a sense of place. By this action, humanity reconnects with the environment, often in meaningful ways, to heal a segment of an impaired earth. fosters an emotional commitment to a particular part of a landscape or seascape that often, inadvertently fosters a sense of ownership of the commons. (Leigh, 2005: 8) Among the students in both case studies a sense of ownership was evidenced in anecdotes of them admonishing their own family members to minimise their impact on the fore-dunes or telling their peers to not damage the vegetation because I planted some of those. This resonates with Leighs observation: An intuitive kindred, an extended family mind-set, emerges among restoration participants marked by a special psychological dimension, an emotional dimension, that these shared acts to improve the environment engenders. Environmental stewardship comes by igniting the passion of those that live in the community to choose environmental sustainability. community-based restoration mediates a new relationship with the natural world and transforms individual values into social values[helping to] forge collective purposes. (Leigh, 2005: 9) Community-based restoration allows the average citizen, by the immersion of all five senses, to experience th[e] complexity [of ecosystems] first hand. (Leigh, 2005: 11) The political, social and psychological value of restoration is very important along with its ecological value (Leigh, 2005: 12). It is a prime example of Civic environmentalism (Leigh, 2005: 12). Their experience in the coastal environment, embodied learning about coastal processes and enhancement of skills through the restoration activities help the students in this case study figure out who we are and who we need to be (Shellenberger and Nordhaus, 2004: 34). Empirical research has demonstrated the impact of place-based educational activities on affective qualities in students, indicating potential to reinforce stewardship (Coyle, 2005: 62)

development and expression of interpersonal, intrapersonal and emotional intelligence (among others) (Coleman, 1996: 38-9) 246

Wooltorton, S. and Marinova, D. (Eds) Sharing wisdom for our future. Environmental education in action: Proceedings of the 2006 Conference of the Australian Association of Environmental Education

Powers (2004) emphasises the links with the community in placed-based education. It would be interesting to see if the school groups could also have contact with some of the Coastcare groups. 7. What Can we Learn? The experiences of adopt-a-beach/coastline programmes suggest several lessons for place-based education programmes for coastal and marine education to be effective. There needs to be some form of institutional support outside of the individual classroom. These programmes are often inspired and driven by passionate or gifted teachers, but in order to be sustained beyond the tenure or extraordinary energy fund of that teacher the programme needs to be supported with logistics and resources. The case studies suggest that Local Government can play a significant role in providing this scaffolding to schools within its jurisdiction, sharing resources and helping manage risks of accident at low cost. Local government can provide resources for a number of schools in an ongoing programme. Access to resources also reduces the threshold of motivation and competence required of any individual teacher to commence activities on the beach. In relation to the model in Figure 1, the school case studies have relatively weak linkages to community groups, although the students do have opportunity to interact with council staff. If the students were also able to interact with a local service or stewardship group (e.g., Coastcare) it would constitute a strengthened civic engagement. Adopt-a-Beach approaches to place-based education provide opportunity for a wide variety of teaching objectives to be met simultaneously as they are relevant to the whole curriculum. Integration across the curriculum can be very powerful when learning synergies begin to emerge. The restoration component in the case studies enhanced embodied learning through performance of tasks which required teamwork. It also heightened awareness of human participation within the ecosystem, fostering the praxis of stewardship, a prerequisite for sustainability. The teachers and council staff involved in both case studies offered evidence of behaviour change which indicates increased stewardship. References Barns, I. (1991) Value frameworks in the sustainable development debate. Paper presented at the Ecopolitics V Conference, Sydney, April. Bell, S. J. (2003). Researching sustainability: Material semiotics and the Oil Mallee Project. Unpublished PhD Thesis, Murdoch University, Perth. Cairns, J. (2003). Integrating top-down/bottom-up sustainability strategies: An ethical challenge. Ethics in Science and Environmental Politics, 1-6. Cameron, J. I. (2003). Educating for place responsiveness: An Australian perspective on ethical practice. Ethics, Place and Environment, 6(2), 99-115.

247

Wooltorton, S. and Marinova, D. (Eds) Sharing wisdom for our future. Environmental education in action: Proceedings of the 2006 Conference of the Australian Association of Environmental Education

Coleman, D. (1996). Emotional intelligence. London: Bloomsbury Coyle, K. (2005). Environmental literacy in America. Washington: The National Environmental Education and Training Foundation. Freire, P. (1992). Pedagogy of the oppressed (M. B. Ramos, Transl.). New York: Continuum. Government of Western Australia. (2003). Hope for the future: The Western Australian State Sustainability Strategy. Perth: Department of Premier and Cabinet. Gardner, H. (1983). Frames of mind. New York: Basic Books. Gruenewald, D. A. (2003). The best of both worlds: A critical pedagogy of place. Educational Researcher, 32(4), 3-12. Huston, B., & Huston, J. (2000). Sun, Surf & Sand: Coastal safety education. Mandurah, Western Australia: City of Mandurah. Jennings, N., Swidler, S., & Koliba, C. (2005). Place-based education in the standards-based reform era conflict of complement? American Journal of Education, 112, 44-65. Leigh, P. (2005). The ecological crisis, the human condition, and community-based restoration as an instrument for its cure. Ethics in Science and Environmental Politics (ESEP), 3-15. Leopold, A. (1949). A sand county almanac. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Netherwood, K., Buchanan, J., Stocker, L. and Palmer, D. (2006). Values education for relational sustainability: A case study of Lance Holt School and friends. In Wooltorton, S. and Marinova, D. (Eds). Sharing wisdom for our future. Environmental education in action: Proceedings of the National Conference of the Australian Association for Environmental Education (pp. 250260). Sydney: AAEE. O'Riordan, T. (1998). Civic science and the sustainability transition. In D. Warburton (Ed.). In Community and sustainable development: Participation in the future (pp. 96-116). London: Earthscan. Powers, A. L. (2004). An evaluation of four place-based education programs. Journal of Environmental Education, 35(4), 17-31. Reed, B. (2006). Shifting our mental model "sustainability" to regeneration. Available on-line from http://www.integrativedesign.net/resources/articles.htm, accessed 01.12.2006. Rodin, R. S. (2000). Stewards in the kingdom: A theology of life in all its fullness. Downers Grove, Ill.: InterVarsity Press.

248

Wooltorton, S. and Marinova, D. (Eds) Sharing wisdom for our future. Environmental education in action: Proceedings of the 2006 Conference of the Australian Association of Environmental Education

Saner, M., & Wilson, J. (2003). Institute of Governance Policy Brief No. 19: Stewardship, good governance and ethics, 2006. Available on-line from http://www.iog.ca/view_publication.asp?publicationItemID=191, accessed 10.11.2006. Shellenberger, M., & Nordhaus, T. (2004). The death of environmentalism. Available on-line from http://www.thebreakthrough.org, accessed 10.11.2006. Smith, M. (1999). Praxis: The encyclopedia of informal education. Available on-line from http://www.infed.org/biblio/b-praxis.htm, accessed 04.12.2006. Smith, M. (2001). An ethics of place. Albany NY: State University of New York. United Nations Education and Scientific Cooperation Organisation (UNESCO) (2006). Education for Sustainable Development, United Nations Decade 2005 2014. Highlights on progress to date. Paris: UNESCO. Wildlife and Environment Society of South Africa (WESSA) (2005). Adopt-a-Beach Programme: Final report on WESSA's involvement. Kirstenhof, South Africa: WESSA, Western Cape Region. ____________________________________ Author Email: jkdavis@murdoch.edu.au

249

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- EcoliteracyDokumen8 halamanEcoliteracyMaria Kristel BendicioBelum ada peringkat

- Kopnina 2019 - Ecocentric EducationDokumen6 halamanKopnina 2019 - Ecocentric EducationLeon RodriguesBelum ada peringkat

- Environmental Education in Practice: Concepts and ApplicationsDari EverandEnvironmental Education in Practice: Concepts and ApplicationsBelum ada peringkat

- Environmental Education and Eco-Literacy As Tools of Education For Sustainable DevelopmentDokumen19 halamanEnvironmental Education and Eco-Literacy As Tools of Education For Sustainable DevelopmentRicardo RussoBelum ada peringkat

- Understanding Environment: Current Science July 2005Dokumen3 halamanUnderstanding Environment: Current Science July 2005AlexanderBelum ada peringkat

- Understanding Environment: Current Science July 2005Dokumen3 halamanUnderstanding Environment: Current Science July 2005apolloBelum ada peringkat

- REVIEWERDokumen17 halamanREVIEWERJorgeBelum ada peringkat

- Understanding EnvironmentDokumen3 halamanUnderstanding EnvironmentHeather TatBelum ada peringkat

- Understanding EnvironmentDokumen3 halamanUnderstanding EnvironmentabulzBelum ada peringkat

- Understanding EnvironmentDokumen3 halamanUnderstanding EnvironmentCharlyn C. Dela CruzBelum ada peringkat

- Eed Study GuideDokumen49 halamanEed Study Guidemmabatho nthutangcaroliBelum ada peringkat

- Eco-Lit FinalDokumen31 halamanEco-Lit FinalLoida Manongsong100% (1)

- "Greening of Education" - Ecological EducationDokumen2 halaman"Greening of Education" - Ecological EducationgotcanBelum ada peringkat

- Understanding EnvironmentDokumen3 halamanUnderstanding EnvironmentLucijaRomićBelum ada peringkat

- Sustainability Education Literature Review: Alessio SurianDokumen10 halamanSustainability Education Literature Review: Alessio SurianasurianBelum ada peringkat

- Ecological Literacy - Basic For A Sustainable FutureDokumen10 halamanEcological Literacy - Basic For A Sustainable Futureriddock100% (1)

- Protecting the Future: Stories of Sustainability from RMIT UniversityDari EverandProtecting the Future: Stories of Sustainability from RMIT UniversitySarah S. HoldsworthBelum ada peringkat

- 02 SynopsisDokumen20 halaman02 SynopsisRain JeideBelum ada peringkat

- Module 6Dokumen11 halamanModule 6Sugar Rey Rumart RemotigueBelum ada peringkat

- Bradbery 2013Dokumen18 halamanBradbery 2013Oscar Santiago VélezBelum ada peringkat

- Jaboneta - Ped8 - Eac LiteracyDokumen7 halamanJaboneta - Ped8 - Eac LiteracyJOANA BELEN CA�ETE JABONETABelum ada peringkat

- Module 6 Ecological LiteracyDokumen6 halamanModule 6 Ecological LiteracyCherry May ArrojadoBelum ada peringkat

- Concepts Module 6 Ecological LiteracyDokumen5 halamanConcepts Module 6 Ecological LiteracyAnn AzarconBelum ada peringkat

- Ecoliteracy EssayDokumen3 halamanEcoliteracy EssaySofi PeraltaBelum ada peringkat

- EnvironmentalDokumen88 halamanEnvironmentalJaya ChandranBelum ada peringkat

- Ecological Literacy Concept Digest: Literacy Was First Introduced by David Orr in 1989 in His EssayDokumen4 halamanEcological Literacy Concept Digest: Literacy Was First Introduced by David Orr in 1989 in His EssayJustin MagnanaoBelum ada peringkat

- Environment Systems and Decisions Volume 22 Issue 4 2002 (Doi 10.1023 - A - 1020766914456) M. Kassas - Environmental Education - Biodiversity PDFDokumen7 halamanEnvironment Systems and Decisions Volume 22 Issue 4 2002 (Doi 10.1023 - A - 1020766914456) M. Kassas - Environmental Education - Biodiversity PDFSyafranBelum ada peringkat

- Module 10: ECOLITERACY: Learning OutcomesDokumen10 halamanModule 10: ECOLITERACY: Learning OutcomesFaye Edmalyn De RojoBelum ada peringkat

- Global Environmental EthicsDokumen12 halamanGlobal Environmental EthicsJessica Jasmine MajestadBelum ada peringkat

- Biological Conservation: Heidi L. Ballard, Colin G.H. Dixon, Emily M. HarrisDokumen11 halamanBiological Conservation: Heidi L. Ballard, Colin G.H. Dixon, Emily M. HarrisAndrés Espinoza CaraBelum ada peringkat

- Environmental LiteracyDokumen14 halamanEnvironmental LiteracyMiguel Andre GarmaBelum ada peringkat

- Education for Sustainable Development in the Caribbean: Pedagogy, Processes and PracticesDari EverandEducation for Sustainable Development in the Caribbean: Pedagogy, Processes and PracticesBelum ada peringkat

- Social Science and SustainabilityDari EverandSocial Science and SustainabilityHeinz SchandlBelum ada peringkat

- ConnectDokumen24 halamanConnectLucìa SolerBelum ada peringkat

- Eda 3046 Latest MemoDokumen10 halamanEda 3046 Latest MemoJanine Toffar100% (5)

- Emp 410, Environmental EducationDokumen51 halamanEmp 410, Environmental EducationBrown BarakaBelum ada peringkat

- Eco LiteracyDokumen4 halamanEco LiteracyJoshua Quimson100% (2)

- Topic 7 EcoliteracyDokumen18 halamanTopic 7 EcoliteracyJovie VistaBelum ada peringkat

- Learning and Sustainability in Dangerous Times: The Stephen Sterling ReaderDari EverandLearning and Sustainability in Dangerous Times: The Stephen Sterling ReaderBelum ada peringkat

- DasdasdasdasdwwDokumen2 halamanDasdasdasdasdwwchitorelidze lukaBelum ada peringkat

- Culture of SustainabilityDokumen55 halamanCulture of SustainabilityRicardo Ernesto Pérez IbarraBelum ada peringkat

- Landscape and AcademicsDokumen15 halamanLandscape and AcademicsKola LawalBelum ada peringkat

- Chapter 1 - Introduction To Environmental EducationDokumen5 halamanChapter 1 - Introduction To Environmental EducationDarkness PlaysBelum ada peringkat

- Paper 7 - Environmental Ethics and Integrating Sustainability Into Management EducationDokumen15 halamanPaper 7 - Environmental Ethics and Integrating Sustainability Into Management EducationAshraf ImamBelum ada peringkat

- J Res Sci Teach - 2015 - Adler - The Effect of Explicit Environmentally Oriented Metacognitive Guidance and PeerDokumen44 halamanJ Res Sci Teach - 2015 - Adler - The Effect of Explicit Environmentally Oriented Metacognitive Guidance and PeerSiti Nazirah ButaiBelum ada peringkat

- Chapter 10 - Eco LiteracyDokumen15 halamanChapter 10 - Eco LiteracyMichelle Bandoquillo100% (1)

- Environmental Education April 4 2012Dokumen8 halamanEnvironmental Education April 4 2012Rodger JonesBelum ada peringkat

- CoCreation CRFDokumen10 halamanCoCreation CRFDean SaittaBelum ada peringkat

- hs2023 Cheung Zi Qing Glenda Tutorial Group 3 MidtermDokumen6 halamanhs2023 Cheung Zi Qing Glenda Tutorial Group 3 Midtermapi-548764406Belum ada peringkat

- Ecological Literacy in Design EducationDokumen11 halamanEcological Literacy in Design EducationKillian RodriguezBelum ada peringkat

- Env 2Dokumen13 halamanEnv 2MUSHIMIYIMANA InnocentBelum ada peringkat

- Eda 3046 Exam MemoDokumen11 halamanEda 3046 Exam MemoJanine Toffar92% (39)

- Education For Sustainable Development ReportDokumen25 halamanEducation For Sustainable Development ReportTheresa Lopez VelascoBelum ada peringkat

- Williamsiemer PaperDokumen19 halamanWilliamsiemer PaperYung Siok YiiBelum ada peringkat

- Thesis On Environmental EducationDokumen4 halamanThesis On Environmental Educationlarissaswensonsiouxfalls100% (2)

- Ethics and Sustainability: Center For Humans & NatureDokumen3 halamanEthics and Sustainability: Center For Humans & NatureTarun KeimBelum ada peringkat

- Cookbook PDFDokumen38 halamanCookbook PDFfrancoisedonzeau1310Belum ada peringkat

- Pi (3.14) Day (3/14) and Einstein's Birthday: Where Have You Seen ?Dokumen8 halamanPi (3.14) Day (3/14) and Einstein's Birthday: Where Have You Seen ?francoisedonzeau1310Belum ada peringkat

- T H e P e R I o D I C T A B L e o F T H e E L e M e N T SDokumen24 halamanT H e P e R I o D I C T A B L e o F T H e E L e M e N T Sfrancoisedonzeau1310Belum ada peringkat

- Dear Families:: Grades 7-8 Gifted 6 Family Activity PagesDokumen4 halamanDear Families:: Grades 7-8 Gifted 6 Family Activity Pagesfrancoisedonzeau1310Belum ada peringkat

- Pi Day Pie Problems FreebieDokumen5 halamanPi Day Pie Problems Freebiefrancoisedonzeau1310Belum ada peringkat

- Math Mosaics: A Fun Math Activity Brought To You by Pamela MoeaiDokumen3 halamanMath Mosaics: A Fun Math Activity Brought To You by Pamela Moeaifrancoisedonzeau1310Belum ada peringkat

- Factor ThisDokumen1 halamanFactor Thisfrancoisedonzeau1310Belum ada peringkat

- Matching Game - PaintingsDokumen1 halamanMatching Game - Paintingsfrancoisedonzeau1310Belum ada peringkat

- Math Study Tips You Wont ForgetDokumen4 halamanMath Study Tips You Wont Forgetfrancoisedonzeau1310Belum ada peringkat

- Maths Four Operations Vocabulary PosterDokumen1 halamanMaths Four Operations Vocabulary Posterfrancoisedonzeau1310Belum ada peringkat

- Latitude Circles Interactive Lines WNDokumen3 halamanLatitude Circles Interactive Lines WNfrancoisedonzeau1310Belum ada peringkat

- Ocean Zones WNDokumen3 halamanOcean Zones WNfrancoisedonzeau1310Belum ada peringkat

- Written Information From HTTP://WWW - Collectionscanada.gc - Ca/ Maps From Ational GeographicDokumen4 halamanWritten Information From HTTP://WWW - Collectionscanada.gc - Ca/ Maps From Ational Geographicfrancoisedonzeau1310Belum ada peringkat

- Math Laws Self-Check WorksheetDokumen3 halamanMath Laws Self-Check Worksheetfrancoisedonzeau1310Belum ada peringkat

- Retail Strategy: MarketingDokumen14 halamanRetail Strategy: MarketingANVESHI SHARMABelum ada peringkat

- Romeo and Juliet: Unit Test Study GuideDokumen8 halamanRomeo and Juliet: Unit Test Study GuideKate Ramey100% (7)

- Gouri MohammadDokumen3 halamanGouri MohammadMizana KabeerBelum ada peringkat

- XZNMDokumen26 halamanXZNMKinza ZebBelum ada peringkat

- Suffolk County Substance Abuse ProgramsDokumen44 halamanSuffolk County Substance Abuse ProgramsGrant ParpanBelum ada peringkat

- Ethical Dilemma Notes KiitDokumen4 halamanEthical Dilemma Notes KiitAritra MahatoBelum ada peringkat

- Joseph Minh Van Phase in Teaching Plan Spring 2021Dokumen3 halamanJoseph Minh Van Phase in Teaching Plan Spring 2021api-540705173Belum ada peringkat

- Public Provident Fund Card Ijariie17073Dokumen5 halamanPublic Provident Fund Card Ijariie17073JISHAN ALAMBelum ada peringkat

- Tugas Etik Koas BaruDokumen125 halamanTugas Etik Koas Baruriska suandiwiBelum ada peringkat

- BB 100 - Design For Fire Safety in SchoolsDokumen160 halamanBB 100 - Design For Fire Safety in SchoolsmyscriblkBelum ada peringkat

- Actividad N°11 Ingles 4° Ii Bim.Dokumen4 halamanActividad N°11 Ingles 4° Ii Bim.jamesBelum ada peringkat

- Design and Pricing of Deposit ServicesDokumen37 halamanDesign and Pricing of Deposit ServicesThe Cultural CommitteeBelum ada peringkat

- Knitting TimelineDokumen22 halamanKnitting TimelineDamon Salvatore100% (1)

- Problem Solving and Decision MakingDokumen14 halamanProblem Solving and Decision Makingabhiscribd5103Belum ada peringkat

- People vs. PinlacDokumen7 halamanPeople vs. PinlacGeenea VidalBelum ada peringkat

- Account Number:: Rate: Date Prepared: RS-Residential ServiceDokumen4 halamanAccount Number:: Rate: Date Prepared: RS-Residential ServiceAhsan ShabirBelum ada peringkat

- WHO in The Philippines-Brochure-EngDokumen12 halamanWHO in The Philippines-Brochure-EnghBelum ada peringkat

- Mandatory Minimum Requirements For Security-Related Training and Instruction For All SeafarersDokumen9 halamanMandatory Minimum Requirements For Security-Related Training and Instruction For All SeafarersDio Romero FariaBelum ada peringkat

- ZodiacDokumen6 halamanZodiacapi-26172340Belum ada peringkat

- Taking The Red Pill - The Real MatrixDokumen26 halamanTaking The Red Pill - The Real MatrixRod BullardBelum ada peringkat

- Running Wild Lyrics: Album: "Demo" (1981)Dokumen6 halamanRunning Wild Lyrics: Album: "Demo" (1981)Czink TiberiuBelum ada peringkat

- Breterg RSGR: Prohibition Against CarnalityDokumen5 halamanBreterg RSGR: Prohibition Against CarnalityemasokBelum ada peringkat

- Digest Pre TrialDokumen2 halamanDigest Pre TrialJei Essa AlmiasBelum ada peringkat

- SPED-Q1-LWD Learning-Package-4-CHILD-GSB-2Dokumen19 halamanSPED-Q1-LWD Learning-Package-4-CHILD-GSB-2Maria Ligaya SocoBelum ada peringkat

- Inversion in Conditional SentencesDokumen2 halamanInversion in Conditional SentencesAgnieszka M. ZłotkowskaBelum ada peringkat

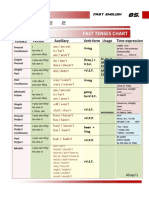

- Table 2: Fast Tenses ChartDokumen5 halamanTable 2: Fast Tenses ChartAngel Julian HernandezBelum ada peringkat

- Southwest CaseDokumen13 halamanSouthwest CaseBhuvnesh PrakashBelum ada peringkat

- Warhammer Armies: The Army of The NorseDokumen39 halamanWarhammer Armies: The Army of The NorseAndy Kirkwood100% (2)

- Options TraderDokumen2 halamanOptions TraderSoumava PaulBelum ada peringkat

- Profil AVANCER FM SERVICES SDN BHDDokumen23 halamanProfil AVANCER FM SERVICES SDN BHDmazhar74Belum ada peringkat