Ellington, Duke in Oxford Music Online

Diunggah oleh

Marcio GarciaHak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Ellington, Duke in Oxford Music Online

Diunggah oleh

Marcio GarciaHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Ellington, Duke in Oxford Music Online

http://0-www.oxfordmusiconline.com.bianca.penlib.du.edu/subscriber/...

Oxford Music Online

1 of 7

5/23/13 4:26 PM

Ellington, Duke in Oxford Music Online

http://0-www.oxfordmusiconline.com.bianca.penlib.du.edu/subscriber/...

Grove Music Online Ellington, Duke

article url: http://0-www.oxfordmusiconline.com.bianca.penlib.du.edu/subscriber/article/grove/music/08731

Ellington, Duke [Edward Kennedy]

(b Washington, DC, 29 April 1899; d New York, 24 May 1974). American jazz composer, bandleader and pianist. He was for decades a leading figure in big-band jazz and remains the most significant composer of the genre.

1. Life.

Ellingtons father was a butler and intended him to become an artist. He began to study the piano when he was seven and was much influenced by the ragtime pianists; at the age of 17 he made his professional debut. His first visit to New York, in early 1923, ended in financial failure, but on Fats Wallers advice he moved there later that year with Elmer Snowdens Washington band, the Washingtonians: Sonny Greer (drums), Otto Hardwick (saxophones), Snowden (banjo) and Artie Whetsol (trumpet). Between 1923 and 1927 this small group, which played at the Hollywood and Kentucky clubs on Broadway, was gradually enlarged to a ten-piece orchestra by the addition of Bubber Miley (trumpet), Tricky Sam Nanton (trombone), Harry Carney (baritone saxophone), Rudy Jackson (clarinet and tenor saxophone) and Wellman Braud (double bass); Fred Guy replaced Snowden on banjo. The bands early recordings (East St Louis Toodle-oo, 1926, Vic., and Black and Tan Fantasy, 1927, Bruns.) reveal growing originality. During the following period (192730), at the Cotton Club in Harlem, Ellington began to share with Louis Armstrong the leading position in the jazz world. The orchestra grew to 12 musicians, including Barney Bigard (clarinet), Johnny Hodges (saxophone) and Cootie Williams (trumpet). The group went to Hollywood to appear in the film Check and Double Check (1930) and in New York made about 200 recordings, many in the jungle style that was one of Ellingtons and Mileys most individual creations. The success of Mood Indigo (1930, Vic.) brought Ellington worldwide fame, and in 1931 he began experiments in extended composition with Creole Rhapsody (Bruns.), later to be followed by Reminiscing in Tempo (1935, Bruns.) and Diminuendo and Crescendo in Blue (1937, Bruns.). The decade from 1932 to 1942 was Ellingtons most creative. His band, consisting now of six brass instruments, four reeds and a four-man rhythm section, performed in many American cities and made highly successful concert tours of Europe in 1933 and 1939. In 193940 there were more important additions to the band: Jimmy Blanton (double bass), Ben Webster (tenor saxophone) and most notably Billy Strayhorn, as arranger, composer and second pianist. At this time Ellington created several outstanding short works, in particular Concerto for Cootie, Ko-Ko and Cotton Tail (all 1940, Vic.). In the mid-1940s the orchestra was enlarged again: by 1946 it included 18 players. But the previous stability of personnel declined and Ellingtons writing, based on his members individual styles, began to suffer from the constant changes. Some excellent soloists, however, were added: Ray Nance (trumpet and violin), Shorty Baker (trumpet) and Jimmy Hamilton (clarinet). In January 1943 Ellington inaugurated a series of annual concerts at Carnegie Hall with his monumental work Black, Brown and Beige, a tone parallel originally conceived in five sections and intended to portray the history of the black people in the USA through their music. Other ambitious works followed. After Ellington abandoned these concerts in 1952, the development of the long-playing record allowed him to create other multi-movement suites. From 1950 Ellington continued to expand the scope of his compositions and his activities as a bandleader [not available online]. His foreign tours became increasingly About the Index frequent and successful

Show related links Search across all sources

2 of 7

5/23/13 4:26 PM

Ellington, Duke in Oxford Music Online

http://0-www.oxfordmusiconline.com.bianca.penlib.du.edu/subscriber/...

composed his first full-length film score, for Otto Premingers Anatomy of a Murder(1959), and his first incidental music, for Alain Ren Le Sages Turcaret (1960). He also made recordings with younger jazz musicians such as John Coltrane, Charles Mingus and Max Roach (Money Jungle, 1962, UA). In his last decade Ellington wrote mostly liturgical music: In the Beginning God (for a standard jazz orchestra, narrator, chorus, two soloists and dancer) was performed in Grace Cathedral, San Francisco (1965), and this was followed by other sacred services. Among his numerous awards and honours were doctorates from Howard University (1963) and Yale University (1967) and the Presidential Medal of Honor (1969); in 1970 he was made a member of the National Institute of Arts and Letters, and in 1971 he became the first jazz musician to be named a member of the Swedish Royal Academy of Music in Stockholm. A documentary film of Ellington and his orchestra, On the Road with Duke Ellington, was made in 1974. Ellington directed his band until his death, when it was taken over by his son Mercer Ellington.

2. Style and musical language.

Ellington taught himself harmony at the piano and acquired the rudiments of orchestration by experimenting with his band; his orchestra was a workshop in which he consulted his players and tried out alternative solutions. During the formative Cotton Club period Ellington was obliged to work in a variety of musical categories: numbers for dancing, jungle-style and production numbers, popular songs, blue or mood pieces, as well as pure instrumental jazz compositions. During this period, too, Ellington developed an extraordinary symbiotic relationship with his orchestra it was his instrument even more than the piano enabling him to experiment with the timbral colourings, tonal effects and unusual voicings that became the hallmark of his style; the Ellington effect (Strayhorns term) was virtually inimitable because it depended in large part on the particular timbre and style of each player. Remarkably, though no two players in Ellingtons orchestra sounded alike, they could, when called upon, produce the most ravishing blends and ensembles of sonority known to jazz. An outstanding early example of the Ellington effect may be heard on Mood Indigo (1930), in which the traditional roles of the three front-line instruments in New Orleans collective improvisation clarinet (high-register obbligato), trumpet (melody or theme) and trombone (bass or tenor counterthemes) are inverted so that the muted trumpet plays on top; the plunger-muted trombone functions as a high-register second voice, and the clarinet sounds more than an octave below in its chalumeau register. In the early and mid-1920s orchestral jazz arrangements were rudimentary, serving only the simplest functions of dance music. But Ellington (along with Don Redman, Fletcher Henderson and John Nesbitt) developed an elaborate, diversified concept of arranging, which incorporated the essence of the current hot style of solo improvisation. In this he was greatly aided and influenced by the extraordinary expressive and technical capabilities of his two principal brass players, Bubber Miley and Tricky Sam Nanton, who were both experts of the so-called growl and plunger style. These often pungent sonorities, when blended or juxtaposed with the smoother sounds of the saxophone, provided Ellington with an orchestral palette more colourful and varied than that of any other orchestra of the time (with the possible exception of Paul Whitemans). Faced with the formal problem posed by jazz arrangement how best to integrate solo improvisation Ellington learnt to exploit expertly the contrast produced by the soloists entry, so as to project him into the musics movement and entrust him with its development. This partly explains why even Ellingtons finest soloists seemed lustreless after leaving his orchestra. He also had a singular gift for devising orchestral accompaniments for improvisation; no arrangers, except perhaps Sy Oliver and Gil Evans, have imagined instrumental combinations as beautiful as those of Mystery Song (1931, Vic.), Saddest Tale (1934, Bruns.), Delta Serenade (1934, Vic.), Azure (1937, Master), Subtle Lament (1939, Bruns.), Dusk (1940, Vic.), Ko-Ko (1940, Vic) and Moon Mist (1942, Vic.).

About the Index Show related links Search across all sources

3 of 7

5/23/13 4:26 PM

Ellington, Duke in Oxford Music Online

http://0-www.oxfordmusiconline.com.bianca.penlib.du.edu/subscriber/...

himself as a soloist with his orchestra, he was nevertheless a remarkably individual contributor to the overall Ellington effect. He saw himself primarily as a catalyst and an accompanist, a feeder of ideas and rhythmic energy to the band as a whole or to its soloists. In this unobtrusive role, playing only when necessary, he was known for remaining silent during entire choruses or indeed pieces. His piano tone, produced deep in the keys, was the richest and most resonant imaginable; it had the ability to energize and inspire the entire orchestra. Although he was an erratic soloist in his early years and sometimes relied on pianistic clichs incessant downward-fluttering arpeggios, for instance Ellington could on occasion vie with the best players. An outstanding example of his work as a pianist-composer is Clothed Woman (1947, Col.), remarkable for its virtually complete atonality (ex.1). He also wrote a Piano Method for Blues (New York, 1943).

Ex.1 Introduction to Clothed Woman (1947, Col.); transcr. G. Schuller

3. Compositions.

Ellington is generally recognized as the most important composer in jazz history. Most of the enormous number of works he recorded are his own; the exact number of his compositions is unknown, but is estimated at about 2000, including hundreds of three-minute instrumental pieces (for 78 r.p.m. recordings), popular songs (many consisting of instrumental pieces to which lyrics by Irving Mills and others were added), large-scale suites, several musical comedies, many film scores and an incomplete and unperformed opera, Boola. Ellington combined a flair for orchestration with extraordinary gifts as a bandleader; while other jazz composers had comparable talent, they lacked the organizational abilities necessary to create and maintain a permanent orchestral vehicle. The excerpt from Ko-Ko (ex.2), showing the orchestration of a passage from an ensemble section, is one of the most remarkable pieces in all of Ellingtons writing.

Ex.2 From Ko-Ko (1940, Vic.); transcr. G. Schuller (all parts notated at sounding pitch) Courtesy of Gunther Schuller

Ellington was one of the first musicians to concern himself with composition and musical form in jazz as distinct from improvisation, tune writing and arranging. In Concerto for Cootie, ten-bar phrases are combined into a complex ternary form which abandons the chorus structure common to most jazz. In Cotton Tail, from the same period, Ellington made use of a call-and-response technique of writing in order to heighten the drama of the last climactic chorus (ex.3). Black, Brown and Beige uses symphonic devices (the fragmentation and development of motifs, thematic recall and mottoes) as well as symphonic proportions in its several sections; it is thus perhaps unique among Ellingtons earlier works, showing a preoccupation with form far in advance of his contemporaries. Only a few jazz musicians (among them Thelonious Monk, Charles Mingus and Gil Evans) have followed Ellington in this respect.

About the Index Show related links Search across all sources

4 of 7

5/23/13 4:26 PM

Ellington, Duke in Oxford Music Online

http://0-www.oxfordmusiconline.com.bianca.penlib.du.edu/subscriber/...

Ex.3 From the fifth chorus of Cotton Tail (1940, Vic.); transcr. G. Schuller (all parts notated at sounding pitch) Courtesy of Gunther Schuller

Ellingtons prodigious productivity makes an overview of his work virtually impossible. But it is generally agreed that he attained the zenith of his creativity in the late 1930s and early 1940s, and that he worked best in the miniature forms dictated by the three-minute ten-inch disc. His creativity declined somewhat after the 1940s, many of the late-period extended compositions and multimovement suites generally suffering, despite their occasional visionary inspirations, from a diminished, less consistent originality and hasty work, mostly occasioned by incessant touring. But even lesser Ellington is bound to be of above-average quality, and the work in recent years of Wynton Marsalis and his Lincoln Centre Jazz Orchestras championing of Ellingtons late work has led to a more favourable assessment in many quarters. Serious study of Ellingtons oeuvre has also been hampered by an almost total absence to date of his scores in published form, having thus to rely on transcriptions from recordings. However, in recent years the newly acquired holdings of several hundred thousand sheets of Ellingtons scores and parts at the Smithsonian Institute has at last provided easier access to the immensity of Ellingtons oeuvre.

Bibliography

Search RILM

Discographies and film guides

L. Massagli, L. Pusateri and G.M. Volont: Duke Ellingtons Story on Records (Milan, 196683) W.E. Timner: Ellingtonia: the Recorded Music of Duke Ellington and his Sidemen (Metuchen, NJ, 3/1988)

O.J. Nielsen: Jazz Records, 194280: a Discography, vi, ed. E. Rabin (Copenhagen, 1989) K. Stratemann: Duke Ellington: Day by Day and Film by Film (Copenhagen, c1992) J. Valburn: Duke Ellington on Compact Disc (Hicksville, NY, 1993)

Biographies

D. Preston: Mood Indigo (Egham, 1946) J. de Trazegnies: Duke Ellington: Harlem Aristocrat of Jazz (Brussels, 1946) B. Ulanov: Duke Ellington (New York, 1946/R) P. Gammond, ed.: Duke Ellington: his Life and Music (London, 1958/R) G.E. Lambert: Duke Ellington (London, 1959); repr. in Kings of Jazz, ed. S. Green (South Brunswick, NJ, About the Index Show related links Search across all sources

5 of 7

5/23/13 4:26 PM

Ellington, Duke in Oxford Music Online

http://0-www.oxfordmusiconline.com.bianca.penlib.du.edu/subscriber/...

S. Dance: The World of Duke Ellington (London, 1970/R) [collection of previously pubd articles and interviews] D. Ellington: Music is my Mistress (Garden City, NY, 1973; index by H.F. Huon pubd separately, Melbourne, c1977, 2/1982) D. Jewell: Duke: a Portrait of Duke Ellington (London, 1977, 2/1978) S. Dance and D. Morgenstern: disc notes, Giants of Jazz: Duke Ellington, TL J02 (1978) M. Ellington and S. Dance: Duke Ellington in Person: an Intimate Memoir (Boston, 1978) D. George: The Real Duke Ellington (London, 1982) H. Ruland: Duke Ellington: sein Leben, seine Musik, seine Schallplatten (Gauting, 1983) P. Gammond: Duke Ellington (London, 1987) [incl. discography] J.L. Collier: Duke Ellington (New York, 1987)

General studies and essays

R.D. Darrell: Black Beauty, Disques [Philadelphia], iii/4 (19323), 15261 R. de Toledano: Frontiers of Jazz (New York, 1947, 2/1962) V. Bellerby: Duke Ellington, JazzM, i (1955), no.9, pp.267; no.l0, pp.2830; i/12 (1956), 911, 31; ii/2 (1956), 2830 N. Shapiro and N. Hentoff, eds.: The Jazz Makers: Essays of the Greats of Jazz (New York, 1957/R)

W. Balliett: Ecstasy at the Onion (New York, 1971) [collection of previously pubd articles and reviews]

L. Feather: From Satchmo to Miles (New York, 1972) R. Stewart: Jazz Masters of the Thirties (New York, c1972) A. McCarthy: Big Band Jazz (New York, 1974/R) R.J. Gleason: Celebrating the Duke: and Louis, Bessie, Billie, Bird, Carmen, Miles, Dizzy and other Heroes (Boston, 1975), 153266 [incl. A Ducal Calendar 19521974, 169262] M. Tucker, ed.: The Duke Ellington Reader (New York, 1993)

Musical analyses

A. Hodier: Hommes et problmes du jazz, suivi de La religion du jazz (Paris, 1954; Eng. trans., rev. 1956/R, 2/1979, as Jazz: its Evolution and Essence) M. Clar: The Style of Duke Ellington, JR, ii/3 (1959), 610 About the Index Show related links Search across all sources

6 of 7

5/23/13 4:26 PM

Ellington, Duke in Oxford Music Online

http://0-www.oxfordmusiconline.com.bianca.penlib.du.edu/subscriber/...

M. Harrison: The Anatomy of a Murder Music, JR, ii/10 (1959), 356 M. Harrison: Ellingtons Back to Back, JR, iii/3 (1960), 245 A.J. Bishop: Dukes Creole Rhapsody, JazzM, ix/9 (19634), 1213 M. Harrison: Duke Ellington: Reflections on Some of the Larger Works, JazzM, ix/11 (19634), 1215

A. Bishop: Reminiscing in Tempo: an Analysis, JJ, xvii/2 (1964), 56 W. Mellers: Music in a New Found Land: Themes and Developments in the History of American Music (London, 1964/R) W.W. Austin: Music in the 20th Century: from Debussy through Stravinsky (New York, 1966) G. Schuller: The Ellington Style: its Origins and Early Development, Early Jazz: its Roots and Musical Development (New York, 1968/R), 31857 E. Lambert: Duke Ellington on Reprise, JJ, xxii/5 (1969), 24 E. Lambert: Quality Jazz, no.l4: Duke Ellingtons Nutcracker Suite, JJ, xxii/11 (1969), 11 only B. Priestley: Duke Ellingtons Greatest Recordings and the Far East Suite, JazzM, xv/1 (1969), 1719

A.J. Bishop: The Protean Imagination of Duke Ellington: the Early Years, JJ, xxiv (1971), no.10, pp.24; no.12, pp.1214 M. Elliott: Duke and the Blues, JJ, xxvii/11 (1974), 1819 B. Priestley and A. Cohen: Black, Brown and Beige, Composer, no.51 (1974), 337; no.52 (1974), 2932; no.53 (19745), 2932 C. Sheridan: Piano in the Background, Into Jazz, i/6 (1974), 6 G. Schuller: Musings (New York, 1986), 4759 G. Schuller: Duke Ellington: Master Composer, The Swing Era: the Development of Jazz, 19301945 (New York, 1989), 46157

Oral history material in US-NH; recordings and other material in US-DN; collection of scores in George P. Vanier Library of Cancordia University, Montreal

Andr Hodeir/Gunther Schuller

Copyright Oxford University Press 2007 2013.

About the Index Show related links Search across all sources

7 of 7

5/23/13 4:26 PM

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- Ahmad Jamal-The CollectionDokumen109 halamanAhmad Jamal-The CollectionBrad Hendershot100% (3)

- Keep Forgettin Michael Macdonald PDFDokumen1 halamanKeep Forgettin Michael Macdonald PDFMarcio GarciaBelum ada peringkat

- African Music ppt1Dokumen117 halamanAfrican Music ppt1Paulo Renz CastroBelum ada peringkat

- Romeo & Juliet TimelineDokumen6 halamanRomeo & Juliet TimelineblistboyBelum ada peringkat

- The Genesis of BlackBrownandBeigeDokumen20 halamanThe Genesis of BlackBrownandBeigealeketenBelum ada peringkat

- Odd Couple Dramaturgy PacketDokumen20 halamanOdd Couple Dramaturgy PacketTheater J50% (2)

- Clare Fischer - Composer, Arranger, Pianist, Recording ArtistDokumen2 halamanClare Fischer - Composer, Arranger, Pianist, Recording ArtistbennyBelum ada peringkat

- Study Guide - Flat StanleyDokumen12 halamanStudy Guide - Flat StanleymontalvoartsBelum ada peringkat

- From Now On: From "The Greatest Showman"Dokumen7 halamanFrom Now On: From "The Greatest Showman"jerrychen25Belum ada peringkat

- Melodic ParaphraseDokumen9 halamanMelodic ParaphraseMarcio Garcia67% (3)

- Sunny MurrayDokumen14 halamanSunny MurraylushimaBelum ada peringkat

- Du TranscriptDokumen5 halamanDu TranscriptMarcio GarciaBelum ada peringkat

- 4 History of American MusicDokumen416 halaman4 History of American MusicglassyglassBelum ada peringkat

- Moontrane PDFDokumen2 halamanMoontrane PDFMarcio GarciaBelum ada peringkat

- The History and Development of Jazz Piano - A New Perspective For PDFDokumen264 halamanThe History and Development of Jazz Piano - A New Perspective For PDFburgundio100% (1)

- Listening For HistoryDokumen7 halamanListening For HistoryVincenzo MartorellaBelum ada peringkat

- The Music and Musical Instruments of Japan.Dokumen296 halamanThe Music and Musical Instruments of Japan.Maria FernandaBelum ada peringkat

- A New Orleans Jazz-HistoryDokumen16 halamanA New Orleans Jazz-HistoryyagmursenaaaaBelum ada peringkat

- Hip Hop in History: Past, Present, and FutureDokumen7 halamanHip Hop in History: Past, Present, and FuturesusantothBelum ada peringkat

- GlazunovDokumen4 halamanGlazunovLionel J. LewisBelum ada peringkat

- JazzDokumen35 halamanJazzPaco Luis GarciaBelum ada peringkat

- The Contemporary Hollywood Film Soundtrack - Professional Practies and Sonic Styles Since The 1970sDokumen337 halamanThe Contemporary Hollywood Film Soundtrack - Professional Practies and Sonic Styles Since The 1970sAnonymous o9GBGXBelum ada peringkat

- Nettl Study of EthnomusicologyDokumen6 halamanNettl Study of EthnomusicologyJaden SumakudBelum ada peringkat

- Ellingtonia - MilnerDokumen226 halamanEllingtonia - MilnerGabriel de OliveiraBelum ada peringkat

- Chris McGregor: South African Jazz PioneerDokumen19 halamanChris McGregor: South African Jazz PioneerJoshua Paula E SilvaBelum ada peringkat

- Joseph Jarman's Black Case Volume I & II explores exile and returnDokumen11 halamanJoseph Jarman's Black Case Volume I & II explores exile and returnGiannis KritsotakisBelum ada peringkat

- History of Classic Jazz (from its beginnings to Be-Bop)Dari EverandHistory of Classic Jazz (from its beginnings to Be-Bop)Belum ada peringkat

- Mal Waldron: American jazz pianist and composerDokumen5 halamanMal Waldron: American jazz pianist and composerburkeBelum ada peringkat

- Timeline (Up To 1929)Dokumen3 halamanTimeline (Up To 1929)JoseVeraBelloBelum ada peringkat

- PIGGOTT-Japanese Music PDFDokumen242 halamanPIGGOTT-Japanese Music PDFRenan VenturaBelum ada peringkat

- Jazz: Changing Racial BoundariesDokumen5 halamanJazz: Changing Racial Boundarieswwmmcf100% (1)

- Anatomy of A Woman: How Duke Ellington's Anatomy of A Murder Score Tells The Story of The Film's Female CharactersDokumen10 halamanAnatomy of A Woman: How Duke Ellington's Anatomy of A Murder Score Tells The Story of The Film's Female CharactersAndi CwiekaBelum ada peringkat

- Score Study English 2020Dokumen1 halamanScore Study English 2020MaxBelum ada peringkat

- Debussy's Use of American Minstrelsy Elements in His Piano WorksDokumen11 halamanDebussy's Use of American Minstrelsy Elements in His Piano WorksKatya KatyaBelum ada peringkat

- Composers As EthnographersDokumen256 halamanComposers As EthnographersDice MidyantiBelum ada peringkat

- Arhai's Serbian Ethno Music Reimagined for British MarketDokumen23 halamanArhai's Serbian Ethno Music Reimagined for British MarketJasmina MilojevicBelum ada peringkat

- What Was This Thing Called Jazz I o OsterhoffDokumen66 halamanWhat Was This Thing Called Jazz I o OsterhoffFernando Lameda GarcíaBelum ada peringkat

- Terry Riley Press Clips: April 17, 2009Dokumen5 halamanTerry Riley Press Clips: April 17, 2009larissa_slezak4570Belum ada peringkat

- VCFA Ellington Lecture Andy Jaffe Feb 2017Dokumen24 halamanVCFA Ellington Lecture Andy Jaffe Feb 2017Ignacio OrobitgBelum ada peringkat

- Othello - DesdemonaDokumen3 halamanOthello - DesdemonaSamuel WatkinsonBelum ada peringkat

- 20th Century Music - Jazz Post WarDokumen7 halaman20th Century Music - Jazz Post WarJoe TannerBelum ada peringkat

- Modernism and ImprovisationDokumen3 halamanModernism and ImprovisationGary Martin RolinsonBelum ada peringkat

- Goodbye To Berlin To Cabaret-Zeynep SehiraltiDokumen12 halamanGoodbye To Berlin To Cabaret-Zeynep SehiraltiZeynep SehiraltiBelum ada peringkat

- Chorus, Pre Chorus, Verse - Lyric StructureDokumen83 halamanChorus, Pre Chorus, Verse - Lyric StructureAlessandro S. CastroBelum ada peringkat

- Charles Mingus - Penguin Jazz 5thDokumen10 halamanCharles Mingus - Penguin Jazz 5thDiego RodriguezBelum ada peringkat

- Maurice Nicoll The Mark PDFDokumen4 halamanMaurice Nicoll The Mark PDFErwin KroonBelum ada peringkat

- Duke Ellington Research PaperDokumen13 halamanDuke Ellington Research Paperapi-310186257Belum ada peringkat

- Mawer, Deborah - Historical Overview, French Music and Jazz in ConversationDokumen27 halamanMawer, Deborah - Historical Overview, French Music and Jazz in ConversationKier ManimtimBelum ada peringkat

- Franck-Variations Symphoniques For Piano and OrchestraDokumen2 halamanFranck-Variations Symphoniques For Piano and OrchestraAlexandra MgzBelum ada peringkat

- ViolinDokumen22 halamanViolinIoan-ovidiu Cordis100% (1)

- The Directors Eye - OCRDokumen353 halamanThe Directors Eye - OCRA JBelum ada peringkat

- Auto-Biography Gerry Mulligan PDFDokumen84 halamanAuto-Biography Gerry Mulligan PDFDamián BirbrierBelum ada peringkat

- Miles Davis DiscographyDokumen122 halamanMiles Davis DiscographyAquí No HaynadieBelum ada peringkat

- Literature and Data CollectionDokumen17 halamanLiterature and Data CollectionShaili83% (6)

- I Remember: Eighty Years of Black Entertainment, Big Bands, and the BluesDari EverandI Remember: Eighty Years of Black Entertainment, Big Bands, and the BluesBelum ada peringkat

- Balkan Brass BattleDokumen2 halamanBalkan Brass BattleJoanaTristãoSilvaBelum ada peringkat

- Choreographic Music 0Dokumen555 halamanChoreographic Music 0Carlos GutiérrezBelum ada peringkat

- MonkDokumen8 halamanMonkapi-252001312Belum ada peringkat

- Jazz and The American IdentityDokumen3 halamanJazz and The American Identitybr3gz100% (1)

- Monk Bibliography of StudiesDokumen9 halamanMonk Bibliography of StudiesadelmobluesBelum ada peringkat

- History of Nigerian JazzDokumen55 halamanHistory of Nigerian JazzburgundioBelum ada peringkat

- A Conversation With: Jazz Pianist Vijay Iyer - The New York TimesDokumen5 halamanA Conversation With: Jazz Pianist Vijay Iyer - The New York TimesPietreSonoreBelum ada peringkat

- Charles Mingus Jazz Workshop Concerts 1964-65Dokumen3 halamanCharles Mingus Jazz Workshop Concerts 1964-65stringbender12Belum ada peringkat

- Recording Jazz Problems EssayDokumen7 halamanRecording Jazz Problems Essaymusicessays100% (1)

- RABIH ABOU-KHALIL DiscographyDokumen3 halamanRABIH ABOU-KHALIL DiscographyDamion HaleBelum ada peringkat

- The Sextet of Orchestra - Mack The KnifeDokumen3 halamanThe Sextet of Orchestra - Mack The KnifeGagrigoreBelum ada peringkat

- Mu 018014Dokumen54 halamanMu 018014Eduardo MontielBelum ada peringkat

- Glossary of Musical TermsDokumen18 halamanGlossary of Musical TermsJason TiongcoBelum ada peringkat

- Charlie Christian - ReferenceDokumen6 halamanCharlie Christian - Referencejoao famaBelum ada peringkat

- Richard Crawford On Gershwin's PorgyDokumen4 halamanRichard Crawford On Gershwin's PorgyJoseph100% (1)

- PhilipDokumen23 halamanPhilipJV YbañezBelum ada peringkat

- Articles Jazz and The New Negro: Harlem'S Intellectuals Wrestle With The Art of The AgeDokumen18 halamanArticles Jazz and The New Negro: Harlem'S Intellectuals Wrestle With The Art of The AgeEdson IkêBelum ada peringkat

- Date Developments in Jazz Historical EventsDokumen7 halamanDate Developments in Jazz Historical EventsJoseVeraBelloBelum ada peringkat

- The Complete Arista Recordings of Anthony Braxton (#242)Dokumen6 halamanThe Complete Arista Recordings of Anthony Braxton (#242)David A. LangnerBelum ada peringkat

- Music and Musicians of The Mississippi RiverbboatsDokumen28 halamanMusic and Musicians of The Mississippi RiverbboatsJohn DePaolaBelum ada peringkat

- Taylor Eigsti - Quotes: Music OnDokumen1 halamanTaylor Eigsti - Quotes: Music OnMarcio GarciaBelum ada peringkat

- Drop Dead LeadsheetDokumen3 halamanDrop Dead LeadsheetMarcio GarciaBelum ada peringkat

- Front Page Village Vanguard PDFDokumen1 halamanFront Page Village Vanguard PDFMarcio GarciaBelum ada peringkat

- Translated Listin ArticleDokumen2 halamanTranslated Listin ArticleMarcio GarciaBelum ada peringkat

- As Cap Label PrintDokumen1 halamanAs Cap Label PrintMarcio GarciaBelum ada peringkat

- All About JazzrDokumen1 halamanAll About JazzrMarcio GarciaBelum ada peringkat

- Marcio Garcia BioDokumen1 halamanMarcio Garcia BioMarcio GarciaBelum ada peringkat

- All About JazzrDokumen1 halamanAll About JazzrMarcio GarciaBelum ada peringkat

- 2311476-Star Wars Theme - Easy Piano PDFDokumen1 halaman2311476-Star Wars Theme - Easy Piano PDFChiriko ChiBelum ada peringkat

- Teacher Letter DraftDokumen1 halamanTeacher Letter DraftMarcio GarciaBelum ada peringkat

- Music Poster Image from Musicaneo WebsiteDokumen1 halamanMusic Poster Image from Musicaneo WebsiteMarcio GarciaBelum ada peringkat

- Schengen Visa Application Form EnglishDokumen4 halamanSchengen Visa Application Form EnglishHatem FallouhBelum ada peringkat

- PQ Log MG 0119 m1.2Dokumen2 halamanPQ Log MG 0119 m1.2Marcio GarciaBelum ada peringkat

- Marciobio O1Dokumen2 halamanMarciobio O1Marcio GarciaBelum ada peringkat

- TRANSLATED Mercado Social MagazineDokumen4 halamanTRANSLATED Mercado Social MagazineMarcio GarciaBelum ada peringkat

- M Garcia Resume 2017Dokumen2 halamanM Garcia Resume 2017Marcio GarciaBelum ada peringkat

- Venetian Boat SongDokumen2 halamanVenetian Boat SongMarcio GarciaBelum ada peringkat

- J DIlla The GreatestDokumen1 halamanJ DIlla The GreatestMarcio GarciaBelum ada peringkat

- Urgent Action: Journalists Threatened and HarassedDokumen2 halamanUrgent Action: Journalists Threatened and HarassedMarcio GarciaBelum ada peringkat

- Fidelio QuartetDokumen7 halamanFidelio QuartetMarcio Garcia100% (2)

- Subscription Renewal Letter TemplateDokumen1 halamanSubscription Renewal Letter TemplateMarcio GarciaBelum ada peringkat

- TESTDokumen1 halamanTESTMarcio GarciaBelum ada peringkat

- Subscription Renewal Letter TemplateDokumen1 halamanSubscription Renewal Letter TemplateMarcio GarciaBelum ada peringkat

- All The Joy ChordsDokumen2 halamanAll The Joy ChordsMarcio Garcia100% (1)

- DimmerDokumen7 halamanDimmerGilberto ManhattanBelum ada peringkat

- Hua Yanjun (1893-1950) and Liu Tianhua (1895-1932)Dokumen11 halamanHua Yanjun (1893-1950) and Liu Tianhua (1895-1932)Mandy ChengBelum ada peringkat

- HOJA DE DATOS CORPORATIVA Cinepolis 2015Dokumen2 halamanHOJA DE DATOS CORPORATIVA Cinepolis 2015Mauricio Glez PadillaBelum ada peringkat

- TherionDokumen16 halamanTherionEmil MujevicBelum ada peringkat

- Post-colonial Drama of Mahesh DattaniDokumen31 halamanPost-colonial Drama of Mahesh DattanisanjeevBelum ada peringkat

- Kartik - Krishnan - CVDokumen3 halamanKartik - Krishnan - CVKartikKrishnanBelum ada peringkat

- Lauren-Jodie Wilson: Colab ReflectionDokumen4 halamanLauren-Jodie Wilson: Colab ReflectionLauren-Jodie WilsonBelum ada peringkat

- Rose Pedone Resume 2018Dokumen1 halamanRose Pedone Resume 2018api-343992908Belum ada peringkat

- Act 182 Theatres and Places of Public Amusement Federal Territory Act 1977Dokumen2 halamanAct 182 Theatres and Places of Public Amusement Federal Territory Act 1977Adam Haida & CoBelum ada peringkat

- B1 UNITS 7 and 8 Literature Teacher's NotesDokumen2 halamanB1 UNITS 7 and 8 Literature Teacher's NotesKerenBelum ada peringkat

- Why Should Riggers Have All The Fun?Dokumen20 halamanWhy Should Riggers Have All The Fun?IATSE100% (1)

- Huck Finn ScriptDokumen13 halamanHuck Finn ScriptMihnea Christian VladescuBelum ada peringkat

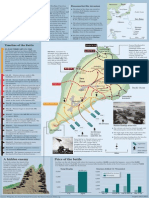

- IWOJIMA InfographicDokumen1 halamanIWOJIMA InfographicAnonymous rdyFWm9Belum ada peringkat

- Antigone PowerpointDokumen23 halamanAntigone Powerpointvernon whiteBelum ada peringkat

- Usan Glaspell and The Anxiety of Expression: Language and Isolation in The Plays.Dokumen5 halamanUsan Glaspell and The Anxiety of Expression: Language and Isolation in The Plays.franciscoBelum ada peringkat

- Rishika Singh CVDokumen1 halamanRishika Singh CVapi-425403549Belum ada peringkat

- ARTA Art of Emerging Europe2Dokumen2 halamanARTA Art of Emerging Europe2DanSanity TVBelum ada peringkat

- Introduction - Various Forms - Figures of SpeechDokumen32 halamanIntroduction - Various Forms - Figures of SpeechSherief DarwishBelum ada peringkat

- Aug. 29, 2016 Price $7.99Dokumen94 halamanAug. 29, 2016 Price $7.99corinabold5280Belum ada peringkat

- Ancient Art Analysis and EvaluationDokumen6 halamanAncient Art Analysis and EvaluationjamesBelum ada peringkat

- The Princess BrideDokumen2 halamanThe Princess BrideLynne WornallBelum ada peringkat