Nenet Shamanism - Keepers Clean Beasts

Diunggah oleh

Nicholas Breeze WoodHak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Nenet Shamanism - Keepers Clean Beasts

Diunggah oleh

Nicholas Breeze WoodHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

KEEPERS of the CLEAN BEASTS

Nenets Shamanism and the Reindeer

The Nenets people of the Western Siberian Arctic live on a flat area of frozen tundra, which in the summer thaws on the surface into what is, in effect, a giant bog. Theirs is a cold, desolate and featureless landscape, where, in the winter, temperatures can plummet to -50c; and yet they have lived there for centuries, establishing a rich culture, greatly influenced by their most important animal - the reindeer. The Nenets are a nomadic people, following their reindeers yearly migration of over a thousand kilometres. Today more than 10,000 nomads herd around 300,000 reindeer, living in family groups called brigades - a legacy from Soviet days. Each brigade is lead by a brigadier, who is the head of the family. The herders sell the reindeer meat and skins and also saw off the reindeers antlers which are exported to China for use in traditional medicine. Apart from its use for meat and skins, the reindeer form a central part of Nenets culture. One young herdsman, asked by an anthropologist why the young people like to live on the tundra and not in a village with all the advantages of civilisation such as TV, dance halls and bars, replied Ah, but in the village I don't have reindeer! The reindeer provide shelter - in the form of the tipi-like chum tent which is made of their skins. Traditional Nenets clothing is also made from reindeer skins, and reindeer are used pull sleighs, which are used on snow in the

Approx area of the Nenets people

winter and on the soft boggy ground in the summer. Reindeer also have a great social importance; for example, it is still common that a bride price in the form of reindeer is paid, and a dowry is brought to the young family when a tundra couple marries. But running under all of these as if a skeleton supporting the whole way of Nenets life - is the sacred nature of the reindeer. THE SACRED REINDEER The Nenets see the tundra and creatures that live on it as being alive and sacred, and the open tundra as being filled with spirits. The reindeer are the largest animal on the tundra and are seen almost as a royal beast by the Nenets. Reindeer are called the pure animal and this sense of purity is central to their view of the animal. Everything about a reindeer is considered pure and clean and treated with reverence, even its droppings. Reindeer do not have parasites, and the Nenets eat huge quantities of raw meat, still warm from the kill, and drink large quantities of warm fresh blood on a daily basis without suffering any health problems. They also consider their skins to be so pure that a Nenets wearing them can do without washing for months on end. The Nenets idea of the purity of the reindeer becomes clear when compared with their attitude towards their vitally important dogs. Dogs are an irreplaceable aid to the herdsman but their position is very low in the peoples eyes. Dogs are looked after to a certain extent - allowed to come into the chum to shelter from mosquitoes or the cold etc., but this is only because they are useful. For the Nenets, dogs are not pets, they are working tools, and they are considered dirty animals because they are smelly swallowers of anything, while the reindeer is a pure animal living mostly on clean moss. The Nenets sacrifice reindeer to the spirits, strangling them to avoid bloodshed, the head of the reindeer always made to look towards the sun as it dies, and this is to honour their most important spirit, Kog, (heaven). They also have living sacrificial reindeer too, sacred animals, generally castrated reindeer bulls, which are given to the spirits and

Above: Nenets herder with her reindeer Left: Nenets chum on the tundra

UK map to the same scale

Novy Port

38 SH

ISSUE 70 2010

Nenets mother and child

who protect the domestic space.

During migrations, these are carried on the sacred narta sledges, which are kept, when not in use, behind the brigadiers chum, pointing into the centre of the circular camp. The dolls are stored in the chum, once it has been erected, kept in a sacred shrine area within it, where they are fed vodka and blood when their help is needed. Several times a year the sacred narta sledge is also fed with fresh reindeer blood.

The Old Man and the Old Woman, ancestral ongon dolls of the home and the family. Nenet, wood, metal, fur and fabric. Late C19th

generally left to live their natural lives. These spirit animals are easily recognisable because unlike ordinary bulls, their antlers are not cut. The Nenets describe these animals as beautiful reindeer, as they are more often big and strong with exceptional fur. Within each herd there is normally a black animal which is dedicated to the powerful underworld spirit Kca. Kca is the spirit who sends diseases and death to the Earth, so if his reindeer is among the herd it will prevent the herd from becoming ill. If the Kca reindeer fails in its task, and the herd becomes infected, it will often be given as a blood sacrifice. Some reindeer are also given to Kog, the heavenly spirit, these are generally white reindeer. Another important sacred living animal is lcak azsna, or the wolf reindeer. This animal is usually of a greyish wolf-like colour, and it has a picture of a wolf drawn on its side with the blood of the previous wolf reindeer. This animal is dedicated to the master spirit of the wolves, and protects the herd from their pack: the wolves are said to understand that in the presence of this reindeer they are not allowed to attack the herd. DOLLS OF THE SACRED SLEDGE Every family has a special reindeer used to pull a narta (sacred sledge). This reindeer is a living offering to the ancestor spirits. The local spirits of the tundra, as well as ancestral spirits and other powerful influences in Nenets life, are traditionally represented in ongon dolls carved from wood and dressed in reindeer fur. These include the Old Woman and the Old Man of the chum, ancestral spirits

INFLUENCE OF CHRISTIANITY Christianity was often not far away from this part of Western Siberia, Russian Orthodox priests have been in the area in Russian settlements for centuries. They rarely ventured out onto the tundra, but the Nenets came into town for trade and the Church made an effort to convert them to its faith. Some shamanic traditions have become infused with elements of Christianity, special reindeer may have crucifixes tied around their necks, and crucifixes have, over the centuries, become part of the ritual equipment of some of the shamans. But because the priests rarely ventured out into the wilds, once the Nenets left the towns they quickly reverted back to their shamanic ways. During the 1840s one priest saw a baptised shaman performing a ceremony who explained, As Im baptised, I just beat my drum and call the spirits quietly, so that your Russian God will not hear my voice.

Nenets chum encampment

Nenets woman sewing

SH

ISSUE 70 2010

39

Right: Icon of Saint Nicholas. Russian, C19th

One aspect of Christianity that did catch on with the Nenets were some of the Christians helper spirits. Saint Nicholas, the Miracle Worker, is one of the main spirit helpers in Nenets cosmology. He is the assistant to Num, the Nenets main Upper World spirit, and lives on the fifth level of the Upper World. Icons of Saint Nicholas are one of the shamans' main means of communication with the Upper World, as the saint is the highest power whom a shaman has personally access to. Besides Saint Nicholas, Nenets shamans also communicate with Saint Elijah and the Virgin Mary. Saint Elijah is considered the patron saint of the reindeer, as is Saint George, who also features in Nenets cosmology. AN ENGLISH ACCOUNT Being reasonably close to major Russian cities, Nenets shamans were some of the very earliest ever encountered by Westerners. Below is an account of a Nenets shaman in ceremony, written by Richard Johnson, an English navigator, who in 1556 sailed on the ship Searchthrift looking for the north-east passage. And first the priest [shaman] doeth begin to play upon a thing like to a great sieve, with a skin on the one end like a drum: and the stick that he playeth with is about a span long, and one end is round like a ball, covered with the skin of a hart. Also the priest has upon his head a thing of white like a garland, and his face is covered with a piece of a shirt of mail, with many small rib, and teeth of fishes and wilde beasts hanging on the same mail.

Then he took a sword and put it into his belly halfway and sometime less, but no wound was to be seen

Then he singeth as we use here in England to hallow, whope or shout at hounds, and the rest of the company answer him. Then the priest replieth again with his voice, and they answer him with the selfsame words so many times, that in the end he becometh as it were mad, and falling down as he were dead, having nothing on him but a shirt, lying upon his back. I asked them why he lay so, and they answered me, now doeth our god tell him what we shall do, and whither we shall go. And when he had lay still a little while, they cried three times together, Oghao, Oghao, Oghao, and as they use these three calls, he rose up and sang with like voices as he did before, and his audience answered him. Then he commanded them to kill five great deer, and continued singing, still both he and they, as before. Then he took a sword of a cubit and a span long, (I did measure it myself) and put it into his belly halfway and sometime less, but no wound was to be seen, (they continuing in their sweet song still). Then he put the sword into the fire till it was warm, and so thrust it into the slit of his shirt and thrust it through his body, as I thought, in at his navel and out at his fundament: the point being out of his shirt behind. I layed my finger upon it, then he pulled out the sword and sat down. This being done, they set a kettle of water over the fire to heat, and when the water doeth seeth, the priest beginneth to sing again, they answering him. Then they made a thing being four square, and in height and squareness of a chair, and covered with a gown. The water still seething on the fire, and this square seat being ready, the priest put off his shirt, and the thing like a garland which was on his head, with those things which covered his face. So he went into the square seat, and sat down like a tailor and sang with a strong voice. Then they took a small line made of

Below: traditional Nenets womans costume

deer skin of four fathoms long, and with a smal knot the priest made it fast about his neck, and under his left arm, and gave it unto two men standing on both sides of him, which held the ends together. Then the kettle of hot water was set before him, and [the shaman] was covered with a gown of broadcloth without lining, such as the Russes do wear. Then the two men which did hold the ends of the line still, began to draw, and drew till they had drawn the ends of the line stiff and together, and then I heard a thing fall into the kettle of water which was before him. Thereupon I asked them, that sat by me, what it was that fell into the water that stood before him, and they answered me, that it was his head, his shoulder and left arm, which the line had cut off. Then I rose up and would have looked whether it were so or not, but they laid hold on me, and said, that if they should see him with their bodily eyes, they should live no longer. Then they began to halow with these wordes, Oghaoo, Oghaoo, Oghaoo, many times together, and as they were thus singing and out calling, I saw a thing like a finger of a man two times together thrust through the gown from the priest. I asked them that sat next to me what it was that I saw, and they said, not his finger; for he was yet dead; and that which I saw appear through the gown was a beast, but what beast they knew not nor would not tell. And I looked upon the gown, and there was no hole to be seen. And then at the last the priest lifted up his head with his shoulder and arm, and all his body, and came forth to the fire. This I saw, the fifth day of January in the year of our Lord 1556.

40 SH

ISSUE 70 2010

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- 3916 West Kennet Eval 12227 Complete PDFDokumen24 halaman3916 West Kennet Eval 12227 Complete PDFJoseph Speed-MettBelum ada peringkat

- Cave 74 01 PDFDokumen136 halamanCave 74 01 PDFalegria1975Belum ada peringkat

- Medieval Warm Period RussiaDokumen13 halamanMedieval Warm Period RussiaAntiKleptocratBelum ada peringkat

- Neolithic RevolutionDokumen22 halamanNeolithic RevolutionFiruzaBelum ada peringkat

- 'The Awen' Spring & Beltane 2011Dokumen88 halaman'The Awen' Spring & Beltane 2011kellie0100% (2)

- The History of The Treman, Tremaine, Truman Family in AmericaDokumen1.324 halamanThe History of The Treman, Tremaine, Truman Family in AmericaJakob AyresBelum ada peringkat

- Hawthorn Flour Recipe From BritainDokumen2 halamanHawthorn Flour Recipe From BritainLinda PrideBelum ada peringkat

- History of The Native Woodlands of ScotlandDokumen465 halamanHistory of The Native Woodlands of Scotlandpiugabi100% (1)

- Natural History in the Highlands and IslandsDari EverandNatural History in the Highlands and IslandsPenilaian: 3 dari 5 bintang3/5 (5)

- Old Ways New Roads: Travels in Scotland 1720–1832Dari EverandOld Ways New Roads: Travels in Scotland 1720–1832John BonehillBelum ada peringkat

- New Light On Neolithic Revolution in South-West Asia - Trevor Watkins, Antiquity 84 (2010) : 621-634.Dokumen14 halamanNew Light On Neolithic Revolution in South-West Asia - Trevor Watkins, Antiquity 84 (2010) : 621-634.Trevor WatkinsBelum ada peringkat

- Australian FloraDokumen2 halamanAustralian Florabobsterman100% (1)

- IRISH WONDER TALES - 14 Enchanting tales from the Emerald Isle: 14 Enchanting Celtic Children's StoriesDari EverandIRISH WONDER TALES - 14 Enchanting tales from the Emerald Isle: 14 Enchanting Celtic Children's StoriesBelum ada peringkat

- Golden Gate Gardening Pam PierceDokumen3 halamanGolden Gate Gardening Pam PierceMichaelBelum ada peringkat

- Geo-Cultural Time: Advancing Human Societal Complexity Within Worldwide Constraint Bottlenecks-A Chronological/Helical Approach To Understanding Human-Planetary Interactions (Gunn, 2019)Dokumen19 halamanGeo-Cultural Time: Advancing Human Societal Complexity Within Worldwide Constraint Bottlenecks-A Chronological/Helical Approach To Understanding Human-Planetary Interactions (Gunn, 2019)CliffhangerBelum ada peringkat

- Ancient PlantsDokumen222 halamanAncient PlantsPaola MartinezBelum ada peringkat

- Journey into the Temples of Humankind: The Extraordinary, Subterranean Work of Art Dedicated to Spirituality, Harmony and BeautyDari EverandJourney into the Temples of Humankind: The Extraordinary, Subterranean Work of Art Dedicated to Spirituality, Harmony and BeautyBelum ada peringkat

- Holy WellsDokumen12 halamanHoly WellsscrobhdBelum ada peringkat

- The Last Kids On Earth Discussion GuideDokumen1 halamanThe Last Kids On Earth Discussion GuideYaya QugieBelum ada peringkat

- The Astronomy of Indigenous AustraliansDokumen10 halamanThe Astronomy of Indigenous AustraliansPurdy MatthewsBelum ada peringkat

- Bar Yosef - Natufian Culture in The LevantDokumen19 halamanBar Yosef - Natufian Culture in The LevantNeolitička ŠlapaBelum ada peringkat

- The Sauchie Poltergeist (And other Scottish ghostly tales)Dari EverandThe Sauchie Poltergeist (And other Scottish ghostly tales)Belum ada peringkat

- Cannock Chase GeologyDokumen30 halamanCannock Chase Geologypeter_alford3209Belum ada peringkat

- Levy - Laurence Green Laurence February 20Dokumen61 halamanLevy - Laurence Green Laurence February 20Murray LaurenceBelum ada peringkat

- Orkneyinga Saga The History of The Earls of Orkney (Hermann Palsson, Paul Edwards)Dokumen236 halamanOrkneyinga Saga The History of The Earls of Orkney (Hermann Palsson, Paul Edwards)Kacper KwiatekBelum ada peringkat

- Ethnobotanic Resources of Tropical Montane Forests: Indigenous Uses of Plants in the Cameroon Highland EcoregionDari EverandEthnobotanic Resources of Tropical Montane Forests: Indigenous Uses of Plants in the Cameroon Highland EcoregionBelum ada peringkat

- The Neanderthals: Who Were They and How did They LiveDari EverandThe Neanderthals: Who Were They and How did They LivePenilaian: 5 dari 5 bintang5/5 (1)

- The Ice Age Rise and Fall of The Ponto Caspian, Ancient Mariners and The Asiatic MediterraneanDokumen17 halamanThe Ice Age Rise and Fall of The Ponto Caspian, Ancient Mariners and The Asiatic Mediterraneankurgan2Belum ada peringkat

- Irish Myths and LegendsDokumen4 halamanIrish Myths and Legendsanyus1956Belum ada peringkat

- Ruthenberg Farming Systems in The Tropics PDFDokumen344 halamanRuthenberg Farming Systems in The Tropics PDFDhamma_Storehouse100% (1)

- Stonehenge ENGDokumen19 halamanStonehenge ENGOsiel HdzBelum ada peringkat

- Myths of the Norsemen From the Eddas and SagasDari EverandMyths of the Norsemen From the Eddas and SagasPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (69)

- Into the Secret Heart of Ashdown Forest: A Horseman's Country DiaryDari EverandInto the Secret Heart of Ashdown Forest: A Horseman's Country DiaryBelum ada peringkat

- Lancashire Folk-lore Illustrative of the Superstitious Beliefs and Practices, Local Customs and Usages of the People of the County PalatineDari EverandLancashire Folk-lore Illustrative of the Superstitious Beliefs and Practices, Local Customs and Usages of the People of the County PalatineBelum ada peringkat

- The Natufian Culture in The Levant, Threshold To The Origins of AgricultureDokumen19 halamanThe Natufian Culture in The Levant, Threshold To The Origins of Agriculture14johannes100% (1)

- Women-Centered Holidays from Around the World | Children's Holiday BooksDari EverandWomen-Centered Holidays from Around the World | Children's Holiday BooksBelum ada peringkat

- Doctrine of Signatures Mystic Heritage or Outdated Relict From MiddleagedphytotherapyDokumen3 halamanDoctrine of Signatures Mystic Heritage or Outdated Relict From Middleagedphytotherapyadequatelatitude1715100% (1)

- Rodney Harrison: Heritage. Critical Approaches - London: Routledge, 2013. 268 Pp. ISBN: 978-0-415-59197-3Dokumen5 halamanRodney Harrison: Heritage. Critical Approaches - London: Routledge, 2013. 268 Pp. ISBN: 978-0-415-59197-3Magdalena MedicBelum ada peringkat

- Science Poetry ParksDokumen333 halamanScience Poetry ParksTaylor JohnsBelum ada peringkat

- FENTON, WILLIAM N. - Iroquois Journey, An Anthropologist Remembers. (2007)Dokumen224 halamanFENTON, WILLIAM N. - Iroquois Journey, An Anthropologist Remembers. (2007)Utentes BlxBelum ada peringkat

- Reindeer BookletDokumen16 halamanReindeer BookletAlejandra HernándezBelum ada peringkat

- Changing Pictures: Rock Art Traditions and Visions in the Northernmost EuropeDari EverandChanging Pictures: Rock Art Traditions and Visions in the Northernmost EuropeJoakim GoldhahnPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1)

- Folk-Lore and LegendsScotland by AnonymousDokumen67 halamanFolk-Lore and LegendsScotland by AnonymousGutenberg.orgBelum ada peringkat

- Spirit Sight: Epic fantasy in medieval Wales (Last of the Gifted - Book One)Dari EverandSpirit Sight: Epic fantasy in medieval Wales (Last of the Gifted - Book One)Belum ada peringkat

- The Hidden and Forgotten Temples of Malta: A Journey of DiscoveryDari EverandThe Hidden and Forgotten Temples of Malta: A Journey of DiscoveryBelum ada peringkat

- Reinventing Sustainability: How Archaeology can Save the PlanetDari EverandReinventing Sustainability: How Archaeology can Save the PlanetBelum ada peringkat

- Beads of IntentDokumen4 halamanBeads of IntentNicholas Breeze WoodBelum ada peringkat

- The Mongolian Ger - YurtDokumen4 halamanThe Mongolian Ger - YurtNicholas Breeze WoodBelum ada peringkat

- Native American Trade BlanketsDokumen4 halamanNative American Trade BlanketsNicholas Breeze WoodBelum ada peringkat

- Kutchas Children by Nicholas Breeze Wood and Sacred Hoop MagazineDokumen5 halamanKutchas Children by Nicholas Breeze Wood and Sacred Hoop MagazineNicholas Breeze WoodBelum ada peringkat

- Dinn - Shamanic Spirits of IslamDokumen3 halamanDinn - Shamanic Spirits of IslamNicholas Breeze Wood100% (1)

- Nicholas Breeze Wood Explores Tibetan Use of Human BoneDokumen4 halamanNicholas Breeze Wood Explores Tibetan Use of Human BoneNicholas Breeze Wood67% (3)

- The Soul of The ShamanDokumen4 halamanThe Soul of The ShamanNicholas Breeze Wood100% (1)

- Statement of The Problem: Notre Dame of Marbel University Integrated Basic EducationDokumen6 halamanStatement of The Problem: Notre Dame of Marbel University Integrated Basic Educationgab rielleBelum ada peringkat

- Astrology - House SignificationDokumen4 halamanAstrology - House SignificationsunilkumardubeyBelum ada peringkat

- Final Key 2519Dokumen2 halamanFinal Key 2519DanielchrsBelum ada peringkat

- Research PhilosophyDokumen4 halamanResearch Philosophygdayanand4uBelum ada peringkat

- February / March 2010Dokumen16 halamanFebruary / March 2010Instrulife OostkampBelum ada peringkat

- AI Capstone Project Report for Image Captioning and Digital AssistantDokumen28 halamanAI Capstone Project Report for Image Captioning and Digital Assistantakg29950% (2)

- Ten - Doc. TR 20 01 (Vol. II)Dokumen309 halamanTen - Doc. TR 20 01 (Vol. II)Manoj OjhaBelum ada peringkat

- An Analysis of Students Pronounciation Errors Made by Ninth Grade of Junior High School 1 TengaranDokumen22 halamanAn Analysis of Students Pronounciation Errors Made by Ninth Grade of Junior High School 1 TengaranOcta WibawaBelum ada peringkat

- Contextual Teaching Learning For Improving Refrigeration and Air Conditioning Course On The Move To Prepare The Graduates To Be Teachers in Schools of International LevelDokumen15 halamanContextual Teaching Learning For Improving Refrigeration and Air Conditioning Course On The Move To Prepare The Graduates To Be Teachers in Schools of International LevelHartoyoBelum ada peringkat

- Opportunity, Not Threat: Crypto AssetsDokumen9 halamanOpportunity, Not Threat: Crypto AssetsTrophy NcBelum ada peringkat

- Ellen Gonzalvo - COMMENTS ON REVISIONDokumen3 halamanEllen Gonzalvo - COMMENTS ON REVISIONJhing GonzalvoBelum ada peringkat

- UG022510 International GCSE in Business Studies 4BS0 For WebDokumen57 halamanUG022510 International GCSE in Business Studies 4BS0 For WebAnonymous 8aj9gk7GCLBelum ada peringkat

- Maternity and Newborn MedicationsDokumen38 halamanMaternity and Newborn MedicationsJaypee Fabros EdraBelum ada peringkat

- RA 4196 University Charter of PLMDokumen4 halamanRA 4196 University Charter of PLMJoan PabloBelum ada peringkat

- Corporate Law Scope and RegulationDokumen21 halamanCorporate Law Scope and RegulationBasit KhanBelum ada peringkat

- Kids' Web 1 S&s PDFDokumen1 halamanKids' Web 1 S&s PDFkkpereiraBelum ada peringkat

- Economic Impact of Tourism in Greater Palm Springs 2023 CLIENT FINALDokumen15 halamanEconomic Impact of Tourism in Greater Palm Springs 2023 CLIENT FINALJEAN MICHEL ALONZEAUBelum ada peringkat

- Write a composition on tax evasionDokumen7 halamanWrite a composition on tax evasionLii JaaBelum ada peringkat

- What Blockchain Could Mean For MarketingDokumen2 halamanWhat Blockchain Could Mean For MarketingRitika JhaBelum ada peringkat

- Excel Keyboard Shortcuts MasterclassDokumen18 halamanExcel Keyboard Shortcuts MasterclassluinksBelum ada peringkat

- Factors Affecting English Speaking Skills of StudentsDokumen18 halamanFactors Affecting English Speaking Skills of StudentsRona Jane MirandaBelum ada peringkat

- BI - Cover Letter Template For EC Submission - Sent 09 Sept 2014Dokumen1 halamanBI - Cover Letter Template For EC Submission - Sent 09 Sept 2014scribdBelum ada peringkat

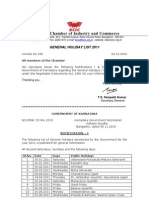

- BCIC General Holiday List 2011Dokumen4 halamanBCIC General Holiday List 2011Srikanth DLBelum ada peringkat

- AFRICAN SYSTEMS OF KINSHIP AND MARRIAGEDokumen34 halamanAFRICAN SYSTEMS OF KINSHIP AND MARRIAGEjudassantos100% (2)

- Bianchi Size Chart for Mountain BikesDokumen1 halamanBianchi Size Chart for Mountain BikesSyafiq IshakBelum ada peringkat

- Contract Costing and Operating CostingDokumen13 halamanContract Costing and Operating CostingGaurav AggarwalBelum ada peringkat

- 110 TOP Survey Interview QuestionsDokumen18 halaman110 TOP Survey Interview QuestionsImmu100% (1)

- Independent Study of Middletown Police DepartmentDokumen96 halamanIndependent Study of Middletown Police DepartmentBarbara MillerBelum ada peringkat

- Sergei Rachmaninoff Moment Musicaux Op No in E MinorDokumen12 halamanSergei Rachmaninoff Moment Musicaux Op No in E MinorMarkBelum ada peringkat

- Autos MalaysiaDokumen45 halamanAutos MalaysiaNicholas AngBelum ada peringkat