ESWL

Diunggah oleh

Mustika Dwi SusilowatiDeskripsi Asli:

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

ESWL

Diunggah oleh

Mustika Dwi SusilowatiHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Upper Urinary Tract LONG-TERM OUTCOME OF CALYCEAL DIVERTICULAR STONES TURNA et al.

In this section this month, we have two papers. The rst is from authors from Scotland. They present a review of patients with an extended follow-up who have undergone extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy (ESWL) or percutaneous nephrolithotomy (PCNL) for calyceal diverticular stones over a 15-year period to assess long-term outcome, irrespective of treatment. They concluded that PCNL is an effective and durable means of treating calyceal diverticular stones, regardless of stone size or location of the diverticulum. Despite low stone-free rates with ESWL, most patients are rendered symptom-free with minimal complications. The second paper is from the USA; the authors discuss the new generation of exible ureteroscopes, which provide exaggerated active deection to facilitate intrarenal manipulation. They compared the relative ease of manipulation around a calyceal model. The authors concluded that the Wolf Viper proved superior for manipulation in the hands of experienced endoscopists.

Management of calyceal diverticular stones with extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy and percutaneous nephrolithotomy: long-term outcome

Burak Turna, Asif Raza, Sami Moussa, Gordon Smith and David A. Tolley

Department of Urology and Scottish Lithotriptor Centre, Western General Hospital, Edinburgh, UK

Accepted for publication 25 January 2007

OBJECTIVE To review patients with an extended followup after extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy (ESWL) or percutaneous nephrolithotomy (PCNL) for calyceal diverticular stones (CDS), over a 15-year period, assessing the longterm outcome. PATIENTS AND METHODS In all, 56 patients were treated for symptomatic CDS disease by ESWL (38) or PCNL (18). The stone-bearing diverticula were in the upper calyces in 26, middle calyces in 24 and lower calyces in six patients, and in the right kidney in 22 and in the left in 34. The most frequent symptom was ipsilateral ank pain (84%) and 32% of patients presented with associated chronic urinary tract infections. In a retrospective analysis, we assessed stone size, diverticulum location, stone-free rate, symptom-free rate, complications and extended follow-up. RESULTS In the short-term in the ESWL group, 21% of patients were stone-free and 61% were asymptomatic; 8% developed symptoms and 8% developed recurrence or stone-growth

in the long term. There were six minor complications. In the PCNL group, 15 patients (83%) were stone-free in the short term; two had a recurrence (11%) and two had stone growth (11) in the long term. There were three complications after PCNL. CONCLUSIONS This series shows that PCNL is an effective and durable means of treating CDS, regardless of stone size or location of the diverticulum. Despite low stone-free rates with ESWL, most patients were rendered symptom-free with minimal complications. The long-term recurrence rates, 8% for ESWL and 11% for PCNL, were comparable. KEYWORDS calyces, diverticulum, calculi, percutaneous nephrolithotomy, ESWL

INTRODUCTION Calyceal diverticula are urine-lled intrarenal cavities of an embryonic aetiology with a transitional epithelial lining connected to the normal pelvicalyceal collecting system by a narrow isthmus [1]. They usually arise from

2 0 07 T H E A U T H O R S

JOURNAL COMPILATION

2 0 0 7 B J U I N T E R N A T I O N A L | 1 0 0 , 1 5 1 1 5 6 | doi:10.1111/j.1464-410X.2007.06911.x

151

T U R N A ET AL.

the fornix of a calyx and might develop in any calyx from the posterior or anterior aspect of the renal collecting system. Diverticula are often detected incidentally on IVU and have an incidence of <1% [2]. They are usually asymptomatic but they can cause infection, stone formation, abscess formation, sepsis and haematuria. The incidence of calculi within calyceal diverticula is reportedly 1050% [3]. Indications for treatment include pain, recurrent infection, increased stone growth, haematuria or a large size that compresses or progressively damages contiguous renal parenchyma. There are various potentially therapeutic methods, e.g. ESWL, percutaneous nephrolithotomy (PCNL), ureterorenoscopic management (URS), laparoscopic and open surgery. As calyceal diverticular stone (CDS) disease is a rare entity there is no consensus on management. The principal minimally invasive alternative to ESWL in treating CDS is PCNL. We present a review of patients with an extended follow-up who had ESWL or PCNL for CDS over a 15-year period, to assess the long-term outcome, irrespective of treatment. To our knowledge, this series represents the most patients with the longest follow-up after ESWL or PCNL for CDS. PATIENTS AND METHODS Between September 1989 and January 2004, 56 patients (25 men and 31 women) were treated for symptomatic CDS disease by ESWL or PCNL, by the same team at our institution. The treatment decision was based on the symptoms, stone burden and patency of the diverticular isthmus, as well as patient choice. Notably, the main selection criteria for treatment was stone size; patients with stones of <1 cm with radiologically patent diverticular necks usually had ESWL, whereas patients with stones of >1 cm and/or a stenotic neck were often treated by PCNL. A radiographically patent diverticular neck was dened as clear visualization of the diverticular neck on IVU. Flexible URS was typically used as a salvage procedure. The treatment decision was under the supervision of the same consultants during the study period. In all, 38 patients (16 men and 22 women) with calculi in 38 calyceal diverticula were treated with ESWL, using the Piezolith 2300

(198999; Richard Wolf GmbH, Germany) and the Compact Delta (19992002; Dornier GmbH, Germany) lithotripters, with the patient under sedo-analgesia when necessary. The same team was involved in operating the two lithotripters. During the same period, 18 patients (nine men and nine women) had PCNL for symptomatic CDS disease; none had had previous ESWL. For all PCNL procedures the patients were under general anaesthesia and prone. The endosurgical technique used to treat most patients involved initial placement of a retrograde 6 F open-end ureteric catheter into the renal pelvis. The percutaneous access to the calyceal diverticulum was direct and under uoroscopic guidance. The tract was dilated to 30 F with Alken serial dilators, followed by placing a 30 F Amplatz sheath. Then a 24.5 F nephroscope was inserted and the stones were fragmented and aspirated using an ultrasonic lithotripter. When all stones were cleared, 10 mL of salinediluted methylene blue was injected to identify the calyceal diverticular neck. Then dilatation/incision of the diverticular neck was attempted either with Amplatz dilators (usually up to 22 F) or by holmium laser. No effort was made to fulgurate the diverticular cavity. On completing the procedure, an 8 F pigtail nephrostomy tube was placed in the diverticulum until a postoperative nephrostogram showed no extravasation of contrast material. The stone-free status was determined by the immediate uoroscopic and endoscopic view. Patients treatment records and follow-up information were all recorded prospectively in a computer database. Information was entered exclusively by the same team of staff performing the lithotripsy and endourological procedures, thus maintaining consistency and standard input. Patients were followed by plain radiography, ultrasonography and/or IVU 3 months after the treatment and yearly thereafter; thus, the short-term follow-up was determined by the 3 month follow-up. Treatment outcomes for lithotripsy were good fragmentation, stonefree and symptom-free, dened as evidence of complete fragmentation on uoroscopy, absence of radiological evidence of stone on plain radiography at 3 months, and clinical disappearance of existing symptoms, respectively.

We used a retrospective analysis including stone size, diverticulum location, stone-free rate, symptom-free rate, complications and extended follow-up, in an attempt to assess the long-term outcome. The long-term subjective and objective follow-up from the last treatment date until the study date was obtained from all patients.

RESULTS The characteristics of the patients are shown in Table 1; the stone-bearing diverticula were in the upper calyces in 26, middle calyces in 24 and lower calyces in six patients, and in the right kidney in 22 and in the left kidney in 34. The most frequent symptom was ipsilateral ank pain (84%) in 47 patients and 18 (32%) also presented with associated chronic UTIs. Most of these patients had been chronically symptomatic for a mean (range) of 15 (660) months. In the ESWL group, the mean (range) number of shock waves given per session was 3070 (20004000), and the sessions per patient was 1.6 (16). Initial follow-up with plain radiography and ultrasonography was obtained from all patients at 3 months after treatment. There were transient minor complications in six patients, including temporary ank pain in two and fever and associated UTIs in four; all settled with conservative medical treatment. At the initial 3-month follow-up only eight patients (21%) were radiographically stone-free; the stonefree rate in the upper, middle and lower pole diverticula was 25%, 19% and 0%, respectively. Of the 38 patients, good fragmentation was achieved in 33 (87%); 23 (61%) of the 38 with presenting symptoms were asymptomatic at the 3-month follow-up, including those with residual stone gravel. However, of the remaining 15 (39%) symptomatic patients with residual calculi, eight required PCNL and four had URS for denitive treatment; the remaining three were managed conservatively. All patients were available for the extended follow-up at a mean (range) of 23.3 (3110) months; radiographs showed persistence of the diverticulum in all patients treated by ESWL. Of the eight patients who had been stone-free at the initial follow-up, seven remained so. One

152

JOURNAL COMPILATION

2 0 07 T H E A U T H O R S

2 0 07 B J U I N T E R N AT I O N A L

LONG-TERM OUTCOME OF CALYCEAL DIVERTICULAR STONES

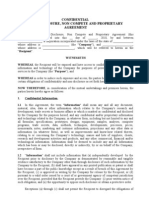

TABLE 1 The outcome of ESWL and PCNL for CDS Variable Number of patients Mean (range) age, years M/F, n Stone side (R/L), n Mean (range) stone size, mm Diverticulum location, n Upper pole Middle pole Lower pole Stone-free rate, % Fragmentation rate, % Asymptomatic residual fragments (<4 mm) rate, % Symptom-free rate, % Symptomatic improvement and/or symptom-free rate, % Complication rate, % Mean (range) follow-up, months Further intervention, n URS PCNL Recurrence, n Stone-free group Residual stone group ESWL 38 54.7 (1782) 16/22 15/23 11.7 (430) 20 16 2 21 87 40 61 16 23.3 (3110) 4/15 8/15 1/8 0/3 (conservative) 0/12 (further intervention) 2/15 (ESWL only) 2/15 2/3 (stone growth) PCNL 18 45.8 (2670) 9/9 7/11 20.6 (560) 6 8 4 83 83 94 17 48.3 (12144)

DISCUSSION It is well documented that some patients with CDS will benet from treatment with ESWL. Stone-free rates of 2058% can be achieved in well-documented series [46]. Psihramis and Dretler [4] reported a 20% stone freerate at the initial follow-up and noted symptomatic improvement even with the presence of residual calculi. In 1990 Ritchie et al. [5] reported their results of CDS treated with ESWL; their stone-free rate was 25% with a mean follow-up of 4 months, and they noted a 75% symptomatic improvement irrespective of stone-free status. These results show that although the stone-free rate with ESWL is low, symptomatic improvement is much higher. Streem and Yost [6] then reported higher stone-free rates (58%) in patients with CDS treated with ESWL. They suggested that by limiting this treatment to patients with relatively small calculi (<1.5 cm) and a patent diverticular neck, stone-free rates could be relatively high. However, despite these reports of acceptable stone-free rates and symptomatic improvement, ESWL has remained controversial for treating CDS. The theory that an anatomically narrow diverticular neck is not necessarily a physiologically obstructing lesion, and the concept that some diverticula are acquired lesions, would suggest that at least in some cases treating stones with ESWL alone might be effective [3,68]. There are various options for managing symptomatic CDS, each useful in particular situations. However, the present patients included those treated in 1980s and 1990s, when there were fewer minimally invasive treatment options. However, all of the patients were followed closely in one institution under the supervision of a senior urology consultant, and thus reporting was possible for this large number of patients with a long-term follow-up. From the present study, several conclusions can be drawn about ESWL treatment; although only some patients were rendered stone-free, most were rendered symptomfree after ESWL treatment. Symptom-free does not necessarily mean stone-free, but the stone-free status is always associated with symptom-free status. The extended follow-up showed that stone-growth or recurrent stone

patient had a recurrence of a small stone at 27 months and was treated by further ESWL. Fifteen of the 23 patients rendered symptomfree initially had remaining stone gravel, of whom three developed further recurrent UTI at a mean follow-up of 25 months; they were all managed conservatively. In addition, two of the 15 patients developed an increasing stone burden at a mean follow-up of 17 months, and they both had PCNL and were rendered stone-free. None of the 12 patients who required further interventions (PCNL, eight; URS four) developed further episodes of symptoms or recurrence or stonegrowth. Overall, 21% of patients were stonefree and 61% were asymptomatic in the short-term; 8% developed symptoms and 8% developed recurrence or stone growth in the long term. Percutaneous endosurgical stone extraction from calyceal diverticula was successful in 17 of the 18 patients (Table 1); direct percutaneous access under uoroscopy was used in all but dilatation and/or incision of the diverticular neck was used only in seven. In 10 patients the diverticular neck was not ablated,

due to a difcult anterior location of the diverticulum in three, intraoperative local haemorrhage in three, intraoperative observation of a patent neck in two and for unknown reasons in two. There was bleeding (during surgery) necessitating blood transfusion in two patients. Pneumothorax, managed by temporary chest-tube insertion, occurred in one patient. None developed atelectasis, pulmonary embolus, persistent fever or chronic infection after surgery. In the one patient where this approach failed, URS was used for an anteriorly located upper calyceal diverticula. Two patients had remaining small fragments after the procedure; both developed further stonegrowth at a mean follow-up of 49 months but were successfully (both stone-free) treated by ESWL. All 15 stone-free patients reported resolution of their symptoms at 3 months, and two of three with residual stones reported symptomatic improvement of their pain. Overall, 15 patients (83%) were stonefree, two had minor and one had major complications, two had a recurrence (11%) and two had a stone-growth (11%). All patients remain under surveillance.

2 0 07 T H E A U T H O R S

JOURNAL COMPILATION

2 0 07 B J U I N T E R N AT I O N A L

153

T U R N A ET AL.

formation is clearly not inevitable after ESWL, and that initial treatment using ESWL does not compromise the likelihood of successful treatment with either URS or PCNL. Interestingly, none of this group of patients developed further stone recurrences or growths in the long term, showing the durable success ( 2 years) of treatment. Therefore, we think it is reasonable to offer primary ESWL to selected patients with CDS, as an initial treatment (those requiring/opting for a noninvasive outpatient treatment for symptomatic small stones in a calyceal diverticulum with a clearly patent neck). Our clinical experience (61% symptom-free rate, 8% recurrence rate and no major complications) suggests that ESWL might be an alternative treatment when there is a small stone burden (<1 cm) with a short and patent diverticular neck. Some possible explanations for achieving symptom-free status in the presence of stone gravel might be due to the placebo effect and/or stone gravel (dust) not causing renal pain as much as unbroken stone material. Radio-anatomical studies show that the calyceal diverticulum is a rare anomaly, which becomes symptomatic when lled by a stone; it also acts as a reservoir for chronic UTIs. A literature search for studies of PCNL treatment for stone-bearing calyceal diverticula suggests that stone-free rates are 70100%, with recurrence rates of 030%, persistence of a stone of 020% and persistence of a diverticulum of 044% [812]. In the present study, PCNL treatment gave a stone-free rate of 83%, with a recurrence rate of 11% and persistence of a stone of 17%. In the present patients, followup IVU was not available for all but there was documentation of a persisting diverticulum in 11. However, in our series, although the diverticulum neck and cavity were not obliterated in most cases, the recurrence rate was low over a follow-up of >4 years. This supports the theory that an anatomically narrow diverticular neck is not necessarily a physiologically obstructing lesion. Shalhav et al. [13] reported the long-term outcome of calyceal diverticula after percutaneous endosurgical management in 30 patients, of whom 26 had stones. The stone-free rate was 93%, with obliteration of the diverticulum in 76% of patients. Overall, 85% of patients were asymptomatic with at a mean follow-up of 3.5 years.

Later, Landry et al. [14] reported the results of percutaneous treatment of CDS and concluded that at 1 year the stone-free rate was 84% and the diverticulum remained obliterated in 68% of patients. Overall, 88% of patients were asymptomatic at a mean follow-up of 24.6 months. The present series demonstrated that stone-free rate (PCNL) was 83% and the long-term follow-up suggested that most patients remained asymptomatic at 4 years. The extended follow-up showed a 11% recurrence rate and 11% stonegrowth rate, suggesting that if the initial procedure is successful the long-term outcome is durable. Percutaneous management of the calyceal diverticulum is challenging because the cavity is usually small and identifying the diverticular neck is often difcult. In the present 18 patients treated with PCNL, dilatation/incision of the diverticular neck was possible only in seven. Auge et al. [15] described an alternative approach if the infundibular connection to the renal collecting system could not be found. In that series of 21 patients, percutaneous management of complex calyceal diverticula with the neo-infundibulotomy technique provided a safe and effective option for symptomatic patients. Recently Kim et al. [16] reported results of PCNL for CDS using a single-stage approach in 21 patients. They concluded that in patients with symptomatic radio-opaque CDS, a single-stage procedure with no need for ureteric catheterization, combined with direct infracostal diverticular puncture, allowed for a rapid recovery with little morbidity. In the present study there were complications in six patients (16%) with ESWL and in three (17%) with PCNL; Skolarikis et al. [17] provided an extensive review of ESWLrelated complications and their prevention. A minimally invasive PCNL technique was introduced for use in children and adults with reduced renal reserve, to minimize the morbidity and preserve renal function [18]. From a technical standpoint, applying the miniperc technique in the percutaneous management of CDS might be an attractive method, but to date there are no published data suggesting that the miniperc technique causes less renal damage in the short- or long-term than standard PCNL. Although metabolic evaluation is an important aspect of managing urinary

tract stones, unfortunately we were unable to provide this information in the present patients who were treated over a long period. Two studies addressed this issue, with conicting results; Liatsikos et al. [19] found a low incidence of associated metabolic abnormalities in patients with CDS, stating that metabolic abnormalities did not promote CDS formation. However, in another study by Auge et al. [20], all patients with symptomatic CDS who had a comprehensive metabolic evaluation had metabolic abnormalities. Therefore, these authors recommended that, for patients with symptomatic CDS, a metabolic evaluation should be considered to determine risk factors for stone formation. The URS management of CDS disease yielded poor results for stone-free rate (1958%), symptom-free rate (3569%) and diverticular obliteration status ( 20%) [21,22]. Major problems encountered were identifying diverticular necks (especially in the lower pole) and maintaining adequate deection of the ureterorenoscope. In the present series, although URS was a useful ancillary procedure for failed percutaneous surgery and unsuccessful ESWL, successful URS as a sole method should be limited to upper or middle calyceal diverticula with a small stone burden and short accessible diverticular neck [21,22]. Available data suggest that a large stone mass seems to be the main inuencing factor for the stone-free rate in the URS management of CDS. Laparoscopic management of symptomatic calyceal diverticula has been increasingly reported as an effective technique for fulguration, ideally when thin parenchyma overlies the diverticulum. Miller et al. [23] reported a complete stone-free rate and complete diverticular obliteration in ve patients. Furthermore, Ramakumar et al. [24] reported 11 patients stone-free, eight symptom-free and 11 with diverticular obliteration in 12 patients. Wong et al. [25] recently described their technique of laparoscopy-assisted transperitoneal PCNL for renal CDS, and concluded that this technique was a safe and effective alternative for managing symptomatic stones in anterior cystic calyceal diverticula with a narrow neck and complex branched calculi. However, laparoscopic diverticulectomy is far more invasive than percutaneous surgery, and should be limited to peripherally located, large diverticula in anterior calyces with minimal overlying parenchyma.

154

JOURNAL COMPILATION

2 0 07 T H E A U T H O R S

2 0 07 B J U I N T E R N AT I O N A L

LONG-TERM OUTCOME OF CALYCEAL DIVERTICULAR STONES

In brief, the present study provides results for one of the longest follow-ups after ESWL and/ or PCNL treatment for CDS. Although the study was retrospective, information contained in the computer database was prospectively recorded. Furthermore, the results can be criticised because there were unequal numbers of patients in each group. Moreover, the symptom improvement was not measured with validated questionnaires. However, CDS disease is very rare, thus making data collection difcult over long periods. We hope that the study adds information, with so many patients followed closely for 15 years. From the present ndings we recommend that PCNL, although invasive, is a successful and durable means of managing CDS. For patients who are unwilling or unable to undergo an invasive intervention, ESWL provides acceptable symptomatic improvement, despite low stone-free rates, with reasonably low recurrence rates. URS is a successful salvage procedure for anteriorly located middle or upper pole small CDS. A possible criticism is the long study period of 15 years, in which there might have been changes in treatment policy. However, in our centre the management was supervised by the same consultants so the policy on treatment decisions was not changed signicantly over this period. Also, little is known about the long-term risk of stone recurrence or stone growth after minimally invasive treatments for CDS. Our main aim was to determine the long-term outcome rather than comparing the two techniques. After counselling the patients on the options available, our current treatment algorithm for a stone-bearing calyceal diverticulum is as follows. Given that the stone is <1 cm and the diverticulum neck is radiographically patent, and if the patient is seeking a noninvasive outpatient treatment, then lithotripsy is used as a primary treatment. Failed ESWL, large stones (>1 cm), multiple stones, and a narrow diverticular neck are the main indications for percutaneous treatment. URS is typically used as a secondary procedure after any failed primary treatment (ESWL or PCNL) for small residual stones in the middle or upper pole. In conclusion, PCNL is an effective and durable means of treating CDS, regardless of stone size or location of the diverticulum. However, ESWL is an acceptable alternative treatment in selected patients (stone size <1 cm and with a patent diverticular neck), as

despite lower stone-free rates, most patients are rendered symptom-free with minimal complications, and remain so in the long term. The long-term recurrence rates (8% for ESWL and 11% for PCNL) are similar. Although it would be very difcult to recruit signicantly many patients with CDS in one institution over a reasonable period, our conclusions should be validated in a prospective study.

11

12

CONFLICT OF INTEREST 13 None declared.

REFERENCES 14 Devine CJ Jr, Guzman JA, Devine PC, Poutasse EF. Calyceal diverticulum. J Urol 1969; 101: 811 2 Timmons JW Jr, Malek RS, Hattery RR, DeWeerd JH. Caliceal diverticulum. J Urol 1975; 114: 69 3 Middleton AW Jr, Pster RC. Stonecontaining pyelocaliceal diverticulum: embryogenic, anatomic, radiologic and clinical characteristics. J Urol 1974; 111: 26 4 Psihramis KE, Dretler SP. Extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy of caliceal diverticula calculi. J Urol 1987; 138: 707 11 5 Ritchie AW, Parr NJ, Moussa SA, Tolley DA. Lithotripsy for calculi in caliceal diverticula? Br J Urol 1990; 66: 68 6 Streem SB, Yost A. Treatment of caliceal diverticular calculi with extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy: patient selection and extended followup. J Urol 1992; 148: 10436 7 Wulfsohn MA. Pyelocaliceal diverticula. J Urol 1980; 123: 18 8 Hulbert JC, Reddy PK, Hunter DW, Castaneda-Zuniga W, Amplatz K, Lange PH. Percutaneous techniques for the management of caliceal diverticula containing calculi. J Urol 1986; 135: 225 7 9 Jones JA, Lingeman JE, Steidle CP. The roles of extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy and percutaneous nephrostolithotomy in the management of pyelocaliceal diverticula. J Urol 1991; 146: 7247 10 Hendrikx AJ, Bierkens AF, Bos R, Oosterhof GO, Debruyne FM. Treatment of stones in caliceal diverticula: extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy 1

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

versus percutaneous nephrolitholapaxy. Br J Urol 1992; 70: 47882 Ellis JH, Patterson SK, Sonda LP, Platt JF, Sheffner SE, Woolsey EJ. Stones and infection in renal caliceal diverticula: treatment with percutaneous procedures. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1991; 156: 995 1000 Monga M, Smith R, Ferral H, Thomas R. Percutaneous ablation of caliceal diverticulum: long-term followup. J Urol 2000; 163: 2832 Shalhav AL, Soble JJ, Nakada SY, Wolf JS Jr, McClennan BL, Clayman RV. Long-term outcome of caliceal diverticula following percutaneous endosurgical management. J Urol 1998; 160: 16359 Landry JL, Colombel M, Rouviere O et al. Long term results of percutaneous treatment of caliceal diverticular calculi. Eur Urol 2002; 41: 4747 Auge BK, Munver R, Kourambas J, Newman GE, Wu NZ, Preminger GM. Neoinfundibulotomy for the management of symptomatic caliceal diverticula. J Urol 2002; 167: 161620 Kim SC, Kuo RL, Tinmouth WW, Watkins S, Lingeman JE. Percutaneous nephrolithotomy for caliceal diveticular calculi: a novel single stage approach. J Urol 2005; 173: 11948 Skolarikos A, Alivizatos G, de la Rosette J. Extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy 25 years later: complications and their prevention. Eur Urol 2006; 50: 98190 Jackman SV, Hedican SP, Peters CA, Docimo SG. Percutaneous nephrolithotomy in infants and preschool children: experience with a new technique. Urology 1998; 52: 697701 Liatsikos EN, Bernardo NO, Dinlenc CZ, Kapoor R, Smith AD. Caliceal diverticular calculi: is there a role for metabolic evaluation? J Urol 2000; 164: 1820 Auge BK, Maloney ME, Mathias BJ, Pietrow PK, Preminger GM. Metabolic abnormalities associated with calyceal diverticular stones. BJU Int 2006; 97: 10536 Auge BK, Munver R, Kourambas J, Newman GE, Preminger GM. Endoscopic management of symptomatic caliceal diverticula: a retrospective comparison of percutaneous nephrolithotripsy and ureteroscopy. J Endourol 2002; 16: 55763 Batter SJ, Dretler SP. Ureterorenoscopic approach to the symptomatic caliceal diverticulum. J Urol 1997; 158: 70913 Miller SD, Ng CS, Streem SB, Gill IS.

2 0 07 T H E A U T H O R S

JOURNAL COMPILATION

2 0 07 B J U I N T E R N AT I O N A L

155

T U R N A ET AL.

Laparoscopic management of caliceal diverticular calculi. J Urol 2002; 167: 124852 24 Ramakumar S, Gaston KE, Fabrizio MD et al. Laparoscopic management of calyceal diverticula: a multi-institutional study. J Urol 2002; 167: 18 (abstract) 25 Wong C, Zimmerman RA. Laparoscopy-

assisted transperitoneal percutaneous nephrolithotomy for renal caliceal diverticular calculi. J Endourol 2005; 19: 60813 Correspondence: Burak Turna, Section of Laparoscopic and Robotic Surgery, Glickman Urological Institute, Cleveland Clinic

Foundation, 9500 Euclid Avenue, Cleveland, OH 44195, USA. e-mail: burakturna@gmail.com Abbreviations: PCNL, percutaneous nephrolithotomy; URS, ureterorenoscopy/ ureterorenoscopic management; CDS, calyceal diverticular stone(s).

156

JOURNAL COMPILATION

2 0 07 T H E A U T H O R S

2 0 07 B J U I N T E R N AT I O N A L

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (121)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (588)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (400)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (266)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5794)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (345)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (895)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (74)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- NDA For Consultants Template-1Dokumen4 halamanNDA For Consultants Template-1David Jay Mor100% (1)

- Measurement System AnalysisDokumen42 halamanMeasurement System Analysisazadsingh1Belum ada peringkat

- Facility Management SystemDokumen6 halamanFacility Management Systemshah007zaad100% (1)

- Medik8 - HyperpigmentationDokumen8 halamanMedik8 - HyperpigmentationMustika Dwi SusilowatiBelum ada peringkat

- Position PaperDokumen9 halamanPosition PaperRoel PalmairaBelum ada peringkat

- Trigger: Business Process Procedure OverviewDokumen11 halamanTrigger: Business Process Procedure Overviewcalalitbajaj100% (1)

- InvitationDokumen1 halamanInvitationMustika Dwi SusilowatiBelum ada peringkat

- Upso Search ResultsDokumen5 halamanUpso Search ResultsMustika Dwi SusilowatiBelum ada peringkat

- Chika Novani: Buying On CreditDokumen3 halamanChika Novani: Buying On CreditMustika Dwi SusilowatiBelum ada peringkat

- A Retrieved Reformation SummaryDokumen2 halamanA Retrieved Reformation SummaryMustika Dwi Susilowati100% (1)

- ASEAN Foreign Ministers Call For Self-Restraint in S.China Sea DisputeDokumen2 halamanASEAN Foreign Ministers Call For Self-Restraint in S.China Sea DisputeMustika Dwi SusilowatiBelum ada peringkat

- ADM CardioAid SDokumen2 halamanADM CardioAid SMustika Dwi SusilowatiBelum ada peringkat

- Summary of Product Characteristics: 4.1 Therapeutic IndicationsDokumen6 halamanSummary of Product Characteristics: 4.1 Therapeutic IndicationsMustika Dwi SusilowatiBelum ada peringkat

- 25200931Dokumen7 halaman25200931Mustika Dwi SusilowatiBelum ada peringkat

- Raport de Incercare TL 82 Engleza 2015 MasticDokumen3 halamanRaport de Incercare TL 82 Engleza 2015 MasticRoxana IoanaBelum ada peringkat

- 556pm 42.epra Journals-5691Dokumen4 halaman556pm 42.epra Journals-5691Nabila AyeshaBelum ada peringkat

- Analisa SWOT Manajemen Pendidikan Di SMK Maarif 1 KebumenDokumen29 halamanAnalisa SWOT Manajemen Pendidikan Di SMK Maarif 1 Kebumenahmad prayogaBelum ada peringkat

- General Director AdDokumen1 halamanGeneral Director Adapi-690640369Belum ada peringkat

- RH S65A SSVR Users ManualDokumen11 halamanRH S65A SSVR Users ManualMohd Fauzi YusohBelum ada peringkat

- DPS Ibak en PDFDokumen9 halamanDPS Ibak en PDFjsenadBelum ada peringkat

- MGT 3399: AI and Business Transformati ON: Dr. Islam AliDokumen26 halamanMGT 3399: AI and Business Transformati ON: Dr. Islam AliaymanmabdelsalamBelum ada peringkat

- Cma Inter GR 1 Financial Accounting Ebook June 2021 OnwardsDokumen358 halamanCma Inter GR 1 Financial Accounting Ebook June 2021 OnwardsSarath KumarBelum ada peringkat

- AMC Mining Brochure (A4 LR)Dokumen2 halamanAMC Mining Brochure (A4 LR)Bandung WestBelum ada peringkat

- VM PDFDokumen4 halamanVM PDFTembre Rueda RaúlBelum ada peringkat

- Caso 1 - Tunel Sismico BoluDokumen4 halamanCaso 1 - Tunel Sismico BoluCarlos Catalán CórdovaBelum ada peringkat

- Class Assignment 2Dokumen3 halamanClass Assignment 2fathiahBelum ada peringkat

- Feasibility QuestionnaireDokumen1 halamanFeasibility QuestionnaireIvy Rose Torres100% (1)

- BR186 - Design Pr¡nciples For Smoke Ventilation in Enclosed Shopping CentresDokumen40 halamanBR186 - Design Pr¡nciples For Smoke Ventilation in Enclosed Shopping CentresTrung VanBelum ada peringkat

- Wind Flow ProfileDokumen5 halamanWind Flow ProfileAhamed HussanBelum ada peringkat

- C++ & Object Oriented Programming: Dr. Alekha Kumar MishraDokumen23 halamanC++ & Object Oriented Programming: Dr. Alekha Kumar MishraPriyanshu Kumar KeshriBelum ada peringkat

- 99990353-Wsi4-2 C1D2-7940022562 7950022563 7940022564Dokumen2 halaman99990353-Wsi4-2 C1D2-7940022562 7950022563 7940022564alltheloveintheworldBelum ada peringkat

- Brief On Safety Oct 10Dokumen28 halamanBrief On Safety Oct 10Srinivas EnamandramBelum ada peringkat

- Feed Water Heater ValvesDokumen4 halamanFeed Water Heater ValvesMukesh AggarwalBelum ada peringkat

- ScriptDokumen7 halamanScriptAllen Delacruz100% (1)

- Ar 2011Dokumen36 halamanAr 2011Micheal J JacsonBelum ada peringkat

- Enhancing LAN Using CryptographyDokumen2 halamanEnhancing LAN Using CryptographyMonim Moni100% (1)

- Report - Summary - Group 3 - MKT201Dokumen4 halamanReport - Summary - Group 3 - MKT201Long Nguyễn HảiBelum ada peringkat

- C.F.A.S. Hba1C: English System InformationDokumen2 halamanC.F.A.S. Hba1C: English System InformationtechlabBelum ada peringkat

- Installing Oracle Fail SafeDokumen14 halamanInstalling Oracle Fail SafeSantiago ArgibayBelum ada peringkat