Rehiring Temporary Workers

Diunggah oleh

Eumell Alexis PaleHak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Rehiring Temporary Workers

Diunggah oleh

Eumell Alexis PaleHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

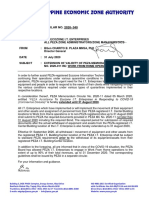

July 23, 2012 Ma. Ces Curameng Human Resources Manager American Power Conversion (A.P.C.) B.V.

Lot 1, Block 5, Phase 2, PEZA, Rosario, Cavite

Dear Madam: This is in response to your query during our meeting last July 18, 2012 requesting for my opinion on whether repeated re-hiring of temporary worker may result in risk of having the said employee attain regularization. According to the facts you mentioned in the said meeting, there was a temporary worker that is being repeatedly rehired for various purposes and not based on specific project. In reply to thereto, please be informed that Article 280 of the Labor Code differentiate regular employment, project or seasonal employment, and casual employee. The said Article of the Labor Code provides: The provisions of written agreement to the contrary notwithstanding and regardless of the oral agreement of the parties, an employment shall be deemed to be regular where the employee has been engaged to perform activities which are usually necessary or desirable in the usual business or trade of the employer except where the employment has been fixed for a specific project or undertaking the completion or termination of which has been determined at the time of the engagement of the employee or where the work or service to be performed is seasonal in nature and the employment is for the duration of the season. An employment shall be deemed to be casual if it is not covered by the preceding paragraph: Provided, That any employee who has rendered at least one year of service, whether such service is continuous or broken, shall be considered a regular employee with respect to the activity in which he is employed and his employment shall continue while such activity exists. The Supreme Court in interpreting the provision of the preceding Article of the Labor Code differentiates the three kinds of employment. In Cosmos Bottling Corporation versus NLRC, the Supreme Court provides: The first paragraph provides that regardless of any written or oral agreement to the contrary, an employee is deemed regular where he is engaged in necessary or desirable activities in the usual trade or business of the employer.

A project employee, on the other hand, has been defined to be one whose employment has been fixed for a specific project or undertaking, the completion or termination of which has been determined at the time of the engagement of the employee or where the work or service to be performed is seasonal in nature and the employment is for the duration of the season. The second paragraph of the provision defines casual employees as those who do not fall under the definition of the first paragraph. However, with respect to the first two kinds of employee, the principal test for determining whether an employee is a project employee or a regular employee is whether or not the project employee was assigned to carry out a specific project or undertaking, the duration and scope of which were specified at the time the employee was engaged for that period. In a recent case decided by this Court, the nature of project employment was explained. We noted that in the realm of business and industry, project, could refer to at least two (2) distinguishable types of activities. First, a project could refer to a job or undertaking that is within the regular or usual business of the employer company, but which is distinct and separate, and identifiable as such, from the other undertakings of the company. Such job or undertaking begins and ends at determined or determinable times. Second, a project could also refer to a particular job or undertaking that is not within the regular business of the corporation. Such a job or undertaking must also be identifiably separate and distinct from the ordinary or regular business operations of the employer. The job or undertakings also begins and ends at determined or determinable times. Regardless of whether or not the project is within the regular or usual business of the employer, the requirement is that it should begin and ends at determined or determinable times. Therefore it is important for the Company to determine the exact duration or termination of the project at the time of the engagement and this must be clearly explained to the employee. The duration or termination cannot also be dependent on any conditions (e.g. completion of work or stages of project). Otherwise, the company is at risk of having such a project employee becoming a regular employee. In Violeta versus NLRCc, the Supreme Court ruled as follows: The predetermination of the duration or period of a project employment is important in resolving whether one is a project employee or not. On this score, the term period has been defined to be a length of existence; duration. A point of time marking a termination as a cause or an activity; an end, a limit, a bound; conclusion; termination. A series of years, months or days in which something is completed. A time of definite length or the period from one fixed date to another fixed date. Following the rule on precedents, we once again hold that the respective employment of the present petitioner is not subject to a term but rather to a

condition, that is, progress accomplishment. As we have stated in De Jesus, it cannot be said that their employment has been pre-determined because, firstly, the duration of their work is contingent upon the progress accomplishment and, secondly, the contract gives private respondent the liberty to determine the personnel and the number as the work progresses. It is ineluctably not definite so as to exempt the private respondent from the structures and effects of Article 280. With such ambiguous and obscure word and conditions, petitioners employment was not co-existence with the duration of the their particular work assignments because their employer could, at any stage of such work, determine whether their services were needed or not. Their services could then be terminated even before the completion of the phase of work assigned to them. To be exempted from the presumption of regularity of employment, therefore, the agreement between a project employee and his employer must strictly conform with the requirements and conditions provided in Article 280. It is not enough that an employee is hired for a specific project or phase of work. There must also be a determination of or a clear agreement on the completion or termination of the project at the time the employee is engaged if the objective of Article 280 is to be achieved. Since this requirement was not met in the petitioners case, they should be considered as regular employees despite their admissions and declarations that they are project employees made under the circumstances unclear to us. Also, what is the effect if a project employee was repeatedly rehired continuously (without gap) after the cessation of a project? He may become a regular employee as well. In Tomas Lao versus NLRC, the Supreme Court ruled: While it may be allowed that in the instant case the workers were initially hired for specific projects or undertakings of the Company and hence can be classified as project employees, the repeated re-hiring and the continuing need for their services over a long span of time (the shortest, at seven years) have undeniably made them regular employees. Thus, we held that where the employment of project employee is extended long after the supposed project has been finished, the employees are removed from the scope of the project employees and considered regular employees. While the length of time may not be a controlling test for project employment, it can be a strong factor in determining whether the employee was hired for a specific undertaking or in fact tasked to perform functions which are vital, necessary, and indispensable to the usual business or trade of the employer. IN the case at bar, private respondents had already gone through the status of project employees. But their employments become non-coterminous with specific projects when they are started to be continuously rehired due to the demands of the petitioners business and were re-engaged for many more projects without interruption.

It is clear therefore, that continuously re-hiring the same project employees may result in them becoming regular employees. What about casual employees? The second paragraph provides that if a casual employee has rendered at least one year of service, whether such service is continuous or broken, shall be considered a regular employee with respect to the activity in which he is employed and his employment shall continue while such actually exists. This has been upheld by the Supreme Court in various rulings (Arrastre & Stevedoring versus Boclot/PLDT versus Arceo/De Leon versus NLRC). In PLDT versus Arceo, the Supreme Court ruled as followed: Under the foregoing provision, a regular employee is (1) one who is either engaged to perform activities that are necessary or desirable in the usual trade or business of the employer or (2) a casual employee who has rendered at least one year of service, whether continuous or broken, with respect to the activity in which he is employed. Under the first criterion, respondent is qualified to be a regular employee. Her work, consisting mainly of photocopying documents, sorting out telephone bills and disconnection notices, was certainly necessary or desirable to the business of PLDT. But even if the contrary were true, the uncontested fact is that she rendered service for more than one year as a casual employee. Hence, under the second criterion, she is still eligible to become a regular employee. Petitioners argument that respondents position has been abolished, if indeed true, does not preclude Arceos becoming a regular employee. The order to reinstate her also included the alternative to reinstate her to a position equivalent thereto. Thus, PLDT can still regularize her in an equivalent position. In summary therefore, existing jurisprudence of repeated hiring is well settled. Repeated hiring of the same worker may show that the said employee is performing functions that are usual and necessary to the trade or business of the employer. It is imperative therefore that if the temporary worker mentioned is considered a project employee, there should be specific undertakings and the duration is determined at the time of engagement. The said employee cannot be continuously rehired as well (without gap). On the other hand, if the said employee is considered a casual employee, he or she must be hired for at least one year (even with gap or intermittent) as he or she will be considered regular employee. Further Section 7.A.7 of DOLE DO 18-A prohibits repeated hiring of employees under an employment contract of short duration or under Service Agreement of short duration with the same or different contractors, which circumvents the Labor Code provisions on Security of Tenure. It is to be noted that my opinion is provided based on the information as presented. We may not know all circumstantial facts (e.g., the actual contract of the temporary employee and the history of hiring). Hence my opinion is not a valid substitute for

legal opinion. Although my opinion is based on a very detailed research, nevertheless I may have overlooked certain matters. Finally, my opinion is strictly for internal use only and may not be used in any legal proceeding.

Sincerely yours, Eumell Alexis S. Pale, CIA, CPA, RCA General Ledger Process Manager Schneider Electric IT Logistics Lot 1, Block 5, Phase 2, PEZA, Rosario, Cavite

Originally APCs work week is from Monday to Friday (8am to 5pm) and Saturday (8am to 2pm). Therefore only 5 hours are worked every Saturday. As of the date of this writing, we are aware that the company employs a compressed work week scheme but we are not aware if such was approved by the DOLE.

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5794)

- CTA Case On VAT Zero Rating RequirementsDokumen28 halamanCTA Case On VAT Zero Rating RequirementsEumell Alexis PaleBelum ada peringkat

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- Offficial Position of PEZA On CREATE Bill 27 May 2020Dokumen2 halamanOffficial Position of PEZA On CREATE Bill 27 May 2020Eumell Alexis PaleBelum ada peringkat

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- Second Division: PetitionerDokumen27 halamanSecond Division: PetitionerEumell Alexis PaleBelum ada peringkat

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (895)

- Executive Order No. 55Dokumen3 halamanExecutive Order No. 55Eumell Alexis PaleBelum ada peringkat

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (400)

- RR No. 21-2020 - VAAPDokumen9 halamanRR No. 21-2020 - VAAPJerwin DaveBelum ada peringkat

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- Memorandum Circular - FINAL, Extension of MC 2020-011 (1) 31 Jul 2020Dokumen1 halamanMemorandum Circular - FINAL, Extension of MC 2020-011 (1) 31 Jul 2020Eumell Alexis PaleBelum ada peringkat

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- Memorandum Circular - FINAL, Extension of MC 2020-011 (1) 31 Jul 2020Dokumen1 halamanMemorandum Circular - FINAL, Extension of MC 2020-011 (1) 31 Jul 2020Eumell Alexis PaleBelum ada peringkat

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- IFRS News 07312015Dokumen1 halamanIFRS News 07312015Eumell Alexis PaleBelum ada peringkat

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (588)

- SPDF - RMC 26-08 Interim Transfer Pricing GuidelinesDokumen1 halamanSPDF - RMC 26-08 Interim Transfer Pricing GuidelinesEumell Alexis PaleBelum ada peringkat

- RMC No. 10-2020 Annex A - Sworn DeclarationDokumen2 halamanRMC No. 10-2020 Annex A - Sworn DeclarationrycasiquinBelum ada peringkat

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- Work-Life For MillennialsDokumen3 halamanWork-Life For MillennialsEumell Alexis PaleBelum ada peringkat

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (74)

- When Bigger Is Not Always BetterDokumen4 halamanWhen Bigger Is Not Always BetterEumell Alexis PaleBelum ada peringkat

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- RMC No. 47-2020Dokumen3 halamanRMC No. 47-2020Eumell Alexis PaleBelum ada peringkat

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (266)

- Accounting Part 1Dokumen1 halamanAccounting Part 1Eumell Alexis PaleBelum ada peringkat

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (344)

- BDB .Presumption Resting On Another PresumptionDokumen2 halamanBDB .Presumption Resting On Another PresumptionEumell Alexis PaleBelum ada peringkat

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- 47.taxability of Productivity Incentive Bonuses.07.10.08.GACDokumen2 halaman47.taxability of Productivity Incentive Bonuses.07.10.08.GACEumell Alexis PaleBelum ada peringkat

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2259)

- Quiz in Midterm (Trasnfer and Business Tax)Dokumen1 halamanQuiz in Midterm (Trasnfer and Business Tax)Eumell Alexis PaleBelum ada peringkat

- Preliminary Exam FIN 2 - SampleDokumen3 halamanPreliminary Exam FIN 2 - SampleEumell Alexis PaleBelum ada peringkat

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- 09.BM - Knowing Your Local Business Tax Concerns.10!11!07.JLADokumen3 halaman09.BM - Knowing Your Local Business Tax Concerns.10!11!07.JLAEumell Alexis PaleBelum ada peringkat

- Umil Vs Ramos 1991Dokumen29 halamanUmil Vs Ramos 1991Rollie AngBelum ada peringkat

- 100 Difficult WordsDokumen3 halaman100 Difficult WordsEumell Alexis PaleBelum ada peringkat

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- PWC Incoterms and IFRSDokumen1 halamanPWC Incoterms and IFRSEumell Alexis Pale0% (1)

- Prado Vs JudgeDokumen7 halamanPrado Vs JudgeFrancis ArvyBelum ada peringkat

- Kilusang Mayon Uno vs. NEDAxDokumen30 halamanKilusang Mayon Uno vs. NEDAxEumell Alexis PaleBelum ada peringkat

- First CasesDokumen9 halamanFirst CasesEumell Alexis PaleBelum ada peringkat

- Stonehill vs. DioknoDokumen13 halamanStonehill vs. DioknoRamon AquinoBelum ada peringkat

- Echegaray Vs Sec of JusticeDokumen8 halamanEchegaray Vs Sec of JusticedesereeravagoBelum ada peringkat

- German vs. Baranganx PDFDokumen43 halamanGerman vs. Baranganx PDFEumell Alexis PaleBelum ada peringkat

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (121)

- Prado Vs JudgeDokumen7 halamanPrado Vs JudgeFrancis ArvyBelum ada peringkat

- People VsDokumen1 halamanPeople VsEumell Alexis PaleBelum ada peringkat

- Osmena v. Orbos DigestDokumen3 halamanOsmena v. Orbos Digestpinkblush717Belum ada peringkat

- Chapter 8 Study Guide and AnswersDokumen3 halamanChapter 8 Study Guide and AnswersbuddylembeckBelum ada peringkat

- Local Business Taxes & Real Property Tax: Atty. Vic C. MamalateoDokumen78 halamanLocal Business Taxes & Real Property Tax: Atty. Vic C. Mamalateoiris7curl100% (1)

- Federico S. Sandoval v. COMELEC, G.R. No. 133842, Jan. 26, 2000Dokumen10 halamanFederico S. Sandoval v. COMELEC, G.R. No. 133842, Jan. 26, 2000Romeo MeguBelum ada peringkat

- Indian PolityDokumen79 halamanIndian Polityvinayks75Belum ada peringkat

- Notes in Statcon - 2019Dokumen5 halamanNotes in Statcon - 2019AJ DimaocorBelum ada peringkat

- Citizenship - For WbcsDokumen6 halamanCitizenship - For WbcsKrishnendu BhattacherjeeBelum ada peringkat

- Land Titles and Deeds Outline 2012.0516Dokumen10 halamanLand Titles and Deeds Outline 2012.0516keith105Belum ada peringkat

- 157 Bulacan V CADokumen2 halaman157 Bulacan V CAFrancisJosefTomotorgoGoingoBelum ada peringkat

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)

- A Rothschild Plan For World GovernmentDokumen6 halamanA Rothschild Plan For World GovernmentJason LambBelum ada peringkat

- Bennett Coleman Vs Union of IndiaDokumen3 halamanBennett Coleman Vs Union of Indiagourdev6Belum ada peringkat

- Punjab Non Gazetted Civil Services Pay Revisions Rules 1972 PDFDokumen134 halamanPunjab Non Gazetted Civil Services Pay Revisions Rules 1972 PDFMalik MajidBelum ada peringkat

- Piadeco's Ownership of San Pedro EstateDokumen8 halamanPiadeco's Ownership of San Pedro Estatefred_41361636100% (3)

- David Dyzenhaus (Ed.) - Law As Politics. Carl Schmitt's Critique of Liberalism PDFDokumen333 halamanDavid Dyzenhaus (Ed.) - Law As Politics. Carl Schmitt's Critique of Liberalism PDFJorge100% (1)

- Appellee's Brief RequirementsDokumen2 halamanAppellee's Brief RequirementsIge OrtegaBelum ada peringkat

- CREW: DOJ: Amicus Brief in Support of Sen. John Edward's Motion To Dismiss Indictment: 9/21/2011 - Proposed Amicus Brief (ECF)Dokumen28 halamanCREW: DOJ: Amicus Brief in Support of Sen. John Edward's Motion To Dismiss Indictment: 9/21/2011 - Proposed Amicus Brief (ECF)CREWBelum ada peringkat

- PNB v. CIRDokumen1 halamanPNB v. CIRJilliane OriaBelum ada peringkat

- Bagtas v. Santos G.R. No. 166682 November 27 2009Dokumen1 halamanBagtas v. Santos G.R. No. 166682 November 27 2009JaylordPataotaoBelum ada peringkat

- Sandiganbayan JurisdictionDokumen2 halamanSandiganbayan JurisdictionGin FranciscoBelum ada peringkat

- St. Vincent Perez v. LPG Refillers Association of The Phils G.R. No. 159149 August 28, 2007Dokumen3 halamanSt. Vincent Perez v. LPG Refillers Association of The Phils G.R. No. 159149 August 28, 2007jon_cpaBelum ada peringkat

- FedralisDokumen13 halamanFedralisnicealipkBelum ada peringkat

- Severe EmailsDokumen3 halamanSevere EmailsRob PortBelum ada peringkat

- Pol Science NotesDokumen56 halamanPol Science NotesMia SamBelum ada peringkat

- Final Book-ReviewDokumen34 halamanFinal Book-ReviewJoshua Vergara CortelBelum ada peringkat

- 1 StayDokumen22 halaman1 StayDavid Oscar Markus100% (1)

- 25 RP Vs Heirs of Borbon PDFDokumen4 halaman25 RP Vs Heirs of Borbon PDFKJPL_1987Belum ada peringkat

- Tavora v. GavinaDokumen8 halamanTavora v. Gavinaanxhei26Belum ada peringkat

- First Amendment LawsuitDokumen11 halamanFirst Amendment LawsuitKGW NewsBelum ada peringkat

- Democracy EssayDokumen2 halamanDemocracy EssayAlexandra RaduBelum ada peringkat

- Skelly Protocol - Final.09.05.18Dokumen6 halamanSkelly Protocol - Final.09.05.18kateBelum ada peringkat

- Goal Setting: How to Create an Action Plan and Achieve Your GoalsDari EverandGoal Setting: How to Create an Action Plan and Achieve Your GoalsPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (9)

- Scaling Up: How a Few Companies Make It...and Why the Rest Don't, Rockefeller Habits 2.0Dari EverandScaling Up: How a Few Companies Make It...and Why the Rest Don't, Rockefeller Habits 2.0Penilaian: 5 dari 5 bintang5/5 (1)

- The Five Dysfunctions of a Team SummaryDari EverandThe Five Dysfunctions of a Team SummaryPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (59)

- The Power of People Skills: How to Eliminate 90% of Your HR Problems and Dramatically Increase Team and Company Morale and PerformanceDari EverandThe Power of People Skills: How to Eliminate 90% of Your HR Problems and Dramatically Increase Team and Company Morale and PerformancePenilaian: 5 dari 5 bintang5/5 (22)

- Working with AI: Real Stories of Human-Machine Collaboration (Management on the Cutting Edge)Dari EverandWorking with AI: Real Stories of Human-Machine Collaboration (Management on the Cutting Edge)Penilaian: 5 dari 5 bintang5/5 (5)

- The 5 Languages of Appreciation in the Workplace: Empowering Organizations by Encouraging PeopleDari EverandThe 5 Languages of Appreciation in the Workplace: Empowering Organizations by Encouraging PeoplePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (46)

- The Fearless Organization: Creating Psychological Safety in the Workplace for Learning, Innovation, and GrowthDari EverandThe Fearless Organization: Creating Psychological Safety in the Workplace for Learning, Innovation, and GrowthPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (101)

- 12 Habits Of Valuable Employees: Your Roadmap to an Amazing CareerDari Everand12 Habits Of Valuable Employees: Your Roadmap to an Amazing CareerBelum ada peringkat

- Crucial Conversations Tools for Talking When Stakes Are High, Second EditionDari EverandCrucial Conversations Tools for Talking When Stakes Are High, Second EditionPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (432)