Health Care Outcomes in Nordic Countries vs. Health Care Outcomes in The United States: An Objective Analysis

Diunggah oleh

paradiselsewhereJudul Asli

Hak Cipta

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Health Care Outcomes in Nordic Countries vs. Health Care Outcomes in The United States: An Objective Analysis

Diunggah oleh

paradiselsewhereHak Cipta:

Health Care Outcomes in Nordic Countries vs.

Health Care Outcomes in the United States: An Objective Analysis

Kyle Rogowski SOCI 370 Health and Illness Siena College Dr. Matcha April 19, 2013

ABSTRACT It was not long ago that the United States was situated atop the world in the health care arena. However, their international standing in the area of medicine has been declining for decades. The Nordic countries, namely Sweden, Norway, Denmark, and Finland, have been ascending to the top of the rankings during this same time period. These countries are renowned for offering universal health services to their citizens and having some of the best care in the world overall. Why are health care outcomes commonly higher in the Nordic countries than in the United States? This study examines the structure and finance of health systems, and indicators of health within Nordic countries as well as within the United States. Findings show that countries that employ a universal health system generally assign less funding to this sector annually while simultaneously experiencing better health outcomes and less inequality.

INTRODUCTION This research-based analysis compares the health care systems of the United States to four Nordic countries: Sweden, Norway, Denmark, and Finland. Ninety-nine percent of the Nordic population is comprised from these four countries which makes them the best candidates for examination. The health care system of the United States is currently undergoing drastic changes, but it is still generally considered to be lacking in several areas. In 2011, there were still forty-nine million people without health care coverage in the United States (DeNavas-Walt, Proctor & Smith, 2012). On the other hand, the Nordic countries are widely believed to possess some of the best health care available in the world. Why are health care outcomes commonly higher in the Nordic countries than in the United States? The Nordic Model of health care systems is understood to reflect tax-based funding, publicly owned and operated hospitals, and universal access. Magnussen, Vrangbaek and Saltman (2009) identify core features of health care systems that are consistent within all Nordic countries. Two foundational goals that characterize Nordic health care systems are equity and participation. Equity implies a health care sector where the benefits of care are equal for all individuals. Participation refers to the tradition of sending most policy documents out to a hearing where peoples voices could be heard rather than adopting the policy through the government. Although governance implies decisions are made in principle through public interest, direct participation is

of high importance in Nordic countries and is strongly valued (Magnussen et al., 2009). Albeit commonalities between systems within the Nordic countries do exist, there are considerable variations in structure, policy, and outcomes that will be thoroughly examined.

SWEDEN Structure of Health Care System Health care [in Sweden] is mainly provided publicly and financed out of tax revenue or social insurance contributions (Marchand & Schroyen, 2005:1-2). There also exists a private health care sector. More than two-thirds of Swedens health care costs are financed by direct taxes (Honekamp & Possenriede, 2008). Three basic principles apply to the Swedish health care system. Human dignity is the first principle; this means that all people have an equal right to dignity, and they should all have the same rights, regardless of class status. Every resident of Sweden receives health care, regardless of nationality. Need and solidarity make up the second principle; this holds that citizens with the greatest needs take precedence in medical care. The third principle is costeffectiveness, meaning that when a choice must be made between health care options, there should be a reasonable connection between costs and effects. This connection is measured in terms of improved health and improved quality of life (Anell, Glenngard & Merkur, 2012). In 1982, Sweden passed the Health and Medical Services Act,

which specifies that the responsibility for securing health care for everybody living in the country lies within the county councils and municipalities. Primary care forms the foundation of Swedens health care system. Services for conditions that require extensive treatment in hospitals are provided at regional hospitals (Anell et al., 2012). Costs The Swedish health care system is primarily funded through taxes. Both county councils and municipalities impose income taxes on their respective populations. There are also direct user charges for primary and specialized care. In 2009, Swedish county councils accrued roughly $894 million in patients fees and other fees; this figure accounted for 2.4% of the councils total revenues. The county councils set their own levels of user charges for primary and specialist care. In nearly all county councils, children and people under twenty years of age are excused from any patient fees. Sweden has also imposed a national out-of-pocket payment ceiling; individuals are exempt from any further charges for the remainder of the twelve-month period that started with the patients first visit to a physician if they have reached the ceiling (Anell et al., 2012). Financing On average, health funding in Sweden increased by 3.9% per year between 2000 and 2009. The increase in expenditures throughout this decade was more due to a decrease in Gross Domestic Product rather

than an increase in funding (Anell et al., 2012). In order to consolidate financial resources following the global recession, however, the growth rate in spending slowed down to two percent in 2010, as was the case with most OECD countries. Eighty-one percent of health spending in Sweden was funded by public sources in 2010, well above the average of seventy-two percent in OECD (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development) countries. The public sector is the main source of health care funding, but seventeen percent of expenditures on health in 2010 were private. Total health spending in this year accounted for 9.6% of Swedens GDP, just above the OECD average of 9.5%. Sweden also spends more on health per capita than many OECD countries, with $3,758 in 2010; the average for OECD countries was $3,268 (How Does Sweden Compare, 2012). Life Expectancy Life expectancy in Sweden is among the highest in the world. Women are expected to live until 83.2 years of age, and men are expected to live until 79.1 years of age. Over the past three decades, the average life expectancy has risen by 5.5 years. Sweden currently has one of the worlds oldest populations (Anell et al., 2012). This could be due in part to the aging of the baby boomer generation, but having such an elderly population speaks volumes to the quality of health care in Sweden. Infant Mortality Sweden has one of the lowest infant mortality rates in the world. From 2005 to 2010, Sweden averaged only three infant deaths

per one thousand live births, placing it behind only Singapore, China, Iceland, and Luxembourg (World Population Prospects, 2011). All pregnant women in the country are offered regular health checks, screenings, psychological support, and education throughout their pregnancies and nearly all women participate in the program (Anell et al., 2012). Other Variables and Indicators of Health Sweden places a huge emphasis on strengthening and supporting parents in their parenting role, increasing suicide prevention efforts, promoting healthy eating habits and physical activity, and reducing the use of tobacco. The country also provides social programs designed to prevent accidents and ill health. These programs have largely proved to be successful; deaths due to traffic accidents have been declining drastically since the 1970s. The number of daily smokers has also substantially decreased during this time. Sweden is lower than any other European country in the proportion of daily smokers among men. Reduction in the use of tobacco could be attributed to a tax increase on tobacco products and the introduction of non-smoking campaigns (Anell et al., 2012).

NORWAY Structure of Health Care System There are three levels of organization in the Norwegian health care system: national, regional, and local. Overall responsibility for the health care sector falls into the hands of those at the

national level. The regional level is run by five regional health organizations which handle specialist care, and the local level takes responsibility for primary health care. The countrys health care system is primarily funded through taxes. Norwegian municipalities maintain the right to levy income taxes on their respective populations, but regional health authorities gather funds through transfers from the national government. Each municipality must decide how to best serve its citizens with primary care, which is mainly publicly provided. General practitioners in Norway are self-employed, but financed by the social insurance system, municipalities, and patients out-of-pocket expenses. Other health care professionals are mainly salaried due to public ownership of health care providers. Recent national reforms to the health care system have targeted three areas: responsibility for providing medical care services, priorities and patients rights, and cost containment. The main strengths of the Norwegian health care system are access to health care for all individuals regardless of income, local and regional accountability, and public and political interest in improving medical care (Johnsen, 2006). Costs Taxes are the primary financier of Norways health care system. The national government also sets user charges for its citizens. A simple consultation with ones primary care physician could cost a patient between $20 and $35. Specialist and ambulatory care typically only costs around $45. Co-pays and other simple user

charges are the only costs a patient seeking medical care in Norway will be faced with (Johnsen, 2006). User charges for health care services: January 2006 Type of Cost Ceilings NKr Physician Consultations 125 (day), 210 (night) Sick Call to Physician 150 (day), 235 (night) Specialist/Ambulatory Care 265 Query/Advice 35 Laboratory Tests 47 X-rays 200 Ordinary Charge for Psychologist 265 1.5 Hours with Psychologist 397 2 Hours with Psychologist 530 2.5 Hours with Psychologist 662 3 Hours with Psychologist 795 Purchasing of Pharmaceuticals 36% of the value of the prescription, but <500 NKr per prescription *1 Norwegian Krone = 0.17 USD Source: Johnsen, Jan R. 2006. Health Systems in Transition: Norway. European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, 8(1): 1-158. Financing Norway spends the second most per capita on health care out of all OECD countries; the only country that spends more per capita is the United States. Norway, which spent $5,388 per capita on health care in 2010, is well above the OECD average of $3,268. Between 2000 and 2009, Norways health spending per capita increased by 3.7% annually. However, the total health spending of Norway in 2010 was just 9.4% of GDP. This places Norway right below the OECD average of 9.5% (How Does Norway Compare, 2012). In other words, Norway can afford to spend so much on health care per capita due to their high GDP with purchasing power parity taken into consideration, and their relatively low population; a July 2013 estimate from the World Factbook places them 120th on the world population list with about

4.72 million residents (CIA, 2013). A 2012 estimate of GDP-PPP from the World Factbook puts them in 47th place in the world with $278 billion (CIA, 2013). As is the case with most OECD countries, the public sector is the main source of funding for Norways health care system. In 2010, 85.5% of health spending was funded by public sources, which puts Norway well above the OECD average of 72.2% (How Does Norway Compare, 2012). Life Expectancy The life expectancy for Norwegian residents in 2010 was 81.2, more than a year over the OECD average of 79.8. Norway has enjoyed a drastic increase in life expectancy over the past decades due in part to improvement in living conditions and advancements in medical technology (How Does Norway Compare, 2012). Diseases of the circulatory system are still the leading cause of death in Norway, but progress in health care has notably decreased the amount of deaths attributed to these diseases, which helps to account for the longer life expectancy the country is experiencing today (Johnsen, 2006). Infant Mortality Norways infant mortality rate has been severely decreasing over the past six decades, going from twenty-two deaths per one thousand live births in 1950 to only three in 2010. This places Norway comfortably behind only seven United Nations countries relative to this aspect of health (World Population Prospects, 2011). Norwegian municipalities are left in charge of preventive and

curative treatments, which include routine medical check-ups during pregnancy and after birth. The Medical Birth Registry of Norway provides research and surveillance of health conditions regarding pregnancy (Johnsen, 2006). Other Variables and Indicators of Health Over the past thirty years, the number of adults who smoke in Norway has drastically declined due in part to anti-smoking campaigns, advertisement bans, and increased taxation on tobacco products. In 1980, thirty-six percent of adults in Norway smoked daily, while that number had decreased to nineteen percent in 2010, two percentage points below the OECD average. The proportion of Norways population that is obese is also below the OECD average. Based on self-reported height and weight, in 2008, it was determined that ten percent of Norways citizens were obese. This number could seem high, but when the OECD average of fifteen percent is taken into consideration, it is apparent that Norway is ahead of the curve; obesity leads to increased disease prevalence, and ultimately higher health care costs (How Does Norway Compare, 2012). Norway also has the lowest rate of mortality due to traffic accidents in the world. This could be explained by frequent road sobriety checks and a low drink-drive limit (Johnsen, 2006).

DENMARK Structure of Health Care System Denmark is a parliamentary democracy with three levels of control: the state, regions, and municipalities. Traditionally, the country has had a decentralized health care system. However, due to recent policy changes, the system has gradually become more centralized in several ways. The structural reforms of 2007 merged counties and municipalities into fewer larger regions of control, and hospitals have been becoming fewer, bigger, and more specialized. The number of regions decreased from 14 to 5, and municipalities from 275 to 98, essentially re-centralizing medical care. The Danish Healthcare Quality Programme has also established a nationwide accreditation system which sets standards for the countrys health system providers. Viewing Denmark through an international sociological lens, the country could be characterized as being relatively healthy. However, when the other Nordic countries are taken into account, Denmark lags behind in several health areas. The primary sector of health care consists of selfemployed practitioners and municipal health services. General practitioners refer patients to hospitals and specialists, which are operated by the regions. Danish health legislation allows the countrys residents equal access to health care and entitles them the choice to select treatment from any hospital in the country (Olejaz et al., 2012).

Costs Historically, hospital care and pharmaceutical treatment has been provided free of charge. Some services that are provided outside of hospitals are paid for by the patient, while some services are covered by the region or municipality. Majority votes in parliament determine which services are subsidized and by how much. There has not been a national out-of-pocket charges policy, and the size of many user charges is independent of the patients income (Olejaz et al., 2012). Financing In 2010, health spending in Denmark accounted for 11.1% of GDP, which placed them well above the OECD average of 9.5%. The country was also well above the OECD average in health spending per capita, with $4,464. The only Nordic country that landed higher on this list was Norway. Public sources accounted for 85.1% of health spending in 2010, which was the third highest among all OECD countries. Between 2000 and 2009, Denmark increased their medical care spending by an average of 3.6% annually, but a decrease of 1.6% occurred in 2010 to help make up for the effects of the global recession(How Does Denmark Compare, 2012). The following graph examines the percentage of GDP spent on health care from 1995 to 2008 for the three Nordic countries that have been examined thus far. As is evident, the structural changes that Denmark underwent in 2007 led to an increase in health spending, and as we now know, that trend continued upward.

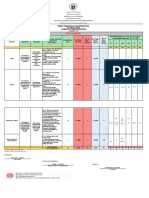

Trends in Health Expenditure as a Percentage of GDP

Source: Olejaz, Maria. 2012. Denmark: Health System Review. Health Systems in Transition, 14(2): 1-190. Life Expectancy Average life expectancy in Denmark has shown marked increase over time, but the country still lags behind most of its Nordic and Western European counterparts. In 2010, life expectancy at birth stood at 79.3 years, which was half a year less than the OECD average of 79.8 years (How Does Denmark Compare, 2012). There are several reasons that could help to explain the low life expectancy of Danish citizens. A 2000 survey showed that middle-aged women in Denmark had higher mortality rates than other countries in the European Union (Olejaz et al., 2012). Infant Mortality Infant mortality rates in Denmark are among the lowest in Europe. From 2005 to 2010, the country averaged just four deaths per one thousand live births, which places them comfortably in the top

twenty of countries with the lowest rates (World Population Prospects, 2011). A declining infant mortality shows promise for Denmark in future health prospects; it could reflect a reduction in infectious diseases and other serious causes of health issues (Olejaz et al., 2012). Other Variables and Indicators of Health The OECD average of smoking rates among adults sits at 21.1%. In Denmark, the percentage of adults who report smoking daily has more than halved since 1985, from 46.5% to 20% in 2010 (How Does Denmark Compare, 2012). Although the smoking rate in Denmark is below the OECD average, it is still comparatively higher than the other Nordic countries (Olejaz et al., 2012). The obesity rate in Denmark has risen from 9.5% in 2000 to 13.4% in 2010, which is still lower than the OECD average of 15% (How Does Denmark Compare, 2012). Obesity rates continue to climb around the world, which does not bode well for future health care costs, especially in a country such as Denmark where a large percentage of GDP is already allocated to this sector.

FINLAND Structure of Health Care System The Finnish government is divided into three levels: state, province and municipality. Municipalities are autonomous and are held responsible for providing social services for their residents, health services included. According to the countrys constitution,

Everyone shall be guaranteed by an act the right to basic subsistence in the event of unemployment, illness, and disability and during old age as well as at the birth of a child or the loss of a provider. The public authorities shall guarantee for everyone, as provided in more detail by an act, adequate social, health and medical services and promote the health of the population (Vuorenkoski, 2008:xvi). Health care in Finland has arguably been decentralized more than any other European country. However, the government has instituted a program that will restructure municipalities and services in hopes of decreasing the number of municipalities and increase cooperation between them. Every municipality must provide a health center that offers primary health care. Also, Finnish legislation divides the country into twenty hospital districts which are held responsible for providing secondary care for their residents. Several problems with the Finnish health care system have been identified by outsiders. First, there are significant differences that exist between municipalities and the resources they invest in health care which leads to differences in the quality of care offered. Additionally, there are considerable socioeconomic inequalities in the use of health services. Pro-rich inequity in medical care was found to be one of the highest in Finland in 2000. Although mortality rates in the country have fallen, the socioeconomic inequality in mortality appears to be rising (Vuorenkoski, 2008). Costs Municipal health services provide the largest share of care in Finland. These services are financed by municipal taxes, government subsidies, and user charges. Legislation sets maximum user-fees and

an annual ceiling for health care charges. On average, user-fees cover approximately 7% of municipal medical service expenditure. Also, 67% of outpatient pharmaceutical costs on average are reimbursed to the patient. The municipal health care ceiling is considered to be high as compared with other Nordic countries. In cases of extreme poverty or financial struggle, social assistance is available (Vuorenkoski, 2008). Financing Health spending as a percentage of GDP in Finland is lower than all other Nordic countries. In 2010, only 8.9% of GDP was spent on health care. This figure is much lower than the 9.5% average of all OECD countries. Spending per capita in Finland in 2010 fell just below the OECD average. When adjusting for purchasing power parity, the country spent only $3,251 per capita, which also is lower than any other Nordic country. Between 2000 and 2009, Finlands health spending per capita increased an average of 4.3% per year. The public sector is the primary source of medical funding in Finland; 74.5% of spending was funded by public sources in 2010, exceeding the OECD average by 2.3%, yet all of the other Nordic countries are above 80% (How Does Finland Compare, 2012). Life Expectancy In 2010, life expectancy at birth in Finland was 80.2 years, which was approximately half a year higher than the OECD average of 79.8 years (How Does Finland Compare, 2012). Life expectancy has shown a considerable rise in Finland, especially during the last

three decades. Vuorenkoski (2008) attributes the increase to a decline in mortality manageable by health care and an especially drastic decline in mortality related to heart disease. Infant Mortality Finland holds one of the worlds lowest infant mortality rates, at 3 deaths per one thousand live births in 2010. This places them in seventh worldwide for lowest infant mortality (World Population Prospects, 2011). At the beginning of the 1970s, almost fifteen of every one thousand newborns died; since then, though, the rate has been declining rapidly. Finland is renowned for maternal and child health care, pre-dating the introduction of medical centers. Children also receive comprehensive publicly-funded dental care (Vuorenkoski, 2008). Other Variables and Indicators of Health Smoking rates lie at 19% and, although below the OECD average of 21%, are still relatively high. Obesity rates are also exceedingly high; Finlands rate in 2010 was 15.6%, which exceeds the OECD average of 15%, and exceeds that of any other Nordic country (How Does Finland Compare, 2012). Obesity forecasts issues of diabetes and circulatory diseases, but the biggest health issues that Finland faces right now are musculoskeletal diseases, mental health problems, and cancer (Vuorenkoski, 2008).

UNITED STATES Structure of Health Care System At the top of the health care hierarchy in the United States is the federal government. There have been entities and programs that have been assigned to interpret, implement, and ensure conformity to the countrys health system. Some of these entities include the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, the Food and Drug Administration, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. State and local governments also play significant roles in medical care. States have been successful in transcending federal laws for health care policies; for example, Massachusetts was able to commission health insurance for all its citizens in 2006. Funding for the United States health care system is provided by the public sector, the private sector, and the consumer. Public funding sources include the federal government and their policies, such as Medicare and Medicaid, and state and local governments. Private funding includes private health insurance and out-of-pocket payments (Understanding the U.S. Healthcare System, 2010). The United States is one of only three OECD countries where less than half of health spending is publicly financed. Only 48.2% of health expenditure in 2010 was publicly paid for, well below the OECD average of 72.2% (How Does the United States Compare, 2012). The following graph shows the economic breakdown of the financing of the United States health care system.

United States Health Care Expenditure (2010)

Source: Understanding the U.S. Healthcare System. 2010. Retrieved from Jones & Bartlett Publishers website: http://samples.jbpub.com/9780763795405/Chapter1.pdf The United States does not offer universal health care coverage to its residents. There is a significant portion of the countrys population that is left without health insurance. These individuals would have to pay out-of-pocket in order to receive coverage (Understanding the U.S. Healthcare System, 2010). In 2011, 15.7% of the U.S. population was uninsured. This figure was a decrease from the 16.3% that existed in 2010, but in a country with such a large population, 15.7% is approximately 48.6 million people (DeNavas-Walt et al., 2011). If one day some form of basic healthcare coverage is offered to all of the U.S. population, then the United States will become the last Western country to offer universal coverage (Understanding the U.S. Healthcare System, 2010:17).

Costs Costs of health care in the United States are rising. This has resulted in a greater proportion of the costs being passed on to patients in the form of higher premiums and increased deductibles. It has been posed that a more efficient organization of resources in the countrys health care system would allow for preventive care to be offered with little to no increased costs (Understanding the U.S. Healthcare System, 2010). Prices for medical treatment in the United States are much higher than any other country. For example, in 2007, the average price for a set of hospital services for OECD countries was $100. The U.S.s price was over sixty percent higher, with an average of $164 (U.S. Health Care System from an International Perspective, 2012). President Barack Obama signed the PPACA (Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act) into law in 2010. Although the act extends health coverage to millions from select groups that were previously uninsured, it also requires most U.S. residents to purchase a health plan or pay a penalty (Understanding the U.S. Healthcare System, 2010). This could pose financial issues for some people who already suffer economically. Financing Health spending in the United States is 47% higher than it is in any other OECD country. In 2010, 17.6% of the United States GDP was allocated to health care, more than 86% higher than the OECD average of 9.5%. The U.S. also spent $8,233 on health per capita with purchasing power parity adjusted for; this figure was 2.5 times

more than the OECD average of $3,268, and 53% higher than the country that spent the second most per capita. Health spending in the United States increased by an average of 4.3% between 2000 and 2009. Spending is so high in fact, that public spending-which only accounts for 48% of health care expenditures-on health per capita is still greater than in all other OECD countries except for Norway and the Netherlands. Public spending has been increasing more rapidly than private spending since 1990, in part due to expanded coverage (How Does the United States Compare, 2012). Life Expectancy Life expectancy in the United States increased by nearly nine years between 1960 and 2010. This could be attributed to a massive improvement in medical technology, but the OECD average over this same span was eleven years. In 1960, the U.S. life expectancy was 1.5 years above the OECD average; now, it is at 78.7 years, which is more than one year below the average of 79.8 years (How Does the United States Compare, 2012). The United States spends significantly more than any other country on health care services, but this spending does not reflect health outcomes, especially life expectancy. This could be credited to sizeable inefficiencies in the countrys health care system and could reflect poor value of services offered (Understanding the U.S. Healthcare System, 2010). Infant Mortality Between 2005 and 2010, the United States averaged seven deaths per one thousand live births. This number places them just inside

the top fifty in the world (World Population Prospects, 2011). Infant mortality rates have substantially declined in industrialized countries over the past few decades, but for the first time since records have been kept, the United States rate exceeded the OECD median (Understanding the U.S. Healthcare System, 2010). There are severe racial differences in infant mortality rates in the U.S. In 2005, the United States as a whole averaged 6.86 deaths per one thousand live births, but non-Hispanic blacks had a rate of 13.63, 64% higher than any other racial group (MacDorman & Mathews, 2008). Other Variables and Indicators of Health Not only does the United States lag behind other industrialized countries in life expectancy and infant mortality, it lags behind in several other areas as well. Potential years of life lost due to diabetes per one hundred thousand population is 99, which is almost three times as high as the OECD median. The country also has the second highest rate of asthma-related hospital admissions, over two times the OECD median of 52 per one hundred thousand (Understanding the U.S. Healthcare System, 2010), and the highest obesity rates in the world. The OECD average obesity rate in 2010 was 22.2%, whereas the United States rate was 35.9%. Rapidly increasing obesity rates forecasts more health spending for the U.S. in the future, although the country already spends the most by far in this sector. One health indicator that the United States is ahead of the curve in is smoking rate. In 2010, the smoking rate in the U.S. was 15.1%, which

was the third-lowest rate among OECD countries (How Does the United States Compare, 2012).

CONCLUSIONS The United States remains the only industrialized nation in the world that does not offer universal health care to its citizens. Although the country spends over fifty percent more on health care than the next closest nation does, it is not atop the world in any indicators of health categories. On the other hand, the Nordic countries all offer universal health care to their residents and rank among some of the best countries in the world in most health classifications, all while spending much less than the United States. The Nordic Model of health care is largely understood to be one of the best models today. Albeit the health care systems within each Nordic country differ in many ways, they all make up for some socioeconomic inequalities between citizens, and are publicly owned and funded. A Nordic Model is much more effective than the private health insurance system that the United States has implemented; costs are much lower for patients, which leaves them with money in their pockets. This leads to increased spending in the economy, a decrease in the gap between the rich and the poor, and overall better health results for a country. It has been found that public attitudes toward health care gather around historical configuration of health care, but also relate to current economic and demographic variables (Kikuzawa, Olafsdottir & Pescosolido,

2008). The United States has never offered universal medical care to its residents, which could help explain the lack of reform. However, the country has become much more unequal in terms of wealth over time, and changes to make health coverage more available have already been implemented. It remains to be seen how effective the changes in health legislation will be.

REFERENCES Anell, Anders, Anna H. Glenngard, and Sherry Merkur. 2012. Sweden: Health System in Review. Health Systems in Transition, 14(5): 1-144. CIA - The World Factbook. Retrieved April 16, 2013 (https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-worldfactbook/). DeNavas-Walt, Carmen, Bernadette D. Proctor, and Jessica C. Smith. 2011. U.S. Census Bureau - Current Population Reports: Income, Poverty, and Health Insurance Coverage in the United States. U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC, 2012. Honekamp, Ivonne, and Daniel Possenriede. 2008. Redistributive Effects in Public Health Care Financing. The European Journal of Health Economics, 9(4): 405-416. How Does Denmark Compare. 2012. Retrieved from OECD website: http://www.oecd.org/els/healthsystems/BriefingNoteDENMARK2012.pdf How Does Finland Compare. 2012. Retrieved from OECD website: http://www.oecd.org/els/healthsystems/BriefingNoteFINLAND2012.pdf How Does Norway Compare. 2012. Retrieved from OECD website: http://www.oecd.org/els/healthsystems/BriefingNoteNORWAY2012.pdf How Does Sweden Compare. 2012. Retrieved from OECD website: http://www.oecd.org/els/healthsystems/BriefingNoteSWEDEN2012.pdf How Does the United States Compare. 2012. Retrieved from OECD website: http://www.oecd.org/unitedstates/BriefingNoteUSA2012.pdf Johnsen, Jan R. 2006. Health Systems in Transition: Norway. European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, 8(1): 1-158. Kikuzawa, Saeko, Sigrun Olafsdottir, and Bernice A. Pescosolido. 2008. Similar Pressures, Different Contexts: Public Attitudes Toward Government Intervention for Health Care in 21 Nations. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 49(4): 385-399.

MacDorman, Marian F. and T.J. Mathews. 2008. Recent Trends in Infant Mortality in the United States (9). Retrieved from CDC NCHS website: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db09.pdf Magnussen, Jon, Karsten Vrangbaek, and Richard B. Saltman. 2009. Nordic Health Care Systems: Recent Reforms and Current Policy Changes. New York: Open University Press. Marchand, Maurice, and Fred Schroyen. 2005. Can a Mixed Health Care System be Desirable on Equity Grounds?. The Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 107(1): 1-23. Olejaz, Maria, Annegrete Juul Nielsen, Andreas Rudkjobing, Hans Okkels Birk, Allan Krasnik, and Cristina Hernandez-Quevedo. 2012. Denmark: Health System Review. Health Systems in Transition, 14(2): 1-190. U.S. Health Care System From an International Perspective. 2012. Retrieved from OECD website: http://www.oecd.org/els/healthsystems/HealthSpendingInUSA_HealthData2012.pdf Understanding the U.S. Healthcare System. 2010. Retrieved from Jones & Bartlett Publishers website: http://samples.jbpub.com/9780763795405/Chapter1.pdf Vuorenkoski, Lauri. 2008. Finland: Health System in Review. Health Systems in Transition, 10(4): 1-156. World Population Prospects (F06-1). 2011. Retrieved from United Nations website: http://esa.un.org/unpd/wpp/ExcelData/mortality.htm

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (895)

- A SURVEY OF ENVIRONMENTAL REQUIREMENTS FOR THE MIDGE (Diptera: Tendipedidae)Dokumen15 halamanA SURVEY OF ENVIRONMENTAL REQUIREMENTS FOR THE MIDGE (Diptera: Tendipedidae)Batuhan ElçinBelum ada peringkat

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- IMC - BisleriDokumen8 halamanIMC - BisleriVineetaBelum ada peringkat

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- 1"a Study On Employee Retention in Amara Raja Power Systems LTDDokumen81 halaman1"a Study On Employee Retention in Amara Raja Power Systems LTDJerome Samuel100% (1)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5794)

- Timetable - Alton - London Timetable May 2019 PDFDokumen35 halamanTimetable - Alton - London Timetable May 2019 PDFNicholas TuanBelum ada peringkat

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- WinCC Control CenterDokumen300 halamanWinCC Control Centerwww.otomasyonegitimi.comBelum ada peringkat

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (266)

- Revised Final Quarter 1 Tos-Rbt-Sy-2022-2023 Tle-Cookery 10Dokumen6 halamanRevised Final Quarter 1 Tos-Rbt-Sy-2022-2023 Tle-Cookery 10May Ann GuintoBelum ada peringkat

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (400)

- Footing - f1 - f2 - Da RC StructureDokumen42 halamanFooting - f1 - f2 - Da RC StructureFrederickV.VelascoBelum ada peringkat

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- Functions: Var S AddDokumen13 halamanFunctions: Var S AddRevati MenghaniBelum ada peringkat

- BioremediationDokumen21 halamanBioremediationagung24864Belum ada peringkat

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- Monitor Stryker 26 PLGDokumen28 halamanMonitor Stryker 26 PLGBrandon MendozaBelum ada peringkat

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (588)

- Stewart, Mary - The Little BroomstickDokumen159 halamanStewart, Mary - The Little BroomstickYunon100% (1)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- Oral ComDokumen2 halamanOral ComChristian OwlzBelum ada peringkat

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- Jurnal Ekologi TerestrialDokumen6 halamanJurnal Ekologi TerestrialFARIS VERLIANSYAHBelum ada peringkat

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (74)

- Pt. Trijaya Agro FoodsDokumen18 halamanPt. Trijaya Agro FoodsJie MaBelum ada peringkat

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (345)

- Elastomeric Impression MaterialsDokumen6 halamanElastomeric Impression MaterialsMarlene CasayuranBelum ada peringkat

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- Daikin FUW Cabinet Fan Coil UnitDokumen29 halamanDaikin FUW Cabinet Fan Coil UnitPaul Mendoza100% (1)

- Revit 2023 Architecture FudamentalDokumen52 halamanRevit 2023 Architecture FudamentalTrung Kiên TrầnBelum ada peringkat

- PDS (OTO360) Form PDFDokumen2 halamanPDS (OTO360) Form PDFcikgutiBelum ada peringkat

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- Specialty Coffee Association of Indonesia Cupping Form (ARABICA)Dokumen1 halamanSpecialty Coffee Association of Indonesia Cupping Form (ARABICA)Saiffullah RaisBelum ada peringkat

- Asuhan Keperawatan Pada Klien Dengan Proses Penyembuhan Luka. Pengkajian Diagnosa Perencanaan Implementasi EvaluasiDokumen43 halamanAsuhan Keperawatan Pada Klien Dengan Proses Penyembuhan Luka. Pengkajian Diagnosa Perencanaan Implementasi EvaluasiCak FirmanBelum ada peringkat

- ULANGAN HARIAN Mapel Bahasa InggrisDokumen14 halamanULANGAN HARIAN Mapel Bahasa Inggrisfatima zahraBelum ada peringkat

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2259)

- Acampamento 2010Dokumen47 halamanAcampamento 2010Salete MendezBelum ada peringkat

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- Power System Planning and OperationDokumen2 halamanPower System Planning and OperationDrGopikrishna Pasam100% (4)

- Getting Returning Vets Back On Their Feet: Ggoopp EennddggaammeeDokumen28 halamanGetting Returning Vets Back On Their Feet: Ggoopp EennddggaammeeSan Mateo Daily JournalBelum ada peringkat

- Chem Resist ChartDokumen13 halamanChem Resist ChartRC LandaBelum ada peringkat

- En 50124 1 2001Dokumen62 halamanEn 50124 1 2001Vivek Kumar BhandariBelum ada peringkat

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (121)

- College of Computer Science Software DepartmentDokumen4 halamanCollege of Computer Science Software DepartmentRommel L. DorinBelum ada peringkat

- GTA IV Simple Native Trainer v6.5 Key Bindings For SingleplayerDokumen1 halamanGTA IV Simple Native Trainer v6.5 Key Bindings For SingleplayerThanuja DilshanBelum ada peringkat

- Settlement Report - 14feb17Dokumen10 halamanSettlement Report - 14feb17Abdul SalamBelum ada peringkat

- The Piano Lesson Companion Book: Level 1Dokumen17 halamanThe Piano Lesson Companion Book: Level 1TsogtsaikhanEnerelBelum ada peringkat

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)