Residential Tourism Causing Land Privatization and Alienation New Pressures On Costa Rica Coast

Diunggah oleh

pangea2885Deskripsi Asli:

Judul Asli

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Residential Tourism Causing Land Privatization and Alienation New Pressures On Costa Rica Coast

Diunggah oleh

pangea2885Hak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Development, 2011, 54(1), (8590) r 2011 Society for International Development 1011-6370/11 www.sidint.

net/development/

Local/Global Encounters

Residential Tourism Causing Land Privatization and Alienation: New pressures on Costa Ricas coasts

FEMKE VAN NOORLOOS

ABSTRACT Costa Rica has recently seen its tourism industry change with the arrival of residential tourism. Neo-liberal policies aimed at attracting foreign direct investment have played a large role in this change; and the foreignization and privatization of land has been the result. Femke van Noorloos examines how the north-western coast of Costa Rica has become a transnational space, in which struggles over resources and development models will continue to arise. KEYWORDS tourism; lifestyle migration; land grabbing; Latin America; community responses; resource pressures

Introduction

In recent years Costa Rica has become an important destination for migrants from the United States, Canada and Europe to buy their piece of paradiseand live their dreams. This reflects a wider process in which western populations have increasingly made the move to such far-away corners of the world as Central America in search of paradise: a higher quality of life for a lower cost ^ but also an investment opportunity. Important triggers for these developments have been the increased global connectivity and neoliberal policies; it is now much easier than before to become the owner of houses and land in distant locations, provided that one has the financial possibilities to do so. Thus various developing countries are experiencing the progressive development of a residential tourism sector.1 Given its focus on land and housing, residential tourism has a potential to cause more land pressures than short-term tourism. Tourism and real estate are highly attractive for developing countries in dire need of foreign direct investment (FDI) and employment. However, residential tourism is also a main driver of land privatization, speculation and alienation; and in addition it puts strain on other resources. Even Costa Rica, notwithstanding its image as an ecological small-scale tourism destination, has recently seen parts of its coasts (particularly the north-western coast) converted into important residential tourism destinations. As a result, strong pressures on land, water and the environment have emerged. It shows increased signs of enclave creation: a process whereby a tourism destination becomes

Development (2011) 54(1), 8590. doi:10.1057/dev.2010.90

Development 54(1): Local/Global Encounters

commoditized, privatized and regulated by outside values and needs (Saarinen, 2004). The capitalist forces of international tourism are transforming Costa Ricas north-west coast into a transnational economic landscape (Torres and Momsen, 2005). The privatization and liberalization of coastal land in Costa Rica is not the result of changes in official policy or law; rather, it can be traced back to more subtle, de facto policy processes. The law on the maritime-terrestrial zone (ZMT) establishes rules for the use and protection of the first 200 m of coastal land: the first 50 m are inalienable public land, and for the remaining 150 m land concessions are issued by municipalities and the National Tourism Institute (ICT) on the basis of zoning plans.2 However, in practice, zoning plans are mostly absent or not applied in practice (CGR, 2007); furthermore, the limitations on foreign ownership and multiple concessions are often avoided by establishing corporations; and concessions are in practice given out for long periods of time. In this way, extremely low-taxed concessions on coastal land, which was originally meant to serve the public benefit, are granted to large tourism developers without adequate environmental control (CGR, 2007). The residential tourism boom in Costa Rica has been aided by national-level policies, whereas counterbalancing institutions (local government and state institutes, e.g. the environmental ministry) have been extremely weak and slow to respond to rapid change.

Policies promoting large-scale tourism

Costa Ricas state policies have been main triggers for the transformation of parts of the country into large-scalesun and beachand residential tourism destinations from the late 1990s. Although visa regulations for foreign retirees have been somewhat restricted, in many other policy areas the Costa Rican government shows clear signs of favouring large-scale and residential tourism growth. Attracting FDI and creating advantageous conditions for investment have been main priorities for the Costa Rican government in recent decades. Tourism investors are granted direct tax incentives, and already since the 1970s there have been attempts to develop a state-planned tourism resort on the north-west coast, the Tourist Pole Gulf of Papagayo (Salas Roiz, 2010). A variety of other policies have also boosted residential tourism growth in recent years. One example, related to tourism, concerns the implementation of largescale infrastructural projects such as the building of the Liberia International Airport, allowing for a large number of charter flights to be run directly between the United States and the north-western coast. Also, the Costa Rican government has been directly involved in closing some of the deals for large tourism projects: by using executive decrees, processes are speeded up and strict environmental regulations are avoided (Semanario Universidad, 2009). Furthermore, it is intended to promote investment in marinas by modifying the original marina law (No. 7744), allowing for longer leases and easier approval without previous environmental studies. In the coastal areas of Papagayo Peninsula, Playas de Coco/Ocotal and Playa Conchal, tourism developers have signed agreements with the national water institute, thereby making it possible to pump large amounts of water into the tourism projects.

Residential tourism in Guanacaste: some facts

From about 2002 until 2008, Costa Ricas residential tourism industry has experienced dramatic growth, reflected in FDI numbers: whereas tourism and real estate respectively made up 15 percent and 5 percent of total FDI in 2003, by 2007 these percentages had increased to 17 percent for tourism and 34 percent for real estate.3 In 2010, according to rough estimates, 50,000 residential tourists (about 1 percent of the population) were living in Costa Rica (pers. comm. ARCR Costa Rica). Costa Ricas north-western coast (Guanacaste province) has been at the forefront of residential tourism developments.4 Tourism demand and offer have experienced profound change there: since the 1990s the tourism offer has been dominated by large corporations including national and foreign investors, as well as international

86

van Noorloos: Tourism, Land Privatization and Alienation

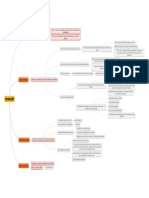

Figure 1: Number of residential tourism developments in Tamarindo and Playas del Coco areas (north-west Costa Rica). blicas y Transporte, Costa Rica Source: Authors research, cartography adapted from Ministerio de Obras Pu

hotel chains (Programa Estado de la Nacio n, 2007). In the two main micro-regions of tourism development in north-western Costa Rica (the Tamarindo area and the Playas del Coco area), a total of 145 completed residential tourism projects were identified in 2010 (van Noorloos and Zoomers, 2010; Figure 1), with a total of almost 8,000 entities (according to the most conservative estimate). These projects include subdivisions of land, housing developments (residences and apartments), and mixed projects with residential and hotel components. The majority were relatively small apartment complexes, but there were also eight large projects of more than 200 entities. In addition, 45 more projects were announced but their construction was halted or had not yet started; these included some very large projects (Figure 1). This partly reflects the extent to which

the financial crisis has affected the real estate and tourism sectors in Costa Rica. With regard to land ownership, tourism has been engendering a foreignization of the Costa Rican coasts since the 1980s (Honey, 1999): much of the investment in tourism and real estate is of foreign origin. In the aforementioned list of residential tourism developments in Guanacaste, almost 75 percent of the project developments were at least partly of North American origin, whereas 35 percent were at least partly of Costa Rican origin. Combinations of both were thus also common.5 In addition, data on FDI in Costa Rican real estate show that this investment is dominated by North Americans: between 2004 and 2007, 55.2 percent of FDI in real estate originated in the United States, followed by Canada with 7.5 percent.6

87

Development 54(1): Local/Global Encounters

Land alienation, pressures and community responses

McWatters describes three interrelated processes of estrangement that may occur among local populations in residential tourism areas: experiential alienation (as local people feel a loss of connection with their changing locality); commodification of family land into marketable real estate property; and permanent residential displacement (McWatters, 2009). These processes can also be observed in Costa Rica: because of the thin line between commodification of land and physical displacement, land pressures are multiple and complex. Many land transfers from local settlers to external investors have taken place years or even decades ago in Costa Ricas coastal areas: current land sales, rather than transferring land from local to foreign owners, often occur among external parties. The much repeated idea that large local populations have been displaced from their lands because of tourism and land speculation does not hold true for coastal areas in north-west Costa Rica: these areas are characterized by a low population density, and many of the original settler families are still present in the tourism areas. Some of them have sold part of their land, but have maintained a small piece to live on. Thus traditional activities such as agriculture and stock farming have largely disappeared, but land still has a residential function, and is also maintained to pass on to the next generations. Land sale has been mostly voluntary, though making a clearcut distinction between voluntary, distress and forced land sale is difficult, given that wide power differentials and complicated processes of societal change interfere with peoples choices. The sale of land has been intertwined with the change from a largely subsistence-based coastal economy based on agriculture and fishery, towards a service economy based on tourism; the lack of agrarian and subsistence-based options in a time when traditional state support for these activities has greatly declined (Edelman, 1999), may have prompted land sale in coastal areas. Despite the voluntary nature of much land sale, pressures on land are far from absent. Firstly there is the problem of high land price inflation, which makes it largely impossible for local people to buy new land in coastal areas. Thus new generations as well as immigrant labourers are pushed ever more into the interior of the province, where land is still affordable. Furthermore, some of the high-value coastal areas which still remain in local peoples and/or state hands are now under increased pressure from tourism developers, resulting in conflicts and protests by local communities. This concerns, for example, such environmentally vulnerable areas as national parks and parts of the coastal strip. Pressures for privatizing protected nature areas and putting them to tourism use can be found, for example, in Playa Grande (Leatherbacks of Guanacaste National Park) and Ostional (Refugio de Vida Silvestre Ostional). In the case of Playa Grande, the land struggle is one between environmentalists on the one hand and tourism investors/residential tourists (supported by the state) on the other, whereas inhabitants of adjacent towns are divided over the development model to be pursued. Another case is the Ostional reserve, which has traditionally been an exemplary model of sustainable turtle egg harvesting and community conservation (Campbell et al., 2007). Hitherto being home to a small number of modest tourism businesses in recent years, local inhabitants have claimed that the state has plans to expropriate them in order to grant their land to megaprojects for tourism and residential development. The claims are a response to new attempts by the Ministry of the Environment, Energy and Telecommunications (MINAET) to arrange the complicated legal situation of the refuge and its habitation (Matarrita, 2009). The Ostional-based resistance has been the trigger for a much wider coastal protest movement in Costa Rica against large-scale tourism development and land expropriation. Representatives of 54 coastal communities, together with social organizations, have united to struggle for their land and autonomy to pursue their own tourism and development models; this has recently resulted in a law proposal for the recognition and protection of coastal communitarian territories and their historical rights and culture. Much of their

88

van Noorloos: Tourism, Land Privatization and Alienation

concern has to do with the regulation of coastal land, as the following fragment shows:

(y) Law 6043 (y) established a concession regime which seems to have been designed to promote large scale commercial exploitation of the coastal zones. As if this were not enough, in many cases the law is not applied equally for all. (y) Many villages of artisanal fishermen are facing eviction orders and denial of basic public services for occupying the public zone. But the same stringency is not applied when these infringements are committed by large hoteliers or owners of megaprojects. (translated from Spanish by author)7

for protest or conflict: land, water and other natural resources (e.g. biodiversity as a natural amenity for ecotourism) are interrelated, and thus we can speak of multifaceted displacement and conflicts.

Conclusion

In the current globalized context and neo-liberal policy environment, residential tourism has surged in Costa Rica. Central governments active promotion policies, combined with weak local governance and regulation, have generated an ill-planned, market-driven tourism development. Current developments have tended towards outside-driven urbanistic development, including real estate, speculation and construction. Hence issues of land privatization and alienation have come up, intertwined with problems concerning water scarcity and environmental damage. Although much land sale has been voluntary and induced by socio-economic change, the coastal territories still remaining are under great pressure for development, causing social tension. In sum, the north-western coast of Costa Rica has become a transnational space influenced by an increasingly complicated variety of actors (Torres and Momsen, 2005), in which struggles over resources and development models will continue to arise.

Irregularities in the application of the law are rampant; hence the claim by local, poor settlers that their interests are being overrun by tourism developers, as public interest zones are de facto privatized and converted into exclusive (residential) tourism destinations. From these examples two new insights can be drawn on conflict in residential tourism areas. First, the variety of actors involved is larger than often assumed ^ and possibly larger than in areas of only short-term tourism. Not only local communities, but also external actors are often involved in the protests: environmentalists, but also tourism entrepreneurs and residential tourists themselves (Janoschka, 2009). In addition, the loss of a combination of resources is often the reason

Notes

1 Residential tourists are people who move temporarily or permanently to another region or country for reasons related to leisure, lifestyle and/or cost of living, and buy or rent a private residence there. Retirees form an important but not exclusive part of this group. Lifestyle migration is another term often used for this type of mobility (Benson and OReilly, 2009). 2 Law no. 6043: Ley sobre la Zona Mar| timo Terrestre. 3 http://www.bccr.fi.cr/documentos/publicaciones/archivos/Informe%20Sobre%20Flujos%20de%20Inversi%C3% B3n%20Extranjera%20Directa%20en%20Costa%20Rica%202007-%202008%20%20N%2019.doc, accessed August 2008. 4 http://www.bccr.fi.cr/documentos/publicaciones/archivos/Informe%20Sobre%20Flujos%20de%20Inversi%C3% B3n%20Extranjera%20Directa%20en%20Costa%20Rica%202007-%202008%20%20N%2019.doc, accessed August 2008. 5 Data on developersorigin could be traced for 94 of the developments; no substantive differences were found when only large projects were counted (van Noorloos and Zoomers, 2010). 6 http://www.bccr.fi.cr/documentos/publicaciones/archivos/Informe%20Sobre%20Flujos%20de%20Inversi%C3% B3n%20Extranjera%20Directa%20en%20Costa%20Rica%202007-%202008%20%20N%2019.doc, accessed August 2008. 7 Law proposal No. 17.394: Ley de Territorios Costeros Comunitarios, (http://territorioscosteroscomunitarios.com/ newsite/index.php?option com_content&view article&id 113&Itemid 174, accessed May 2010).

89

Development 54(1): Local/Global Encounters

References Benson, Michaela and Karen OReilly (2009) Migration and the Search for a Better Way of Life: A critical exploration of lifestyle migration, The Sociological Review 57(4): 608^25. Campbell, Lisa, Bethany J. Haalboom and Jennie Trow (2007) Sustainability of Community-based Conservation: Sea turtle egg harvesting in Ostional (Costa Rica) ten years later, Environmental conservation 34(2):122^31. blica de Costa Rica) (2007) Memoria Anual 2007, San Jose CGR (Contralor| a General de la Repu , Costa Rica: CGR. Edelman, Marc (1999) Peasants Against Globalization: Rural social movements in Costa Rica, Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. Honey, Martha (1999) Ecotourism and Sustainable Development:Who owns paradise?,Washington, DC: Island Press. Janoschka, Michael (2009) The Contested Spaces of Lifestyle Mobilities: Regime analysis as a tool to study political claims in Latin American retirement destinations, Die Erde 140(3): 251^74. Matarrita,Wilmar (2009) Comunicado del Frente Nacional de Comunidades Amenazadas por Pol| ticas de Extincio n, El Prego n, 8 May. McWatters, Mason R. (2009) Residential Tourism. (De)constructing paradise, Bristol: Channel View. Programa Estado de la Nacio Aporte especial: Diversidad de destinos y desaf| os del turismo en Costa Rica: los n (2007) casos de Tamarindo y La Fortuna, in Programa Estado de la Nacio n (ed.) Decimotercer informe Estado de la Nacio n en desarrollo humano sostenible, San Jose , Costa Rica: Programa Estado de la Nacio n. Saarinen, Jarkko (2004) Destinations in Change: The transformation process of tourist destinations, Tourist Studies 2004(4):161^79. Salas Roiz, Alberto (2010) Polo Tur| stico Golfo de Papagayo, Guanacaste, Costa Rica. Ana lisis del Polo Tur| stico Golfo nico gubernamental de concesio de Papagayo como un modelo u n tur| stica, in Center for Responsible Travel (ed.) The Impact of Tourism Related Development along Costa Ricas Pacific Coast, Washington, DC/Stanford, CA: Center for Responsible Travel. Semanario Universidad (2009) Presentan recurso de amparo para proteger bosque en Punta Cacique, Semanario Universidad, 14^20 January. Torres, Rebecca Maria and Janet D. Momsen (2005) Gringolandia:The construction of a new tourist space in Mexico, Annals of theAssociation of American Geographers 95(2): 314^35. Van Noorloos, Femke and Annelies Zoomers (2010) Foreignization of Land in Latin America: The case of residential tourism in Central America, unpublished paper for LASA conference.

90

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (73)

- Briefing Note: "2011 - 2014 Budget and Taxpayer Savings"Dokumen6 halamanBriefing Note: "2011 - 2014 Budget and Taxpayer Savings"Jonathan Goldsbie100% (1)

- List of Foreign Venture Capital Investors Registered With SEBISDokumen19 halamanList of Foreign Venture Capital Investors Registered With SEBISDisha NagraniBelum ada peringkat

- Private Equity Real Estate FirmsDokumen13 halamanPrivate Equity Real Estate FirmsgokoliBelum ada peringkat

- Shaking Tables Around The WorldDokumen15 halamanShaking Tables Around The Worlddjani_ip100% (1)

- Harshad Mehta ScamDokumen17 halamanHarshad Mehta ScamRupali Manpreet Rana0% (1)

- RA 7183 FirecrackersDokumen2 halamanRA 7183 FirecrackersKathreen Lavapie100% (1)

- Ginsberg Faye y Rayna Rapp - The Politics of ReporductionDokumen34 halamanGinsberg Faye y Rayna Rapp - The Politics of Reporductionpangea2885Belum ada peringkat

- Asad Talal - Anthropology and The Colonial Encounter - en Gerrit Huizer y Bruce Manheim - The Politics of AnthropologyDokumen14 halamanAsad Talal - Anthropology and The Colonial Encounter - en Gerrit Huizer y Bruce Manheim - The Politics of Anthropologypangea2885Belum ada peringkat

- Asad Talal - Anthropology and The Colonial Encounter - en Gerrit Huizer y Bruce Manheim - The Politics of AnthropologyDokumen14 halamanAsad Talal - Anthropology and The Colonial Encounter - en Gerrit Huizer y Bruce Manheim - The Politics of Anthropologypangea2885Belum ada peringkat

- Riessman Kohker Catherine - Analysis of PersonalDokumen17 halamanRiessman Kohker Catherine - Analysis of Personalpangea2885Belum ada peringkat

- Craig Calhoum - Habitus Field and Capital - Bourdieu Critical PerspectivesDokumen17 halamanCraig Calhoum - Habitus Field and Capital - Bourdieu Critical Perspectivespangea2885Belum ada peringkat

- Harper Douglas - What's New VisuallyDokumen19 halamanHarper Douglas - What's New Visuallypangea2885Belum ada peringkat

- 4 - BANKS S - Identity Narratives by American and CanadianDokumen21 halaman4 - BANKS S - Identity Narratives by American and Canadianpangea2885Belum ada peringkat

- 69 - Ypeij A y E Zorn - Taquile A Peruvian Tourist Island Struggling For ControDokumen10 halaman69 - Ypeij A y E Zorn - Taquile A Peruvian Tourist Island Struggling For Contropangea2885Belum ada peringkat

- 66 - Williams Ay HallTourism and Migration New Relationships Between Production and ConsumptionDokumen25 halaman66 - Williams Ay HallTourism and Migration New Relationships Between Production and Consumptionpangea2885Belum ada peringkat

- 58 - RODRIGUEZ - Fernández Y Rojo International Retirement MigrationDokumen36 halaman58 - RODRIGUEZ - Fernández Y Rojo International Retirement Migrationpangea2885Belum ada peringkat

- 48 - Mosisa A y S - Hipple Trends in Labor Force Participation in The United StateDokumen23 halaman48 - Mosisa A y S - Hipple Trends in Labor Force Participation in The United Statepangea2885Belum ada peringkat

- 19 - ENGEMANN - WALL - The Effects of Recessions Across Demographic Groups.Dokumen43 halaman19 - ENGEMANN - WALL - The Effects of Recessions Across Demographic Groups.pangea2885Belum ada peringkat

- I. Leacock - Introduction EngelsDokumen44 halamanI. Leacock - Introduction Engelspangea2885Belum ada peringkat

- I. Leacock - Introduction EngelsDokumen44 halamanI. Leacock - Introduction Engelspangea2885Belum ada peringkat

- 6 - BENSON M - How Culturally Significant ImaginingsDokumen17 halaman6 - BENSON M - How Culturally Significant Imaginingspangea2885Belum ada peringkat

- 57 - RODRIGUES VICENTE - Tourism As A Recruiting Post For Retirement MigratioDokumen14 halaman57 - RODRIGUES VICENTE - Tourism As A Recruiting Post For Retirement Migratiopangea2885Belum ada peringkat

- Chun Allen Globalization Critical IssuesDokumen65 halamanChun Allen Globalization Critical Issuespangea2885Belum ada peringkat

- Ong A - The Gender and Labor Politics of PosmodernityDokumen32 halamanOng A - The Gender and Labor Politics of Posmodernitypangea2885Belum ada peringkat

- HNIDokumen5 halamanHNIAmrita MishraBelum ada peringkat

- A Presentation ON Amul DairyDokumen12 halamanA Presentation ON Amul DairyChirag PanchalBelum ada peringkat

- Cleared OTC Interest Rate Swaps: Security. Neutrality. TransparencyDokumen22 halamanCleared OTC Interest Rate Swaps: Security. Neutrality. TransparencyAbhijit SenapatiBelum ada peringkat

- Project Study Template - Ver2.0Dokumen14 halamanProject Study Template - Ver2.0Ronielle MercadoBelum ada peringkat

- Revised approval for 132/33kV substation in ElchuruDokumen2 halamanRevised approval for 132/33kV substation in ElchuruHareesh KumarBelum ada peringkat

- Prager History of IP 1545-1787 JPOS 1944Dokumen36 halamanPrager History of IP 1545-1787 JPOS 1944Vent RodBelum ada peringkat

- Impact of Annales School On Ottoman StudiesDokumen16 halamanImpact of Annales School On Ottoman StudiesAlperBalcıBelum ada peringkat

- MTNL Mumbai PlansDokumen3 halamanMTNL Mumbai PlansTravel HelpdeskBelum ada peringkat

- HANDLING | BE DESCHI PROFILEDokumen37 halamanHANDLING | BE DESCHI PROFILECarlos ContrerasBelum ada peringkat

- Robot Book of KukaDokumen28 halamanRobot Book of KukaSumit MahajanBelum ada peringkat

- GMG AirlineDokumen15 halamanGMG AirlineabusufiansBelum ada peringkat

- Income Statement Template For WebsiteDokumen5 halamanIncome Statement Template For WebsiteKelly CantuBelum ada peringkat

- (Topic 6) Decision TreeDokumen2 halaman(Topic 6) Decision TreePusat Tuisyen MahajayaBelum ada peringkat

- PPE0045 MidTest T3 1112Dokumen6 halamanPPE0045 MidTest T3 1112Tan Xin XyiBelum ada peringkat

- By: John Paul Diaz Adonis Abapo Alvin Mantilla James PleñosDokumen9 halamanBy: John Paul Diaz Adonis Abapo Alvin Mantilla James PleñosRhea Antonette DiazBelum ada peringkat

- IntroductionDokumen3 halamanIntroductionHîmäñshû ThãkráñBelum ada peringkat

- EPRescober - Topic - 4PL and 5PL - LogisticsDokumen6 halamanEPRescober - Topic - 4PL and 5PL - LogisticsELben RescoberBelum ada peringkat

- Keegan02 The Global Economic EnvironmentDokumen17 halamanKeegan02 The Global Economic Environmentaekram faisalBelum ada peringkat

- Kheda Satyagraha - 3291404Dokumen27 halamanKheda Satyagraha - 3291404Bhaskar AmasaBelum ada peringkat

- Cloud Family PAMM IB PlanDokumen4 halamanCloud Family PAMM IB Plantrevorsum123Belum ada peringkat

- Idbi BKDokumen5 halamanIdbi BKsourabh_kukreti2000Belum ada peringkat

- Recasting FSDokumen1 halamanRecasting FSCapung SolehBelum ada peringkat

- PRQNP 11 FBND 275 HXDokumen2 halamanPRQNP 11 FBND 275 HXjeevan gowdaBelum ada peringkat

- June 2010 (v1) QP - Paper 1 CIE Economics IGCSEDokumen12 halamanJune 2010 (v1) QP - Paper 1 CIE Economics IGCSEjoseph oukoBelum ada peringkat