Mystic Rites For Permanent Class Conflict

Diunggah oleh

sandanandaJudul Asli

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Mystic Rites For Permanent Class Conflict

Diunggah oleh

sandanandaHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

www.sagepublications.com DOI: 10.1177/026272801203200102 Vol.

32(1): 2138

SOUTH ASIA RESEARCH

Copyright 2012 SAGE Publications Los Angeles, London, New Delhi, Singapore and Washington DC

MYSTIC RITES FOR PERMANENT CLASS CONFLICT: THE BAULS OF BENGAL, REVOLUTIONARY IDEOLOGY AND POST-CAPITALISM

Fabrizio M. Ferrari

Department of Theology and Religious Studies, University of Chester, Chester, UK abstract Locating itself amidst current debates on post-modern analyses of mysticism, particularly academic debates on the Bauls of Bengal, this article discusses issues of cultural transformation as a result of gentrication and globalisation. It combines the authors ethnographic research and a methodology mainly derived from Italian Marxist critique (Antonio Gramsci, Ernesto de Martino, Antonio Negri and Paolo Virno). The article examines the reication of mysticism and the process of rehab, as imposed by Bengali bourgeoisie via the Tagorian archetype and the Western show business on the Bauls, to cleanse their image from inconvenient traits. Suggesting an interpretation of radical materialist mystics as multitude and viewing professional Bauls as people, this research explores how the construction of a myth has ultimately penetrated contemporary society at all levels, including academic circles. keywords: Bauls, Bengal, folklore, Italian Marxism, Marxist critique, multitude, mysticism, people, philosophy, post-capitalism

Marginalisation and Rehabilitation

The Bauls of Bengal represent the idiosyncrasies and contradictions of Bengali mysticism and esotericism at their best. Bauls are celebrated as a sect that believes in the divinity of the human being. They tend to reject what is supposed to be the conventionally institutionalised sacred and deliver their message and teaching mostly through songs (ba ul giti). From the end of the nineteenth century, when the Nobel laureate poet Rabindranath Tagore expressed his deep appreciation for Baul songs and philosophy, Bengali gentry fell for them. Nobody, however, was ready or willing to accept the dark side of the Bauls. Traditional Baul ritual practices have a strong sexual avour and Bauls indulge in consumption of intoxicants. For these and other reasons, such as their low caste origin and anti-social behaviour, the Bauls have a

22

South Asia Research Vol. 32 (1): 2138

history of marginalisation. Only those Bauls who abandonedor kept secrettheir rituals were able to nd patrons and gain, along with mundane commodities, the status of mad mystic. A further phenomenon contributed to change the traditional role of the Baul and the rise of Baulism. From the 1960s, thanks to Bob Dylan and his entourage rst and Peter Gabriels World of Music, Art and Dance (WOMAD) project later, the Bauls became an international phenomenon and inspired the birth of Western Bauls. Many Bauls still practise the rituals of an ancient esoteric tradition in remote areas of West Bengal and Bangladesh. They earn a life from singing and begging during religious festivals, or performing in small villages. Despite being the holders of a 600 years old tradition, to contemporary Bengali bourgeoisie (bhadralok) they still are dirty beggars. True Bauls are dancers and divine mystical minstrels who live an ecstatic and/or ascetic life preaching the divinity of man and universal brotherhood (Bhattacharya, 2002). This article discusses issues of cultural transformation as a result of gentrication and globalisation. Moving from ethnographic research and a methodology mainly derived from Italian Marxist critique, specically Antonio Gramsci (1971, 2007), Ernesto de Martino (1951, 1993, 2002), Antonio Negri (2003) and Paolo Virno (2004), I examine the reication of mysticism and the process of rehabilitation (rehab) imposed by Bengali bourgeoisie and the Western show business on the Bauls to cleanse their image from inconvenient traits.

A Bauls Dilemma: Materialist Practitioner or Mad Mystic?

Bakhunin (1871) asked who is right, the idealists or the materialists. He argued that the question, stated in this way, makes hesitation impossible and demands a clear-cut answer. He took the view that, undoubtedly, the idealists are wrong and the materialists are right. One of the rst things I learned from the early stages of my eldwork in West Bengal was how different the professional Bauls advertised in the global market, through CDs, DVDs, the World Wide Web, international festivals or romanticised ethnographies, are from Bengali ba ul panth s. Similar issues have been investigated by scholars who challenged the global perception of the Bauls.1 In particular, I nd of the greatest interest post-modern discourses on and around the differences of the early nineteenth century Tagorian Baul and esoteric practitioners, whom Openshaw (2002) calls bartama n panth s. As history is crucial to understanding the evolution of Bauls in different communities, specically Bengali rural areas and gentried circles, Western and Bengali Orientalists, Western counterculture, academic centres, the global show business, Bengali folk and pop music, this article reects in Marxist terms on the notion of time and history as privileged arenas for revolutionary programmes. In particular I examine here academic categories such as mysticism and folklore and their progressive

Ferrari: Mystic Rites for Permanent Class Conict

23

construction within culture after moments of rupture, which I identify as rehab. Such interruptions are discussed as caesura, a concept identied by Foucault (2007: xii) as an originative tool that establishes the distance between reason and non-reason. But who is the signier of reason? Mysticism and folklore are receptacles for dramatic social rites of passage imposed by the superstructure on an idealised subordinate to make a political and economic agenda viable. In the case of the Bauls, the divine madness, advertised by Tagore and Bengali bourgeois intellectuals rst and by contemporary show business later, is conducive to the denition of new sites of spirituality: Bengaliness and to some extent Indian national identity as well as folk-music. However, these processes have led to a restraint of meaning (reason)or at least to its domesticationto the point that Bauls are no longer makers of history or owner of their time, as proposed respectively by de Martino and Negri. The liberation they advertise today is just a commercial one, because it lacks the Gramscian work of self-knowledge and only relies on proliferation of meanings, a process dened as a self-multiplication of signicance, weaving relationships so numerous, so intertwined, so rich, that they can no longer be deciphered except in the esoterism of knowledge (Foucault, 2007: 16). But the bourgeois Baul have lost such knowledge, or nd it not benecial to use it. Conversely, radical Bauls, to retain Openshaws words (2002: 1923), are bartama n panth s, materialists professing a philosophy that emphasises sensory experience and bodily perception. Ironically mystical Bauls sold their soul to the market for money, or a place in the sun, while materialist Bauls will stay poor, neglected and marginalised despite being the repositories of a philosophy of deliverance. In that they mirror Gramscis notion of folklore as oppositional culture, one determined by potentially progressive features. This particular aspect, discussed at length by Ernesto de Martino (1951), is referred to by him as progressive folklore. This is dened as a conscious proposal of people against their own subaltern condition and a way to express their struggle for emancipation in cultural terms. Yet folklore, according to de Martino, cannot be analysed as an isolated phenomenon only responding to larger patterns of oppression. Folk culture should not be discussed at the same level as hegemonic culture. The subaltern world is inextricably linked to the present, but this present does not only respond to the history of its superstructure. Rather it is the actualisation of myth within the limits imposed by historical contingencies. The philosophy of materialist Bauls represents a collective drama and an attempt to struggle in order to secure emancipation while maintaining identity. Gramsci explicitly noted this when he commented on the opposition between vernacular religions and the religious institute. In particular, he observed that the real philosopher is, and cannot be other than, the politician, the active man who modies the environment, understanding by environment the ensemble of relations which each of us enters to take part in.2 It appears that esoteric ritual practices are for bartama n panth s an exclusivist tool designed to achieve a form of social or political sama dhi (cessation), while for the Baulsand their patronsthey represent an inconvenience on the way of their professed inclusivism. South Asia Research Vol. 32 (1): 2138

24

South Asia Research Vol. 32 (1): 2138

An examination of three core ritual practices among bartama n panth s, namely, the absorption of the four moons, ritual sex and consumption of drug, sustains my argument. Such practices have attracted the attention (whether genuine or lurid fascination) of scholars, Orientalists, bourgeoisies, counterculture movements and the media industry. These have in various ways contributed to the process which has led to the Bauls rehab. The absorption of the four moons (ca ricandra sa dhana, see Jha, 1996) is a ritual variously described to me as a way to merge with the divine (in Baul philosophy, maner ma nus ., the human being of the heart) and to go beyond the malefemale dualism that features in the sensible world. The four moons used in this ritual are stool (bis ta .. or ma . thi ), urine (mutra or rasa), menstrual blood (rajas or ru pa) and semen ( s ukra or rasa). They respectively represent the four gross elements pervading the sensible world: earth, water, re and air. These are usually gathered in a ritual pot (kuja ), blended dhaka with cow milk, coconut milk, camphor and sugar,3 and are consumed by both sa and sa dhika (male and female practitioners).4 Ritual sex (maithuna) is practised as a way to control every physical impulse so as to experience feelings as natural or coemergent (sahaja) and to be freed from egotism (aham karan nus ja cakra, a). Bauls believe that the maner ma dwells in the a the lotus-shaped discus on the top of the head. Sexual activity makes it swim down in the form of a sh (m n ru p) towards mu la dha ra cakra, on the perineum, where it is empowered by the female energy (kun d alin s akti ). Once the feminine element has awakened the masculine one, the sh will move back towards the head piercing all the cakras. According to some of my informants, ritual sexual intercourse is supposed to take place on the third day of the female companions menstruation, the day of the new moon (ama basya ). At that moment (which is emphatically called maha yug) the three streams of blood that constitute a womans menses (rajo ru p), that is, ka run ya ba ri (the water of compassion), ta run ya ba ri (the young water) and la van ya ba ri (the charming water), join together in the female genitalia thus forming triven . As for the performance itself, sexual union is divided in four different phases: (a) niha rana (inner observation), in which the Baul is absorbed in deep meditation and repeats the initiatory mantra; (b) spars ana (contact), or physical union between sa dhaka and sa dhika; (c) ma rjana, or rubbing; (d ) stambhana, or retention, where the sa dhaka has to retain his semen. During this last stage (also called u rdhbareta h) the male practitioner is expected to absorb womans menstrual blood through his penis so as to let it be melted with semen. It is important to notice that women are not required to engage in this practice as they already contain both the female and male principles; they are whole beings (Hanssen, 2002: 370). By practising the triple retention, of breath, thought and semen, desire is annihilated; the sh (maner ma nus ra cakra (or ) reaches sahasra sahaja cakra) over the top of the head where sahaja sama dhi is nally experienced. This particular condition has mental and physical consequences, as explained to me. The practitioners are liberated while alive. They are beyond worldly categories. This form of absolute control is what bartama n panth s call madness, pa gal tattva.5

Ferrari: Mystic Rites for Permanent Class Conict

25

The third ritual considered here is the use of psychotropic substances. Derivates from the Cannabis sativa such as ga ja (marijuana), bha n g (a cold drink made of milk, sugar, spices and marijuana) and opium allow a progressive slowing of the internal ve aerial winds ( pacapra n n na, downward air, sama na, the as): pra a, inhaled air, apa abdominal circular air, uda na, upward air, and vya na, the air owing within the whole body. By consuming ga ja , practitioners progressively slow their respiratory rhythm (da mer ka j), an action resulting in total control of the ve senses and ultimately in detachment from passions. Although Bauls are not marginalised for the use of drugs per se (which in fact does not constitute a taboo in South Asia), the combination of illicit substances with illicit behaviour generates blame. It thus appears that the state of divine madness (divyan mada) so much loved by Bauls fans of every extraction is hardly a consequence of mental instability. Rather it is the result of utter control and concentration. Unlike Bauls who indulge in smoking hemp on the sly and behave errantly only to please an Indian and Western gentried public who expect them to be pa gal (mad), bartama n panth s aim to control their experiences through their body. The notorious anti-social behaviour of many Bauls can be interpreted as a political and strategic statement constructed on aesthetic ritual patterns. Like insurrectionary anarchists, bartama n panth s advocate a revolutionary theory and practice that emphasises the opposition to superstructural forms of organisation and supports a more informal web of organisation built on afnity (initiation, shared practices and secret jargon). As has been observed, theirs is not dharma but mat, opinion (Jha, 1996: 68). With their denial to be part of larger bourgeois discourses, including show business, whether local or global, bartama n panth s enact permanent class conict. Even further, materialist Bauls express protest against the system by enacting and embodying an exit strategy. As many renouncing traditions, bartama n panth s eschew footlights in the same way the Tagorian Baul cannot survive without them (Bergunder, 2010: 25). Investigating radicalism among the Bauls of Bengal should therefore entail an analysis of defection in both cultural and political terms. Virno (2004: 70) discusses this as a trajectory that modies the conditions within which the struggle takes place, rather than presupposing those conditions to be an unalterable horizon. Unlike Tagores inclusive performance, which provided the Bauls with Otherised imaginative horizons, a set of intertwined landscapes featured by the licit and illicit desires of the middle class as well as its dreams and dreads (Crapanzano, 2004: 14), defection is the ultimate strategy of civil disobedience.

The Radical Multitude and the Tagorian People

Bauls are a highly fragmented order with no charismatic or institutional leader, central scripture or place of worship. Under the label Baul a number of taxonomies coexist: a ul, karta bhaja , tantrika , phak r, bhakta, etc. Esoteric practices may differ to a great extent according to a number of factors (denomination/afliation of a teacher, lineage, South Asia Research Vol. 32 (1): 2138

26

South Asia Research Vol. 32 (1): 2138

gender of the practitioner, cultural environment, education and wealth). Dening Baul thus becomes an academic necessity. The present article contributes to this debate by focusing on the distinction between multitude and people as theorised by Negri and Virno. This is done for two main reasons. First, Italian radical Marxism offers a valuable way to discuss religious phenomena emerging from political agendas and their necessity to respond to the global market. Second, Baulism is now a world phenomenon and as such it mirrors a crisis that conates a number of economic and social issues. Among these, I examine modern and post-modern coercive ways to cleanse mysticism in order to make it a presentable commodity to the twenty-rst century bourgeoisie. According to Negri (2003), who derived his formulation from Spinoza and Hobbes, multitude is a concept opposed to Empire:

The multitude is the real productive force of our social world, whereas Empire is a mere apparatus of capture that lives only off the vitality of the multitudeas Marx would say, a vampire regime of accumulated dead labor that survives only by sucking off the blood of their living. (Hardt and Negri, 2000: 62)

Materialist Bauls act as a conscious multitude in a cultural landscape dominated by Empire, an arena where different middle-class forces operate simultaneously. Building on Hardt and Negri (2000), Virno (2004: 12) emphasises a classic Marxian notion while citing an earlier author: The multitude is a force dened less by what it actually produces than by its virtuality, its potential to produce and produce itself (italics in the original). For decades most studies on the Bauls have been carried out under the intimidating shadow of Rabindranath Tagore. Before Tagore, Bauls were considered nothing but beggars, properly speaking, they are a godless sect, which makes it a point to appear as dirty as possible (Bhattacharya, 1968: 381). Although there are no elements to infer that Tagore had nothing but sincere fascination for the poetical message delivered by the Bauls, it has to be maintained that his interpretive exegesis ended up with the appropriation and re-presentation of one selected potential only, namely bourgeois spirituality. Tagore himself admitted that Bauls have a philosophy, which they call the philosophy of body, but they keep it secret; it is only for [the] initiated (Tagore, 1922, quoted in Dimock Jr., 1959: 86). Yet by attracting them in an alternative history, Tagore makes use of reactionary mysticism, or what Negri (2003: 21) denes as a construction built around the unreality of time, and thus of its exploitation, in contrast to revolution, the message of bartama n panth s, born from the pathways of a constitutive phenomenology of temporality. The result is that, on the one hand, we have the development of ritualised exit strategies, which I interpret as renounce (bhek, in Baul terms), actually a form of civil disobedience, the fundamental form of political action of the multitude, provided it is emancipated from the liberal tradition within which it is encapsulated (Virno, 2004: 69). On the other hand, there is the superimposition of the intellectual bourgeoisie, eventually resulting in the mere

Ferrari: Mystic Rites for Permanent Class Conict

27

quantication of ritual quality (i.e., meaning) and therefore leading to the negation of any dialectic signicance (Negri, 2003: 27). The philosophy of the bartama n panth s coincides with the struggling aim of the multitude while the annihilation of resistance tendencies (folklore) denes Bauls as people, an anonymous mass of individuals directed by Empire in performative actions, built on the hegemonic control of aesthetic criteria but ultimately delivering no meaning. Eventually I agree with Virno (2004: 23) when he concludes that: If there are people, there is no multitude; if there is a multitude, there are no people. Following Tagores lesson, Baul poetry has been explained as an attempt to stress the unity of men in front of God and the presence itself of God in the human body. This led to the identication of Bauls as holders of a universal love philosophy. However, rather than followers of the maner ma nus (man of the heart) they should be considered proponents of the maner lok (people of the heart), where the heart is nothing but capitalist order. A new form of Baul mysticism was born as well as a new gure: the professional Baul. The Bauls of Birbhum, the district in West Bengal where Tagore founded Vishwabharati Vishvavidhyalaya, better known as Shantiniketan University, are the perfect example to illustrate such parabola. They are mostly wandering Vais n ava minstrels dressed in orange or saffron patched robes who sing the divinity of Man. Their performances mirror the Tagorian patterns perpetuated through media, tourism agencies, cultural associations and national and international festivals in South Asia and abroad. Baul clothes, their repertoire, dance and gestures are standardised while songs tend to be always the same, especially in terms of lyrics. I had the chance to observe this when travelling with a small party of four Bauls (three males and one female) from a village near Raiganj (Uttar Dinajpur district). On a pilgrimage route to Varanasi, we received hospitality from an old Bengali gentleman. A fervent Tagorian educated at Shantiniketan and abroad, also a poet and a visual artist, our host organised some sessions with the Bauls who were asked to perform for friends and family. The patron told them what to sing, what to wear, how to comb their long hair and to act like a Baul (e.g., raising the arm holding the ekta ra towards the sky and dancing in small circles). In a nutshell, they were requested to do the pa gal . Needless to say, I was disappointed. This must add to the fact that I myself was expecting something mystical during the weeks we spent together. Instead, my fellow travellers spent their time sleeping, smoking, joking and chatting about the most disparate issues, from politics to cricket, Bollywood hits and family issues. Only at a later stage, and after several meetings, two of my informants, both in their mid-forties, discussed with me some of the old songs as well as ritual practices. They wanted me to know the majority of Bauls, especially in Birbhum, are now businessmen or, in some cases, junkies who nd a justication for their addiction in the Bauls lifestyle. Those still singing songs containing teachings related to sexo-yogic practices or the use of intoxicants are often not able to understand them, or claim there is no such message. Also they revealed to me (I had this conrmed in the following years by other panth s) that [y]ou dont South Asia Research Vol. 32 (1): 2138

28

South Asia Research Vol. 32 (1): 2138

need to be a singer, you dont need to sing, to be a Baul. The following song (recorded on 16 January 2001) and attributed to Madan Phakir is a good example of twilight language (sandhya bha sa ) or upside-down language (ult sa ), a technique used a bha by Bauls to transmit secret teachings and practices:

One moon has touched the body of another moon: I keep on thinking about it, but what can I do? From the daughters womb is the mothers birth: I keep on thinking about it, but what can I do? There was a girl of six months, after nine months she conceived and eleven months later three children were born: Who will be the phakir? With sixteen arms and thirty-two heads, the child is speaking in the womb. Who are his mother and father? This is the question. There is a room without doors, there is a man who cant speak. Who supplies the food? Who gives the evening lamp? Madan Sa i Phakir says: The son dies touching his mothers body. The one who will understand these words, will obtain the condition of phakir.

My informants explained the text to me as follows:

So we have two moons, one is the maner ma nus . This is melted in semen, the second moon. So you have to focus on your body. The maner ma nus this [is the] moonoats in seminal liquid which is in the a ja cakra. Then the rst moon meets the womans blood on the day of the new moon (ama basya ). Listen the blood of the woman is at the origin of power. So the woman too must focus on body. The sexual energy of man and woman during maithun [is] like the work of a mother. Listen it is power and nurturance. Now, I tell you on the 6th day of the womans menstrual cycle [he hums: chay ma se ek kanya chilo], she produces ova. Then on the 15th day, after nine days [he hums: na y ma se ta r garba holo] they are ready to be fecundated. And after eleven months [he hums: ega ra ma se tinti santa n] three children [are] delivered Now, if you can do this6[to be] successful, I meanthen you will leave the pain, this world understand? The woman is so powerful: [she is] mother (ma ), daughter (meye) and virgin (kanya ). When I do maithun I am different. [There are] no more senses (sight, hearing, touch, smell and taste, the ve karmendr yas). No more organs of senses (eyes, ears, skin, nose and tongue, the ve janendr yas). No more enemy forces (wrath, pride, greed, illusion, envy and lust, the six ripus]. No more the thirty-two na d s (veins) that limit your body. [The body is] just made of holes (eyes, ears, nostrils, mouth, anus and sex organ). I need to feel naturally. So who are my mother and father? I tell you what:

Ferrari: Mystic Rites for Permanent Class Conict

there is no more mother-father, male-female. [I] dont exist. I eat the four moons. With my [female] friend and then I see light you know knowledge, Ishwar. But you have to do it with a woman. And destroy passion.7 (Debendranath Das and Sarit Baba (pseudonyms), eldwork diary, 20 January 2001)

29

This song is precisely the kind of lyric Tagore would have never considered for a Baul anthology. But the question here is not whether Tagore was averse to esotericism and ritual erotic practices (cf. Tagore, 1922: 835). Tagore was simply not a post-modern social scientist (Sen, 1952: 1223; Zbavitel, 1961: 1213). The domestication of the materialist Baul is not only an aesthetic choice but a hegemonic move performed through caesura (or rehab) by the people on the multitude. This reminds us of the main problem, namely, the relation between history and religion and the need to withdraw the latter from the naturalist stances of the former. In this operation, de Martinos analysis of time as both a function resulting in economic movement and a metaphysical notion transcending the reication of economic contingencies is extremely useful (de Martino, 1993: 268). History and time are problematised in cultural terms to individuate the action of unevenness at the origin of the crisis of presence (de Martino, 2002: 433). de Martino also explores ways in which the ctitious construction of history might eventually contribute to the exploitation of the subaltern Other, thus dening the reaction of the multitude (i.e., progressive folklore) and the adaptation of the people. Both de Martino and Negri converge when the latter says that time is a theological scandal. Therefore reality is a constrained unity, that is, dominable space (Negri, 2003: 29, italics in the original). This analysis is reminiscent of the particular sensibility de Martino developed for time and space of the subaltern, their history and metahistory, or myth. Such dialectic passes here through the lesson of Gramsci against the positivistic barbarism of reductionist stances, including Leninism and Stalinism. In particular, it is important to observe how Gramsci gave back to matter the continuously developing historical meaning of the human sensible activity in society and its outcomes (de Martino, 2002: 439). More precisely, time in Marx is not only the route out from the contradiction of change, not only the instrument that constructs the effective possibility of changetime is also the tautology of life. To begin with, in Marx, time is given to us as the matter of equivalence and the measure of the equivalent (Negri, 2003: 35). Bauls are thus dominated not because they have been offered, and accepted, an equivalent, yet more appealing, alternative to their history. In fact, it is the perception of the measure of their time (history and myth) that lured them towards apparently greener pastures. Their praxis is the acceptance of the domestication that colonial and post-colonial culture inevitably suffered at the hands of global capitalism and its contemporary manifestations. Ritual practices such as ingesting bodily uids, illicit sex and consuming drugs are known to Bengali bourgeoisie (Jha, 1996), but they represent a monstrosity, both in terms of erratic, unconventional, wrong behaviour as in its original meaning of South Asia Research Vol. 32 (1): 2138

30

South Asia Research Vol. 32 (1): 2138

portent, something that warns out. As such they carry a counter-meaning or the anti-Gramscian notion of folklore as something exotic. Divine madness is expected to be achieved through music, dancing and singing. The sponsors of major festivals, especially in India, are not interested in Baul esoteric practices. They prefer to have professional Baul, or even fake Baul, singing traditional Bengali songs, Rabindra-san git or selected Baul hits. Baul music is now a genre on its own that follows the patterns dictated by Tagore and his entourage. The poet, who ended up being called the greatest of the Ba uls of Bengal by Dimock (1959), is thus responsible for a phenomenon which eventually changed forever the public image of Bauls as panth s. Whether his intentions result from personal sensibility, poetic choice or prudery, Bengali bhadralok have accepted such a model and passed it onto the West.

The Eastern Hippie Baul and the Western Neo-radical

In his larger analysis of folklore, Gramsci (1971: 130) asked: When can the conditions for awakening and developing a national-popular will be said to exist? The question is germane to the present analysis on a number of levels. In posing his doubt, Gramsci makes a point on how to reconcile different processes of production of culture in the same society. Yet in the case of the Bauls this is even more complicated. With globalisation, migration and post-capitalism, in other words the rise of Empire, many claim authority, and authorship, over Bauls by-products. We can thus observe the creation of conicting systems built on the notions of territory (the environment of the multitude) and map (the projection of the people). But in the age of postcapitalism, what the global audience is given is the map of a territory, and the map, we should remember, is never the actual territory. This projection works well if we consider two contemporary developments of Baulism, namely, the merging of the Bauls into Western counterculture and the birth of the Western Bauls. These two phenomena are briey discussed here to show the resistance of the multitude/people dichotomy and the perpetuation of conicting maps throughout diverse territories. The Bauls made their appearance in the West thanks to the 1960s counterculture. Five Bauls, including the now world-famous Purna Das Baul and his brother Luxman Das Baul, appeared on the cover photograph of Bob Dylans 1967 John Wesley Harding album. In 1965 they were in the USA after an invitation of Albert Grossman, Dylans manager, who brought them there from West Bengal to perform in various locations. The Bauls were lodging in Dylans house in Woodstock and had the chance to perform with the Byrds, Mick Jagger, Joan Baez, Tina Turner and other icons of pop music. Levon Helm, drummer and singer of the rock group The Band, attended many Baul performances in Woodstock (Helm, 2000: 1578). Eventually an LP was released: Bengali Bauls at Big Pink, produced by Garth Hudson, organist and pianist of The Band. While Bauls in Bengal were either abandoning their tradition in order to survive or living off begging in remote areas, the Baul avant-garde in the West was

Ferrari: Mystic Rites for Permanent Class Conict

31

enjoying the hippie lifestyle. Helm (2006) gives us a vivid website description of the Bauls in Woodstock:

The Bauls had long black hair braided to the waist and were wearing cowboy hats theyd picked up on the drive east from California, where theyd arrived direct from Bengal. (Before heading east in a beat-up old van, theyd played the Fillmore West on a bill with the Byrds.) They loved the bubbling beer sign over our replace, and I played checkers with some of em, and we were laughing pretty hard. I was smoking a chillum with Luxman Das, and I said, Man, thats some good weed. He smiled and said, Very good, but nothing like my father used to smokelittle hashish, little tobacco, little head of snake. I said, Wait a minute. Did you say snake head? And Luxman laughed. Yes, by golly! Chop off head of snake, chop into tiny pieces, put in chillum with little hash, little tobacco. Oh, boy! Very goodrst class high!

Purna Das Baul, after achieving international success and being crowned Baul Samrat (Emperor) in 1967 by the then Indian president Dr Rajendra Prasad, almost 40 years later declared quite contradictorily:

I steer clear of all these [drugs and alcohol]. I am high on music. I dont need chemicals and articial aids. If you ask people, they will tell you how my grandfather [T kur ha Gosa i] and my father [Nabanida s Ks epa Ba ul] would get so high on music that they would lose all control. That is why we are the khepa baul tradition. We are mad. We are in love with life, despite all the sorrow and disappointments it brings. (Nandy, 1999; see also Crovetto, 2006: 846)

The madness that Purna Das mentions here is the distinctive mark of the Tagorian Baul. But while the madness of professional Bauls is a performing technique, to bartama n panth s it is the nal stage of an esoteric path and, most important of all, it is not a public event. Madness allows experiencing cessation (sama dhi) through the total control of physical experience. Purna Das Baul ofcially represents Baul culture, but is also the model of a new spirituality shaped after the examples of Western pop-stars who combine music, philanthropy and spirituality. As an Indian Bono Vox, he collaborates with cultural organisations, academic institutions, NGOs and the government. He wrote the rst manual on being a Ba ul (Baul and Thielemann, 2003). In 2001 he established the Purna Das Baul Academy in San Diego, California, to teach the ancient Indian Baul music and philosophy. A homonymous institution was later founded in Kolkata. According to information collected from his website, Purna Das set up an ashram in Shantiniketan. He and the Bauls living there are involved in local projects such as helping AIDS patients and educating villagers on HIV/AIDS through songs. He also works with various charities and NGOs, hospitals and prisons. Lyrics and music are composed to address and solve problems in spiritually creative ways.8 Professional Bauls had a great impact on the success of Bengali culture. Yet these Bauls were selected as single individuals and not as representative expressions of South Asia Research Vol. 32 (1): 2138

32

South Asia Research Vol. 32 (1): 2138

popular groups (Gramsci, 1971: 397). Mass media and patrons all around the world reinforced this genre and created a successful commercial product. Audiences, in India as elsewhere, want something mystical, but they seem not to understand that mysticism too is a commodity and as such it abides by the laws of the market, irrespective of its agenda. There is nevertheless a different perception of mysticism. Bengali bourgeois audiences want the Tagorian Bauls, and sex and drugs are not expected to be associated to the music and lyrics of their cultural heroes. Westerners, conversely, tend to ignore Bauls practices. Bauls are the typical product of a stereotyped mystical India. If esotericism and erotic rituals as well as ritual use of intoxicants are known, this, apparently, is not an issue. Drawing his analysis from Baudrillard, Urban (2006: 2578) notes that:

the problem for our generation is not so much that we are still in need of sexual liberations or freedom from the prudish taboos of our Victorian forefathers; rather, the dilemma today is perhaps that we have passed through too many sexual revolutions, that we have violated so many sexual, moral, and social taboos that we dont really know what sex is any more. We are thus left in the strange, ambiguous state of a post-orgy world, wondering what sex is even supposed to be about in a post-modern, late capitalist world. (italics in the original)

After decades of massive and lurid advertisement on Tantric practices and Indian eroticism, Western middle class audiences seem to have little problem in accepting sexual intercourse as something mystical. The same must be said for the use of intoxicants such as hashish, marijuana or peyote, which are nowadays associated with new forms of religion and spirituality. Baulism started as a genre forged by Bengali bhadralok and constructed on the outer visual performance of a vernacular esoteric order. Then it turned into the symbol of the Bengali people as opposed to a radical materialist multitude. Eventually, with the establishment of post-capitalism (Empire), Baulism has just become world music and part of the global show business. But following the commodication of Indic spirituality, world music and different forms of meditation, a new religious movement built on Baul spirituality successfully established itself in the West. The followers of the Hohm Sahaj Mandir (Hohm Innate Divinity Temple in Prescott, Arizona) are known as Western Bauls. As their Bengali counterpart, Western Bauls have an ecstatic inclination. As followers of Tantric teachings, Western Bauls have a body-based yogic practice, called kaya sadhana. They believe in the alchemical conversion of gross matter into spirit so they, too, practise chari-chandra-sadhana. Art is believed to be conducive to the divine. The founder of the Hohm Sahaj Mandir, Mr Lee Lozowick (aka Lee Khepa Baul), when asked about relations with Bengali Bauls, says, as cited on the Web by Blacker (2001):

One of the primary aspects of Baul tradition is that communication of the teaching is optimally effective when its experiential. The Bauls are known as itinerant musicians. They encode the esoteric teachings of transformation, including the teachings of their

Ferrari: Mystic Rites for Permanent Class Conict

yoga, into song and choreographed dance and music. Their lyrics are cryptic representations of the teaching itself. People listen to the music and watch the dance and get into a very receptive state where the teaching is kind of organically communicated. [] I think that Liars, Gods and Beggars [Lee Khepa Bauls rocknroll band] has the potential to communicate some essence of the teaching, even if subtly, on a very large scale.

33

The philosophy developed within the Hohm Sahaj Mandir seems very close to that of bartama n panth s. Heavily inuenced by the US 1960s counterculture, multiculturalism and globalisation, the teachings of Lee Khepa Baul are strict and his disciples engage in practices that many professional Bengali Bauls would not dare to perform. [I]f we take a closer look, well nd that this bright man [Mr Lee], who is about fty, embodies Tradition in its most rigorous, profound, and even austere aspects. Practice, exercise, discipline, integrity, consistency are some of his key-words (Khepa Baul, 1993: vi). With their focus on body and action as tools to develop revolutionary potential, Western Bauls embody multitude as opposed to commercial Baul people from the subcontinent. In Negris words, it is the consciousness of the phenomenological relations that from the bodies of individuals extend to the materiality of the collective composition (Negri, 2003: 96, italics in the original) that denes the radicalism and oppositional culture of an exclusivist mystical order. As bartama n panth s, Western Bauls are an underground movement and apparently have not been seduced by the market. It is different for many Bengali Bauls whose production, when sponsored by Bengali badraloks, ends up being patronised. Since Tagore, the relation between Bengali gentry and the Bauls is built on clientelism. Such coercive social action is better understood if we relate it to what Negri (2003: 30) calls the reduction of time to space. By controlling the commodity for sale, in Bengali mysticism, the superstructure controls the history of the Bauls and reduces their territory to an ideological map. Further, as the market just wants the Tagorian archetype, the relation of exploitation between seller, product and buyer redenes the coordinates that allow a cultural (self-)understanding of the Bauls. Eventually liberation is no longer citti-vr itti-nirodha (cessation of the activity of the mind) through bodycontrol but the acknowledgement that ultimate subsumption resides in antagonistic displacement in the capitalist order.

Conclusions

As Susan Sontag (2009: 33) noted:

It is in the nature of all spiritual projects to tend to consume themselvesexhausting their own sense, the very meaning of the terms in which they are couched. (This is why spirituality must be continually reinvented.) All genuinely ultimate projects of consciousness eventually become projects for the unraveling of thought itself.

Three principal aims have been accomplished here. The rst was to locate bartama n panth s within South Asian mysticism and describe problematic esoteric practices. South Asia Research Vol. 32 (1): 2138

34

South Asia Research Vol. 32 (1): 2138

Their sa dhana was discussed as vernacular non-normative ritual performances marked by localism, leading to mystical union with the divine via physical control. The second was to examine how intellectual elites, from Rabindranath Tagore and his acolytes to the contemporary Bengali bourgeoisie, modied the public reception of the Bauls. This was reshaped to respond to the new political and socio-economic needs of an emergent class. Particular philosophical aspects (universal brotherhood and the divinity of man) were emphasised, or even created anew, whilst others were obliterated. Entangled in this process, the new Baul became a geopolitical map representing (and occasionally responding to) capitalist urges. Third, I showed how the rise and afrmation of professional Bauls is a natural consequence of post-capitalism to the point that we should no longer talk about cultural domestication but rather speak of two separate traditions: the Tagorian ba ul and bartama n panth s (cf. Urban, 1999: 15). While the former is responsible of social alignment, the latter engages with resistance in a situation of perpetual asymmetry, the initial and powerful, radical and insoluble form of antagonism within the displacement (Negri, 2003: 43; Verter, 2004: 190). In their manifest willingness to be part of the market, or to embody the marketplace, professional Bauls are adamant about their position. Displacement is not their game, as the resources offered by Empire in the global ba ja r are enough to satisfy their spiritual (re)quest. The twenty-rst century Baul is an aesthetic icon delivering a ready-made spirituality which satises the market. The discourse is no more selective, restricted and inward but exoteric and outward. As Gramsci would have noted, the Bauls see themselves as responding to a request. The product of a superstructural programme, they epitomise a global discourse that, instead of delivering a practical message of deliverance, is designed to advertise a product (Adorno, 2008: 63). Yet at some point, in the heart of Empire, something breaks up and generates alternative forms of resistance that go beyond the spirituality materialism dichotomy. As Marx informs us, the crisis is endemic in the capitalist system in that development depends on the accumulation of capital and the exploitation of resources. Western Bauls incarnate such a crisis. As ba ul-panth s, these radical sa dhaka s (and sa dhika s) strictly adhere to the rules dictated by a dissenting tradition and their teachers. They are exclusivists and in their effort to object to the superstructure and radicalise the body as source of knowledge, they both perform a mysticism featured by indifference (uda s nata ). It is such apathy or passive revolution (Morton, 2007: 74) that ultimately allows materialist panth s to experience the essence of multitude as a non-mystied order where the proliferation of signs implemented by Empire has escaped the crisis and everything gains meaning (Gramsci, 1971, cited in Morton, 2007: 22). Conversely, professional Bauls, entangled in capitalist dynamics, perpetuate a politics of inclusion that along with globalisation is responsible for the fragmentation of signicance until its ultimate obliteration (Virno, 2004: 90). To conclude, I wish to go back to the crisis of presence theorised by de Martino as a key issue in representing socio-political strategies of marketing mysticism. In the case of the bartama n panth s this can be discussed as a matter of alienation, or a practice of

Ferrari: Mystic Rites for Permanent Class Conict

35

indifference. While the experience of professional Bauls epitomises the loss of control of the peoples labour, materialist Bauls, by controlling and administering revolutionary potential, express the radicalism of the multitude as opposed to the society of control. Such a reading reinforces existing discourses on economic marginalisation and political powerlessness as factors that heavily mark the notion of body and experience in the territory. But the world as it is currently represented is, as de Martino (2002: 425) puts it,

also a world of limits, of external paths and resisting bodies that dictate the terms of the possibility, or non-possibility, to utilise the link that through our personal biography, the education we received and [our] acquired skills, connects us to the living society, the chain of generations [and] ultimately to the whole history of man and the universe.

The materialist Bauls presence goes beyond the bodysoul dichotomy and asserts itself by expressing critical power. The capacity to acknowledge the crisis of the system and the potential to object to the global ba ja r is the actual s akti offered by a territorial and oppositional sa dhana leading to afrmation and indifference.

Notes

1. See especially McDaniel (1989), Openshaw (1995, 2002) and Urban (1999, 2001a, 2001b, 2003). 2. Gramsci (1971), quoted in Crehan (2002: 118), italics in the original. 3. These are all considered cooling elements that counterbalance the heat (i.e., power) of the mixture. 4. Not all of the panth s perform this ritual. Some of them purify their bodies by drinking a mixture of milk (ks r r), molasses (gur c), symbolic deectors ), water (n ) and cardamom (ela of the four moons. 5. The initiatory path of Muslim Bauls or phakirs is not very different. Baul phakirs use a Su technical terminology imbued with Arabic and Persian words. However, categories are highly exible and Bauls tend to switch from Hindu to Muslim jargon, paying no attention to the meaning outsiders attribute to words. 6. The nal statement refers to ru per ka j, the extraction of the ova, one of the four works of the ca ricandra sa dhana. The verb chula herein translated to touchis generally used to indicate to peel or to scrape, which is referred to the procedure used by the sa dhika to separate ova from blood. 7. A different exegesis based on Yotin Das Bauls interpretation is given in Capwell (1986: 185). 8. Other professionals are contributing to the spread of the post-Tagorian stereotype, for example, the Baul Bishwa group, Bapi Das Baul, Purna Das son and Paban Das Baul.

References

Adorno, Theodore (2008) The Culture Industry. London and New York: Routledge. Bakhunin, Mikhail (1871) God and the State. Available at http://www.marxists.org/reference/ archive/bakunin/works/godstate/ch01.htm (Accessed 20 November 2011).

South Asia Research Vol. 32 (1): 2138

36

South Asia Research Vol. 32 (1): 2138

Baul, Purna Das & Thielemann, Selina (2003) Baul Philosophy. New Delhi: APH Publishing. Bergunder, Michael (2010) What is Esotericism? Cultural Studies Approaches and the Problem of Denition in Religious Studies, Method and Theory in the Study of Religion, 22(1): 936. Bhattacharya, J.N. (1968) Hindu Castes and Sects. Reprint of 1896 edition. Calcutta: Firma KLM. Bhattacharya, U. (2002 [1408 B.S.]) Ba n gla r Ba ul o Ba ul ga n (The Bauls of Bengal and Baul Songs). Reprint of 1958 [1364 B.S.] edition. Calcutta: Oriental Book Company. Blacker, H. (2001) Enlightenments Divine Jester Mr. Lee Lozowick. Rock n Roll, Crazy Wisdom, and Slavery to the Divine, What is Enlightenment? 20 (Fall-Winter). Available at http://www.enlightennext.org/magazine/j20/lee.asp?page=2 (Accessed 5 April 2010). Capwell, Charles (1986) The Music of the Bauls of Bengal. Kent: Kent State University. Crapanzano, Vincent (2004) Imaginative Horizons. An Essay in Literary-Philosopical Anthropology. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press. Crehan, Kate (2002) Gramsci, Culture and Anthropology. London and Sterling, Virginia: Pluto Press. Crovetto, Helen (2006) Embodied Knowledge and Divinity. The Hohm Community as Western-style Ba uls, Nova Religio, 10(1): 6995. de Martino, Ernesto (1951) Il folklore progressivo. Note lucane (Progressive Folklore. Notes from Lucania), lUnit, 26 June: 3. (1993) Scritti minori su religione, marxismo e psicoanalisi. (Minor Writings on Religion, Marxism and Psychoanalysis). Edited by R. Altamura and P. Ferretti. Roma: Nuove Edizioni Romane. (2002) La ne del mondo. Contributo allanalisi delle apocalissi culturali (The End of the World. A Contribution to the Analysis of Cultural Apocalypses). Torino: Einaudi. Dimock, Edward C. Jr. (1959) Rabindranath Tagore: The Greatest of the Ba uls of Bengal, The Journal of Asian Studies, 19(1): 3351. Foucault, Michel (2007) Madness and Civilization. London and New York: Routledge. Gramsci, Antonio (1971) Selections for Prison Notebooks. Edited by Q. Hoare and G. Nowell Smith. London: Lawrence & Wishart. (2007) Quaderni del carcere (Prison Notebooks). 4 vols. Torino: Einaudi. Hardt, Michael & Negri, Antonio (2000) Empire. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Hanssen, Kristin (2002) Ingesting Menstrual Blood: Notions of Health and Bodily Fluids in Bengal, Ethnology, 41(4): 36579. Helm, Levon (2000) This Wheels on Fire: Levon Helm and the Story of the Band. Chicago: A Cappella Books. (2006) Big Pink Bauls and a Chillum Full of Snake Head. Available at http://magicofjuju. blogspot.com/2006/09/big-pink-bauls-and-chillum-full-of.html (Accessed 1 April 2010). Jha, Shakti Nath (1996) Ca ri-Candra Bhed: Use of the Four Moons. In R.K. Ray (Ed.), Mind, Body and Society. Life and Mentality in Colonial Bengal (pp. 65108). Calcutta: Oxford University Press. Khepa Baul, Lee (1993) Derisive Laughter from a Bad Poet. Prescott: Hohm Press. McDaniel, June (1989) The Madness of the Saints. Ecstatic Religion in Bengal. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Morton, Adam D. (2007) Unravelling Gramsci. Hegemony and Passive Revolution in the Global Economy. London: Pluto Press.

Ferrari: Mystic Rites for Permanent Class Conict

37

Nandy, P. (1999) No one Respects an Artiste. They Think we are Favour Seekers, Parasites. The Rediff Special. New Delhi (20 December). Available at http://www.rediff.com/news/ oct/16nandy.htm (Accessed 20 November 2011). Negri, Antonio (2003) Time for Revolution. London and New York: Continuum. Openshaw, Jeanne (1995) The Radicalism of Tagore and the Ba uls of Bengal: An Indigenous Critique? South Asia Research, 17(1): 2036. (2002) Seeking Ba uls of Bengal. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Sen, Kshiti M. (1952) The Bauls of Bengal, Vishvabharati Quarterly, 18(2): 12347. Sontag, Susan (2009) Styles of Radical Will. London: Penguin. Tagore, Rabindranath (1922) Creative Unity. New York: Macmillan. Urban, Hugh B. (1999) The Politics of Madness: The Construction and Manipulation of the Ba ul Image in Modern Bengal, South Asia, 12(1): 1346. (2001a) The Market Place and the Temple: Economic Metaphors and Religious Meanings in the Folk Songs of Colonial Bengal, The Journal of Asian Studies, 60(4): 1085114. (2001b) The Economics of Ecstasy. Tantra, Secrecy, and Power in Colonial Bengal. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. (2003) Sacred Capital: Pierre Bourdieu and the Study of Religion, Method and Theory in the Study of Religion, 15(4): 35489. (2006) Magia Sexualis. Sex, Magic, and Liberation in Modern Western Esotericism. Berkeley, Los Angeles and London: University of California Press. Verter, B. (2004) Bourdieu and the Ba uls Reconsidered, Method and Theory in the Study of Religion, 16(2): 18292. Virno, Paolo (2004) A Grammar of the Multitude. New York and Los Angeles: Semiotext(e). Zbavitel, Dusan (1961) Rabindranath and the Folk Literature of Bengal, Folklore, 2(1), 214.

Dr Fabrizio M. Ferrari was educated in Indology at the Ca Foscari University of Venice (Italy) and received his PhD from SOAS in 2005 for a study on popular Hinduism in West Bengal. He taught South Asian Religions and Religious Studies at SOAS and now, as a senior lecturer in the Study of Religion at the University of Chester, specialises in the study of South Asian popular Hinduism and folklore. He has published articles and book chapters on Hinduism, with particular reference to village disease goddesses and healing rituals. His rst book is on the Bauls of Bengal (Oltre il conne, dove la terra rossa. Canti damore e destasi dei baul del Bengala, Milan: Ariele, 2001), while his new work discusses the gajan festival of Bengal (Guilty Males and Proud Females. Negotiating Genders in a Bengali Festival, Kolkata: Seagull, 2010). He is presently nalising the rst monograph in English on the Italian anthropologist and historian of religion Ernesto de Martino (Ernesto de Martino on Religion. The Crisis and the Presence, London and Oackville: Equinox, forthcoming 2011) and has edited the volume on Health and Religious Rituals in South Asia: Disease, Possession and Healing (New York and London: Routledge, 2011). His research is now mainly directed towards the study of religious folklore and ritual in the framework of cultural studies and radical theory. His forthcoming books are Charming Beauties and Frightful Beasts. Non-human Animals in South Asian Myth, Ritual and Folklore (co-edited with Thomas

South Asia Research Vol. 32 (1): 2138

38

South Asia Research Vol. 32 (1): 2138

Dhnhardt, London and Oackville: Equinox, forthcoming 2013) and Religion and Medicine in Hindu Folklore. The Goddess S tala and Ritual Healing in North India (London and New York: Continuum, forthcoming 2014). Address: Department of Theology and Religious Studies, University of Chester, Parkgate Road, Chester CH1 4BJ, UK. [e-mail: f.ferrari@chester.ac.uk]

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- How to Know: Spirit Music - Crazy Wisdom, Shamanism And Trips to The Black SkyDari EverandHow to Know: Spirit Music - Crazy Wisdom, Shamanism And Trips to The Black SkyBelum ada peringkat

- Medical Culture of The People of NavajoDokumen13 halamanMedical Culture of The People of NavajoSamBelum ada peringkat

- Prayers To Our Lady of GuadalupeDokumen8 halamanPrayers To Our Lady of GuadalupeOliver356Belum ada peringkat

- UTS Midterm SlideDokumen47 halamanUTS Midterm SlideArmySapphireBelum ada peringkat

- Carl JungDokumen2 halamanCarl JungNameah MagomnangBelum ada peringkat

- Plastic ShamanDokumen4 halamanPlastic ShamanroberthertzBelum ada peringkat

- Horseback Consecration RitualDokumen21 halamanHorseback Consecration RitualDhamma_StorehouseBelum ada peringkat

- The Safety Practices in The Chemistry Laboratories of Higher Secondary Schools of Samtse District: A Case Study in BhutanDokumen15 halamanThe Safety Practices in The Chemistry Laboratories of Higher Secondary Schools of Samtse District: A Case Study in BhutanMamta AgarwalBelum ada peringkat

- 2007 Pfaffenberger - Eploring Pathways To Postconventional Ego DevelopmentDokumen159 halaman2007 Pfaffenberger - Eploring Pathways To Postconventional Ego DevelopmentAnssi BalkBelum ada peringkat

- BERARDINI, Sergio Fabio, 2015, Indeterminacy and Ritual Symbol. Philosophical Remarks On Ernesto de Martino's The Land of RemorseDokumen17 halamanBERARDINI, Sergio Fabio, 2015, Indeterminacy and Ritual Symbol. Philosophical Remarks On Ernesto de Martino's The Land of RemorseLobo MauBelum ada peringkat

- Ayahuasca and Spiritual Crisis sPACE FOR PERSONAL GROWTH PDFDokumen25 halamanAyahuasca and Spiritual Crisis sPACE FOR PERSONAL GROWTH PDF19simon85Belum ada peringkat

- The Concept of Spiritual Power in East Asian and Canadian Aboriginal Thought (Social Compass) (2017)Dokumen12 halamanThe Concept of Spiritual Power in East Asian and Canadian Aboriginal Thought (Social Compass) (2017)jk100% (1)

- Ibogaine Udi BastiaansDokumen27 halamanIbogaine Udi BastiaansBrianBelum ada peringkat

- The H Ózhó Way by Noelle JohnDokumen3 halamanThe H Ózhó Way by Noelle Johnapi-341711989Belum ada peringkat

- Spinoza and Deep EcologyDokumen25 halamanSpinoza and Deep EcologyAnne FremauxBelum ada peringkat

- The Changing of Diné WomenDokumen9 halamanThe Changing of Diné Womenapi-385626757Belum ada peringkat

- Carl JungDokumen5 halamanCarl JungSanu Joseph100% (1)

- Shamanism Global Summit 2017 SurveyDokumen12 halamanShamanism Global Summit 2017 SurveyferezleturBelum ada peringkat

- Navajo ChantsDokumen4 halamanNavajo ChantsAlejandro SerraBelum ada peringkat

- Dale Pendell - A Raven in The DojoDokumen6 halamanDale Pendell - A Raven in The Dojogalaxy5111Belum ada peringkat

- The Iron PentacleDokumen6 halamanThe Iron PentaclecmarigBelum ada peringkat

- Web of Life5b - Human WeaknessDokumen3 halamanWeb of Life5b - Human WeaknessJohn DavidsonBelum ada peringkat

- The Bear Feast ManualDokumen56 halamanThe Bear Feast ManualCorwen BrochBelum ada peringkat

- In Darkness and Secrecy The Anthropology of Sorcery and Witchcraft in Amazonia - Neil L Whitehead Amp Amp Robin Wright PDFDokumen394 halamanIn Darkness and Secrecy The Anthropology of Sorcery and Witchcraft in Amazonia - Neil L Whitehead Amp Amp Robin Wright PDFBree ArulpragasamBelum ada peringkat

- Long-Term Effects of Psychedeli - Jacob S. AdayDokumen11 halamanLong-Term Effects of Psychedeli - Jacob S. AdaysilentrevoBelum ada peringkat

- Ayahuasca Ritual Religion Brazil 2010Dokumen5 halamanAyahuasca Ritual Religion Brazil 2010jrvoivod4261Belum ada peringkat

- Ann Ulanov - Review Leaving My Fathers House A Journey To Conscious Femininity by Marion WoodmanDokumen4 halamanAnn Ulanov - Review Leaving My Fathers House A Journey To Conscious Femininity by Marion WoodmanNorahBelum ada peringkat

- Commemorative Motifs, Mourning Images, and Memento MoriDokumen7 halamanCommemorative Motifs, Mourning Images, and Memento MoritentusajaBelum ada peringkat

- Culture in A Netbag (M. StrathernDokumen25 halamanCulture in A Netbag (M. StrathernEduardo Soares NunesBelum ada peringkat

- Touching The Divine - Recent Research On Neo-Paganism and Neo-ShamanismDokumen16 halamanTouching The Divine - Recent Research On Neo-Paganism and Neo-ShamanismAndres PuentesBelum ada peringkat

- Web of Life7 - Up To The EyesDokumen3 halamanWeb of Life7 - Up To The EyesJohn DavidsonBelum ada peringkat

- PGM Phonetic Pronunciation Guide 459-89Dokumen2 halamanPGM Phonetic Pronunciation Guide 459-89Soror BabalonBelum ada peringkat

- Ayahuasca and The Grotesque Body Stephan BeyerDokumen2 halamanAyahuasca and The Grotesque Body Stephan Beyerckaplan07Belum ada peringkat

- When The Gods Drank Urine: Psychedelic Insights SurveyDokumen13 halamanWhen The Gods Drank Urine: Psychedelic Insights Surveykuka100% (1)

- Anthony Oliveira - One Devil Too ManyDokumen23 halamanAnthony Oliveira - One Devil Too Manygalaxy5111Belum ada peringkat

- ARCHAEBACTERIA & EUBACTERIA-Group 1Dokumen38 halamanARCHAEBACTERIA & EUBACTERIA-Group 1Nur AfiahBelum ada peringkat

- Ibogaine For PTSDDokumen8 halamanIbogaine For PTSDAlan Jules WebermanBelum ada peringkat

- Soul Farm - The Shamans Meet AgainDokumen3 halamanSoul Farm - The Shamans Meet AgainDwarika Prasad VidyarthyBelum ada peringkat

- Shamanism in Philippines, Manipur and Korea: A Comparative StudyDokumen19 halamanShamanism in Philippines, Manipur and Korea: A Comparative StudyJames Albert Narvaez100% (1)

- 00 Zohar Introduction by Daniel MattDokumen11 halaman00 Zohar Introduction by Daniel MattpilgrimBelum ada peringkat

- Antidepressant Potentials of Aqueous Extract of Voacanga Africana Stept. Ex Eliot (Apocynaceae) Stem BarkDokumen7 halamanAntidepressant Potentials of Aqueous Extract of Voacanga Africana Stept. Ex Eliot (Apocynaceae) Stem BarkT. A OwolabiBelum ada peringkat

- Hessayon, A. 'Translating Jacob Boehme'Dokumen38 halamanHessayon, A. 'Translating Jacob Boehme'Ariel Hessayon100% (1)

- Healing Journey Chap 5 Ibogaine Fantasy and RealityDokumen55 halamanHealing Journey Chap 5 Ibogaine Fantasy and RealitychantitaBelum ada peringkat

- Shamanism and Altered States of ConsciousnessDokumen15 halamanShamanism and Altered States of Consciousnessyodoid100% (2)

- How To Join Your State Militia To Save AmericaDokumen14 halamanHow To Join Your State Militia To Save AmericaLizBelum ada peringkat

- Gaule The Mag Astro Mancer 1652 CompleteDokumen426 halamanGaule The Mag Astro Mancer 1652 Completemayella01Belum ada peringkat

- Formulation and Evaluation of Benzyl Benzoate EmulgelDokumen4 halamanFormulation and Evaluation of Benzyl Benzoate EmulgelIOSRjournalBelum ada peringkat

- Soteria (Salvation)Dokumen2 halamanSoteria (Salvation)John UebersaxBelum ada peringkat

- Aboriginal BeliefsDokumen2 halamanAboriginal Beliefsapi-289036157100% (1)

- Kulam-Philippine - Anthony ViveroDokumen2 halamanKulam-Philippine - Anthony ViveroJungOccult100% (1)

- Roderick Main - Magic and Science in The Modern Western Tradition of The I ChingDokumen14 halamanRoderick Main - Magic and Science in The Modern Western Tradition of The I ChingKenneth AndersonBelum ada peringkat

- Annie Besant - in The Outer Court PDFDokumen172 halamanAnnie Besant - in The Outer Court PDFMichael NolleyBelum ada peringkat

- HONOS ASSESSMENT (Health of The Nation Outcome Scales)Dokumen5 halamanHONOS ASSESSMENT (Health of The Nation Outcome Scales)SNBelum ada peringkat

- Anaconda Cosmica Invitation EnglishDokumen4 halamanAnaconda Cosmica Invitation EnglishGuro Straumsheim GrønliBelum ada peringkat

- Adolescent Sexuality College of OrgonomyDokumen93 halamanAdolescent Sexuality College of OrgonomykittyandtrinityBelum ada peringkat

- Cadena de AmorDokumen1 halamanCadena de AmorIsrael R OmegaBelum ada peringkat

- Archetypes in The Cosmogonic Myths PDFDokumen9 halamanArchetypes in The Cosmogonic Myths PDFOscar Gordon WongBelum ada peringkat

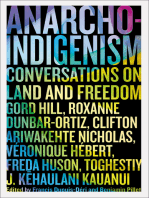

- Anarcho-Indigenism: Conversations on Land and FreedomDari EverandAnarcho-Indigenism: Conversations on Land and FreedomBelum ada peringkat

- Golden Ages, Dark Ages: Imagining the Past in Anthropology and HistoryDari EverandGolden Ages, Dark Ages: Imagining the Past in Anthropology and HistoryBelum ada peringkat

- How About Demons?: Possession and Exorcism in the Modern WorldDari EverandHow About Demons?: Possession and Exorcism in the Modern WorldPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (6)

- Heart Inventory-Reactive CycleDokumen6 halamanHeart Inventory-Reactive CyclesandanandaBelum ada peringkat

- Spp153 MarijuanaDokumen20 halamanSpp153 MarijuanasandanandaBelum ada peringkat

- Cannabis Chassidis Book by Yoseph Needelman PDFDokumen399 halamanCannabis Chassidis Book by Yoseph Needelman PDFAlex Mostro LosAngeles0% (1)

- KRIYAYOGADokumen2 halamanKRIYAYOGAsandanandaBelum ada peringkat

- Nity An and A Pranayam ADokumen1 halamanNity An and A Pranayam AsandanandaBelum ada peringkat

- English IIDokumen63 halamanEnglish IIsandanandaBelum ada peringkat

- Modern Yoga Masters Lineage TreeDokumen7 halamanModern Yoga Masters Lineage TreeVandamme NeoBelum ada peringkat

- Cannabis Chassidis Book by Yoseph Needelman PDFDokumen399 halamanCannabis Chassidis Book by Yoseph Needelman PDFAlex Mostro LosAngeles0% (1)

- How Yoga Works? (Possible Mechanisms)Dokumen11 halamanHow Yoga Works? (Possible Mechanisms)sandanandaBelum ada peringkat

- Advanced HathayogaDokumen9 halamanAdvanced HathayogasandanandaBelum ada peringkat

- The Original Teachings of Yoga From Patanjali Back To HiranyagarbhaDokumen5 halamanThe Original Teachings of Yoga From Patanjali Back To HiranyagarbhasandanandaBelum ada peringkat

- Phil Hine - Tantrum MagickDokumen4 halamanPhil Hine - Tantrum MagickMihai BuşeBelum ada peringkat

- Fascism HomosexualityDokumen12 halamanFascism Homosexualitysandananda100% (2)

- Cannabis Chassidis Book by Yoseph Needelman PDFDokumen399 halamanCannabis Chassidis Book by Yoseph Needelman PDFAlex Mostro LosAngeles0% (1)

- TheScribe 6Dokumen50 halamanTheScribe 6sandanandaBelum ada peringkat

- 2711 5176 1 PBDokumen30 halaman2711 5176 1 PBsandanandaBelum ada peringkat

- 2711 5176 1 PBDokumen30 halaman2711 5176 1 PBsandanandaBelum ada peringkat

- Spp153 MarijuanaDokumen20 halamanSpp153 MarijuanasandanandaBelum ada peringkat

- Book 1Dokumen7 halamanBook 1sandanandaBelum ada peringkat

- Saundaryalahari PDFDokumen32 halamanSaundaryalahari PDFVastu VijayBelum ada peringkat

- How Yoga Works? (Possible Mechanisms)Dokumen11 halamanHow Yoga Works? (Possible Mechanisms)sandanandaBelum ada peringkat

- Gene of IsisDokumen53 halamanGene of IsisLeia Little100% (1)

- Sounds of The DharmaDokumen36 halamanSounds of The DharmaJoseph HayesBelum ada peringkat

- 8946 FD 01Dokumen1 halaman8946 FD 01sandanandaBelum ada peringkat

- Arya Tara PujaDokumen8 halamanArya Tara PujasandanandaBelum ada peringkat

- Surya Namaskar (Sun Salutations Postures)Dokumen5 halamanSurya Namaskar (Sun Salutations Postures)sandanandaBelum ada peringkat

- 4complete The Min1Dokumen3 halaman4complete The Min1julia merlo vegaBelum ada peringkat

- Emotions Influence Color Preference PDFDokumen48 halamanEmotions Influence Color Preference PDFfllorinvBelum ada peringkat

- Shipping Operation Diagram: 120' (EVERY 30')Dokumen10 halamanShipping Operation Diagram: 120' (EVERY 30')Hafid AriBelum ada peringkat

- Case Study 2022 - HeyJobsDokumen6 halamanCase Study 2022 - HeyJobsericka.rolim8715Belum ada peringkat

- Brent Berlin-Covert Categories and Folk TaxonomyDokumen10 halamanBrent Berlin-Covert Categories and Folk TaxonomyKawita ChuachengBelum ada peringkat

- LP.-Habitat-of-Animals Lesson PlanDokumen4 halamanLP.-Habitat-of-Animals Lesson PlanL LawlietBelum ada peringkat

- Christian Education of Zendeling-Based at The Kalimantan Evangelical Church (GKE)Dokumen16 halamanChristian Education of Zendeling-Based at The Kalimantan Evangelical Church (GKE)Editor IjrssBelum ada peringkat

- Kravitz Et Al (2010)Dokumen5 halamanKravitz Et Al (2010)hsayBelum ada peringkat

- Rulings On MarriageDokumen17 halamanRulings On MarriageMOHAMED HAFIZ VYBelum ada peringkat

- TSH TestDokumen5 halamanTSH TestdenalynBelum ada peringkat

- Short Tutorial On Recurrence RelationsDokumen13 halamanShort Tutorial On Recurrence RelationsAbdulfattah HusseinBelum ada peringkat

- Jujutsu Kaisen, Volume 23, Chapter 225 - The Decesive Battle (3) - Jujutsu Kaisen Manga OnlineDokumen20 halamanJujutsu Kaisen, Volume 23, Chapter 225 - The Decesive Battle (3) - Jujutsu Kaisen Manga OnlinemarileyserBelum ada peringkat

- Speech VP SaraDokumen2 halamanSpeech VP SaraStephanie Dawn MagallanesBelum ada peringkat

- Info Cad Engb FestoDokumen14 halamanInfo Cad Engb FestoBayu RahmansyahBelum ada peringkat

- Utsourcing) Is A Business: Atty. Paciano F. Fallar Jr. SSCR-College of Law Some Notes OnDokumen9 halamanUtsourcing) Is A Business: Atty. Paciano F. Fallar Jr. SSCR-College of Law Some Notes OnOmar sarmiento100% (1)

- BuildingBotWithWatson PDFDokumen248 halamanBuildingBotWithWatson PDFjavaarchBelum ada peringkat

- Law On Common Carriers: Laws Regulating Transportation CompaniesDokumen3 halamanLaw On Common Carriers: Laws Regulating Transportation CompaniesLenoel Nayrb Urquia Cosmiano100% (1)

- Machine DesignDokumen34 halamanMachine DesignMohammed Yunus33% (3)

- Portfolio Artifact 1 - Personal Cultural Project Edu 280Dokumen10 halamanPortfolio Artifact 1 - Personal Cultural Project Edu 280api-313833593Belum ada peringkat

- EntropyDokumen38 halamanEntropyPreshanth_Jaga_2224Belum ada peringkat

- CPARDokumen9 halamanCPARPearl Richmond LayugBelum ada peringkat

- What Is A Business IdeaDokumen9 halamanWhat Is A Business IdeaJhay CorpuzBelum ada peringkat

- USA V Rowland - Opposition To Motion To End Probation EarlyDokumen12 halamanUSA V Rowland - Opposition To Motion To End Probation EarlyFOX 61 WebstaffBelum ada peringkat

- Energizing Your ScalesDokumen3 halamanEnergizing Your ScalesjohnBelum ada peringkat

- E-Gift Shopper - Proposal - TemplateDokumen67 halamanE-Gift Shopper - Proposal - TemplatetatsuBelum ada peringkat

- Exercise Reported SpeechDokumen3 halamanExercise Reported Speechapi-241242931Belum ada peringkat

- Brand Zara GAP Forever 21 Mango H&M: Brand Study of Zara Nancys Sharma FD Bdes Batch 2 Sem 8 Brand-ZaraDokumen2 halamanBrand Zara GAP Forever 21 Mango H&M: Brand Study of Zara Nancys Sharma FD Bdes Batch 2 Sem 8 Brand-ZaraNancy SharmaBelum ada peringkat

- SakalDokumen33 halamanSakalKaran AsnaniBelum ada peringkat

- 1.Gdpr - Preparation Planning GanttDokumen6 halaman1.Gdpr - Preparation Planning GanttbeskiBelum ada peringkat

- The Intelligent Investor NotesDokumen19 halamanThe Intelligent Investor NotesJack Jacinto100% (6)