Psychiatric Manifestations of Neurosyphilis

Diunggah oleh

Drashua AshuaDeskripsi Asli:

Judul Asli

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Psychiatric Manifestations of Neurosyphilis

Diunggah oleh

Drashua AshuaHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Unusual Case Report

Three Cases of Psychiatric Manifestations of Neurosyphilis

Tanveer Sobhan, M.D., M.P.H. Heather M. Rowe, M.D. William G. Ryan, M.D. Cesar Munoz, M.D.

Along with the advent of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) came a worldwide resurgence of syphilis. The later stages of syphilis, especially neurosyphilis, may present with symptoms of virtually any psychiatric disorder. The authors present three cases of neurosyphilis diagnosed at the Center for Psychiatric Medicine of the University of Alabama at Birmingham, where the patients presented with overwhelmingly psychiatric manifestations. The authors recommend that clinicians have a high index of suspicion of neurosyphilis, which may have an exclusively psychiatric presentation. (Psychiatric Services 55:830832, 2004)

ium, and dementia (2). Here we report three cases of neurosyphilis among persons who presented as psychiatric patients during a fouryear period at the Center for Psychiatric Medicine of the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

Psychiatric manifestations of neurosyphilis

A review of the literature indicates various psychiatric presentations of neurosyphilis (3). A significant number of patients with neurosyphilis present with dementia, which has an insidious onset leading to a progressive global deterioration in intellectual functioning, with episodes of delirium. Lesions in the temporoparietal lobes among patients with neurosyphilis have a significant correlation with low scores on the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) (4). About 27 percent of patients with general paresis present with depression characterized by psychomotor retardation, melancholia, and suicidal ideation. Mania may also be present, characterized by euphoria, irritability, grandiosity, delusions, loose associations, rambling and pressured speech, flight of ideas, incoherence, and hyperactivity (5). Another manifestation of neurosyphilis is psychosis, which can be indistinguishable from psychotic features of schizophrenia with acute or insidious onset. Lesions in the frontal lobes seen among patients with neurosyphilis correlate with high scores on the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) (4). Patients may also present with altered personality, which is characterized by antisocial behavior, explosive

PSYCHIATRIC SERVICES

temper, hostility, emotional lability, affective instability, anhedonia, social withdrawal, decreased attention to personal affairs, unusual giddiness, histrionicity, and hypersexuality (2). Substance-related presentations are also seen among patients with neurosyphilis, including excessive drinking of alcohol, low tolerance of alcohol, and features suggestive of Korsakoffs psychosis. Another manifestation is sexual dysfunction: impotence has been reported in tabetic neurosyphilis. Finally, a diagnosis of neurosyphilis must be considered when possible causes of delirium are excluded, which often heralds the acute onset of general paresis.

Case reports

Mr. A, a 45-year-old African-American man with no psychiatric history, was admitted to the Center for Psychiatric Medicine of the University of Alabama at Birmingham with violent behavior and hyperreligiosity and for striking staff members at a residential substance abuse treatment facility. His physical and neurologic test results were normal. Laboratory investigation and a urine drug screen were negative, as were tests for HIV antibodies. A computed tomography scan of the brain showed enlargement of the third and lateral ventricles with some sulcal widening. The results of Mr. As serum and cerebrospinal fluid serologic tests for syphilis are presented in Table 1, along with those of the other patients whose cases are reported here. Interestingly, Mr. As CSF protein, glucose, and cell counts were within the normal range, which, al-

long with the spread of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) there has been a worldwide resurgence of syphilis (1). Neurosyphilis may present as virtually any psychiatric disorder, including personality disorder, psychosis, delir-

Dr. Sobhan is affiliated with the department of psychiatry of Faith Regional Health Services, 1500 Koenigstein Avenue, Suite 400, Norfolk, Nebraska 68701 (e-mail, tsobhanmd@yahoo.com). Dr. Rowe is with the department of psychiatry of Greil State Psychiatric Hospital in Montgomery, Alabama. Dr. Ryan is with the department of psychiatry of the University of Alabama in Birmingham. Dr. Munoz is with the department of psychiatry of the Birmingham Department of Veterans Affairs Hospital in Birmingham, Alabama.

830

http://ps.psychiatryonline.org July 2004 Vol. 55 No. 7

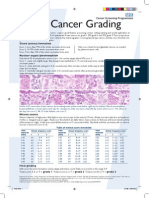

Table 1

Laboratory and neuroimaging test results for three patients with neurosyphilis

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) Venereal disease Serum rapid research plasma regain laboratory 1:32 1:4 White blood cells 2 Red blood cells 7

Patient A

Protein 38

Glucose 68

MMSEa Brain (repeat) imaging 22 Enlarged ventricles Frontal lobe hyperintensity Frontotemporal atrophy, enlarged lateral

Other Serum positive FTA-ABSb; negative HIV; normal EEGc Normal EEG; negative HIV Serum TPHAd reactive; negative HIV; no growth in CSF culture

B C

1:128 1:128

1:16 1:16

57 66

71 81

40 13

13 3

20 (27) 16 (23)

a b c d

Mini-Mental State Examination Fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption assay Electroencephalogram Treponema pallidum haemagglutination assay

though unusual, can occur in the late stages of syphilis (6). The patients affect, speech, behavior control, and thought processes all improved soon after initiation of treatment with intramuscular procaine penicillin, although his Folsteins MMSE score remained at 22. (Possible scores range from 0 to 30, with lower scores indicating greater impairment.) Mr. B, a 40-year-old African-American man with no psychiatric or medical history, was brought to the universitys psychiatric emergency department after paramedics found him lying in the street playing dead. He stated that he had had no problems until three months ago, when he felt guilty about an affair he had had with a woman at his church and started to believe that he was being punished by God for sinning. He thought people were trying to harm him and to poison his food and water with PineSol cleaning liquid. He was admitted to the universitys psychiatric emergency department because of paranoid delusions. The patient reported no auditory or visual hallucinations. His MMSE score on admission was 20. The results of his physical and neurologic examinations were normal, and his laboratory tests and urine drug screen were negative, as were tests for HIV antibodies. Cranial MRI showed small flare hyperintensities in the left

PSYCHIATRIC SERVICES

and right frontal white matter. The infectious diseases department was consulted, and the patient improved remarkably after treatment with intravenous penicillin. A repeat MMSE yielded a score of 27. Mr. C, a 51-year-old white man, was brought to the university involuntarily because of personality changes and bizarre behavior. He had worked for many years as a construction worker but had lost interest in his job and had quit about six months earlier. He would wander the highways picking up trash. He became increasingly more apathetic and uncommunicative. He would often refuse to change his clothes, bathe, or maintain even minimal hygiene. He had recently become incontinent. His physical examination results were normal except for neurologic tests, which showed a wide-based gait with 4+ deep tendon reflexes of biceps, triceps, brachioradialis, and patellar. Inspection of the penis revealed two circular areas of hyperpigmentation. Tests for HIV antibodies were negative. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain showed deep atrophy with symmetric enlargement of the lateral ventricles. Approximately five days into treatment with ceftriaxone, the patient began to show increased interaction, improved mood, better personal hygiene, and goal-directed speech. Approximately ten days into treatment

he started to regain continence, although he had occasional relapses. A repeat MMSE yielded a score of 23.

Discussion

The three patients described here presented with multitudes of psychiatric signs and symptoms. Patients with neurosyphilis can also present with many different physical or neurologic symptoms that lead to admission or follow-up at a medical or neurology unit. What was interesting about the three cases discussed here was that all patients showed exclusively psychiatric manifestations, leading to direct admission to a psychiatric unit rather than a medical or neurology unit with psychiatric consultation. The point we are trying to emphasize here is that cliniciansincluding internists and neurologists, and especially psychiatristsneed to have a high index of suspicion of neurosyphilis, which may have an exclusively psychiatric presentation rather than medical or neurologic symptoms, because, despite a dramatic decline in the incidence of neurosyphilis since the early 20th century, new cases are still occurring. Without such an awareness on the part of clinicians, not only will this diagnosis be missed, but an extensive and unnecessary laboratory investigationand its associated tremendous costswill follow.

831

http://ps.psychiatryonline.org July 2004 Vol. 55 No. 7

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Preventions guidelines for laboratory diagnosis of neurosyphilis (7), all three of the patients reported here had neurosyphilis. Results of the patients brain imaging studies, including enlarged third and lateral ventricles and frontal and temporal lobe atrophy, are also consistent with findings of other investigators (8). Cortical atrophy also explains the low MMSE scores of the three patients and again is a finding consistent with those of other investigators (8). All three patients improved after antibiotic therapy. It is noteworthy that all these patients were HIV negative. The natural history of neurosyphilis can be altered by concurrent HIV infection (9). Interpretation of serologic test results can also be confusing, because patients with both HIV and syphilis have higher titers on nontreponemal tests than do patients with syphilis alone (10). Because the clinical presentations of the three patients were not clouded or compounded by concurrent HIV infection, we can strong-

ly argue that patients with neurosyphilis can present with predominantly psychiatric symptoms. We recommend that a diagnosis of neurosyphilis be considered among patients who have unusual psychiatric symptoms and that the HIV status of all such patients be checked.

ifestations of neurosyphilis. South African Medical Journal 82:335337, 1992 3. Scheck DN, Hook EW III: Neurosyphilis. Medical Clinics of North America 8:769 795, 1994 4. Kodama K, Okada SI, Komatsu N, et al: Relationship between MRI findings and prognosis for patients with general paresis. Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience 2:246250, 2000 5. Hoffman BF: Reversible neurosyphilis presenting as chronic mania. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 43:338339, 1982 6. Jacobs RA: Infectious diseases: spirochetal, in Current Medical Diagnosis and Treatment, 40th ed. Edited by Tierney LM, McPhee SJ, Papadakis MA. New York, Lange Medical Books, 2001 7. Luger AF, Schmidt BL, Kaulich M: Significance of laboratory findings for the diagnosis of neurosyphilis. International Journal of STD and AIDS 11:224234, 2000 8. Gliatto MF, Caroff SN: Neurosyphilis: a history and clinical review. Psychiatric Annals 31:153161, 2001 9. Flood JM, Weinstock HS, Guroy ME, et al: Neurosyphilis during the AIDS epidemic, San Francisco, 19851992. Journal of Infectious Disease 177:931940, 1998 10. Hook EW III: Syphilis, in Infections of the Central Nervous System, 2nd ed. Edited by Scheld WM, Whitley RJ, Durack DT. Philadelphia, Lippincott-Raven, 1997

Conclusions

Clinicians, especially psychiatrists, need to remain aware of the clinical presentation, diagnosis, and treatment of neurosyphilis, because many patients with neurosyphilis present with subtle personality changes, dementia, or delirium, which creates a diagnostic dilemma. Therefore, serologic tests for syphilis should be a routine part of the evaluation of patients who present with neuropsychiatric symptoms. References

1. Russouw HG, Roberts MC, Emsley RA, et al: Psychiatric manifestations and magnetic resonance imaging in HIV-negative neurosyphilis. Biological Psychiatry 41:467 473, 1997 2. Roberts MC, Emsley RA: Psychiatric man-

Psychiatric Services Invites Submissions By, About, and For Residents and Fellows

To improve psychiatric training, to highlight the academic work of psychiatric residents and fellows, and to encourage research on psychiatric services by trainees in psychiatry, Psychiatric Services has introduced a continuing series of articles by, about, and for trainees. Submissions should address issues in residency education. They may also report research conducted by residents on the provision of psychiatric services. Joshua L. Roffman, M.D., is the editor of this series. Prospective authorscurrent residents, fellows, and faculty membersshould contact Dr. Roffman at the Wang Ambulatory Care Center 812, Massachusetts General Hospital, 15 Parkman Street, Boston, Massachusetts 02114, e-mail, jroffman@partners.org. All submissions will be peer reviewed, and accepted papers will be highlighted. For information about formatting and submission, visit the journals Web site at http://ps.psychiatryonline.org. Click on the cover of Psychiatric Services and scroll down to Information for Authors.

832

PSYCHIATRIC SERVICES

http://ps.psychiatryonline.org July 2004 Vol. 55 No. 7

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- The Successful Treatment of DisinhibitioDokumen4 halamanThe Successful Treatment of DisinhibitioVicky NotesBelum ada peringkat

- Schizoaffective Disorder: Continuing Education ActivityDokumen10 halamanSchizoaffective Disorder: Continuing Education ActivitymusdalifahBelum ada peringkat

- Literature Review SchizophreniaDokumen5 halamanLiterature Review Schizophreniaafmzuiffugjdff100% (1)

- Esquizofrenia InglesDokumen5 halamanEsquizofrenia Ingleseve-16Belum ada peringkat

- Dementia Due To NeurosyphilisDokumen3 halamanDementia Due To NeurosyphilisIOSRjournalBelum ada peringkat

- Understanding Schizophrenia Through a Case StudyDokumen22 halamanUnderstanding Schizophrenia Through a Case StudyAinal MardhiyyahBelum ada peringkat

- LIDZ THEODORE - A Psicosocial Orientation To Schizophrenic DisordersDokumen9 halamanLIDZ THEODORE - A Psicosocial Orientation To Schizophrenic DisordersRodrigo G.Belum ada peringkat

- SchizophreniaDokumen21 halamanSchizophreniapriya hemBelum ada peringkat

- Overview and Treatment Option: SkizofreniaDokumen8 halamanOverview and Treatment Option: SkizofreniaEvi LoBelum ada peringkat

- Major Self-Mutilation in The First Episode of PsychosisDokumen10 halamanMajor Self-Mutilation in The First Episode of PsychosisJulián EspinalBelum ada peringkat

- Van Os J, Kapur S. Schizophrenia - Lancet 2009 374 635-45 PDFDokumen11 halamanVan Os J, Kapur S. Schizophrenia - Lancet 2009 374 635-45 PDFVictorVeroneseBelum ada peringkat

- Neuropsychiatric Sequelae of Nipah Virus Encephalitis: MethodsDokumen5 halamanNeuropsychiatric Sequelae of Nipah Virus Encephalitis: MethodsTryas YulithaBelum ada peringkat

- Vol 54 No 2 Patel Selby YekkiralaDokumen5 halamanVol 54 No 2 Patel Selby YekkiralaDrashua AshuaBelum ada peringkat

- Refining CBT for Persistent Positive Symptoms in PsychosisDokumen8 halamanRefining CBT for Persistent Positive Symptoms in PsychosisvinodksahuBelum ada peringkat

- Schizophrenia etiology, symptoms, treatmentDokumen12 halamanSchizophrenia etiology, symptoms, treatmentmustafa566512345Belum ada peringkat

- Schizophrenia Patients' Cognition vs. Healthy IndividualsDokumen6 halamanSchizophrenia Patients' Cognition vs. Healthy IndividualsAsti DwiningsihBelum ada peringkat

- 5ch Izoph Ren Ia: Key ConceptsDokumen24 halaman5ch Izoph Ren Ia: Key ConceptsNAURA ARNEITA AN-NAJLABelum ada peringkat

- Psychotic Symptoms As A Continuum Between Normality and PathologyDokumen12 halamanPsychotic Symptoms As A Continuum Between Normality and PathologyOana OrosBelum ada peringkat

- Schizophr Bull 2011 Simonsen 73 83Dokumen11 halamanSchizophr Bull 2011 Simonsen 73 83Tara WandhitaBelum ada peringkat

- CJP May 06 Chaudhari OR7Dokumen8 halamanCJP May 06 Chaudhari OR7haddig8Belum ada peringkat

- Genetics, Cognition, and Neurobiology of Schizotypal Personality: A Review of The Overlap With SchizophreniaDokumen16 halamanGenetics, Cognition, and Neurobiology of Schizotypal Personality: A Review of The Overlap With SchizophreniaDewi NofiantiBelum ada peringkat

- Schizophrenia: Clinical ReviewDokumen5 halamanSchizophrenia: Clinical ReviewPuji Arifianti RamadhanyBelum ada peringkat

- Psychiatric Disorders Associated With EpilepsyDokumen18 halamanPsychiatric Disorders Associated With EpilepsyAllan DiasBelum ada peringkat

- SCHIZOPHRENIFORMDokumen5 halamanSCHIZOPHRENIFORMThrift AdvisoryBelum ada peringkat

- A Talking Cure For PsychosisDokumen6 halamanA Talking Cure For PsychosisKarla ValderramaBelum ada peringkat

- New-Onset: Hallucinations Patients Infected WithDokumen6 halamanNew-Onset: Hallucinations Patients Infected Withtugba1234Belum ada peringkat

- Swinkels PscychopathologieDokumen16 halamanSwinkels PscychopathologiesezalwickBelum ada peringkat

- Bipolaridade e Esclerose MúltiplaDokumen4 halamanBipolaridade e Esclerose MúltiplaLucasFelipeRibeiroBelum ada peringkat

- Psychiatric effects of thyroid hormone disturbanceDokumen9 halamanPsychiatric effects of thyroid hormone disturbanceJosetta WhitneyBelum ada peringkat

- Steroid-Induced PsychosisDokumen2 halamanSteroid-Induced Psychosisanisha batraBelum ada peringkat

- Schizophrenia JAUHAR Publishedonline28January2022 GREEN AAMDokumen44 halamanSchizophrenia JAUHAR Publishedonline28January2022 GREEN AAMAlondra CastilloBelum ada peringkat

- Psychobiology Schizophrenia Research Paper FINAL (At)Dokumen8 halamanPsychobiology Schizophrenia Research Paper FINAL (At)gucci maneBelum ada peringkat

- Neurosyphilis: The Reemergence of An Historical DiseaseDokumen2 halamanNeurosyphilis: The Reemergence of An Historical DiseaseDrashua AshuaBelum ada peringkat

- Case Study LnaDokumen13 halamanCase Study LnaSarah Y AL-SalahatBelum ada peringkat

- Neurotransmitters and SuicideDokumen24 halamanNeurotransmitters and Suicide9rvvgf5vx8Belum ada peringkat

- Roberts Psychiatric 1992Dokumen3 halamanRoberts Psychiatric 1992Drashua AshuaBelum ada peringkat

- Kazkas Su Alcohol PDFDokumen5 halamanKazkas Su Alcohol PDFMartis JonasBelum ada peringkat

- Bipolar DisorderDokumen20 halamanBipolar Disorderabk52166Belum ada peringkat

- Ltz-Psychodiagnostics Intro-Evolution, Growth and DevelopmentDokumen88 halamanLtz-Psychodiagnostics Intro-Evolution, Growth and DevelopmentLucy RalteBelum ada peringkat

- Fernando - Waters2014Dokumen13 halamanFernando - Waters2014fernandogfcnsBelum ada peringkat

- Psychogenic DystoniaDokumen2 halamanPsychogenic DystoniaTomiuc AndreiBelum ada peringkat

- Neurosyphilis Presenting As Psychiatric Symptoms - An Unusual Case ReportDokumen3 halamanNeurosyphilis Presenting As Psychiatric Symptoms - An Unusual Case ReportKinga KlimczykBelum ada peringkat

- Related LiteratureDokumen16 halamanRelated LiteratureivahcamilleBelum ada peringkat

- Psychosurgery, Epilepsy Surgery, or Surgical Psychiatry: The Tangled Web of Epilepsy and Psychiatry As Revealed by Surgical OutcomesDokumen2 halamanPsychosurgery, Epilepsy Surgery, or Surgical Psychiatry: The Tangled Web of Epilepsy and Psychiatry As Revealed by Surgical Outcomesximena sanchezBelum ada peringkat

- Biomarcadores Neuroinmunes en Esquizofrenia. 2014Dokumen11 halamanBiomarcadores Neuroinmunes en Esquizofrenia. 2014Stephanie LandaBelum ada peringkat

- Pappolla Familial Hypercholesterolemia and Mild Cognitive ImpairmentDokumen13 halamanPappolla Familial Hypercholesterolemia and Mild Cognitive ImpairmentMike Pappolla MD, PhDBelum ada peringkat

- Schizophrenia: Overview and Treatment OptionsDokumen18 halamanSchizophrenia: Overview and Treatment OptionsMeindayaniBelum ada peringkat

- CH 4Dokumen11 halamanCH 4Usman khalidBelum ada peringkat

- Popovic Et Al-2014-Acta Psychiatrica ScandinavicaDokumen9 halamanPopovic Et Al-2014-Acta Psychiatrica ScandinavicaCarolina MuñozBelum ada peringkat

- Schizophrenia UndifferentiatedDokumen64 halamanSchizophrenia UndifferentiatedJen GarzoBelum ada peringkat

- Schizophrenia:Courseoverthe Lifetime: Philipd - Harvey MichaeldavidsonDokumen16 halamanSchizophrenia:Courseoverthe Lifetime: Philipd - Harvey MichaeldavidsonGeorgiana BlagociBelum ada peringkat

- Atypical antipsychotics for schizophrenia and substance abuseDokumen14 halamanAtypical antipsychotics for schizophrenia and substance abusecupin 69PKBelum ada peringkat

- 52 Tripathy EtalDokumen5 halaman52 Tripathy EtaleditorijmrhsBelum ada peringkat

- Course of OCDDokumen16 halamanCourse of OCDShwetank BansalBelum ada peringkat

- Psychosis and Seizure Disorder: Challenges in Diagnosis and TreatmentDokumen7 halamanPsychosis and Seizure Disorder: Challenges in Diagnosis and TreatmentgreenanubisBelum ada peringkat

- Jamapsychiatry 2019 3360Dokumen10 halamanJamapsychiatry 2019 3360Furqan BansirBelum ada peringkat

- Neurobiology of SchizophreniaDokumen11 halamanNeurobiology of SchizophreniaJerry JacobBelum ada peringkat

- Handbook of Medical Neuropsychology: Applications of Cognitive NeuroscienceDari EverandHandbook of Medical Neuropsychology: Applications of Cognitive NeuroscienceBelum ada peringkat

- Psychoanalysis (Barnes & Noble Digital Library): Its Theories and Practical Application, Third EditionDari EverandPsychoanalysis (Barnes & Noble Digital Library): Its Theories and Practical Application, Third EditionBelum ada peringkat

- Keys CardiologyDokumen1 halamanKeys CardiologyDrashua AshuaBelum ada peringkat

- DM CardiologyDokumen39 halamanDM CardiologyDrashua AshuaBelum ada peringkat

- Bence Jones Protein-UrineDokumen16 halamanBence Jones Protein-UrineDrashua Ashua100% (2)

- Post Graduate Medical Admission Test (Pgmat) - 2014 For MD/MS/PGD, MDS & MD (Ayurveda)Dokumen1 halamanPost Graduate Medical Admission Test (Pgmat) - 2014 For MD/MS/PGD, MDS & MD (Ayurveda)Drashua AshuaBelum ada peringkat

- ABO in The Context ofDokumen21 halamanABO in The Context ofDrashua AshuaBelum ada peringkat

- Compliance rate study of bio-medical waste segregationDokumen50 halamanCompliance rate study of bio-medical waste segregationAman Dheer Kapoor100% (2)

- Bihar PG15 ProspectusDokumen37 halamanBihar PG15 ProspectusDrashua AshuaBelum ada peringkat

- Breast Cancer Grading PDFDokumen1 halamanBreast Cancer Grading PDFDrashua AshuaBelum ada peringkat

- Post Graduate Medical Admission Test (Pgmat) - 2015 For MD/MS/PGD, MDS & MD (Ayurveda)Dokumen2 halamanPost Graduate Medical Admission Test (Pgmat) - 2015 For MD/MS/PGD, MDS & MD (Ayurveda)Drashua AshuaBelum ada peringkat

- Post Graduate Medical Admission Test (Pgmat) - 2015 For MD/MS/PGD, MDS & MD (Ayurveda)Dokumen2 halamanPost Graduate Medical Admission Test (Pgmat) - 2015 For MD/MS/PGD, MDS & MD (Ayurveda)Drashua AshuaBelum ada peringkat

- Muscle Origins and InsertionsDokumen9 halamanMuscle Origins and Insertionsnoisytaost92% (12)

- HematologyDokumen58 halamanHematologyAchmad DainuriBelum ada peringkat

- Telephone Directory EngDokumen8 halamanTelephone Directory EngDrashua AshuaBelum ada peringkat

- CBD FullDokumen5 halamanCBD FullDrashua AshuaBelum ada peringkat

- Bio Medical Rules PDFDokumen28 halamanBio Medical Rules PDFDrashua AshuaBelum ada peringkat

- Hilgendorf Bio 07Dokumen52 halamanHilgendorf Bio 07Drashua AshuaBelum ada peringkat

- Shigella BackgroundDokumen2 halamanShigella BackgroundDrashua AshuaBelum ada peringkat

- Application PDFDokumen2 halamanApplication PDFDrashua AshuaBelum ada peringkat

- SHIGELLOSISDokumen1 halamanSHIGELLOSISDrashua AshuaBelum ada peringkat

- P 133-1430Dokumen11 halamanP 133-1430Drashua AshuaBelum ada peringkat

- ID 20i2.1Dokumen12 halamanID 20i2.1Drashua AshuaBelum ada peringkat

- Ecp Shigella InfectionDokumen4 halamanEcp Shigella InfectionDrashua AshuaBelum ada peringkat

- P 133-1430Dokumen11 halamanP 133-1430Drashua AshuaBelum ada peringkat

- Shigella in Child-Care SettingsDokumen2 halamanShigella in Child-Care SettingsDrashua AshuaBelum ada peringkat

- ShigellaDokumen1 halamanShigellaDrashua AshuaBelum ada peringkat

- Shige LLDokumen7 halamanShige LLDrashua AshuaBelum ada peringkat

- 420 079 Guideline ShigellosisDokumen7 halaman420 079 Guideline ShigellosisDrashua AshuaBelum ada peringkat

- Shigellosis: Frequently Asked QuestionsDokumen2 halamanShigellosis: Frequently Asked QuestionsDrashua AshuaBelum ada peringkat

- ShigellaDokumen2 halamanShigellaDrashua AshuaBelum ada peringkat

- 0314Dokumen6 halaman0314Drashua AshuaBelum ada peringkat

- dlp4 Math7q3Dokumen3 halamandlp4 Math7q3Therence UbasBelum ada peringkat

- MT 1 Combined Top 200Dokumen3 halamanMT 1 Combined Top 200ShohanBelum ada peringkat

- Garner Fructis ShampooDokumen3 halamanGarner Fructis Shampooyogesh0794Belum ada peringkat

- Unit 5 The Teacher As ProfessionalDokumen23 halamanUnit 5 The Teacher As ProfessionalLeame Hoyumpa Mazo100% (5)

- Sample Detailed EvaluationDokumen5 halamanSample Detailed Evaluationits4krishna3776Belum ada peringkat

- English FinalDokumen321 halamanEnglish FinalManuel Campos GuimeraBelum ada peringkat

- Mexican Immigrants and The Future of The American Labour Market (Schlossplatz3-Issue 8)Dokumen1 halamanMexican Immigrants and The Future of The American Labour Market (Schlossplatz3-Issue 8)Carlos J. GuizarBelum ada peringkat

- Here Late?", She Asked Me.: TrangDokumen3 halamanHere Late?", She Asked Me.: TrangNguyễn Đình TrọngBelum ada peringkat

- Alluring 60 Dome MosqueDokumen6 halamanAlluring 60 Dome Mosqueself sayidBelum ada peringkat

- Comparing and contrasting inductive learning and concept attainment strategiesDokumen3 halamanComparing and contrasting inductive learning and concept attainment strategiesKeira DesameroBelum ada peringkat

- Dead Can Dance - How Fortunate The Man With None LyricsDokumen3 halamanDead Can Dance - How Fortunate The Man With None LyricstheourgikonBelum ada peringkat

- Adult Education and Training in Europe 2020 21Dokumen224 halamanAdult Education and Training in Europe 2020 21Măndița BaiasBelum ada peringkat

- Infinitive Clauses PDFDokumen3 halamanInfinitive Clauses PDFKatia LeliakhBelum ada peringkat

- AL E C Usda S W P: OOK AT THE Ngineering Hallenges OF THE Mall Atershed RogramDokumen6 halamanAL E C Usda S W P: OOK AT THE Ngineering Hallenges OF THE Mall Atershed RogramFranciscoBelum ada peringkat

- History: The Origin of Kho-KhotheDokumen17 halamanHistory: The Origin of Kho-KhotheIndrani BhattacharyaBelum ada peringkat

- Research 2020.21 Outline PDFDokumen12 halamanResearch 2020.21 Outline PDFCharles MaherBelum ada peringkat

- Corporate Office Design GuideDokumen23 halamanCorporate Office Design GuideAshfaque SalzBelum ada peringkat

- Piramal Annual ReportDokumen390 halamanPiramal Annual ReportTotmolBelum ada peringkat

- Effective Instruction OverviewDokumen5 halamanEffective Instruction Overviewgene mapaBelum ada peringkat

- FOREIGN DOLL CORP May 2023 TD StatementDokumen4 halamanFOREIGN DOLL CORP May 2023 TD Statementlesly malebrancheBelum ada peringkat

- Álvaro García Linera A Marxist Seduced BookDokumen47 halamanÁlvaro García Linera A Marxist Seduced BookTomás TorresBelum ada peringkat

- Financial Management Module - 3Dokumen2 halamanFinancial Management Module - 3Roel AsduloBelum ada peringkat

- 3 QDokumen2 halaman3 QJerahmeel CuevasBelum ada peringkat

- Alsa Alsatom MB, MC - Service ManualDokumen26 halamanAlsa Alsatom MB, MC - Service ManualJoão Francisco MontanhaniBelum ada peringkat

- Lab Report FormatDokumen2 halamanLab Report Formatapi-276658659Belum ada peringkat

- JDDokumen19 halamanJDJuan Carlo CastanedaBelum ada peringkat

- MEAB Enewsletter 14 IssueDokumen5 halamanMEAB Enewsletter 14 Issuekristine8018Belum ada peringkat

- iPhone Repair FormDokumen1 halamaniPhone Repair Formkabainc0% (1)

- Block 2 MVA 026Dokumen48 halamanBlock 2 MVA 026abhilash govind mishraBelum ada peringkat

- The Wavy Tunnel: Trade Management Jody SamuelsDokumen40 halamanThe Wavy Tunnel: Trade Management Jody SamuelsPeter Nguyen100% (1)